Abstract

Movement in Caenorhabditis elegans is the result of sensory cues creating stimulatory and inhibitory output from sensory neurons. Four interneurons (AIA, AIB, AIY, and AIZ) are the primary recipients of this information that is further processed en route to motor neurons and muscle contraction. C. elegans has >1,000 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and their contribution to sensory-based movement is largely undefined. We show that an allatostatin/galanin-like GPCR (NPR-9) is found exclusively in the paired AIB interneuron. AIB interneurons are associated with local search/pivoting behavior. npr-9 mutants display an increased local search/pivoting that impairs their ability to roam and travel long distances on food. With impaired roaming behavior on food npr-9 mutants accumulate more intestinal fat as compared with wild type. Overexpression of NPR-9 resulted in a gain-of-function phenotype that exhibits enhanced forward movement with lost pivoting behavior off food. As such the animal travels a great distance off food, creating arcs to return to food. These findings indicate that NPR-9 has inhibitory effects on the AIB interneuron to regulate foraging behavior, which, in turn, may affect metabolic rate and lipid storage.

Keywords: neuropeptide receptor, nerve transmission, foraging, glutamate receptor, interneuron

A major challenge in neurobiology is to understand the control of behavior at the molecular level. Neuropeptides and their receptors offer promising candidates for the regulation of various behaviors and changes in physiology. The Caenorhabditis elegans genome sequence has allowed the identification of 109 putative neuropeptide genes encoding precursors that may be processed to ≈250 neuropeptides (1–3). These neuropeptides are grouped into three families: FMRFamide-related peptides (flp), insulin-like peptides (ins), and neuropeptide-like-peptides (nlps). C. elegans expresses >1,000 orphan G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). More than 50 GPCRs resemble known receptors for known neuropeptide families based on phylogenetic comparisons with known vertebrate GPCRs (4). Of these GPCRs, based on sequence identity, C. elegans gene ZK455.3 expresses an nlp receptor, NPR-9, that is most similar to insect allatostatin/mammalian galanin receptors (5–8). Allatostatins are a family of neuropeptides that share a conserved C-terminal sequence -Tyr/PheXaaPheGlyLeu-NH2 and are widespread throughout the invertebrate lineage (9, 10). In insects, allatostatins regulate numerous physiological functions, including inhibition of juvenile hormone biosynthesis (11, 12), inhibition of muscle contraction (13), myoendocrine regulation (14, 15), neuromodulation (16), and regulation of enzymatic activities (17) and ecdysis (18). Similarly, mammalian galanin modulates a wide variety of processes that range from neurotransmission, nociception, feeding and metabolism, energy and osmotic homeostasis and learning and memory (19). We report that NPR-9 is uniquely localized in interneuron AIB to negatively regulate a variety of inputs that affect locomotory activity on food that, in turn, affects lipid accumulation.

Results

NPR-9 Is Expressed Exclusively in the AIB Interneuron.

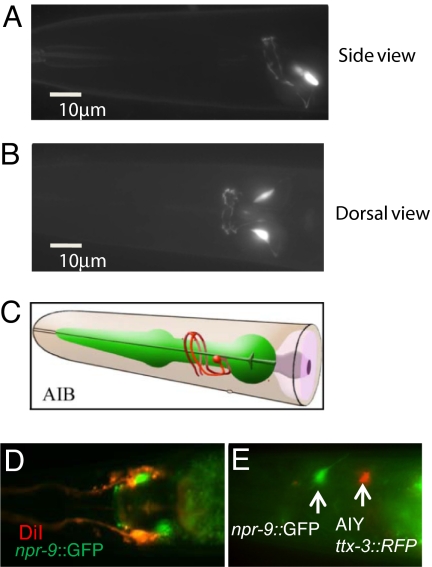

To determine the npr-9 expression pattern, transgenic worms were created that expressed 2 kb of the npr-9 promoter fused to GFP. GFP fluorescence was observed in paired neurons situated in the head region around the posterior pharyngeal bulb. The unique morphology suggested that expression was in the AIB interneuron pair (Fig. 1 A and B). Fig. 1C is a cartoon depicting the morphology of AIB (Wormbase, www.wormbase.org). We ruled out that this neuron is not an amphid neuron based on lack of overlap with DiI fluorescence. DiI is a fluorescent dye that stains five amphid neuron pairs (ADL, ASK, ASI, ASH, and ASJ). DiI also stains AWB amphid wing cells that show similar cell body and neuronal processes in close proximity to amphid neurons (Fig. 1D). An AIY reporter (otIs133) was used to show that npr-9:: GFP expression was not colocalized to the AIY interneuron (Fig. 1E). Based on cell position, DiI staining, costaining, and morphology we concluded that npr-9 is expressed in the AIB interneuron. No GFP fluorescence was noted in somatic gonad tissue, vulval muscle, body wall, and inner labial neurons. An identical pattern of head neuron GFP expression was noted during all larval stages (L1, L2, L3, and L4) and in hermaphrodite adults. There was no GFP expression detected in embryos.

Fig. 1.

NPR-9 is expressed in the AIB interneuron. Z stack projections of npr-9::GFP expression. (A) Side view. (B) Dorsal view. (C) A cartoon diagram is shown. AIB cartoon is from WormAtlas, www.wormatlas.org. (D) npr-9::GFP does not colocalize with amphid neurons. DiI (red) shows amphid neurons nlp-9::GFP (green) expression. (E) npr-9::GFP (green) does not colocalize with an AIY marker (red). (Magnification: D and E, ×630.)

Mutant npr-9 Worms Mimic the On-Food Foraging Defect of the “Lurcher” Worm.

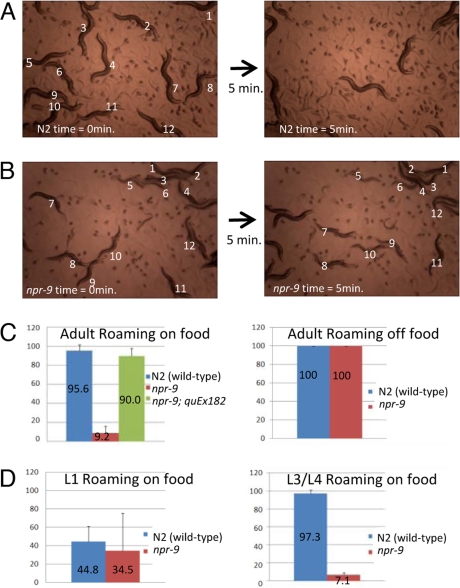

C. elegans displays simple locomotory foraging behavioral states of either roaming or dwelling. On food, wild-type worms roam in a high-speed forward direction that is interrupted by brief backward movement to usually change the direction of forward movement. Food sensory input eventually results in the worm's dwelling, which is defined by low speed/high turning (20). We examined a mutant npr-9 that was derived from a 318-bp deletion allele npr-9(tm1652) that is predicted to encode a null (out-of-frame truncation after the first four transmembrane domains). Time-lapsed microscopy was used to record C. elegans behavior on or off food and at various stages of development. npr-9 mutants displayed a lack of roaming behavior on food [Fig. 2 A and B and supporting information (SI) Movies 1 and 2]. After 5 min of recording the majority of npr-9 mutants had not moved more than a few body lengths from their original position (Fig. 2 B and C). The npr-9 mutants have a phenotype that is reminiscent of a transgenic worm expressing a dominant form of the glutamate receptor (Lurcher mouse/worm mutation) (21). The loss of the roaming behavior was not observed in L1 animals even though npr-9::GFP expression was detected at this stage (Fig. 2D). Sensory input, such as the availability of food, has a dramatic effect on egg laying rate (22). NPR-9 appears not to be related to reproduction as no difference in egg laying rate, embryonic lethality, or brood size was noted between wild type and npr-9 mutant. Dauer formation and L1 arrest were also similar to wild type in the npr-9 mutant (data not shown). When the animals are not on food, the npr-9 mutant animals display shortened forward movement and high angle turns equivalent to (N2) wild-type animals (23, 24) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

nrp-9(tm1652) animals display abnormal foraging behavior. (A) N2 (wild type) animals show a roaming behavior. Twelve animals are numbered at time 0 (Left), and 5 min later their positions are indicated (Right). All 12 N2 worms tracked exited the field of view. Worms not numbered are new worms that crawled onto the field or were not tracked. (B) npr-9(tm1652) mutants show a loss of roaming. Twelve npr-9 animals tracked as in A are still in the camera view even after 5 min. (Magnification: A and B, ×40.) (C) Quantification of the foraging behavior. Percentage of adult animals that display a roaming foraging behavior on food (Left) or off food (Right) is shown. An extrachromosomal array carrying the npr-9 gene (quEx182) rescued the npr-9(tm1652) mutant phenotype. (D) npr-9(tm1652) first instar (L1) larvae do not display abnormal roaming behavior. (Left) L1 npr-9(tm1652) animals roaming is not significantly different from wild-type L1 animals. (Right) In the third and fourth instar (L3/L4) stage the npr-9(tm1652) roaming behavior is lost. Error bars equal SEM.

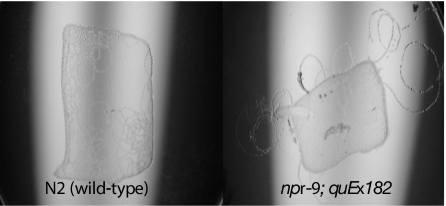

Rescue of npr-9 Mutants Resulted in Gain-of-Function Roamers.

Transgenic worms (npr9;quEx182) were created where NPR-9 was expressed in the npr-9 mutant background. Rescued animals regained roaming activity on food (Fig. 2C). Normally, wild-type worms rarely move off food but when they leave food they exhibit shortened forward movement, increased frequency of long reversals, and increased frequency of high angle omega turns in a behavior geared to rapidly return to food (25). Transgenic rescued npr-9 mutant worms had a tendency to roam off the food and in some cases traveled large distances in a forward direction but created turns that made an arced travel path back to the food (Fig. 3 and SI Movies 3–5).

Fig. 3.

Overexpressing npr-9 causes a hyperroaming “gain-of-function” phenotype. Wild-type (Left) and npr-9 overexpressing (Right) animals were placed on an E. coli OP50 lawn (food), and their tracks were photographed 18 h later. N2 wild-type animals rarely leave the E. coli lawn. In contrast, npr-9 overexpressing animals roam off the E. coli lawn and make large circles as evident by their tracks. (Magnification: life size.)

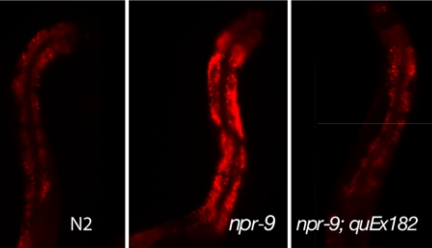

Mutant npr-9 Worms Accumulate Intestinal Lipid.

As mutant npr-9 worms spend more localized time on food and limit their movement, we analyzed whether the mutant would accumulate more fat relative to wild type. Nile red staining confirmed that npr-9 mutant worms are in fact storing more lipid droplets relative to N2 wild type as indicated by the more intense fluorescent staining (Fig. 4). Lipid stores in transgenic npr-9;quEx182 worms appeared similar to wild type (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

npr-9 mutants accumulate more fat. Nile red staining showing fat accumulation in wild type compared with npr-9(tm1652) mutants and the rescuing line (quEx182). Eighty-three percent (n = 12) of npr-9 mutants had greater fat staining than the strongest N2 (wild type) observed. The overexpressing npr-9 (quEx182) rescued the fat accumulation defect and was not significantly different to that of wild-type fat accumulation. Photographs are of 3-day-old adults. (Magnification: ×200.)

Discussion

Here, we report that NPR-9 has the highest degree of amino acid sequence identity (34–39%) with known insect allatostatin receptors and is expressed exclusively in the AIBL/R pair of interneurons and inhibits C. elegans local search behavior on food. The interneurons AIBL and AIBR are embryonic and born ≈300 min after the first cell division. Even though the AIB neuron is present in the embryo we did not observe npr-9:GFP expression until the L1 stage. The loss of the roaming behavior is not observed in npr-9 mutant L1 animals even though npr-9::GFP expression can be detected in L1 larvae. This observation suggests that C. elegans foraging behaviors may have different neuronal circuits in the larvae compared with the adults or that the circuit has not become competent until after this stage. The phenotype of npr-9 mutant was an exclusive local search and pivoting behavior on food. This phenotype resembles the “lurcher” worm. Transgenic (lurcher) worms, expressing an ionotropic glutamate receptor with a gain-of-function mutation, rapidly switch between short duration forward and backward movements. As such, lurcher worms have lost their roaming behavior and show an increased pivoting/local search behavior and thus do not travel a great distance in comparison to wild type (21). The sensory neurons' promoting forward and backward movements send their anatomical synaptic outputs from one to several of a subset of interneurons, namely AIA, AIB, AIY, and AIZ. Pivoting and local search behavior is stimulated by the AIB interneurons (24, 25). Ionotropic glutamate receptors mediate excitatory synaptic signaling between neurons. Because the GLR-1 ionotropic glutamate receptor is expressed in the AIB interneuron, NPR-9 may work antagonistically to GLR-1 to control foraging behavior. Our results are consistent with NPR-9 having inhibitory effects on AIB. First, the npr-9 mutants behave as if AIB is stimulated (increased pivoting and local search), and second, overexpression of NPR-9 mimics the AIB laser ablation phenotypes and glr-1 mutants (increased roaming and forward movement). Indirect evidence also suggests that neuropeptides in C. elegans inhibit glutamate release (26, 27). An evolutionary parallel exists between allatostatin and glutamate during the regulation of juvenile hormone biosynthesis in corpora allata of cockroaches. In this system the allatostatin receptor (9) and glutamate-gated chloride channels (28) function as inhibitors and the ionotropic glutamate receptors function as stimulators (29). In addition, the Drosophila allatostatin receptor can reversibly inactivate mammalian neurons in vivo (30).

In the absence of food, npr-9 mutants mimic the locomotory behavior of wild-type N2 animals. This observation demonstrates that npr-9 mutant behavior on food is a response to sensory input and is not caused by the animals being incapable of moving (uncoordinated phenotype). npr-9 mutant animals in the absence of food are still competent to move and respond to touch. The absence of food is thought to trigger sensory neuron ASK to send synaptic output to depolarize interneurons AIB/AIZ to switch to shortened forward movement and high angle turns to create rapid return to food behavior (24), which is consistent with laser ablation of AIZ and AIB. Loss of AIZ results in the reduced frequency of short reversals on food, whereas loss of AIB resulted in animals when removed from food having fewer long reversals and omega turns resulting in an increased duration of forward movement (24, 25). That forward movement is being inhibited in the npr-9 mutant is exemplified in the mutant rescue that resulted in gain-of-function that moves great distances off food but still attempts to return to food. This observation suggests that the ligand must be present in excess and the receptor is the limiting factor. In wild-type animals, the presence of food creates an “area restricted search” (ARS) behavior that is characterized by frequent reversals and sharp omega turns that function to maximize the time spent on an abundant food source. When the food supply is exhausted turning frequency decreases and the search area is increased. Dopamine released in response to food modulates glutamate signaling to regulate ARS turn frequency (31). The overexpressed receptor appears to override the dopamine/glutamate signaling of ARS behavior, supporting the close relationship of NPR-9 to glutamate signaling. In the npr-9 mutant fat accumulates at an accelerated rate relative to wild type or the rescued mutant, which may be caused by increased food uptake efficiency or decreased metabolic rate. As NPR-9 is related to the galanin receptor it is tempting to speculate that the neuropeptide interaction with this receptor resembles the action of galanin, which is known to act preferentially on ingestion of fat, reducing energy expenditure and thus increasing fat deposition (19). This increase in fat deposition in response to receptor loss is opposite to the decreased lipid found in either neuropeptide precursor processing enzyme mutant proprotein convertase EGL-3 or carboxypeptidase E EGL-21 (32). Loss of EGL-3 or EGL-21 function inhibits the correct processing of most neuropeptide precursors and thus likely disrupts numerous metabolic processes that may affect fat accumulation. As such, loss of EGL-3 or EGL-21 is not comparable to knocking out the single receptor NPR-9. The peptides that activate NPR-9 are as yet uncharacterized; however, C. elegans genes nlp-5 and nlp-6 are prime candidates as they encode polypeptide precursors that upon processing would release peptides that resemble allatostatin-like peptides (33). Either one or both may interact with NPR-9. Multiple peptides expressed from more than one gene has been noted for the flp receptor, NPR-1 that interacts with two flps, FLP-18 and FLP-21 (34, 35). A preliminary note has suggested that the nlp-5 mutant has altered locomotion on food (C. Bargmann, www.wormbase.org).

Materials and Methods

Nematodes Strains.

All nematode strains were maintained at 20°C on standard nematode growth medium plates with Escherichia coli strain OP50 (4). Nematode strains used include: N2, wild type; IC611, quEx128 [npr-9-gfp]; OH1098, (otIs133)[pttx-3::RFP + unc-4(+)], RFP expressed in AIY only (36); IC683, zk455.3 (tm1652) outcrossed 4×; and IC765, npr-9(tm1652);quEx182[.npr-9(+)].

Foraging Assays.

Animals were either synchronized and video-recorded at various stages of development, or 5 to 10 adults were picked to plates with an E. coli (OP50) spot (food) or plates that contained no food. After the transfer of animals they were left at 20°C for ≈30–60 min before scoring movement behavior. Animals were video-recorded by using time-lapsed software (HandyAvi version 3.2; Anderson's AZcendant Software) and a 5-megapixel USB microscope camera (DCM500A; www.scopetek.com). Frames were captured at either 1- or 10-s intervals from 10 min up to 12 h. To simplify our analysis we scored a roaming/searching behavior as positive if the animal moved beyond four body lengths of its original position within a 5-min interval. If the animals stayed within approximately a four-body length perimeter we scored it as a pivoting/local search behavior. A sample size of 30 animals or more was used in each assay.

Nile Red Staining.

Nile red visualization of intestinal fat content was as described (37). Animals were picked randomly and scored blindly. Animals were photographed 3 days after they reached adulthood under the same conditions and camera exposure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Sarah Slater for creating the GFP recombinant construct, Dr. Shohei Mitani (Tokyo Women's Medical University, Tokyo) for the tm1652 deletion allele, and Ahmed Mohamed for assistance and advice. Some nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (University of Minnesota, Twin Cities), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Center of Research Resources. This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council discovery grants (to W.G.B, I.D.C.-S., and S.S.T.). I.D.C.-S. is a Research Scientist of the Canadian Cancer Society through an award from the National Cancer Institute of Canada.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0709492105/DC1.

References

- 1.Husson SJ, Clynen E, Baggerman G, De Loof A, Schoofs L. Peptidomics of Caenorhabditis elegans: In search of neuropeptides. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 2005;70:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husson SJ, Mertens I, Janssen T, Lindemans M, Schoofs L. Neuropeptidergic signaling in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;82:33–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C. The ever-expanding neuropeptide gene families in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Parasitology. 2005;131(Suppl):S109–S127. doi: 10.1017/S0031182005009376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bargmann CI. Neurobiology of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Science. 1998;282:2028–2033. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birgul N, Weise C, Kreienkamp HJ, Richter D. Reverse physiology in Drosophila: Identification of a novel allatostatin-like neuropeptide and its cognate receptor structurally related to the mammalian somatostatin/galanin/opioid receptor family. EMBO J. 1999;18:5892–5900. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerswald L, Birgul N, Gade G, Kreienkamp HJ, Richter D. Structural, functional, and evolutionary characterization of novel members of the allatostatin receptor family from insects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:904–909. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenz C, Sondergaard L, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ. Molecular cloning and genomic organization of a novel receptor from Drosophila melanogaster structurally related to mammalian galanin receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:91–96. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DK, et al. Discovery of a receptor related to the galanin receptors. FEBS Lett. 1999;446:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendena WG, Donly BC, Tobe SS. Allatostatins: A growing family of neuropeptides with structural and functional diversity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;897:311–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tobe SS, Bendena WG. Allatostatins in The Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides. In: Kastin A, editor. New York: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodhead AP, Stay B, Seidel SL, Khan MA, Tobe SS. Primary structure of four allatostatins: Neuropeptide inhibitors of juvenile hormone synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5997–6001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobe SS, Zhang JR, Bowser PR, Donly BC, Bendena WG. Biological activities of the allatostatin family of peptides in the cockroach, Diploptera punctata, and potential interactions with receptors. J Insect Physiol. 2000;46:231–242. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(99)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange AB, Bendena WG, Tobe SS. The effect of the 13 Dip-Allatostatins on myogenic and induced contractions of the cockroach (Diploptera punctata) hindgut. J Insect Physiol. 1995;41:581–588. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reichwald K, Unnithan GC, Davis NT, Agricola H, Feyereisen R. Expression of the allatostatin gene in endocrine cells of the cockroach midgut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11894–11898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu CG, Stay B, Ding Q, Bendena WG, Tobe SS. Immunochemical identification and expression of allatostatins in the gut of Diploptera punctata. J Insect Physiol. 1995;41:1035–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stay B, Zhang JR, Tobe SS. Methyl farnesoate and juvenile hormone production in embryos of Diploptera punctata in relation to innervation of corpora allata and their sensitivity to allatostatin. Peptides. 2002;23:1981–1990. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuse M, et al. Effects of an allatostatin and a myosuppressin on midgut carbohydrate enzyme activity in the cockroach Diploptera punctata. Peptides. 1999;20:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YJ, et al. Central peptidergic ensembles associated with organization of an innate behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14211–14216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603459103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang R, Gundlach AL, Kofler B. The galanin peptide family: Receptor pharmacology, pleiotropic biological actions, and implications in health and disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:177–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiwara M, Sengupta P, McIntire SL. Regulation of body size and behavioral state of C. elegans by sensory perception and the EGL-4 cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron. 2002;36:1091–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng Y, Brockie PJ, Mellem JE, Madsen DM, Maricq AV. Neuronal control of locomotion in C. elegans is modified by a dominant mutation in the GLR-1 ionotropic glutamate receptor. Neuron. 1999;24:347–361. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Remy JJ, Hobert O. An interneuronal chemoreceptor required for olfactory imprinting in C. elegans. Science. 2005;309:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1114209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bargmann C. Neuroscience: Comraderie and nostalgia in nematodes. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R832–R833. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakabayashi T, Kitagawa I, Shingai R. Neurons regulating the duration of forward locomotion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Neurosci Res. 2004;50:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray JM, Hill JJ, Bargmann CI. A circuit for navigation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3184–3191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409009101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kass J, Jacob TC, Kim P, Kaplan JM. The EGL-3 proprotein convertase regulates mechanosensory responses of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9265–9272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09265.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellem JE, Brockie PJ, Zheng Y, Madsen DM, Maricq AV. Decoding of polymodal sensory stimuli by postsynaptic glutamate receptors in C. elegans. Neuron. 2002;36:933–944. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu HP, Lin SC, Lin CY, Yeh SR, Chiang AS. Glutamate-gated chloride channels inhibit juvenile hormone biosynthesis in the cockroach, Diploptera punctata. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:1260–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang AS, et al. Insect NMDA receptors mediate juvenile hormone biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:37–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012318899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan EM, et al. Selective and quickly reversible inactivation of mammalian neurons in vivo using the Drosophila allatostatin receptor. Neuron. 2006;51:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hills T, Brockie PJ, Maricq AV. Dopamine and glutamate control area-restricted search behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1217–1225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Husson SJ, et al. Impaired processing of FLP, NLP peptides in carboxypeptidase E (EGL-21)-deficient Caenorhabditis elegans as analyzed by mass spectrometry. J Neurochem. 2007;102:246–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathoo AN, Moeller RA, Westlund BA, Hart AC. Identification of neuropeptide-like protein gene families in Caenorhabditis elegans and other species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14000–14005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241231298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers C, et al. Inhibition of Caenorhabditis elegans social feeding by FMRFamide-related peptide activation of NPR-1. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1178–1185. doi: 10.1038/nn1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geary TG, Kubiak TM. Neuropeptide G protein-coupled receptors, their cognate ligands and behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hobert O, et al. Regulation of interneuron function in the C. elegans thermoregulatory pathway by the ttx-3 LIM homeobox gene. Neuron. 1997;19:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashrafi K, et al. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature. 2003;421:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nature01279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.