Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a common disorder of aging and a precursor lesion to full-blown multiple myeloma (MM). The mechanisms underlying the progression from MGUS to MM are incompletely understood but include the suppression of innate and adaptive antitumor immunity. Here, we demonstrate that NKG2D, an activating receptor on natural killer (NK) cells, CD8+ T lymphocytes, and MHC class I chain-related protein A (MICA), an NKG2D ligand induced in malignant plasma cells through DNA damage, contribute to the pathogenesis of MGUS and MM. MICA expression is increased on plasma cells from MGUS patients compared with normal donors, whereas MM patients display intermediate MICA levels and a high expression of ERp5, a protein disulfide isomerase linked to MICA shedding (sMICA). MM, but not MGUS, patients harbor circulating sMICA, which triggers the down-regulation of NKG2D and impaired lymphocyte cytotoxicity. In contrast, MGUS, but not MM, patients generate high-titer anti-MICA antibodies that antagonize the suppressive effects of sMICA and stimulate dendritic cell cross-presentation of malignant plasma cells. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor with anti-MM clinical efficacy, activates the DNA damage response to augment MICA expression in some MM cells, thereby enhancing their opsonization by anti-MICA antibodies. Together, these findings reveal that the alterations in the NKG2D pathway are associated with the progression from MGUS to MM and raise the possibility that anti-MICA monoclonal antibodies might prove therapeutic for these disorders.

Keywords: ERp5, MICA, NKG2D, plasma cell, tumor immunity

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is diagnosed in 3% of adults at least 50 years of age and is characterized by a restricted clonal expansion of antibody-secreting plasma cells in the bone marrow (1). MGUS evolves at a frequency of 1% per year to full-blown multiple myeloma (MM), a lethal malignancy in which dysregulated plasma cell homeostasis provokes bone marrow compromise, osteolytic lesions, metabolic perturbations, and kidney damage (2, 3). Expression profiling analyses reveal major differences between MGUS and normal plasma cells, but the distinctions between MGUS and MM are less pronounced (4). MGUS plasma cells display chromosomal alterations, including translocations that fuse sequences from the IgH locus to partner genes with oncogenic potential, whereas the progression to MM involves additional mutations in growth and survival pathways (5–7). An important role for XBP-1, which is a basic-region leucine zipper transcription factor required for plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response (8, 9), is underscored by the development of MGUS and MM in XBP-1-transgenic mice (10).

The pathogenesis of plasma cell malignancies reflects not only cell-intrinsic alterations but also the impact of host antitumor reactions. Dendritic cells and proinflammatory factors in the bone marrow may foster plasma cell accumulation (11, 12), whereas innate and adaptive lymphocytes may effectuate plasma cell death (13). Disease progression may be influenced, at least in part, by the balance of these competing host activities (14). In MGUS bone marrow, CD1d-restricted invariant natural killer (NK) T cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes manifest potent antitumor cytotoxicity (13, 15). At this stage of illness, T cells specific for SOX-2, a gene product involved in stem cell self-renewal, inhibit the clonogenicity of MM precursors and confer a reduced risk of evolution toward full-blown disease (16). In contrast, lymphocytes in MM bone marrow are functionally impaired (13, 15). Because ex vivo manipulations overcome these cellular defects (17), the tumor microenvironment is likely immunosuppressive, but the underlying mechanisms remain to be clarified.

Recent investigations have delineated a key role for the NKG2D pathway in immune-mediated tumor destruction (18). NKG2D is a C-type, lectin-like, type II transmembrane receptor expressed on NK cells, γδ T cells, and CD8+ T cells (19–21). Upon ligation, NKG2D signals through the adaptor protein DAP-10 to evoke perforin-dependent cytolysis and to provide costimulation. In humans, the NKG2D ligands include MHC class I chain-related protein A (MICA), the most extensively characterized member, the closely related MICB, UL-16-binding proteins 1–4, and RAE-1G (22, 23). MICA expression in normal tissues is restricted to the thymic epithelium and scattered cells in the gastrointestinal mucosa (24). However, MICA is commonly detected in solid and hematological malignancies (25–27), where it may be induced as part of the DNA damage response through ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related (ATR), and checkpoint kinases 1 and 2 (chk-1 and -2) (28).

In murine models, the enforced expression of NKG2D ligands on transplantable tumors elicits immune rejection by NK cells, CD8+ T lymphocytes, and perforin, whereas the administration of blocking antibodies to NKG2D enhances tumor susceptibility (29–33). Nonetheless, the constitutive expression of MICA on human tumors promotes ligand shedding, which triggers internalization of surface NKG2D, impaired NK cell and CD8+ T lymphocyte function, and expansion of an unusual population of NKG2D+CD4+ T cells with regulatory properties (34–37). The protein disulfide isomerase ERp5 contributes to MICA shedding (sMICA) through rendering the α3 domain susceptible to proteolysis at the cell surface (38), although a specific role for ERp5 during tumorigenesis has not been defined.

We recently reported that some advanced melanoma and non-small-cell lung carcinoma patients who responded to vaccination with irradiated, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-secreting tumor cells and antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) generated high-titer antibodies against MICA (39). These therapy-induced humoral reactions antagonized the immunosuppressive effects of sMICA and augmented innate and adaptive antitumor cytotoxicity. Here, we demonstrate that endogenous anti-MICA antibodies and ligand shedding are critical determinants of host immunity during the progression from MGUS to MM.

Results

MICA Expression in MGUS and MM.

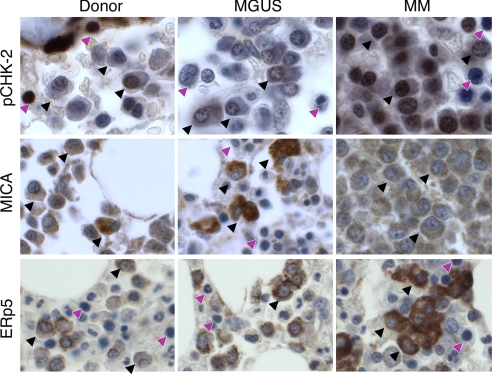

Activation of the DNA damage response is an early event during solid tumor carcinogenesis (40, 41) and may result in MICA up-regulation through an ATM, ATR, chk-1, and chk-2 signaling cascade (28). To determine whether this pathway is engaged during plasma cell transformation, we performed immunohistochemistry for phosphorylated chk-2 (thr 68) on bone marrow tissue microarrays prepared from healthy donors (n = 10) and untreated MGUS (n = 20) and MM (n = 40) patients. Although normal plasma cells showed minimal phospho-chk-2 staining, MGUS and, to a greater degree, MM plasma cells displayed strong reactivity that was primarily nuclear, suggesting that the DNA damage response is evoked early and then sustained during MM progression (Fig. 1Top). The chk-2 activation in MGUS plasma cells was associated with strong antibody staining for MICA, which was primarily surface and, to a lesser extent, cytoplasmic, in contrast to the absence of MICA expression in normal plasma cells (Fig. 1 Middle). Notwithstanding the intense immunoreactivity for phospho-chk-2, MM plasma cells manifested only moderate staining for MICA, which was primarily cytoplasmic. This unexpected expression profile raised the possibility that MM plasma cells might shed surface MICA. Indeed, MM plasma cells evidenced strong antibody staining for ERp5, a protein disulfide isomerase linked to MICA shedding (38), whereas MGUS and normal plasma cells were modestly reactive (Fig. 1 Bottom).

Fig. 1.

The DNA damage response is activated, and MICA and ERp5 expression are increased during MGUS/MM progression. Bone marrow tissue microarrays were prepared from healthy donors (n = 10) and patients with untreated MGUS (n = 20) or MM (n = 40) and were stained for phospho-chk-2 (Top), MICA (Middle), or ERp5 (Bottom). Representative examples from the arrays are shown. (×250 magnification.) Black arrows, plasma cells; purple arrows, nonplasma cells.

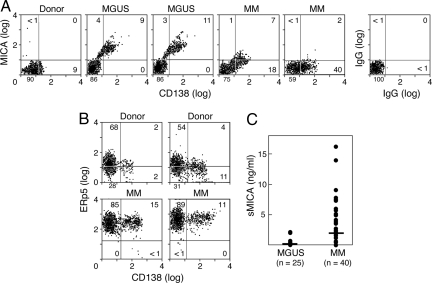

To characterize the cell surface expression of MICA and ERp5 in more detail, we performed flow cytometry on unfractionated bone marrow samples. Consistent with the immunohistochemistry data, CD138+ plasma cells from MGUS patients showed higher surface levels of MICA compared with MM patients, whereas plasma cells from normal donors failed to express MICA (Fig. 2A). Plasma cells and bone marrow mononuclear cells from MM patients also displayed much higher levels of ERp5 compared with normal donors (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the up-regulation of ERp5 was associated with MICA shedding (Fig. 2C) because MM patients frequently harbored circulating sMICA (median, 1.98 ng/ml; range, 0–16.2; n = 40), whereas nearly all MGUS patients (median, 0.10; range, 0–2.18; n = 25) and normal donors (data not shown) did not (MM vs. MGUS patients; P = 0.001). Together, these results indicate that the DNA damage response and ERp5 are important determinants of MICA induction and shedding during the progression of MM.

Fig. 2.

MICA and ERp5 plasma cell surface expression and MICA shedding during the progression of MM. (A) Bone marrow aspirates were stained for CD138 and MICA and analyzed with flow cytometry. The results are representative of three normal donors, three MGUS patients, and seven MM patients studied. (B) Bone marrow aspirates were stained for CD138 and ERp5. The results are representative of three normal donors and six MM patients studied. (C) Sera from MGUS and MM patients were evaluated for sMICA with an ELISA. The lower limits of the assay were 90 pg/ml.

sMICA Contributes to Immune Suppression in MM Patients.

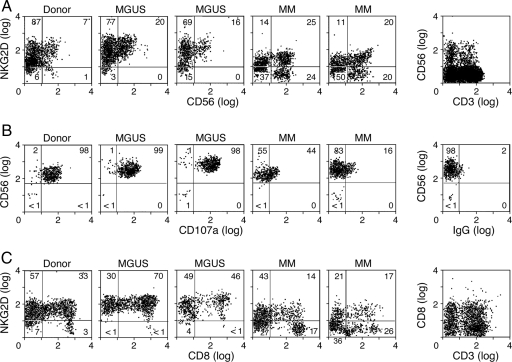

Because sMICA provokes NKG2D down-regulation and immune suppression (34), we characterized receptor expression as a function of disease progression. Peripheral blood CD56+ cells from MGUS patients displayed NKG2D levels that were equivalent to healthy donors, but MM patients with sMICA showed diminished NKG2D (Fig. 3A). To determine the functional consequence of this reduction, we quantified NK cell cytotoxicity toward K562 cells, which is primarily NKG2D-dependent [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6], by flow cytometry for CD107a, a lysosomal protein that traffics to the cell surface upon granule exocytosis (42). The lytic activity of NK cells from MGUS patients was comparable or increased compared with normal donors, whereas MM patients with sMICA manifested decreased CD107a mobilization (Fig. 3B). The importance of sMICA was underscored by the minimal impairment of cytotoxicity in NK cells from a patient with smoldering MM (SMM) (43) who did not harbor shed ligand and maintained intact NKG2D (SI Fig. 7). Peripheral blood CD8+ cells from MM patients with sMICA also evidenced diminished NKG2D, in contrast to the normal levels in MGUS subjects and the modest decrease in the SMM patient (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that sMICA contributes to the suppression of innate and adaptive immunity during the progression of MM.

Fig. 3.

NKG2D expression and cytotoxic lymphocyte function during the progression of MM. (A) PBMCs from normal donors and patients with MGUS or MM were evaluated for NKG2D expression on CD56+ cells by flow cytometry. The results are representative of three normal donors, three MGUS patients, and seven MM patients studied. (B) Magnetic bead-purified healthy donor, MGUS patient, or MM patient NK cells were tested for lytic activity against K562 targets by surface CD107a mobilization. The results are representative of three normal donors, three MGUS patients, and three MM patients studied. (C) PBMCs from normal donors and patients with MGUS or MM were evaluated for NKG2D expression on CD8+ cells by flow cytometry. The results are representative of three normal donors, three MGUS patients, and seven MM patients studied.

MGUS Patients Generate Anti-MICA Antibodies.

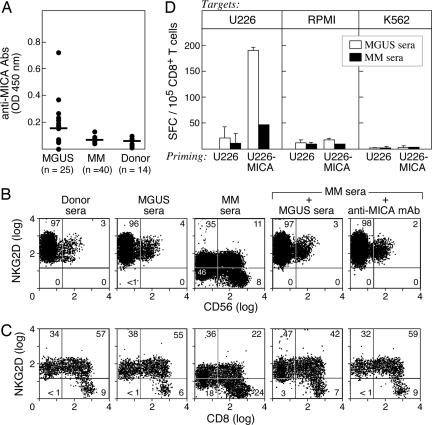

In contrast to the deleterious effects of sMICA, anti-MICA antibodies promote antitumor cytotoxicity (39, 44). To investigate whether these antibodies were generated during the pathogenesis of MM, we developed an ELISA with recombinant MICA protein and analyzed sera samples (Fig. 4A). MGUS patients (n = 25) frequently developed anti-MICA antibodies (median absorbance at 1:100 sera dilution, 0.156; range, 0.054–0.715), but MM patients (n = 40) displayed only weak reactivity (median 0.067, range 0.038–0.13), which was minimally increased above normal donors (n = 14) (median 0.049, range 0.024–0.092). The differences between the MGUS and MM patients were highly significant (P = 0.0002).

Fig. 4.

MGUS patients develop anti-MICA antibodies with functional activity. (A) Sera from MGUS or MM patients and healthy donors were diluted 1:100 and analyzed by ELISA with recombinant MICA protein. The reactivity was determined with a pan-IgG secondary. (B) Donor PBMCs were incubated for 48 h in the indicated sera, and then the NKG2D expression on CD56+ cells was determined with flow cytometry. Anti-MICA monoclonal antibodies were added where indicated. (C) CD8+ cells are shown. Similar results were observed by using three different MGUS and MM sera samples. (D) Dendritic cells were generated from adherent donor PBMCs, loaded with MGUS or MM sera-coated U226 or U226-MICA MM cells, matured with LPS, and used to stimulate autologous-purified CD8+ T cells for 7 days. IFN-γ production was measured by ELISPOT against K562 cells or dendritic cells loaded with U226 or RPMI-8226 MM cells. No reactivity against unpulsed dendritic cells or dendritic cells loaded with unopsonized tumors was observed (data not shown).

To characterize the biological properties of the anti-MICA antibodies, we tested their ability to antagonize the down-regulation of NKG2D evoked by sMICA. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors were incubated in various sera for 48 h. MM, but not MGUS or donor, sera resulted in diminished NKG2D levels on CD56+ cells (Fig. 4B) and impaired killing of K562 targets (SI Fig. 6). However, the admixing of MGUS and MM sera (1:1 ratio) blocked the decrease in NKG2D expression at comparable efficiency to the addition of anti-MICA monoclonal antibodies. MGUS sera similarly prevented the reduction in NKG2D on donor CD8+ peripheral blood cells exposed to MM sera (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that the anti-MICA antibodies generated in MGUS are neutralizing, and that sMICA, but not other factors such as TGF-β (45), underlies the decreased NKG2D levels in MM.

To determine whether the anti-MICA antibodies also recognize the cell surface ligand, we evaluated the cross-presentation of U226 MM cells (46). Although this line did not express MICA at baseline, γ-irradiation augmented expression (data not shown). To optimize the analysis, however, we used retroviral-mediated gene transfer to engineer U226 cells with stable, high-level MICA expression (U226-MICA). Dendritic cells were generated from a healthy donor by culture of peripheral blood monocytes in GM-CSF and IL-4. The expanded dendritic cells were pulsed with sera-coated tumor cells, matured with LPS, and used to simulate purified donor CD8+ T cells for 7 days. MM-specific IFN-γ production was assessed by ELISPOT. MGUS sera mediated efficient MICA-dependent cross-presentation of U226 cells, resulting in tumor-specific CD8+ T cells but little reactivity to RPMI MM cells or K562 targets (Fig. 4D). In contrast, MM sera were minimally active. These findings indicate that anti-MICA antibodies in MGUS sera effectively opsonize malignant plasma cells, which might contribute to the induction and/or maintenance of potent antitumor cytotoxic CD8+ T cells during the early stages of MM.

Bortezomib Increases MICA Expression in Some MM Cells.

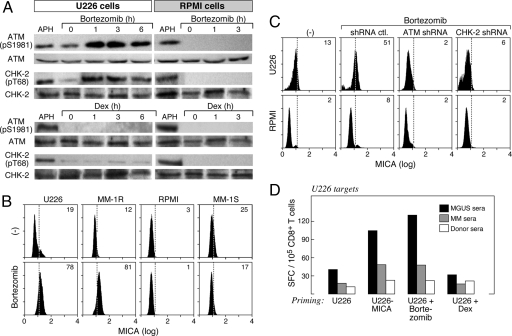

In light of the important roles of MICA and NKG2D in MM pathogenesis, we wondered whether anti-MM therapies might impact their function. The proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib achieves potent anti-MM clinical efficacy through targeting the NF-κB pathway, the unfolded protein response, and MAP kinases (47). However, because the DNA damage response is regulated, at least in part, through ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (48), Bortezomib also might modulate this pathway. Indeed, Bortezomib triggered the rapid phosphorylation of ATM (ser 1981) and chk-2 (thr 68) in U226 MM, but not RPMI MM, cells, whereas dexamethasone, another agent with anti-MM clinical efficacy, failed to activate the pathway in either line (Fig. 5A). Moreover, Bortezomib stimulated the degradation of ATM in MM-1S MM cells (SI Fig. 8), revealing a diversity of effects on the DNA damage response.

Fig. 5.

Bortezomib activates the DNA damage response and increases MICA expression in some MM cells. (A) U226 and RPMI-8226 MM cells were treated with 20 μM Bortezomib, 250 μg/ml dexamethasone, or 10 μg/ml aphidicolin (a DNA polymerase inhibitor that serves as a control for inducing DNA damage) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were prepared and evaluated for phospho-ATM (ser 1981), ATM, phospho-chk-2 (thr 68), or chk-2 by immunoblotting. (B) The indicated MM cells were treated with 20 μM Bortezomib overnight, and surface MICA expression was determined with flow cytometry. (C) U226 and RPMI-8226 MM cells were transfected with plasmids encoding control, ATM, or chk-2 shRNAs; exposed to Bortezomib overnight; and assayed for MICA expression with flow cytometry. (D) Dendritic cells were generated from adherent donor PBMCs; loaded with MGUS, MM, or normal sera-coated U226, U226-MICA, Bortezomib-treated U226, or dexamethasone-treated U226 MM cells; matured with LPS; and used to stimulate autologous-purified CD8+ T cells for 7 days. IFN-γ production was measured by ELISPOT against dendritic cells loaded with U226 MM cells. No reactivity against K562 cells, unpulsed dendritic cells, or dendritic cells loaded with unopsonized tumors was observed (data not shown). Results are representative of four donors. Points were performed in triplicate. Means are shown, with SD < 10%.

Consistent with the phosphorylation of ATM and chk-2 in U226 MM and MM-1R MM cells (data not shown), Bortezomib increased the surface expression of MICA in these lines, but not in RPMI or MM-1S cells (Fig. 5B). In contrast, dexamethasone did not alter MICA levels in any of the lines tested (data not shown). The Bortezomib-mediated up-regulation of MICA in U226 MM cells required the DNA damage response because shRNA silencing of ATM or chk-2 blocked ligand induction (Fig. 5C). Bortezomib also enhanced the immunogenicity of U226 MM cells because MGUS sera effectuated the dendritic cell cross-presentation of Bortezomib-treated cells as efficiently as U226-MICA cells, thereby engendering potent anti-MM CD8+ T cell responses (Fig. 5D). shRNA silencing of ATM or chk-2 abrogated the immunostimulatory effects of Bortezomib in U226 cells (data not shown), whereas the cross-presentation of dexamethasone-treated cells by MGUS sera was equivalent to untreated U226 cells, highlighting the specificity for MICA. These findings raise the possibility that anti-MICA monoclonal antibodies might potentiate the clinical activity of Bortezomib in some patients.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of MM involves the interplay of cell-autonomous perturbations in the growth and survival with host pro- and antitumorigenic reactions. Here we demonstrate that MICA functions as a link between cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic modes of MM suppression. During MGUS, the earliest detectable phase of plasma cell transformation, the DNA damage response is activated, whereupon cellular repair networks and surface MICA expression are coordinately induced. NKG2D-dependent recognition of malignant plasma cells stimulates innate and adaptive lymphocytes to mediate antitumor cytotoxicity, whereas anti-MICA antibodies antagonize nascent-soluble ligand and augment dendritic cell cross-presentation of tumor antigens. Nonetheless, during full-blown MM, the up-regulation of ERp5 promotes efficient MICA shedding, which evokes NKG2D internalization and immune suppression. Thus, stage-specific alterations in MICA activity are associated with the conversion of immune equilibrium to immune escape.

MGUS plasma cells harbor chromosomal alterations, including translocations that partner the IgH locus to various genes with transforming potential (5–7). These translocations likely arise during class switching and/or somatic hypermutation from aberrant repair of dsDNA breaks introduced by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) (49). In murine germinal center B cells, AID triggers NKG2D ligand expression through chk-1 phosphorylation (50). The persistent chk-2 phosphorylation that we observed throughout MM progression implies that malignant plasma cells experience tonic DNA damage, which may fuel the acquisition of additional pathogenic events. Among these events, increased ERp5 surface levels are critical to the loss of immune control, and characterization of the oncogenic pathways that regulate this protein disulfide isomerase is an important goal for future studies.

The biological properties of the anti-MICA antibodies generated in MGUS patients resemble those elicited in solid tumor patients by treatment with CTLA-4 blockade and vaccination with irradiated, GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells (39). These similarities in function raise the idea that particular antibodies might be selected for immunoregulatory capability. Surprisingly, the anti-MICA antibodies present in MGUS sera fail to inhibit NKG2D-dependent NK cell lysis of K562 targets (SI Fig. 6). Although this lysis might reflect the multiplicity of NKG2D ligands on K562 cells (data not shown), an intriguing possibility is that the humoral reactions do not block receptor activation despite their ability to neutralize sMICA. Identification of the epitopes targeted for immune recognition should illuminate this issue. MGUS patients manifest lower titers of anti-MICA antibodies than subjects responding to immunotherapy, which might contribute to the accumulation of sMICA upon MM progression. The basis for the loss of anti-MICA antibodies during full-blown MM requires further investigation.

Our results are consistent with a recent report that delineated high levels of sMICA as an adverse prognostic factor in patients with newly diagnosed MM (51). Together, these findings suggest that the infusion of anti-MICA monoclonal antibodies might help restore immune equilibrium and effectuate immune control. Indeed, Bortezomib stimulated MICA surface expression in some MM cells, thereby enhancing their sensitivity to antibody-mediated dendritic cell cross-presentation. Whereas the mechanisms through which proteasome inhibition modulates the DNA damage response remain to be clarified, our studies indicate that Bortezomib might be effectively integrated with anti-MICA antibodies as a combination therapy for plasma cell malignancies.

Methods

Clinical Samples and MM Lines.

Sera, lymphocytes, and tumor samples were obtained from patients enrolled in Institutional Review Board-approved Dana–Farber/Partners Cancer Care clinical protocols. U226, RPMI, and MM-1R cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, and the MM-1S cells were a gift of Steven Rosen (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL). MM lines were cultured in complete media (RPMI medium 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FCS, penicillin, and streptomycin) and in some experiments were treated with 5–20 nM Bortezomib (Millennium Pharmaceuticals), 10 μg/ml aphidicolin (Sigma–Aldrich), or 250 μg/ml dexamethasone for up to 16 h. U226-MICA cells were generated with retroviral-mediated gene transfer as described previously (39).

Pathology.

Zenker-fixed, decalcified bone marrow tissue microarrays were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5-μm thickness. The microarrays were treated for antigen retrieval with a pressure cooker for 20 min and then incubated with 5 μg/ml primary antibodies or a corresponding IgG fraction of preimmune serum in 3% BSA/PBS blocking solution for 16 h at 4°C. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were rabbit anti-phospho-chk-2 (thr 68) Ab (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-ERp5 Ab (Axxora Platform), and mouse anti-MICA Ab (PharMingen). The primary antibodies were then visualized with the corresponding secondary biotinylated antibody and the streptavidin-peroxidase complex from Vector Laboratories.

Flow Cytometry.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and bone marrow aspirates were processed by Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham Pharmacia) density-gradient centrifugation. In some experiments, donor cells were incubated in patient or control sera (10%) in complete media for 48 h before staining. The antibodies used were PE-conjugated anti-NKG2D mAb, FITC-conjugated anti-CD138, FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 mAb (PharMingen), PC5-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb, PC5-conjugated anti-CD56 mAb (Beckman-Coulter), PE-conjugated anti-MICA mAb (R&D Systems), and anti-ERp5 (Axxora Platform) followed by FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit (Southern Biotech). Cells were analyzed with a FW501 flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter).

Serology and Immunoblotting.

Anti-MICA antibodies and sMICA levels were measured with ELISAs by using recombinant MICA protein (ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene) and anti-human MICA monoclonal antibodies (R&D Systems) as described previously (39). The Wilcoxon rank sum test with no adjustments for multiple comparisons was used to analyze the differences among the normal donors, MGUS patients, and MM patients.

Antibodies used for immunoblotting were anti-phospho-ATM (ser 1981), anti-ATM, anti-phospho-ATR (ser 428), anti-ATR, anti-phospho-chk-1 (ser 280), and anti-phospho-chk-2 (thr 68) (Cell Signaling Technology). In some experiments, U226 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids encoding human chk-1 shRNA (5′-CAACTTGCTGTGAATAGAAT-3′), chk-2 shRNA, or ATM shRNA (Upstate Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The efficiency of gene knockdown was 50–90% as assessed by immunoblotting.

Cellular Assays.

NK or CD8+ T cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions, yielding populations that were 90% pure. NK cells were cultured with K562 cells at a 5:1 ratio for 4 h and stained with FITC-conjugated CD107a mAb (BD PharMingen). In some experiments, NK cells purified from donor PBMCs that were incubated in 10% patient sera were tested in 4-h lysis assays against 51Cr-labeled K562 target cells as described previously (39). The spontaneous release in all assays was <20% of the maximum.

Dendritic cells (generated from adherent PBMCs with GM-CSF and IL-4) were cocultured with opsonized tumor cells (1:1 ratio) for 20 h, matured with LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h, and then used to stimulate autologous CD8+ T cells, isolated by magnetic cell sorting, for 7 days. Antigen-specific IFN-γ production was then determined by ELISPOT as described previously (39).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

This work was supported by the Uehara Memorial Foundation; the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Sciences (M.J.); National Institutes of Health Grants CA78378, CA111506, and AI29530; and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (G.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0711293105/DC1.

References

- 1.Kyle RA, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1362–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RA, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:564–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa01133202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: A report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies FE, et al. Insights into the multistep transformation of MGUS to myeloma using microarray expression analysis. Blood. 2003;102:4504–4511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL. Multiple myeloma: Evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:175–187. doi: 10.1038/nrc746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM. Molecular pathogenesis and a consequent classification of multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6333–6338. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrasco DR, et al. High-resolution genomic profiles define distinct clinico-pathogenetic subgroups of multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reimold AM, et al. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwakoshi NN, et al. Plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response intersect at the transcription factor XBP-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:321–329. doi: 10.1038/ni907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrasco DR, et al. The differentiation and stress response factor XBP-1 drives multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kukreja A, et al. Enhancement of clonogenicity of human multiple myeloma by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1859–1865. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prabhala RH, et al. Dysfunctional T regulatory cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:301–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Osman K, Geller MD. Vigorous premalignancy-specific effector T cell response in the bone marrow of patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1753–1757. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dranoff G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhodapkar MV, et al. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1667–1676. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spisek R, et al. Frequent and specific immunity to the embryonal stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2007;204:831–840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Olson K. T cells from the tumor microenvironment of patients with progressive myeloma can generate strong, tumor-specific cytolytic responses to autologous, tumor-loaded dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13009–13013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202491499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diefenbach A, Raulet D. The innate immune response to tumors and its role in the induction of T-cell immunity. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:9–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groh V, Steinle A, Bauer S, Spies T. Recognition of stress-induced MHC molecules by intestinal epithelial gammadelta T cells. Science. 1998;279:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer S, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu J, et al. An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10. Science. 1999;285:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogasawara K, Lanier LL. NKG2D in NK, T cell-mediated immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2005;25:534–540. doi: 10.1007/s10875-005-8786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez S, Groh V, Spies T. Immunobiology of human NKG2D and its ligands. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;298:121–138. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groh V, et al. Cell stress-regulated human major histocompatibility complex class I gene expressed in gastrointestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12445–12450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groh V, et al. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gd T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6879–6884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girlanda S, et al. MICA expressed by multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance plasma cells costimulates pamidronate-activated gammadelta lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7502–7508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carbone E, et al. HLA class I, NKG2D, and natural cytotoxicity receptors regulate multiple myeloma cell recognition by natural killer cells. Blood. 2005;105:251–258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436:1186–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature03884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamieson AM, et al. The role of the NKG2D immunoreceptor in immune cell activation and natural killing. Immunity. 2002;17:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diefenbach A, et al. Ligands for the murine NKG2D receptor: Expression by tumor cells and activation of NK cells and macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:119–126. doi: 10.1038/77793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diefenbach A, Jensen ER, Jamieson AM, Raulet DH. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature. 2001;413:165–171. doi: 10.1038/35093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerwenka A, Baron JL, Lanier LL. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible-1 gene (RAE-1) permits natural killer cell-mediated rejection of a MHC class I-bearing tumor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11521–11526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201238598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smyth MJ, et al. NKG2D function protects the host from tumor initiation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:583–588. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groh V, Wu J, Yee C, Spies T. Tumour-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 2002;419:734–738. doi: 10.1038/nature01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salih HR, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Cutting edge: Down-regulation of MICA on human tumors by proteolytic shedding. J Immunol. 2002;169:4098–4102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groh V, Smythe K, Dai Z, Spies T. Fas-ligand-mediated paracrine T cell regulation by the receptor NKG2D in tumor immunity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:755–762. doi: 10.1038/ni1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu JD, et al. Prevalent expression of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related molecule is counteracted by shedding in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:560–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI22206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiser BK, et al. Disulphide-isomerase-enabled shedding of tumour-associated NKG2D ligands. Nature. 2007;447:482–486. doi: 10.1038/nature05768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jinushi M, Hodi FS, Dranoff G. Therapy-induced antibodies to MHC class I chain-related protein A antagonize immune suppression and stimulate antitumor cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9190–9195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603503103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartkova J, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorgoulis VG, et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alter G, Malenfant JM, Altfeld M. CD107a as a functional marker for the identification of natural killer cell activity. J Immunol Methods. 2004;294:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyle RA, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Groh V, et al. Efficient cross-priming of tumor antigen-specific T cells by dendritic cells sensitized with diverse anti-MICA opsonized tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6461–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501953102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castriconi R, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 inhibits expression of NKp30 and NKG2D receptors: Consequences for the NK-mediated killing of dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4120–4125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730640100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dhodapkar KM, Krasovsky J, Williamson B, Dhodapkar MV. Antitumor monoclonal antibodies enhance cross-presentation of cellular antigens and the generation of myeloma-specific killer T cells by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:125–133. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson PG, Mitsiades C, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Bortezomib: Proteasome inhibition as an effective anticancer therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:33–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.042905.122625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang YW, et al. Genotoxic stress targets human Chk1 for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol Cell. 2005;19:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okazaki IM, Kotani A, Honjo T. Role of AID in tumorigenesis. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:245–273. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gourzi P, Leonova T, Papavasiliou FN. A role for activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the host response against a transforming retrovirus. Immunity. 2006;24:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rebmann V, et al. Soluble MICA as an independent prognostic factor for the overall survival and progression-free survival of multiple myeloma patients. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.