Abstract

Products of the umuD gene in Escherichia coli play key roles in coordinating the switch from accurate DNA repair to mutagenic translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) during the SOS response to DNA damage. Homodimeric UmuD2 is up-regulated 10-fold immediately after damage, after which slow autocleavage removes the N-terminal 24 amino acids of each UmuD. The remaining fragment, UmuD′2, is required for mutagenic TLS. The small proteins UmuD2 and UmuD′2 make a large number of specific protein–protein contacts, including three of the five known E. coli DNA polymerases, parts of the replication machinery, and RecA recombinase. We show that, despite forming stable homodimers, UmuD2 and UmuD′2 have circular dichroism (CD) spectra with almost no α-helix or β-sheet signal at physiological concentrations in vitro. High protein concentrations, osmolytic crowding agents, and specific interactions with a partner protein can produce CD spectra that resemble the expected β-sheet signature. A lack of secondary structure in vitro is characteristic of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), many of which act as regulators. A stable homodimer that lacks significant secondary structure is unusual but not unprecedented. Furthermore, previous single-cysteine cross-linking studies of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 show that they have a nonrandom structure at physiologically relevant concentrations in vitro. Our results offer insights into structural characteristics of relatively poorly understood IDPs and provide a model for how the umuD gene products can regulate diverse aspects of the bacterial SOS response.

Keywords: natively unfolded, SOS response, unstructured, denatured, DNA repair

The bacterial SOS response is a tightly regulated reaction to stress-induced DNA damage (1). It is temporally divided into an early, relatively accurate DNA repair phase and a later, more mutagenic damage-tolerance phase (2). This timing is regulated in part by products of the umuD gene. The initial product, UmuD2, is a homodimer composed of 139 amino acid subunits that appears early after SOS induction (2). Damage-induced RecA:ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments mediate a slow autocleavage of UmuD2 that is mechanistically similar to the inactivation of the LexA repressor (3). The N-terminal 24 amino acids of each subunit of UmuD2 are removed, leaving a homodimer of the C-terminal 115 amino acid subunits, UmuD′2 (3). UmuD′2 activates UmuC, the catalytic subunit of the Y family DNA polymearse (Pol) V, for mutagenic translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) (4–6).

For such small proteins, UmuD2 and UmuD′2 make a remarkable number of specific protein–protein contacts, many, but not all, of them to DNA polymerases. Both proteins have been shown to interact with UmuC (5), DinB (the Y family DNA Pol IV) (7), and three subunits of the replicative DNA Pol III (8). Additionally, both interact with RecA:ssDNA nucleoprotein filaments (3, 9).

However, despite the nearly identical primary structures of UmuD2 and UmuD′2, their interactions with the same partner can differ in affinity and functional significance. Only UmuD2 prevents DinB-induced -1 frame shifts (7), whereas only UmuD′2 activates UmuC for TLS (4–6). UmuD2 interacts preferentially with the β-processivity subunit of Pol III, whereas UmuD′2 favors the α-catalytic subunit (8). RecA:ssDNA interacts with UmuD2 to promote cleavage to UmuD′2 (3), whereas UmuD′2C requires trans RecA:ssDNA for efficient TLS (9). UmuD2 may be degraded by either Lon (10) or ClpXP proteases (11), whereas UmuD′2 must first exchange into the UmuD′D heterodimer to be degraded by ClpXP (12). The fact that such small proteins (no more than 30 kDa as dimers) can make so many specific protein–protein interactions is intriguing, and high-resolution structural studies were undertaken in an effort to find an explanation.

The x-ray (13) and NMR (14) structures of the cleaved form, UmuD′2, offer some insight. Although both methods indicate that UmuD′2 has an overall β-sheet fold, a detailed comparison between the two structures reveals substantial differences (14). The shape of the protein is less globular in the NMR structure (14), and the protease active site residues are only poised for catalysis in the x-ray structure (13). The structural differences suggest that UmuD′2 may have considerable plasticity.

Although no high-resolution structural data are available for UmuD2, we have recently proposed four energy-minimized symmetrical models of UmuD2 (15). Previous single-cysteine studies of UmuD2, which probed the structure of UmuD2 in solution at physiologically relevant concentrations, have generally been consistent with our structural models. Single-cysteine derivatives of many amino acids that are predicted to be close to the dimer interface robustly cross-link to covalent dimers (16, 17). Interestingly, some positions that are predicted to be far away from the dimer interface also cross-link (16, 18). However, these residues can come together if the N-terminal arms are in an intermediate conformation (15). These results suggest that UmuD2 may interchange among multiple conformations in solution.

We used circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to compare the secondary structure of UmuD2 with that of the known β-sheet protein UmuD′2, but we were surprised that, at physiological concentrations, both protein spectra resemble a random coil more than the expected β-sheet. These results are typical of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), which have significantly less secondary or tertiary structure in vitro than other proteins (19–28). This class of proteins has been previously called natively denatured, natively unfolded, and intrinsically unstructured, among other names (21). Examples of these proteins include proteases, signaling factors, and other protein and nucleic acid-binding proteins (20, 24). IDPs often have important roles in regulation because of an ability to alter their precise structure, and therefore they function in response to changes in the cellular environment (25). Many of these proteins obtain more typical secondary structure in vivo, although some remain disordered (22, 23). The actual structure of an IDP is poorly understood, although a completely random and extended structure is probably rare (19, 27).

Unlike most previously characterized IDPs, UmuD2 and UmuD′2 form stable homodimers at a wide range of concentrations in vitro. Additionally, previous single-cysteine studies show that both proteins have a nonrandom structure at physiological concentrations (16–18, 29). Our results provide a rare opportunity to probe the actual structure of proteins that appear unfolded by CD spectroscopy.

Results

UmuD2 and UmuD′2 Have Extremely Different CD Spectra at μM and mM Concentrations.

As part of our effort to compare the undetermined structure of UmuD2 to the known structure of its derivative UmuD′2 (13, 14), we measured the CD spectrum of UmuD′2 at 5 μM, which is the concentration found in SOS-induced cells (7). We were startled to discover that the CD spectrum of UmuD′2 at the physiologically relevant concentration more closely resembles a random coil than the expected β-sheet (Fig. 1A). In an attempt to reconcile these results with the two previous high-resolution analyses of UmuD′2, which had revealed it to be a β-sheet-rich protein (13, 14), we took the CD spectrum of UmuD′2 at the high, nonphysiological protein concentration used to solve the NMR structure (14). Consistent with NMR and crystallography (13, 14), the CD spectrum of UmuD′2 at 2 mM displays more typical β-sheet character (Fig. 1A). Examination of full-length UmuD2 reveals the same striking anomaly, a CD spectrum resembling a random coil at 5 μM and one consistent with a β-sheet-rich protein at 2 mM (Fig. 1B).

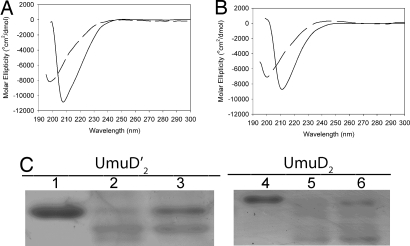

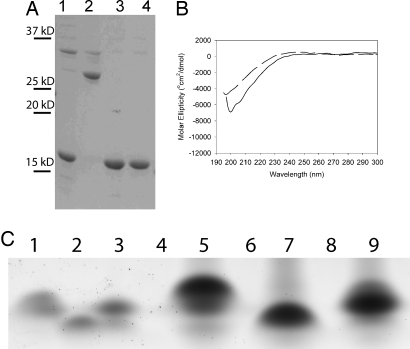

Fig. 1.

CD and limited proteolysis of umuD gene products. (A and B) CD spectra of 5 μM (dashed line) and 2 mM (solid line) UmuD′2 (A) or UmuD2 (B) at 25°C. (C) Limited proteolysis of 5 μM UmuD′2 (lanes 1–3) and 5 μM UmuD2 (lanes 4–6) at 37°C for 5 min. Lanes 1 and 4, 5 μM protein with no protease; lanes 2 and 5, proteins preequilibrated at 10 μM and diluted 1:1 with 5 mg/ml chymotrypsin; lanes 3 and 6, proteins freshly diluted to 10 μM 1 min before 1:1 dilution with 5 mg/ml chymotrypsin.

We then examined the effect of dilution on the susceptibility of UmuD′2 and UmuD2 to limited proteolysis by chymotrypsin over a 5-min time window. Consistent with the CD results, UmuD′2 or UmuD2 that has been preequilibrated at 10 μM results in more complete proteolysis than UmuD′2 or UmuD2 that has been freshly diluted from a 2 mM stock (Fig. 1C). The extent of degradation of freshly diluted UmuD′2 is ≈60% of that of preequilibrated UmuD′2, whereas freshly diluted UmuD2 is degraded at ≈85% the level of preequilibrated UmuD2.

The CD and proteolysis results at physiological concentrations are typical of IDPs, which lack significant α-helix and β-sheet structure in vitro (19–28). We therefore used PONDR protein disorder-prediction programs (30) to test the similarity of UmuD′2 and UmuD2 to known disordered sequences. We found that the extreme N terminus of UmuD′2 and much of the C-terminal regions of both UmuD′2 and UmuD2 are predicted to be disordered [supporting information (SI) Fig. 7]. Nevertheless, both proteins are active in vitro at physiologically relevant concentrations (SI Fig. 8).

Crowding Agents and Specific Protein–Protein Interactions Induce Secondary Structure in UmuD2 and UmuD′2.

To test whether the β-sheet-rich CD spectra of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 at mM concentrations result from specific self–self interactions or from more general crowding effects, we took the CD spectra of umuD gene products in the presence of the osmolytic crowding agent proline (31). Proline at 200 mM increases the secondary structure of both UmuD′2 (Fig. 2A) and UmuD2 (Fig. 2B). Less profound but consistent results are obtained with 2.5 M glucose (SI Fig. 9). Interestingly, other crowding agents such as PEG 8000, glycerol, and NaCl up to 1 M did not increase the secondary structure of UmuD2 or UmuD′2 (data not shown).

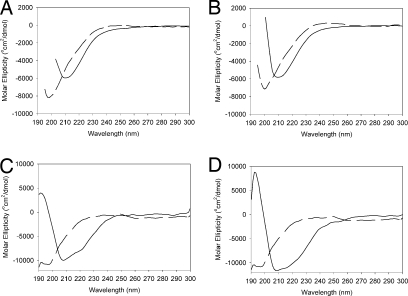

Fig. 2.

Induced secondary structure of umuD gene products. (A and B) CD spectra of UmuD′2 (A) or UmuD2 (B) in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 200 mM proline. (C) CD spectrum of UmuD2 alone (dashed line) or in the presence of DinB (solid line). (D) CD spectrum of UmuD2 alone (dashed line) or in the presence of the β-subunit of Pol III (solid line). The CD signal of DinB or β alone was subtracted from that of the complex to obtain the spectrum of bound UmuD2.

We have previously shown that UmuD2 interacts with DinB (KD = 0.64 μM) (7) and with the β-subunit of DNA Pol III (KD = 5.5 μM) (15). To test whether these interactions induce secondary structure in UmuD2 at μM concentrations, we took the CD spectrum of 50 μM UmuD2 in the presence of 50 μM interacting protein. After subtracting the signal from the interacting protein alone, the resulting spectra of UmuD2 in the presence of DinB (Fig. 2C) or of the β-subunit (Fig. 2D) reveal a nearly identical increase in β-sheet content. Because both the β-subunit and DinB have a more typical secondary structure than UmuD2 (data not shown), it is likely that the increase in secondary structure of the complex is mostly due to an increased β-sheet content in UmuD2. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that binding of UmuD2 may cause a conformational change in the interacting proteins as well (7, 15).

UmuD2 and UmuD′2 Are Dimeric at Physiologically Relevant Concentrations.

Although the data in Figs. 1 and 2 would be consistent with a coupled folding and dimerization model, several lines of evidence are inconsistent with monomeric umuD gene products at physiological concentrations. Gel filtration of UmuD′2 or UmuD2 shows that their elution volume is between the expected size of a dimer and that of a trimer (SI Fig. 10A) (5). Extensive evidence suggests dimeric forms of UmuD2, UmuD′2, and UmuD′D (5), whereas no evidence for trimers has been found. Both UmuD2 and UmuD′2 elute slightly earlier than expected for a globular dimer, representing a Stokes' radius that is ≈12% greater than expected for a 25- to 30-kDa globular protein. This increase is more indicative of a molten globule form of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 than a fully unfolded protein (28, 32). Guanidinium-denatured UmuD′ and UmuD behave as monomers, eluting earlier than their native counterparts and just before denatured chymotrypsin (14 kDa) (SI Fig. 10B). In 6 M guanidinium, UmuD and UmuD′ have Stokes' radii ≈75% greater than expected for globular monomers, between the radius expected for a premolten globule and a fully unfolded random coil (28, 32).

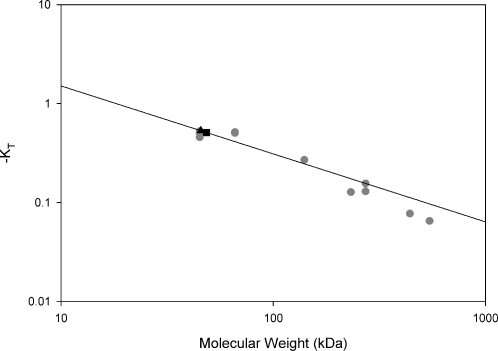

Native PAGE of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 at 500 nM (20 μl) and 5 μM (2 μl) shows that the proteins are dimeric at both uninduced and SOS-induced physiological concentrations (SI Fig. 10C). The major UmuD2 band runs nearly identically to a UmuD derivative, UmuD(F94C)2, that has been covalently cross-linked in the dimeric form (33). An equimolar mixture of UmuD and UmuD′ at these concentrations shows a predominant intermediate band corresponding to the UmuD′D heterodimer, rather than two distinct monomeric bands. The theoretical pI of all of these proteins is 4.5, making charge effects negligible. A Ferguson plot of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 compared with native PAGE standards shows that both UmuD2 and UmuD′2 migrate most similarly to the 45-kDa size standard (Fig. 3), which is consistent with gel filtration and inconsistent with a monomeric form of UmuD or UmuD′ at physiological concentrations.

Fig. 3.

Ferguson plot of native PAGE size standards (gray circles), UmuD′2 (filled square), and UmuD2 (filled triangle) was produced as described previously (51). The best fit of the plot of −KT versus molecular mass is to y = 7.3408x−0.6868. R = 0.958. Solving for the molecular mass of UmuD gives an estimate of 46 kDa and for UmuD′ an estimate of 49 kDa. The difference is not statistically significant. Native gel standards are 545 kDa jack bean urease hexamer, 440 kDa equine spleen ferritin, 272 kDa jack bean urease trimer, 232 kDa bovine liver catalase, 140 kDa bovine heart lactate dehydrogenase, 66 kDa BSA, and 45 kDa chicken egg white ovalbumin. Where more than one data point is present, multiple protein isoforms were analyzed.

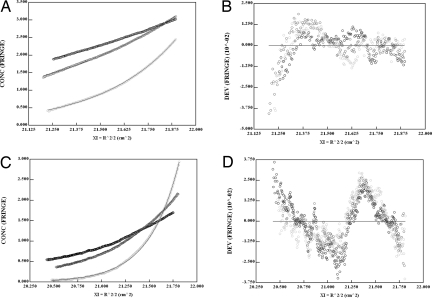

In an effort to determine the KD of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 homodimers, equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation was performed at three rotor speeds. The best fit of the data is to a single-species model (Fig. 4 A and C). The predicted molecular mass of UmuD′ at 20 μM is 25.4 kDa, compared with the monomer molecular mass of 12.5 kDa (Fig. 4A). The same model for UmuD at 40 μM (Fig. 4C) results in a fitted molecular mass of 31.0 kDa, in comparison with the predicted monomeric molecular mass of 15.1 kDa. If data are fit to a monomer–dimer equilibrium model, the KD generated is infinitely low. Residuals, although somewhat nonrandom (Fig. 4 B and D), are small and do not improve with fits to other theoretical models. The lower limit of KD determination for monomer–dimer equilibrium by using analytical ultracentrifugation is ≈10−11 M (34). Thus, despite the CD spectra at low concentrations, both UmuD2 and UmuD′2 are dimers with KDs of <10 pM, which is in the range of the KD of the related protein LexA (35).

Fig. 4.

Equilibrium analytical ultracentrifugation of UmuD′2 and UmuD2. (A and C) Results are shown for 20 μM UmuD′2 (A) and 40 μM UmuD2 (C). Data for three different speeds (16,000 rpm, filled circles; 20,000 rpm, dark gray circles; and 30,000 rpm, light gray circles) of Beckman Coulter rotor AN-50 Ti plotted with the best fit theoretical curve (single species of dimeric molecular mass) overlaid. (B) Residuals from data fitting to A. (D) Residuals from data fitting to C.

A Covalently Linked Variant of UmuD2 Has a CD Spectrum Resembling a Random Coil.

To confirm that the random coil CD signal of UmuD2 does not require a monomeric species, we analyzed the spectrum of disulfide cross-linked UmuD(F94C)2, which binds the β-subunit of DNA Pol III in a similar manner to wild type (33). Surprisingly, although this variant cross-links nearly quantitatively (Fig. 5A), it shows slightly less propensity for secondary structure than an otherwise equivalent mock-treated sample of UmuD(F94C) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Cross-linking does not constrain the secondary structure of UmuD2. (A) Extent of cross-linking of UmuD(F94C). Lane 1, mock-treated UmuD(F94C), no reductant; lane 2, cross-linked UmuD(F94C), no reductant; lane 3, mock-treated UmuD(F94C), with 1 mM DTT; lane 4, cross-linked UmuD(F94C), with 1 mM DTT. Positions of molecular mass markers are to the left of the gel. (B) CD spectra of cross-linked (dashed line) or mock-treated (solid line) UmuD(F94C). (C) Native gel electrophoresis of physiological and high concentrations of umuD gene products. Lanes 1–3, 5 μM; lanes 5–9, 2 mM; lanes 1 and 5, UmuD2; lanes 2 and 7, UmuD′2; lanes 3 and 9, UmuD′D.

We have no evidence of stable higher order oligomers of UmuD2 or UmuD′2 at 2 mM, wherein the CD spectrum shows considerable secondary structure, and UmuD′2 at this concentration has been shown to be dimeric (14). Native PAGE of 5 μM (20 μl) and 2 mM (0.5 μl) UmuD2, UmuD′2, and UmuD′D shows that all proteins have a consistent retention factor regardless of the starting concentration (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

These studies have led us to conclude that, at physiologically relevant concentrations, UmuD′2 and UmuD2 share structural characteristics with IDPs. Little is known about the precise structures of IDPs, although efforts to further characterize them have begun (28). In the case of UmuD2 and UmuD′2, a considerable amount of structural information is already available from solution studies at physiologically relevant concentrations (16–18, 29). Consistent with a flexible structure, cross-linking of single-cysteine derivatives of UmuD2 by slow, gentle methods such as dialysis shows that most derivatives will cross-link to form covalent UmuD2, with only a few positions that react much more or less than average (17). However, certain amino acid positions are consistently more solvent-exposed than others, and faster methods of cross-linking can better distinguish residues that are near the homodimer interface, suggesting that UmuD2 is likely to have a flexible but nonrandom structure in solution (16–18). The high-resolution structures of UmuD′2 (13, 14) both may have relevance to its structure in vivo, although inside the cell umuD gene products are likely to be surrounded by interaction partners that may influence their actual structure (Fig. 6A).

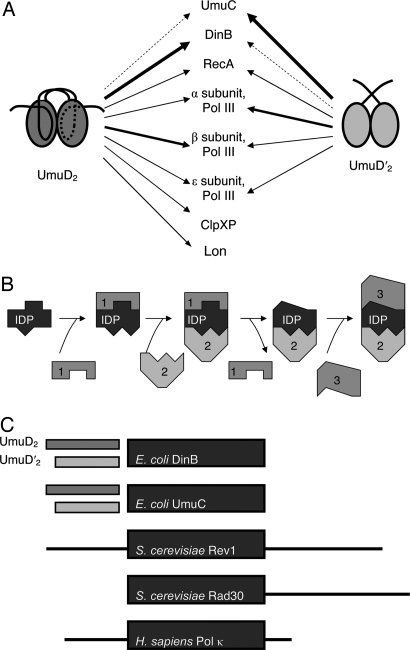

Fig. 6.

A model for sequential protein–protein interactions by IDPs. (A) UmuD2 and UmuD′2 make a variety of distinct protein–protein interactions. The relative binding affinities, if known, are represented by thick arrows (for strong interactions) or thin ones (for weak interactions). (B) Model for sequential protein–protein interactions with an IDP. An IDP may first bind to one interaction partner (1), which stabilizes a particular conformation. If a second binding interface becomes exposed in this conformation, another protein may now bind (2). The second binding event could destabilize the first protein–protein interaction, causing the original protein to exit the complex and possibly exposing a different interface. If so, a different partner (3) can bind at this site. (C) UmuD2 and UmuD′2 may act as interchangeable protein–protein interaction domains for E. coli Y family DNA polymerases. Y family DNA polymerases have conserved catalytic domains (large boxes), and many eukaryotic ones have extended interaction domains (lines on bottom three representations). Although these interaction domains are missing in the two E. coli Y family DNA polymerases, both of them interact with umuD gene products, which may serve as interchangeable protein–protein interaction domains in a streamlined bacterial genome.

UmuD2 and UmuD′2 share characteristics of hub proteins, which are represented in the interactomes of many organisms and make a large number of protein–protein contacts (36–38). Hub proteins have been found to have a larger degree of disorder than the general proteome (36–38), and those proteins that are relatively well ordered often have disordered binding partners (36). The high degree of disorder has been proposed as a mechanism to enable a large number of protein–protein interactions, especially transient interactions that are separated temporally or spatially (39). We suggest that the properties of IDPs might provide a simple mechanism for temporally ordering multiple protein interactions in hub proteins. An initial interaction may constrain the conformations of an IDP in such a manner as to expose a preferential binding interface for a second protein. After the second protein binds, the structure may change again to expose or occlude other binding interfaces (Fig. 6B). It is not known whether multiple interactions with umuD gene products occur simultaneously or in a stepwise fashion, although their role in timing regulation suggests that interactions may be transient.

The crystal structures of several DNA polymerase catalytic domains have been solved, but N-terminal or C-terminal protein–protein interaction domains are often removed to enable crystallization (40), possibly due to a tendency toward disorder in these regions. Although UmuC and DinB do not have these interaction domains, they both interact with disordered umuD gene products (5, 7). We suggest that, instead of being fused to a particular DNA polymerase, UmuD2 and UmuD′2 may act as interchangeable interaction domains for the two Y family DNA polymerases in Escherichia coli, thus allowing for a streamlined genome while maintaining the regulatory sensitivity of a disordered interaction module (Fig. 6C). A flexible structure that can adapt to multiple distinct protein–protein interactions helps explain how the small umuD gene products can make many specific interactions, and a posttranslational modification further differentiates these interactions (Fig. 6A).

Although IDPs are often involved in protein–protein contacts, few are known homodimers in solution. A stable quaternary structure in the absence of a rigid secondary structure is counterintuitive to the current protein-folding paradigm (41). However, limited examples are present in the literature, including the E. coli MazE antitoxin (42) and the human papillomavirus protein E7 (43). Both of these proteins have unfolded domains in addition to more rigid dimerization domains. Similarly, many of the residues in umuD gene products that are predicted to be ordered are at the dimer interface (SI Fig. 7).

Structural analysis of a dimeric protein can distinguish between a coupled folding-dimerization event and temporally separated folding and binding steps (44). Calculations for UmuD′2 based on its NMR structure (14) obtained by using the program MOLMOL (45) show that UmuD′2 has 75 Å of accessible surface area per residue and 22 Å of interface area per residue. These results suggest that the monomeric forms of UmuD and UmuD′, if they are ever present in solution, would be disordered and may undergo some disorder-to-order transition upon homodimerization (44). However, recent data show that a disorder-to-order transition is not necessary for homodimerization of one IDP, the T cell receptor ζ-subunit (46).

UmuD2 and UmuD′2 share homology with the dimerization domains of certain bacterial transcription factors (47). Transcription factors often have large regions of intrinsic disorder, either in their DNA-binding domains or in protein-interaction domains (48). The seemingly unrelated tendencies for transcription factors to be homodimeric and intrinsically disordered suggest that more homodimers with a large degree of structural plasticity may be found soon.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

RecA protein was purchased from New England Biolabs. High-molecular-weight native PAGE standards were obtained from GE Healthcare. Other protein standards and copper phenanthroline were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Native PAGE gels were obtained from Bio-Rad.

Protein Purification.

Purification of UmuD′2, UmuD2, and UmuD(F94C)2 (49) and cross-linking (50) were performed as previously described. A plasmidencoding UmuD(F94C) was produced from pSG5 by using the Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (49). Protein concentration was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay. DinB was a kind gift from Daniel Jarosz (49). ClpXP and the β subunit of Pol III were generously provided by the Baker Laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (11) and the Beuning Laboratory at Northeastern University (15), respectively.

CD Spectroscopy.

CD was performed on an Aviv Model 202 spectrometer. Spectra were recorded at 25°C; each data point represents the average of 3 s of data collection. Proteins at physiological concentrations were monitored by using a 350-μl 0.1-cm cuvette (Hellma), and proteins at ≥50 μM were recorded by using a 4-μl 0.01-cm cuvette (Wilmad). Spectra of umuD gene products alone were recorded in buffer consisting of 10 mM Na3PO4 (pH 6.8), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT. For interaction studies, the buffer was 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5% glycerol. The buffer spectrum was subtracted from that of the protein.

Limited Proteolysis.

UmuD′2 or UmuD2 was diluted to 10 μM in CD buffer and either incubated on ice for 2 h or used within 1 min. Proteolysis reactions were begun by adding 10 μl of 5 mg/ml chymotrypsin to 10 μl of UmuD′2 or UmuD2 and incubating at 37°C for 5 min. Reactions were stopped by addition of 4 μl of 6× SDS/PAGE-loading buffer [1× is 25 mM Tris·HCl (pH 6.8), 5% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 2% SDS, and 1 mM DTT] and freezing in liquid nitrogen. Proteins were run on 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Cambrex), stained with 1× SYPRO Orange (Molecular Probes) in 7.5% acetic acid, and quantified by using ImageQuant software.

Protein-Disorder Prediction.

Access to PONDR was provided by Molecular Kinetics. VL-XT is copyright 1999 by the Washington State University Research Foundation, all rights reserved. PONDR is copyright 2004 by Molecular Kinetics, all rights reserved.

Gel-Filtration Chromatography.

Gel filtration was performed by using a 100-ml Superdex 75 column on an Akta FPLC system (GE Healthcare). One milliliter of 5 μM protein solution was injected; UmuD2 and UmuD′2 were 5 μM at injection. The buffer described for CD spectroscopy was used as a running buffer. For denatured gel filtration, UmuD′2, UmuD2, and each size standard were denatured separately in CD buffer plus 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride for 2 h. Denatured samples were centrifuged for 1 min in a microcentrifuge at 16,000 × g to pellet aggregates prior to injection. CD buffer plus 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride was used for elution.

Native PAGE.

Proteins were diluted into 1× PAGE-loading buffer lacking SDS, incubated for 30 min at 25°C, and run at 20 V at 4°C overnight. Cross-linked UmuD(F94C)2 was diluted into 1× PAGE-loading buffer lacking both SDS and DTT. Gels were soaked in 0.05% SDS for 30 min and stained with 1× SYPRO Orange (Molecular Probes) in 7.5% acetic acid after running. Ferguson plots were calculated as described by using 5 μM UmuD2, UmuD′2, and UmuD′D (51).

Sedimentation Equilibrium.

Experiments were performed on a model XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge with an AN-50 Ti rotor at 20°C (Beckman Coulter). Proteins were dialyzed against three changes of 500-ml CD buffer at 4°C over 12 h. The reference solution was the final dialysis buffer. Protein gradients were monitored by interference. Each rotor speed was centrifuged for 12 h, and WinMatch software was used to confirm equilibrium. Rotor speeds were 16,000, 20,000, and 30,000 rpm; the same protein samples experienced all three rotor speeds. Only the last scan for each speed was used in the data analysis. Protein concentration was determined by direct analysis of each sample after the last scan. Data analysis was performed by using the software WinNonlin.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank members of the G.C.W., T. A. Baker, R. T. Sauer, A. E. Keating, J. A. King, P. J. Beuning, W. DeGrado, J. W. Little (especially Kim Giese), and G. A. Petsko/D. Ringe (especially Raquel Lieberman) laboratories for helpful discussions and use of equipment; Debbie Pheasant for help with instrumentation; Brent Cezairliyan for help in analytical ultracentrifugation analysis; and Karen Ohrenberger for help with manuscript preparation. This work was supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grant CA21615-27 (to G.C.W.), Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Environmental Health Sciences National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant P30 ES002109, Millennium Institute of Structural Biology in Biomedicine and Biotechnology Grant IMBEBB/CNPq (to R.M.-B.), the Biophysical Instrumentation Facility for the Study of Complex Macromolecular Systems, National Science Foundation Grant 0070319, and National Institutes of Health Grant GM68762. G.C.W. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor, and S.M.S. was a Cleo and Paul Schimmel Fellow.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0706067105/DC1.

References

- 1.Friedberg EC, et al. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. Washington, DC: Am Soc Microbiol; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opperman T, Murli S, Smith BT, Walker GC. A model for a umuDC-dependent prokaryotic DNA damage checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9218–9223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nohmi T, Battista JR, Dodson LA, Walker GC. RecA-mediated cleavage activates UmuD for mutagenesis: Mechanistic relationship between transcriptional derepression and posttranslational activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1816–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuven NB, Arad G, Maor-Shoshani A, Livneh Z. The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD′, RecA, and SSB, is specialized for translesion replication. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31763–31766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodgate R, Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Echols H. UmuC mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: Purification and interaction with UmuD and UmuD′. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7301–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang M, et al. UmuD′(2)C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8919–8924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarosz DF, et al. Substrate specificity and novel regulation of DinB activity in DNA damage tolerance. Mol Cell. 2007;28:1058–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutton MD, Opperman T, Walker GC. The Escherichia coli SOS mutagenesis proteins UmuD and UmuD′ interact physically with the replicative DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12373–12378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlacher K, Cox MM, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. RecA acts in trans to allow replication of damaged DNA by DNA polymerase V. Nature. 2006;442:883–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez M, Frank EG, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Lon-mediated proteolysis of the Escherichia coli UmuD mutagenesis protein: In vitro degradation and identification of residues required for proteolysis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3889–3899. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neher SB, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Distinct peptide signals in the UmuD and UmuD′ subunits of UmuD/D′ mediate tethering and substrate processing by the ClpXP protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13219–13224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235804100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank EG, Ennis DG, Gonzalez M, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Regulation of SOS mutagenesis by proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10291–10296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peat TS, et al. Structure of the UmuD′ protein and its regulation in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1996;380:727–730. doi: 10.1038/380727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferentz AE, Walker GC, Wagner G. Converting a DNA damage checkpoint effector (UmuD2C) into a lesion bypass polymerase (UmuD′2C). EMBO J. 2001;20:4287–4298. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beuning PJ, Simon SM, Zemla A, Barsky D, Walker GC. A non-cleavable UmuD variant that acts as a UmuD′ mimic. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9633–9640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MH, Ohta T, Walker GC. A monocysteine approach for probing the structure and interactions of the UmuD protein. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4825–4837. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4825-4837.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzzo A, Lee MH, Oda K, Walker GC. Analysis of the region between amino acids 30 and 42 of intact UmuD by a monocysteine approach. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7295–7303. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7295-7303.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MH, Walker GC. Interactions of Escherichia coli UmuD with activated RecA analyzed by cross-linking UmuD monocysteine derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7285–7294. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7285-7294.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Obradovic Z. Identification and functions of usefully disordered proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:25–49. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Showing your ID: Intrinsic disorder as an ID for recognition, regulation and cell signaling. J Mol Recognit. 2005;18:343–384. doi: 10.1002/jmr.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:321–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tompa P. The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3346–3354. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fink AL. Natively unfolded proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero P, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Natively disordered proteins: Functions and predictions. Appl Bioinformatics. 2004;3:105–113. doi: 10.2165/00822942-200403020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Receveur-Brechot V, Bourhis JM, Uversky VN, Canard B, Longhi S. Assessing protein disorder and induced folding. Proteins. 2006;62:24–45. doi: 10.1002/prot.20750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uversky VN. Natively unfolded proteins: A point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002;11:739–756. doi: 10.1110/ps.4210102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutton MD, et al. A model for the structure of the Escherichia coli SOS-regulated UmuD2 protein. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:77–93. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Gall T, Romero PR, Cortese MS, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in the protein data bank. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2007;24:325–342. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2007.10507123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Bolen DW. The peptide backbone plays a dominant role in protein stabilization by naturally occurring osmolytes. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12884–12891. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uversky VN. Use of fast protein size-exclusion liquid chromatography to study the unfolding of proteins which denature through the molten globule. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13288–13298. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutton MD, Narumi I, Walker GC. Posttranslational modification of the umuD-encoded subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V regulates its interactions with the beta processivity clamp. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5307–5312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082322099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tennyson RB, Lindsley JE. Type II DNA topoisomerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a stable dimer. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6107–6114. doi: 10.1021/bi970152f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohana-Borges R, et al. LexA repressor forms stable dimers in solution: The role of specific DNA in tightening protein–protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4708–4712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. Flexible nets: The roles of intrinsic disorder in protein interaction networks. Febs J. 2005;272:5129–5148. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dosztanyi Z, Chen J, Dunker AK, Simon I, Tompa P. Disorder and sequence repeats in hub proteins and their implications for network evolution. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2985–2995. doi: 10.1021/pr060171o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patil A, Nakamura H. Disordered domains and high surface charge confer hubs with the ability to interact with multiple proteins in interaction networks. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2041–2045. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh GP, Ganapathi M, Dash D. Role of intrinsic disorder in transient interactions of hub proteins. Proteins. 2006;66:761–765. doi: 10.1002/prot.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerlach VL, et al. Human and mouse homologs of Escherichia coli DinB (DNA polymerase IV), members of the UmuC/DinB superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11922–11927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sickmeier M, et al. DisProt: The database of disordered proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D786–D793. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lah J, et al. Energetics of structural transitions of the addiction antitoxin MazE: Is a programmed bacterial cell death dependent on the intrinsically flexible nature of the antitoxins? J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17397–17407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alonso LG, et al. High-risk (HPV16) human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein is highly stable and extended, with conformational transitions that could explain its multiple cellular binding partners. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10510–10518. doi: 10.1021/bi025579n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gunasekaran K, Nussinov R. How different are structurally flexible and rigid binding sites? Sequence and structural features discriminating proteins that do and do not undergo conformational change upon ligand binding. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:257–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sigalov AB, Zhuravleva AV, Orekhov VY. Binding of intrinsically disordered proteins is not necessarily accompanied by a structural transition to a folded form. Biochimie. 2007;89:419–421. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perry KL, Elledge SJ, Mitchell BB, Marsh L, Walker GC. umuDC and mucAB operons whose products are required for UV light- and chemical-induced mutagenesis: UmuD, MucA, and LexA proteins share homology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4331–4335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, et al. Intrinsic disorder in transcription factors. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6873–6888. doi: 10.1021/bi0602718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beuning PJ, Simon SM, Godoy VG, Jarosz DF, Walker GC. Characterization of Escherichia coli translesion synthesis polymerases and their accessory factors. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:318–340. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee MH, Guzzo A, Walker GC. Inhibition of RecA-mediated cleavage in covalent dimers of UmuD. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7304–7307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7304-7307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gallagher SR. Native discontinuous electrophoresis and generation of molecular weight standard curves (Ferguson plots). Current Protocols in Protein Sci. 1995:10.3.5–10.3.11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.