Abstract

We describe the functional consequences of mutations in the linker between the second and third transmembrane segments (M2–M3L) of muscle acetylcholine receptors at the single-channel level. Hydrophobic mutations (Ile, Cys, and Phe) placed near the middle of the linker of the α subunit (αS269) prolong apparent openings elicited by low concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh), whereas hydrophilic mutations (Asp, Lys, and Gln) are without effect. Because the gating kinetics of the αS269I receptor (a congenital myasthenic syndrome mutant) in the presence of ACh are too fast, choline was used as the agonist. This revealed an ∼92-fold increased gating equilibrium constant, which is consistent with an ∼10-fold decreased EC50 in the presence of ACh. With choline, this mutation accelerates channel opening ∼28-fold, slows channel closing ∼3-fold, but does not affect agonist binding to the closed state. These ratios suggest that, with ACh, αS269I acetylcholine receptors open at a rate of ∼1.4 × 106 s−1 and close at a rate of ∼760 s−1. These gating rate constants, together with the measured duration of apparent openings at low ACh concentrations, further suggest that ACh dissociates from the diliganded open receptor at a rate of ∼140 s−1. Ile mutations at positions flanking αS269 impair, rather than enhance, channel gating. Inserting or deleting one residue from this linker in the α subunit increased and decreased, respectively, the apparent open time approximately twofold. Contrary to the αS269I mutation, Ile mutations at equivalent positions of the β, ε, and δ subunits do not affect apparent open-channel lifetimes. However, in β and ε, shifting the mutation one residue to the NH2-terminal end enhances channel gating. The overall results indicate that this linker is a control element whose hydrophobicity determines channel gating in a position- and subunit-dependent manner. Characterization of the transition state of the gating reaction suggests that during channel opening the M2–M3L of the α subunit moves before the corresponding linkers of the β and ε subunits.

Keywords: nicotinic receptors, allosteric proteins, single-channel kinetics, transition state

INTRODUCTION

The muscle acetylcholine receptor channel (AChR) is a ligand-activated ion channel that mediates neuromuscular transmission in vertebrates (reviewed in Edmonds et al. 1995). The adult form of the channel consists of five subunits (α2βδε), each having four putative membrane-spanning domains (M1, M2, M3, and M4; reviewed in Karlin and Akabas 1995). This topology is shared by all members of the superfamily of pentameric nicotinoid receptors, which includes muscle and neuronal nicotinic, 5-HT3, glycine, GABAA, and GABAC receptors (Ortells and Lunt 1995).

The second transmembrane segment (M2) from each subunit lines the narrow region of the ion-permeation pathway and is critical for both ion permeation (Imoto et al. 1988; Villarroel et al. 1991; Cohen et al. 1992) and gating (Filatov and White 1995; Labarca et al. 1995; Ohno et al. 1995; Chen and Auerbach 1998; Grosman and Auerbach 2000a,Grosman and Auerbach 2000b) of the channel. The intracellular projection of M2 (i.e., the linker between the first and second transmembrane segments) has been shown to contribute to the charge selectivity filter of α7 AChRs (Galzi et al. 1992; Corringer, et al. 1999). The extracellular projection of M2 (i.e., the linker between the second and third transmembrane segments, M2–M3L) has been mainly implicated with gating in α3, α7, and β4 subunit-containing AChRs (Campos-Caro et al. 1996; Rovira et al. 1998, Rovira et al. 1999), glycine receptor α1 homomers (Lynch et al. 1997), and GABAC receptor ρ1 homomers (Kusama et al. 1994).

The effect of naturally occurring mutations in the M2–M3L also suggests a role in channel gating. The slow-channel congenital myasthenic syndrome (SCCMS) mutation αS269I prolongs the AChR's apparent open time (Croxen et al. 1997), and the hyperekplexia mutations R271L, R271Q, K276E, and Y279C, in the α1 subunit of the glycine receptor, shorten the apparent open time (Lynch et al. 1997 and references therein; Lewis et al. 1998.). In addition, the extracellular location of the M2–M3L makes it a likely target of drugs and synaptically released agents. Indeed, residues within or flanking this loop have been shown to be critical for the modulatory effects of Zn2+ in GABAA receptors (Fisher and Macdonald 1998), and of ethanol and volatile anesthetics in GABAA and glycine receptors (Mihic et al. 1997).

To characterize the M2–M3L of the muscle AChR, we engineered a set of mutations in this region of the different subunits of adult mouse receptors and studied their effects on the kinetics of activation of single AChRs. Our results indicate that M2–M3L mutations affect activation by selectively altering channel gating. Furthermore, the results suggest that during channel opening the M2–M3L of the α subunit moves before the corresponding linkers of the β and ε subunits.

METHODS

Mutagenesis and Expression

Mouse cDNA clones were obtained as described by Grosman and Auerbach 2000a,Grosman and Auerbach 2000b. The α-subunit clone contained an incidental M4 mutation (V433A) that has no functional consequences (Salamone et al. 1999). Mutations were engineered using either the QuickChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) protocol or the cassette mutagenesis method (Sine 1993). All mutations were confirmed by restriction mapping and dideoxy sequencing. HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected by calcium-phosphate precipitation (Ausubel et al. 1992; Salamone et al. 1999). The medium was changed ∼24 h after addition of the calcium-phosphate precipitate, and electrophysiological recordings started ∼24 h later.

Patch-Clamp Recordings and Analysis

Recordings were performed in the cell-attached patch configuration (Hamill et al. 1981) at ∼22°C. The pipette solution contained (mM): 142 KCl, 5.4 NaCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.7 MgCl2, 10 HEPES/KOH, pH 7.4. In most experiments using ACh, the bath solution was the same as the pipette solution. In all other experiments, the bath solution was Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (mM): 137 NaCl, 0.9 CaCl2, 2.7 KCl, 1.5 KH2PO4, 0.5 MgCl2, and 8.1 Na2HPO4, pH 7.3. Single-channel currents were amplified using a patch-clamp amplifier (PC-505; Warner Instrument Corp. or 200B; Axon Instruments, Inc.) and were digitized at 100 kHz.

To separate the more rapid binding and gating steps from the slower desensitization steps, clusters of single-channel activity were identified and used to estimate open probability (P open), time constants, and gating rate constants. Clusters were defined as a series of openings separated by closures shorter than a critical time, τc (Sakmann et al. 1980). In the presence of ACh or low concentrations of choline, τc was determined as described by Salamone et al. 1999. In the case of currents elicited with saturating choline, τc was the longest time interval that defined clusters still best fitted with a C ↔ O kinetic model, as described by Grosman and Auerbach 2000b. Clusters of raw data were idealized according to either a half-amplitude threshold-crossing criterion (program IPROC; Sachs et al. 1982) at a bandwidth of ∼4 kHz or a hidden-Markov-model–based algorithm (program SKM) at a bandwidth of ∼18 kHz. Only clusters whose overall mean open time was within ±2 SD of the mean of the corresponding patch were retained for further analysis (typically >98% of the original data; programs LPROC or SELECT).

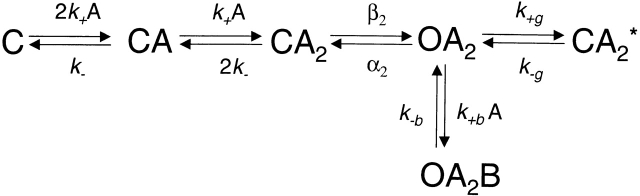

Equilibrium concentration–response curves were analyzed in the framework of Fig. 1:

Scheme S1.

where C and O denote the closed and open channel, respectively, A denotes the agonist, OA2B represents the open channel blocked by the agonist itself, and CA2* is a shut state whose mean lifetime is independent of the agonist concentration (Salamone et al. 1999). In the presence of acetylcholine (ACh), the latter has a mean duration of ∼1 ms and is therefore distinct from the long-lived desensitized state(s) that gives rise to the longer-lived closed intervals between clusters. P open values were estimated from the idealized current traces as the fraction of time the channel is open within a cluster. Plots of P open vs. agonist concentration were fitted with to estimate the microscopic agonist-dissociation equilibrium constant (K d = k −/k +) and the diliganded-gating equilibrium constant (θ2 = β2/α2):

|

1 |

where c = K B/(A + K B) and K B is the dissociation equilibrium constant for channel block (k −b/k +b; 2 mM for ACh and 20 mM for choline), and K g is the equilibrium constant between OA 2 and CA 2* (k +g/k −g; 0.05 for ACh, as in Salamone et al. (1999), and ignored in the presence of choline). corresponds to the classical sequential model (del Castillo and Katz 1957; Magleby and Stevens 1972) modified for the case of two equivalent binding sites, fast blockade by the agonist, and a short-lived desensitized state (Salamone et al. 1999).

The opening rate constants of the various constructs in the presence of ACh were estimated by fitting plots of β′ vs. agonist concentration (A) with the following empirical equation (Hill equation, ):

|

2 |

where β′ (the “effective” opening rate) is defined as the reciprocal of the slowest component of the closed-time distribution, β2 is the opening rate constant, A 50 is the agonist concentration at which β′ is half maximal (i.e., β2/2), and n is the Hill coefficient. β′ at each ACh concentration was estimated from the fit of log-binned (Sigworth and Sine 1987) closed-time histograms with sums of exponential densities. Likewise, mean open times in the presence of ACh were estimated from the exponential fit of log-binned open-time histograms. Both closed- and open-interval histograms were compiled from data idealized (half-amplitude criterion) at an effective bandwidth of 4 kHz. The opening and closing rate constants in the presence of saturating 20 mM choline were estimated, after idealization (program SKM), by applying a full-likelihood algorithm that includes a correction for missed events (program MIL; Qin et al. 1996, Qin et al. 1997). We used a one-step C ↔O kinetic scheme, an effective bandwidth of ∼18 kHz, and a dead time of ∼25 μs, as described by Grosman and Auerbach 2000a,Grosman and Auerbach 2000b. Because of the lengthening effect of fast blockade by choline on the duration of openings, the closing rate constants determined in this way are underestimations by a factor no greater than 2 (Grosman and Auerbach 2000b). As the single-channel current amplitude was reduced to similar extents in both wild-type and mutants (i.e., the affinity for choline as a blocker is largely unaffected by the mutations), the prolongation of the openings is expected to be the same for all tested constructs.

The distribution of open times in the presence of low concentrations of ACh was analyzed in the context of an MWC-like kinetic model (Scheme II; Monod et al. 1965). This model incorporates the dissociation of agonist from the open channel as well as openings of un- and mono-liganded receptors.

Where k −/k + (= K d) and j −/j + (= J d) are the microscopic agonist-dissociation equilibrium constants from the closed and open channels, respectively, β0/α0 (= θ0), β1/α1 (= θ1), and β2/α2 (= θ2) are the gating equilibrium constants of un-, mono-, and diliganded receptors, respectively, k +D/k −D is the desensitization equilibrium constant, and k +g/k −g is the equilibrium constant between OA 2 and CA 2*. Because this model was used to interpret data recorded at low concentrations of ACh, blockade by the agonist itself was ignored. According to Fig. 2, to satisfy detailed balance, θ1 = θ0 K d/J d and θ2 = θ0(K d/J d)2.

Scheme S2.

Single-channel analysis programs of the QuB suite are available at www.qub.buffalo.edu.

RESULTS

The SCCMS Mutation αS5I

The M2–M3 linkers of the different subunits of muscle, neuronal, and Torpedo electroplaque AChRs are all 15 amino acids long and contain several conserved residues, including two Pro (Table ). The homology between aligned residues is largely lost, however, when the anion-selective members of the superfamily of nicotinoid receptors (GABA and glycine receptors) are included in the comparison, although the first Pro is still present.

Table 1.

M2–M3 Linker-sequence Alignment of the Members of the Superfamily of Nicotinoid Receptors

| Subunit | −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/hAChRα | E | L | I | P | S | T | S | S | A | V | P | L | I | G | K |

| tAChRα | E | L | I | P | S | T | S | S | A | V | P | L | I | G | K |

| m/hAChRβ | D | K | V | P | E | T | S | L | A/S | V | P | I | I | I | K |

| tAChRβ | D | K | V | P | E | T | S | L | S | V | P | I | I | I | R |

| m/hAChRδ | K | R | L | P | A | T | S | M | A | I | P | L | V/I | G | K |

| tAChRδ | Q | R | L | P | E | T | A | L | A | V | P | L | I | G | K |

| m/hAChRγ | K | K | V | P | E | T | S | Q | A | V | P | L | I | S | K |

| tAChRγ | Q | K | V | P | E | T | S | L | N | V | P | L | I | G | K |

| m/hAChRε | Q | K | I | P | E | T | S | L | S | V | P | L | L | G | R |

| hAChRα2 | E | I | I | P | S | T | S | L | V | I | P | L | I | G | E |

| hAChRα3 | E | T | I | P | S | T | S | L | V | I | P | L | I | G | E |

| hAChRα4 | E | I | I | P | S | T | S | L | V | I | P | L | I | G | E |

| hAChRα5 | E | I | I | P | S | S | S | K | V | I | P | L | I | G | E |

| hAChRα6 | E | T | I | P | S | T | S | L | V | V | P | L | V | G | E |

| hAChRα7 | E | I | M | P | A | T | S | D | S | V | P | L | I | A | Q |

| chAChRα8 | E | I | M | P | A | T | S | D | S | V | P | L | I | A | Q |

| hAChRα9 | E | I | M | P | A | S | — | E | N | V | P | L | I | G | K |

| hAChRβ2 | K | I | V | P | P | T | S | L | D | V | P | L | V | G | K |

| hAChRβ3 | E | I | I | P | S | S | S | K | V | I | P | L | I | G | E |

| hAChRβ4 | K | I | V | P | P | T | S | L | D | V | P | L | I | G | K |

| h5-HT3A | D | T | L | P | A | T | A | I | G | T | P | L | I | G | V |

| h5-HT3B | N | Q | V | P | R | S | V | G | S | T | P | L | I | G | H |

| m/hGlyRα1–4 | A | S | L | P | K | V | S | Y | V | K | A | I | D | I | W |

| hGlyRβ | A | E | L | P | K | V | S | Y | V | K | A | L | D | V | W |

| hGABAAα1–6 | N/H | S | L | P | K | V | A/S | Y | A/L | T | A | M | D | W | F |

| hGABAAβ1–3 | E | T | L | P | K | I | P | Y | V | K | A | I | D | I/M | Y |

| r/hGABAAγ1–3 | K | S | L | P | K/R | V | S | Y | V | T | A | M | D | L | F |

| hGABAAδ | S | S | L | P | R | A | S | A | I | K | A | L | D | V | Y |

| hGABAAε | K | N | F | P | R | V | S | Y | I | T | A | L | D | F | Y |

| hGABAAπ | T | S | L | P | N | T | N | C | F | I | K | A | I | D | V |

| hGABACρ1–2 | A | S | M | P | R | V | S | Y | I-V | K | A | V | D | I | Y |

Position −2 marks the putative beginning of the M2–M3 linker for ACh and serotonin (5-HT3) receptors. In glycine and GABA receptors, this domain presumably starts one residue before (position –3) being an R in GlyRα1–4 and all GABAA receptor subunits, an A in the GlyRβ subunit, and an N in both GABACρ subunits. A Pro residue occupies the fourth or fifth position in all members of the superfamily and is assigned the number 1, according to our numbering system. The putative end of this linker is at position 12 in Ach, 6 in 5-HT3, 10 in glycine, and 7–8 in GABA receptors. The sequences and putative topology of all subunits were taken from the SWISS-PROT Protein Sequence Database, with the exception of AChR α8 (Schoepfer et al. 1990), 5-HT3A, and 5-HT3B (Davies et al. 1999). Whenever available, the human (h) sequences are given; otherwise, the sequences of either chicken (ch), mouse (m), or rat (r) are indicated. The M2–M3 linker sequences of the human α, β, δ, and ε AChR subunits are almost identical to those of mouse (the clones used in this paper). Torpedo (t) sequences are also included.

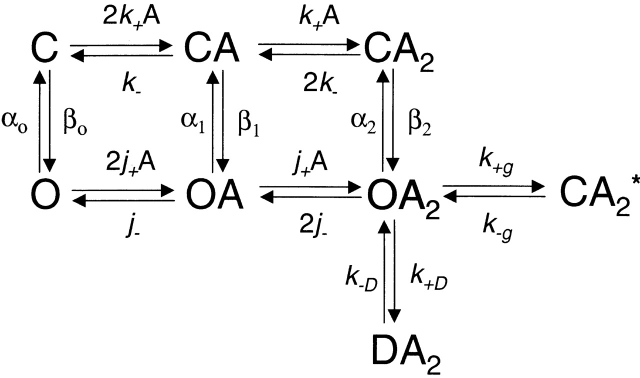

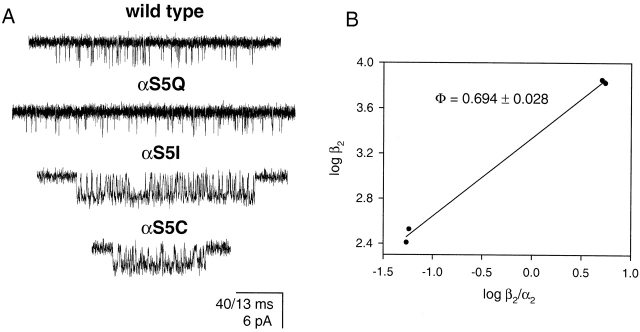

The naturally occurring mutation αS269I (position 5 in our numbering system; αS5I) causes a congenital myasthenic syndrome (Croxen et al. 1997). Example single-channel currents from recombinant mouse αS5I AChRs in the presence of 0.2 μM ACh are shown in Fig. 1. The open-interval duration histogram (−70 mV; 4 kHz) was best fitted with two exponential components, the mean of the slowest being ∼4.5 ms. In the wild type, under otherwise identical experimental conditions, the mean of the slowest (and predominant) component was ∼0.75 ms (Table ).

Figure 1.

Open-interval properties of wild-type (WT) and αS5 mutant AChRs. Currents were recorded in the presence of 0.2 (αS5I, αS5C, and αS5F) or 1 (all other constructs) μM ACh. (A) The slowest open-time constant of each construct is indicated as the mean ± SD of three to six patches. (B) Example open-interval histograms, superimposed density functions, and single-channel currents. Histograms were best fitted with two (αS5I, αS5C, and αS5F) or one (all other constructs) exponential component. No correction for missed events was made. Pipette potential ≅ +70 mV. Analysis and display f c ≅ 4 kHz. Openings are downward deflections.

Table 2.

Experimental τo Values of M2–M3L Mutant AChRs Activated by ACh

| Mutant | τo | SD | Mutant | τo | SD | Mutant | τo | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ms | ms | ms | ||||||

| Wild type | 0.75 | 0.21 | αS5K | 0.84 | 0.03 | βL5I | 0.56 | 0.11 |

| ADD | 1.46 | 0.05 | αS5Q | 0.60 | 0.10 | εS4I | 6.60 | 0.90 |

| DEL | 0.28 | 0.05 | αS5I | 4.50 | 0.30 | εL5S | 1.20 | 0.20 |

| αT3A | 0.16 | 0.04 | αS5C | 7.50 | 0.30 | δT3I | 0.51 | 0.06 |

| αT3I | 0.17 | 0.03 | αS5F | 7.40 | 0.80 | δS4I | 0.65 | 0.05 |

| αS4A | 1.20 | 0.20 | αA6S | 0.71 | 0.05 | δM5S | 0.68 | 0.07 |

| αS4I | 0.36 | 0.03 | αV7A | 0.74 | 0.04 | δM5I | 0.94 | 0.15 |

| αS5A | 0.79 | 0.08 | βS4I | 9.10 | 0.90 | δA6I | 1.01 | 0.14 |

| αS5D | 0.61 | 0.06 | βL5S | 1.02 | 0.02 |

At an effective bandwidth of ∼4 kHz, the minimum detectable time using the “half-amplitude” idealization criterion is ∼45 μs (Colquhoun and Sigworth 1995) and, therefore, in wild-type AChRs, only ∼1% of the brief sojourns in the diliganded closed state (∼10 μs on average) are detected. As a consequence, apparent open intervals often include two or more consecutive openings and, therefore, are not true estimates of the reciprocal of the diliganded closing rate constant. Taking the sequential model (Fig. 1) as an approximation of the channel's kinetic behavior, and neglecting the (short) time spent in the closed diliganded state (CA 2), the mean duration of the slowest component of these apparent openings is given by:

|

3 |

where (1 + β2/2k −) is the mean number of openings per burst. In the experiments at low concentrations of ACh, the probability that sojourns in shut states other than CA 2 were shorter than the time resolution of 45 μs (and thus that were included within an apparent opening) is negligible. Likewise, the probability that a sojourn in CA 2 was longer than 45 μs (and thus that terminates an apparent opening) is vanishingly small. In conclusion, an “apparent opening,” defined as a series of openings separated by closures shorter than 45 μs, is likely to reflect a sojourn in the combined set of states (CA 2 + OA 2).

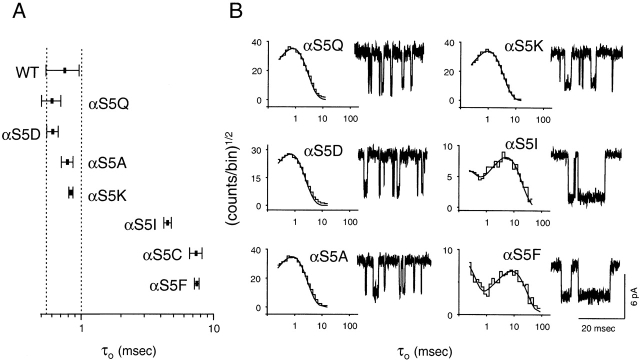

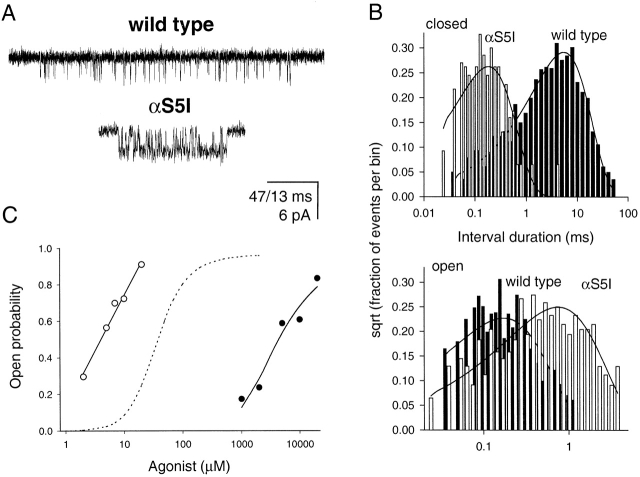

From , it can be seen that the prolonged open-time constant of αS5I AChRs may arise from one or a combination of the following: an increased opening rate constant (β2), a decreased closing rate constant (α2), or a decreased agonist-dissociation rate constant (2k −). To distinguish between these possibilities, we studied the effect of the αS5I mutation on gating by using choline as the agonist. Choline slows channel gating so open and closed intervals can be fully resolved (Grosman and Auerbach 2000b). Fig. 2 shows clusters of single-channel currents of αS5I AChRs recorded in saturating 20-mM choline. The opening rate constant (β2) was 7,098 ± 1,227 s−1, and the closing rate constant (α2) was 1,487 ± 313 s−1. These are, respectively, 27.7× faster and 3.33× slower than those of wild-type AChRs activated by choline (Grosman and Auerbach 2000b). Thus, with choline as the agonist, the αS5I mutation increases the gating equilibrium constant ∼92-fold, mostly due to an increase in β2.

Figure 2.

Single-channel properties of wild-type and αS5I AChRs. (A) Single-channel clusters in the presence of 20-mM choline. Display f c ≅ 6 kHz. Openings are downwards. Calibration bar: 47 ms for wild-type and 13 ms for αS5I receptors. (B) Monoexponential dwell-time histograms and superimposed density functions of currents elicited by 20-mM choline. Analysis f c = 18 kHz. The αS5I mutation speeds up channel opening more than it slows down channel closing. (C) Equilibrium concentration–response curves of αS5I receptors in the presence of ACh (○) or choline (•). The former was fitted with a straight line; the latter was fitted with . The dashed line corresponds to the dose–response curve expected from the wild-type channel in the presence of ACh.

Next, we sought to determine whether the αS5I mutation affects binding affinity. Single-channel currents elicited over a range of choline concentrations were recorded, and intracluster P open values were estimated and compared with that of ACh (Fig. 2). The lower efficacy (i.e., smaller θ2) of choline allowed us to fit the P open-vs.-concentration data with , yielding θ2 = β2/α2 = 2.5 ± 0.9 and K d = k −/k + = 3.3 ± 1.4 mM. This value of θ2 is consistent with the rate constants obtained by single-channel kinetic modeling of currents elicited by 20-mM choline with a K B of 20 mM and assuming a sequential model for channel block. The K d for wild-type AChRs activated by choline is not known with certainty because the extremely low efficacy of this agonist makes this dose–response curve difficult to measure. However, the wild-type K d is in the millimolar range (Zhou et al. 1999). Thus, the choline dose–response results suggest that the αS5I mutation does not substantially alter the affinity of the closed-channel transmitter binding site for choline, but rather predominantly affects channel gating.

The gating (θ2) and agonist dissociation (K d) equilibrium constants of ACh-activated receptors could not be directly estimated from the dose–response data (by fitting ) because of the high ACh θ2 value. However, the P open-vs.-concentration relationship of the αS5I mutant activated by ACh revealed an EC50 of ∼4.0 μM, which is ∼10× lower than that of the wild type determined under identical conditions (Salamone et al. 1999). According to , when the gating equilibrium constant is large θ2≫1,EC50≅K dθ2.Therefore, the ∼10-fold decrease in ACh EC50 can be accounted for by an ∼100-fold increase in θ2, which is similar to the 92-fold increase in θ2 measured in the presence of choline. These results indicate that θ2 is increased to the same extent in the presence of ACh or choline. An increase in θ2 can arise from an increase in the unliganded gating equilibrium constant, θ0 (β0/α0) and/or an increase in the closed/open agonist-affinity ratio, K d/J d (Fig. 2). The agonist-insensitive effect of the αS5I mutation on θ2 suggests that this mutation increases the unliganded gating equilibrium constant with little, if any, effect on the affinity ratio, which is expected to be sensitive to the nature of the agonist. Several SCCMS mutations, including αS5I, have been shown to increase unliganded gating, thus turning choline, a normally inert molecule, into a significant agonist (Zhou et al. 1999).

Although gating of αS5I receptors in the presence of ACh is exceedingly fast for the rate constants to be measured directly, the closing and opening rate constants can be predicted based on the results in the presence of choline. This is because the structure of the AChR at the transition state of the gating reaction is likely to be the same regardless of the particular ligand bound (Grosman et al. 2000). Thus, like in the presence of choline, we estimate that ACh-bound αS5I receptors open ∼27.7× faster, and close ∼3.33× slower, than the wild type; i.e., β2 ≅ 1.4 106 s−1 and α2 ≅ 750 s−1.

Even though the predicted value of β2 cannot be confirmed experimentally from the duration of shut intervals, the effect that such a fast opening rate constant would have on the apparent open-time distribution can be calculated. In particular, we focused on the time constant of the slowest component of the distribution (τo), which, for Fig. 1, is approximately given by at any concentration of agonist. According to this equation, τo for the αS5I mutant should be 48 ms, which is more than 10× longer than the observed τo of ∼4.5 ms.

However, as β2 increases and α2 decreases, the sequential-model simplification (Fig. 1 and ) becomes inappropriate because the probability that a burst of openings terminates from the open state (i.e., by agonist dissociation from the open state followed by closing or by directly entering a desensitized state) is no longer negligible. Accordingly, an MWC-like kinetic model (Monod et al. 1965; Fig. 2) was used to interpret τo values. Considering Fig. 2, it can be shown that τo (the slowest component of the open-time distribution) is an increasing function of agonist concentration whose value at infinite agonist concentration is given by , and at zero agonist concentration (our conditions, approximately) by :

|

4 |

where σ is the sum of all the rate constants leading away from OA 2 other than α2. These are the dissociation rate constant from the diliganded open channel (2j −), the rate constant leading to the long-lived desensitized state (k +D), and the rate constant leading to CA 2* (k +g).

Using the wild-type value of 40,000 s−1 for 2k − (Akk and Auerbach 1996; Wang et al. 1997; Salamone et al. 1999), it can be calculated from that a σ value of 200 s−1 accounts for all three experimental observations in the presence of ACh: (a) a τo value of 0.75 ms for the wild type; (b) a τo value of 4.5 ms for the mutant at low ACh concentration, and (c) an ∼10-fold smaller EC50 for the mutant. We were unable to find other combinations of β2, α2, 2k −, and σ values that could account simultaneously for these three findings.

Mutational Analysis of Position α5

The αS5I mutation increases both the hydrophobicity and size of the side chain. To further characterize the structure–function relationships of this position, we engineered a series of polar and hydrophobic side chains at α5 (Fig. 1 and Table ). Using ACh as the agonist, hydrophobic substitutions (Phe, Cys) increased τo nearly 10-fold, while polar substitutions (Asp, Gln, and Lys) were without effect. Ala, which has the highest mutational probability with Ser, also yielded wild-type-like τo values.

Some of these αS5 mutants were also studied using choline as the agonist (Fig. 3 A). The αS5C mutation had essentially the same effect as the αS5I mutation; that is, it produced a large increase in the opening rate constant (26-fold) and a modest decrease in the closing rate constant (3.7-fold). The αS5Q mutant was similar to the wild type, with essentially no change in the opening (∼1.3-fold increase) or closing (∼1.2-fold increase) rate constants. For both mutations, τo values were calculated using with 2k − = 40,000 s−1 and σ = 200 s−1, assuming that only β2 and α2 change upon mutation. For αS5C and αS5Q receptors, the calculated values were ∼4.5 and 0.77 ms, respectively, in reasonable agreement with the experimental values of 7.5 and 0.6 ms (Table ).

Figure 3.

Transition-state mapping at position α5. (A) Single-channel currents of wild-type and αS5 mutant AChRs in the presence of 20-mM choline. Display f c ≅ 6 kHz. Openings are downwards. Calibration bar: 40 ms for wild-type and αS5Q, and 13 ms for αS5I and αS5C. (B) Brønsted plot of the four constructs. The slope, Φ, is 0.694 ± 0.028.

The similarity of the effects of S/Q and C/I residues suggests that the volume of the α5 sidechain (∼89 and ∼144 Å3 for S and Q, and ∼109 and ∼167 Å3 for C and I, respectively; Zamyatnin 1972) is not a significant factor with regard to channel gating. The overall results suggest that a hydrophobic residue in position α5 increases the AChR gating equilibrium constant.

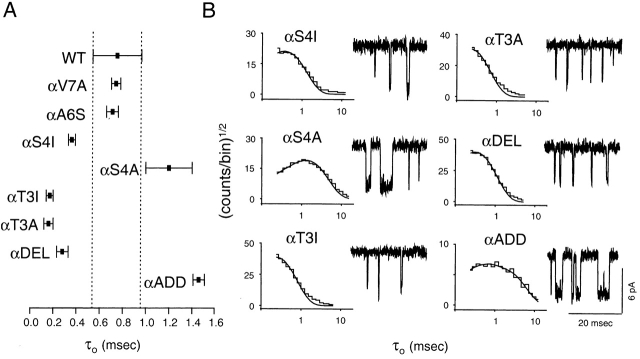

Mutational Analysis of the α-subunit M2–M3L Domain

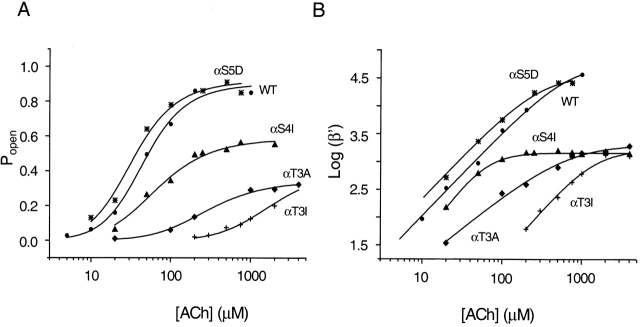

To further explore the role of the M2–M3L in gating, we made additional mutations at different positions of the α subunit (Fig. 4 and Table ). Both T → A and T → I mutations at position α3 shortened τo of ACh-gated currents by a factor of ∼4.5 (0.16–0.17 vs. 0.75 ms in the wild type). For these mutations, kinetic modeling of single-channel clusters elicited by ACh was possible because the opening rate constant was slower than the wild type's and, therefore, the use of choline was not needed. β2 was reduced from ∼50,000 s−1 in the wild type to 2,127 s−1 and 1,730 s−1 in the Ala and Ile mutants (Fig. 5), whereas α2 increased from 2,500 s−1 in the wild type to ∼6,000 s−1 in both mutants. Thus, the consequences of these αT3 mutations are nearly opposite to those of the αS5I mutation; i.e., β2 decreases ∼26-fold and α2 increases ∼2.4-fold. The net effect of these mutations is to decrease θ2 by ∼62-fold. Returning to , the shorter τo in αT3A and αT3I AChRs mainly reflects a reduced number of openings per burst (because of a much smaller β2). Like mutations at position α5, mutations of α3 residues also had a larger effect on channel opening than on channel closing.

Figure 4.

Open-interval properties of α-subunit M2–M3L mutants in positions other than α5. Currents were recorded in the presence of 5 (αT3A and αT3I) or 1 (all other constructs) μM ACh. (A) The slowest open-time constant of each construct is indicated as the mean ± SD of two (αV7A, αS4I, and αADD) or three (all other constructs) patches. (B) Example open-interval histograms, superimposed density functions, and single-channel currents. Histograms were best fitted with one exponential component. No correction for missed events was made. Pipette potential ≅ +70 mV. Analysis and display f c ≅ 4 kHz. Openings are downwards.

Figure 5.

Equilibrium concentration–response curves for wild-type and representative M2–M3L mutant AChRs in the presence of ACh. (A) Intracluster P open as a function of ACh concentration was fitted with . (B) The effective opening rate (β′) as a function of ACh concentration was fitted with . (•) wild type, (*) αS5D, (▴) αS4I, (♦) αT3A, (+) αT3I.

The dose–response properties of αT3I and αT3A activated by ACh are shown in Fig. 5. The K d values of these two mutants for ACh were similar to that of the wild type, while the θ2 values were smaller. This result is consistent with the suggestion that the nearby mutation αS5I does not alter the K d. Together, these results suggest that the M2–M3L of the α subunit is not an important determinant of agonist affinity.

We next studied the effect of S → A and S → I mutations of the α4 residue. With ACh as the agonist, αS4A AChRs had a τo of ∼1.2 ms, which is not very different from that of the wild type, while the αS4I mutant had a τo of ∼0.36 ms (Fig. 4 and Table ). Further kinetic and dose–response analyses of the αS4I mutant in the presence of ACh are shown in Fig. 5. β2 ≅ 1,500 s−1, which is >30× slower than the wild-type's value. In this regard, αS4I resembles the αT3I mutant. Unlike the α3 mutant, however, α2 ≅ 2,777 s−1, which is similar to that of the wild type. Again, mutations at the α4 position mostly affect the channel opening rate constant. Dose–response analysis of αS4I indicates that this mutation decreases the K d, but less than approximately threefold (Fig. 5).

In summary, positions 3, 4, and 5 of the M2–M3L of the α subunit were probed using mutagenesis. Mutations in this region mainly affect channel gating with little effect on agonist binding. Hydrophobic substitutions at position 5 increase, and at positions 3 and 4 decrease, the channel opening rate constant.

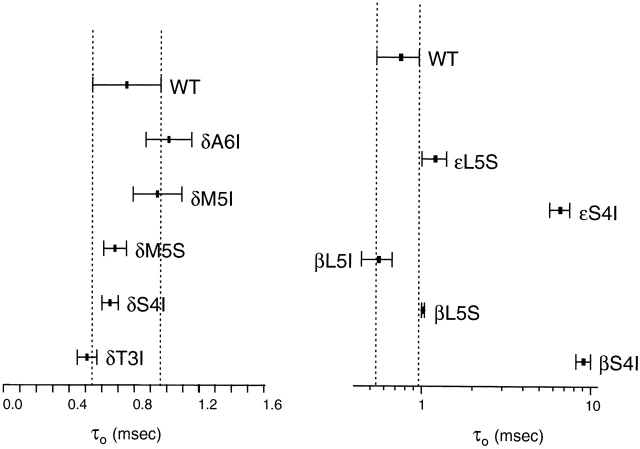

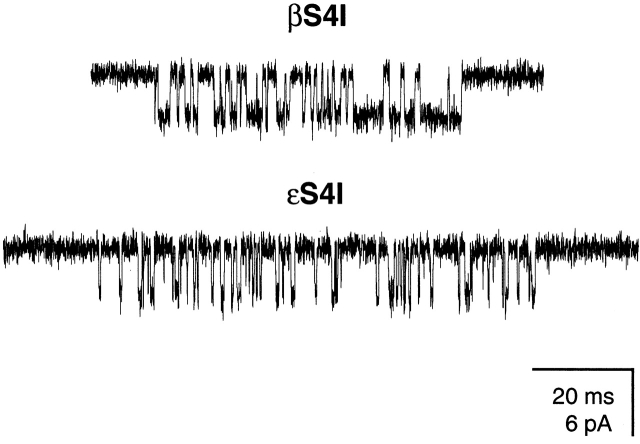

The M2–M3L Domain in Other Subunits

In the β and ε subunits, an S → I mutation in position 4 produced channels having prolonged τo values. With ACh as the agonist, τo was ∼9.1 ms for βS4I and 6.6 ms for εS4I AChRs, respectively (Fig. 6). Again, we quantified the effects of the mutations on the opening and closing rate constants using choline as the agonist (Fig. 7). For βS4I, β2 was ∼3.9-fold faster and α2 was ∼6.1-fold slower than the wild type (θ2 increased ∼23.5-fold). The effect of εS4I was less pronounced, as β2 was only ∼2.8-fold faster and α2 was ∼2.2-fold slower than in the wild type (θ2 increased approximately sixfold). Application of assuming that only τ0 changes upon mutation and using a σ value of 200 s−1 yields τo values of 3.7 and 2.2 ms for the βS4I and εS4I mutant receptors, respectively.

Figure 6.

Open-interval properties of β-, δ-, and ε-subunit M2–M3L mutants. Currents were recorded in the presence of 0.2 (β-, δ-, and ε-subunit mutants) or 1 (wild-type) μM ACh. The slowest open-time constant of each construct is indicated as the mean ± SD of three patches.

Figure 7.

Example single-channel clusters of βS4I and εS4I mutants in the presence of 20-mM choline. Display f c ≅ 6 kHz. Openings are downwards.

The δS4I mutation did not affect channel gating. We scanned nearby residues in δ by mutation to Ile, and none yielded AChRs having prolonged τo values (Fig. 6 and Table ).

Change in the Length of the M2–M3L

To explore the effect of changes in length, we engineered α-subunit mutants having longer or shorter M2–M3L regions. Decreasing the linker size by one residue shortened τo (∼0.28 ms), while adding one residue lengthened it (∼1.46 ms) (Fig. 4 and Table ). The briefer τo of the deletion mutant suggests that β2 is slower and α2 is ∼1.5-fold faster when the M2–M3L is shorter. The τo of the addition mutant suggests that β2 is faster, and/or α2 is slower, when the M2–M3L is longer.

Mapping the Gating Transition State at the M2–M3L

To probe the closed-like-vs.-open-like character of the M2–M3L at the gating transition state, we examined the correlation between rate and equilibrium constants of the gating reaction for the side-chain series at positions α3 (S, A, and I), α4 (S and I) and α5 (S, Q, C, and I). A linear correlation (“linear free-energy relationship;” Leffler and Grunwald 1963) is expected to hold when the conformation of the mutated region of the protein at the transition state is intermediate between the conformations in the open and closed states (Grosman and Auerbach 2000b; Grosman et al. 2000). The slope of the Brønsted plot (log rate constant vs. log equilibrium constant), Φ, is a measure of how “open” the probed region is when the transition state is reached, with Φ = 0 being fully closed and Φ = 1 being fully open.

For the α3 position, Φ = 0.789 ± 0.010 in the presence of ACh (the correlation coefficient between log β and log α is 0.985). For the α4 position, Φ = 0.971 in the presence of ACh as well (two-point relation). For the α5 position, Φ = 0.694 ± 0.028 in the presence of choline (Fig. 3 B; the correlation coefficient between log β and log α is 0.988). These results suggest that the conformation of the region around αS3-5 at the transition state of the gating allosteric transition is ≥70% open-like (≤30% closed-like). It is important to note that Φ values are likely to be insensitive to the nature of the particular ligand used as the agonist (Grosman et al. 2000) and, therefore, that Φ values estimated in the presence of choline are good estimates of the corresponding values in the presence of ACh.

Φ values of the β4 and ε4 positions were calculated from two-point relations. With choline as the agonist, these values were 0.431 in β and 0.568 in ε. The Φ value corresponding to the δ subunit, however, could not be measured because none of the tested mutations in the M2–M3L of this subunit caused a significant change in the gating equilibrium constant.

DISCUSSION

αS5I Is a Typical SCCMS Mutant

Like many other SCCMS mutants (Sigurdson and Auerbach 1994; Ohno et al. 1995), αS5I AChRs have a prolonged apparent open time (Table ), an increased sensitivity to the metabolite choline (Fig. 3 A and Zhou et al. 1999), and an increased spontaneous activity (Zhou et al. 1999). Our results suggest that the affinity ratio is largely unaffected by the αS5I mutation and, therefore, that the increased gating in the presence of ACh can be accounted for by a more favorable isomerization step (an increased unliganded gating equilibrium constant). Although the term “slow channel” that describes the SCCMS phenotype refers to the slow decay of the end-plate current, the predominant underlying mechanism of the disease is the accelerated channel opening: αS5I AChRs are hyperactive channels that open too fast. Along similar lines, “fast-channel” congenital myasthenic syndromes (e.g., εP121L; Ohno et al. 1996) are caused by sluggish AChRs that open too slowly.

Mechanistic Basis of the SCCMS Phenotype of αS5I Receptors

It is difficult to analyze the kinetic and dose–response properties of AChRs that open extremely rapidly, such as αS5I. The brevity of sojourns in the closed diliganded state results in many missed closures, and this distortion of the data makes it impossible to estimate binding and gating rate constants directly from the dwell-time series. Moreover, in these cases, the gating equilibrium constant is very large, hence the estimates of gating (θ2) and agonist-dissociation (K d) equilibrium constants obtained by fitting P open-vs.-concentration curves are ill-determined (i.e., have large coefficients of variation).

Another consequence of a very fast opening rate constant is that the EC50 value may no longer depend on the agonist affinity for the closed state of the receptor. According to Fig. 2, when θ2≫1,EC50≅J dθ0, where Jd is the microscopic dissociation equilibrium constant from the open state.

To overcome the limitations imposed by using ACh as the agonist, we analyzed the single-channel behavior of the αS5I mutant in the presence of choline, a low-efficacy agonist that opens the channel relatively slowly. In the presence of choline, we found that the mutation affects gating (∼28-fold increase in β2, ∼3.3-fold decrease in α2) while having little effect on agonist affinity for the closed state. The latter was also suggested by the analysis of P open-vs.-ACh concentration data of nearby mutations that decrease θ2 (αT3I, αT3A, and αS4I). Because the mutation increases the gating equilibrium constant to the same extent regardless of whether ACh or choline is bound to the receptor, we also suggest that the agonist affinity for the open channel is largely unaffected. These results clearly indicate that the predominant effect of the αS5I mutation is to favor the channel's isomerization step.

The observed prolongation of τo in the presence of ACh by the αS5I mutation was similar to the value predicted using , with σ equal to 200 s−1. Considering that open channels desensitize at a rate <10 s−1 (Auerbach and Akk 1998) and enter the CA 2* state (see Fig. 2) at a rate of ∼50 s−1 (Salamone et al. 1999), then ligand dissociation from the diliganded open state would occur at a rate of ∼140 s−1; that is, ∼70 s−1 from each binding site if they were equivalent. This value is ∼300× slower than the dissociation rate constant from the closed conformation, and (only) about three times faster than the dissociation rate constant from the desensitized state (Auerbach and Akk 1998).

Previous estimates of the agonist-dissociation rate constant from diliganded open AChRs consisted of calculations in the context of cyclic kinetic schemes, assuming microscopic reversibility and identical association rate constants of the agonist to the closed and open conformations. For ACh, values of 0.2 s−1 for adult-type (α2βδε; Edelstein et al. 1997) and 17.3 s−1 for fetal-type receptors (α2βδγ; Edelstein et al. 1996) can be found in the literature. Values of 0.02 s−1 for suberyldicholine bound to adult-type AChRs (Colquhoun and Sakmann 1985) and 40 s−1 for carbamylcholine bound to fetal-type AChRs (Jackson 1988) have also been reported.

Applying a similar approach, we can calculate the dissociation rate constant from diliganded open channels using published values of the agonist-dissociation rate constant from diliganded closed channels and the equilibrium constants of mono- and diliganded gating. For ACh bound to adult-type AChRs, values include 3.7 s−1 (from data in Ohno et al. 1996) and 96.5 s−1 (from data in Wang et al. 1997).

The reason for the disparity of these estimates is not clear, but is most likely related to inaccuracies in the identification of monoliganded openings (Lingle et al. 1992). Our approach, although having its own caveats, is an alternative one that not only avoids this pitfall, but also relieves the constraint of equal ACh-association rate constants to the closed and open forms of the channel.

Taken together, our results suggest that αS5I receptors can open as fast as at ∼1.4 × 106 s−1. Experiments with other very-fast-opening mutants, as well as confirmation of the σ value estimated here, are needed to explore the issue of a speed limit for AChR gating. An upper limit of 108 s−1 has been proposed for the T → R conformational change of hemoglobin (Eaton et al. 1991) and of 106 s−1 for protein folding (Hagen et al. 1996).

Mutational Analysis of the M2–M3L Domain

The results indicate that the hydrophobic amino acids Phe, Cys, and Ile at the α5 position increase the diliganded gating equilibrium constant and produce the SCCMS phenotype. The less hydrophobic residues Asp, Lys, Gln, Ala, and Ser result in wild-type–like gating. As noted before, the large variation in the size of these side chains indicates that residue volume is not a significant factor with regard to gating. It is also interesting that the α5 mutants have either a wild-type or an SCCMS-like phenotype, in spite of the variety of residues tested. Taken alone, this pattern would suggest that the local environment of αS5 changes from polar to nonpolar upon channel opening.

It is remarkable that similar modifications to adjacent residues in the M2–M3L have such diverse effects on gating. As opposed to the effect of S → I and S → A mutations at position α5, similar substitutions at positions α3 (T → I and T → A) or α4 (S → I) impair gating (i.e., decrease θ2), making the interpretation of the structure–function results less straightforward. This suggests a marked dependence of the effect of mutations on the position in the primary sequence of the M2–M3L. This pattern is different from that of other regions of the AChR like M2, where, regardless of the position, mutations have either little effect or favor (rather than impair) gating (e.g., Labarca et al. 1995; Grosman and Auerbach 2000a,Grosman and Auerbach 2000b).

The effect of M2–M3L mutations was different in the different subunits even though they were at positions that were homologous in terms of sequence. Even though mutations in β and ε yielded AChRs with increased θ2 values, characteristic of the SCCMS phenotype, position 4 was more sensitive to mutation than position 5, as opposed to the situation in the α subunit. Also, the τo values for the β- and ε-subunit mutants predicted by , assuming that only θ0 changes upon mutation and a value of 200 s−1 for σ, differ from the experimentally derived τo values. More experiments are needed to determine the agonist-binding properties of the β and ε M2–M3L mutants. Interestingly, mutations at positions δ3–6 did not have any effect on channel gating whatsoever. Thus, we conclude that, in the M2–M3L, homology in sequence does not coincide with homology in function. It is unlikely that this interpretation is caused by the vagaries of primary-structure alignment because the M2–M3L motif is very well conserved (Table ). That mutations in the δ subunit do not affect gating is yet additional evidence for the distinct role of this subunit in the receptor's function (Grosman and Auerbach 2000a,Grosman and Auerbach 2000b).

Physical Mechanism

It is remarkable that the gating behavior of the α-subunit M2–M3L mutants was trimodal, being either that of the wild type (αS5D, αS5K, and αS5A), of the SCCMS mutant αS5I (αS5I, αS5C, and αS5F), or of the αT3 mutants (αT3A, αT3I, and αS4I). Considering that these side chains cover a rather wide range of physicochemical properties, we would have expected to observe a continuum of gating phenotypes if the local environment of the side chains themselves had been a critical determinant of the gating equilibrium constant. Instead, the modality of the results suggests that the mutations cause the M2–M3L as a whole to adopt one of at least three conformations, each leading to a discrete phenotype.

M2–M3L Mutations in Other Receptors

Mutations of the M2–M3L domain have been studied in other ionotropic receptors. In glycine receptors, these have been shown to selectively impair gating (according to our numbering system: α1 R-3L, α1 R-3Q, α1 K2E, and α1 Y5C; Lynch et al. 1997), a conclusion that was confirmed by single-channel analysis of the α1 K2E mutant (Lewis et al. 1998). These results are similar to ours for the α3 position of muscle AChRs. In GABAC receptor ρ1 homomers, the R2A mutation (Kusama et al. 1994) increases the diliganded gating equilibrium constant, a result that is similar to ours for the S → I mutations at positions α5, β4, and ε4 of the muscle AChR. Mutation of position 5 of the neuronal AChR subunits α3, α7, or position 6 of β4 impair gating without affecting binding (Campos-Caro et al. 1996; Rovira et al. 1998, Rovira et al. 1999).

In summary, the M2–M3L is an important domain with regard to channel gating. However, whether it acts as the crucial transduction element between the binding sites and the pore, as it has often been suggested (e.g., Lynch et al. 1997), remains an open question. Mutagenesis data indicate that substitutions almost everywhere in the protein (including the binding sites) can affect the gating allosteric transition in the same way as those in the M2–M3L. This supports the notion that regions throughout the entire receptor are involved in the gating conformational change.

The M2–M3L and the Gating Reaction Pathway

Through Φ value analysis (Fersht 1999; Grosman et al. 2000), we estimated the position of the transition state along the gating-reaction pathway measured at the M2–M3L of the α, β, and ε subunits. In the α subunit, Φ ≥ 0.7. This suggests that, during the opening reaction, the closed → open conformational rearrangement of this domain is >70% complete at the transition state (or <30% complete when going in the open → closed direction). In the ε and β subunits, however, Φ was found to be ∼0.57 and ∼0.43, respectively. Φ values have been suggested to reflect the sequence of conformational rearrangements with the movement of regions having larger Φ values preceding those with smaller ones (Itzhaki et al. 1995; Villegas et al. 1998; Ternström et al. 1999; Grosman et al. 2000). Insofar as the M2–M3L residues of all subunits occupy similar locations in the quaternary structure of the AChR, this result suggests that the α subunit leads the conformational change in the opening direction, being followed by ε, and then by β, at least as far as the M2–M3L domains are concerned.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Lau for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to A. Auerbach (NS-23513) and S.M. Sine (NS-31744), the American Heart Association (New York State Affiliate) to C. Grosman, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (Medical Student Research Training Fellow) to F.N. Salamone, and the W.M. Keck Foundation to the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AChR, acetylcholine receptor channel; M2, second transmembrane segment; SCCMS, slow-channel congenital myasthenic syndrome.

References

- Akk G., Auerbach A. Inorganic, monovalent cations compete with agonists for the transmitter binding site of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2652–2658. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79834-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach A., Akk G. Desensitization of mouse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 1998;112:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, F.M., R. Brent, R.E. Kingston, D.D. Moore, J.G. Seidman, J.A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1992. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. 9.1.1–9.1.6.

- Campos-Caro A., Sala S., Ballesta J.J., Vicente-Agullo F., Criado M., Sala F. A single residue in the M2–M3 loop is a major determinant of coupling between binding and gating in neuronal nicotinic receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:6118–6123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Auerbach A. A distinct contribution of the δ subunit to acetylcholine receptor channel activation revealed by mutations of the M2 segment. Biophys. J. 1998;75:218–225. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B.N., Labarca C., Czyzyk L., Davidson N., Lester H.A. Tris+/Na+ permeability ratios of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are reduced by mutations near the intracellular end of the M2 region. J. Gen. Physiol. 1992;99:545–572. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.4.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D., Sakmann B. Fast events in single-channel currents activated by acetylcholine and its analogues at the frog muscle end-plate. J. Physiol. 1985;369:501–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D., Sigworth F.J. Fitting and statistical analysis of single-channel records. In: Sakmann B., Neher E., editors. Single-Channel Recording. Plenum Publishing Corp; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 483–585. [Google Scholar]

- Corringer P.J., Bertrand S., Galzi J.L., Devillers-Thiéry A., Changeux J.P., Bertrand D. Mutational analysis of the charge selectivity filter of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Neuron. 1999;22:831–843. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxen R., Newland C., Beeson D., Oosterhuis H., Chauplannaz G., Vincent A., Newsom-Davis J. Mutations in different functional domains of the human muscle acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit in patients with the slow-channel congenital myasthenic syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:767–774. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.5.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P.A., Pistis M., Hanna M.C., Peters J.A., Lambert J.J., Hales T.G., Kirkness E.F. The 5-HT3B subunit is a major determinant of serotonin-receptor function. Nature. 1999;397:359–363. doi: 10.1038/16941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Castillo J., Katz B. Interaction at endplate receptors between different choline derivatives. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1957;146:369–381. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1957.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W.A., Henry E.R., Hofrichter J. Application of linear free energy relations to protein conformational changesthe quaternary structural change of hemoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:4472–4475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein S.J., Schaad O., Henry E., Bertrand D., Changeux J.P. A kinetic mechanism for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors based on multiple allosteric transitions. Biol. Cybern. 1996;75:361–379. doi: 10.1007/s004220050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein S.J., Schaad O., Changeux J.P. Myasthenic nicotinic receptor mutant interpreted in terms of the allosteric model. Crit. Acad. Sci. (Paris). 1997;320:953–961. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(97)82468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds B., Gibb A.J., Colquhoun D. Mechanisms of activation of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and the time course of endplate currents. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:469–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science 1999. W.H. Freeman and Co; New York, NY: pp. 540–570 [Google Scholar]

- Filatov G.N., White M.M. The role of conserved leucines in the M2 domain of the acetylcholine receptor in channel gating. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.L., Macdonald R.L. The role of an α subtype M2-M3 His in regulating inhibition of GABAA receptor current by zinc and other divalent cations. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:2944–2953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02944.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galzi J.L., Devillers-Thiéry A., Hussy N., Bertrand S., Changeux J.P., Bertrand D. Mutations in the channel domain of a neuronal nicotinic receptor convert ion selectivity from cationic to anionic. Nature. 1992;359:500–505. doi: 10.1038/359500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosman C., Auerbach A. Kinetic, mechanistic, and structural aspects of unliganded gating of acetylcholine receptor channels. A single-channel study of M2 12′ mutants J. Gen. Physiol. 115 2000. 621 635a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosman C., Auerbach A. Asymmetric and independent contribution of M2 12′ residues to diliganded gating of acetylcholine receptor channels. A single-channel study with choline as the agonist J. Gen. Physiol. 115 2000. 637 651b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosman C., Zhou M., Auerbach A. Mapping the conformational wave of acetylcholine receptor channel gating. Nature. 2000;403:773–776. doi: 10.1038/35001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen S.J., Hofrichter J., Szabo A., Eaton W.A. Diffusion-limited contact formation in unfolded cytochrome cestimating the maximum rate of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11615–11617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill O.P., Marty A., Neher E., Sakmann B., Sigworth F.J. Improved patch clamp technique for high resolution current recordings from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoto K., Busch C., Sakmann B., Mishina M., Konno T., Nakai J., Bujo H., Mori Y., Fukuda K., Numa S. Rings of negatively charged amino acids determine the acetylcholine receptor channel conductance. Nature. 1988;335:645–648. doi: 10.1038/335645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki L.S., Otzen D.E., Fersht A.R. The structure of the transition state for folding of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 analyzed by protein engineering methodsevidence for a nucleation–condensation mechanism for protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;254:260–288. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M.B. Dependence of acetylcholine receptor channel kinetics on agonist concentration in cultured mouse muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1988;397:555–583. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin A., Akabas M.H. Toward a structural basis for the function of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their cousins. Neuron. 1995;15:1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusama T., Wang J.-B., Spivak C.E., Uhl G.R. Mutagenesis of the GABA ρ1 receptor alters agonist affinity and channel gating. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1209–1212. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199406020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarca C., Nowak M.W., Zhang H., Tang L., Deshpande P., Lester H.A. Channel gating governed symmetrically by conserved leucine residues in the M2 domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 1995;376:514–516. doi: 10.1038/376514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler J.E., Grunwald E. Rates and equilibria of organic reactions 1963. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: pp. 458 pp [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T.M., Sivilotti L.G., Colquhoun D., Gardiner R.M., Schoepfer R., Rees M. Properties of human glycine receptors containing the hyperekplexia mutation α1 (K276E), expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 1998;507:25–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.025bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingle C.J., Maconochie D., Steinbach J.H. Activation of skeletal muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Membr. Biol. 1992;126:195–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00232318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J.W., Rajendra S., Pierce K.D., Handford C.A., Barry P.H., Schofield P.R. Identification of intracellular and extracellular domains mediating signal transduction in the inhibitory glycine receptor chloride channel. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1997;16:110–120. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby K.L., Stevens C.F. The effect of voltage on the time course of end-plate currents. J. Physiol. 1972;223:151–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic S.J., Ye Q., Wick M.J., Koltchine V.V., Krasowski M.D., Finn S.E., Mascia M.P., Valenzuela C.F., Hanson K.H., Greenblatt E.P. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J.-P. On the nature of allosteric transitionsa plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K., Hutchinson D.O., Milone M., Brengman J.M., Bouzat C., Sine S.M., Engel A.G. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by prolonged acetylcholine receptor channel openings due to a mutation in the M2 domain of the ε subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:758–762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K., Wang H.-L., Milone M., Bren N., Brengman J.M., Nakano S., Quiram P., Pruitt J.N., Sine S.M., Engel A.G. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by decreased agonist binding affinity due to a mutation in the acetylcholine receptor ε subunit. Neuron. 1996;17:157–170. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortells M.O., Lunt G.G. Evolutionary history of the ligand-gated ion-channel superfamily of receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F., Auerbach A., Sachs F. Estimating single-channel kinetic parameters from idealized patch-clamp data containing missed events. Biophys. J. 1996;70:264–280. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F., Auerbach A., Sachs F. Maximum likelihood estimation of aggregated Markov processes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1997;264:375–383. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovira J.C., Ballesta J.J., Vicente-Agullo F., Campos-Caro A., Criado M., Sala F., Sala S. A residue in the middle of the M2–M3 loop of the beta4 subunit specifically affects gating of neuronal nicotinic receptors. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00889-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovira J.C., Vicente-Agullo F., Campos-Caro A., Criado M., Sala F., Sala S., Ballesta J.J. Gating of alpha3beta4 neuronal nicotinic receptor can be controlled by the loop M2–M3 of both alpha3 and beta4 subunits. Pflügers Arch. 1999;439:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s004249900143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs F., Neil J., Barkakati N. The automated analysis of data from single ionic channels. Pflügers Arch. 1982;395:331–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00580798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B., Patlak J., Neher E. Single acetylcholine-activated channels show burst-kinetics in presence of desensitizing concentrations of agonist. Nature. 1980;286:71–73. doi: 10.1038/286071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone F.N., Zhou M., Auerbach A. A re-examination of adult mouse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel activation kinetics. J. Physiol. 1999;516:315–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0315v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepfer R., Conroy W.G., Whiting P., Gore M., Lindstrom J. Brain α-bungarotoxin binding protein cDNAs and Mabs reveal subtypes of this branch of the ligand-gated ion channel gene superfamily. Neuron. 1990;5:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90031-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson, W., and A. Auerbach. 1994. Frequent, long-lived spontaneous and mono-liganded openings of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with M2 mutations. Neuroscience Society Annual Meeting Abstract. 20:1132.

- Sigworth F.J., Sine S.M. Data transformations for improved display and fitting of single channel dwell-time histograms. Biophys. J. 1987;52:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83298-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sine S.M. Molecular dissection of subunit interfaces in the acetylcholine receptoridentification of residues that determine curare selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:9436–9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternström T., Mayor U., Akke M., Oliveberg M. From snapshot to movieΦ analysis of protein folding transition states taken one step further. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14854–14859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarroel A., Herlitze S., Koenen M., Sakmann B. Location of a threonine residue in the α-subunit M2 transmembrane segment that determines the ion flow through the acetylcholine receptor channel. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1991;243:69–74. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas V., Martínez J.C., Avilés F.X., Serrano Luis. Structure of the transition state in the folding process of human procarboxypeptidase A2 activation domain. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;283:1027–1036. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.L., Auerbach A., Bren N., Ohno K., Engel A.G., Sine S.M. Mutation in the M1 domain of the acetylcholine receptor α subunit decreases the rate of agonist dissociation. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;109:757–766. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamyatnin A.A. Protein volume in solution. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1972;24:109–123. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(72)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Engel A.G., Auerbach A. Serum choline activates mutant acetylcholine receptors that cause slow channel congenital myasthenic syndromes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10466–10471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]