Abstract

The ability of membrane voltage to activate high conductance, calcium-activated (BK-type) K+ channels is enhanced by cytosolic calcium (Ca2+). Activation is sensitive to a range of [Ca2+] that spans over four orders of magnitude. Here, we examine the activation of BK channels resulting from expression of cloned mouse Slo1 α subunits at [Ca2+] and [Mg2+] up to 100 mM. The half-activation voltage (V0.5) is steeply dependent on [Ca2+] in the micromolar range, but shows a tendency towards saturation over the range of 60–300 μM Ca2+. As [Ca2+] is increased to millimolar levels, the V0.5 is strongly shifted again to more negative potentials. When channels are activated by 300 μM Ca2+, further addition of either mM Ca2+ or mM Mg2+ produces similar negative shifts in steady-state activation. Millimolar Mg2+ also produces shifts of similar magnitude in the complete absence of Ca2+. The ability of millimolar concentrations of divalent cations to shift activation is primarily correlated with a slowing of BK current deactivation. At voltages where millimolar elevations in [Ca2+] increase activation rates, addition of 10 mM Mg2+ to 0 Ca2+ produces little effect on activation time course, while markedly slowing deactivation. This suggests that Mg2+ does not participate in Ca2+-dependent steps that influence current activation rate. We conclude that millimolar Mg2+ and Ca2+ concentrations interact with low affinity, relatively nonselective divalent cation binding sites that are distinct from higher affinity, Ca2+-selective binding sites that increase current activation rates. A symmetrical model with four independent higher affinity Ca2+ binding steps, four voltage sensors, and four independent lower affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ binding steps describes well the behavior of G-V curves over a range of Ca2+ and Mg2+. The ability of a broad range of [Ca2+] to produce shifts in activation of Slo1 conductance can, therefore, be accounted for by multiple types of divalent cation binding sites.

Keywords: K1 channels, Ca21- and voltage-gated K1 channels, Slo1 channels, stochastic models, channel kinetics

INTRODUCTION

Most ion channels open in response to a change in a single, primary physiological parameter. In contrast, activation of Ca2+- and voltage-dependent large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels is complicated by the fact that two parameters govern channel opening. Membrane depolarization and binding of Ca2+ ions interact in some way to bring about an increase in channel open probability. The dependence on Ca2+ is particularly remarkable in that the ability of voltage to open BK channels can be shifted by over four log orders of [Ca2+] (Moczydlowski and Latorre 1983; Meera et al. 1996; Cox et al. 1997a; Cui et al. 1997). Although the voltage dependence of BK channel gating is thought to arise from a mechanism involving voltage-sensing residues in the S4 segment (Diaz et al. 1998; Horrigan et al. 1999; Horrigan and Aldrich 1999; Cui and Aldrich 2000), which is similar to the voltage-dependent K+ channel family, the precise mechanism by which Ca2+ exerts its effects remain unknown. Some of the effects of Ca2+ may be mediated by interaction of Ca2+ with a patch of negatively charged residues, termed the “Ca2+ bowl,” located just before the S10 hydrophobic segment near the COOH terminus of the Slo α subunit (Schreiber and Salkoff 1997; Schreiber et al. 1999). Residues just upstream of the Ca2+ bowl may also participate in defining the Ca2+-regulatory domain (Braun and Sy 2001). However, how this Ca2+-sensing domain may mediate its effects remains unknown. Moreover, there are several studies that indicate that Ca2+ and/or other divalent cations may also allosterically modulate BK gating (Golowasch et al. 1986; Oberhauser et al. 1988; Solaro et al. 1995; Shi and Cui 2001a).

The relationship between V0.5 and cytosolic Ca2+ has provided a convenient descriptive tool to evaluate the Ca2+ dependence of activation of BK current, an approach first employed by Moczydlowski and Latorre 1983. In this landmark paper (Moczydlowski and Latorre 1983), the probability of being open of single skeletal muscle BK channels as a function of Ca2+ and voltage was examined in bilayers. Over [Ca2+] from near 1 μM to almost 10 mM, the V0.5 varied as an essentially linear function of pCa, leading them to propose that Ca2+ binding, per se, is the voltage-dependent step in BK channel activation. More recently, a number of labs have investigated the Ca2+ dependence of activation of cloned α subunits encoding BK-type channels using primarily macroscopic current measurements (Wei et al. 1994; Meera et al. 1996; Cox et al. 1997a) and found that the relationship between V0.5 and pCa may not be quite so simple. Most notably, over a range of [Ca2+] from near 0.5 nM to ∼50 nM, currents resulting from expression of cloned subunits appear to be fully activated with sufficiently high voltage, but in a Ca2+-independent fashion (Cui et al. 1997; Horrigan et al. 1999). Furthermore, the G-V curve for activation and the time constant of current activation remains relatively insensitive to Ca2+ over the range of 5 to ∼50 nM Ca2+ (Cui et al. 1997). However, over the range of Ca2+ from ∼0.5 to ∼100 μM, V0.5 shifts to more negative potentials, before beginning to exhibit some saturation from ∼100 μM to 1 mM (Wei et al. 1994; Cox et al. 1997a; Cui et al. 1997). The extent of this saturation appears to exhibit some variability among work from different labs or even within the same lab (Wei et al. 1994; Meera et al. 1996; Cox et al. 1997a; Cui et al. 1997; Wallner et al. 1999), although the reasons for this remain unclear. To account for the Ca2+ dependence of the shift in G-V curves, activation models involving separate and independent Ca2+ binding and voltage-dependent steps have proven useful (Cox et al. 1997a; Horrigan et al. 1999; Rothberg and Magleby 1999; Cox and Aldrich 2000; Cui and Aldrich 2000). However, an additional feature of activation of cloned BK channels (Wei et al. 1994; Solaro et al. 1995; Meera et al. 1996) and native BK channels (Moczydlowski and Latorre 1983) is that, as Ca2+ is raised above 1 mM, there appears to be an additional shift in the V0.5, which is inconsistent with most current models of Ca2+ dependence of BK activation. As yet, these effects of mM concentrations of Ca2+ are not understood.

In addition to its ability to shift gating over such a broad concentration range, one of the remarkable characteristics of the ability of Ca2+ to promote activation of BK channels is its high selectivity over other divalent cations. In particular, although both Sr2+ and Mn2+ can activate BK channels in the absence of Ca2+, they are relatively ineffective compared with Ca2+ (Oberhauser et al. 1988). Other divalent cations such as Mg2+, Ni2+, and Pb2+ are ineffective at opening BK channels effects (Oberhauser et al. 1988), although Mg2+ and Ni2+, but not Pb2+, enhance activation of channels already activated by Ca2+ (Golowasch et al. 1986; Oberhauser et al. 1988). The enhancement of activation involves an increase in the apparent Hill coefficient for activation by Ca2+ (Golowasch et al. 1986; Oberhauser et al. 1988). Together, these earlier results raise the possibility that multiple kinds of divalent cation binding sites may regulate BK channel gating, thereby perhaps accounting, in part, for the ability of Ca2+ to modulate BK gating over such a wide range of [Ca2+].

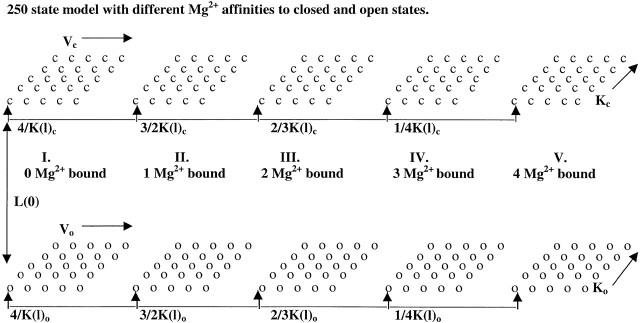

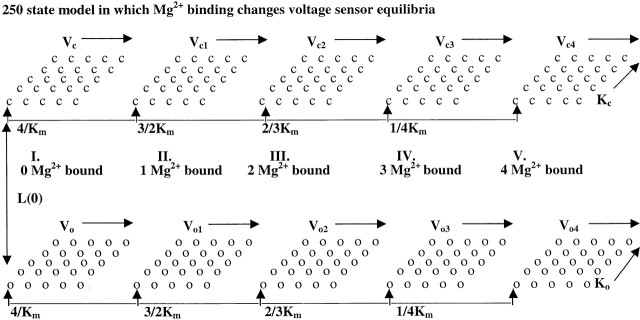

To address these issues, we have examined effects of millimolar [Ca2+] on the gating of currents resulting from expression of the mSlo1 α subunit and compared this with the ability of Mg2+ to alter currents resulting from activation by various concentrations of Ca2+. We show that the enhancement in BK current activation by [Ca2+] of 1 mM and greater or by millimolar Mg2+ added to Ca2+-containing solutions can be accounted for by a low affinity, divalent cation binding site that affects channel activation in a way quite distinct from the effects of μM Ca2+. The enhancement by Mg2+ occurs in the complete absence of Ca2+, which indicates that Mg2+ does not modify Ca2+ binding steps. Furthermore, Mg2+ does not substitute for Ca2+ at the high affinity Ca2+ binding sites. The shifts in gating produced by millimolar Mg2+ do not involve increases in current activation rates, but do involve a slowing of the return to closed states. Thus, qualitatively, millimolar concentrations of divalents appear to enhance BK activation by affecting the closed-to-open channel equilibrium without direct effects on Ca2+ affinities. A similar conclusion has also been drawn in the companion paper by Shi and Cui 2001b. To account for these observations, we propose a simple extension of a specific two-tiered 50-state activation model proposed by Cox and Aldrich 2000. We postulate that, in addition to the regulation of Slo1 gating by four independent high affinity Ca2+ binding steps and independent movement of four voltage sensors, binding of Mg2+ also allosterically regulates Slo1 opening independent of Ca2+ binding and voltage-sensor movement. Such a model accurately reproduces the behavior of G-V curves for Ca2+ from 0 to 100 mM, with Mg2+ from 1 to 100 mM. The analysis suggests that, although Mg2+ and Ca2+ appear to have similar effects at millimolar concentrations, the affinities of Ca2+ to the low affinity sites on open and closed channels are about seven- to eightfold greater than the affinities of Mg2+, which indicates that under physiological conditions, the low affinity sites may participate in the regulation of BK channel gating. The success of this model is improved by taking into account the proposal that millimolar Mg2+ acts not only to promote activation through the low affinity site, but also to inhibit Ca2+ binding at the high affinity Ca2+ binding site (see Shi and Cui 2001b, in this issue).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oocyte Removal and Culture

Mature stage IV Xenopus laevis oocytes were prepared for injection as described in previous work (Wei et al. 1994; Xia et al. 1999; Lingle et al. 2001; Zeng et al. 2001).

Constructs

The mSlo1 (Butler et al. 1993) construct used in initial experiments was provided by L. Salkoff (Washington University) and is identical to that used in earlier work (Wei et al. 1994). In more recent experiments, mSlo1 was placed in an alternative vector (Xia et al. 1999). No differences in physiological properties have been observed between the two constructs.

Recording Pipettes

Patch-clamp recording pipettes were made by pulling borosilicate capillary tubes (Drummond Microcaps; 100 μl) to a tip diameter of ∼1 μM. Pipette resistances (Rp) measured in recording salines ranged from 1.5 to 10 MΩ for single-channel recordings and from 1.5 to 3 MΩ for macroscopic currents. Because of the large currents obtained with Slo1 expression, the series resistance (Rs) associated with the pipette may result in nominal voltage values that are different from the true applied voltage. In most experiments, we only used patches in which the maximal current at +100 mV was ∼5 nA or less. Although larger currents were typically associated with pipettes of smaller Rp, in the worst cases currents may still result in a voltage errors of 5–15 mV. However, close examination of the G-V curves from individual patches used to generate the averaged G-V curves of Fig. 2 B does not reveal any systematic correlation of V0.5 with current density at any [Ca2+]. All voltage values reported here have been uncorrected for possible series resistance errors.

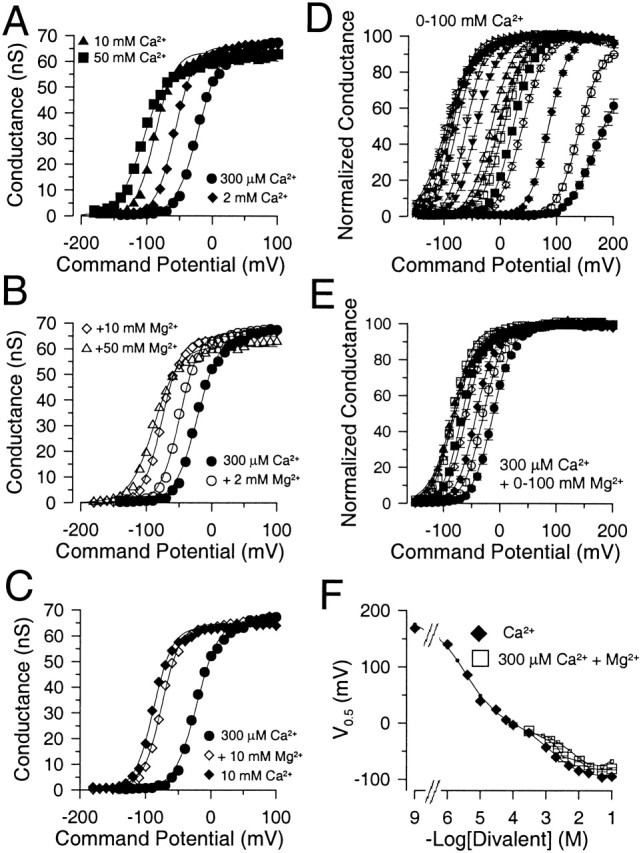

Figure 2.

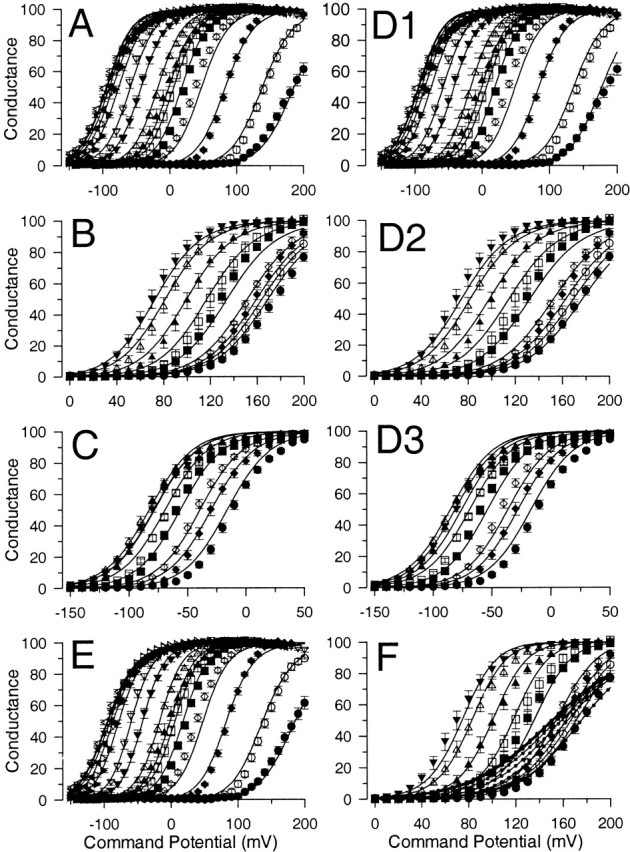

High concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ are similarly effective at shifting current activation. In A, G-V curves were generated from tail currents obtained with 300 μM, 2 mM, 10 mM and 50 mM Ca2+ (patch in Fig. 1). Solid lines are fits of , with values for V0.5 of −21.5 ± 1.0 mV (k = 17.1 mV), −57.1 ± 0.7 mV (k = 14.6 mV), −87.5 ± 0.7 mV (k = 14.4 mV) and −104.5 ± 1.1 mV (k = 19.0 mV), for 300 μM–50 mM Ca2+, respectively. In B, G-V curves from the same patch as in A are shown for currents obtained with 300 μM Ca2+, and 300 μM Ca2+ with either 2, 10, or 50 mM added Mg2+. Values for V0.5 for 2, 10, and 50 mM Mg2+ containing solutions were as follows:−48.7 ± 1.0 mV (k = 14.8 mV), −75.5 ± 0.8 mV (k = 14.5 mV), and −87.4 ± 1.1 mV (k = 18.7 mV), respectively. In C, G-V curves are shown for 300 μM Ca2+, 20 mM Ca2+, and 300 μM Ca2+ + 20 mM Mg2+. In D, the mean conductance measured as a function of voltage is displayed for a set of patches over a range of Ca2+ concentrations from 0 to 100 mM. Solid lines are fits of . For 0 Ca2+ (•), V0.5 = 168.5 ± 2.2 mV, k = 22.4 ± 1.0 mV; for 1 μM Ca2+ (○), V0.5 = 136.89 ± 0.9 mV, k = 18.8 ± 0.7 mV; for 4 μM (♦), V0.5 = 85.2 ± 0.6 mV, k = 16.9 ± 0.5 mV; for 10 μM (⋄), V0.5 = 39.0 ± 0.5 mV, k = 19.1 ± 0.5 mV; for 30 μM (▪), V0.5 = 22.4 ± 0.5 mV, k = 17.9 ± 0.4 mV; for 60 μM (□), V0.5 = 5.8 ± 0.8 mV, k = 19.3 ± 0.5 mV; for 100 μM (▴), V0.5 = −2.4 ± 0.7 mV, k = 21.2 ± 0.5 mV; for 300 μM (▵), V0.5 = −15.9 ± 0.6 mV, k = 18.9 ± 0.5 mV; for 1 mM (▾), V0.5 = −42.4 ± 0.6, k = 18.4 ± 0.5 mV; for 2 mM (▿), V0.5 = −60.5 ± 0.6 mV, k = 15.6 ± 0.5 mV; for 5 mM (▸), V0.5 = −77.6 ± 0.8 mV, k = 16.9 ± 0.7 mV; for 10 mM (▹), V0.5 = −85.2 ± 0.8 mV, k = 16.5 ± 0.7 mV; for 20 mM (◂), V0.5 = −89.3 ± 0.8 mV, k = 19.0 ± 0.7 mV; for 50 mM (◃), V0.5 = −97.9 + 1.1 mV, k = 22.2 ± 0.9 mV; and for 100 mM (★), V0.5 = −93.5 ± 0.9 mV, k = 22.5 ± 0.8 mV. Each point represents the mean with SD of from 4 to 12 patches. In E, G-V curves were generated from a set of patches (mean and SD for 4–19 patches) with 300 μM Ca2+ with various Mg2+ concentrations. Solid lines are fits of . For 300 μM (•), V0.5 = −11.6 ± 0.5 and k = 17.8 ± 0.5 mV; with 1 mM Mg2+ (○), V0.5 = −28.5 ± 0.7 mV, k = 17.4 ± 0.6 mV; with 2 mM Mg2+ (♦), V0.5 = −41.4 ± 0.6 mV, k = 17.1 ± 0.5 mV; with 5 mM Mg2+ (⋄), V0.5 = −58.4 ± 0.6 mV, k = 16.9 ± 0.6 mV; with 10 mM Mg2+ (▪), V0.5 = −67.1 ± 0.7 mV, k = 16.5 ± 0.6 mV; with 20 mM Mg2+ (□), V0.5 = −82.6 ± 0.8 mV, k = 16.8 ± 0.7 mV; with 50 mM Mg2+ (▴), V0.5 = −82.8 ± 1.4 mV, k = 21.6 ± 1.3 mV; and 100 mM Mg2+ (▵), V0.5 = −79.6 ± 1.3 mV, k = 21.3 ± 1.1 mV. In F, V0.5 values measured in D and E are plotted as a function of the indicated divalent cation concentration for either solutions with Ca2+ alone (♦) or for 300 μM Ca2+ with added Mg2+ (□). The 5 mM EGTA, 0 Ca2+ solution was plotted as 10−9 M. Solid lines with small filled circles (Ca2+ alone) and small open squares (300 μM Ca2+ plus Δ[Mg2+]) represents expectations derived from a fit of Fig. 1 (values from Table , column D) to the G-V curves in Fig. 2 D.

Pipette tips and shanks were coated with a silicone elastomer (Sylgard 184; Dow Chemical Corp.) and firepolished. A pipette was then filled with an appropriate recording saline and placed over a chloridized silver wire attached to the recording headstage. For some experiments, the reference electrode was a silver chloride pellet immersed in 3M KCl which, in turn, was connected to the recording dish by a KCl-agar bridge (4% agar in 3M KCl). In other experiments, a silver chloride pellet alone was used.

Electrophysiology

Calcium- and voltage-activated potassium channel currents were recorded in the inside-out configuration according to standard procedures (Hamill et al. 1981) using an Axopatch 1C amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc.) with a 50-GΩ feedback resistor and the Clampex program from the pClamp software package (Axon Instruments, Inc.). Currents were recorded in patches pulled from oocytes 1–9 d after injection with cRNAs. Patches used to construct conductance/voltage relationships typically contained large numbers (>50) of Slo1 channels. The room temperature for these experiments was ∼23°C.

Gigaohm seals were formed on oocytes bathed in normal frog Ringer's solution ([in mM] 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4) and, after excision, were transferred to test solutions containing calcium. Pipette/extracellular solution was (in mM) 140 potassium methanesulfonate, 20 KOH, 10 HEPES, and 2 MgCl2, pH 7.0. Test solutions bathing the cytoplasmic face of the patch membrane contained (in mM): 140 potassium methanesulfonate, 20 KOH, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.0 and one of the following: 5 EGTA, for nominally 0 Ca2+ and for 1 μM Ca2+ solutions; 5 HEDTA for 4 and 10 μM Ca2+; or no added Ca2+ buffer for solutions of 30 μM Ca2+ and higher. In earlier experiments (Solaro et al. 1995), solutions were calibrated (93-20 Ca2+ sensor; Orion) against chloride-based solutions in which free Ca2+ was determined using the EGTAETC computer program (E. McCleskey, Vollum Institute). Solutions for more recent experiments were calibrated with commercial Ca2+ calibration solutions (WPI). Comparison of our chloride-based solutions with the commercial standards yielded similar estimates of Ca2+ concentrations.

Mixed Ca2+/Mg2+ solutions were prepared as follows. A 2-M MgCl2 stock solution (crystalline MgCl2; Puratronic, 99.999%; Alfa-Aesar; <0.001% Ca2+ contamination) was prepared with Chelex (Sigma-Aldrich)-treated distilled H2O. Based on the manufacturer's estimate of the Ca2+ contamination in the original MgCl2 material, the 2- M MgCl2 stock should have contained <20 μM Ca2+, which would contribute negligible amounts of Ca2+ at the dilutions we have used. The concentration of Ca2+ in Chelex-treated KCl-based solutions was below the limits of Ca2+ electrode resolution, but yielded G-V curves from Slo1 channels similar to those obtained with solutions with 0 Ca2+, 5 mM EGTA. For K+-MES–based solutions, we were unable to reduce background Ca2+ with Chelex below 1 μM. Without Chelex treatment, electrode readings indicated that K+-MES solutions with no added Ca2+ typically contained 10–15 μM free Ca2+. For unbuffered Ca2+ solutions (K+-MES) of 30 μM Ca2+ and higher, Mg2+ was simply added to make the appropriate concentration from the 2-M MgCl2 stock solution. For additions of Mg2+ to solutions containing 0 μM Ca2+, 5 mM EGTA, we simply added MgCl2 directly to result in the nominal concentrations of Mg2+ indicated in the results.

Based on published stability constants for EGTA, Mg2+, Ca2+, and H+, we estimated the consequences of this addition using EQCALWIN (Biosoft). If we assume a worst case maximal contaminant [Ca2+] from all sources of 30 μM (K+-MES stock, MgCl2 stock, deionized water), with 5 mM EGTA and 100 mM MgCl2, the calculated free Ca2+ and free Mg2+ is 9.6 nM and 97 mM, respectively. At 10 mM nominal MgCl2, the calculated free Ca2+ and free Mg2+ is 2.71 nM and 8.8 mM, respectively. With no added MgCl2, the calculated free Ca2+ is 2.0 nM. Slo1 currents have been shown to be unaffected by changes in free Ca2+ over the range of 0.5–50 nM (Cui et al. 1997). Thus, the effects observed with 0 Mg2+ are unlikely to result from contamination by Ca2+. In reporting the results, we have used the nominal values for free [Mg2+], corresponding to a maximum error of ∼15% in the actual [Mg2+] at the lower concentrations of Mg2+ (1 mM). These errors do not apply to the unbuffered solutions.

In one set of experiments, unbuffered 0-, 4-, and 10-μM Ca2+ solutions were prepared using KCl (rather then K-MES). For preparation of these solutions, a 1-M KCl stock solution was stirred with Chelex for 2–3 h. Finally, after calibration of the Ca2+-sensitive electrode, aliquots of a 10-mM CaCl2 solution were added until the desired electrode reading was achieved. MgCl2 was subsequently added by dilution from the 2-M Mg2+ stock solution. The properties of a 0-Ca2+ solution prepared in this way and compared with the 0-Ca2+, 5-mM EGTA solutions (as described in Electrophysiology) indicated that the background Ca2+ was in the low nanomolar range. Despite the fact after addition of MgCl2 such a 10-mM Mg2+ solution should contain <1 μM contaminant Ca2+, we were still concerned that the effects of addition of Mg2+ to solutions with low [Ca2+] might result from addition of contaminant Ca2+. However, results indicate that some aspects of the kinetic alterations resulting from addition of Mg2+ are inconsistent with the possibility that the effects are being produced by additional Ca2+. In patches, in which 0-, 4-, and 10-μM unbuffered Ca2+ solutions were examined, control solutions with buffered 0, 4 and 10 μM Ca2+ were also examined to ensure that solutions with similar concentrations yielded similar results. The similarity of the G-V curves obtained with both buffered and unbuffered Ca2+ suggests that intrinsic Ca2+ buffering associated with components of the excised patch are minimal. EQCALWIN also was used to calculate expected free Mg2+ and free Ca2+ in ATP-containing solutions using published stability constants (Martell and Smith 1975).

For these experiments, we frequently used divalent cation concentrations up to 100 mM Mg2+ or Ca2+. This resulted in solutions with elevated osmolarity compared with the usual solutions containing 1 mM or lower Ca2+. Such solutions also contain elevated Cl−. We were concerned that these factors might, therefore, influence the conductance-voltage curves, which is independent of the divalent cation concentrations. Several control experiments were done. First, the effect of adding Mg2+ as either MgCl2 or MgSO4 was compared and found to be identical. Second, we prepared 300-μM Ca2+ solutions with added 150 mM N-methylglucamine (NMG) and found that for a set of four patches, G-V curves were identical for 300 μM Ca2+ either with (V0.5 = −23.1 ± 3.2 mV) or without (V0.5 = −20.5 ± 5.6 mV) NMG. Thus, the increase in osmolarity and ionic strength resulting from the addition of NMG does not have a substantial effect on G-V curves activated by 300 μM Ca2+. Similarly, current activation time constants were identical in the two cases. However, with 150 mM NMG, there was a weak voltage-dependent reduction in outward current, perhaps reflecting a weak, rapid blocking effect of NMG on the channel.

Solution Exchange

Solution exchange and drug applications were accomplished with a multibarrel solution delivery system as used previously described (Wei et al. 1994; Herrington et al. 1995; Zeng et al. 2001). In this system, six to seven polyethylene 10 (PE10) tubes were packed into the end of a glass tube that was tapered at one end to an ∼ 50-μm open tip. Solution flowed through one line at all times, and complete solution exchange at the patch membrane required ∼100 ms.

Data Analysis

Analysis of current recordings was done either with Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Inc.) or with programs written in this laboratory. For analysis of patches with one or two channels, leakage subtraction was accomplished by subtracting from the experimental records either an average of records in which no channels opened (either by chance or during perfusion with zero Ca2+ saline) or by subtracting an idealized sweep (using a sweep obtained in 0 Ca2+ as a template) generated to match the experimental leak current. Ensemble averages of BK channel probability of being open (Po) were generated from idealized single-channel current records using a 50% threshold detection algorithm. The single-channel open level was given a value of one and the single-channel closing level was given a value of zero. When the number of channels in the patch (N) is known, average Po can be calculated directly by averaging the idealized records and dividing the average by N. Currents or extracted data were fit using a Levenberg-Marquardt search algorithm to obtain nonlinear least-squares estimates of function parameters.

G-V curves were constructed primarily from tail currents measured 100–200 μs after repolarization and, in some cases, from the peak current measured at a given voltage. Typically, the absolute value of maximal conductance was similar at Ca2+ concentrations between 4 and 300 μM, whereas at lower or higher Ca2+, the observed value for maximal conductance was smaller. In such cases, conductance estimates were normalized to the maximal value observed over the range of 10–300 μM Ca2+. Individual G-V curves were typically fit with a standard Boltzmann function of the following form:

|

1 |

where Gmax is the fitted value for maximal conductance, V0.5 is the voltage of half maximal activation of conductance, and k is the term for the voltage dependence of activation in units of mV.

Fitting of G-V curves to equations defined by particular kinetic models was done with our own software in which a Levenberg-Marquardt optimization routine was used to perform a nonlinear least-squares minimization. To confirm the validity of the implementation of the fitting routine, for any given set of parameter values defined by a given function (e.g., see ), the curves defined by the function were also checked with an implementation of the function in Mathcad (Mathsoft).

RESULTS

Millimolar Concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ Produce Similar Shifts in the Voltage of Half Activation (V0.5).

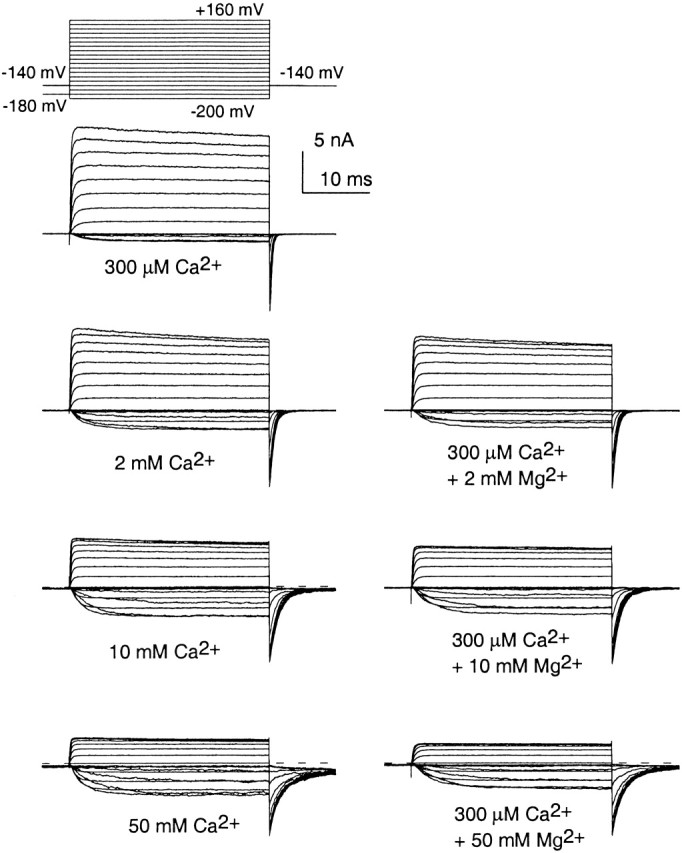

Fig. 1 shows currents from an excised inside-out patch expressing mSlo1 α subunits. On the left, currents were activated with 300 μM, 2 mM, 10 mM, and 50 mM Ca2+. On the right, currents were activated with 300 μM Ca2+ with 2, 10, and 50 mM Mg2+. Qualitatively, it can be seen that the effect produced by increases in [Ca2+] above 300 μM appear to be mimicked by comparable increases in [Mg2+].

Figure 1.

Similar enhancement of Slo1 current activation by high concentrations of either Ca2+ and Mg2+. Each family of traces shows currents from the same inside-out patch from a Xenopus oocyte, expressing mSlo1 α subunits. Currents were activated by the voltage protocol shown on the top left with the indicated divalent cation concentrations applied to the cytosolic face of the patch. On the left, traces were obtained with 300 μM Ca2+, 2 mM Ca2+, 10 mM Ca2+ and 50 mM Ca2+ from top to bottom. On the right, each family of traces was obtained with 300 μM Ca2+ but with added 2, 10, and 50 mM Mg2+ from top to bottom. Tail currents were recorded at −140 mV. For solutions containing 10 and 50 mM divalent, the potential before the activation steps (−200 to +160 mV) was −180 mV, and −140 in other cases. Note the strong slowing of deactivation with either Ca2+ and Mg2+, the similar activation of current with additions of mM Ca2+ or Mg2+, and the strong block of current at positive activation potential at higher divalent concentrations.

Fig. 2 A shows corresponding conductance-voltage relationships (G-Vs) determined from measurements of tail current for the four Ca2+ concentrations illustrated in Fig. 1, whereas Fig. 2 B shows the effects of additions of Mg2+ to current activated by 300 μM Ca2+. In Fig. 2 C, G-V curves resulting from 300 μM Ca2+, 10 mM Ca2+ and 300 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+ are directly compared. It can be seen that once current is activated by 300 μM Ca2+, additions of either Ca2+ or Mg2+ are relatively comparable in their ability to shift G-V curves.

High concentrations of Ca2+ also block Slo1 currents. This block is indicated by the voltage-dependent reduction of current at the most positive activation voltages in the presence of 10 and 50 mM Ca2+ (Fig. 1). Mg2+ also produces a similar voltage-dependent reduction of peak current. This reduction in peak macroscopic conductance is almost entirely mediated by fast channel block (Vergara and Latorre 1983; Ferguson 1991), which can be seen in the reduction of single-channel current amplitude with high [Ca2+] (data not shown for Ca2+ [unpublished data], but see results in Fig. 3 with Mg2+ below).

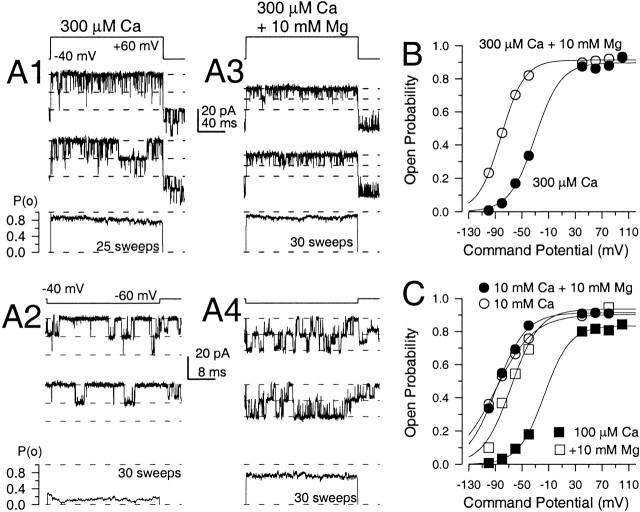

Figure 3.

Millimolar Mg2+ and Ca2+ produce similar shifts to more negative potentials in the relationship between open probability and voltage. In A, traces show currents from an inside-out patch containing two BK channels. Patches were held at −40 mV with repeated voltage steps to either +60 mV (A1 and A3), or −60 mV (A2 and A4). On the left (A1 and A2), channels were activated with 300 μM Ca2+, whereas on the right (A3 and A4) channels were activated with 300 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+. In each panel, the ensemble average expressed in units of probability of being open (Po) is plotted at the bottom. At +60 mV, the addition of Mg2+ has little effect on Po, but reduces the single-channel current amplitude. At −60 mV, Mg2+ produces a substantial increase in Po, with only a mild reduction in the single-channel amplitude. In B, Po estimates obtained from the ensemble averages are plotted as a function of command potential for the patch shown in A. Solid lines are fits of . At 300 μM Ca2+, fitted values with 90% confidence limits were gmax = 0.89 ± 0.02, V0.5 = −30.7 ± 5.1 mV, and k = 19.2 ± 4.4 mV; for 300 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+, gmax = 0.91 ± 0.01, V0.5 = −81.0 ± 1.0 mV, and k = 17.9 ± 1.0 mV. In C, Po versus voltage is plotted for a different patch showing that activation by 10 mM Ca2+ is similar to that produced by 10 mM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+. Fitted values were as follows: for 100 μM Ca2+, gmax = 0.83 ± 0.02, V0.5 = −16.5 ± 4.9 mV, and k = 19.4 ± 2.7 mV; for 100 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+, gmax = 0.94 ± 0.11, V0.5 = −66.2 ± 8.9 mV, and k = 21.3 ± 8.5 mV; for 10 mM Ca2+, gmax = 0.91 ± 0.06, V0.5 = −89.2 ± 5.4 mV, and k = 25 ± 6.9 mV; and for 10 mM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+, gmax = 0.92 ± 0.04, V0.5 = −87.7 ± 3.2 mV, and k = 22.6 ± 3.8 mV.

For a set of patches, the relationship between conductance and activation voltage was determined over Ca2+ concentrations from 1 μM to 100 mM (Fig. 2 D). Similarly, in parallel experiments, the effect of Mg2+ from 1 mM to 100 mM on currents activated by 300 μM Ca2+ was determined (Fig. 2 E). G-V curves were fit with a single Boltzmann () and the relationship between V0.5 and pCa for a large number of patches is plotted in Fig. 2 F. There are two key features. As [Ca2+] is raised to 300 μM, the rate of change in the voltage of half activation appears to slow similar to previous observations (Wei et al. 1994; Cox et al. 1997b; Cui et al. 1997). However, at 10 mM Ca2+, activation is shifted dramatically to more negative potentials by an additional ∼40–50 mV.

Activation of Slo1 by Ca2+ Is Potentiated by Internal Mg2+

The additional leftward shift of activation caused by mM concentrations of Ca2+ coupled with the inflection observed in the V0.5 versus pCa plot raise the possibility that Ca2+ is shifting activation of Slo1 channels through a process distinct from the Ca2+-dependent activation steps that occur at lower [Ca2+]. The fact that, in the presence of 300 μM Ca2+, millimolar Mg2+ and Ca2+ are similarly effective at shifting the V0.5 also supports the idea that effects of mM divalents may involve a different site and mechanism than the gating effects produced by micromolar Ca2+.

It has been shown previously that, in the presence of micromolar Ca2+, millimolar concentrations of internal Mg2+ can potentiate activation of BK channels recorded from rat skeletal muscle transverse tubule membranes (Golowasch et al. 1986; Oberhauser et al. 1988). Because Mg2+ produces minimal channel activation in the absence of Ca2+, it has been proposed that Mg2+ is a positive allosteric modulator of BK channel activity. 400 μM nickel in the presence of 1 μM Ca2+ is also able to shift the V0.5 of this channel by ∼44 mV negative to that measured with 1 μM Ca2+ alone (Oberhauser et al. 1988). Like Mg2+, Ni2+ alone is relatively ineffective at activating BK channels. This suggests that some divalent cations may influence BK gating at a secondary allosteric site. The leftward shift of V0.5 measured for Slo1 with 10 mM Ca2+, then, could be caused by an association of Ca2+ itself with this relatively nonselective site. The experiments presented below address this hypothesis.

Mg2+-induced Shifts in the Single-channel Probability of Being Open Are Similar to Shifts in Macroscopic Currents

Fig. 3 shows that a leftward shift of activation by 10 mM Mg2+ is also evident at the single-channel level. For these experiments, inside-out patches containing one or two channels were stepped repeatedly to particular test potentials. Fig. 3 A shows sample records from a patch containing two channels in which activation is compared at both +60 and −60 mV in the presence of either 300 μM Ca2+ or 300 μM Ca2+ + 10 mM Mg2+. For a given condition, the probability of channels being open (Po) was measured for each sweep and an average Po was generated for a set of sweeps. Fig. 3 B summarizes the average Po determined over a range of voltages from the experiment in Fig. 3 A. Superimposed solid lines are fitted single Boltzmann relations. The plot shows that 10 mM Mg2+ is able to shift activation, as measured by Po, leftward by ∼50 mV. This is similar to the magnitude of the shift measured for macroscopic currents. Both with and without Mg2+, the saturating Po is similar and approaches ∼90%.

Fig. 3 C plots Po estimates as a function of test potential for an experiment similar to that of Fig. 3 A in which channels were activated by either 100 μM Ca2+, 100 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Ca2+ or 10 mM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+. The Po-V relationships for the latter three solutions are all quite similar. This indicates that, in the presence of 100 μM Ca2+, addition of Mg2+ is about as effective as an increase in Ca2+ at producing leftward shifts in the activation curves. In contrast, the further addition of 10 mM Mg2+ to 10 mM Ca2+ is ineffective at producing an additional shift. The V0.5 estimates measured at the single-channel level in the presence and absence of 10 mM Mg2+ are similar to those measured for macroscopic currents.

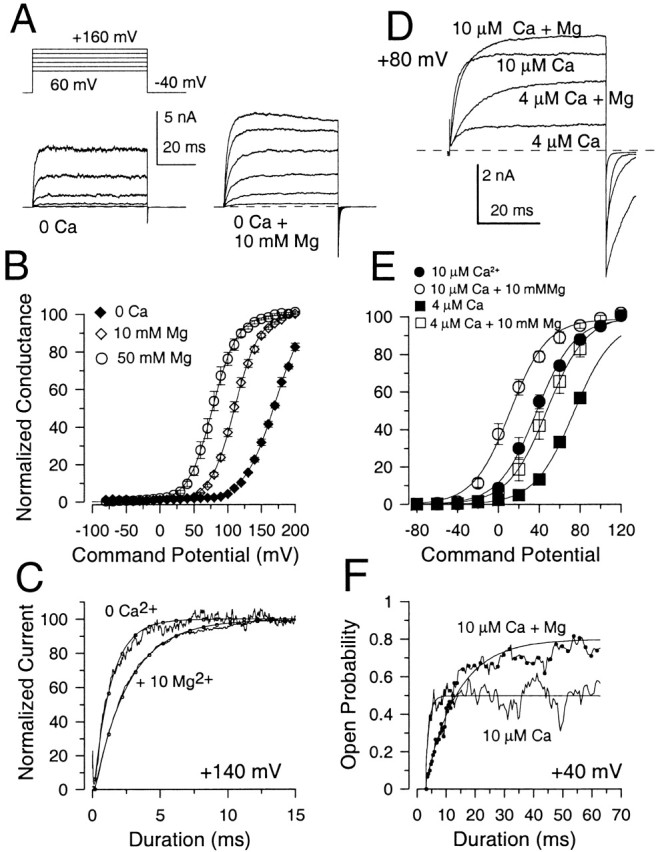

The Magnitude of the Shift in V0.5 Produced by Mg2+ Is Not Ca2+-dependent

We next examined the ability of Mg2+ to shift G-V curves at lower [Ca2+]. Fig. 4 A gives an example of the effect of 10 mM Mg2+ on Slo1 currents activated in the absence of Ca2+. G-V curves (Fig. 4 B) were generated for a set of patches with 0-μM Ca2+ solutions, 0 Ca2+/10 mM Mg2+, and 0 Ca2+/50 mM Mg2+. When 10 mM Mg2+ is added to 0-Ca2+ solutions, conductance begins to be activated ∼50 mV negative to that observed absence of Mg2+, a shift similar to that observed when 10 mM Mg2+ is added to a solution with 300 μM Ca2+. It might be argued that this shift results from the addition of contaminant Ca2+ in the Mg2+ solution. However, as described in the materials and methods, in the solutions with 0 μM Ca2+/10 mM Mg2+/5 mM EGTA, the free [Ca2+] is unlikely to exceed even 10 nM, a concentration that does not activate BK current. Furthermore, the effects of the addition of Mg2+ on current activation time course appear inconsistent with the expected effects of an addition of Ca2+. Although the effects of Ca2+ on activation time course are complex at activation potentials above the voltage of half activation of current, 10 mM Mg2+ produces little effect on the current activation time course (Fig. 9 E), whereas small increases in [Ca2+] typically increase current activation rates. Thus, the effect of Mg2+ appears to differ from what would be expected from the addition of Ca2+. This slowing in activation rate also suggests that the mechanism of Mg2+ action is clearly distinct from the changes in gating that occur with lower concentrations of Ca2+.

Figure 4.

Mg2+ also shifts current activation in lower Ca2+ or 0 Ca2+. In A, currents on the left were activated by the indicated protocol with a solution containing trace Ca2+ with 10 mM EGTA. On the right, currents were activated from the same patch with a solution containing 0 Ca2+, 5 mM EGTA but with 10 mM Mg2+. In 0 Ca2+, time constants of activation (τa) were 1.85, 1.50, 1.12 ms for +120, +140, and +160 mV, respectively. With 10 mM Mg2+, τa was 4.0, 2.72, and 2.22 ms at +120, +140, and +160 mV, respectively. In B, the normalized conductance is plotted as a function of command potential for 0 Ca2+ (eight patches), 10 mM Mg2+ (eight patches) and 50 mM Mg2+ (seven patches). Conductance values were normalized in each patch to the maximum value obtained with 50 mM Mg2+. Fits of (solid lines) yielded values for V0.5 of 170.7 ± 2.6 mV (k = 23.6 mV) for 0 μM Ca2+, 110.5 ± 0.6 mV (k = 18.3 mV) for 10 mM Mg2+, and 78.0 ± 0.5 mV (k = 18.3 mV) for 50 mM Mg2+. In C, currents activated at +140 mV were normalized to peak steady-state amplitude of a single exponential fit to the rising phase of currents activated either with 0 Ca2+ or with 0 Ca2+ + 10 mM Mg2+. The time constant of activation with 0 Ca2+ was 1.50 ms, whereas with 10 mM Mg2+ was 2.72 ms. The slowing of activation with Mg2+ was consistently observed at all activation voltages and argues that the additional activation by Mg2+ is not the result of an increase in trace Ca2+. In D, currents were activated by a voltage step to +80 mV with either 4 or 10 μM Ca2+ without or with the addition of 10 mM Mg2+. Unbuffered divalent cation solutions were prepared as described in the materials and methods. Note the increased current amplitude and slower activation of current in the presence of Mg2+. In E, G-V curves were constructed from measurement of tail currents from a set of 4 patches studied as in D. Error bars represent the SEM of four patches. The V0.5 for each curve is 37.6 ± 1.8 mV (10 μM Ca2+), 11.6 ± 2.5 (10 μM Ca2+ + 10 mM Mg2+), 73.8 ± 1.1 mV (4 μM Ca2+), and 47.8 ± 1.1 mV (4 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+). Buffered Ca2+ solutions prepared at the same time and tested on the same patches yielded V0.5 values of 36.2 ± 1.6 mV for 10 μM Ca2+ and 71.2 ± 1.2 mV for 4 μM Ca2+. In F, ensemble averaged currents were generated from channels activated with the indicated solutions for a voltage-step to +40 mV from a patch containing two channels. The addition of Mg2+ increases the open probability towards maximal values but slows down the time constant of current activation. With 10 μM Ca2+, the activation time constant was 1.4 ± 0.3 ms, whereas with 10 μM Ca2+ plus 10 mM Mg2+ the time constant was 11.1 ± 0.5 ms.

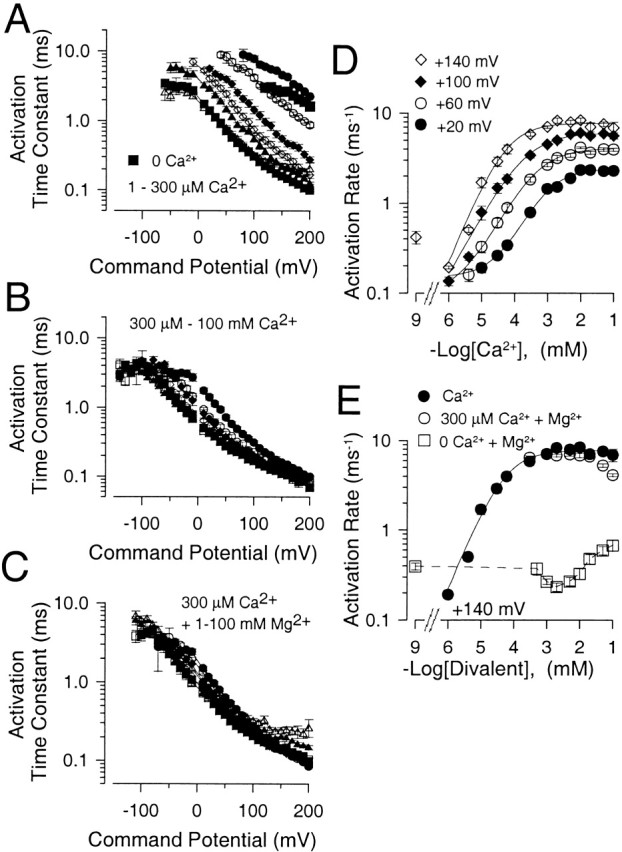

Figure 9.

Millimolar concentrations of either Ca2+ or Mg2+ are similar in their effects on current activation rates. In A, the time constant of activation (τa) is plotted as a function of command potential for Ca2+ concentrations of 1 μM (•), 4 μM (○), 10 μM (♦), 30 μM (⋄), 60 μM (▴), 100 μM (▵), and 300 μM (▪). Error bars in A and B are SEM for 4-13 patches. In B, τa is plotted as a function of command potential for Ca2+ concentrations of 300 μM (•), 1 mM (○), 2 mM (♦), 5 mM (⋄), 10 mM (▪), 20 mM (□), 50 mM (▴), and 100 mM (▵). In C, τa is plotted as a function of command potential for solutions containing 300 μM with added Mg2+ of 0 mM (•), 1 mM (○), 2 mM (♦), 5 mM (⋄), 10 mM (▪), 20 mM (□), 50 mM (▴), and 100 mM (▵). Each point shows the mean and SEM of 4-11 patches. In D, the mean rate of current activation for Slo1 currents is plotted as a function of Ca2+ for command potentials of +20 (•), +60 (○), +100 (♦), and +140 (⋄) mV. Error bars are SEM. Solid lines are fits of . At +20 mV, kmax was 2.4, K d = 0.87 ± 0.30 μM, and n = 0.88 ± 0.28. At +60 mV, kmax was 4.1, K d = 398 ± 160 μM, and n = 0.77 ± 0.20; at +100 mV, kmax = 6.0, K d = 181 ± 59 μM, and n = 0.72 ± 0.14; at +140 mV, kmax = 7.7, K d = 59 ± 25 μM, and n = 0.92 ± 0.32. Note the anomalous slowing of current activation rate at 1 μM Ca2+ relative to 0 μM at +140 mV. This point was not included in the fit. In E, current activation rate is plotted as a function of total divalent in the solution at +140 mV for solutions with no added Mg2+ (•) and solutions with Mg2+ added to 300 μM Ca2+ (○), showing that Mg2+ has little effect on the limiting rate of current activation, although additional depolarization will produce an increase in current activation rate. Note the inhibition of activation rate at the highest [Mg2+]. Current activation with 0 Ca2+ and various [Mg2+] is also plotted (□), showing the relative lack of effect of Mg2+ in comparison to Ca2+.

The ability of Mg2+ to shift activation was also examined with solutions containing either 4 or 10 μM free Ca2+. (Fig. 4, D–F). The shift resulting from 10 mM Mg2+ in this set of four patches was ∼25 mV, less than observed either at 0 or 300 μM Ca2+. An even smaller shift was produced by 10 mM Mg2+ with 10 μM Ca2+ in the experiments of Shi and Cui 2001b. Given that 10 mM Mg2+ appears to produce similar shifts in V0.5 at both 0 Ca2+ and more elevated Ca2+, the smaller effect at intermediate [Ca2+] seems at first glance unusual. Shi and Cui interpreted this smaller shift as the result of an inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on the Ca2+ binding site (see Shi and Cui 2001b, in this issue). Perhaps consistent with this possibility, when Mg2+ was added to solutions with either 4 or 10 μM Ca2+, there was a slowing in the current activation time course (Fig. 4D and Fig. F). Such a slowing might result simply from inhibition by Mg2+ of Ca2+ binding.

The slowing of the activation time course might also be explained by the possibility that Mg2+ was shifting channel activation from a condition of very low open probability to approximately half-maximal open probability. For example, in the simple case of a two-state system,

where τ(V) = 1/(α(V) + β(V)), the slowest τ(V) is achieved when α(V) = β(V). For the effect of Mg2+ on Slo1 currents shown in Fig. 4 D, this possibility seemed unlikely since at 10 μM [Ca2+] and +80 mV, currents should be at least half maximally activated. To verify this directly, the ability of Mg2+ to enhance current activation at a given potential was examined in one or two channel patches in which it was possible to directly define the effect of Mg2+ on single-channel open probability. Such an experiment shown in Fig. 4 F confirms that the slowing of the activation time course even occurs as the open probability goes from about half maximal to near maximal. If Mg2+ produced a shift in V0.5 by simply shifting the effective activation voltage by ∼30–50 mV, an increase in activation rate would have been expected. This is clearly not observed. This leaves us with the possibility that the slowing of activation time course reflects inhibition by Mg2+ of Ca2+ binding, when [Mg2+] sufficiently exceeds [Ca2+].

A Low Affinity, Relatively Nonselective Divalent Cation Binding Site May Account for the Effects of Mg2+ and Ca2+

Fig. 5 A summarizes the ability of Mg2+ to shift V0.5 for currents activated by 300 μM Ca2+ for two separate sets of patches. For both sets of patches, the shift in V0.5 at 100 mM Mg2+ is less than at 50 mM Mg2+. The reduction in shift with 100 mM Mg2+ is the result expected, if Mg2+ inhibits the ability of 300 μM Ca2+ to shift gating. Because of this possible inhibitory action of Mg2+, it is more difficult to ascertain whether the shift in V0.5 produced by Mg2+ exhibits saturation. However, because of the saturation in the shift of V0.5 observed over the range of 20–100 mM Ca2+, it seems likely that the effects of Mg2+ also exhibit a similar saturation. However, it should be noted that both in our experiments and the experiments of Shi and Chi (2001b) additions of Mg2+ over the range of 10–100 mM to 0-Ca2+ solutions do not result in full saturation of the shift in V0.5.

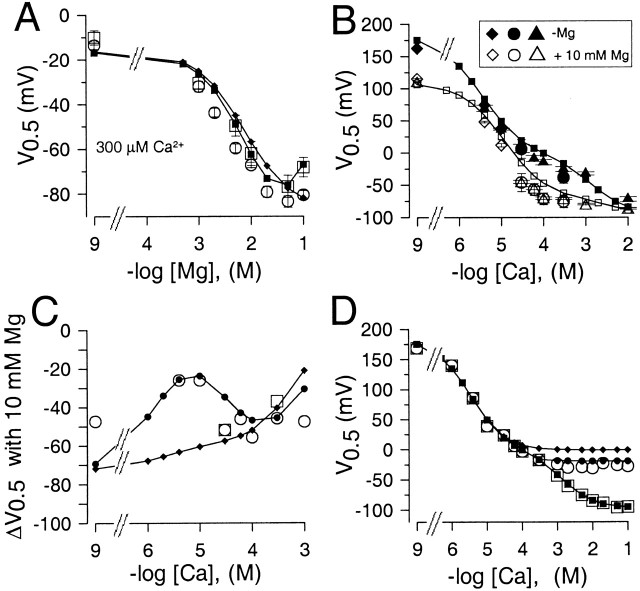

Figure 5.

The ability of mM concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ to shift G-V curves is similar. In A, the V0.5 for activation is plotted as a function of Mg2+ for G-V curves obtained in two separate sets of patches each activated by 300 μM Ca2+ plus the indicated Mg2+. The predictions for the shift in V0.5 as a function of Mg2+ based on two sets of fitted values for Fig. 1 (Table , columns A [♦] and D [▪]) are also displayed. In B, the ability of Mg2+ to shift V0.5 at different Ca2+ is displayed. Triangles show V0.5 values from macroscopic currents without (▴) or with (▵) 10 mM Mg2+. Circles ([•] no Mg2+; [○]: + 10 mM Mg2+) are means and SD for V0.5 determined from Po measurements from four patches with either one or two channels as in Fig. 3. Diamonds ([♦] no Mg2+;[⋄] +10 mM Mg2+) are values obtained with unbuffered Ca2+ solutions. Predictions from the fitted values for Fig. 1 (Table , column D) are also shown for Ca2+ alone (▪) and with 10 mM Mg2+ (□). In C, the change in V0.5 (ΔV0.5) produced by 10 mM Mg2+ at different [Ca2+] is displayed for macroscopic current measurements (○) and single-channel estimates (▪). Estimates of predicted ΔV0.5 based on a fit of Fig. 1 to G-V curves with or without Mg2+ are also shown for two cases: first, Mg2+ inhibition of the high affinity site is allowed (•; Table , column D) and no inhibition by Mg2+ occurs (♦; Table II; column F). In D, values of V0.5 obtained as a function of Ca2+ (□) are replotted along with estimates of the V0.5 corrected at Ca2+ of 1 mM and above by the additional shift produced by Mg2+ shown in A obtained with 300 μM Ca2+. These values (○) provide an indication of the ability of the higher affinity, Ca2+ selective site to shift activation of BK channels, in the absence of the low affinity effect, assuming that the high and low affinity effects are independent and additive. Predicted values for V0.5 based on a fit of Fig. 1 are also shown for the case of both low and high affinity Ca2+ binding sites (▪; Table II; column D), and also for Ca2+ action alone in the absence of a high affinity site (♦). The latter values were also corrected for the approximately −17-mV shift that 300 μM Ca2+ should produce by acting at the low affinity sites (•). The discrepancy between the Mg2+ corrected data and the prediction from Fig. 1 arises from the fact that the Mg2+ correction was obtained with solutions with 300 μM Ca2+ such that the effect of 300 μM Ca2+ on the low affinity site is not taken into account.

Another interesting aspect of the action of Mg2+ is the magnitude of the shift in V0.5 produced by 10 mM Mg2+ at various [Ca2+] up through 10 mM (Fig. 5 B). The results in Fig. 5 B include data from a variety of experimental conditions (Solaro et al. 1995), including estimates of single-channel open probability from one and two channel patches and macroscopic current estimates. Over the range of ∼30 μM–1 mM Ca2+, 10 mM Mg2+ seems to produce a rather constant shift of about −40 to −60 mV. Similarly, the shift at 0 Ca2+ is also about −50 mV. However, when 10 mM Mg2+ is added to 10-mM Ca2+ solutions, the resulting shift is substantially reduced. This latter effect is consistent with the idea that Mg2+ and Ca2+ are competing for a saturable, low affinity binding site. The magnitude of the shift caused by 10 mM Mg2+ over all Ca2+ is summarized in Fig. 5 C. Fig. 5 (B and C) also includes data obtained with unbuffered 4- and 10-μM Ca2+ solutions in which the shifts produced by 10 mM Mg2+ were only about −25 mV, similar to the results of Shi and Cui 2001b. In general, the ability of Mg2+ to shift gating over all [Ca2+] qualitatively supports the idea that, even under conditions where the higher affinity site is only partially occupied by Ca2+, Mg2+ still produced substantial shifts in gating and does so without substituting for Ca2+ at the higher affinity sites.

Because of the possibility that the effect described here may reflect an important regulatory role of free cytosolic Mg2+, we also examined the ability of Mg2+ to shift activation, when Mg is added as MgATP. When Mg2+ is added as 2 mM Mg-ATP, solutions with nominal 100 μM Ca2+ are much less effective at activating current. ATP will bind both Mg2+ and Ca2+. Based on published stability constants (Martell and Smith, 1974), the solution used here (100 μM added Ca2+, 2 mM added MgATP) is calculated to have 33 μM free Ca2+ and 407 μM free Mg2+. The V0.5 observed for the solution containing 2 mM added MgATP (−6.3 ± 1.3 mV) is similar to that which would be expected for a 30-μM Ca2+ solution (about +8 mV) with an additional negative shift of ∼10 mV resulting from 400 μM Mg2+. Thus, the experiment is consistent with the idea that the shift produced by high Mg2+ depends on the free Mg2+ concentration, and that ATP reduces both free Ca2+ and free Mg2+.

The shift caused by increasing [Mg2+] from 1 to 10 mM is ∼45–50 mV, whereas the shift caused by increases in [Ca2+] from 1 to 10 mM is also ∼50 mV. Thus, high concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ may be acting at the same site(s) on the channel protein to modulate BK channel gating, independent of the action of Ca2+ at the higher affinity, Ca2+-specific sites. This implies that there are at least two types of Ca2+ binding sites that are important for channel function. First, there are high affinity, relatively Ca2+-specific sites that, along with depolarization, produce channel opening. Second, there are low affinity sites that can bind either Ca2+ or Mg2+ to potentiate activation of channels, no matter whether channels are activated in the presence or absence of Ca2+.

If we assume that high concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ bind to the same or similar sites and are able to promote activation of Slo1 currents in a similar fashion, then the results in Fig. 5 A can be used to “subtract” the effect of Ca2+ at the putative low affinity site from the V0.5-pCa relationship shown in Fig. 2 E. This manipulation would then reveal the effect of Ca2+ acting only at the putative high affinity sites. This makes the assumption that the effects of high and low affinity sites on V0.5 are independent, an issue which is addressed below. The consequences of this assumption are presented in Fig. 5 D. The open squares are V0.5 values resulting from the action of [Ca2+] reproduced from Fig. 2 E. The additional shift in V0.5 resulting from higher [Ca2+] were then assumed to be equivalent to the additional shift in V0.5 resulting from high [Mg2+]. Therefore, the closed squares were obtained by subtracting the magnitude of the shift of V0.5 caused by a given [Mg2+] in the presence of 300 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 5 A) from the V0.5 measured in the presence of the identical [Ca2+], but without Mg2+. For example, the V0.5 measured at 2 mM Ca2+ was shifted positive by the amount of shift caused by 2 mM Mg2+. Thus, assuming Ca2+ and Mg2+ act equivalently at the same (or similar) binding site(s), the closed squares reflect the action of Ca2+ at the higher affinity sites alone. Once a correction is made for the effect of Ca2+ on low affinity binding sites, it is evident that for [Ca2+] greater than ∼300 μM, the corrected V0.5 's are no longer shifted negative by additional Ca2+, even though activation remains voltage-dependent. This is consistent with the idea that high affinity, Ca2+-dependent steps leading to activation are separate from voltage-dependent steps (Wei et al. 1994; Cox et al. 1997a; Horrigan and Aldrich 1999; Horrigan et al. 1999). Another way of thinking about this is that the relationship between V0.5 and Ca2+ in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ is essentially constant from 100 μM to 100 mM (Fig. 5 B). Thus, the channel is essentially unaffected by changes in [Ca2+] over two orders of magnitude, although gating continues to be controlled by voltage.

Concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ of 1 mM and above Have Minor Effects on Current Activation Rates at Potentials from +40 mV and More Positive

The above results argue that, at Ca2+ or Mg2+ concentrations of 1 mM and above, leftward shifts in the open probability of BK channels result primarily from the action of divalent cations at a relatively nonselective site distinct from higher affinity sites that specifically mediate Ca2+-dependent gating of the channel. If [Ca2+] or [Mg2+] at ≥1 mM potentiates activation by acting at a site distinct from the Ca2+ binding site that regulates activation at lower [Ca2+], effects of higher [Ca2+] or [Mg2+] concentrations on channel gating kinetics might be distinct from those of more modest [Ca2+]. The activation and deactivation behavior of Slo1 currents at [Ca2+] up to ∼1 mM has previously been examined in some detail (Cox et al. 1997a; Cui et al. 1997). Here, we have examined the effects of [Ca2+] at up to 10 mM, and also examine current activation and deactivation in the presence of Mg2+.

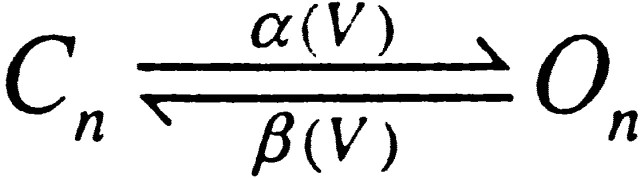

The rate of Slo1 current activation was examined in inside-out patches as a function of both [Ca2+] and voltage with sampling rates and command steps of sufficient duration to allow determination of activation time course. Over a wide range of [Ca2+] and voltage, the activation time course was approximately exponential in nature (Fig. 6), although some initial delay in activation was observed. Representative currents activated at either +40 or +80 mV with [Ca2+] of 1–100 μM are shown in Fig. 6 (A and B). In Fig. 6C and Fig. D, the currents were normalized to their maximal steady-state amplitude and each fit to a single exponential. To facilitate comparison of changes in activation rate, the normalized current activation time course for currents activated over approximately two orders of magnitude of [Ca2+] is plotted on a logarithmic time base in Fig. 6E and Fig. F. At both +40 and +80 mV, 10-fold changes in concentration produce an approximately three to fivefold change in activation rate over this range of [Ca2+]. In Fig. 7A and Fig. B, currents activated by 300 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM Ca2+ are plotted for both +40 and +80 mV. The normalized currents are plotted on both a linear scale (Fig. 7C and Fig. D) and logarithmic time base (Fig. 7E and Fig. F) showing that the increase in [Ca2+] from 300 μM to 10 mM results in only a small additional increase in activation rate, compared with the large changes seen in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

The current activation rate increases substantially as Ca2+ is raised from 1 μM to 100 μM. In A, currents were activated by a voltage step to +40 mV with Ca2+ concentrations of 0, 1, 4, 10, 30, 60, and 100 μM as indicated. In B, currents were activated in the same patch by a voltage-step to +80 mV with the same Ca2+ concentrations. In C, currents activated by the step to +40 mV were normalized to their maximal amplitude and fit with single exponentials. The activation time constants (τa) were 5.45, 3.38, 1.21, 1.05, and 0.80 ms, for 4, 10, 30, 60, and 100 μM, respectively. In D, the normalized current activation time course for the voltage-steps to +80 mV are shown. τa's were 7.08, 3.77, 1.23, 0.53, 0.46, and 0.39, for 1, 4, 10, 30, 60, and 100 μM Ca2+, respectively. In E and F, the same normalized traces shown in C and D are plotted on a logarithmic time base to show the shift in activation time course with Ca2+. An increase in Ca2+ from 1 to 10 μM produces a similar three to fourfold change in activation rate as the increase from 10 to 100 μM. At +40 mV, the trace in response to 4 μM Ca2+ is plotted since at 1 μM there is almost no detectable current activation.

Figure 7.

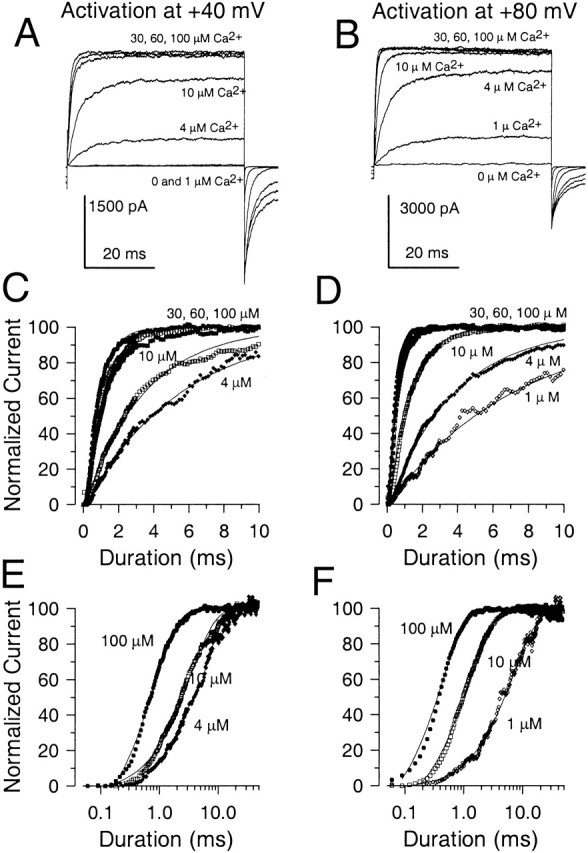

Increases of Ca2+ from 300 μM to 10 mM produce smaller increases in current activation time rate. In A and B, currents were activated by 300 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM Ca2+ at either +40 mV (panel A) or +80 mV (panel B). In C and D, each trace in A and B was normalized to the maximal current amplitude to compare the activation time course. Points show every fourth digitized current value. Solid lines are the best fit of a single exponential function to the activation time course. At +40 mV, the activation time constant (τa) was 0.73, 0.52, and 0.33 ms for 300 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM Ca2+, respectively. At +80 mV, τa was 0.38, 0.28, and 0.19 ms for 300 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM Ca2+, respectively. In E and F, the normalized current activation time course is plotted on a logarithmic time base to allow better comparison of the relatively small concentration dependence of the activation rate for this 30-fold change in concentration compared with that shown in Fig. 6.

The effect of mM Mg2+ on τa was examined as above. The effects of 1 and 10 mM Mg2+ on currents activated with 300 μM Ca2+ are displayed in Fig. 8 (A and B). At 10 mM Mg2+, there is a substantial shift in the G-V curve and substantial open channel block, but the activation course is similar to that in the absence of Mg2+. Comparison of the activation time course of the normalized currents either on a linear (Fig. 8C and Fig. D) or logarithmic (Fig. 8E and Fig. F) time base further emphasizes the lack of effect of Mg2+ on τa in the presence of 300 μM Ca2+. Thus, at potentials where additional depolarization would enhance current activation rate, concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ above 1 mM have little effect on current activation rates. Thus, the lack of effect of Mg2+ on τa indicates that, whatever the mechanism of action of Mg2+ (and mM Ca2+), it does not affect the voltage-dependent rate limiting activation steps.

Figure 8.

Addition of Mg2+ concentrations which markedly shift G-V curves does not increase the limiting rate of Slo1 current activation. In A and B, traces were elicited in each panel with 300 μM Ca2+ alone, and with 300 μM Ca2+ with either 1 mM or 10 mM Mg2+. Traces on the left were activated by a voltage step to +40 mV and, on the right, to +80 mV. In C and D, the normalized current activation time course is plotted on a linear time base (every fourth digitized value is plotted), while, in E and F, the same traces are shown on a logarithmic time base. Solid lines are fits of a single exponential function to the activation time course. At +40 mV, τa was 0.75, 0.64, and 0.59 ms for 300 μM Ca2+, 300 μM Ca2+ + 1 mM Mg2+, and 300 μM Ca2+ + 10 mM Mg2+, respectively. At +80 mV, τa was 0.38, 0.36, and 0.33 ms for each solution. Raising Mg2+ up to 10 mM results in little effect on the time course of current activated in the presence of 300 μM Ca2+.

The dependence of τa on voltage is plotted for 0–300 μM Ca2+ in Fig. 9 A and for 300 μM–100 mM Ca2+ in Fig. 9 B. Again at Ca2+ above 300 μM, the change in τa is much smaller than at lower [Ca2+]. Furthermore, at each [Ca2+], the dependence of τa on voltage is similar. There appears to be an anomalous aspect of the effect of Ca2+ on activation in comparing the results at 0 and 1 μM Ca2+. Specifically, there is a slowing of activation at potentials of +100 mV and more positive as [Ca2+] is elevated to 1 μM, whereas activation is again faster at 4 μM. We have not examined other concentrations over the range of 0 to 4 μM. This result is consistently observed in different sets of patches both in our own experiments and those of others (Cui, J., personal communication). For comparison to the effects of Ca2+, the effect of 1 to 100 mM Mg2+ on current activation elicited with 300 μM Ca2+ is shown in Fig. 9 C. Over the range of −60 through +190 mV, Mg2+ is essentially without effect on current activation rates, with only some slowing of activation at 50 and 100 mM Mg2+.

Time constants were converted to activation rates and the mean rate of activation is plotted as a function of [Ca2+]i from 1 μM to 50 mM in Fig. 9 D for potentials of +20, +60, +100, and +140 mV. The rate of activation at a given voltage increases markedly with increases in [Ca2+] up to ∼1 mM before exhibiting saturation over millimolar concentrations that still produce additional shifts in GV curves. The dependence of activation rate on [Ca2+] (ignoring the rate at 0 Ca2+) was fit with the following function:

|

2 |

where k(Ca) is the rate of activation at a given [Ca2+], kmin is the minimal activation rate, kmax is the limiting rate at saturating [Ca2+], K D is the concentration of half-maximal Ca2+ effect, and n is a Hill coefficient. The limiting activation rate increases with depolarization at and above 1 μM [Ca2+], while the apparent K d is also shifted to lower concentrations with depolarization. The Hill coefficient shows little variation with voltage.

The saturation in Slo1 current activation rate is consistent with the idea that a key Ca2+-dependent step no longer influences current activation rates at [Ca2+] above 1 mM. However, despite the fact that additional elevations in [Ca2+] do not increase the activation rate, additional depolarization can result in faster current activation. Thus, the saturation in the Ca2+ dependence of activation rate is unrelated to any limit on the channel activation process itself. Rather, the limiting activation rate at saturating [Ca2+]i does vary with voltage, consistent with the idea that solely voltage-dependent transitions determine the limiting rate of activation at [Ca2+] of 1 mM and above.

The effect of Mg2+ on current activation is summarized in Fig. 9 E. When currents were activated with 300 μM Ca2+, additions of [Mg2+] from 1 through 100 mM resulted in no additional increase in current activation rate. In fact, at [Mg2+] above 10 mM, a slowing in the activation rate was observed, consistent with the idea that Mg2+ may inhibit Ca2+ binding at the low affinity activation site (Shi and Cui 2001b). We also examined the effect of Mg2+ on activation of current with 0 Ca2+/5 mM EGTA. It was shown earlier that Mg2+ slows current activation with 10 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 5), an effect probably resulting from an inhibitory effect of Mg2+ on the high affinity Ca2+ binding site. However, with 0 Ca2+, there was essentially no effect of 10 mM Mg2+ on activation time constant at potentials positive to +160 mV, whereas at more negative potentials and less than maximal open probabilities, activation and deactivation were slowed, both effects probably resulting from the effects of Mg2+ on transitions involved in deactivation described below. Thus, Mg2+ does not appear to directly influence rate limiting, voltage-dependent activation steps in the absence of Ca2+. However, it should be noted that, with 0 Ca2+ and [Mg2+] above 10 mM, we also observed an increase in current activation rate (Fig. 9 E) that cannot be easily accounted for by the mechanisms presented below.

Deactivation Is Slowed by Either Increases in Ca2+ or Mg2+

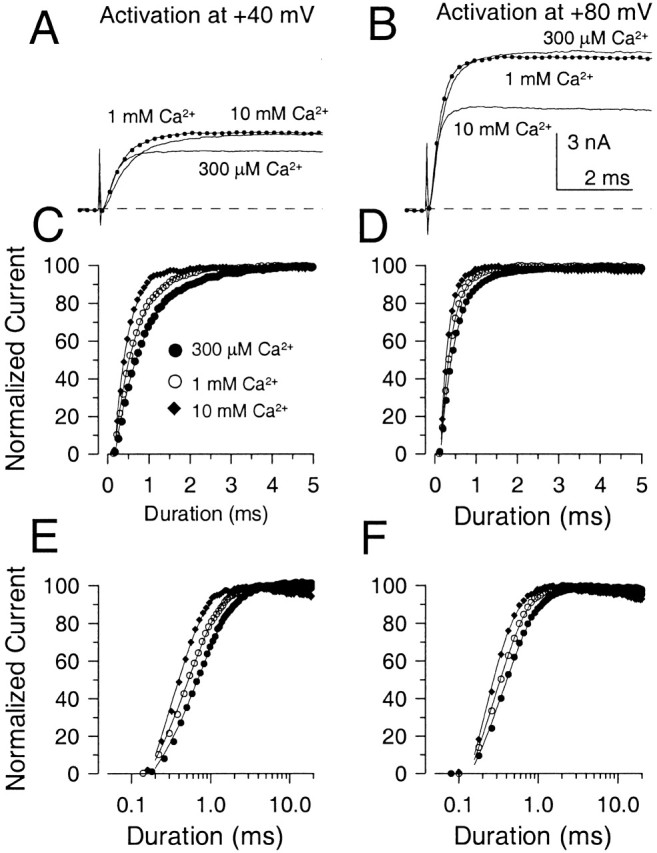

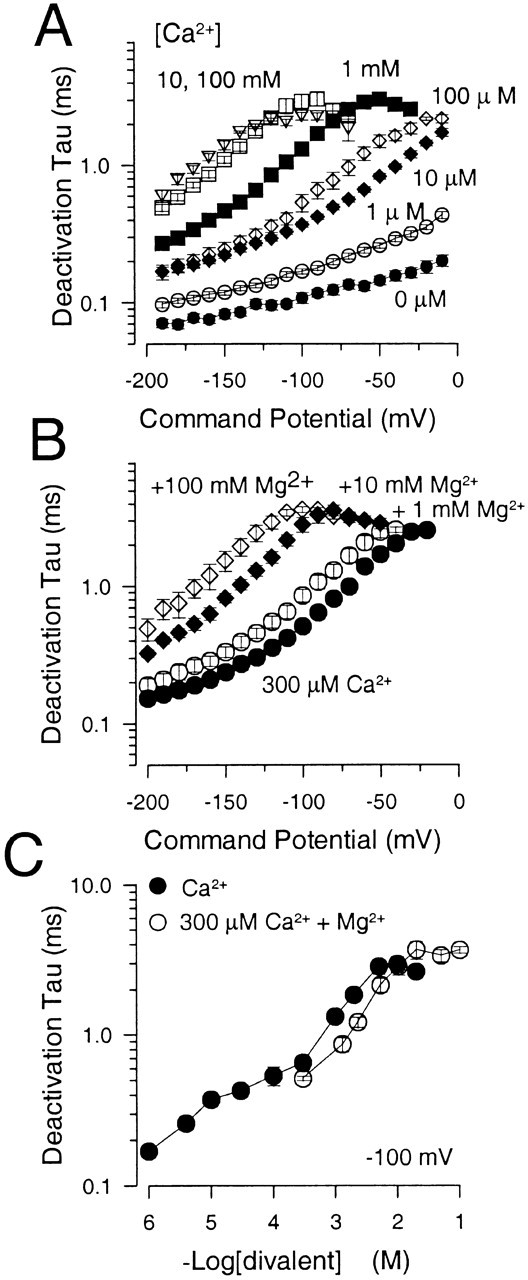

Deactivation tails resulting from closure of Slo1 channels after repolarization were examined over a range of potentials with [Ca2+] from 0 μM to 100 mM. Deactivation, under most conditions, could be described by a single exponential. The deactivation time constant (τd) is plotted as a function of voltage in Fig. 10 A over Ca2+ concentrations spanning six orders of magnitude. Similarly, τd is plotted as a function of voltage in Fig. 10 B for solutions containing 300 μM Ca2+ with or without either 1, 10, or 100 mM Mg2+. The dependence of τd on Ca2+ and Mg2+ appears similar but differs from the dependence of τa on Ca2+ and Mg2+. Namely, increases in [Ca2+] above 100 μM continue to result in additional slowing of current deactivation, implying that there may be Ca2+-dependent effects at higher [Ca2+] that influence rates of exit from open states or closed states near open states, but which have no affect on the limiting rates of channel activation. Similarly, although Mg2+ is without effect in substituting for Ca2+-dependent activation steps, Mg2+ does slow deactivation in a fashion qualitatively similar to the effect of mM Ca2+. For both Mg2+ and Ca2+, the slowing of deactivation is substantial over the range of 1–10 mM of either cation, concentrations at which activation rates are unaffected. However, above 10 mM of either cation, there is an indication that the effect on deactivation exhibits saturation, which is consistent with the saturation in the shift of G-V curves at high divalent cation concentrations. The change in τd as a function of [Mg2+] is plotted in Fig. 10 C and compared with the effect of a similar total concentration of divalent with Ca2+ alone. Millimolar concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ appear similar in their effects on deactivation.

Figure 10.

Millimolar concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ have similar effects on current deactivation. In A, the deactivation time constants are plotted as a function of command potential for [Ca2+] spanning over six orders of magnitude, 1 μM–100 mM. Points and error bars are means and SEM of 5–15 patches. In B, the deactivation time constants are plotted as a function of command potential for tail currents obtained with 300 μM Ca2+ and 300 μM Ca2+ plus 1, 10, and 100 mM added Mg2+. Points show means and SEM for 4–8 patches. In C, the deactivation time constant measured at −100 mV is plotted as a function of total [divalent] for solutions with only Ca2+ (•) and for solutions with 300 μM Ca2+ with added Mg2+ (○). The slowing of deactivation with either elevated Ca2+ or Mg2+ exhibits saturation, although at somewhat different concentrations.

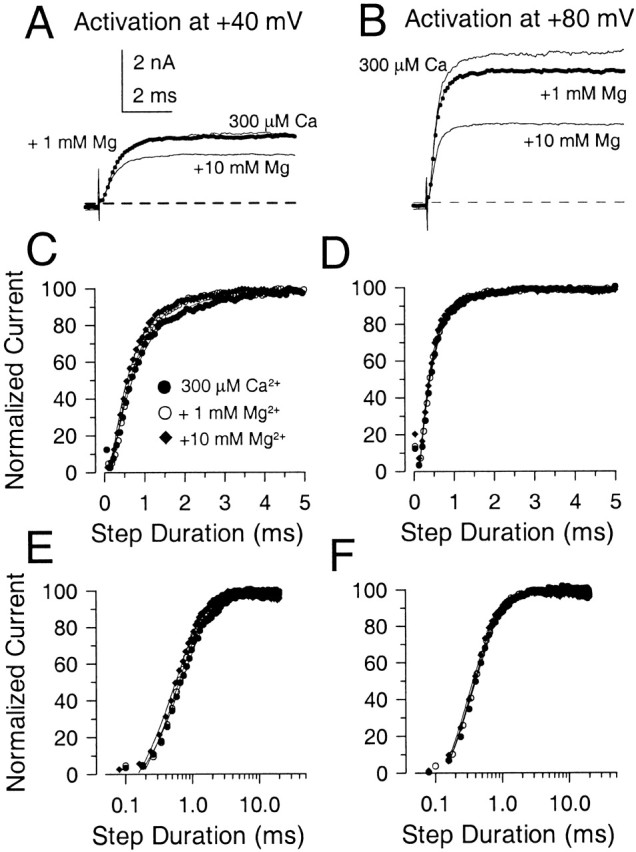

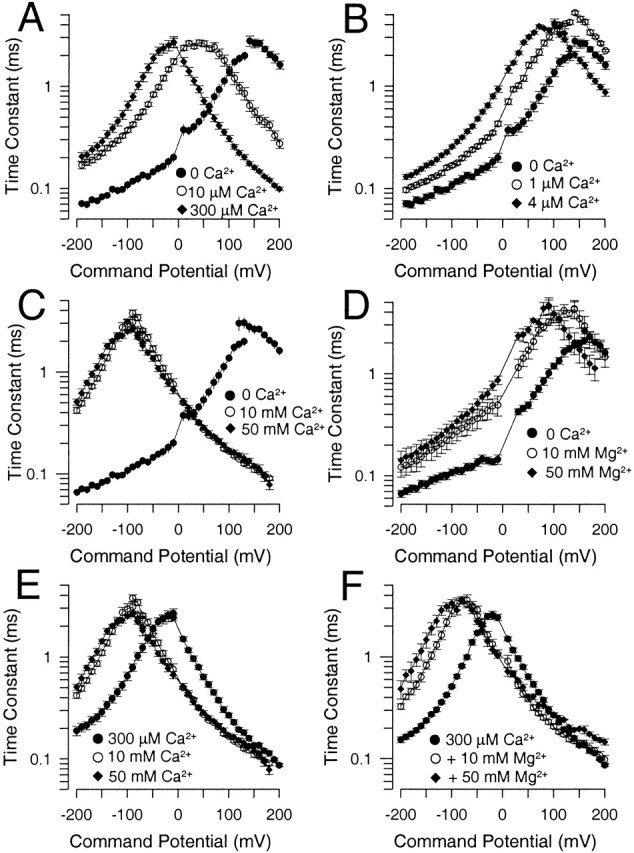

To summarize the similarities and differences in the effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ on kinetic aspects of Slo1 currents, effects of various [Ca2+] and [Mg2+] were compared in the same sets of patches. At any given [Ca2+] and [Mg2+], the relaxation time constant (deactivation and activation) exhibits an approximately bell-shaped dependence on voltage. In Fig. 11 A, 10 μM Ca2+ is shown to shift both activation and deactivation times constants to a somewhat similar extent compared with 0 Ca2+, whereas with 300 μM Ca2+, the effects on τd begin to diminish while effects on activation remain pronounced. In Fig. 11 B, 4 μM Ca2+ produces a leftward shift qualitatively similar to that with 10 μM, although smaller. 1 μM Ca2+ results in the unusual slowing of activation described above, producing a slowing of the principle time constant at all voltages. In Fig. 11C and Fig. D, Fig. 10 and 50 mM Ca2+ are compared with 10 and 50 mM Mg2+. 10 and 50 mM Ca2+ produce a similar leftward shift in the relaxation time constant. In contrast, with 10 mM Mg2+, there is no apparent effect on current activation, but deactivation is slowed. 50 mM Mg2+ produces some slight additional slowing in deactivation, but also results in some increase in current activation rate. In Fig. 11 E, 10 and 50 mM Ca2+ are shown to produce a substantial additional slowing of deactivation relative to 300 μM Ca2+, with only weaker effects on current activation at positive potentials. The effects of 10 and 50 mM Mg2+ when added to 300 μM Ca2+ are quite similar (Fig. 11 F), producing a substantial slowing of current deactivation, with little effect on current activation, except for a clear slowing of activation at 50 mM. Thus, these kinetic effects remain generally consistent with the effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ on GV curves. There is a higher affinity effect of Ca2+ that influences both current activation rates and deactivation rates. There is little evidence that Mg2+ acts at this site except for a slowing of activation, when [Mg2+] is perhaps at least three orders of magnitude greater than [Ca2+]. In contrast, both Mg2+ and Ca2+ share an ability to slow deactivation at mM concentrations, while having minimal effects on limiting rates of current activation at these concentrations.

Figure 11.

Comparison of effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ on primary time constant of Slo1 current relaxations. In A, activation and deactivation time constants obtained at 0, 10, and 300 μM Ca2+ are plotted as a function of potential. In B, the shift in relaxation time constant with 1 and 4 μM are compared with 0 μM Ca2+. Note the unusual slowing of activation with 1 μM Ca2+. In C, the effects of 10 and 50 mM Ca2+ are compared with 0 Ca2+, whereas, in D, the effects of 10 and 50 mM Mg2+ are compared with 0 Ca2+. In E, the effects of 10 and 50 mM Ca2+ are compared with 300 μM Ca2+, whereas, in F, the effects of 10 and 50 mM Mg2+ plus 300 μM Ca2+ are compared with 300 μM Ca2+.

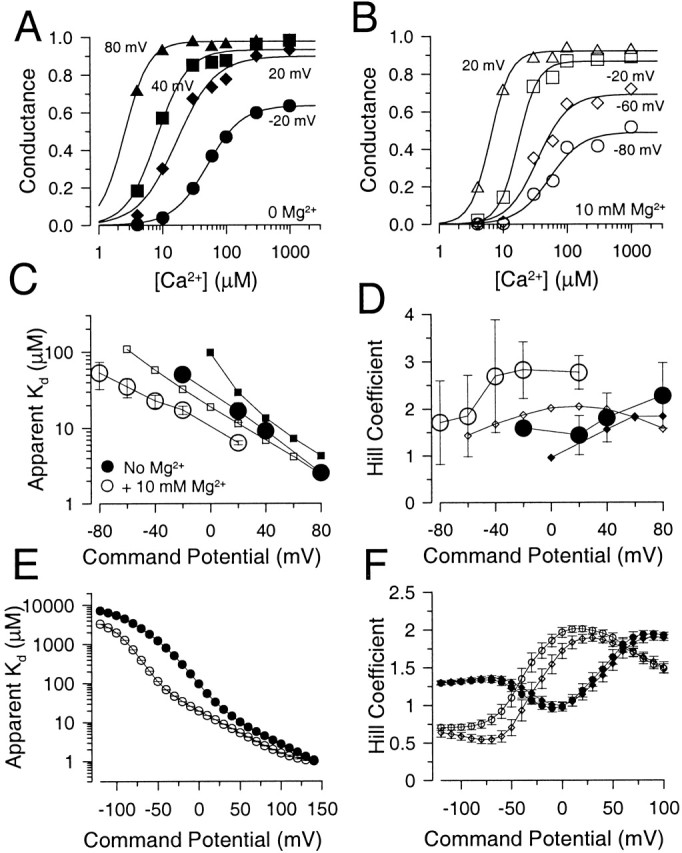

Mg2+ Increases the Hill Coefficient for Activation of Slo1 Current by Ca2+ by Shifting the Relationship between Hill Coefficient and Membrane Potential

One interesting aspect of the effect of Mg2+ reported in earlier studies was that Mg2+ increases the Hill coefficient for activation by Ca2+ of BK channels in bilayers (Golowasch et al. 1986) and that other divalent cations act similarly (Oberhauser et al. 1988). For gating by Ca2+, the Hill coefficient is generally used as an indicator of the minimal number of Ca2+ ions that are required for channel activation. Where this has been examined for Slo1 current, the Hill coefficient is typically around two with some tendency to increase with depolarization (Cui et al. 1997; Bian et al. 2001). Here, we addressed this issue in two ways. First, we examined the behavior of the Hill coefficient over a wider range of [Ca2+] than previously studied to assess how the proposed two binding sites might impact on Hill plots. Second, we determined whether effects of Mg2+ on the Hill coefficient would be reproduced here. To address the first issue, normalized conductance values from Fig. 2 C were replotted to display the relationship between conductance and [Ca2+] over a range of voltages (Fig. 12 A). Curves obtained at each command potential were fit with a Hill equation G/Gmax = B + A/[1 + (K d/[Ca])n, where n is the Hill coefficient and K d is the apparent Ca2+ dissociation constant. B is a term included to account for the Ca2+-independent activation of current at the most positive activation potentials. At some voltages, this function did not describe the shape of the relationship between conductance and [Ca2+| very well. However, terms for the K d (Fig. 12 C) and Hill coefficient (Fig. 12 D) were determined for voltages from −120 to +140 mV. The apparent affinity increases markedly with depolarization while appearing to reach a limiting value at the most negative activation potentials. The apparent Hill coefficient exhibits a surprisingly erratic appearance. However, consistent with other results (Cui et al. 1997), the Hill coefficient increases from ∼1 to ∼2.5 over the range of −20 to +80 mV. The error bars indicate the 90% confidence limits on the fitted parameter and indicate that the fitting function in some cases did not describe the shape of the curves very adequately. This sort of experiment suggests that two other factors are also likely to impact on estimates of Hill coefficient in various studies. First, large variation in estimates of Hill coefficient might be expected to result from the fact that, in some studies, the number of Ca2+ concentrations over which the change in conductance is determined can be rather minimal. Second, at positive potentials where activation of current occurs in the absence of Ca2+, if this activation is not taken into account, Hill coefficients will be estimated incorrectly. In sum, these results suggest that a typical Hill function may not be a mechanistically meaningful way of evaluating the Ca2+ dependence of Slo1 current activation and that the apparent Hill coefficient may exhibit some unusual dependence on voltage. Possible reasons for this behavior are addressed below.

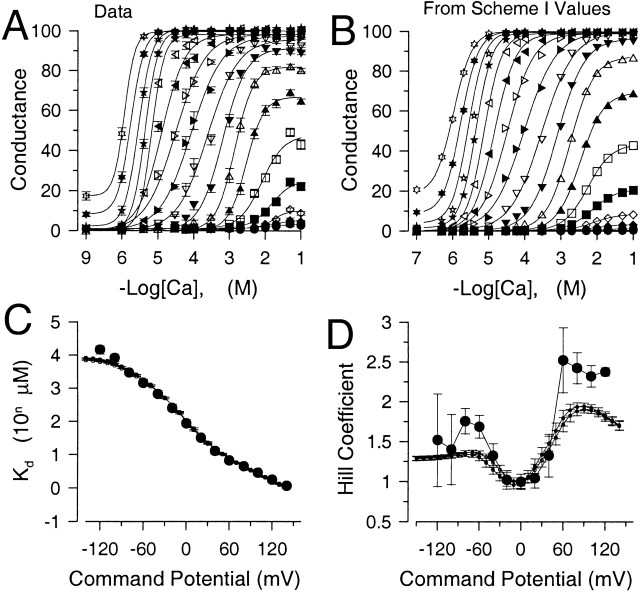

Figure 12.

The behavior of K d and Hill coefficient over all [Ca2+]. In A, conductances given in Fig. 2 D were replotted to show the Ca2+ dependence of conductance at a given voltage. Each point is the mean and SEM for the estimate. Solid lines are fits of the modified Hill equation given in the text. Symbols correspond to potentials of −200 (•), −180 (○), −160 (♦), −140 (⋄), −120 (▪), −100 (□), −80 (▴), −60 (▵), −40 (▾), −20 (▿), 0 (▸), +20 (▹), +40 (◂), +60 (◃), +80 (★), +100 (⋆), +120 (closed six-pointed star), and +140 (open six-pointed star) mV. In B, conductance values predicted from Fig. 1 (see Fig. 14) based on values given in Table (column D) were plotted as a function of [Ca2+] and fit with the modified Hill equation (solid lines). Symbols are as in A. In C, estimated values for the K d for apparent Ca2+ affinity (•) obtained from fitting the data in Fig. 12 A are plotted as a function of command potential. The solid line with small filled circles corresponds to values for K d predicted from Fig. 1 as shown in Fig. 12B. The line with small open circles corresponds to K d values assuming no Mg2+ inhibition of the high affinity site. In D, the Hill coefficients determined from Fig. 12 A (•) are plotted as a function of voltage. Error bars represent the 90% confidence limit on the estimate of the Hill coefficient. The dotted lines show the predictions from Fig. 1 as determined from values in Table , column D (Fig. 12 B, small closed circles) or from Table , column F (small open circles, no Mg2+ inhibition).

We next examined the effects of [Mg2+] on the behavior of Hill plots. This analysis used a different set of patches than those used in Fig. 2 and used a more limited set of Ca2+ concentrations, but typical of those used in other investigations. Hill plots obtained for this data set in the absence of Mg2+ are shown for several voltages in Fig. 13 A, whereas similar plots in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ are shown in Fig. 13 B. As above, the Hill equation was used to make estimates of K d and the Hill coefficient. Given the more limited number of Ca2+ concentrations used in this set of patches, the estimate of Hill coefficient in particular exhibited large confidence limits. Both with and without Mg2+, the K d varied exponentially with command potential with a zero-voltage K d of ∼25 μM in the absence of Mg2+ and ∼10 μM in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 13 C). Both with and without Mg2+, there was a trend for the Hill coefficient to became larger at more positive potentials (Fig. 13 D), which is consistent with the observations in Fig. 12 D and other work (Cui et al. 1997). This increase in the Hill coefficient is, in part, the simple expectation of the fact that, for each increment in Ca2+, G-V curves are shifted more at lower than at higher [Ca2+], such that over the range of 100 μM–1 mM Ca2+, little additional shift is observed (Wei et al. 1994; Cox et al. 1997b). As a consequence, at more negative potentials, relatively large increments in [Ca2+] produce relatively small increases in conductance, resulting in a less steep Ca2+ dependence of activation. Since, as shown above, 10 mM Mg2+ produces an essentially 50-mV leftward shift of the G-V curve obtained at each [Ca2+], this would be expected to cause an apparent increase in Hill coefficient at any command potential. Another way of viewing the results is that the relationship between Hill coefficient and command potential (Fig. 13 D) is simply shifted leftward ∼50 mV in the presence of Mg2+. Thus, the present results suggest that Mg2+ does cause an increase in the apparent Hill coefficient for Ca2+ at a given voltage, but that this effect reflects a shift of the relationship between Hill coefficient and voltage along the voltage axis.

Figure 13.

The apparent Hill coefficient for activation of conductance by Ca2+ is increased by Mg2+. In A, each point is the estimate of conductance activated at a given Ca2+ and voltage obtained from normalized G-V curves. Solid lines are fits of the modified Hill equation given in the text. Fitted values for apparent K d and Hill coefficient are plotted in C and D, respectively. Values used in this figure were from a different set of patches than shown in Fig. 2 or Fig. 12. In B, conductance estimates obtained in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ are plotted as a function of Ca2+ for a range of voltages. At comparable voltages, the Hill coefficient for activation is higher in the presence of Mg2+. In C, the apparent K d (in μM) for activation of conductance by Ca2+ either in the absence (•) or presence (○) of 10 mM Mg2+ is plotted as a function of activation potential. The apparent Ca2+ affinity is increased at a given potential in the presence of Mg2+. The error bars are 90% confidence limits from the estimates of K0.5 obtained in A and B. Predictions from Fig. 1 (Table , column D) for solutions without Mg2+ (▪) or with Mg2+ (□) are also shown. In D, the Hill coefficient and confidence limits for the activation of conductance by Ca2+ either in the absence (•) or presence (○) of Mg2+ are plotted as a function of command potential, along with estimates (no Mg2+ [♦], +10 mM Mg2+ [⋄]) from Fig. 1 based on estimates of Mg2+ affinities from column B of Table . Both for experimental data and the theoretical predictions, there is a trend for increased Hill coefficient at more positive potentials and, at any given potential, Mg2+ increases the apparent Hill coefficient. In E, the K d for Ca2+ effect predicted from Fig. 1 is plotted over a wider range of potentials. Both with (○) and without (•) 10 mM Mg2+, at the most negative potentials a limit in the K d is observed, while affinity increases dramatically with depolarization. In F, the behavior of Hill coefficient as a function of command potential predicted by Fig. 1 is displayed over a wider range of potentials. Predictions from Fig. 1 assuming Mg2+ inhibition of the high affinity site (Table , column D) are shown both without (•) and with (○) 10 mM Mg2+. Predictions from Fig. 1 with no Mg2+ inhibition (Table , column F) are also shown without (♦) and with (⋄) 10 mM Mg2+.

Mg2+ Produces Shifts of G-V Curves Resulting from α + β1 Subunit Coexpression

The ability of Mg2+ to shift G-V curves at a given Ca2+ is somewhat reminiscent of the effect of the β1 and β2 auxiliary subunits of BK channels (McManus et al. 1995; Meera et al. 1996; Wallner et al. 1999; Xia et al. 1999). If Mg2+ were acting to mimic the effects of an associated β subunit, Mg2+ might be ineffective on channels resulting from α + β subunit coexpression. To test this possibility, the effects of different concentrations of Mg2+ on α + β1 currents elicited with 100 μM Ca2+ were examined. Normalized G-V curves were generated for a set of four patches. The V0.5 for current activation with 100 μM Ca2+ was −110.9 ± 1.5 mV, whereas, for 1, 2, 10, and 20 mM Mg2+, values for V0.5 were −123 ± 2.4 mV, −129.7 ± 1.6 mV, −140.0 ± 1.3, and −148.9 ± 1.3 mV, respectively. In this set of patches, the net effect of 10 mM Mg2+ is to shift the V0.5 about −30 mV, which is less than observed in the absence of the β1 subunit. However, it is clear that Mg2+ is able to exert much of its effect, irrespective of the presence or absence of the β1 subunit.

Effects of Mg2+ Do Not Result from Changes in Ca2+ Binding Affinity

The primary effects of Mg2+ that require explanation are as follows. First, 10 mM Mg2+ appears to produce a similar shift in V0.5 at both 0 and 300 μM Ca2+ with somewhat smaller shifts at 4 and 10 μM. Second, Mg2+ does not substitute for Ca2+ in the high affinity Ca2+-dependent steps that participate in increases in current activation rate. Third, mM Mg2+ shares with mM Ca2+ the ability to slow deactivation, an effect which does not exhibit saturation until over 10 mM divalent. Finally, Mg2+ produces a slowing of current activation with 4 and 10 μM Ca2+ under conditions of near maximal current activation. Can these effects be accounted for by a single mechanism of action?

To guide our thinking, we first consider the particular 50-state model presented by Cox and Aldrich 2000 to account for the dependence of steady-state conductance on voltage and Ca2+. The steady-state predictions of their formulation are summarized in the following equation:

|

3 |

where B = [(1 + Ca/Kc)/(1 + Ca/Ko)]4 with Kc is the Ca2+ binding equilibrium for the closed channel, Ko is the Ca2+ binding equilibrium for the open channel, L(0) is the open-to-closed equilibrium constant when no voltage sensors are active and no Ca2+ binding sites are occupied, Q, the gating charge associated with this closed to open equilibrium, Vhc, is the voltage at which a single voltage sensor is active half the time when the channel is closed, and Vho, is the voltage at which a single voltage sensor is active half the time when the channel is open, and Z is the equivalent gating charge associated with each voltage-sensor's movement. This formulation assumes that voltage-dependent transitions and Ca2+ binding transitions in each subunit are independent and that Ca2+ binding affinity is not influenced by movement of voltage sensors.