Abstract

QUESTION

My patient has severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). I am having difficulty treating her, as nothing she has tried so far has been really effective. I heard that there is some new information regarding the treatment of this condition.

ANSWER

Even a less severe case of NVP can have serious adverse effects on the quality of a woman’s life, affecting her occupational, social, and domestic functioning, and her general well-being; therefore, it is very important to treat this condition appropriately and effectively. There are safe and effective treatments available. We have updated Motherisk’s NVP algorithm to include recent relevant published data, and we describe some other strategies that deal with secondary symptoms related to NVP.

RÉSUMÉ

QUESTION

Une de mes patientes souffre de graves nausées et vomissements de la grossesse. J’ai de la difficulté à la traiter parce que rien de ce qu’elle a essayé jusqu’à présent n’est vraiment efficace. J’ai entendu dire qu’il y a avait du nouveau concernant le traitement de ce problème.

RÉPONSE

Même dans les cas les moins graves, les nausées et les vomissements de la grossesse peuvent sérieusement nuire à la qualité de vie d’une femme, sur le plan professionnel, social et domestique, et à son bien-être général. Il est très important de traiter ce problème de manière appropriée et efficace. Il existe des traitements sûrs et efficaces. Nous avons mis à jour l’algorithme de Motherisk sur les nausées et vomissements de la grossesse, qui inclut toutes les données pertinentes récemment publiées, et nous décrivons certaines autres stratégies pour prendre en charge les symptômes secondaires associés à ce problème.

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) is the most common medical condition of pregnancy, affecting up to 80% of all pregnant women to some degree. In most cases, it subsides by the 16th week of pregnancy, although up to 20% of women continue to have symptoms throughout pregnancy. Severe NVP (hyperemesis gravidarum) affects less than 1% of women, but it can be debilitating, sometimes requiring hospitalization and rehydration.1 Women suffer not only physically, but also psychologically, which has been documented in a number of studies.2–4 In addition, some women have decided to terminate their pregnancies rather than tolerate the severe symptoms.5

Pharmacotherapy

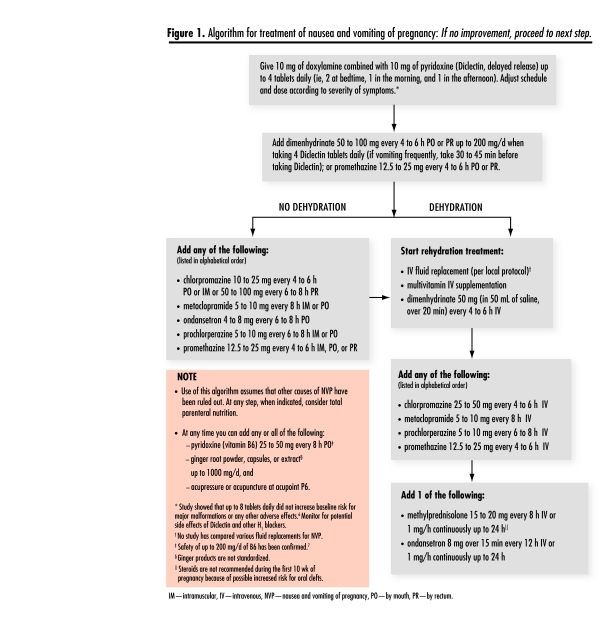

We systematically reviewed the literature pertaining to the symptomatic treatment of NVP from January 1998 to September 2006. The updated algorithm includes this recent relevant published data (Figure 16,7). The drug of choice for treatment in Canada remains Diclectin, the delayed-release combination ofdoxylamine andvitamin B6.8

Figure 1.

Algorithm for treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: If no improvement, proceed to next step.

Other pharmacologic treatments with relatively good safety profiles and varying degrees of effectiveness include antihistamines, ondansetron, phenothiazines, metoclopramide, and corticosteroids.9–12 Herbal products such as vitamin B6 and ginger have also been used safely with varying degrees of effectiveness.7,13–17

Nonpharmacologic treatments

Acupressure and acupuncture at acupoint P6 have been used with varying degrees of effectiveness.12,18

Overcoming secondary symptoms

There are several strategies that have been helpful in dealing with secondary symptoms related to NVP.

Diet

Mixing solids and liquids can increase nausea and vomiting because it can make the stomach feel fuller and, in some women, can cause gas, bloating, and acid reflux. Eating small portions every 1 to 2 hours and eating and drinking separately can be helpful. For example, eat a small portion of food, wait 20 to 30 minutes, then take some liquid.

Remind women that they should eat whatever they can tolerate. Other than in the case of severe malnutrition, fetuses generally receive the nutrition they require—sometimes to the detriment of the mother. For example, the calcium depletion from the fetus can cause a mother’s teeth to decay.

There are supplements on the market that the mother can consume if she is unable to digest a full meal, such as liquid supplements, puddings, and protein bars to replace the lack of essential maternal nutrients.

Fluids

A pregnant woman should try to consume at least 2 litres of fluids daily in small amounts taken frequently. Colder fluids, including ice chips and Popsicles, appear to be easier to tolerate and can decrease the metallic taste in the mouth. There are also commercial products available that maintain the electrolyte balance (sports drinks, etc).

Prenatal vitamins

Vitamins can worsen nausea, primarily because of the iron content and large size. The most common side effects from using prenatal vitamins are constipation, nausea, and vomiting. In the first trimester, a woman can take folic acid alone or take a multivitamin that does not contain iron, as this form does not appear to increase NVP. Later on in the pregnancy when the NVP subsides, she can resume taking her regular multivitamin.

Antacids

Conditions such as heartburn, acid reflux, indigestion, gas, or bloating can also exacerbate NVP and can be very uncomfortable. It is important that these symptoms are treated effectively. Minor symptoms can be treated with antacids containing calcium carbonate; however, if these are not effective, histamine (H2) blockers and proton pump inhibitors are safe to take.19,20

In addition, there are over-the-counter products available that can help with excess gas and bloating. Some women have reported becoming lactose-intolerant during pregnancy; they should switch to lactose-free products. There is also some evidence that effectively treating Helicobacter pylori with antibiotics can mitigate the symptoms of NVP.21,22

Fibre for constipation

Women who do not consume enough fibre should try to increase their fibre intake by eating well-tolerated high-fibre foods (eg, cereal, dried fruit). If this is not effective, they can try over-the-counter products such as psyllium and a stool softener (eg, docusate sodium).

Spitting and mouth washing for excessive saliva

Women should be advised not to swallow excessive saliva, as this can increase the symptoms of NVP. Spitting out the saliva and frequent mouth washing can be helpful.

Management

Because NVP affects a large number of pregnant women, some with serious consequences, it cannot be ignored, especially when there are safe and effective treatments available. Inquiring about NVP when interviewing pregnant women during their first visits to health care providers is an essential part of the history. Many women do not volunteer this information because their symptoms might have been minimized by others, or they have been informed that it is a normal part of pregnancy and something they have to tolerate.

Health care providers should be aware of the evidence-based information regarding various treatment modalities and offer them to their patients when appropriate. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy manifests itself differently in each woman, and its management should be tailored for each individual.

Nausea alone should not be minimized, as this can affect the quality of life as much as—or more than—vomiting. Nausea treatments can be either pharmacologically based or holistic, or an effective combination of both. Timing of NVP treatment is also important, as early treatment can prevent a more severe form from occurring, reducing the possibility of hospitalization, time lost from paid employment, and emotional and psychological problems. It is important that women and their health care providers understand that the benefits of safe and effective NVP treatment predominantly outweigh any potential or theoretical risks to the fetus; thus, all treatment options should be considered.

Conclusion

Since we developed the algorithm in 2002,23 there has been some new evidenced-based information published on the safety of various pharmacotherapy treatments, as well as some other strategies that we have found helpful for these women. As family physicians are often the first health care providers women approach when their pregnancy is confirmed, it is important they have this information to assist these women during this extremely unpleasant stage of pregnancy.

References

- 1.Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead AM, Jagger C. A prospective study of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43(371):245–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzotta P, Stewart D, Atanackovic G, Koren G, Magee LA. Psychosocial morbidity among women with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: prevalence and association with anti-emetic therapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21(3):129–36. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou FH, Lin LL, Cooney AT, Walker LO, Riggs MW. Psychosocial factors related to nausea, vomiting, and fatigue in early pregnancy. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(2):119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swallow BL, Lindow SW, Masson EA, Hay DM. Psychological health in early pregnancy: relationship with nausea and vomiting. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24(1):28–32. doi: 10.1080/01443610310001620251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzotta P, Stewart DE, Koren G, Magee LA. Factors associated with elective termination of pregnancy among Canadian and American women with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22(1):7–12. doi: 10.3109/01674820109049946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atanackovic G, Navioz Y, Moretti ME, Koren G. The safety of higher than standard dose of doxylamine-pyridoxine (Diclectin) for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41(8):842–5. doi: 10.1177/00912700122010735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrim A, Boskovic R, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, Garcia Bournissen F, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome following use of large doses of vitamin B6 in the first trimester. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(8):749–51. doi: 10.1080/01443610600955826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duchesnay. Product center—Diclectin [website] Laval, QC: Duchesnay; 2006. [Accessed 2007 October 23]. Available from: http://www.duchesnay.com/product_diclectin.html. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einarson A, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, Kennedy D, Tan MP, Koren G. The safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a prospective comparative study. BJOG. 2004;111(9):940–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asker C, Norstedt Wikner B, Kallen B. Use of antiemetic drugs during pregnancy in Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(12):899–906. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0055-1. Epub 2005 November 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berkovitch M, Mazzota P, Greenberg R, Elbirt D, Addis A, Schuler-Faccini L, et al. Metoclopramide for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a prospective multicenter international study. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19(6):311–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jewell D, Young G. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD000145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portnoi G, Chng LA, Karimi-Tabesh L, Koren G, Tan MP, Einarson A. Prospective comparative study of the safety and effectiveness of ginger for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1374–7. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00649-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thaver D, Saeed MA, Bhutta ZA. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD000179. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000179.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordeng H, Havnen GC. Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(6):371–80. doi: 10.1002/pds.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borrelli F, Capasso R, Aviello G, Pittler MH, Izzo AA. Effectiveness and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):849–56. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154890.47642.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills E, Duguoa JJ, Perri D, Koren G. Herbal medicines in pregnancy and lactation: an evidence-based approach. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heazell A, Thorneycroft J, Walton V, Etherington I. Acupressure for the in-patient treatment of nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy: a randomized control trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):815–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garbis H, Elefant E, Diav-Citrin O, Mastroiacovo P, Schaefer C, Vial T, et al. Pregnancy outcome after exposure to ranitidine and other H2-blockers. A collaborative study of the European Network of Teratology Information Services. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;19(4):453–8. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diav-Citrin O, Arnon J, Shechtman S, Schaefer C, van Tonningen MR, Clementi M, et al. The safety of proton pump inhibitors in pregnancy: a multi-centre prospective controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(3):269–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penney DS. Helicobacter pylori and severe nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(5):418–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golberg D, Szilagyi A, Graves L. Hyperemesis gravidarum and Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):695–703. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000278571.93861.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levichek Z, Atanackovic G, Oepkes D, Maltepe C, Einarson A, Magee L, et al. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Evidence-based treatment algorithm. . Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:267–8. 277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]