Abstract

To comprehend the multipartite organization of large-scale biological and social systems, we introduce an information theoretic approach that reveals community structure in weighted and directed networks. We use the probability flow of random walks on a network as a proxy for information flows in the real system and decompose the network into modules by compressing a description of the probability flow. The result is a map that both simplifies and highlights the regularities in the structure and their relationships. We illustrate the method by making a map of scientific communication as captured in the citation patterns of >6,000 journals. We discover a multicentric organization with fields that vary dramatically in size and degree of integration into the network of science. Along the backbone of the network—including physics, chemistry, molecular biology, and medicine—information flows bidirectionally, but the map reveals a directional pattern of citation from the applied fields to the basic sciences.

Keywords: clustering, compression, information theory, map of science, bibiometrics

Biological and social systems are differentiated, multipartite, integrated, and dynamic. Data about these systems, now available on unprecedented scales, often are schematized as networks. Such abstractions are powerful (1, 2), but even as abstractions they remain highly complex. It therefore is helpful to decompose the myriad nodes and links into modules that represent the network (3–5). A cogent representation will retain the important information about the network and reflect the fact that interactions between the elements in complex systems are weighted, directional, interdependent, and conductive. Good representations both simplify and highlight the underlying structures and the relationships that they depict; they are maps (6, 7).

To create a good map, the cartographer must attain a fine balance between omitting important structures by oversimplification and obscuring significant relationships in a barrage of superfluous detail. The best maps convey a great deal of information but require minimal bandwidth: the best maps are also good compressions. By adopting an information-theoretic approach, we can measure how efficiently a map represents the underlying geography, and we can measure how much detail is lost in the process of simplification, which allows us to quantify and resolve the cartographer's tradeoff.

Network Maps and Coding Theory

In this article, we use maps to describe the dynamics across the links and nodes in directed, weighted networks that represent the local interactions among the subunits of a system. These local interactions induce a system-wide flow of information that characterizes the behavior of the full system (8–12). Consequently, if we want to understand how network structure relates to system behavior, we need to understand the flow of information on the network. We therefore identify the modules that compose the network by finding an efficiently coarse-grained description of how information flows on the network. A group of nodes among which information flows quickly and easily can be aggregated and described as a single well connected module; the links between modules capture the avenues of information flow between those modules.

Succinctly describing information flow is a coding or compression problem. The key idea in coding theory is that a data stream can be compressed by a code that exploits regularities in the process that generates the stream (13). We use a random walk as a proxy for the information flow, because a random walk uses all of the information in the network representation and nothing more. Thus, it provides a default mechanism for generating a dynamics from a network diagram alone (8).

Taking this approach, we develop an efficient code to describe a random walk on a network. We thereby show that finding community structure in networks is equivalent to solving a coding problem (14–16). We exemplify this method by making a map of science, based on how information flows among scientific journals by means of citations.

Describing a Path on a Network.

To illustrate what coding has to do with map-making, consider the following communication game. Suppose that you and I both know the structure of a weighted, directed network. We aim to choose a code that will allow us to efficiently describe paths on the network that arise from a random walk process in a language that reflects the underlying structure of the network. How should we design our code?

If maximal compression were our only objective, we could encode the path at or near the entropy rate of the corresponding Markov process. Shannon showed that one can achieve this rate by assigning to each node a unique dictionary over the outgoing transitions (17). But compression is not our only objective; here, we want our language to reflect the network structure, we want the words we use to refer to things in the world. Shannon's approach does not do this for us because every codeword would have a different meaning depending on where it is used. Compare maps: useful maps assign unique names to important structures. Thus, we seek a way of describing or encoding the random walk in which important structures indeed retain unique names. Let us look at a concrete example. Fig. 1A shows a weighted network with n = 25 nodes. The link thickness indicates the relative probability that a random walk will traverse any particular link. Overlaid on the network is a specific 71-step realization of a random walk that we will use to illustrate our communication game. In Fig. 1, we describe this walk with increasing levels of compression (B–D), exploiting more and more of the regularities in the network.

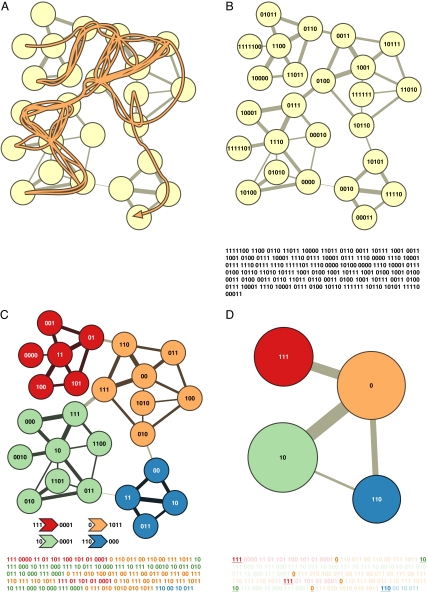

Fig. 1.

Detecting communities by compressing the description of information flows on networks. (A) We want to describe the trajectory of a random walk on the network such that important structures have unique names. The orange line shows one sample trajectory. (B) A basic approach is to give a unique name to every node in the network. The Huffman code illustrated here is an efficient way to do so. The 314 bits shown under the network describe the sample trajectory in A, starting with 1111100 for the first node on the walk in the upper left corner, 1100 for the second node, etc., and ending with 00011 for the last node on the walk in the lower right corner. (C) A two-level description of the random walk, in which major clusters receive unique names, but the names of nodes within clusters are reused, yields on average a 32% shorter description for this network. The codes naming the modules and the codes used to indicate an exit from each module are shown to the left and the right of the arrows under the network, respectively. Using this code, we can describe the walk in A by the 243 bits shown under the network in C. The first three bits 111 indicate that the walk begins in the red module, the code 0000 specifies the first node on the walk, etc. (D) Reporting only the module names, and not the locations within the modules, provides an efficient coarse graining of the network.

Huffman Coding.

A straightforward method of giving names to nodes is to use a Huffman code (18). Huffman codes save space by assigning short codewords to common events or objects and long codewords to rare ones, much as common words are short in spoken languages (19). Fig. 1B shows a prefix-free Huffman coding for our sample network. Each codeword specifies a particular node, and the codeword lengths are derived from the ergodic node visit frequencies of an infinitely long random walk. With the Huffman code pictured in Fig. 1B, we are able to describe the specific 71-step walk in 314 bits. If we instead had chosen a uniform code, in which all codewords are of equal length, each codeword would be  log 25

log 25 = 5 bits long and 71·5 = 355 bits would have been required to describe the walk.

= 5 bits long and 71·5 = 355 bits would have been required to describe the walk.

Although in this example we assign actual codewords to the nodes for illustrative purposes, in general, we will not be interested in the codewords themselves but rather in the theoretical limit of how concisely we can specify the path. Here, we invoke Shannon's source coding theorem (17), which implies that when you use n codewords to describe the n states of a random variable X that occur with frequencies pi, the average length of a codeword can be no less than the entropy of the random variable X itself: H(X) = −Σ1n pi log(pi). This theorem provides us with the necessary apparatus to see that, in our Huffman illustration, the average number of bits needed to describe a single step in the random walk is bounded below by the entropy H(P), where P is the distribution of visit frequencies to the nodes on the network. We define this lower bound on code length to be L. For example, L = 4.50 bits per step in Fig. 1B.

Highlighting Important Objects.

Matching the length of codewords to the frequencies of their use gives us efficient codewords for the nodes, but no map. Merely assigning appropriate-length names to the nodes does little to simplify or highlight aspects of the underlying structure. To make a map, we need to separate the important structures from the insignificant details. We therefore divide the network into two levels of description. We retain unique names for large-scale objects, the clusters or modules to be identified within our network, but we reuse the names associated with fine-grain details, the individual nodes within each module. This is a familiar approach for assigning names to objects on maps: most U.S. cities have unique names, but street names are reused from one city to the next, such that each city has a Main Street and a Broadway and a Washington Avenue and so forth. The reuse of street names rarely causes confusion, because most routes remain within the bounds of a single city.

A two-level description allows us to describe the path in fewer bits than we could do with a one-level description. We capitalize on the network's structure and, in particular, on the fact that a random walker is statistically likely to spend long periods of time within certain clusters of nodes. Fig. 1C illustrates this approach. We give each cluster a unique name but use a different Huffman code to name the nodes within each cluster. A special codeword, the exit code, is chosen as part of the within-cluster Huffman coding and indicates that the walk is leaving the current cluster. The exit code always is followed by the “name” or module code of the new module into which the walk is moving [see supporting information (SI) for more details]. Thus, we assign unique names to coarse-grain structures (the cities in the city metaphor) but reuse the names associated with fine-grain details (the streets in the city metaphor). The savings are considerable; in the two-level description of Fig. 1C the limit L is 3.05 bits per step compared with 4.50 for the one-level description.

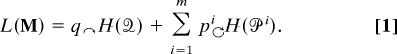

Herein lies the duality between finding community structure in networks and the coding problem: to find an efficient code, we look for a module partition M of n nodes into m modules so as to minimize the expected description length of a random walk. By using the module partition M, the average description length of a single step is given by

|

This equation comprises two terms: first is the entropy of the movement between modules, and second is the entropy of movements within modules (where exiting the module also is considered a movement). Each is weighted by the frequency with which it occurs in the particular partitioning. Here, q↷ is the probability that the random walk switches modules on any given step. H(𝒬) is the entropy of the module names, i.e., the entropy of the underlined codewords in Fig. 1D. H(𝒫i) is the entropy of the within-module movements, including the exit code for module i. The weight p i is the fraction of within-module movements that occur in module i, plus the probability of exiting module i such that Σi=1m p

i is the fraction of within-module movements that occur in module i, plus the probability of exiting module i such that Σi=1m p i = 1 + q↷ (see SI for more details).

i = 1 + q↷ (see SI for more details).

For all but the smallest networks, it is infeasible to check all possible partitions to find the one that minimizes the description length in the map equation (Eq. 1). Instead, we use computational search. We first compute the fraction of time each node is visited by a random walker using the power method, and, using these visit frequencies, we explore the space of possible partitions by using a deterministic greedy search algorithm (20, 21). We refine the results with a simulated annealing approach (6) using the heat-bath algorithm (see SI for more details).

Fig. 1D shows the map of the network, with the within-module descriptors faded out; here the significant objects have been highlighted and the details have been filtered away.

In the interest of visual simplicity, the illustrative network in Fig. 1 has weighted but undirected links. Our method is developed more generally, so that we can extract information from networks with links that are directed in addition to being weighted. The map equation remains the same; only the path that we aim to describe must be slightly modified to achieve ergodicity. We introduce a small “teleportation probability” τ in the random walk: with probability τ, the process jumps to a random node anywhere in the network, which converts our random walker into the sort of “random surfer” that drives Google's PageRank algorithm (22). Our clustering results are highly robust to the particular choice of the small fraction τ. For example, so long as τ < 0.45 the optimal partitioning of the network in Fig. 1 remains exactly the same. In general, the more significant the regularities, the higher τ can be before frequent teleportation swamps the network structure. We choose τ = 0.15 corresponding to the well known damping factor d = 0.85 in the PageRank algorithm (22).

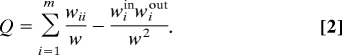

Mapping Flow Compared with Maximizing Modularity

The traditional way of identifying community structure in directed and weighted networks has been simply to disregard the directions and the weights of the links. But such approaches discard valuable information about the network structure. By mapping the system-wide flow induced by local interactions between nodes, we retain the information about the directions and the weights of the links. We also acknowledge their interdependence in networks inherently characterized by flows. This distinction makes it interesting to compare our flow-based approach with recent topological approaches based on modularity optimization that also makes use of information about weight and direction (23–26). In its most general form, the modularity for a given partitioning of the network into m modules is the sum of the total weight of all links in each module minus the expected weight

|

Here, wii is the total weight of links starting and ending in module i, wiin and wiout are the total in- and out-weight of links in module i, and w is the total weight of all links in the network. To estimate the community structure in a network, Eq. 2 is maximized over all possible assignments of nodes into any number m of modules. Eqs. 1 and 2 reflect two different senses of what it means to have a network. The former, which we pursue here, finds the essence of a network in the patterns of flow that its structure induces. The latter effectively situates the essence of network in the topological properties of its links (as we did in ref. 16).

Does this conceptual distinction make any practical difference? Fig. 2 illustrates two simple networks for which the map equation and modularity give different partitionings. The weighted, directed links shown in the network in Fig. 2A induce a structured pattern of flow with long persistence times in, and limited flow between, the four clusters as highlighted on the left. The map equation picks up on these structural regularities, and thus the description length is much shorter for the partitioning in Fig. 2A Left (2.67 bits per step) than for Fig. 2A Right (4.13 bits per step). Modularity is blind to the interdependence in networks characterized by flows and thus cannot pick up on this type of structural regularity. It only counts weights of links, in-degree, and out-degree in the modules, and thus prefers to partition the network as shown in Fig. 2A Right with the heavily weighted links inside of the modules.

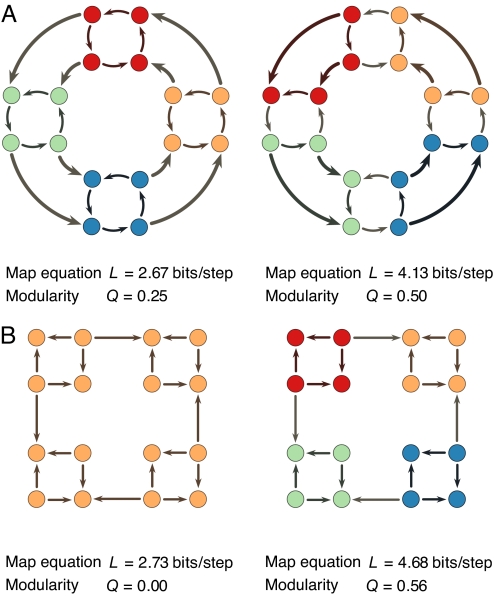

Fig. 2.

Mapping flow highlights different aspects of structure than does optimizing modularity in directed and weighted networks. The coloring of nodes illustrates alternative partitions of two sample networks. (Left) Partitions show the modular structure as optimized by the map equation (minimum L). (Right) Partitions show the structure as optimized by modularity (maximum Q). In the network shown in A, the left-hand partition minimizes the map equation because the persistence times in the modules are long; with the weight of the bold links set to twice the weight of other links, a random walker without teleportation takes on average three steps in a module before exiting. The right-hand clustering gives a longer description length because a random walker takes on average only 12/5 steps in a module before exiting. The right-hand clustering maximizes the modularity because modularity counts weights of links, the in-degree, and the out-degree in the modules; the right-hand partitioning places the heavily weighted links inside of the modules. In B, for the same reason, the right-hand partition again maximizes modularity, but not so the map equation. Because every node is either a sink or a source in this network, the links do not induce any long-range flow, and the one-step walks are best described as in the left-hand partition, with all nodes in the same cluster.

In Fig. 2B, by contrast, there is no pattern of extended flow at all. Every node is either a source or a sink, and no movement along the links on the network can exceed more than one step in length. As a result, random teleportation will dominate (irrespective of teleportation rate), and any partition into multiple modules will lead to a high flow between the modules. For a network such as in Fig. 2B, where the links do not induce a pattern of flow, the map equation always will partition the network into one single module. Modularity, because it looks at pattern in the links and in- and out-degree, separates the network into the clusters shown at right.

Which method should a researcher use? It depends on which of the two senses of network, described above, that the researcher is studying. For analyzing network data where links represent patterns of movement among nodes, flow-based approaches such as the map equation are likely to identify the most important aspects of structure. For analyzing network data where links represent not flows but rather pairwise relationships, it may be useful to detect structure even where no flow exists. For these systems, topological methods such as modularity (11) or cluster-based compression (16) may be preferable.

Mapping Scientific Communication

Science is a highly organized and parallel human endeavor to find patterns in nature; the process of communicating research findings is as essential to progress as is the act of conducting the research in the first place. Thus, science is not merely a set of ideas but also the flow of these ideas through a multipartite and highly differentiated social system. Citation patterns among journals allow us to glimpse this flow and provide the trace of communication between scientists (27–31). To highlight important fields and their relationships, to uncover differences and changes, to simplify and make the system comprehensible—we need a good map of science.

Using the information theoretic approach presented above, we map the flow of citations among 6,128 journals in the sciences (Fig. 3) and social sciences (Fig. 4). The 6,434,916 citations in this cross-citation network represent a trace of the scientific activity during 2004 (32). Our data tally on a journal-by-journal basis the citations from articles published in 2004 to articles published in the previous 5 years. We exclude journals that publish <12 articles per year and those that do not cite other journals within the data set. We also exclude the only three major journals that span a broad range of scientific disciplines: Science, Nature, and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; the broad scope of these journals otherwise creates an illusion of tighter connections among disciplines, when in fact few readers of the physics articles in Science also are close readers of the biomedical articles therein. Because we are interested in relationships between journals, we also exclude journal self-citations.

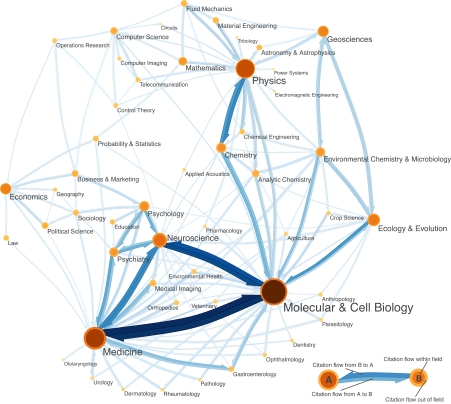

Fig. 3.

A map of science based on citation patterns. We partitioned 6,128 journals connected by 6,434,916 citations into 88 modules and 3,024 directed and weighted links. For visual simplicity, we show only the links that the random surfer traverses >1/5,000th of her time, and we only show the modules that are visited via these links (see SI for the complete list). Because of the automatic ranking of nodes and links by the random surfer (22), we are assured of showing the most important links and nodes. For this particular level of detail, we capture 98% of the node weights and 94% of all flow.

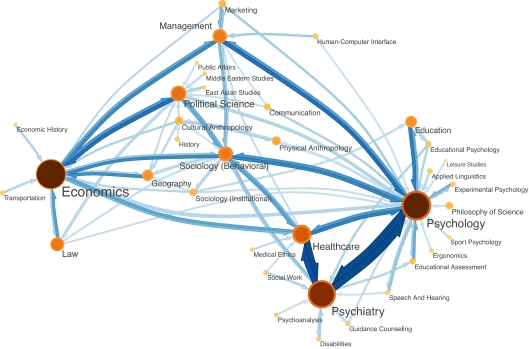

Fig. 4.

A map of the social sciences. The journals listed in the 2004 social science edition of Journal Citation Reports (32) are a subset of those illustrated in Fig. 3, totaling 1,431 journals and 217,287 citations. When we map this subset on its own, we get a finer level of resolution. The 10 modules that correspond to the social sciences now are partitioned into 54 modules, but for simplicity we show only links that the random surfer visits at least 1/2,000th of her times together with the modules they connect (see SI for the complete list). For this particular level of detail, we capture 97% of the node weights and 90% of all flow.

Through the operation of our algorithm, the fields and the boundaries between them emerge directly from the citation data rather than from our preconceived notions of scientific taxonomy (see Figs. 3 and 4). Our only subjective contribution has been to suggest reasonable names for each cluster of journals that the algorithm identifies: economics, mathematics, geosciences, and so forth.

The physical size of each module or “field” on the map reflects the fraction of time that a random surfer spends following citations within that module. Field sizes vary dramatically. Molecular biology includes 723 journals that span the areas of genetics, cell biology, biochemistry, immunology, and developmental biology; a random surfer spends 26% of her time in this field, indicated by the size of the module. Tribology (the study of friction) includes only seven journals, in which a random surfer spends 0.064% of her time.

The weighted and directed links between fields represent citation flow, with the color and width of the arrows indicating flow volume. The heavy arrows between medicine and molecular biology indicate a massive traffic of citations between these disciplines. The arrows point in the direction of citation: A → B means “A cites B” as shown in the key. These directed links reveal the relationship between applied and basic sciences. We find that the former cite the latter extensively, but the reverse is not true, as we see, for example, with geotechnology citing geosciences, plastic surgery citing general medicine, and power systems citing general physics. The thickness of the module borders reflect the probability that a random surfer within the module will follow a citation to a journal outside of the module. These outflows show a large variation; for example the outflow is 30% in general medicine but only 12% in economics.

The map reveals a ring-like structure in which all major disciplines are connected to one another by chains of citations, but these connections are not always direct because fields on opposite sides of the ring are linked only through intermediate fields. For example, although psychology rarely cites general physics or vice versa, psychology and general physics are connected via the strong links to and between the intermediaries molecular biology and chemistry. Once we consider the weights of the links among fields, however, it becomes clear that the structure of science is more like the letter U than like a ring, with the social sciences at one terminal and engineering at the other, joined mainly by a backbone of medicine, molecular biology, chemistry, and physics. Because our map shows the pattern of citations to research articles published within 5 years, it represents what de Solla Price called the “research frontier” (27) rather than the long-term interdependencies among fields. For example, although mathematics are essential to all natural sciences, the field of mathematics is not central in our map because only certain subfields (e.g., areas of physics and statistics) rely heavily on the most recent developments in pure mathematics and contribute in return to the research agenda in that field.

When a cartographer designs a map, the scale or scope of the map influences the choice of which objects are represented. A regional map omits many of the details that appear on a city map. Similarly, in the approach that we have developed here, the appropriate size or resolution of the modules depends on the universe of nodes that are included in the network. If we compare the map of a network to a map of a subset of the same network, we would expect to see the map of the subset reveal finer divisions, with modules composed of fewer nodes. Fig. 4 illustrates this by partitioning a subset of the journals included in the map of science: the 1,431 journals in the social sciences. The basic structure of the fields and their relations remains unchanged, with psychiatry and psychology linked via sociology and management to economics and political science, but the map also reveals further details. Anthropology fractures along the physical/cultural divide. Sociology divides into behavioral and institutional clusters. Marketing secedes from management. Psychology and psychiatry reveal a set of applied subdisciplines.

The additional level of detail in the more narrowly focused map would have been clutter on the full map of science. When we design maps to help us comprehend the world, we must find that balance where we eliminate extraneous detail but highlight the relationships among important structures. Here, we have shown how to formalize this cartographer's precept by using the mathematical apparatus of information theory.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We are grateful to Jevin West for processing the data used to construct the maps in Figs. 3 and 4 and to Cynthia A. Brewer, www.ColorBrewer.org, for providing the color schemes we have used in Figs. 1–4. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study Program Cooperative Agreement 5U01GM07649.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0706851105/DC1.

References

- 1.Newman MEJ. SIAM Review. 2003;45:167–256. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman MEJ, Barabási AL, Watts DJ. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girvan M, Newman MEJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7821–7826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122653799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palla G, Derényi I, Farkas I, Vicsek T. Nature. 2005;435:814–818. doi: 10.1038/nature03607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sales-Pardo M, Guimerà R, Moreira AA, Amaral LAN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703740104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guimerà R, Amaral LAN. Nature. 2005;433:895–900. doi: 10.1038/nature03288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tufte ER. Beautiful Evidence. Cheshire, CT: Graphics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziv E, Middendorf M, Wiggins CH. Phys Rev E. 2005;71:046117. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.046117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donath WE, Hoffman A. IBM Tech Discl Bull. 1972;15:938–944. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman MEJ, Girvan M. Phys Rev E. 2004;69:026113. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.026113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eriksen KA, Simonsen I, Maslov S, Sneppen K. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90:148701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.148701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon CE, Weaver W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Champaign, IL: Univ of Illinois Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rissanen J. Automatica. 1978;14:465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grünwald P, Myung IJ, Pitt M, editors. Advances in Minimum Description Length: Theory and Applications. London: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosvall M, Bergstrom CT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7327–7331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611034104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon CE. Bell Labs Tech J. 1948;27:379–423. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huffman D. Proc Inst Radio Eng. 1952;40:1098–1102. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zipf GK. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort: An Introduction to Human Ecology. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clauset A, Newman MEJ, Moore C. Phys Rev E. 2004;70:066111. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.066111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakita K, Tsurumi T. 2007;arXiv:cs/0702048. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brin S, Page L. Comp Networks ISDN Sys. 1998;33:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman MEJ. Phys Rev E. 2004;69:066133. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guimerà R, Sales-Pardo M, Amaral LAN. Phys Rev E. 2007;76:036102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.036102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leicht EA, Newman MEJ. 2007;arXiv:0709.4500. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arenas A, Duch J, Fernández A, Gómez S. New J Phys. 2007;9:176. [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Solla Price DJ. Science. 1965;149:510–515. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3683.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Small H. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1973;24:265–269. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Small H. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1999;50:799–813. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moya-Anegón F, Vargas-Quesada1 B, Herrero-Solana V, Chinchilla-Rodríguez Z, Corera-Álvarez E, Munoz-Fernández FJ. Scientometrics. 2004;61:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiffrin RM, Börner K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5183–5185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307852100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute for Scientific Information. Journal Citation Reports. Philadelphia, PA: Thompson Scientific; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.