Abstract

The mechanisms and interplay of coactivators that underlie transcription activation is a critical avenue of investigation in biology today. Using nuclear receptor mediated transcription activation as a model, the nature of coactivator recruitment and chromatin modifications have been found to be highly dynamic. Progress in understanding the kinetics and regulation of coactivator recruitment, and subsequent effects on transcriptional readout, has greatly improved our understanding of nuclear receptor mediated transcription, the subject of discussion in this ‘At the Cutting Edge’ review.

Introduction

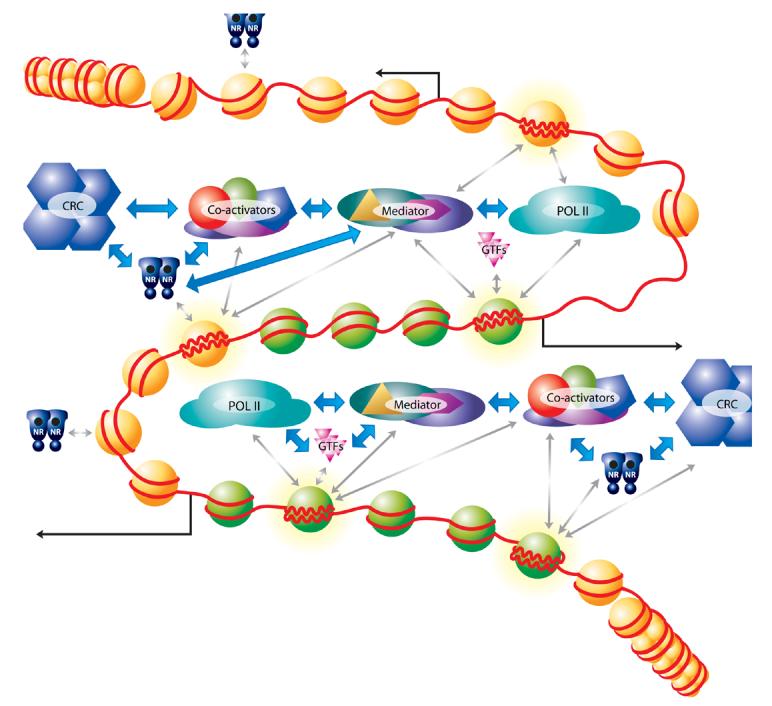

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are ligand responsive transcription factors that play vital roles in many biological processes such as growth, development and homeostasis by regulating their target gene expression (Mangelsdorf et al., 1995; Tsai and O'Malley, 1994). Decades of work have revealed that gene activation and repression requires myriad of factors including various combination of transcription factors, co-activators and co-repressors, general transcription factors (GTFs) and the RNA polymerase (RNAPII) machinery itself (Kinyamu and Archer, 2004; Perissi and Rosenfeld, 2005). Complexity of gene regulation is further increased by the realization that transcription factors must regulate gene expression from the genome that is compacted in the form of chromatin (Berger, 2007; Li et al., 2007). This complexity is further compounded by the rapidly expanding number of co-activators/co-repressors identified and the myriad of attendant enzymatic activities delivered to chromatin (Lonard and O'Malley, 2006; Rosenfeld et al., 2006). Finally, detailed kinetic analysis of co-activator/co-repressor occupancy at the promoters revealed a highly dynamic process of cofactor exchange (Fig. 1) (Metivier et al., 2006; Perissi and Rosenfeld, 2005; Rochette-Egly, 2005; Rosenfeld et al., 2006). This review will focus on the dynamics of coactivator recruitment and their role in NR mediated transcription activation.

Figure 1. Dynamic association of cofactors with NR target promoters.

Nuclear receptor (NR) mediated transcription activation is accompanied by dynamic association of chromatin remodeling complexes (CRC), co-activators, Mediator, general transcription factors (GTFs) and the RNA pol II (POL II) machinery with the promoter. These factors are recruited to chromatin via various protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions (blue double arrows ↔). The dynamic exchange of factors on target promoters plays an important role in modulating expression of target genes (grey double arrows↔). The combinatorial action of the NR, co-activators, CRC and the Mediator complex leads to changes in histone modifications (green nucleosomes) and chromatin remodeling/nucleosome loss, leading to robust transcriptional output (black arrow). In addition to these productive cycles of transcription, stochastic interaction of factors with various regions of the genome may occur, but not necessarily leading to productive transcription (grey double arrows↔).

Nuclear receptor mediated transcription

Nuclear receptors are a super-family of ligand responsive transcription factors that regulate target gene expression within chromatin to elicit important biological responses to stimuli. The packing of the genome into chromatin restricts access of various transcription factors such as NRs and the members of the general transcription machinery to promoter regulatory regions (van Holde, 1989; Wolffe, 1998). Therefore, the underlying promoter chromatin structure and modulation of this structure has been shown to be a key aspect of regulating gene expression (Berger, 2007; Li et al., 2007).

Nuclear receptor mediated transcription activation involves recruitment of coactivators by the receptor to the target promoter to modulate the chromatin architecture. These coactivators include the p160/SRC family of proteins that interact directly with NRs through their LXXLL NR box domains (Heery et al., 1997; Perissi and Rosenfeld, 2005). p160/SRC proteins provide a scaffold for further recruitment of coactivators including histone acetyltransferases (HAT), such as p300/CBP and histone methyltransferases (HMTs), for example CARM1 and PRMT1. These enzymes are recruited to covalently modify histones to allow changes in the chromatin architecture as well signal for recruitment of additional coregulatory proteins (Berger, 2007; Kinyamu and Archer, 2004; Kouzarides, 2007; Perissi and Rosenfeld, 2005; Stallcup et al., 2003). In addition to the covalent modifying enzymatic activities, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes, such as SWI/SNF, is recruited to the promoters and work in concert with histone modifying enzymes to alter nucleosome dynamics at the promoter region allowing additional coactivators, Mediator complex, GTFs and the RNAPII machinery access to the promoter chromatin (Aoyagi et al., 2005; Belakavadi and Fondell, 2006; Trotter and Archer, 2007).

A Newtonian, ordered and dynamic recruitment of cofactors

Kinetic chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays analyzing the timing of recruitment of various cofactors after ligand treatment has revealed that cofactors are recruited in a dynamic manner to target promoters in a specific sequential order (Metivier et al., 2006). As an example, ChIP analysis of the ER-α driven pS2 promoter in MCF-7 breast cancer cells following estradiol treatment, with prior α-amanitin synchronization, demonstrated a 20-40min cycle of ordered recruitment of combination of coactivators, changes in chromatin modifications and the recruitment of the transcription machinery which leads to gene expression (Metivier et al., 2003). Additional transcription responses mediated by NRs such as AR, VDR and PR, have also shown dynamic temporal pattern of coactivator recruitment and histone modifications upon transcription activation, indicating that these rapid changes are a common theme that is utilized in regulating the gene expression profiles of NR mediated transcription (Fig. 1) (Aoyagi and Archer, 2007; Kang et al., 2002; Sharma and Fondell, 2002; Vaisanen et al., 2005). Interestingly, analysis of various ER and TR driven promoters show slightly different kinetics by which some of the coactivators are recruited, suggesting that the exact timing of factor recruitment maybe promoter specific, perhaps contributing gene/tissue specific kinetics and magnitude of expression from the same hormone signal (Liu et al., 2006; Shang et al., 2000).

Advances in cell biology have also contributed to our understanding by providing a picture of very rapid fluctuations in protein dynamics within living cells (Belmont, 2001; Misteli, 2007). However, fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching (FRAP) analysis of nuclear protein mobility seems to paint a slightly different picture of NR mobility compared to the kinetic ChIP assay data. Real-time, single cell imaging analysis of NRs showed that the NRs are highly mobile in the nucleus (Hager et al., 2004). This is consistent with prior ideas where receptors would be thought to transiently associate with high affinity binding sites as a prelude to a successful ignition of the transcriptional response (Archer et al., 1991; Rigaud et al., 1991; Yamamoto and Alberts, 1976). By the use of tandem arrays of hormone responsive promoters, NRs such as GR and interacting coactivators have been found to rapidly exchange, in the order of seconds on the target promoter, suggesting that these factors are continuously scanning the promoter in a stochastic fashion termed ‘hit-and-run’ (McNally et al., 2000). The differences in the observations made by ChIP and FRAP experiments are most probably due to the methodology and dependent on the protein population each of these assays actually measure. ChIP detects stable association of factors as well as protein-DNA interactions which occur at the promoter in a population of cells over the duration of the cross-linking step of the ChIP assay, while FRAP detects bulk, rapid and both stable and unstable association of factors with several hundred tandem promoter arrays within a single cell. It is possible that the ChIP assay detects the stable productive association of NRs and coactivators while the FRAP assay detects any association that occurs including those interactions that are transcriptionally productive and non-productive (Hager et al., 2004; Metivier et al., 2006). While one must keep in mind the experimental differences between the two methodologies, it is important to note that regardless of the discrepancy between the ChIP and the FRAP data, both point to the dynamic nature of receptor and cofactor interaction with the promoter that occur during NR mediated transcription and this dynamic interplay between the cofactors and the promoter is a vital part of gene regulation.

While recruitment of receptors and cofactors as measured by kinetic ChIP and FRAP assays occur in the time frame of minutes and seconds, some events such as dephosphorylation of histone H1 occur in the time frame of hours (7-24hrs) upon glucocorticoid treatment which creates a refractory promoter state that is resistant to additional hormone treatment as shown on the mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter. The phosphorylation of H1 returns after the hormone has been removed for 24hrs which renders the promoter responsive to hormone once again (Lee and Archer, 1998). These results indicate that changes in chromatin modifications and kinetics of cofactor association with the promoter occur at overlapping but distinct time frames to fine tune the transcriptional output.

Future Directions

Numerous studies on the interplay of coactivators at promoters for NR mediated gene expression have revealed that coactivator action is not a static process but a highly dynamic one with specific order of recruitment of various combinations of coactivators which regulates the magnitude and kinetics of gene expression. With this appreciation of the kinetics has come the realization that multitude of coactivators, many of which are mega Dalton sized multi-subunit complexes, are being involved in the transcription activation process. This raises the question of how all these factors assemble in three dimensional space that includes the gene regulatory chromatin architecture, which is now thought to extend well beyond the traditional promoter 5' of the gene transcription stat sites (Carroll et al., 2005; Carroll et al., 2006; Kwon et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2007). How the ordered recruitment and exchange of factors within the chromatin substrate occur at the nucleosome, oligonucleosome and higher order chromatin architecture levels will be of great interest.

In addition, dynamic changes in chromatin modifications accompany gene expression (Metivier et al., 2006). The readout of these modifications have been identified for some marks such as lysine acetylated histone binding by bromo-domain containing proteins, binding of lysine methylated histones by chromo, PHD finger and WD-40 domain containing proteins to further influence chromatin architecture and additional cofactor binding (Kouzarides, 2007; Mellor, 2006; Wysocka et al., 2005; Wysocka et al., 2006). It will be important to directly correlate how changes in such histone marks are reflected in the kinetics of coactivator recruitment on the same promoter within a cell by ChIP-reChIP experiments and how removal of such marks are reflected in the disassembly of the coactivator and recruitment of additional factors at the promoter. Also, with new co-regulatory factors being discovered on a frequent basis, it will be critical to determine where some of the newly identified coactivators such as the histone demethylase JHDM2A which has been found to be recruited to AR target genes that results in histone H3K9 demethylation and transcription activation, fit in the ordered kinetic recruitment of coactivators (Yamane et al., 2006).

The dynamic and combinatorial nature of co-activator/co-repressor recruitment is likely to be highly promoter, cell and tissue specific, leading to varying gene and cellular response to the same biological signal as seen with hormones (Larsen et al., 2003). Many chromatin modifying machines have also been shown to be modifiers of proteins other than histones. Their targets include NRs, and various other coactivators such as SRC3 (AIB1) and p300/CBP, where changes in post-translational modifications play a role in regulating the activities of these factors (Black et al., 2006; Chen et al., 1999; Faus and Haendler, 2006; Li and Shang, 2007; Popov et al., 2007; Rosenfeld et al., 2006). Therefore, in addition to the timing of coactivator recruitment, the regulation of the post-translational modifications that modulate the activities of these factors and how that may influence the kinetics of factor recruitment and release from the promoter, must also be taken into account and added to the already complex landscape of gene activation. The ChIP and FRAP experiments have been conducted so far in a population of cells or on hundreds of tandem arrays of promoters in a single cell, respectively. In the future, with improved technologies and methodologies, it will be possible to perform a kinetic analysis of cofactor recruitment on a single promoter within a single cell to determine precisely what transpires upon transcription activation, permitting direct comparisons of mechanism(s) of transcription of different genes from the same hormonal signal. This new class of information will be of vital interest and critical in development hormone based therapies to manipulate the transcriptional and cellular response of disease causing genes in target cells.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, and NIEHS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aoyagi S, Archer TK. Dynamic histone acetylation/deacetylation with progesterone receptor-mediated transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:843–56. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi S, Trotter KW, Archer TK. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes and their role in nuclear receptor-dependent transcription in vivo. Vitam Horm. 2005;70:281–307. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)70009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer TK, Cordingley MG, Wolford RG, Hager GL. Transcription factor access is mediated by accurately positioned nucleosomes on the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:688–98. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belakavadi M, Fondell JD. Role of the mediator complex in nuclear hormone receptor signaling. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;156:23–43. doi: 10.1007/s10254-005-0002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont AS. Visualizing chromosome dynamics with GFP. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:250–7. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–12. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JC, Choi JE, Lombardo SR, Carey M. A mechanism for coordinating chromatin modification and preinitiation complex assembly. Mol Cell. 2006;23:809–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, Fox EA, Silver PA, Brown M. Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell. 2005;122:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger TR, Eeckhoute J, Brodsky AS, Keeton EK, Fertuck KC, Hall GF, Wang Q, Bekiranov S, Sementchenko V, Fox EA, Silver PA, Gingeras TR, Liu XS, Brown M. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1289–97. doi: 10.1038/ng1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lin RJ, Xie W, Wilpitz D, Evans RM. Regulation of hormone-induced histone hyperacetylation and gene activation via acetylation of an acetylase. Cell. 1999;98:675–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faus H, Haendler B. Post-translational modifications of steroid receptors. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:520–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager GL, Nagaich AK, Johnson TA, Walker DA, John S. Dynamics of nuclear receptor movement and transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S, Parker MG. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 1997;387:733–6. doi: 10.1038/42750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Pirskanen A, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. Involvement of proteasome in the dynamic assembly of the androgen receptor transcription complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48366–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyamu HK, Archer TK. Modifying chromatin to permit steroid hormone receptor-dependent transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YS, Garcia-Bassets I, Hutt KR, Cheng CS, Jin M, Liu D, Benner C, Wang D, Ye Z, Bibikova M, Fan JB, Duan L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD. Sensitive ChIP-DSL technology reveals an extensive estrogen receptor alpha-binding program on human gene promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4852–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700715104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Saunders; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee HL, Archer TK. Prolonged glucocorticoid exposure dephosphorylates histone H1 and inactivates the MMTV promoter. Embo J. 1998;17:1454–66. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Shang Y. Regulation of SRC family coactivators by post-translational modifications. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1101–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Vega VB, Thomsen JS, Zhang T, Kong SL, Xie M, Chiu KP, Lipovich L, Barnett DH, Stossi F, Yeo A, George J, Kuznetsov VA, Lee YK, Charn TH, Palanisamy N, Miller LD, Cheung E, Katzenellenbogen BS, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Wei CL, Liu ET. Whole-Genome Cartography of Estrogen Receptor alpha Binding Sites. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e87. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xia X, Fondell JD, Yen PM. Thyroid hormone-regulated target genes have distinct patterns of coactivator recruitment and histone acetylation. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:483–90. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell. 2006;125:411–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally JG, Muller WG, Walker D, Wolford R, Hager GL. The glucocorticoid receptor: rapid exchange with regulatory sites in living cells. Science. 2000;287:1262–5. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor J. It takes a PHD to read the histone code. Cell. 2006;126:22–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Penot G, Hubner MR, Reid G, Brand H, Kos M, Gannon F. Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell. 2003;115:751–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Reid G, Gannon F. Transcription in four dimensions: nuclear receptor-directed initiation of gene expression. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:161–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T. Beyond the sequence: cellular organization of genome function. Cell. 2007;128:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Rosenfeld MG. Controlling nuclear receptors: the circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:542–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov VM, Wang C, Shirley LA, Rosenberg A, Li S, Nevalainen M, Fu M, Pestell RG. The functional significance of nuclear receptor acetylation. Steroids. 2007;72:221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud G, Roux J, Pictet R, Grange T. In vivo footprinting of rat TAT gene: dynamic interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and a liver-specific factor. Cell. 1991;67:977–86. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90370-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochette-Egly C. Dynamic combinatorial networks in nuclear receptor-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32565–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK. Sensors and signals: a coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal-dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1405–28. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103:843–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Fondell JD. Ordered recruitment of histone acetyltransferases and the TRAP/Mediator complex to thyroid hormone-responsive promoters in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7934–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122004799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallcup MR, Kim JH, Teyssier C, Lee YH, Ma H, Chen D. The roles of protein-protein interactions and protein methylation in transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors and their coactivators. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;85:139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter KW, Archer TK. Nuclear receptors and chromatin remodeling machinery. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;265-266:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:451–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisanen S, Dunlop TW, Sinkkonen L, Frank C, Carlberg C. Spatio-temporal activation of chromatin on the human CYP24 gene promoter in the presence of 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Holde KE. Chromatin. Springer Verlag; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe AP. Chromatin structure and function. Academic Press; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka J, Swigut T, Milne TA, Dou Y, Zhang X, Burlingame AL, Roeder RG, Brivanlou AH, Allis CD. WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development. Cell. 2005;121:859–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocka J, Swigut T, Xiao H, Milne TA, Kwon SY, Landry J, Kauer M, Tackett AJ, Chait BT, Badenhorst P, Wu C, Allis CD. A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature. 2006;442:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature04815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto KR, Alberts BM. Steroid receptors: elements for modulation of eukaryotic transcription. Annu Rev Biochem. 1976;45:721–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.45.070176.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane K, Toumazou C, Tsukada Y, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wong J, Zhang Y. JHDM2A, a JmjC-containing H3K9 demethylase, facilitates transcription activation by androgen receptor. Cell. 2006;125:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]