Abstract

Shooting galleries (SGs) are illicit off-street spaces close to drug markets used for drug injection. Supervised injecting facilities (SIFs) are low threshold health services where injecting drug users (IDUs) can inject pre-obtained drugs under supervision. This study describes SG use in Kings Cross, Sydney before and after the opening of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre (MSIC), Australia’s first SIF. Operational and environmental characteristics of SGs, reasons for SG use, and willingness to use MSIC were also examined. An exploratory survey of SG users (n = 31), interviews with SG users (n = 17), and drug workers (n = 8), and counts of used needles routinely collected from SGs (6 months before and after MSIC) and visits to the MSIC (6 months after MSIC) were triangulated. We found five SGs operated during the study period. Key operational characteristics were 24-h operation, AUS$10 entry fee, 30-min time limit, and dual use for sex work. Key reasons for SG use were to avoid police, a preference not to inject in public, and assistance from SG operators in case of overdose. SG users reported high levels of willingness to use the MSIC. The number of used needles collected from SGs decreased by 69% (41,819 vs. 12,935) in the 6 months after MSIC opened, while MSIC visits increased incrementally. We conclude that injections were transferred from SGs to the MSIC, but SGs continued to accommodate injections and harm reduction outreach should be maintained.

Keywords: Blood-borne virus risk behavior, Injecting drug use, Shooting galleries, Supervised injecting facilities

INTRODUCTION

Injecting drugs in public places is stressful and risky, and demand exists among injecting drug users (IDUs) for relatively safe and private places to use.1–4 One response to this demand is shooting galleries (SGs). These are clandestine off-street places near drug markets where IDUs go to use and sometimes access needles and syringes5 (hereafter collectively referred to as “needles”). SG use has, however, been associated with increased blood-borne virus (BBV) risk behavior and transmission.6–12 The operational and environmental characteristics of SGs, mostly documented in U.S. studies, vary from being anarchic to management by operators with entry fees of cash or small quantities of drugs.13–16 The latter type of SG is the focus of this paper.

SGs have operated in Kings Cross, Sydney’s “red light” district, since the 1990s.17,18 Operating within budget hotels and sex industry premises, rooms are rented to IDUs and sex workers for short periods. In 1994, at least 10 SGs were operating,19 and 1 in 10 IDUs reported their last injection was at an SG.17 However, most of these SGs were closed down in 1995 after being uncovered during the Royal Commission into Police Corruption.18 Subsequent increases in public injecting were reported in the Kings Cross area.20

At least two SGs were reportedly still operating when legislation was passed for the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre (MSIC) trial in July 1999,21 Australia’s first supervised injecting facility (SIF). SIFs are low threshold health services where IDUs can inject pre-obtained drugs in a hygienic environment under professional supervision.22 With a pending legal alternative to SGs, local police indicated that any remaining SGs would be permanently closed down once the MSIC opened (King Cross Police Commander, personal communication, February 2001).

The likely closure of SGs with the opening of the MSIC raised several questions. First, the characteristics of SG operation in Kings Cross had not been examined since the Royal Commission. Secondly, reasons for SG use and the willingness of SG users to use the MSIC had not been established. Finally and most importantly, the capacity of MSIC to absorb SG injections had not been considered in the MSIC evaluation protocol.23

For example, 10 SGs had an estimated total throughput of 40,000 injections in 1994.19 The projected throughput of MSIC was 100 to 200 injections per day. Assuming no changes in average SG throughput and 100% MSIC uptake, the closure of the reported two remaining SGs could displace a minimum of 65 injections to Kings Cross streets per day. Possible implications of this include increased injecting-related harm among displaced IDUs; and wrongful attribution of potential increases in the visibility of drug users, public injecting, and discarded needles to the MSIC attracting more IDUs to Kings Cross.

This study aims to examine (1) characteristics of Kings Cross SGs’ operation; (2) reasons for SG use; (3) willingness of SG users to use the MSIC; and (4) the estimated number of injections at SGs in the 6 months before and after the opening of MSIC and the number of injections at MSIC in the same period.

METHODS

Mixed methods were used. Data were triangulated from: (1) an exploratory survey of SG users; (2) semi-structured interviews with key informants; and (3) counts of used needles collected from SGs and IDU visits to MSIC. The study was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee. A “shooting gallery” was defined as a place where rooms are rented for the purpose of drug injection.

Survey of Shooting Gallery Users

Participants were recruited through the Kings Cross site of the Australian Prevalence Estimation and Treatment Study (APET), a cross-sectional IDU survey, which used a snowball sampling approach undertaken in January 2001.24 All participants (n = 115) were screened and those reporting SG use in the past 6 months were administered a sub-questionnaire, which took 15–25 min to complete. Questions included drugs injected, injection frequency and locations, SGs’ operational and environmental characteristics, and willingness to use the planned MSIC. Participants unaware of the MSIC were given a brief background description. Participants received AUS$20 compensation for their time. Data were coded and analyzed descriptively using SPSS (Version 11).

Key Informant Interviews

Semi-structured key informant interviews25 were undertaken by members of the research team (JK, ES, MH) with 17 IDUs and eight local drug workers in March 2001. The study was introduced as anonymous university research looking at SG use in Kings Cross before and after MSIC. Questions related to operational and environmental characteristics of Kings Cross SGs and IDU reasons for SG use and their willingness to use MSIC. IDU key informants were recruited using snowball sampling methods via a peer recruiter.26 The eligibility criterion was use of a shooting gallery in the past 6 months, and we aimed to recruit a cross-section of IDUs based on gender, age, primary drug, and injection frequency. Drug workers were recruited from local agencies including the needle exchange, the IDU primary care clinic, a drop-in center, and the needle clean up team. They were selected based on their close professional contact with IDUs and their manager’s approval. IDUs were interviewed at a local drop-in center, and drug workers, at their workplace. Interviews were 40- to 90-min duration and were recorded and transcribed. IDUs received AUS$20 compensation for their time. A thematic content analysis approach27 was used. Transcripts were coded by three research team members (JK, KD, and ES). Key themes arising in relation to the research questions were agreed, and the data were synthesized manually.

Counts of Used Needles at Shooting Galleries and MSIC Visits

A used needle collected from a SG was taken to be a good indicator of a recent illicit drug injection at that SG. Data were obtained from the local health authority’s needle clean-up team on the number of used needles collected from premises operating SGs. They routinely estimate the number of needles from the volume and weight of collected sharp bins. Monthly needle counts by address were obtained for November 2000 to October 2001 inclusive (6 months before and after the opening of the MSIC on 6 May 2001). Monthly counts of MSIC visits to inject from May to October 2001 inclusive were also obtained and compared to the SGs counts.

RESULTS

Survey Participant and IDU Key Informant Characteristics

Of 115 IDUs screened for the SG users survey, 31 (27%) reported SG use in the past 6 months. Two-thirds were female (n = 21) with a median age of 31.5 years (range 17 to 44 years). Almost all were daily injectors (n = 29), and three quarters (n = 23) reported heroin as their main drug injected. One-third were homeless (n = 10), and two out of five had sex worked in the past month (n = 13). One in five had used SGs daily (n = 6) in the past month.

The 17 IDU key informants comprised 13 males and 4 females. Their median age was 33 years (range 21 to 46 years). Seven were living in unstable accommodation. Frequent (n = 9) and occasional injectors (n = 8) were similar in number, and heroin was the most common primary drug (n = 8) followed by methamphetamine (n = 5) and cocaine (n = 4).

Reasons for Shooting Gallery Use

Regular SG users were characterized by key informants as street-based sex workers and local homeless or “hard core” users. Occasional users included “white collar” “respectable” drug users, and those “from out of town” seeking to purchase drugs.

Safety

The primary reason given for SG use by both survey participants and key informants was safety. SGs were a “safe place” and used to “stay out of trouble”, to avoid being “harassed” by the police, to avoid assault by other drug users, and to receive assistance from SG operators in the case of overdose.

That $10 is security that you’re not going to get busted...have you ever tried having a shot on the street—you’ve got more chance of getting busted or seen. You’ve got plain clothes coppers walking everywhere. It’s a security risk to have a shot on the street, but [the] security risk is cancelled out when you go up to a room. (IDU-KI 13)

Basically [it is] a more safe environment than what is on the street... they come and check on you... you could overdose and lay there for twenty minutes, half an hour and you could be dead. ...on the street in a back lane...no one could know who you are, what you are... the [shooting gallery] system is a lot safer. (IDU-KI 3)

Buying Privacy and Time

SG use also alleviated the “stress” associated with injecting in public, in particular, having privacy and more time to find a vein. Self-respect and respect for others by not injecting in public and “not to be looked on as a disgrace” was a common theme. SGs were also a place for those who had “nowhere else to go” because of homelessness or wishing to conceal their drug use from employers or family.

They’re a good thing in the sense of you’ve got your privacy. You’re not affecting anybody else and no one has to watch you do it. You’re catered for that way, your privacy, and can concentrate on doing the right thing instead of like paranoia...I don’t want anybody knowing my business and like to mind me own business and, you know, I don’t want it in their face. (IDU-KI 17)

Because I’ve shot up so many types of drugs that I’ve collapsed all my arms and veins and crap. It takes me ages to get myself, so I’ve got to sit down and relax. (IDU-KI 7)

Economics

Finally, SG use was seen as economically prudent given the time and effort invested raising the money to buy drugs. The entry fee, however, was also sometimes a barrier to use.

I’d rather go to a room than do it in the street ... If they [the police] get you after you’ve had your shot it’s just a big laugh you know. But if you’re mixing up and they get you then...you turn nasty because you could have been out all day to get that money for that one shot and then some cop comes along and kicks it in the gutter. (IDU-KI 4)

Oh it’s a bit hard. I mean I’ve shot up in the streets a lot you know, because like ten dollars like sometimes it can be ...the difference between you getting on again or not. So, I mean if I’m cased up I’ll use a room. (IDU-KI 7)

Characteristics of Shooting Gallery Operation

Six unique SGs were identified by survey participants: gallery A (n = 14), gallery B (n = 12), gallery C (n = 17), gallery D (n = 5), gallery E (n = 2), and gallery F (n = 3). Galleries A, C, and D operated from budget hotel premises and B, E, and F from sex industry premises. Five of these SGs, A to E, were also identified in the needle counts (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Counts of used needles collected from shooting gallery premises before and after MSIC opened

| Premises | A | B | C | D | E | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before MSIC (Nov 00–Apr01) | 6,945 | 200 | 16,850 | 16,574 | 1,250 | 41,819 |

| After MSIC (May 01–Oct 01) | 4,150 | 375 | 2,550 | 5,450 | 410 | 12,935 |

| Total needles | 11,095 | 575 | 19,400 | 22,024 | 1,660 | 54,754 |

Operational Characteristics

A total of 69 individual reports on the operational characteristics of galleries A to F were provided by survey participants (i.e., some described more than one SG). An entry fee of AUS$10 (91%), 24-h operation (87%), and operators calling the ambulance in case of overdose (90%) were the norm. Enforcement of a 30-min time limit (66%) and operator monitoring of patrons by knocking on the door when the allocated time was nearly expired (74%) were also commonly reported. Experience of police raids (29%) and sterile needle availability (25%) were less frequently reported characteristics.

Rules associated with SG use were described in one in five reports (19%). These included refusal of entry if assessed by the operator to be too intoxicated and to leave the room tidy and to use the sharps bins provided. Operators were also reported to sometimes inquire about what drug was to be injected with a view to closer monitoring of patrons using opioids.

Key informants’ descriptions of SGs’ operational characteristics echoed those of survey participants. SGs were characterized as businesses with a fixed entry fee, room allocation, and a time limit. Sterile needles were available, sometimes for an extra fee. Prospective patrons were not vetted and remained anonymous. Small groups of IDUs who had purchased drugs together would also commonly rent a room together.

You walk in [Venue C] and you just say to the guy at the bottom of the stairs, ‘I’ll have a room thanks’ and he says “10 bucks”, and if you need a fit [needle and syringe] you say to him “have you got any fits”? And he goes “Yeah”, pulls one out for you, gives it to you and just says “Ok”, looks at his book and says “Room 4” or “6” ... and that’s it. You just go up, do what you have to do and come back down and see you later. Don’t sign in, nothing. (IDU-KI 2)

Drugs and Sex Work

The nexus of drug supply and sex work at premises operating SGs was a common theme. These premises were referred to as being a “one stop shop”—a place to score, place to use, place to sell or purchase sex, and for some, also budget accommodation.

We ended up getting some good stuff but we didn’t know where to go and shoot up and then someone told us to go to [Venue B]...there were people coming in left, right and centre. Working girls in their lingerie...drugs and everything going on ...people coming out of the room and people going in the room and then coming out of the room, ... wow, it’s like a factory. (IDU-KI 5)

Response in case of overdose

The assistance provided by SG operators in case of overdose, often contrasted to the lack of assistance or late detection of street-based overdoses, was a pervasive operational theme. Perceptions of SG operators, however, were mixed, some were portrayed as “good” and others as unethical and profit motivated.

If you’re in a room and you drop ... someone finds you. If you’re not dead and basically that happens a lot and then they’ve [operators] got to call the ambulance ... I’ve seen the ambos come...hit ’em with Narcan and try and bring them around or take ‘em to hospital. (IDU-KI 4)

Policing

Police activity at SGs was reportedly not an uncommon occurrence. Some operators were given credit for trying to warn patrons in advance if possible. Police activity, however, was perceived by IDU and drug worker key informants to have a short-term impact on both drug supply on the premises and shooting gallery operation.

All the street people watch where the police go all the time...if we see them going up into [Venue B] well then you think oh well they’re keeping an eye on [Venue B] so we won’t use [Venue B] for a while...we respect the owners of the place as well. To give them a bit of a break so they don’t get harassed all the time and about three or four days later everything is back to running flow again. (IDU-KI 5)

[The number of premises operating SGs] changes frequently. Sometimes there’s a few places will say, “oh I’m sorry ... we don’t use any equipment [disposal bins] now because the police have been around and closed us down”. You know when the police have been up there they’ll say that...But I’ll find as I keep going in ... they’ll say “oh yes, we do actually need a couple of new sharps containers and could you take these away”...some places are open about it and some places are not (DW-KI 4)

Physical Environment

The physical environment of SGs was routinely described as squalid. The combination of injecting and sex work was associated with widespread presence of blood, sexual fluids, vomit, and feces. The potential for needle stick injuries and accidental or intentional reuse of needles was also highlighted because of unsafe disposal.

They’re disgusting. They’re the most unhygienic, dirty, unkempt rooms I’ve ever seen and to charge someone $10...You go in and there is just blood everywhere, there’s vomit... [the sharp bin] is usually overflowing, most people just leave their fits just layin’ on the bench, no lids on them, on the floor, once they’ve had their shot they don’t give a damn...there’s [blood] ... on the floor, dripped onto the floor, on the bench ... in the sink, in the bathroom...it’s horrible. (IDU-KI 2)

Willingness to Use a Medically Supervised Injecting Center

Among survey participants (n = 31), almost all knew of the planned MSIC (n = 29) and two-thirds (n = 21) reported being highly likely to use the MSIC. None rated themselves highly unlikely to use the MSIC.

Similarly, both IDU and drug worker key informants indicated there were high levels of willingness among local IDUs to use the planned MSIC, which was perceived as an attractive alternative to SGs or street-based drug use. The reasons most commonly given were that it would be free, hygienic, and have professional assistance in the case of overdose.

It doesn’t cost. That’s the main factor... 99% would say they would go there and think—well I would go there because I know it’s clean, it’s safe, it’s medically supervised...nothing can go wrong virtually...Why would someone pick to pay $10 to go to a filthy dirty room that you could get hepatitis A just from touching the benches to go to a safe environment? That would be just silly. (IDU-KI 2)

It was stressed that there was constant demand in Kings Cross for safe places to inject and that MSIC would provide a desirable combination of low threshold service contact in a setting where it was acceptable to inject drugs.

People are always looking for somewhere to go to shoot up. You would be inundated if you opened up...people do want a safe place to use ...I don’t enjoy sitting in the gutter ...the most enjoyment I can get from it is like to go to the nicest place I possibly can think of and have me shot...but it’s certainly not in the streets of King Cross or those rooms any more. (IDU-KI 4)

Potential barriers to MSIC use included: “paranoia” about police (e.g., warrant checks) and media surveillance; any perceived inconvenience of MSIC use because of distance from the place of drug purchase or delays to use such as the registration process, especially when “hanging out to use”; not meeting the entry criteria; conflict between MSIC rules and one’s injecting rituals; reticence about supervision; and the nonsmoking policy.

It was suggested the MSIC client base would take time to build as some IDUs would be cautious at first, but uptake would increase once peer networks communicated that MSIC was “ok”.

We’ve talked to lots of users and it’s funny because they’ve said things like, “I don’t want to [use it], it’s going to be really obvious”, you know you walk down there and they’re really scared of what the police will do. They don’t trust that they’re going to be walking there with drugs and the police are going to leave them alone, so there’s a bit of hesitancy about it...they’re worried about the obviousness of going in...especially in the beginning. (DW-KI 3)

It was also highlighted that, even once, MSIC had a client base, there would continue to be demand for SGs because of the limited hours of MSIC operation (8–10 h per day) and the late night injecting patterns of sex workers and binge users of cocaine and methamphetamine.

Remember the MSIC is only going to be open for [limited] hours [in the morning and afternoon]. So I think the other places will still fill that void, especially you know, a lot of sex workers and users are still using really late at night, it’s a 24 hour beat...I think it’s pretty clear that there will still be a demand for other venues (DW-KI 3).

Number of Injections Occurring at Shooting Galleries and MSIC

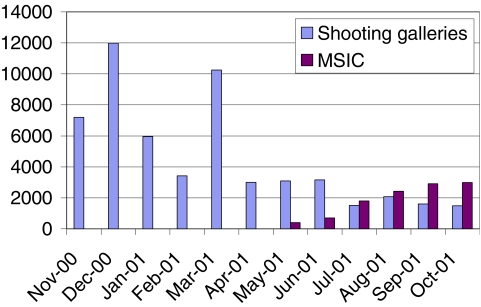

A total of 41,819 used needles were collected from five SGs in the 6 months before the MSIC opened, and 12,935 used needles were collected in the 6 months after MSIC opened, an overall decrease of 69% (Table 1). Galleries C, D, and A accounted for the majority of SG throughput before and after MSIC, but all had large decreases in the number of used needles collected after MSIC opened except gallery B, which was low throughput both before and after MSIC (Table 1). By the third month of MSIC operation, the number of MSIC visits had exceeded the total number of needles collected from SGs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Number of used needles collected from shooting galleries and number of MSIC visits.

DISCUSSION

We found that at least five shooting galleries were operating in Kings Cross in the 6 months before and after the opening of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre. The number of injections at these SGs decreased substantially in the 6 months after the opening of the MSIC, while the number of visits to MSIC consistently increased.

The characteristics of Kings Cross SG operation were unchanged from the mid-1990s19,28 and appear to be similar to Chicago’s “cash galleries”14 and San Francisco’s “formal galleries”15 in their business-like operation and entry fees. The main users of Kings Cross SGs were street-based IDUs and sex workers. Similar to U.S. studies, primary reasons given for SG use included safety from police, privacy, and assistance in case of overdose.15,16,29–31 However, in contrast to U.S. studies, needle availability was not a primary reason for SG use,15,16,29–31 and there was no evidence of needles being rented or indiscriminately shared as found elsewhere.5,7,8,10–12,30,32–37

Willingness to use MSIC was high among SG users, and MSIC was perceived as an attractive and cost-free alternative to SGs. As found in other SIF feasibility studies, this was conditional on MSIC being near the drug market, low threshold, hygienic, safe from police intervention, and offering assistance in case overdose.38,39

This study was limited by the survey’s small sample size and day time only fieldwork; thus, the findings may not be representative of SG users, especially primary cocaine users and sex workers who primarily use in the evening.40 There was, however, strong convergence between the findings of the survey and the key informant interviews, which allows for greater confidence in both data sets. In addition, the needle counts are only an indicator of the number of injections taking place at SGs during the study period, and this may have been impacted by changes in patterns of drug use in 2001 due to the Australian heroin shortage.41–43

The study findings highlight how Kings Cross SGs could be both a “safe” and “risk” environment.14,19,30 Safer than injecting in public places because of being off-street, the onsite availability of sterile needles and sharp bins facilitated by local NSP outreach44 and operator responsiveness in cases of overdose. However, SG users are at risk of exposure to BBVs and other pathogens via environmental contamination with blood, sexual fluids, feces and unsafe syringe disposal in spite of sharp bins. Moreover, SGs remain precarious injecting environments because of their unregulated operation and links to drug supply and associated police intervention.

We conclude that the majority of injections from SGs were transferred to MSIC within its first 6 months of operation, but SGs continued to accommodate injections in Kings Cross. This probably reflects ongoing demand for off-street places to inject outside of MSIC hours of operation. In addition, the dual use of SGs by street-based sex workers highlights the important ongoing role of SGs to this vulnerable group. Taken together, our findings reinforce the importance in Kings Cross and similar settings of maintaining harm reduction outreach to SGs alongside SIF operation, as SIFs are unlikely to achieve total injection coverage.45 Furthermore, as SIFs are a niche intervention,46 the need remains to acknowledge and strengthen safer environment interventions embedded within existing spatial relations.4,47

Acknowledgments

This was an unfunded study, and data collection was made possible by the generosity of investigators from the APET and Dealing with Risk studies, in particular, Dr. Erica Southgate, Dr. Carolyn Day, and Ms. Anne Maree Weatherall. We also gratefully acknowledge the APET interviewers, Mr. Max Hopwood for his assistance with key informant interviews, the SESAHS Needle Clean Up Team, Dr. Ingrid van Beek, Director of KRC and MSIC, for her support of the study, and Dr. Tim Rhodes for comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

References

- 1.Kerr T, Small W, Wood E. The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: a review of the evidence. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16(4):210–220. [DOI]

- 2.Rhodes T. The “risk environment”: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94. [DOI]

- 3.Maher L, Dixon D. Policing and public health: law enforcement and harm minimisation in a street-level drug market. Br J Criminol. 1999;39:488–512. [DOI]

- 4.Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman S, Strathdee S. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1026–1044. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR. Shooting galleries and AIDS: infection probabilities and “tough” policies. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(2):142–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Latkin CA, Mandell W, Vlahov D, et al. My place, your place, and no place: behavioural settings as a risk factor for HIV-related injection practices of drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Community Psychol. 1994;22(3):415–430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Shapshak P, Fujimura RK, Page JB, et al. HIV-1 RNA load in needles/syringes from shooting galleries in Miami: a preliminary laboratory report. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:153–157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Battjes RJ, Pickens RW, Haverkos HW, et al. HIV risk factors among injecting drug users in 5 U.S. cities. AIDS. 1994;8(5):681–687. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Friedman S, Jose B, Deren S, et al. Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among out of treatment drug injectors in high prevalence and low prevalence cities. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:864–874. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Chitwood D, McCoy C, Incardi J, et al. HIV Seropositivity of needles for shooting galleries in South Florida. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:150–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Marmor M, Des Jarlais DC, Cohen H, et al. Risk factors for infection with human immunodeficiency virus among intravenous drug abusers in New York City. AIDS. 1987;1(1):39–44. [PubMed]

- 12.Nemoto T. Behavioural characteristics of seroconverted intravenous drug users. Int J Addict. 1992;27(12):1413–1421. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Carlson R. Shooting galleries, dope houses, and injection doctors: examining the social ecology of HIV risk behaviors among drug injectors in Dayton, Ohio. Human Organ. 2000;59:325–333.

- 14.Ouellet LJ, Jimenez A, Johnson W, et al. Shooting galleries and HIV disease: variations in places for injecting illicit drugs. Crime Delinq. 1991;37(1):64–85. [DOI]

- 15.Murphy S, Waldorf D. Kickin’ down to the street doc: shooting galleries in the San Francisco Bay area. Contemp Drug Probl. 9–29 1991;1991(18):1.

- 16.Longshore D. Prevalence and circumstances of drug injection at Los Angeles shooting galleries. Crime Delinq. 1996;42(1):21–35. [DOI]

- 17.Rutter S, Dolan K, Wodak A. Rooms for rent: injecting and harm reduction in Sydney. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1997;21:105. [PubMed]

- 18.Wood JRT. Royal Commission Into the New South Wales Police Service. Sydney: Government of New South Wales; 1997.

- 19.Parliament of New South Wales. Report on the establishment or trial of safe injecting rooms. Joint Select Committee into Safe Injecting Rooms. Sydney: Parliament of New South Wales; 1998.

- 20.Collins L, van Beek I. Caught in the Crossfire. Paper presented at: 28th Australian Public Health Association Conference, 1996; Perth, Australia.

- 21.Parliament of New South Wales. Drug Summit Legislative Response Act. 67; 1999.

- 22.Dolan K, Kimber J, Fry C, et al. Drug consumption facilities in Europe and the establishment of supervised injecting centres in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2000;19:337–346.

- 23.MSIC Evaluation. Evaluation Protocol for the trial a Medically Supervised Injecting Centre in Kings Cross. Sydney: University of New South Wales; 2001.

- 24.Day C, Ross J, White B, et al. Australian prevalence and estimation of treatment study: New South Wales Report. Sydney: University of New South Wales; 2002. NDARC Technical Report No. 127.

- 25.Marshall MN. The key informant technique. Fam Pract. 1996;13(1):92–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Power R, Hartnoll R, Daviaud E. Drug injecting, AIDS, and risk behaviour: potential for change and intervention strategies. Br J Addict. 1988;83:649–654. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and Thematic Analysis. In: Marks D, Yardley L, eds. Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology. London: Sage Publications; 2004.

- 28.Wodak A, Symonds A, Richmond R. The role of civil disobedience in drug policy reform: how an illegal “safer injection room” led to a sanctioned “medically supervised injecting centre”. J Drug Issues. 2003;33(3):609–624.

- 29.Latkin CA, Mandell W, Vlahov D, et al. Personal network characteristics as antecedents to needle-sharing and shooting gallery attendance. Soc Netw. 1995;17:219–228. [DOI]

- 30.Page JB, Smith PC, Kane N. Shooting galleries, their proprietors, and implications for prevention of AIDS. Drugs Soc. 1990;5:69–85. [DOI]

- 31.Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Cohn S, et al. Risk factors for shooting gallery use and cessation among intravenous drug users. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(10):1291–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Robles R, Marrero CA, Reyes JC, et al. Risk behaviours, HIV seropositivity, and tuberculosis infection in injecting drug users who operate shooting galleries in Puerto Rico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Human Retrovirol. 1998;17(5):477–483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Colon HM, Robles R, Sahai H, et al. Changes in HIV risk behaviors among intravenous drug users in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Br J Addict. 1992;87(4):585–590. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC. HIV among drug injectors: the epidemic and the response. AIDS Care. 1991;3(3):239–250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Nemoto T, Foster K, Brown L. Effect of psychological factors on risk behavior of human inmmunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among intravenous drug users (IVDUs). Int J Addict. 1991;26(4):441–456. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Kaplan EH. Needles that kill: modelling human immunodeficiency virus transmission via shared drug injection equipment in shooting galleries. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(2):289–298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Strathdee S, Galai N, Safaiean M, et al. Sex differences in risk factors for HIV seroconversion among injection drug users: a 10-year perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1281–1288. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Kerr T, Wood E, Small D, et al. Potential use of safer injecting facilities among injection drug users in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. CMAJ, Can Med Assoc J. 2003;169(8):759–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Fry C, Fox S, Rumbold G. Establishing safe injecting rooms in Australia: attitudes of injecting drug users. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999;23:501–504. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Kaye S, Darke S, McKetin R. The Prevalence, Patterns and Harms of Cocaine Use Among Injecting and Non-Injecting Drug Users in Sydney. Sydney: University of New South Wales; 2000. NDARC Technical Report No. 99.

- 41.Topp L, Day C, Degenhardt L. Changes in patterns of drug injection concurrent with a sustained reduction in the availability of heroin in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:275–286. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Day C, Degenhardt L, Gilmour S, et al. Effects of reduction in heroin supply on injecting drug use: analysis of data from needle and syringe programmes. Br Med J. 2004;329:428–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Day C, Topp L, Rouen D, et al. Decreased heroin availability in Sydney Australia in early 2001. Addiction. 2003;98:93–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.van Beek I. Approaches to injecting drug use in Kings Cross: a review of the last 10 years. NSW Public Health Bull. 2000;11(4):54–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Kimber J, Hickman M, Degenhardt L, et al. Estimating the size of the local IDU population using client visits to the Sydney medically supervised injecting centre. Paper presented at: 16th International Conference on the reduction of drug related harm; 20–24 March, 2005; Belfast, Northern Ireland.

- 46.Kimber J, Dolan K, van Beek I, et al. Drug consumption facilities: an update since 2000. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T, et al. Methods for assessing HIV and HIV risk among IDUs and for evaluating interventions. Int J Drug Policy. 2005;16(Suppl 1):7–20.