SYNOPSIS

In 2002, the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice (NWCPHP) at the University of Washington initiated the Epidemiology Competencies Project, with the goal of developing competency-based epidemiology training for non-epidemiologist public health practitioners in the northwestern United States. An advisory committee consisting of epidemiology faculty and experienced public health practitioners developed the epidemiology competencies. NWCPHP used the competencies to guide the development of in-person trainings, a series of online epidemiology modules, and a Web-based repository of epidemiology teaching materials. The epidemiology competencies provided a framework for collaborative work between NWCPHP and local and regional public health partners to develop trainings that best met the needs of a particular public health organization. Evaluation surveys indicated a high level of satisfaction with the online epidemiology modules developed from the epidemiology competencies. However, measuring the effectiveness of -competency-based epidemiology training for expanding epidemiology knowledge and skills of the public health workforce remains a challenge.

Epidemiology is widely accepted as a core public health science, but public health practitioners have varying levels of experience with, expertise in, or need for epidemiologic skills. Historically, there was no requirement for non-epidemiologists to have epidemiology expertise. However, in light of recent public health emergency preparedness and response needs, there has been a realization that all public health workers should have a minimum level of fluency in epidemiology.1 Moreover, there is concern that even public health practitioners working as epidemiologists may have gaps in their knowledge of the discipline.

In a 2004 assessment of epidemiologic capacity in state health departments conducted by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), 48% of epidemiologists surveyed reported having had no academic coursework in epidemiology.2 Additionally, the report found that approximately 29% of state health departments reported that 50% or fewer of their epidemiologists had participated in training or education in 2003. CSTE concluded the following: “To help mitigate perceived training gaps, a national standard for competency-based, on-the-job training and/or a certificate program should be established to ensure proper training of epidemiologists.”

Also in 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and CSTE convened an expert advisory group to define a set of applied epidemiology competencies for epidemiologists working in federal, state, and local health departments. The final set of Competencies for Applied Epidemiologists in Governmental Public Health Agencies (AECs) became available in 2006.3 In 2002, prior to this national effort, the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice (NWCPHP) at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle began developing a set of epidemiology competencies for non-epidemiologist public health practitioners in the northwestern United States.

NWCPHP was founded in 1991 with the help of funds from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). In 2000, it became both a center for public health preparedness, through funding from CDC and the Association of Schools of Public Health, and a public health training center, funded by HRSA. The mission of NWCPHP is to improve the quality and effectiveness of public health practice in the northwestern U.S. by linking academia and the practice community. NWCPHP works with state and local health agencies and tribal health organizations as part of a six-state regional partner network—including Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming—to develop and implement a long-term, integrated approach to workforce development. This network helps NWCPHP set goals and priorities and also provides mutual resources and support for its members.

One of the themes that arose through regular communication between NWCPHP and its public health partners was the need for development and maintenance of epidemiology knowledge and skills among public health practitioners, even those not specifically employed as epidemiologists. This feedback, along with data from national studies, indicated that providing continuing education in practice-based epidemiology must therefore be a key activity for public health workforce development. Recent workforce development trends support competency-based training in many areas of public health practice.4–10 To better respond to the needs of Northwest public health partners and to help develop epidemiology trainings for the regional network, NWCPHP initiated the Epidemiology Competencies Project.

METHODS

Development of the NWCPHP epidemiology competencies

In 2002, NWCPHP convened an advisory committee of UW epidemiology faculty and experienced public health practitioners to develop a set of epidemiology competencies for public health workers in the northwestern U.S. The goal was to create a set of competencies, subcompetencies, and learning objectives for public health workers to help NWCPHP faculty develop epidemiology trainings for non-epidemiologist public health practitioners; provide a framework for NWCPHP partners to develop their own trainings or measures of competency in epidemiology; and develop a repository for competency-based training resources, including case studies and short learning modules.

The NWCPHP epidemiology competencies were designed to be flexible and modular to meet the variable conditions that must be considered in the development of trainings, including: the medium for delivery (e.g., online vs. in-person training), the public health practice audience (e.g., frontline staff vs. senior-level management), duration (from 0.5 to 5 days), and the specific needs of the public health organization requesting the training.

Reference materials used to develop the epidemiology competencies included: (1) two existing competency sets for public health practitioners (Emergency Preparedness Core Competencies for Public Health Workers11,12 and Informatics Competencies for Public Health Professionals13) and (2) epidemiology textbooks and introductory epidemiology course syllabi. A master list of approximately 120 learning objectives was generated. The objectives represented the range of epidemiology knowledge and skills that would be important for public health practitioners with variable needs for epidemiology knowledge and skills to perform their job functions. The advisory committee organized and synthesized the list of learning objectives into nine competencies. Because the purpose of the competency set was to help faculty develop epidemiology trainings and identify materials that could be tailored to meet the particular needs of NWCPHP regional partners, the set of competencies was further divided into subcompetencies to facilitate inclusion or exclusion of general topic areas in training development and evaluation (Figure 1). The compete list of competencies, subcompetencies, and learning objectives can also be viewed on the Epi Competencies page of the NWCPHP website.14

Figure 1.

NWCPHP epidemiology competencies and subcompetencies

NWCPHP = Northwest Center for Public Health Practice

Application to training development

NWCPHP epidemiology competencies have been used to guide the development of numerous online and in-person trainings for public health practitioners in the northwestern U.S. Additionally, NWCPHP identified, organized, and compiled an online repository of practice-based instructional materials that map to each competency and to specific learning objectives.

Self-paced online modules

NWCPHP developed a set of self-paced, online modules to provide epidemiology learning opportunities for local, state, and tribal public health professionals. Following the modular design of the epidemiology competencies, these online modules were deliberately created as distinct units. The intent was to provide learners with the choice of taking the full set of modules for a more comprehensive exposure to the discipline of epidemiology or taking a single module for training in a specific topic area.

As of 2007, four online modules have been created. Introduction to Public Health Surveillance, based on competency 4 (define, describe, interpret, and install public health surveillance systems), gives an overview of surveillance systems in local, state, and national public health practice.15 The course explains the history of and legal basis for surveillance, definitions and types of surveillance, attributes and limitations of surveillance systems, and examples of national and state systems. Basic Concepts in Infectious Disease Epidemiology (competency 3: define terms and concepts associated with infectious diseases) provides an introduction to the concepts and principles of infectious disease, including agents and hosts, transmission characteristics, epidemiologic methods, and vaccination and other control measures.16 Introduction to Outbreak Investigation (competency 2: design and conduct an outbreak investigation) walks learners through the steps involved in an outbreak investigation, including determining whether an outbreak exists, establishing a case definition, descriptive epidemiology, principles of generating and testing hypotheses, and how to communicate findings.17 Additionally, the module reviews the roles of teams and people who are typically involved in investigations. Data Interpretation for Public Health Professionals (competency 5: obtain, evaluate, and interpret public health information) presents core epidemiologic and biostatistic terms and concepts, such as rates and counts, prevalence, incidence, mortality, crude vs. category-specific rates, confidence intervals, and p-values, and explains how to define and interpret each.18 Practical uses, such as when to use graphs and tables, where to find data sources, and how to read, interpret, and present public health data, are also covered.

Online module development was a complex process that averaged seven months per module. The process included convening multidisciplinary development/production teams, engaging the NWCPHP's regional network partners in content ideas, and recruiting public health workers from the state, local, and tribal levels to serve as pilot testers.

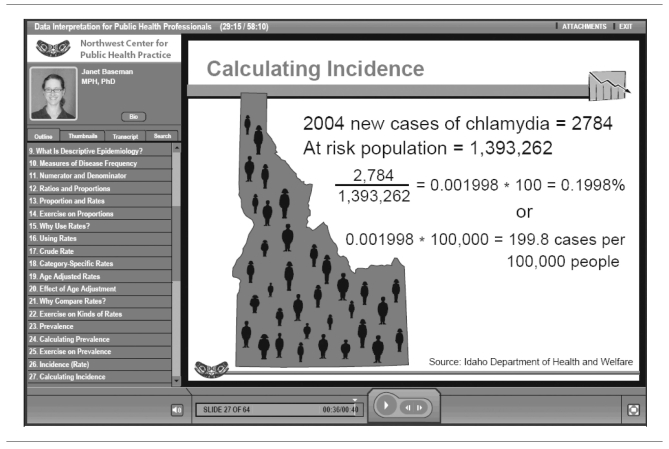

Members of the development/production team included instructional designers, subject matter experts, graphic designers, editors, and an outreach facilitator. The team worked together to create user-friendly modules that presented complex concepts in a simple and straightforward manner, specifically for learners with little to no epidemiology training. The design process began by selecting the competency, subcompetencies, and learning objectives for the module topic area. Once a set of learning objectives was selected for the training, content experts worked from the objectives to create an initial set of PowerPoint slides. With assistance from instructional and graphic designers, the content was organized, simplified, and illustrated to be optimally effective for adult learners. The narrator (a subject matter expert) wrote and recorded a script, and the technical production team converted the slides into a self-playing, audio-narrated module with interactive test-your-knowledge exercises and a posttest using Articulate® software.19 Figure 2 shows a screenshot of the Data Interpretation for Public Health Professionals module within Articulate.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Northwest Center for Public Health Practice Data Interpretation for Public Health Professionals online module

In the early stages of development, regional network partners were kept apprised of the topics and given the opportunity to discuss and comment on the plans. As each module neared completion, the NWCPHP outreach facilitator worked with regional network partners to recruit public health practitioners who met the intended target audience criteria, as well as a few subject matter experts from the practice community, to pilot test the module. Reviewers were surveyed about the depth of the content, clarity of instruction, quality of presentation, applicability to practice, and other technical qualities of the module.

Frontline public health partners were especially involved in the development of the Outbreak Investigation and Data Interpretation modules. NWCPHP partnered with a local communicable disease-control expert to serve as the primary content developer and narrator for the Outbreak Investigation module. This shared development approach was chosen so that a truly practice-based perspective could be incorporated, including lessons from the field. The content followed the subcompetencies outlined in the epidemiology competencies, although not all subcompetencies were covered in the one-hour trainings.

The Data Interpretation module was specifically requested by the Idaho Department of Human Welfare (IDHW) to be used for training frontline public health workers with no epidemiologic or statistical training but who needed to be able to read, interpret, and present public health data. One specification was that the module not only be appropriate for those without prior training, but also not be intimidating. Therefore, careful consideration was paid to ensure that common vernacular rather than epidemiologic jargon was used in the instructional materials.

In the initial planning, NWCPHP provided IDHW with two competencies from which to choose: competency 5 (obtain, evaluate, and interpret public health information) and competency 6 (collect, organize, prepare, and display epidemiologic data) to guide them in determining the scope and objectives of the training. The IDHW health directors, aided by epidemiologists and educational coordinators, selected subcompetencies from the two proposed competencies. Subsequent discussions with NWCPHP content experts helped pare down the volume of requested topics and solidify a manageable outline for a one-hour course that met the stated needs of the health department. Throughout the development process, drafts were reviewed by IDHW health educators and epidemiologists, who also provided state-specific data examples for inclusion in the module. Pilot testing involved both Idaho end-users and other practitioners from the Northwest region.

After fine-tuning each module based on pilot test feedback, the completed versions were provided to the public at no cost. The modules were advertised via the NWCPHP website and training listserv, regional network partners, pilot testers, and other national training databases and websites.2,21 Several of NWCPHP's state health department partners chose to offer these courses from their learning management system (LMS) to track the applied use of these trainings within their states. These modules can also be launched and played from NWCPHP's website, which provides access to partner states without their own LMS and to other national and even international learners.

In-person trainings and other materials

In partnership with regional Northwest public health agencies, NWCPHP offers trainings in epidemiology for non-epidemiologists periodically throughout the year, often as part of residential training institutes. Although many of the epidemiology courses for these training institutes were created prior to the development of the epidemiology competencies, the competencies have been used to revise existing courses (such as for the annual Northwest Summer Institute for Public Health Practice) and customize new courses.

NWCPHP relies on the modular framework of the competency set to guide discussions with partners about content changes, and the list of competencies is frequently sent to partners for their review. Epidemiology courses are consistently taught by NWCPHP faculty at annual trainings across the Pacific Northwest, though the focus areas for these trainings change as public health partners request trainings in topic areas not addressed in previous years' trainings.

The process for mapping NWCPHP competencies to the curricula of in-person trainings included a review of the full competency set with public health officials from the state requesting the training and identification of competencies and subcompetencies of particular interest to the state. NWCPHP faculty and staff communicated regularly with officials from the state until a mutually agreed-upon list of learning objectives was developed, at which point content development for the training began. An example of the utility of this process was the development of a new NWCPHP epidemiology training titled Assessing Disease Occurrence: Collecting New Data (Surveys), a course that maps to NWCPHP competency 8 (design and implement surveys and questionnaires) and was developed through the process described previously. This course was recently taught at the 2007 Annual Oregon Public Health Conference.

In addition to the short, modular courses and in-person trainings, NWCPHP has also created a Web-based epidemiology repository, accessible through the NWCPHP website, to facilitate just-in-time learning. The repository contains practice-based instructional materials, including case studies and short learning modules, which can be used by local trainers as tools to create competency-based trainings. Electronic versions of 20 CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service case studies are also available in a format that is searchable by competency, agent, and mode of transmission.22 For each case study, a cover sheet details the setting, type of agent, mode of transmission, learning objectives, competency addressed, and source of the case, to aid in selection of an appropriate case study for specific training needs. Additionally, tips for teaching with case studies are available on the NWCPHP website.23

RESULTS

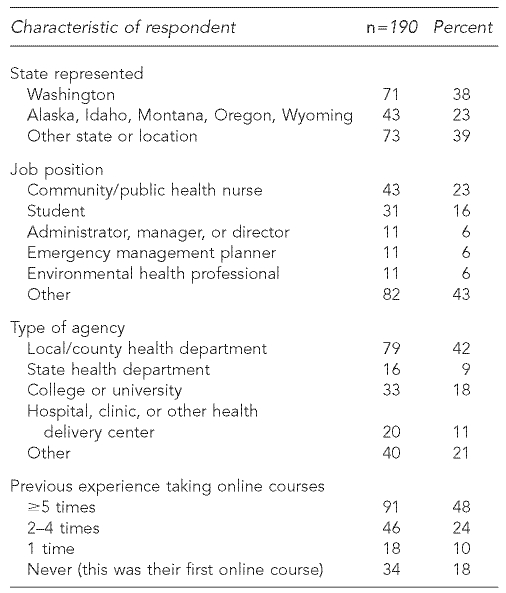

NWCPHP uses post-course user surveys to gather feedback about the quality of all of its trainings. Surveys are administered via a Web-based survey tool. No individually identifiable information is collected, but some demographic questions are included so that NWCPHP can track and assess descriptive characteristics of people who completed the trainings. Characteristics of 190 participants who completed at least one of the four online courses as of January 19, 2007, are presented in the Table.

Table.

Descriptive characteristics of public health practitioners who completed one or more NWCPHP online epidemiology training modules

NWCPHP = Northwest Center for Public Health Practice

As shown in the Table, community or public health nursing was the largest single job position represented (23%). Overall, 61% of participants were from northwestern states, with the majority of those being from Washington State. The remaining 39% of trainees represented 23 other states, the District of Columbia, and 10 locations outside the U.S. Local, county, and state health agencies accounted for half of all participants. Nearly half (48%) of participants reported having participated in five or more online courses previously. Convenient online access to the training received many compliments from users, as did the use of scenarios and interactive quizzes.

A large majority (94%) of trainees reported completing the courses in two hours or less, with 84% of participants indicating that the level of complexity of the courses was “about right.” In general, there were high levels of satisfaction with the online modules, with 90% of Outbreak Investigation and Data Interpretation participants and 85% of Infectious Disease Concepts participants rating the courses excellent or very good. A smaller proportion of participants (67%) rated the Public Health Surveillance course as excellent or very good.

DISCUSSION

During the past four years, in response to the need for well-developed epidemiology competencies that can be used to develop trainings for non-epidemiologist public health practitioners, NWCPHP developed a set of epidemiology competencies and applied them to the development of both in-person and online epidemiology trainings. The NWCPHP epidemiology competencies have also been used by the Washington State Department of Health for the development of Community Health Assessment Competencies for Washington State Public Health Staff.24

One of the basic differences between the AECs and those described in this article is in the target audiences. The AECs were designed to define areas of competence for epidemiologists practicing in governmental public health agencies at the local, state, or federal level. The NWCPHP epidemiology competencies were designed to meet the needs of a different audience: (1) non-epidemiologists, especially at the local level, who make direct use of certain epidemiologic tools in their work, (2) public health practitioners who interact regularly with trained epidemiologists at any level and could benefit from a better understanding of epidemiology, and (3) practitioners who work as epidemiologists and are looking for teaching resources. In spite of these differences, there is some overlap between learning objectives for both the non-epidemiologist audience of the NWCPHP competencies and the entry-level epidemiologist audience of the AECs. For example, competency in generating hypotheses and interpretation of measures of association, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals were topics included in both competency sets.

NWCPHP has found the epidemiology competencies to be useful in developing appropriate epidemiology trainings for public health partners in the Pacific Northwest. When the competencies were distributed to public health partners for review, some training requestors did not always know what their training goals were because they had not defined their own needs. In such instances, NWCPHP worked with public health partners to develop surveys to poll potential trainees about their needs and interests. Having a readily available list of competencies, subcompetencies, and learning objectives to select from has been invaluable in developing surveys and establishing both a starting point and an infrastructure for communication with public health practice partners.

The NWCPHP Epidemiology Competencies Project has demonstrated that epidemiology competencies can be used effectively to guide development of in-person and online trainings for public health practitioners, and that mapping competencies to training materials in a Web-based repository provides a valuable resource to both public health trainers and trainees. Public health practitioners who participated in NWCPHP online epidemiology trainings reported several potential uses of the information contained in the trainings, including preparing guidelines and emergency plans, training others, and using the information in clinical practice. Though these potential uses of knowledge and skills gained from NWCPHP's online modules are positive and are in line with the intentions of course developers, it is important to note that the majority of trainees indicated a high degree of experience using online training courses. This raises the question of whether or not these trainings are reaching only a certain portion of the intended target audience (i.e., more computer-savvy individuals or organizations with access to the Internet).

Challenges

Although the NWCPHP course evaluation surveys have been invaluable in subsequent course design, determining whether these trainings have expanded trainees' epidemiologic knowledge and skills or increased partner agencies' epidemiologic capacity of NWCPHP is a major measurement challenge. The course evaluation surveys request information about anticipated use of the material, but follow-up surveys with trainees have not been possible to date. Many of NWCPHP's partners are investing in an LMS that will allow them to track employees who have completed the courses so that the effectiveness of a specific training on epidemiology competence can be measured on an individual basis.

Currently, subjective assessments are frequently used to measure the value of training (e.g., trainees report perceived levels of competency in particular areas). A more valid approach might be to use LMS to track those who are enrolled in or have completed a specific training. An assessment of epidemiologic skills could be conducted prior to the training (a pretest competency assessment), and follow-up skills-based assessments (posttest competency assessments) could be conducted after allowing time for skills to be used on the job. For the purposes of comparison and quantification of the benefits of training, the same competency assessments could be administered to two groups of employees within a public health agency—those who participated in the training and those who did not, effectively a cohort study design.

Agency-level epidemiologic capacity is even more difficult to measure. NWCPHP has done statewide and organization-wide (in the case of the tribal health partners) needs assessments in the past, but due to health department staff turnover, multiple delivery systems for available trainings, and no comprehensive (or failsafe) methods to track and measure these influences, follow-up needs assessments would be insufficient to accurately assess institutional competency gains, let alone what proportion of any gains were attributable to NWCPHP trainings. Use of LMS and competency-based skills assessments to track cohorts of practitioners who have and have not participated in epidemiologic trainings could be used to measure improvements over time in agency-level epidemiologic capacity, though large numbers of participants would likely be necessary to see an effect.

CONCLUSION

Despite these measurement challenges, NWCPHP has found the epidemiology competencies to be useful for training development. Therefore, it is our recommendation that competency-based development of training continue, but that those who apply the competencies to public health workforce development carefully consider the issue of impact measurement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Kobayashi for review of the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice (NWCPHP) epidemiology competencies and Sandy Senter and Maggie Jones for assistance in analysis of NWCPHP evaluation data. The authors also thank Jack Thompson (Director, NWCPHP) and Luann D'Ambrosio (Assistant Director, NWCPHP) for their support and guidance throughout the duration of the Epidemiology Competencies Project and subsequent development of epidemiologic trainings.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants #S1554-20/21 and #A1015-22/22 from the Association of Schools of Public Health/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cooperative Agreements for the NWCPHP, by grant #U90/CCU024247 from CDC for the NWCPHP, and by grant #D20 HP00007 from the Human Resources and Services Administration for the Public Health Training Centers.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Markenson D, DiMaggio C, Redlener I. Preparing health professions students for terrorism, disaster, and public health emergencies: core competencies. Acad Med. 2005;80:517–26. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assessment of epidemiologic capacity in state and territorial health departments—United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(18):457–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) and Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Competencies for applied epidemiologists in governmental public health agencies (AECs) [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/od/owcd/cdd/aec or http://www.cste.org/competencies.asp.

- 4.Horney JA, Sollecito W, Alexander LK. Competency-based preparedness training for public health practitioners. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2005;11:S147–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebbie K, Merrill J, Hwang I, Gupta M, Btoush R, Wagner M. Identifying individual competency in emerging areas of practice: an applied approach. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:990–9. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karras BT, O'Carroll P, Oberle MW, Masuda D, Lober WB, Robins LS, et al. Development and evaluation of public health informatics at University of Washington. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2002;8:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison F, Malpas C, Kukafka R. Development of competency-based on-line public health informatics tutorials: accessing and using on-line public health data and information. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:944. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talbot L, Graham M, James EL. A role for workforce competencies in evidence-based health promotion education. Promot Educ. 2007;14:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter KF, Kaiser KL, O'Hare PA, Callister LC. Use of PHN competencies and ACHNE essentials to develop teaching-learning strategies for generalist C/PHN curricula. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:146–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreitner S, Leet TL, Baker EA, Maylahn C, Brownson RC. Assessing the competencies and training needs for public health professionals managing chronic disease prevention programs. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:284–90. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebbie K, Merrill J. Public health worker competencies for emergency response. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2002;8:73–81. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Health Policy, Columbia University School of Nursing. Core public health worker competencies for emergency preparedness and response. 2001. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.doh.state.fl.us/chdCharlotte/documents/Competencies.pdf.

- 13.Public Health Informatics Competencies Working Group, Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Informatics competencies for public health professionals. 2002. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://nwcphp.org/resources/phicomps.v1.

- 14.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community medicine. Epi competencies. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/epi/competencies.

- 15.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Introduction to public health surveillance. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/introphsurv.

- 16.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Basic infectious disease concepts in epidemiology. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/infectious.

- 17.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Introduction to outbreak investigation. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/outbreak.

- 18.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Data interpretation for public health professionals. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/data.

- 19.Articulate Global Inc. Articulate Presenter: Version 5.2. New York: Articulate Global Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Public Health Preparedness Resource Center. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://asph.org/acphp/resultsAdvance.cfm.

- 21.National Public Health Training Center Network Distance Education Center. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.asph.org/phtc/search.cfm.

- 22.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Case studies for use in public health epidemiology instruction. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/epi/casestudies.

- 23.Northwest Center for Public Health Practice, University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine. Teaching strategies: tips for teaching case studies. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.nwcphp.org/epi/teach.

- 24.Washington State Department of Health. Community health assessment competencies for Washington State Public Health staff. [cited 2007 Oct 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.assessnow.info/orientation/community-health-assessment-competencies-for-washington-state-public-health-staff.