Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate whether there are associations between exposure to pesticides and 4 chronic non-cancer health effects: dermatologic, neurologic, reproductive, and genotoxic effects.

DATA SOURCES

We searched PreMedline, MEDLINE, and LILACS using the key word pesticide combined with the term for the specific health effect being searched. Reviewers scanned the references of all articles for additional relevant studies.

STUDY SELECTION

Studies since 1992 were assessed using structured inclusion and quality-of-methods criteria. Studies scoring <4 on a 7-point global methodologic quality scale were excluded. In total, 124 studies were included. These studies had a mean quality score of 4.88 out of 7.

SYNTHESIS

Strong evidence of association with pesticide exposure was found for all neurologic outcomes, genotoxicity, and 4 of 6 reproductive effects: birth defects, fetal death, altered growth, and other outcomes. Exposure to pesticides generally doubled the level of genetic damage as measured by chromosome aberrations in lymphocytes. Only a few high-quality studies focused on the dermatologic effects of pesticides. In some of these studies, rates of dermatitis were higher among those who had had high exposure to pesticides on the job.

CONCLUSION

Evidence from research on humans consistently points to positive associations between pesticide exposure and 3 of the 4 non-cancer health outcomes studied. Physicians have a dual role in educating individual patients about the risks of exposure and in reducing exposure in the community by advocating for restrictions on use of pesticides.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Déterminer s’il existe une association entre l’exposition à des pesticides et 4 types d’effets nocifs chroniques sur la santé, outre le cancer: effets d’ordre dermatologique, neurologique, reproducteur et génotoxique.

SOURCES DES DONNÉES

On a consulté PreMedline, MEDLINE et LILACS à l’aide du mot-clé pesticide combiné à chacun des termes désignant les effets spécifiques à l’étude. Les analystes ont scruté la bibliographie de chaque article pour identifier toute autre étude pertinente.

CHOIX DES ÉTUDES

Le choix des études publiées depuis 1992 était basé sur des critères d’inclusion structurés et des critères de qualité méthodologique. Les études obtenant un score inférieur à 4 sur une échelle de qualité méthodologique globale de 7 points ont été exclues. Au total, 124 études ont été retenues, avec un score de qualité moyen de 4,88 sur 7.

SYNTHÈSE

On a trouvé des preuves convaincantes d’une association entre l’exposition aux pesticides et l’ensemble des issues neurologiques, la génotoxicité et 4 des 6 effets sur la reproduction: malformations congénitales, mort fœtale, anomalie de croissance et autres issues. De façon générale, l’exposition aux pesticides a doublé le niveau de dommage génétique tel que mesuré par les modifications chromosomiques dans les lymphocytes. Seules quelques études de bonne qualité ont porté sur les effets dermatologiques des pesticides. Dans certaines de ces études, on a observé un taux plus élevé de dermatites chez ceux qui avaient été fortement exposés en milieu de travail.

CONCLUSION

La plupart des données tirées de la recherche chez l’humain indiquent que l’exposition à des pesticides est associée à 3 des 4 problèmes de santé étudiés. Le médecin a le double rôle de renseigner chaque patient sur les risques d’une telle exposition et de promouvoirun usage restreint des pesticides afin de réduire l’exposition dans la communauté.

Pesticides include all classes of chemicals used to kill or repel insects, fungi, vegetation, and rodents.1,2 It is well accepted that acute poisonings cause health effects, such as seizures, rashes, and gastrointestinal illness.1–4 Chronic effects, such as cancer and adverse reproductive outcomes, have also been studied extensively, and the results have been interpreted in various ways as evidence that pesticides aresafe or area cause for concern because they can be detrimental to human health. Bylaw debates across Canada have focused public attention on the cosmetic (non-commercial crop) uses of pesticides and the attendant potential risks of chronic low-level exposure.

Family physicians need evidence-based information on the health effects of pesticides to guide their advice to patients and their involvement in community decisions to restrict use of pesticides. A systematic review by the Ontario College of Family Physicians’ Environmental Health Committee was done as a basis for informing family physicians’ approach to disseminating information on pesticides to patients and communities.5

This article reports on a systematic review of articles published between 1992 and 2003 on 4 non-cancer chronic health effects thought to be associated with exposure to pesticides: dermatologic, neurologic, reproductive, and genotoxic effects. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and learning disability outcomes were not included in the review because of resource constraints. Findings on pesticides and cancer outcomes are reported in another article.6

DATA SOURCES

Primary peer-reviewed studies were located using PreMedline, MEDLINE, and LILACS (Spanish- and Portuguese-language articles) databases. All searches included the key MeSH heading “pesticides” combined with the MeSH heading for the health effects under study. Reviewers systematically scanned the references of all articles for additional relevant studies.

Study selection

The 3 criteria for inclusion in the assessment were being peer reviewed, being a study of human health effects related to pesticide exposure, and being published between 1992 and 2003. A systematic review done in 1993 had covered pesticide health effect studies up to 1991.7 A total of 150 studies were retrieved by the search for the 4 categories of health effects (Table 1). Two independent reviewers each filled out 5-page Data Extraction Forms for each study. A 7-point Likert-type Global Methodological Quality Assessment Scale was used to assess all papers; 26 papers scored <4 out of 7 and were excluded.

Table 1.

Summary of studies reviewed

| HEALTH EFFECT | NO. OF STUDIES FOUND | NO. OF STUDIES INCLUDED* | SUMMARY OF RESULTS | MEAN GLOBAL SCORE OF STUDIES INCLUDED* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatologic effects | 11 | 10 | 7/10 studies positive for dermatitis with pesticide exposure | 4.50 |

| Neurotoxicity | 60 | 41 | 39/41 studies positive for increase in1 or more neurologic abnormalities with pesticide exposure | 4.99 |

| Reproductive outcomes | 64 | 59 | Birth defects: 14/15 studies positive; time to pregnancy: 5/8 studies positive; fertility: 7/14 studies positive; altered growth: 7/10 studies positive; fetal death: 9/11 studies positive; other outcomes: 6/6 studies positive | 4.83 |

| Genotoxicity | 15 | 14 | 11/14 studies positive for increased chromosome aberrations with pesticide exposure† | 5.03 |

Assessors scored each paper on a 7-point scale for methodologic quality from 1—very poor to 7—excellent. Papers scoring <4 were excluded.

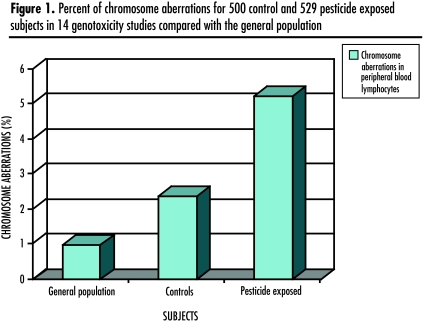

Figure 1 aggregates results from all 14 genotoxicity studies.

SYNTHESIS

Dermatologic effects

Skin is the primary route of exposure to pesticides for sprayers, handlers, and people using repellants. Excluding acute poisonings, contact dermatitis is thought to be the most common health effect of pesticides, through either irritant or allergic mechanisms.8 Along with eye injuries, it is the health effect most likely to be seen in the office2 and might be the only indicator of exposure.

In the 10 studies reviewed9–18 (none from Canada), it was difficult to assess the prevalence of skin disorders attributable to pesticides. In agricultural workers with contact dermatitis, sensitization to both plant material and pesticides was documented,9,16 but most study designs did not allow attribution of rashes specifically to pesticide exposure. One study that used a biomarker for pesticide exposure found a dose-response relationship between dermatitis and years of fungicide exposure or poor application practices13; 61% of pesticide-exposed agricultural workers and 31% of controls had dermatitis (P < .001).13 Pet groomers who gave more than 75 pyrethrin flea treatments per year had more rashes (odds ratio [OR] 2.04, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02 to 4.09) and more eye symptoms (OR 4.75, 95% CI 1.14 to 18.23) than those who gave fewer treatments.10

Neurotoxicity

Long-term effects of pesticides on the nervous system include cognitive and psychomotor dysfunction, and neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental effects. Pesticide poisonings result in well-described acute and chronic neurotoxic syndromes.19 Chronic effects from low or moderate exposures have been less well documented.

Our systematic review began with 4 relevant studies, including a metanalysis on Parkinson disease (PD) and pesticide exposure20; 41 primary studies21–62 were of adequate quality. Most studies analyzed covariates that might affect nervous system function. Differentiating between the effects of chronic or cumulative exposure and current intense exposure can be difficult. Unfortunately for many exposed populations (eg, Ecuadorian farm families29,30), mixed past poisoning, cumulative exposure, and current work and home exposures are overlaid.

Maternal, in-utero, and early childhood exposures are likely all involved in producing neurodevelopmental effects in preschool children in pervasive exposure situations, such as Mexican valley agriculture.40 Only 2 studies of effects including children were found,40,42 despite considerable concern about the effects of pesticide exposure on sensitive populations, such as inner-city children.4

Most studies documented mixed pesticide exposures. Cross-sectional studies often included exposure biomarkers, such as herbicide or alkyl phosphates in urine or acetylcholinesterase levels in blood. Some studies were exceptional in documenting specific exposures, for example, fumigants.28

General neurotoxic morbidity. General malaise and mild cognitive dysfunction might be the earliest neurotoxic responses to pesticide exposure.62 Most studies using validated questionnaires and performance tests found an increased prevalence of symptoms or mood changes, as well as alterations in neurobehavioural performance and cognitive function.

Studies of the mental and emotional effects of pesticides found associations for current minor psychiatric morbidity,27 depression,55 suicide among Canadian farmers,49 and death from mental disorders,60 particularly neurotic disorders in women. Keifer et al42 found substantially higher rates of mental and emotional symptoms in residents (including adolescents) exposed to spray-plane drift compared with those not exposed.

Associations between previous pesticide poisonings, particularly from organophosphates and carbamates, and decreases in current neurobehavioural function were most consistently positive. Those with greater exposures (eg, termiticide applicators31 or farmers handling concentrates50) also showed more consistent decreases in function. Together, these studies provide important evidence of the subclinical effects of pesticides on the nervous system. These effects might become clinically manifest in a few cases.

Neurodegenerative disease

Most of these studies examined mixed occupational exposures. Some focused on herbicides. Health outcomes varied from PD on clinical examination through adjusted incidence of hospitalization for PD to deaths from PD. All found positive associations between exposure and PD. Combined with the earlier meta-analysis,20 the results of 15 out of 26 studies were positive for associations between pesticide exposure and PD. These data provide remarkably consistent evidence of a relationship between PD and past exposure to pesticides on the job (OR 1.8 to 2.5).

Evidence of other neurodegenerative effects of pesticides is also accumulating. Of 2 studies on Alzheimer disease, 138 found no association and 124 found an association in men. A study on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis46 found consistently elevated adjusted ORs associated with pesticide exposure in both men and women.

Reproductive outcomes

Six distinct groups of reproductive outcomes were chosen for study: birth defects, fecundability, fertility, altered growth, fetal death, and mixed outcomes.

Birth defects

Fifteen studies from 9 countries63–77 examined associations between pesticides and birth defects. The studies consistently showed increased risk with pesticide exposure. Specific defects included limb reductions,64,67,73 urogenital anomalies,68,73,75 central nervous system defects,68,73 orofacial clefts,74 heart defects,66,67 and eye anomalies.77 The rate of any birth defect was also increased by parental exposure to pesticides.66–71,74,76 In many studies, there were multiple exposures. Two studies identified specific pesticides: glyphosate64 and the pyridil derivatives.69

Time to pregnancy

Eight studies from 6 countries78–85 analyzed associations between pesticide exposure and time to pregnancy. Data on pesticide exposures and outcome were collected retrospectively by self-report. Five studies showed positive associations, and 3 showed no association between pesticide exposure and time to pregnancy. All 3 papers showing no association collected exposure and outcome information from men only.79–81

Fertility

Fertility refers to the ability to become pregnant in 1 year and includes male and female factors, such as semen quality and infertility. Twelve studies from 7 countries were reviewed.86–99 Results were mixed; several studies found no associations between pesticide exposure and sperm abnormalities. One study found an association between organophosphate metabolites and sperm sex aneuploidies94; another study found an association between erectile dysfunction and pesticide exposure.95 One study found an increased risk of infertility among women who worked with herbicides in the 2 years before attempted conception.98

Altered growth

Low birth weight, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction are not only important determinants of health during the first year of life, but also of chronic diseases of adulthood.100 Ten studies, mainly from Europe and North America,76,77,101–108 examined pesticide effects on fetal growth. Seven of these showed positive associations between agricultural pesticide exposure and altered fetal growth. Two pesticides implicated in the positive studies were pyrethroids and chlorpyrifos, the latter a commonly used ant-killer now being phased out because of health effects.

Fetal death

Fetal death includes spontaneous abortion, fetal death, stillbirth, and neonatal death. Results were consistent across several study designs; 9 of 11 studies64,76,77,109–116 found positive associations with pesticide exposure. The Ontario Farm Study results suggested critical windows when pesticide exposure is most harmful. Preconception exposure was associated with early first-trimester abortions, and post-conception exposure was associated with late spontaneous abortions.110 In a study from the Philippines,76 risk of spontaneous abortion was 6 times higher in farming households with heavy pesticide use than it was among those using integrated pest management (which results in reduced pesticide use).

Other reproductive outcomes

Seven studies examined other reproductive outcomes, such as sex ratio, placental quality, and developmental delay after in-utero exposure.64,107,117–121 A Mexican study115 found higher rates of placental infarction in rural women exposed to organophosphate insecticides; exposure was biomarker-documented with depressed red blood cell cholinesterase levels. Results on altered sex ratios were inconsistent.64,114

Genotoxicity

Genotoxicity is the ability of a pesticide to cause intracellular genetic damage. In all reported studies, it was measured as percent chromosome aberrations per 100 peripheral blood lymphocytes. Increased frequency of chromosome aberrations was a predictor of increased cancer rates in a large prospective cohort study (n = 5271) with follow-up for 13 to 23 years.122 Similar studies of associations with reproductive outcomes have not been done.

Important confounders are exposures that cause genetic damage: smoking, alcohol consumption, diet, caffeine intake, radiation, and mutagenic drugs. The latter are important since drugs such as methotrexate are now used widely for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn disease. Few studies measured all confounders; most excluded smokers and subjects who had x-rays or took mutagenic drugs during the previous year.

Positive associations between pesticide exposure and elevated percent chromosome aberrations were found in 11 of 14 studies.123–136 Two studies showing no association had taken blood samples during low-exposure seasons.128,129 Two studies pointed to synthetic pyrethrins134 and organophosphates135 as highly genotoxic. Aggregate results from all 14 studies are shown in Figure 1; pesticide exposure doubled the frequency of chromosome aberrations. In clinical practice, these aberrations could present as spontaneous abortion, birth defects, sperm abnormalities, or cancer risk.

Figure 1.

Percent of chromosome aberrations for 500 control and 529 pesticide exposed subjects in 14 genotoxicity studies compared with the general population

DISCUSSION

For the 4 non-cancer effects reviewed, the strongest evidence of association with pesticide exposure was found for neurologic abnomalities, 4 out of 6 reproductive outcomes, and genotoxicity effects (Table 1).

The most striking feature of the results of this systematic review is the consistency of evidence showing that pesticide exposure increases the risk of 3 non-cancer health effects: neurologic, reproductive, and genotoxic effects. The results are consistent with those of other reviews published before20 and since137,138 this review was completed. Results of dermatologic studies are less consistent and of poorer quality and indicate the need for a primary care prevalence study of pesticide-related skin conditions.

Assessment of exposure remains a key problem that is being addressed in newer studies by enhanced biomonitoring. For example, a cohort of children now being followed longitudinally had cord-blood levels of several pesticides measured at birth139 and by maternal air and blood sampling during pregnancy.140 The role of genetics in the ability to metabolize pesticides, which varies widely among ethnic groups,141 is being incorporated into more study designs41,124,142 and should refine our knowledge and explain some inconsistencies in the international literature.

Limitations

The major limitation of studies of the health effects of pesticides is their inability to demonstrate cause-effect relationships. Study subjects cannot be deliberately exposed to potentially harmful toxins, and few exposure-reduction options are tested in randomized controlled trials. The evidence generated by well-constructed clinical and epidemiologic observational studies is the highest level of evidence we can ethically obtain.

The studies reviewed have methodologic problems, such as exposure misclassification and inadequate exposure assessment (causing mixed results) and recall bias (in retrospective case-control studies). Unpublished literature on health effects that was not accessed would be useful to determine whether there is a publication bias toward positive studies. The effect of unpublished positive or negative studies generated by chemical industry–funded research also cannot be assessed. Many good-quality studies were found in the review, however, and taken together, the results provide sufficient cause for family doctors to educate patients and to act to prevent unnecessary pesticide exposure.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review provides clear evidence that pesticide exposure increases risk to human health across a range of exposure situations and vulnerable populations. Public support for restrictions on pesticide use is growing; 71% of respondents supported provincewide restrictions in a recent Ontario poll.143 The Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment144 and national pediatric and public health groups in Canada and the United States145–8 have expressed concern about health effects from cosmetic use of pesticides and recommended that physicians participate in reduction efforts.

Family doctors have a dual role in reducing pesticide exposures. First, during individual encounters, we can educate patients about pesticide health effects,149 monitor through exposure histories150 and laboratory tests,151 and advise when we believe the level of exposure poses a health threat. We should encourage harm reduction through use of protective equipment when pesticide exposure is necessary. Advice about use of protective equipment is an important and neglected area of family practice,152 although it is an effective intervention for reducing pesticide exposure.133,153 Then, in our role as public and community health advocates, we need to educate the public about the health effects of pesticide use. We need to reinforce community efforts to reduce cosmetic use of pesticides that can disproportionally affect children, pregnant women, and elderly people.

Practice tips based on the review

-

Advise patients to avoid pesticide exposure during critical reproductive periods. This includes occupational, indoor, lawn, and garden exposure to pesticides.

For women, the critical period for early spontaneous abortion is before pregnancy, and for late spontaneous abortion, the first trimester.

For men, the critical period is the 3 months of spermatogenesis before conception.

-

Take a pesticide-exposure history from patients who have adverse reproductive events, such as intrauterine growth restriction, prematurity, inability to conceive in 1 year, or birth defects.

Birth defects are associated with both maternal and paternal exposure to pesticides before conception and during the first trimester.

Most exposures are work related, but transposition of the great vessels is increased with household exposure.

-

Screen patients with a history of exposure to pesticides for neurologic conditions (which can be subtle).

Occupationally exposed adults are at increased risk of neurologic symptoms, including neurobehavioural changes and Parkinson disease.

Use biomonitoring as an effective tool to reduce exposure. Biomonitoring for recent (within 3 months) organophosphate insecticide exposure is done by ordering red blood cell cholinesterase tests.2 The test is covered by the Ontario Health Insurance Plan; in other provinces, it costs $25 to $100, but might be covered for exposed workers.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Due to the unethical nature of cause-effect studies on pesticide exposure, the growing body of literature on pesticide health effects cannot be used to establish a cause-effect relationship between the use of pesticides and non-cancer health effects.

However, there is consistent evidence in the literature that pesticide exposure does increase the risk of 3 non-cancer health effects (neurologic, reproductive, and genotoxic).

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

En raison de la nature non éthique des études de type cause-effets sur l’exposition aux pesticides, on ne peut utiliser les données de plus en plus nombreuses de la littérature dans ce domaine pour éta-blir une relation de cause à effet entre l’utilisation des pesticides et les effets sur la santé autres que les cancers.

Il existe toutefois dans la littérature des preuves abondantes confirmant que l’exposition aux pesticides augmente le risque de développer trois effets nocifs autres que cancéreux: effets sur le système nerveux, sur la reproduction et génotoxicité.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The systematic review was completed with funding from the Laidlaw Foundation and the Ontario College of Family Physicians. Dr Sanborn, Dr Kerr, and Dr Vakil received honoraria from the Ontario College of Family Physicians for working on this article. Dr Cole has received funding from the International Development Research Centre and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research around pesticides but not for this review. Although Ms Bassil currently works in the Environmental Protection Office at Toronto Public Health in Ontario, she was not employed there while working on the systematic review. Dr Vakil has received teaching honoraria from the Ontario College of Family Physicians and the International Joint Commission Health Professional Task Force.

Contributors

Dr Sanborn, Dr Kerr, Dr Sanin, Dr Cole, Ms Bassil, and Dr Vakil contributed to concept and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation, and preparing the article for submission.

References

- 1.Guidotti TL, Gosselin P, editors. The Canadian guide to health and the environment. Edmonton, Alta: University of Alberta Press and Duval House Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reigert JR, Roberts JR. Recognition and management of pesticide poisonings. 5. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 1999. [Accessed 2007 September 12]. Available from: www.epa.gov/pesticides/safety/healthcare/handbook/handbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alarcon WA, Calvert GM, Blondell JM, Mehler LN, Sievert J, Propeck M, et al. Acute illnesses associated with pesticide exposure at schools. JAMA. 2005;294(4):455–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landrigan PJ, Claudio L, Markowitz SB, Brenner BL, Romero H, Wetmur JG, et al. Pesticides and inner-city children: exposures, risks and prevention. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(Suppl 3):431–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanborn M, Cole D, Kerr K, Vakil C, Sanin LH, Bassil K. Pesticides literature review. Toronto, Ont: Ontario College of Family Physicians; 2004. [Accessed 2007 August 29]. Available from: www.ocfp.on.ca/local/files/Communications/Current%20Issues/Pesticides/Final%20Paper%2023APR2004.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassil KL, Vakil C, Sanborn MD, Cole DC, Kaur JS, Kerr KJ. Cancer health effects of pesticides: a systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1704–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maroni M, Fait A. Health effects in man from long-term exposure to pesticides. A review of the 1975–1991 literature. Toxicology. 1993;78(1–3):1–180. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90227-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiewak R. Pesticides as a cause of occupational skin diseases in farmers. Ann Agricultur Environ Med. 2000;8:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruynzeel DP, de Boer EM, Brouwer EJ, de Wolff FA, de Haan P. Dermatitis in bulb growers. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:11–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1993.tb04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukowski J, Brown C, Korn LR, Meyer LW. Prevalence of and potential risk factors for symptoms associated with insecticide use among animal groomers. J Occup Environ Med. 1996;38:528–34. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199605000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro-Gutierrez N, McConnell R, Andersson K, Pacheco-Anton F, Hogstedt C. Respiratory symptoms, spirometry and chronic occupational paraquat exposure. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23:421–7. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cellini A, Offidani A. An epidemiological study on cutaneous diseases of agricultural workers authorized to use pesticides. Dermatology. 1994;189:129–32. doi: 10.1159/000246815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole DC, Carpio F, Math JJ, Leon N. Dermatitis in Ecuadorian farm workers. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1997.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper SP, Downs T, Burau K, Buffler PA, Tucker S, Whitehead L, et al. A survey of actinic keratoses among paraquat production workers and a non-exposed friend reference group. Am J Ind Med. 1994;25:335–47. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700250304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo YL, Wang BJ, Lee CC, Wang JD. Prevalence of dermatoses and skin sensitization associated with use of pesticides in fruit farmers of southern Taiwan. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53:427–31. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.6.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paulsen E. Occupational dermatitis in Danish gardeners and greenhouse workers (II). Etiological factors. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38:14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penagos HG. Contact dermatitis caused by pesticides among banana plantation workers in Panama. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:14–8. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2002.8.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rademaker M. Occupational contact dermatitis among New Zealand farmers. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:164–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage EP, Keefe TJ, Mounce LM, Heaton RK, Lewis JA, Burcar BJ. Chronic neurological sequelae of acute organophosphate pesticide poisoning. Arch Environ Health. 1988;43:38–45. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.9934372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Priyadarshi A, Khuder SA, Schaub EA, Shrivastava S. A meta-analysis of Parkinson’s diseaseand exposure topesticides. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21(4):435–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amado F, Carvallo B, Silva JI, Londono JL, Restrepo H. Prevalencia de discromatopsia adquirida y exposicion a plaguicidas y a radiacion ultravioleta solar. Rev Fac Nac Salud Publica. 1997;15(1):69–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ames RG, Steenland K, Jenkins B, Chrislip D, Russo J. Chronic neurologic sequelae to cholinesterase inhibition among agricultural pesticide applicators. Arch Environ Health. 1995;50:440–4. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1995.9935980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldi I, Filleul L, Mohammed-Brahim B, Fabrigoule C, Dartigues JF, Schwall S, et al. Neuropsychologic effects of long-term exposure to pesticides: results from the French Phytoner study. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:839–44. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldi I, Lebailly P, Mohammed-Brahim B, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF, Brochard P. Neurodegenerative diseases and exposure to pesticides in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:409–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bazylewicz-Walczak B, Majczakowa W, Szymczak M. Behavioral effects of occupational exposure to organophosphorous pesticides in female greenhouse planting workers. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:819–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beach JR, Spurgeon A, Stephens R, Heafield T, Calvert IA, Levy LS, et al. Abnormalities on neurological examination among sheep farmers exposed to organophosphorous pesticides. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53:520–5. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.8.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowler RM, Mergler D, Huel G, Cone JE. Psychological, psychosocial, and psychophysiological sequelae in a community affected by a railroad chemical disaster. J Traum Stress. 1994;7:601–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02103010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvert GM, Mueller CA, Fajen JM, Chrislip DW, Russo J, Briggle T, et al. Health effects associated with sulfuryl fluoride and methyl bromide exposure among structural fumigation workers. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1774–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.12.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole DC, Carpio F, Julian J, Leon N. Assessment of peripheral nerve function in an Ecuadorian rural population exposed to pesticides. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1998;55:77–91. doi: 10.1080/009841098158520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole DC, Carpio F, Julian J, Leon N, Carbotte R, De Almeida H. Neurobehavioral outcomes among farm and nonfarm rural Ecuadorians. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1997;19:277–86. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dick RB, Steenland K, Krieg EF, Hines CJ. Evaluation of acute sensory-motor effects and test sensitivity using termiticide workers exposed to chlorpyrifos. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:381–93. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engel LS, Keifer MC, Checkoway H, Robinson LR, Vaughan TL. Neurophysiological function in farm workers exposed to organophosphate pesticides. Arch Environ Health. 1998;53:7–14. doi: 10.1080/00039899809605684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engel LS, Checkoway H, Keifer MC, Seixas NS, Longstreth WT, Jr, Scott KC, et al. Parkinsonism and occupational exposure to pesticides. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:582–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.9.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ernest K, Thomas M, Paulose M, Rupa V, Gnanamuthu C. Delayed effects of exposure to organophosphorus compounds. Ind J Med Res. 1995;101:81–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farahat TM, Abdelrasoul GM, Amr MM, Shebl MM, Farahat FM, Anger WK. Neurobehavioural effects among workers occupationally exposed to organophosphorous pesticides. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:279–86. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faria NM, Facchini LA, Fassa AG, Tomasi E. [A cross-sectional study about mental health of farm-workers from Serra Gaucha (Brazil)] Revista de Saude Publica. 1999;33:391–400. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101999000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiedler N, Kipen H, Kelly-McNeil K, Fenske R. Long-term use of organophosphates and neuropsychological performance. Am J Ind Med. 1997;32:487–96. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199711)32:5<487::aid-ajim8>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gauthier E, Fortier I, Courchesne F, Pepin P, Mortimer J, Gauvreau D. Environmental pesticide exposure as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control study. Environ Res. 2001;86:37–45. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Richardson RJ. The risk of Parkinson’s disease with exposure to pesticides, farming, well water, and rural living. Neurology. 1998;50:1346–50. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillette EA, Meza MM, Aquilar MG, Soto AD, Garcia IE. An anthropological approach to the evaluation of preschool children exposed to pesticides in Mexico. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(6):347–53. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubble JP, Kurth JH, Glatt SL, Kurth MC, Schellenberg GD, Hassanein RE, et al. Gene-toxin interaction as a putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Neuroepidemiology. 1998;17:96–104. doi: 10.1159/000026159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keifer M, Rivas F, Moon JD, Checkoway H. Symptoms and cholinesterase activity among rural residents living near cotton fields in Nicaragua. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53:726–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.53.11.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liou HH, Tsai MC, Chen CJ, Jeng JS, Chang YC, Chen SY, et al. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study in Taiwan. Neurology. 1997;48:1583–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.London L, Nell V, Thompson ML, Myers JE. Effects of long-term organophosphate exposures on neurological symptoms, vibration sense and tremor among South African farm workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:18–29. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McConnell R, Keifer M, Rosenstock L. Elevated quantitative vibrotactile threshold among workers previously poisoned with methamidophos and other organophosphate pesticides. Am J Ind Med. 1994;25:325–34. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700250303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGuire V, Longstreth WT, Jr, Nelson LM, Koepsell TD, Checkoway H, Morgan MS, et al. Occupational exposures and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A population-based case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:1076–88. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Misra UK, Prasad M, Pandey CM. A study of cognitive functions and event related potentials following organophosphate exposure. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;34:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrovitch H, Ross GW, Abbott RD, Sanderson WT, Sharp DS, Tanner CM, et al. Plantation work and risk of Parkinson disease in a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1787–92. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pickett W, King WD, Lees RE, Bienefeld M, Morrison HI, Brison RJ. Suicide mortality and pesticide use among Canadian farmers. Am J Ind Med. 1998;34:364–72. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199810)34:4<364::aid-ajim10>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pilkington A, Buchanan D, Jamal GA, Gillham R, Hansen S, Kidd M, et al. An epidemiological study of the relations between exposure to organophosphate pesticides and indices of chronic peripheral neuropathy and neuropsychological abnormalities in sheep farmers and dippers. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:702–10. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.11.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritz B, Yu F. Parkinson’s disease mortality and pesticide exposure in California 1984–1994. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:323–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sack D, Linz D, Shukla R, Rice C, Bhattacharya A, Suskind R. Health status of pesticide applicators: postural stability assessments. J Occup Med. 1993;35:1196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srivastava AK, Gupta BN, Bihari V, Mathur N, Srivastava LP, Pangtey BS, et al. Clinical, biochemical and neurobehavioural studies of workers engaged in the manufacture of quinalphos. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38:65–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stallones L, Beseler C. Pesticide illness, farm practices, and neurological symptoms among farm residents in Colorado. Environ Res. 2002;90:89–97. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stallones L, Beseler C. Pesticide poisoning and depressive symptoms among farm residents. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:389–94. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steenland K, Jenkins B, Ames RG, O’Malley M, Chrislip D, Russo J. Chronic neurological sequelae to organophosphate pesticide poisoning. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:731–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steenland K, Dick RB, Howell RJ, Chrislip DW, Hines CJ, Reid TM, et al. Neurologic function among termiticide applicators exposed to chlorpyrifos. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:293–300. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stephens R, Spurgeon A, Calvert IA, Beach J, Levy LS, Berry H, et al. Neuropsychological effects of long-term exposure to organophosphates in sheep dip. Lancet. 1995;345:1135–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tuchsen F, Jensen AA. Agricultural work and the risk of Parkinson’s disease in Denmark, 1981–1993. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:359–62. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Wijngaarden E. Mortality of mental disorders in relation to potential pesticide exposure. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(5):564–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000063615.59043.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wesseling C, Keifer M, Ahlbom A, McConnell R, Moon JD, Rosenstock L, et al. Long-term neurobehavioral effects of mild poisonings with organophosphate and n-methyl carbamate pesticides among banana workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:27–34. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2002.8.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamel F, Hoppin JA. Association of pesticide exposure with neurologic dysfunction and disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;112(9):950–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Engel LS, O’Meara ES, Schwartz SM. Maternal occupation in agriculture and risk of limb defects in Washington State, 1980–1993. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:193–8. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garry VF, Harkins ME, Erickson LL, Long-Simpson LK, Holland SE, Burroughs BL. Birth defects, season of conception, and sex of children born to pesticide applicators living in the Red River Valley of Minnesota, USA. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:441–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garry VF, Harkins ME, Lyubimov A, Erickson LL, Long L. Reproductive outcomes in the women of the Red River Valley of the North. I. The spouses of pesticide applicators: pregnancy loss, age at menarche, and exposure to pesticides. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2002;65:769–86. doi: 10.1080/00984100290071333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loffredo CA, Silbergeld EK, Ferencz C, Zhang J. Association of transposition of the great arteries in infants with maternal exposures to herbicides and rodenticides. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:529–36. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shaw GM, Wasserman CR, O’Malley CD, Nelson V, Jackson RJ. Maternal pesticide exposure from multiple sources and selected congenital anomalies. Epidemiology. 1999;10:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garcia-Rodríguez J, Garcia-Martin M, Nogueras-Ocana M, de Dios Luna-del-Castillo J, Espigares-Garcia M, Olea N, et al. Exposure to pesticides and cryptorchidism: geographical evidence of a possible association. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:1090–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.104-1469503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcia AM, Benavides FG, Fletcher T, Orts E. Paternal exposure to pesticides and congenital malformations. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:473–80. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garcia AM, Fletcher T, Benavides F, Orts E. Parental agricultural work and selected congenital malformations. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:64–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rojas A, Ojeda ME, Barraza X. [Congenital malformations and pesticide exposure] Revista Medica Chile. 2000;128:399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Medina-Carrilo L, Rivas-Solis F, Fernandez-Arguelles R. [Risk for congenital malformations in pregnant women exposed to pesticides in the state of Nayarit, Mexico] Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2002;70:538–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kristensen P, Irgens LM, Andersen A, Bye AS, Sundheim L. Birth defects among offspring of Norwegian farmers, 1967–1991. Epidemiology. 1997;8:537–44. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199709000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nurminen T, Rantala K, Kurppa K, Holnberg PC. Agricultural work during pregnancy and selected structural malformations in Finland. Epidemiology. 1995;6:23–30. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weidner IS, Moller H, Jensen TK, Skakkebaek N. Cryptorchidism and hypospadias in sons of gardeners and farmers. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:793–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Crisostomo L, Molina VV. Pregnancy outcomes among farming households of Nueva Ecija with conventional pesticide use versus integrated pest management. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2002;8:232–42. doi: 10.1179/107735202800338812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dimich-Ward H, Hertzman C, Teschke K, Hershler R, Marion SA, Ostry A, et al. Reproductive effects of paternal exposure to chlorophenate wood preservatives in the sawmill industry. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1996;22(4):267–73. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.141. Erratum in: Scand J Work Environ Health 1998;24(5):416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abell A, Juul S, Bonde JP. Time to pregnancy among female greenhouse workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:131–6. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Larsen SB, Joffe M, Bonde JP. Time to pregnancy and exposure to pesticides in Danish farmers. ASCLEPIOS Study Group. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55:278–83. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thonneau P, Larsen SB, Abell A, Clavert A, Bonde JP, Ducot B, et al. Time to pregnancy and paternal exposure to pesticides in preliminary results from Danish and French studies. ASCLEPIOS. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25(Suppl 1):62–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thonneau P, Abell A, Larsen SB, Bonde JP, Joffe M, Clavert A, et al. Effects of pesticide exposure on time to pregnancy: results of a multicenter study in France and Denmark. ASCLEPIOS Study Group. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:157–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sallmen M, Liesivuori J, Taskinen H, Lindbohm ML, Anttila A, Aalto L, et al. Time to pregnancy among the wives of Finnish greenhouse workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29:85–93. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Petrelli G, Figa-Talamanca I. Reduction in fertility in male greenhouse workers exposed to pesticides. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:675–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1015511625099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Cock J, Westveer K, Heederik D, te Velde E, van Kooij R. Time to pregnancy and occupational exposure to pesticides in fruit growers in The Netherlands. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51:693–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.51.10.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Curtis KM, Savitz DA, Weinberg CR, Arbuckle TE. The effect of pesticide exposure on time to pregnancy. Epidemiology. 1999;10:112–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tielemans E, Burdorf A, te Velde ER, Weber RF, van Kooij RJ, Veulemans H, et al. Occupationally related exposures and reduced semen quality: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:690–6. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tielemans E, van Kooij R, Looman C, Burdorf A, te Velde E, Heederik D. Paternal occupational exposures and embryo implantation rates after IVF. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:690–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00720-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smith EM, Hammonds-Ehlers M, Clark MK, Kirchner HL, Fuortes L. Occupational exposures and risk of female infertility. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39:138–47. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199702000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tomenson JA, Taves DR, Cockett AT, McCusker J, Barraj L, Francis M, et al. An assessment of fertility in male workers exposed to molinate. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41:771–87. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abell A, Ernst E, Bonde JP. Semen quality and sexual hormones in greenhouse workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:492–500. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harkonen K, Viitanen T, Larsen SB, Bonde JP, Lahdetie J. Aneuploidy in sperm and exposure to fungicides and lifestyle factors. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1999;34:39–46. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(1999)34:1<39::aid-em6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Larsen SB, Spano M, Giwercman A, Bonde J. Semen quality and sex hormones among organic traditional Danish farmers. AESCEPIOS Study Group. Occup Environ Med. 1999;56:1139–44. doi: 10.1136/oem.56.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Potashnik G, Porath A. Dibromochloropropane (DBCP): a 17-year reassessment of testicular function and reproductive performance. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37:1287–92. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199511000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Recio R, Robbins WA, Borja-Aburto V, Moran-Martinez J, Froines JR, Hernandez RM, et al. Organophosphorous pesticide exposure increases the frequency of sperm sex null aneuploidy. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:1237–40. doi: 10.1289/ehp.011091237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Oliva A, Giami A, Multigner L. Environmental agents and erectile dysfunction: a study in a consulting population. J Androl. 2002;23:546–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oliva A, Spira A, Multigner L. Contribution of environmental factors to the risk of male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1768–76. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.8.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Padungtod C, Hassold TJ, Millie E, Ryan LM, Savitz DA, Christinani DC, et al. Sperm aneuploidy among Chinese pesticide factory workers: scoring by the FISH method. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36:230–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199908)36:2<230::aid-ajim2>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Greenlee AR, Arbuckle TE, Chyou PH. Risk factors for female infertility in an agricultural region. Epidemiology. 2003;14:429–36. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000071407.15670.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Heacock H, Hogg R, Marion SA, Hershler R, Teschke K, Dimich-Ward H, et al. Fertility among a cohort of male sawmill workers exposed to chlorophenate fungicides. Epidemiology. 1998;9:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barker D, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmone D. Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effect and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1235–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dabrowski S, Hanke W, Polanska K, Makowiec-Dabrowska T, Sobala W. Pesticide exposure and birthweight: an epidemiological study in Central Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2003;16:31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hanke W, Romitti P, Fuortes L, Sobala W, Mikulski M. The use of pesticides in a Polish rural population and its effect on birth weight. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76:614–20. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hourani L, Hilton S. Occupational and environmental exposure correlates of adverse live-birth outcomes among 1032 US Navy women. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:1156–65. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Karmaus W, Wolf N. Reduced birthweight and length in the offspring of females exposed to PCDFs, PCP, and lindane. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:1120–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.951031120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kristensen P, Irgens LM, Andersen A, Bye AS, Sundheim L. Gestational age, birth weight, and perinatal death among births to Norwegian farmers, 1967–1991. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:329–38. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Munger R, Isacson P, Hu S, Burns T, Hanson J, Lynch CF, et al. Intrauterine growth retardation in Iowa communities with herbicide-contaminated drinking water supplies. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;105:308–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Levario-Carrillo M, Amato D, Ostrosky-Wegman P, Gonzalez-Horta C, Corona Y, Sanin LH. Relation between pesticide exposure and intrauterine growth retardation. Chemosphere. 2004;55(10):1421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Perera FP, Rauh V, Tsai WY, Kinney P, Camann D, Barr D, et al. Effects of transplacental exposure to environmental pollutants on birth outcomes in a multiethnic population. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:201–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Arbuckle TE, Lin Z, Mery LS. An exploratory analysis of the effect of pesticide exposure on the risk of spontaneous abortion in an Ontario farm population. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:851–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Arbuckle TE, Savitz DA, Mery LS, Curtis KM. Exposure to phenoxy herbicides and the risk of spontaneous abortion. Epidemiology. 1999;10:752–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gerhard I, Daniel V, Link S, Monga B, Runnebaum B. Chlorinated hydrocarbons in women with repeated miscarriages. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:675–81. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jarrell J, Gocmen A, Foster W, Brant R, Chan S, Sevcik M. Evaluation of reproductive outcomes in women inadvertently exposed to hexachlorobenzene in southeastern Turkey in the 1950s. Reprod Toxicol. 1998;12:469–76. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(98)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Petrelli G, Figa-Talamanca I, Tropeano R, Tangucci M, Cini C, Aquilani S, et al. Reproductive male-mediated risk: spontaneous abortion among wives of pesticide applicators. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:391–3. doi: 10.1023/a:1007630610911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Savitz DA, Arbuckle TE, Kaczor D, Curtis KM. Male pesticide exposure and pregnancy outcome. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:1025–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bell EM, Hertz-Picciotto I, Beaumont JJ. Case-cohort analysis of agricultural pesticide applications near maternal residence and selected causes of fetal death. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:702–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.8.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pastore LM, Hertz-Picciotto I, Beaumont JJ. Risk of stillbirth from occupational and residential exposures. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:511–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.7.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gerhard I, Frick A, Monga B, Runnebaum B. Pentachlorophenol exposure in women with gynecological and endocrine dysfunction. Environ Res. 1999;80:383–8. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Levario-Carrillo M, Feria-Velasco A, De Celis R, Ramos-Martinez E, Cordova-Fierro L, Solis FJ. Parathion, a cholinesterase-inhibiting pesticide induces changes in tertiary villi of placenta of women exposed: a scanning electron microscopy study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2001;52:269–75. doi: 10.1159/000052989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jarrell JF, Gocmen A, Akyol D, Brant R. Hexachlorobenzene exposure and the proportion of male births in Turkey 1935–1990. Reprod Toxicol. 2002;16:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(01)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.McGready R, Simpson JA, Htway M, White NJ, Nosten F, Lindsay SW. A double blind randomized therapeutic trial of insect repellents for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:137–8. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zeljezic D, Garaj-Vrhovac V. Chromosomal aberration and single cell gel electrophoresis (Comet) assay in the longitudinal risk assessment of occupational exposure to pesticides. Mutagenesis. 2001;16:359–63. doi: 10.1093/mutage/16.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hagmar L, Bonassi S, Stromberg U, Brogger A, Knudsen LE, Norpa H, et al. Chromosomal aberrations in lymphocytes predict human cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Antonucci GA, de Syllos Colus IM. Chromosomal aberrations analysis in a Brazilian population exposed to pesticides. Teratogen Carcinogen Mutagen. 2000;20:265–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Au WW, Sierra-Torres CH, Cajas-Salazar N, Shipp BK, Legator MS. Cytogenetic effects from exposure to mixed pesticides and the influence from genetic susceptibility. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:501–55. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Carbonell E, Xamena N, Creus A, Marcos R. Cytogenetic biomonitoring in a Spanish group of agricultural workers exposed to pesticides. Mutagenesis. 1993;8:511–7. doi: 10.1093/mutage/8.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Carbonell E, Valbuena A, Xamena N, Creus A, Marcos R. Temporary variations in chromosomal aberrations in a group of agricultural workers exposed to pesticides. Mutation Res. 1995;344:127–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(95)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Garaj-Vrhovac V, Zeljezic D. Assessment of genome damage in a population of Croatian workers employed in pesticide production by chromosomal aberration analysis, micronucleus assay and Comet assay. J Appl Toxicol. 2002;22:249–55. doi: 10.1002/jat.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gregio D’Arce LP, Colus IM. Cytogenetic and molecular biomonitoring of agricultural workers exposed to pesticides in Brazil. Teratogen Carcinogen Mutagen. 2000;20:161–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hoyos LS, Carvajal S, Solano L, Rodriguez J, Orozco L, Lopez Y, et al. Cytogenetic monitoring of farmers exposed to pesticides in Colombia. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(Suppl 3):535–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Joksic G, Vidakovic A, Spasojevic-Tisma V. Cytogenetic monitoring of pesticide sprayers. Environ Res. 1997;75:113–8. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1997.3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kaioumova DF, Khabutdinova LK. Cytogenetic characteristics of herbicide production workers in Ufa. Chemosphere. 1998;37:1755–9. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(98)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kourakis A, Mouratidou M, Barbouti A, Dimikiotou M. Cytogenetic effects of occupational exposure in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of pesticide sprayers. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:99–101. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lander BF, Knudsen LE, Gamborg MO, Jarventaus H, Norppa H. Chromosome aberrations in pesticide-exposed greenhouse workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:436–42. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mohammad O, Walid AA, Ghada K. Chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes from two groups of workers occupationally exposed to pesticides in Syria. Environ Res. 1995;70:24–9. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1995.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Paz-y-Mino C, Bustamante G, Sanchez ME, Leone PE. Cytogenetic monitoring in a population occupationally exposed to pesticides in Ecuador. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1077–80. doi: 10.1289/ehp.110-1241062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Varona M, Cardenas O, Crane C, Rocha S, Cuervo G, Vargas J. Cytogenetic alterations in workers exposed to pesticides in floriculture in Bogota [Spanish] Biomedica. 2003;23:141–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bolognesi C. Genotoxicity of pesticides: a review of human biomonitoring studies. Mutation Res. 2003;543:251–72. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(03)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Colosio C, Tiramani M, Maroni M. Neurobehavioral effects of pesticides: state of the art. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:577–91. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Whyatt RM, Rauh V, Barr DB, Camann DE, Andrews HF, Garfinkel R, et al. Prenatal insecticide exposures and birth weight and length among an urban minority cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1125–32. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Williams MK, Barr DB, Camann DE, Cruz LA, Carlton EJ, Borjas M, et al. An intervention to reduce residential insecticide exposure during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(11):1684–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Evans WE, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics—drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(6):538–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Berkowitz GS, Wetmur JG, Birman-Deych E, Obel J, Lapinski RH, Godbold JH, et al. In utero pesticide exposure, maternal paraoxanase activity and head circumference. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(3):388–91. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Pesticide Free Ontario, Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, Oracle Poll. Survey report. Toronto, ON: Oracle Poll; 2007. [Accessed 2007 September 13]. Available from: www.flora.org/healthyottawa/PFO%20CAPE%20Ont%20Poll%202007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment. CAPE position statement on pesticides. Toronto, Ont: Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment; 2000. [Accessed 2007 August 7]. Available from: http://www.cape.ca/toxics/pesticidesps.html. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sear M, Walker CR, van der Jagt RH, Claman P. Pesticide assessment: protecting public health on the home turf. Pediatr Child Health. 2006;11(4):229–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Buka I, Rogers WT, Osornio-Vargas AR, Hoffman H, Pearce M, Li YY. Parents and professionals ranked pesticides in water as an environmental concern second only to ETS. Pediatr Child Health. 2006;11(4):235–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Arya N. Pesticides and human health: why public health officials should support a ban on non-essential residential use. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(2):89–92. doi: 10.1007/BF03403667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health. Pesticides. In: Etzel RA, editor. Pediatric environmental health. 2. Elk Grove Village Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003. pp. 323–59. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ontario College of Family Physicians. Pesticides and your health…. Information from your family doctor [patient information brochure] Toronto, Ont: Ontario College of Family Physicians; 2006. [Accessed 2007 August 7]. Available from: www.ocfp.on.ca/local/files/EHC/Pesticide%20brochure.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Marshall L, Weir E, Abelsohn A, Sanborn M. Identifying and managing environmental health effects: taking an exposure history. CMAJ. 2002;166:1049–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lessenger JE. Fifteen years of experience in cholinesterase monitoring of insecticide applicators. J Agromed. 2005;10(3):49–56. doi: 10.1300/j096v10n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Mandel JH, Carr WP, Hillmer T, Leonard PR, Halberg JU, Sanderson WT, et al. Factors associated with safe use of agricultural pesticides in Minnesota. J Rural Health. 1996;12(4 Suppl):301–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1996.tb00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Keifer MC. Effectiveness of interventions in reducing pesticide overexposure and poisonings. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(4 Suppl):80–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]