SYNOPSIS

The Florida Epidemic Intelligence Service Program was created in 2001 to increase epidemiologic capacity within the state. Patterned after applied epidemiology training programs such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epidemic Intelligence Service and the California Epidemiologic Investigation Service, the two-year postgraduate program is designed to train public leaders of the future. The long-term goal is to increase the capacity of the Florida Department of Health to respond to new challenges in disease control and prevention. Placement is with experienced epidemiologists in county health departments/consortia. Fellows participate in didactic and experiential components, and complete core activities for learning as evidence of competency. As evidenced by graduate employment, the program is successfully meeting its goal. As of 2006, three classes (n=18) have graduated. Among graduates, 83% are employed as epidemiologists, 67% in Florida. Training in local health departments and an emphasis on graduate retention may assist states in strengthening their epidemiologic capacity.

This article describes the development and present status of the Florida Epidemic Intelligence Service (FL-EIS), an applied epidemiology training program (AETP) that began as an initiative to increase epidemiologic capacity in Florida in 2001. However, to provide a context for discussion of this program, a review of the historical background of applied epidemiology training, assessment of epidemiologic capacity, and development of recommended competencies for epidemiologists are provided as a preface.

BACKGROUND

Applied epidemiology training in the U.S. has its roots in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epidemic Intelligence Service (CDC EIS). CDC EIS was the vision of Joseph Mountin, founder of CDC, and was implemented in 1951 by Alexander Langmuir, CDC Chief Epidemiologist, to enhance epidemiologic capacity for disease outbreak investigation and response and to provide a cohort of trained field epidemiologists.1,2 Modeled on the premise of a clinical postgraduate residency program, CDC EIS was established as a combined training and service program to train health professionals in applied epidemiology and other public health competencies.3 Since the first class of 22 physicians and one sanitary engineer enrolled in 1951, more than 2,500 professionals have completed the program.1 In terms of employment setting choices, field officers (those trained in state or local health departments) are more likely than those trained at CDC headquarters to choose state or local health departments after graduation.4

The success of the CDC EIS led to the development of similar AETPs, often known as field epidemiology training programs (FETPs)3 or field epidemiology and laboratory training programs (FELTPs) (Personal communication, Steven Wiersma, MD, MPH, Division of Viral Hepatitis, CDC, November 2006) in other countries such as Thailand, Australia, Uganda, Germany, Korea, and India. As of January 2001, AETPs have been established in 28 countries, producing an estimated 945 graduates, with another 400+ people in training.3 A global network of AETPs was incorporated in 1999 as the Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network (TEPHINET) and has 32 participating programs.5

Despite the strong national and international examples, development of state-based programs in the U.S. lagged behind. In 1988, the California Department of Health Services established the California Epidemiologic Investigation Service (Cal-EIS), a one-year AETP, which had 80 graduates by 1995.6 Similarly, Florida established the FL-EIS in 2001.7,8 In conjunction with CDC, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) also established an epidemiology fellowship program in 2003, training an average of eight to 14 fellows in each class.9

Assessment of epidemiologic capacity in state and territorial health departments

Public health agencies often struggle to maintain an adequate workforce. In November 2001, CSTE conducted a survey of state and territorial health departments to assess their ability to conduct core epidemiologic activities.10 This was the first comprehensive national assessment of epidemiologic capacity and it demonstrated deficiencies in a number of areas. Collectively, the responding state and territorial health departments reported 1,366 people employed as epidemiologists. Among these, 787 (42.4%) had no formal training in epidemiology, either coursework or applied epidemiology training. In general, states reported that their capacity in all program areas (chronic disease, maternal/child health, injury, bioterrorism/emergency management, environmental health, oral health, and occupational health) were inadequate to meet their needs, except for infectious disease. Additionally, “partial” or “minimal to no” capacity was reported by 40% to 93% or more of states in essential services of public health that rely heavily on epidemiologic components, such as monitoring health status to identify and solve community health problems, diagnosing and investigating health problems in the community, evaluating effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of population-based services, and conducting research.10

Subsequently in 2004, CSTE conducted a follow-up survey.11 While there was some variability between the two surveys affecting comparability, the 2004 survey found there had been an increase in the overall number of epidemiologists employed in state and territorial health departments, increased capacity in terrorism preparedness and emergency response and in maternal-child health, but decreased capacity in the other six program areas (infectious disease, chronic disease, environmental health, injury, oral health, and occupational health) compared with the 2001 survey.11 The number of epidemiologists without some type of formal epidemiology training decreased from 42% to 29%. While the distribution of $1 billion in terrorism preparedness and emergency response funds provided additional epidemiologic capacity by 2004, it was reported that a 47% increase from the current number of practicing epidemiologists was needed.11 These findings suggest that applied epidemiology training may help fill this void.

CDC/CSTE development of applied epidemiology competencies

In January 2004, CDC and CSTE hosted a forum to address workforce issues affecting public health epidemiologists and subsequently convened an expert panel to define competencies for applied epidemiology for local, state, and federal public health epidemiologists.12 They defined three tiers of epidemiologists (frontline, mid-level, and senior level) and defined eight skill domains, derived from the Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice, essential to the effective practice of epidemiology. This includes skills in assessment and analysis, basic public health science, communication, community dimensions of practice, cultural competency, financial and operational planning and management, leadership and systems thinking, and policy development. Tier 2—mid-level competencies—are appropriate for AETPs to consider as part of instructional competencies.12

Healthy People 2010 objectives, a national framework for prevention geared toward increasing the quality and years of healthy life and eliminating health disparities, provides guidance on epidemiologic indicators that are needed for the 28 focus areas established as public health priorities.13,14 Specifically, objective 23-14 calls for “increases in health agencies that provide or ensure comprehensive epidemiology services to support essential public health services.”10,14

FL-EIS PROGRAM

FL-EIS—a two-year supervised field epidemiology experience with a mentor in a Florida county health department—was established by emergency order in October 2001 as part of the state's response to terrorism following 9/11. However, the vision for the program and plans to create it were well underway a year before this event. State officials' awareness of successful FETPs, coupled with the recognition of a growing need to increase the epidemiologic capacity not only at the state, but also at the county level, led to exploration and planning for the FL-EIS program. As part of this planning, Florida Department of Health (FDOH) officials had extensive conversations and consultation with the director of the only state-based EIS program at that time, Cal-EIS (Personal communication, Steven Wiersma, MD, MPH, Division of Viral Hepatitis, CDC, November 2006). In January 2002, the creation of this new two-year postgraduate program was announced. Patterned after AETPs like the CDC EIS and the Cal-EIS, the specific mission of the FL-EIS program is to train public health leaders of the future. The long-term goal is to increase the capacity of FDOH and its county health departments to respond to new challenges in disease control and prevention.

From its inception, the program has been administratively housed in the headquarters of the FDOH Bureau of Epidemiology (BOE), which has a long history of training CDC EIS officers. From 1953 to 2004, 31 CDC EIS officers were assigned to FDOH BOE (Personal communication, Lisa Pealer, PhD, CDC Office of Workforce and Career Development, August 2006). While many have gone on to hold senior positions in state and national public health agencies, unfortunately most did not remain in Florida following their training. While there has been no formal assessment of why EIS officers leave, the limited ability to easily transfer career service from a federal to state agency may be a barrier. Personal factors, such as geographic proximity to family and spousal employment, also may play a role. However, the FDOH BOE has a number of epidemiologists who are graduates of the CDC EIS program. Currently, this includes the State Epidemiologist, a CDC Field Officer assigned to FDOH, and the Administrator of the Acute Disease Section.

In addition to support at their local assignments, fellows are well supported by expertise throughout the state DOH. Shortly after starting the program, fellows spend a week at DOH where they meet with representatives from the various divisions and bureaus including Environmental Health, Maternal and Child Health, Office of Injury Prevention, Public Health Preparedness, and programs within the BOE including acute disease, surveillance, and chronic disease. The goal of these meetings is to provide introductions, familiarize fellows with the various program areas, and make available opportunities to discuss areas of mutual interest and collaboration on future projects.

The didactic component of the training includes both group and individual education. Typically, required didactic training is scheduled on a quarterly basis throughout the program in various locations throughout the state, and all fellows are expected to attend. Courses incorporate learning objectives for each activity. While outcomes are not specifically measured, much of the training involves interactive participation where skill acquisition can be readily observed. For example, this includes but is not limited to training in laboratory methodology and procedures, media training, tabletop exercises, training in software such as Geographical Information Systems mapping, introduction to Institutional Review Board procedures, grant writing, and writing for publication. Specialized trainings in areas of interest are approved on an individual basis. Additionally, fellows collaboratively participate in a group research project each year that includes one to two weeks in the field. Projects have included injury/mortality (beach drownings due to rip currents), prevention (sun safety and skin cancer prevention), and environmental epidemiology (harmful algal blooms).

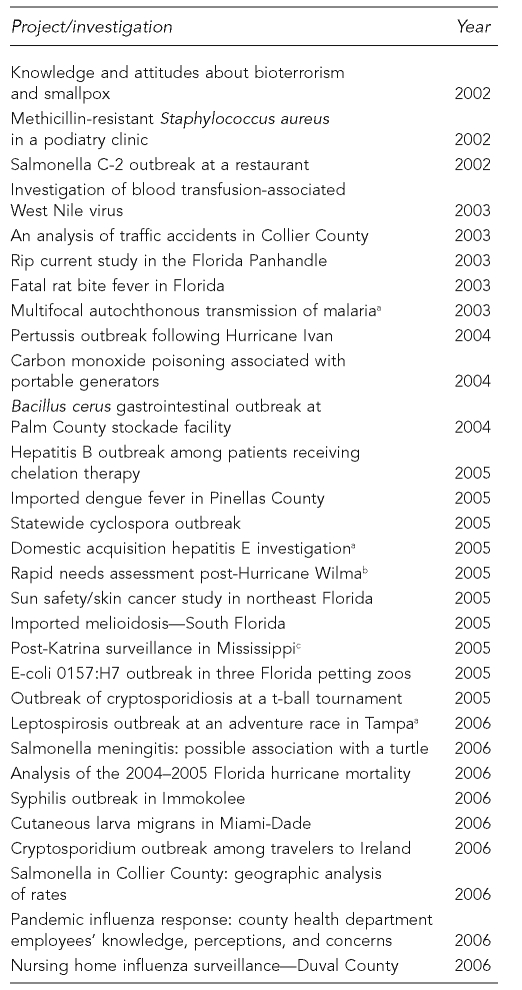

As evidenced by the selected projects and investigations in which FL-EIS has participated (Figure 1), the geographic, cultural, and economic diversity in Florida provides a unique and rich learning environment and ample opportunity for generating presentations and publications.

Figure 1.

Selected projects and investigations of the Florida Epidemic Intelligence Service

As part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Epi-Aid Investigation

In conjunction with CDC/North Carolina Department of Health

Part of multistate, multiagency deployment

Funding

The program is funded, in part, through the Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreement, with state general revenue providing the remainder. Designated funds cover the program director and fellow salaries and standard state employee benefits, and provide allocations for travel funding to professional meetings and educational support. Laptops, wireless handheld devices, and other field equipment also are provided to each fellow. Using emergency preparedness funds to create a program to build epidemiologic capacity, rather than simply to purchase supplies and provide in-service training, will provide a significant and long-lasting impact.

Leadership

Program administration includes a program manager supported by an administrative assistant. Administrators have all held doctoral degrees, either clinical (medical degree/Doctor of Osteopathy [DO]) or academic (Doctor of Philosophy [PhD]/Doctor of Public Health), and have had specific training and experience in public health epidemiology (applied epidemiology fellowship and/or Master of Public Health [MPH] degree). Each fellow also is assigned a primary mentor/supervisor at his/her local county health department/consortium, and may also have secondary mentors/supervisors.

Preceptors

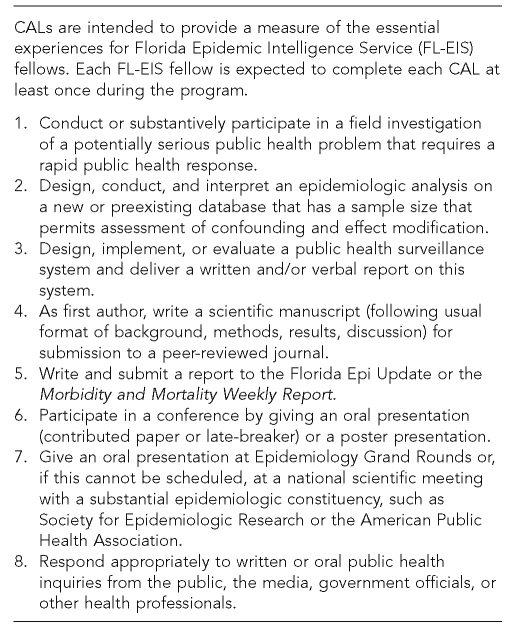

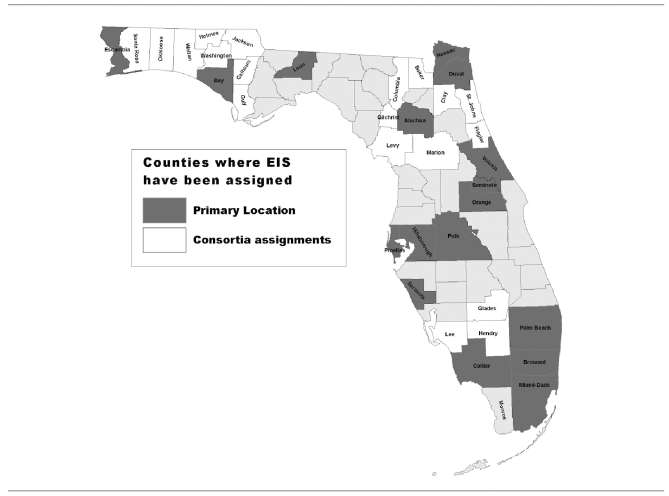

Host sites are selected by a competitive proposal process. Proposals are solicited from individual and consortias of county health department(s) to host an FL-EIS fellow for a period of two years. Smaller capacity county health departments that may not have the resources to host a fellow often partner with other nearby counties to create a comprehensive host site proposal. The site is expected to provide a stimulating learning environment in which the fellow will have not only a supervisor experienced in epidemiology, but one who can serve as a role model and mentor and will work with the BOE staff, who will serve as co-preceptors. Preceptor backgrounds are diverse and have included physician county health department directors, doctoral- and master's-level prepared epidemiology program supervisors and epidemiologists, and other clinicians (physicians, advanced registered nurse practitioners) with epidemiology training. In addition to the list of Core Activities for Learning (CALs) (Figure 2), which each assignee must complete during the fellowship, there must be a well-defined epidemiologic project identified to work on upon arrival. Host sites also are expected to provide adequate office space, computer support, and travel to professional meetings. Assignees are matched with preceptors following “match day” interviews approximately one month prior to assignment. Counties not selected as host sites can still request the assistance of FL-EIS fellows as needed for outbreaks or special projects. A map of counties that have hosted FL-EIS fellows can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Florida Epidemic Intelligence Service required Core Activities for Learning (CALs)

Figure 3.

Florida Epidemic Intelligence Service fellow county assignments: primary and consortia counties

Applicants

Requirements to apply for FL-EIS include a master's or doctoral degree in a health-related field, completion of at least one graduate-level course each in epidemiology and biostatistics, and/or people with significant work experience in public health and a demonstrated interest in practicing epidemiology in Florida. All applicants also must complete a personal statement and a State of Florida application for employment, and provide current curriculum vitae, transcripts, and three letters of reference. The application process opens in December each year and closes in mid-March the following year.

As evidenced by the number of applications received each year, there is growing interest in applied epidemiology training. For 2005 and 2006, the number of applications ranged from 125 to 140 for the six positions available. Applicants ranged from recent graduates with degrees in public health to experienced health professionals with an interest in epidemiology. On average, 80% to 90% of those with complete application packages met the minimum qualifications of the program. Of these, the 20 to 25 most competitive applicants were invited to participate in telephone screening interviews. From this group, 10 to 12 applicants were selected for in-person interviews. While applicants were not required to express an interest in working in Florida after graduation, evidence of personal or professional ties or an interest in staying in Florida were viewed favorably. Of the top candidates to whom seats were offered, most accepted the positions unless they determined that another position was a better fit for them. Remaining seats were filled with alternate candidates.

Matriculants

Of the 31 matriculants to date, 77% (n=24) held an MPH as their highest degree at entry, while 16% held other master's degrees, such as Master of Science, Master of Science in Public Health, and Master of Philosophy. Two matriculants (7%) entered with a terminal degree (PhD) and an MPH. Among all matriculants, 68% (n=21) had degrees with a major in epidemiology. Other majors included environmental health, health behavior, communicable disease and tropical health, microbiology, global health, maternal child health, and health policy and management.

Evaluation

To ensure that each fellow is making satisfactory progress through the program, a number of assessment measures are in place. Fellows are expected to submit monthly activity reports, reviewed by their local preceptor and the program administrator, that summarize their activities for the month, demonstrate progress with ongoing projects, and outline plans for the upcoming month. Sample work products such as outbreak reports, PowerPoint presentations, and draft manuscripts are attached to allow ongoing review and feedback. Additionally, any presentation or publication with more than a local venue audience requires “scientific clearance” by a physician epidemiologist at the BOE. Similarly, cumulative activity reports are submitted every six months to provide continual monitoring to ensure that CALs are being achieved.

On a quarterly basis, fellows are evaluated by local preceptors on performance of competencies in epidemiologic process, communication, and professionalism. Fellows also provide feedback on their preceptors and assignments at this time. Additionally, the program administrator makes periodic site visits to health departments to visit with fellows, their preceptors, and other colleagues with whom they work. While there is not a formal policy, successful program completion is based on a global assessment of the fellow as evidenced through satisfactory completion of the CALs, and progressive professional development as demonstrated on evaluations conducted throughout the experience. The continual monitoring and feedback ensures that most fellows easily achieve their CALs, although the submission of a first-authored scientific manuscript may still be in progress at the time of graduation. Program graduates are awarded a certificate.

Program outcomes: graduates and employment

To date, 95% (18/19 people) of the first three entering classes have completed the program. Attrition for matriculants (n=31) in the first five years of the program has been minimal, with only one individual leaving prior to program completion. Graduate outcome data were obtained by a survey administered among graduates in October 2006 (response rate = 18/18, or 100%) and through personal communication.

Among program graduates who are employed as epidemiologists, 100% (15) are employed as epidemiologists for local or state health departments. Two other program graduates (11%) are pursuing additional professional degrees (DO, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine) and one graduate is currently not working. Graduates have held an average of 1.1 epidemiology positions since program completion.

Graduate retention has been excellent. Twelve graduates (67%) are employed as epidemiologists in Florida. Of these, five are employed at FDOH (42%) and seven at county health departments (58%). Among the latter, all are employed at the sites where they completed their fellowship (39% of all graduates). Three graduates work in other states, including California, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. Their employers include a binational office of border health, a state health department, and a county health department.

Among the 15 graduates currently working as epidemiologists, 11 (73%) report that their primary program area is infectious disease, three (20%) work in bioterrorism/emergency preparedness, and one (7%) is employed in injury prevention. Specific job titles are diverse and include, but are not limited to, environmental epidemiologist, injury epidemiologist, syndromic surveillance epidemiologist, human arbovirus infections coordinator and epidemiologist, senior epidemiologist, respiratory diseases epidemiologist, and surveillance and reporting administrator. Of this group, seven (47%) supervise support staff, other epidemiologists, or both, while eight (53%) do not supervise personnel in their current positions.

Seven of the graduates currently employed as epidemiologists (47%) also report serving as a guest lecturer at a college or university or have an adjunct academic appointment as faculty or coordinator. Two have completed a public health leadership institute program.

DISCUSSION

Modeled after other AETPs, such as the CDC EIS and Cal-EIS programs, the FL-EIS program aims to increase the capacity of FDOH and the local county health departments to strengthen their epidemiologic capacity to respond to new challenges in disease control and prevention. Although it is still a relatively young program, based on the first three graduating classes, it is meeting its goal of training skilled applied epidemiologists, a significant proportion of which are employed in Florida. Notably, more than one-third of graduates are employed in the county health department to which they were assigned for their fellowship training. Thus, selecting fellows with a demonstrated interest in practicing epidemiology in Florida at the time of application and having mentorship through experienced epidemiologists in both the assigned county health department and at the (state) DOH may be key factors in retaining graduates.

The FL-EIS program also faces future challenges. Along with all agencies delivering public health services and training that rely on increasingly limited funding availability, the program will need to be able to demonstrate continued accountability and successful outcomes. In particular, the program needs to be able to ensure that graduates are competent and are meeting evolving workforce needs. As such, a comprehensive program assessment is planned to identify areas that can be strengthened and to plan for future direction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D'Juan Harris, MSP, Geographical Information Systems Specialist, for the development of Figure 3.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thacker SB, Dannenberg AL, Hamilton DH. Epidemic Intelligence Service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 50 years of training and service in applied epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:985–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koplan JP, Thacker SB. Fifty years of epidemiology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: significant and consequential. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:982–4. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White ME, McDonnell SM, Werker DH, Cardenas VM, Thacker SB. Partnerships in international applied epidemiology training and service: 1975–2001. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:993–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moolenaar RL, Thacker SB. Evaluation of field training in the Epidemic Intelligence Service—publications and job choices. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network. [cited 2006 Oct 19]. Available from: URL: http://www.tephinet.org/index.php.

- 6.California Department of Health Services. California Epidemiologic Investigation Service (Cal-EIS) training program. [cited 2006 Jul 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.dhs.ca.gov/ps/cdic/cdcb/pds/CALEIS/index.htm.

- 7.Gewin V. Epidemiology: the spread of epidemiology. [cited 2006 Aug 7];Nature. 2003 423:784–5. Also available from: URL: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v423/n6941/full/nj6941-784a.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florida Department of Health. Florida Epidemic Intelligence Service program. [cited 2006 Jul 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.doh.state.fl.us/disease_ctrl/epi/FLEIS/fleis.htm.

- 9.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. CSTE/CDC applied epidemiology fellowship program. [cited 2006 Jul 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.cste.org/Workforcedev/main1.htm.

- 10.Assessment of the epidemiologic capacity in the state and territorial health departments, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(43):1049–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assessment of epidemiologic capacity in state and territorial health departments—United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(18):457–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) and Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Preface to applied epidemiology competencies. [cited 2006 Jul 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.cste.org/Assessment/competencies/FINALAcceptedPrefacetoAEC061906.pdf.

- 13.Thacker SB, Goodman RA, Dicker RC. Training and service in public health practice, 1951–90—CDC's Epidemic Intelligence Service. Public Health Rep. 1990;105:599–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healthy People 2010 objectives. [cited 2006 Aug 30]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/default.htm.