Abstract

As revealed over the past twenty years, the insulin signaling cascade plays a central role in regulating immune and oxidative stress responses that affect the life spans of mammals and two model invertebrates, the nematode Caenorhabitis elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. In mosquitoes, insulin signaling regulates key steps in egg maturation and immunity and likely affects aging, although the latter has yet to be examined in detail. Reproduction, immunity and aging critically influence the capacity of mosquitoes to effectively transmit malaria parasites. Current work has demonstrated that molecules from the invading parasite and the blood meal elicit functional responses in female mosquitoes that are regulated through the insulin signaling pathway or by cross-talk with interacting pathways. Defining the details of these regulatory interactions presents significant challenges for future research, but will increase our understanding of mosquito/malaria parasite transmission and of the conservation of insulin signaling as a key regulatory nexus in animal biology.

Keywords: insulin, Anopheles, Plasmodium, mosquito, malaria, aging, oxidative stress, innate immunity, nitric oxide, transforming growth factor, β

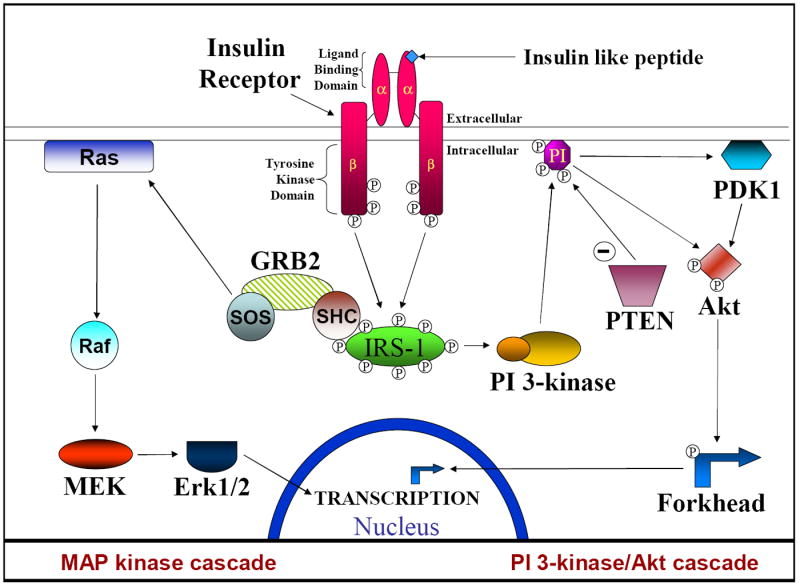

In all well-studied metazoans, metabolism, growth, and longevity are coordinately regulated via a nexus that involves signaling cascades activated by insulin and insulin-like growth factors (IGF). Although these pathways differ in downstream physiological effects and some of their signaling proteins, the proteins themselves and their scaffolding interactions are largely conserved among model organisms (Fig. 1), particularly in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and the mouse Mus musculus. This review will examine our current understanding of how the insulin and IGF signaling cascades (ISC) regulate immunity in these diverse model organisms. In addition, we will explore how recent research on three biomedically important mosquitoes links the ISC to regulation of metabolism, aging, and immunity to pathogens responsible for diseases such as malaria.

Figure 1. The insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling cascade (ISC).

The ISC is initiated by an insulin-like peptide binding to the α subunit of the insulin receptor. This induces the autophosphorylation of the β subunit which in turn phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1). Phosphorylated tyrosine residues provide a binding site for the regulatory subunit of PI 3-kinase and SHC representing the major branching point between the PI 3-kinase (PI-3K)/Akt and Ras/Raf/MEK/Erk cascades. PI 3-kinase/Akt cascade: Upon PI 3-kinase binding to IRS-1 the catalytic subunit is released and travels to the cell membrane where it converts PI(4,5)P2 into PI(3,4,5)P3. PI(3,4,5)P3 provides binding sites for both Akt and PDK1 and brings these proteins together. Phosphorylation of Akt by PDK1 activates the kinase activity of Akt, allowing it to phosphorylate extranuclear Forkhead transcription factors. These transcription factors can then translocate across the nuclear membrane and begin transcription of a variety of proteins. PTEN dephosphorylates PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2 and thus acts to down-regulate the PI 3-kinase cascade. MAP kinase cascade: Upon activation the GRB2/SOS complex binds and activates Ras, which in turn recruits Raf to the cell membrane and activates it. The activated Raf subsequently activates MEK, which in turn activates Erk. Erk can then enter the nucleus to phosphorylate and activate transcription factors such as Elk-1.

1. Insulin signaling, innate immunity and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans

In C. elegans, insulin signaling presumably is initiated by the binding of insulin-like peptides (ILPs), of which there are at least 38 [1], to a receptor tyrosine kinase, daf-2, that is an apparent homolog to the vertebrate insulin/IGF receptor. Based largely on interpretations from studies with various genetic mutants, daf-2 activates AGE-1, a phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI-3K), which in turn activates Akt/protein kinase B. Importantly, activated Akt can directly phosphorylate daf-16, a Forkhead transcription factor ortholog, which inactivates daf-16 by excluding it from the nucleus [2]. In the absence of insulin signaling, unphosphorylated daf-16 can enter the nucleus and control transcription, indicating that the actions of daf-2 and daf-16 oppose each other. This fact is highlighted by mutants with opposed physiologies: daf-2 loss-of-function mutants are long-lived and resistant to oxidative stress and bacterial infection, whereas daf-16 loss-of-function mutants are short-lived and susceptible to oxidative stress and infection [3, 4].

Key targets of daf-16 regulation include genes for mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and glutathione S-transferase, which are closely linked to aging in C. elegans and other organisms, and genes for numerous C-type lectins, which play critical roles in cell adhesion and pathogen recognition [5]. Downregulation of these gene targets in daf-16 mutants would be predicted to enhance oxidative stress, which has been linked directly to aging in C. elegans [6, 7], and decrease pathogen recognition [8]. Conversely, rescue of downregulated MnSOD has been shown to reverse accelerated aging and mortality due to oxidative stress [6]. Specifically, Melov et al. [6] reported that dietary supplementation of C. elegans with the SOD mimic EUK-8, which accumulates in mitochondria in mammalian cells [9], significantly increased the lifespan of normal C. elegans. Keaney et al. [9], however, reported that EUK-8 extends lifespan in oxidatively stressed, but not in unstressed nematodes. Despite these differences, studies of selected gene mutations in C. elegans generally support the “oxidative stress hypothesis of aging,” that is, both normal and accelerated aging and mortality are the result of accumulated oxidative damage. As such, when daf-16 expression is activated, oxidative stress is reduced, and lifespan is extended. Conversely, when daf-16 expression is inhibited, oxidative stress is enhanced, and lifespan is shortened.

In C. elegans, the intestine and germ tissue play pivotal roles in signaling crosstalk that are critical for normal development and aging. Indeed, the intestine has been defined as a “signaling center” from which overexpressed daf-16 can completely restore the longevity of daf-16 germline-deficient nematodes and significantly increase the lifespan of these mutants [10]. Libina et al. [10] proposed that overexpressed daf-16 acts to control lifespan by downregulating a daf-2 agonist or by upregulating a daf-2 antagonist. Interestingly, the observations of Murphy et al. [11] support this hypothesis: expression of the insulin-like peptide gene ins-7, which encodes a putative daf-2 agonist, was elevated in nematodes in which daf-16 expression was knocked down and reduced in nematodes engineered to overexpress daf-16. It is possible that reduced ins-7 expression results in reduced secretion of bioactive peptide, and as such, is perceived by surrounding cells and tissues as reduced insulin signaling, which results in the spread of daf-16 activation. Such signal spread via the ISC is predicted to underlie the mechanisms of aging and would also be expected to enhance survivorship following immune challenge through coordination of local and systemic anti-pathogen responses.

2. Insulin signaling and physiology in Drosophila melanogaster

The conservation of an ISC pathway in D. melanogaster and its regulation of diverse processes have been explored largely through the phenotypic effects of genetic mutations, and they are similar to those for C. elegans. For example, D. melanogaster homozygous for a P-element insertion of chico, the insulin receptor substrate gene, exhibited a 48% increase in lifespan relative to wild type flies [12]. Mutant flies also exhibited enhanced levels of SOD activity [12]. Similarly, flies with mutant alleles of the insulin receptor [13] and engineered to overexpress the Forkhead transcription factor, dFOXO, in the pericerebral fat body [14] exhibited enhanced longevity relative to wild type flies. Overexpression of dFOXO in pericerebral fat body also induced nuclear localization of dFOXO in peripheral fat body, which would be expected to repress insulin-dependent signaling in this tissue [14]. The latter observations would suggest that signal spread in fruit flies may mimic that observed in C. elegans.

In other studies, targeted ablation of neurosecretory cells that secrete ILPs in adult flies resulted in a 30-40% reduction in expression of the ILP genes dilp2, dilp3, and dilp5, increased lifespan by up to 33% in mated female flies, increased resistance to oxidative stress, and resulted in significantly higher levels of trehalose (64% increase), glycogen (44% increase), and lipids (10% increase) when compared with controls [15]. Bayne et al. [16] reported that flies genetically engineered to overexpress MnSOD and catalase in the mitochondria exhibited enhanced resistance to dietary hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and exposure to hyperoxic conditions. However, the authors also noted that lifespan of the flies was decreased rather than increased, and this was associated with decreased physical activity and an age-related decrease in mitochondrial respiration, suggesting that physiological levels of reactive oxygen species are essential for normal biological processes and normal lifespan [16]. Together, these observations indicate that an ISC is involved in the regulation of aging in D. melanogaster through a complex interplay of stress resistance, ILP secretion, and apportionment of metabolic reserves.

In C. elegans, the connection between insulin signaling and innate immunity has been established through immune challenge of ISC mutants [3, 4], but cause-and-effect between insulin signaling and innate immunity in D. melanogaster has not yet been established. A connection between aging and immunity, however, seems clear. Specifically, Zerofsky et al. [17] reported that female fruit flies exhibit immune senescence with age. Older female flies expressed higher levels of the antimicrobial peptide gene diptericin relative to younger female flies when exposed to septic bacterial infections [17]. The response in older flies was attributed to persistent diptericin transcription upon septic exposure, a phenomenon not observed in younger flies. In contrast, when older flies were challenged with killed bacteria, diptericin induction levels were lower than induction levels observed in similarly treated younger flies, suggesting that older females had a reduced capacity to induce diptericin [17]. The authors also showed that fecundity was reduced in immune-activated females via the “immune deficiency” or imd pathway, suggesting that maximum reproduction occurs in young flies, perhaps as a benefit from increased regulation of the immune response [17].

3. The ISC, innate immunity and aging in mammals

Only a single insulin/IGF receptor has been identified to date in the C. elegans and D. melanogaster genomes, whereas mammals possess distinct receptor tyrosine kinases for insulin and IGF-I, plus a third receptor type of unknown function. Caloric restriction, which increases life-span in rodents [18] and non-human primates (reviewed in [19]), reduces circulating levels of insulin and IGF-I (reviewed in [20]). In a manner similar to the connections between the ISC and aging in other organisms, there is evidence for a role for IGF-I in the control of longevity in mammals. Specifically, mice heterozygous for an IGF receptor mutation exhibited a 33% increase in longevity and upregulated MnSOD activity [21]. In mice, as in fruit flies, overexpression of catalase targeted to the mitochondria lengthened lifespan and reduced oxidative tissue damage, including H2O2-induced aconitase inactivation and the development of mitochondrial deletions relative to control animals [22].

In general, IGF-I and insulin have broad activities in the mammalian innate immune system (reviewed in [23]), and these effects are dose-dependent. Normal circulating levels of mammalian IGF-I range from 0.8 – 1.0 μg/ml (0.11 – 0.13 μM; [24]) and those of insulin are ~ 0.4 ng/ml (6.7 x 10-5 μM or 0.067 nM; [25]). At concentrations as low as 50 ng/ml, IGF-1 can augment the bactericidal activity of murine macrophages by increasing phagocytosis [26] and can synergize with lipopolysaccharide at concentrations from 0.13 – 1.3 nM to induce tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α synthesis by human monocytes and murine macrophages [27]. In contrast to enhancement of immune responses by low concentrations of IGF-I, supraphysiological concentrations of insulin are required to induce similar effects. For example, a 24 h treatment of human monocytes and murine macrophages with 0.13 – 130 nM insulin did not induce TNF-α synthesis; induction was not observed until 24 h after treatment with 1.3 – 13 µM insulin, which is 1,000- to 10,000-fold higher than effective concentrations of IGF-I [27].

In contrast to the effects of IGF-I and insulin on innate immune cells, concentrations of IGF-I of 0.13 μM or greater and concentrations of insulin of 8.6 μM or greater reduced proliferation and antibody synthesis of adaptive immune cells (lymphocytes) relative to control cells in vitro [28]. The anti-inflammatory effects of insulin have been revisited recently in light of the beneficial effects of intensive insulin therapy (IIT) of critically ill patients [28, 29]. These patients typically suffer from stress hyperglycemia, so the beneficial effects of IIT have not been clearly attributed to the prevention of hyperglycemia, which can induce oxidative stress, or to the purported anti-inflammatory effects of elevated levels of insulin in vivo [29, 30].

Taken together, IGF-I and insulin can exert anti- and pro-inflammatory effects on immune cells, but these effects are mediated by low to physiological levels of IGF-I, while an excess of insulin is required to observe similar effects. At high concentrations, insulin can bind to the IGF-I receptor [31], suggesting that the similar effects of insulin and IGF-1 at different doses are due to binding to the IGF-1 receptor. This differential responsiveness is reflective of an increased biological complexity that may have evolved in mammals to focus the effects of circulating insulin on metabolism, whereas the effects of IGF-I were broadened to include growth regulation as well as regulation of longevity and immunity.

4. The ISC and nitric oxide in mammals: positive feedback and control of inflammation

Nitric oxide (NO), one of the smallest known biological molecules, regulates neuronal signaling,vascular physiology and numerous immune functions in mammals including direct pathogen killing (reviewed in [32]). Given the broad biological roles of NO, it is perhaps not surprising that control of insulin action has been connected functionally to NO synthesis in mammals. The synthesis of NO is catalyzed by a two-step oxidation of L-arginine by NO synthase (NOS) and, in mammals, three NOS isoforms have been identified. Two isoforms are commonly associated with endothelial and neuronal physiologies (eNOS, nNOS), while a third (iNOS) is highly inducible and often associated with immune function. These divisions, however, are somewhat artificial in that eNOS and nNOS are inducible by pathogen-associated molecules [33, 34] and iNOS expression has been associated with signaling processes more typically associated with eNOS or nNOS [35].

Shankar et al. [36] showed that catheter delivery to rats of NG-monomethyl-L-arginine, a general inhibitor of NOS activity, induced hyperglycemia by inhibiting insulin secretion and action. These observations suggested that NO-dependent pathways potentiate insulin secretion and action. Conversely, numerous studies have demonstrated insulin induction of NO synthesis, suggesting a positive feedback loop of NO-insulin-NOS induction. For example, Begum and Ragolia [37] reported that 100 nM insulin upregulated iNOS protein levels by nearly three-fold in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Kim et al. [38] reported similar findings for rat osteoblast-like cells. Specifically, 10 nM insulin induced NO synthesis 1.3-fold and 100 nM insulin induced NO synthesis two-fold relative to controls [38]. Insulin induction of NO synthesis was inhibited by the MEK inhibitor PD98059 and induced by overexpression of Erk, indicating that insulin induced NO synthesis via activation of a MEK/Erk-dependent pathway [38]. In contrast to insulin, 100 nM IGF-1 increased NO synthesis by only 57% relative to controls, indicating that iNOS activity in osteoblast-like cells is significantly more sensitive to regulation by insulin than by IGF-1 [38]. In other studies, treatment of human endothelial cells with a concentration of insulin closer to physiological levels (1nM) induced NO synthesis via insulin receptor activation and activation of a downstream pertussis-sensitive GTP-binding protein and Erk 1/2-dependent signaling [39]. Taken together, these results indicate that insulin induces NO synthesis through multiple pathways and that NO synthesis is critical for insulin secretion and action. An insulin-NO positive feedback loop would be predicted to enhance the pro-inflammatory effects of insulin and to facilitate signal spread given the diffusion of NO across closely opposed cell membranes.

5. Endocrinology of insulin-like peptides and links to innate immunity in mosquitoes

The ISC in aedine and anopheline mosquitoes is highly conserved. Studies by Riehle and Brown [40-43] of Aedes aegypti, the yellow fever mosquito, revealed that a dose range of 1.7 – 85 μM bovine insulin stimulated ecdysteroid production by ovaries isolated from female mosquitoes. This effect was transduced through the ISC, as determined with the use of inhibitors or activators of the insulin receptor, PI-3K and Akt [40, 41]. Interestingly, the MEK inhibitor PD98059 had no effect on steroidogenesis, suggesting that the PI-3K/Akt branch of the ISC is activated for this physiological effect. Eight ILP genes have been identified in Ae. aegypti; one gene is distinctly IGF-like and expression patterns of the eight genes suggest division into growth factor and neurohormonal functions [44].

Genomic analyses of a second mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, the principal vector of malaria parasites (Plasmodium spp.) affecting humans in Africa, revealed genes encoding ILPs and proteins from both insulin signaling branches [45]. In subsequent studies, Krieger et al. [46] confirmed the existence of seven An. gambiae ILP genes, and as observed in Ae. aegypti, their developmental and tissue expression patterns have suggested specific growth factor and neuropeptide functions.

Studies with Anopheles stephensi, a major vector of human Plasmodium spp. in India and parts of the Middle East, have revealed that human insulin can induce NO synthesis in cultured cells and in the mosquito midgut [47]. Inducible NO synthesis in An. stephensi limits malaria parasite development [48] through the formation of inflammatory levels of toxic reactive nitrogen oxides [49, 50] that likely induce parasite apoptosis in the mosquito midgut lumen [51]. As such, efforts to identify parasite-derived and other inducers of AsNOS expression are significant for the development of AsNOS or associated regulatory factor genes as targets for manipulation to enhance anti-parasite resistance. In An. stephensi cells in vitro, human insulin induced AsNOS expression two-fold relative to controls at 48 h after treatment, while provision of human insulin by artificial bloodmeal induced AsNOS expression in the midgut approximately two-fold at 6 h and four-fold at 3 h post-feeding relative to controls [47]. These observations suggested that insulin control of NO synthesis and immunity is conserved between Anopheles mosquitoes and mammals.

6. Insulin signaling and its impact on malaria transmission

The relevance of insulin signaling to malaria and, ultimately to the transmission of parasites by mosquitoes, is highlighted by studies of parasite infection in mammals. Infections with Plasmodium spp. in mice [52] and humans [53-56] induce hypoglycemia, which is often predictive of severe pathology and a fatal outcome. In mice, hypoglycemia has been causally linked to hyperinsulinemia [57]. In humans, hyperinsulinemia in response to parasite infection has been reported in Thai patients [53] and also during quinine therapy [58]. Average insulin levels in hyperinsulinemic malaria patients are approximately 1.6x10-4 μM, with the highest recorded concentration at 4.7x10-4 μM [53]. These levels contrast with blood levels of insulin in healthy patients that range from a fasting concentration of 1.7x10-5 μM (0.1 ng/ml) to a non-fasting concentration of 5.9x10-4 μM (3.4 ng/ml; [59]), indicating that blood levels of insulin can vary as much as 10- to 35-fold depending on nutrition and disease status.

The dysregulation of insulin levels and glycemic status during malaria parasite infection is complex, but has been attributed, in part, to the elaboration during infection of parasite-derived glycosylphosphatidylinositol or GPI, an abundant surface protein anchor in all Plasmodium species. Although GPIs are ubiquitous on eukaryotic cells, Plasmodium GPI differs structurally from GPI found on mammalian cells [60], is produced in vast excess of its use for protein anchoring [61] and also induces pro-inflammatory responses in mammalian host cells in vitro and in vivo [62, 63]. Other studies revealed that Plasmodium GPI could induce lipogenesis and glucose oxidation in rat adipocytes and that injection of parasite GPI into mice could induce hypoglycemia [64]. These observations led to the hypothesis that Plasmodium GPIs were also insulin-mimetic. Subsequently, it was demonstrated that Plasmodium GPI exhibited signaling characteristics of the insulin extracellular mediator phosphoinositolglycan [65], which is released from host cell GPI by insulin stimulation of phosphatidylinositol-dependent phospholipase activity.

When a female mosquito ingests blood from a Plasmodium-infected host, a mix of erythrocytes, parasites, parasite-derived factors including GPI and an abundance of host-derived proteins including insulin is delivered to the midgut, a critical site for Plasmodium development in the mosquito (reviewed in [66]). After completing several stages of midgut development, malaria parasites invade the salivary glands as sporozoites, which are transmitted to the mammalian host in mosquito saliva. Parasite development requires 10 to 12 days and the average natural lifespan of An. gambiae is approximately two weeks. As such, this protracted development time presents a problem for the parasites since development and transmission must be completed before the mosquito dies or before the parasite is recognized and killed. Thus, mosquito aging and innate immunity are predicted to have significant impacts on parasite transmission.

Beier et al. [67] completed the first studies of the effects of human insulin on P. falciparum infection in An. stephensi and An. gambiae. In these studies, a high concentration of insulin (0.3 μM) was provided to adult female mosquitoes in 10% sucrose from day 0 (newly emerged adults) to day 10 after feeding on an infectious blood meal [67]. In both mosquito species, parasite infection rates were 1.5- to 1.8-fold higher and oocyst densities were significantly higher in insulin-fed relative to control groups [67], mirroring the immunosuppressive effects of insulin in mammals at high concentrations.

In more recent studies, the effects of P. falciparum GPI (PfGPI) on anti-parasite NO synthesis and signal transduction in An. stephensi have revealed that, as in mammals, parasite GPI is an important early signal for parasite infection in mosquitoes [47]. Specifically, a blood meal containing physiological levels of PfGPI, relative to a non-supplemented blood meal, induced higher levels of phosphorylation of Akt and Erk and, within 1h after feeding, induced AsNOS expression >2.5-fold in the midgut epithelium [47]. This suggests that early activation of ISC proteins contributes to the regulation of anti-parasite immunity in An. stephensi [47]. These findings, together with previous work, also indicate that insulin signaling in mosquitoes coordinately regulates immunity and at least one essential metabolic process, namely steroidogenesis, connecting evolutionary findings from model organisms to a system of significant human health importance.

In summary, current literature suggests that the ISC regulates physiological responses to oxidative stress and aging in C. elegans, D. melanogaster and mammals. Intriguing genetic correlations in nematodes suggest that insulin signaling regulation of immunity evolved in invertebrates. In mosquitoes, available data indicate that insulin signaling regulates reproduction and immunity and suggest that NO synthesis likely has multiple roles in the mosquito. At localized sites of low NO concentration, NO could facilitate signal spread to enhance the effects of ILPs on reproduction and immunity, while induction of high levels of NO and the formation of toxic nitrogen oxides [50] is consistent with an oxidative stress response that is directed toward the control of parasite infection. Limited data suggest that mosquito age does not have a significant effect on success of P. falciparum development, but a higher proportion of An. gambiae in a middle age range (4-7d) were infected relative to young (1-3d) and old (8-11d) age ranges [68]. Additional studies will be necessary to determine whether immune senescence occurs in mosquitoes as it does in fruit flies and to what extent aging in mosquitoes is regulated by insulin signaling. These studies are not only critical for our understanding of malaria parasite transmission by the insect vector, which is defined by the combined effects of age, physiological state, and immunity, but will also fill an important knowledge gap between nematodes and mammals in our understanding of the evolutionary conservation of insulin signaling.

The phenomenon of conserved of ISCs in the vertebrate and invertebrate hosts of pathogens leads to additional unanswered questions of mosquito-parasite biology. Specifically, it will be critical to determine how signals from malaria parasites, the blood meal, and the mosquito are integrated to produce a functional response. These factors, which may include parasite GPI, mammalian insulin or IGF, and mosquito NO and ILPs, may function synergistically along a dose-response continuum or they may act antagonistically so that the resource-intensive physiologies of reproduction and immunity are coordinately fine-tuned to maximize the benefits of blood feeding. Further, in mammals and nematodes, a second evolutionarily conserved growth factor signaling pathway regulated by the transforming growth factor (TGF)-βs, a large superfamily of proteins that includes growth factors and immunomodulatory cytokines, extensively intersects the insulin signaling pathway to regulate aging, oxidative stress, and immunity [69-73]. Like the insulin signaling pathway, the TGF-β signaling pathway regulates the NO-dependent immune response in An. stephensi [49, 74].

Dissecting the processes of immunity, reproduction and aging in the mosquito, therefore, will require analysis of integrated signaling pathways that coordinately regulate them. In this sense, the biology of the mosquito and, indeed, of other bloodfeeding vectors offers a unique opportunity in the animal kingdom to examine to the fullest extent the functional consequences of conserved signaling pathways that intersect across more than 600 million years of evolution.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to SL from the National Institutes of Health (AI50663, AI606640) and by a grant to MAR from the University of Arizona Institute for Collaborative Bioresearch (BIO5). We thank Dr. Mark R. Brown (University of Georgia) for his critical review of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- GRB2

growth factor receptor-bound protein 2

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor

- IIT

intensive insulin therapy

- ILP

insulin-like peptide

- IRS

insulin receptor substrate

- ISC

insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling cascade

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen-activated or extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- PDK1

phosphatidylinositol-dependent kinase 1

- PI-3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- SHC

src homology domain-containing protein

- SOS

son of sevenless protein

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Li C. The ever-expanding neuropeptide gene families in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Parasitology. 2005;131(Suppl):S109–27. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005009376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin K, Hsin H, Libina N, Kenyon C. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat Genet. 2001;28(2):139–45. doi: 10.1038/88850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogg S, Paradis S, Gottlieb S, Patterson GI, Lee L, Tissenbaum HA, Ruvkun G. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature. 1997;389(6654):994–9. doi: 10.1038/40194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, Kim DH, Sifri CD, Calderwood SB, Ruvkun G, Ausubel FM. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300(5627):1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cambi A, Figdor CG. Levels of complexity in pathogen recognition by C-type lectins. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17(4):345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, Gill MS, Walker DW, Clayton PE, Wallace DC, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR, Lithgow GJ. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289(5484):1567–9. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampayo JN, Gill MS, Lithgow GJ. Oxidative stress and aging--the use of superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics to extend lifespan. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31(Pt 6):1305–7. doi: 10.1042/bst0311305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholas HR, Hodgkin J. Responses to infection and possible recognition strategies in the innate immune system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Immunol. 2004;41(5):479–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keaney M, Matthijssens F, Sharpe M, Vanfleteren J, Gems D. Superoxide dismutase mimetics elevate superoxide dismutase activity in vivo but do not retard aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(2):239–50. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115(4):489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424(6946):277–83. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clancy DJ, Gems D, Harshman LG, Oldham S, Stocker H, Hafen E, Leevers SJ, Partridge L. Extension of life-span by loss of CHICO, a Drosophila insulin receptor substrate protein. Science. 2001;292(5514):104–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1057991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu MP, Yin CM, Tatar M. Mutations in insulin signaling pathway alter juvenile hormone synthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2005;142(3):347–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwangbo DS, Gershman B, Tu MP, Palmer M, Tatar M. Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature. 2004;429(6991):562–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broughton SJ, Piper MD, Ikeya T, Bass TM, Jacobson J, Driege Y, Martinez P, Hafen E, Withers DJ, Leevers SJ, Partridge L. Longer lifespan, altered metabolism, and stress resistance in Drosophila from ablation of cells making insulin-like ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(8):3105–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405775102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayne AC, Mockett RJ, Orr WC, Sohal RS. Enhanced catabolism of mitochondrial superoxide/hydrogen peroxide and aging in transgenic Drosophila. Biochem J. 2005;391(Pt 2):277–84. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zerofsky M, Harel E, Silverman N, Tatar M. Aging of the innate immune response in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2005;4(2):103–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2005.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spindler SR. Rapid and reversible induction of the longevity, anticancer and genomic effects of caloric restriction. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(9):960–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth GS, Mattison JA, Ottinger MA, Chachich ME, Lane MA, Ingram DK. Aging in rhesus monkeys: relevance to human health interventions. Science. 2004;305(5689):1423–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1102541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katic M, Kahn CR. The role of insulin and IGF-1 signaling in longevity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(3):320–43. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baba T, Shimizu T, Suzuki Y, Ogawara M, Isono K, Koseki H, Kurosawa H, Shirasawa T. Estrogen, insulin, and dietary signals cooperatively regulate longevity signals to enhance resistance to oxidative stress in mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):16417–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, Treuting P, Ogburn CE, Emond M, Coskun PE, Ladiges W, Wolf N, Van Remmen H, Wallace DC, Rabinovitch PS. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science. 2005;308(5730):1909–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1106653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heemskerk VH, Daemen MA, Buurman WA. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and growth hormone (GH) in immunity and inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perdue JF. Chemistry, structure, and function of insulin-like growth factors and their receptors: a review. Can J Biochem Cell Biol. 1984;62(11):1237–45. doi: 10.1139/o84-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helderman JH, Pietri AO, Raskin P. In vitro control of T-lymphocyte insulin receptors by in vivo modulation of insulin. Diabetes. 1983;32(8):712–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.32.8.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue T, Saito H, Matsuda T, Fukatsu K, Han I, Furukawa S, Ikeda S, Muto T. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor I augment bactericidal capacity of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Shock. 1998;10(4):278–84. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renier G, Clement I, Desfaits AC, Lambert A. Direct stimulatory effect of insulin-like growth factor-I on monocyte and macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production. Endocrinology. 1996;137(11):4611–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt P, Eardley DD. Suppressive effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1) on immune responses. J Immunol. 1986;136(11):3994–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dandona P, Mohanty P, Chaudhuri A, Garg R, Aljada A. Insulin infusion in acute illness. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2069–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI26045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen TK, Thiel S, Wouters PJ, Christiansen JS, Van den Berghe G. Intensive insulin therapy exerts anti-inflammatory effects in critically ill patients and counteracts the adverse effect of low mannose-binding lectin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(3):1082–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li G, Barrett EJ, Wang H, Chai W, Liu Z. Insulin at physiological concentrations selectively activates insulin but not insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) or insulin/IGF-I hybrid receptors in endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(11):4690–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang FC. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(10):820–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwase K, Miyanaka K, Shimizu A, Nagasaki A, Gotoh T, Mori M, Takiguchi M. Induction of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in rat brain astrocytes by systemic lipopolysaccharide treatment. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(16):11929–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quintana E, Hernandez C, Moran AP, Esplugues JV, Barrachina MD. Transcriptional up-regulation of nNOS in the dorsal vagal complex during low endotoxemia. Life Sci. 2005;77(9):1044–54. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan SH, Wang LL, Wang SH, Chan JY. Differential cardiovascular responses to blockade of nNOS or iNOS in rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133(4):606–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shankar R, Zhu JS, Ladd B, Henry D, Shen HQ, Baron AD. Central nervous system nitric oxide synthase activity regulates insulin secretion and insulin action. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(7):1403–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begum N, Ragolia L. High glucose and insulin inhibit VSMC MKP-1 expression by blocking iNOS via p38 MAPK activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278(1):C81–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.1.C81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SJ, Chun JY, Kim MS. Insulin stimulates production of nitric oxide via Erk in osteoblast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278(3):712–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konopatskaya O, Shore AC, Tooke JE, Whatmore JL. A role for heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins and Erk 1/2 in insulin-mediated, nitric-oxide-dependent, cyclic GMP production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Diabetologia. 2005;48(3):595–604. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riehle MA, Brown MR. Insulin stimulates ecdysteroid production through a conserved signaling cascade in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;29(10):855–60. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(99)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riehle MA, Brown MR. Insulin receptor expression during development and a reproductive cycle in the ovary of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;308(3):409–20. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riehle MA, Brown MR. Molecular analysis of the serine/threonine kinase Akt and its expression in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12(3):225–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Q, Brown MR. Signaling and function of insulin-like peptides in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riehle MA, Fan Y, Cao C, Brown MR. Molecular characterization of insulin-like peptides in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti: Expression, cellular localization, and phylogeny. Peptides. 2006 Aug 23; doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.016. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riehle MA, Garczynski SF, Crim JW, Hill CA, Brown MR. Neuropeptides and peptide hormones in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298(5591):172–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1076827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger MJ, Jahan N, Riehle MA, Cao C, Brown MR. Molecular characterization of insulin-like peptide genes and their expression in the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2004;13(3):305–15. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim J, Gowda DC, Krishnegowda G, Luckhart S. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in Anopheles stephensi by Plasmodium falciparum: mechanism of signaling and the role of parasite glycosylphosphatidylinositols. Infect Immun. 2005;73(5):2778–89. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2778-2789.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luckhart S, Vodovotz Y, Cui L, Rosenberg R. The mosquito Anopheles stephensi limits malaria parasite development with inducible synthesis of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(10):5700–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luckhart S, Crampton AL, Zamora R, Lieber MJ, Dos Santos PC, Peterson TM, Emmith N, Lim J, Wink DA, Vodovotz Y. Mammalian transforming growth factor beta1 activated after ingestion by Anopheles stephensi modulates mosquito immunity. Infect Immun. 2003;71(6):3000–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3000-3009.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson TML, Gow AJ, Luckhart S. Nitric oxide metabolites induced in Anopheles stephensi control malaria parasite infection. Free Rad Biol Med. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.037. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hurd H, Carter V. The role of programmed cell death in Plasmodium-mosquito interactions. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34(1314):1459–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elased K, Playfair JH. Hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in rodent models of severe malaria infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62(11):5157–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5157-5160.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White NJ, Warrell DA, Chanthavanich P, Looareesuwan S, Warrell MJ, Krishna S, Williamson DH, Turner RC. Severe hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(2):61–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307143090201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White NJ, Miller KD, Marsh K, Berry CD, Turner RC, Williamson DH, Brown J. Hypoglycaemia in African children with severe malaria. Lancet. 1987;1(8535):708–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips RE. Hypoglycaemia is an important complication of falciparum malaria. Q J Med. 1989;71(266):477–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Atabani GS, Saeed BO, elSeed BA, Bayoumi MA, Hadi NH, Abu-Zeid YA, Bayoumi RA. Hypoglycaemia in Sudanese children with cerebral malaria. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66(774):326–7. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.774.326-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elased KM, Playfair JH. Reversal of hypoglycaemia in murine malaria by drugs that inhibit insulin secretion. Parasitology. 1996;112(Pt 6):515–21. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phillips RE, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Chanthavanich P, Karbwang J, Supanaranond W, Turner RC, Warrell DA. Hypoglycaemia and antimalarial drugs: quinidine and release of insulin. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292(6531):1319–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6531.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darby SM, Miller ML, Allen RO, LeBeau M. A mass spectrometric method for quantitation of intact insulin in blood samples. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;25(1):8–14. doi: 10.1093/jat/25.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gowda DC. Structure and activity of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors of Plasmodium falciparum. Microbes Infect. 2002;4(9):983–90. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01619-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferguson MA, Brimacombe JS, Cottaz S, Field RA, Guther LS, Homans SW, McConville MJ, Mehlert A, Milne KG, Ralton JE, et al. Glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol molecules of the parasite and the host. Parasitology. 1994;108(Suppl):S45–54. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000075715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu J, Krishnegowda G, Gowda DC. Induction of proinflammatory responses in macrophages by the glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum: the requirement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase, p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and NF-kappaB pathways for the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(9):8617–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413539200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krishnegowda G, Hajjar AM, Zhu J, Douglass EJ, Uematsu S, Akira S, Woods AS, Gowda DC. Induction of proinflammatory responses in macrophages by the glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum: cell signaling receptors, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) structural requirement, and regulation of GPI activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(9):8606–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413541200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schofield L, Hackett F. Signal transduction in host cells by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol toxin of malaria parasites. J Exp Med. 1993;177(1):145–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caro HN, Sheikh NA, Taverne J, Playfair JH, Rademacher TW. Structural similarities among malaria toxins insulin second messengers, and bacterial endotoxin. Infect Immun. 1996;64(8):3438–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3438-3441.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whitten MM, Shiao SH, Levashina EA. Mosquito midguts and malaria: cell biology, compartmentalization and immunology. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28(4):121–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beier MS, Pumpuni CB, Beier JC, Davis JR. Effects of para-aminobenzoic acid, insulin, and gentamicin on Plasmodium falciparum development in anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1994;31(4):561–5. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okech BA, Gouagna LC, Kabiru EW, Beier JC, Yan G, Githure JI. Influence of age and previous diet of Anopheles gambiae on the infectivity of natural Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes from human volunteers. J Insect Sci. 2004;4:33. doi: 10.1093/jis/4.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carrieri G, Marzi E, Olivieri F, Marchegiani F, Cavallone L, Cardelli M, Giovagnetti S, Stecconi R, Molendini C, Trapassi C, De Benedictis G, Kletsas D, Franceschi C. The G/C915 polymorphism of transforming growth factor beta1 is associated with human longevity: a study in Italian centenarians. Aging Cell. 2004;3(6):443–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Capri M, Salvioli S, Sevini F, Valensin S, Celani L, Monti D, Pawelec G, De Benedictis G, Gonos ES, Franceschi C. The genetics of human longevity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1067:252–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carmona-Cuenca I, Herrera B, Ventura JJ, Roncero C, Fernandez M, Fabregat I. EGF blocks NADPH oxidase activation by TGF-beta in fetal rat hepatocytes, impairing oxidative stress, and cell death. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207(2):322–30. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AK, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:99–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Danielpour D, Song K. Cross-talk between IGF-I and TGF-beta signaling pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17(12):59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vodovotz Y, Zamora R, Lieber MJ, Luckhart S. Cross-talk between nitric oxide and transforming growth factor-beta1 in malaria. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4(7):787–97. doi: 10.2174/1566524043359999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]