Abstract

Leaf venation is a showcase of plant diversity, ranging from the grid-like network in grasses, to a wide variety of dendritic systems in other angiosperms. A principal function of the venation is to deliver water; however, a hydraulic significance has never been demonstrated for contrasting major venation architectures, including the most basic dichotomy, “pinnate” and “palmate” systems. We hypothesized that vascular redundancy confers tolerance of vein breakage such as would occur during mechanical or insect damage. We subjected leaves of woody angiosperms of contrasting venation architecture to severing treatments in vivo, and, after wounds healed, made detailed measurements of physiological performance relative to control leaves. When the midrib was severed near the leaf base, the pinnately veined leaves declined strongly in leaf hydraulic conductance, stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic rate, whereas palmately veined leaves were minimally affected. Across all of the species examined, a higher density of primary veins predicted tolerance of midrib damage. This benefit for palmate venation is consistent with its repeated evolution and its biogeographic and habitat distribution. All leaves tested showed complete tolerance of damage to second- and higher-order veins, demonstrating that the parallel flow paths provided by the redundant, reticulate minor vein network protect the leaf from the impact of hydraulic disruption. These findings point to a hydraulic explanation for the diversification of low-order vein architecture and the commonness of reticulate, hierarchical leaf venation. These structures suggest roles for both economic constraints and risk tolerance in shaping leaf morphology during 130 million years of flowering plant evolution.

Keywords: herbivory, evolution, physiology, plant traits, hydraulic architecture

Many essential aspects of flowering plant form have undergone repeated evolutionary transitions, with key examples including the frequent shifts between polysymmetry and monosymmetry in flowers (1, 2) and numerous divergences in the architecture of major leaf veins. The major vein network provides hydraulic supply and mechanical support to the leaf lamina, and is highly diverse across species, ranging from grid-like in grasses to a wide variety of dendritic systems in dicotyledons (3). Previous theoretical work has proposed advantages for various venation systems in terms of their construction costs relative to biomechanical support for given leaf shapes and sizes (4–7). However, no hydraulic significance has been demonstrated for divergent architectures (8), including the most basic dichotomy, pinnate versus palmate venation. Pinnately veined species, with a single first-order vein, are most common, but palmately veined species, with multiple first-order veins branching from the petiole, account for up to 30% of regional floras (9). We inferred that palmate venation confers a hydraulic benefit under certain conditions, because it has evolved many times in different lineages (10), despite its relatively high construction and maintenance cost (11).

The leaf venation system can influence leaf and whole-plant hydraulic conductance (Kleaf and Kplant respectively; 12–15). Under a given transpiration rate, Kplant, which is constrained by Kleaf, determines the degree to which stomata may remain open, thus limiting gas exchange and plant growth (14, 16). Kleaf is in turn determined by both the structure of the vein xylem and the “extraxylem” pathways of water movement from the veins to the leaf airspaces (14, 17). However, Kleaf is independent of major vein density (vein length per area) in intact leaves. As for optimized irrigation systems (18, 19), the major veins act as high-capacity lateral-supply “mainlines” (20–23), with the total numbers and dimensions of xylem conduits determining conductance, regardless of major vein density (13, 24–26). In contrast, the minor vein system acts as a “distribution network,” in which higher density increases conductance by providing a greater surface for water transfer to the mesophyll (14). Nevertheless, major vein density might have hydraulic consequences in damaged leaves. Although leaves can often survive midrib vein damage while remaining green and turgid (27), they may suffer reduced Kleaf, stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic rate, immediately, and weeks later, after the damage has healed (22, 28–34). The reticulation of venation has been hypothesized to reduce the impact of disruption by providing transport around damaged veins (35, 36). We hypothesized that high vein density (“redundancy”) might also provide tolerance of damage, and that this principle may thus have played a role in the evolution of palmately veined leaves. To explore this hypothesis we subjected leaves of a range of contrasting venation architectures to standardized damage treatments in vivo, including severing of the midrib and higher-order veins, and after wounds had healed, determined the impacts on leaf function.

Results

Impacts of Severing the Midrib on Leaf Function for Pinnately Versus Palmately Veined Leaves.

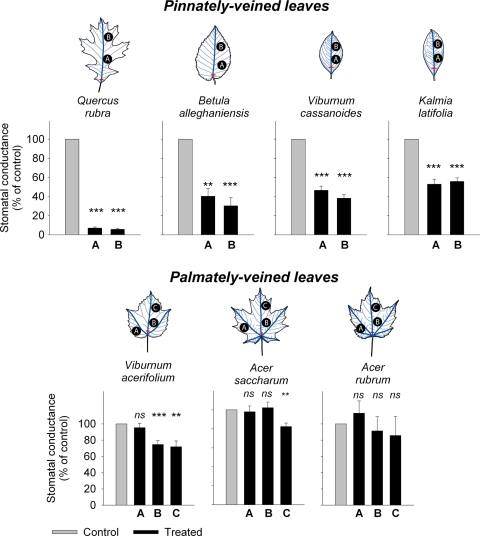

In all of the treatments the treated leaves survived as well as the controls for all species (0–6% mortality for each species; 3% on average; P > 0.17, paired t tests). However, severing the midrib had strong impacts on physiological function. Pinnately veined species with severed midribs showed profound reductions in stomatal conductance (g), measured 2–9 weeks after the cuts had healed (Fig. 1). Reductions in g were substantial across the leaf, ranging from (mean ± SE) 46% ± 4.4% for Kalmia latifolia to 94% ± 1.1% for Quercus rubra (Fig. 1). Palmately veined species with severed midribs showed much lower reductions in g, with the reductions strongly dependent on location; there was no impact at the marginal lobes, and a significant although weaker reduction of g in both central lamina locations (Fig. 1). Although g was reduced in the proximal half of the central lamina by 25% ± 5.0% on average for Viburnum acerifolium, it was not significantly reduced for Acer rubrum and Acer saccharum; in the distal half of the central lamina, g was reduced by 18% ± 3.8% for A. saccharum and 28% ± 7.1% for V. acerifolium (Fig. 1). The reduction of g was 63% ± 10% and 10% ± 8.1% for pinnately and palmately veined species, respectively, in the proximal half of the central lamina, and 68% ± 10% and 20% ± 4.1% in the distal half.

Fig. 1.

The impact of severing the midrib on stomatal conductance for pinnately and palmately veined species, relative to untreated leaves, with tested species arranged in order of increasing tolerance. Measurements of g were made at the lamina locations indicated; mean values ± standard errors presented (n = 9–15). The leaf schematics show the severed midrib in red and the first- and second-order veins in dark and light blue, respectively. Palmately and pinnately veined systems differed significantly in the impact of the treatment on g (ANOVAs with species nested within venation type; for each of the two central locations, venation type and species, P < 0.001; df = 85–86). For pinnately veined species, reductions were significant across the leaf (repeated-measures ANOVA; species effect, P < 0.001; location effect, P = 0.057; interaction, P = 0.12; df = 87). For palmately veined species the reduction of g depended strongly on location (species effect, P = 0.399; location effect, P < 0.001; species × location, P = 0.351); there was no impact at the marginal lobes and a significant although relatively weak reduction of g in both central lamina locations (species P < 0.001 and treatment P ≤ 0.006 for the central lamina locations, P = 0.548 for the marginal lobe; species × treatment interaction, P = 0.118–0.76; df = 84–85). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns = not significant at P < 0.05 (paired t tests on ln-transformed data for each location for species tested individually).

Pinnately and palmately veined species also differed in the impacts of the severed midrib on transpiration (Eleaf), the water potential drop across the leaf (ΔΨleaf), and Kleaf (supporting information (SI) Fig. 3). Pinnately veined species with severed midribs showed a reduction in Eleaf ranging from 43% ± 4.2% for K. latifolia to 90% ± 1.7% for Q. rubra (paired t tests, P ≤ 0.001; n = 5–8), a reduction in Kleaf ranging from 62% ± 7.9% for K. latifolia to 95% ± 1% for Q. rubra (P ≤ 0.005; n = 5), and an increase in ΔΨleaf ranging from 34% ± 11% for Viburnum cassanoides to 100% ± 15% for Q. rubra (P ≤ 0.03; n = 5–6); on average, for the three pinnately veined species, severing the midrib drove reductions of Kleaf and Eleaf by 75% ± 10% and 63% ± 14%, respectively, and an increase of ΔΨleaf by 66% ± 19% (SI Fig. 3). By contrast, palmately veined species with severed midribs showed a reduction of Eleaf by 9% ± 4.1%, significant only for V. acerifolium tested individually (reduction of 15% ± 4.4%; paired t test, P = 0.007; n = 12), but no overall impact on Kleaf or ΔΨleaf (SI Fig. 3).

Across species, the ability to maintain g with a severed midrib (relative to control leaves) correlated with the ability to maintain Kleaf, whether g was measured in the proximal or distal half of the leaf (rs = 0.84–0.94, P = 0.005–0.036; rp = 0.93–0.95, P = 0.004–0.008; n = 6).

We found similar impacts of midrib severing on photosynthetic capacity for A. saccharum and Q. rubra, as assessed by measuring the quantum yield of photosystem II (ΦPSII; SI Fig. 4). Pinnately veined Q. rubra showed a statistically nonsignificant 32% ± 21% reduction of ΦPSII in the proximal half of the leaf, and a significant 54% ± 13% reduction in the distal half, whereas A. saccharum showed no significant reductions (SI Fig. 4).

Differences Across Species in Venation Architecture Explain Tolerance to Midrib Damage.

Species differed strongly in venation architecture, ranging 4-fold in the densities of 1° and 2° veins (SI Fig. 5 A–C). Across species, 1° and 2° vein densities were uncorrelated (SI Fig. 5A), and the combined 1° and 2° vein density was driven by the 2° vein density (rs = 0.96; rp = 0.98; P < 0.001) but not the 1° vein density (SI Fig. 5B). In the pinnately veined species larger leaves had lower 1° and 2° vein densities (for log-transformed data, rs = −0.88 to −0.98, P = 0.016–0.12; rp = −0.98 to −0.99; P = 0.010–0.023; n = 4). Species ranged 9-fold in the density of 1° and 2° veins remaining functional after the midrib was severed (SI Fig. 5C). Because of the hierarchical nature of the venation system, the density of 1° and 2° veins remaining functional after the midrib was severed related to the density of 1° veins in the intact leaf (in absolute terms, or as a percentage of the intact density; SI Fig. 5C), and not to the density of 2° veins, nor the combined density of 1° and 2° veins in the intact leaf (rs = −0.18–0.36, P = 0.43–0.70; rp = −0.20–0.27; P = 0.56–0.98).

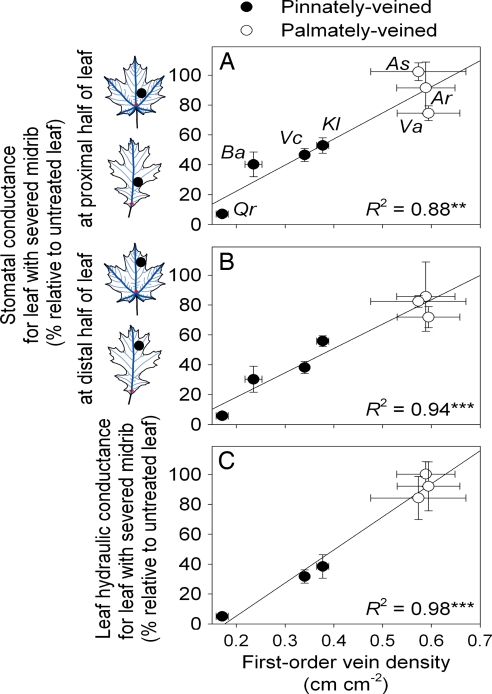

Across species, the impacts of severing the midrib depended on the redundancy of the major veins (Fig. 2 A–C). The ability to maintain a high g and Kleaf despite a severed midrib (relative to untreated leaves) correlated with the 1° and 2° vein density remaining functional, individually and combined, in absolute terms, and as a percentage of the intact density (rs = 0.79–0.96, P ≤ 0.001 to 0.06; rp = 0.85–0.97; P ≤ 0.03). Consistent with the hierarchical arrangement of the venation network, the ability to maintain g and Kleaf despite a severed midrib correlated with the original density of 1° veins in the intact leaf (Fig. 2 A–C), but not with the original density of 2° veins, nor with the combined density of 1° and 2° veins in the intact leaf (rs = 0.14–0.39, P = 0.38–0.76; rp = −0.16–0.29; P = 0.52–0.93).

Fig. 2.

The ability of leaves with severed midribs to maintain hydraulic function is predicted by venation architecture. The ability to maintain stomatal conductance at the proximal (A) and at the distal (B) halves of the leaf relative to untreated leaves (shown schematically for leaves of A. saccharum and Q. rubra, examples of palmately and pinnately veined leaves, respectively), and the ability to maintain whole-leaf hydraulic conductance (C) were related to the primary vein density (rs = 0.86–0.94, P ≤ 0.014; rp = 0.94–0.99; P ≤ 0.002). Mean values ± standard errors presented (n values: 9–15 for stomatal conductance; 5–10 for leaf hydraulic conductance; 5 for venation density). Species symbols: Ar, Acer rubrum; As, Acer saccharum; Ba, Betula alleghaniensis; Kl, Kalmia latifolia; Qr, Quercus rubra; Va, Viburnum acerifolium; and Vc, Viburnum cassanoides. Parameters of linear regressions, y = a + bx: (A) a = −0.126 ± 0.125, b = 17.5 ± 2.82; (B) a = −0.142 ± 0.0827, b = 16.3 ± 1.87; (C) a = −0.388 ± 0.0827, b = 22.1 ± 1.77. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Impacts of Severing 2°, 3°, and Higher-Order Veins on Leaf Function.

Severing higher-order veins had minimal impacts on leaf function (SI Figs. 6 and 7). Disrupting a 2° vein had no impact on g, ΦPSII, Eleaf, ΔΨleaf, or Kleaf for any of the species tested (SI Fig. 6). Additionally, we found no differences between punching 5 versus 10 holes in the lamina, treatments that severed 3° and minor veins, for any measured parameter(SI Fig. 7; the data were pooled for further analyses); neither treatment had a significant impact on g, Eleaf, ΔΨleaf, or Kleaf for the eight species tested (SI Fig. 7). We found no impacts on ΦPSII adjacent to the hole, or in the uncut lobe (SI Fig. 7), and an average reduction of 2.9% ± 0.8% on the hole itself, similar to the proportion of scarred lamina in the instrument measurement area (≈3.5 mm2 of the 0.785 cm2), and significant only for A. saccharum tested individually (reduction of 3.6% ± 0.62%; SI Fig. 7).

Discussion

Our experiments showed that redundancy in the leaf venation system contributes strongly to tolerance of vein damage. Redundancy in 1° veins, as provided by palmate venation, allows leaves to maintain g, Kleaf, and ΦPSII despite a severed midrib. Even pinnately veined species with relatively high 1° vein density, due to their smaller leaf size, showed stronger tolerance of vein damage. When the midrib was severed, these leaves had a greater number of functional 2° veins branching proximal to the cut and maintaining supply to the minor vein network. Across species, tolerance of damage was directly proportional to the 1° vein density in the intact leaf, and to the percentage of major vein density remaining functional after the treatment (Fig. 2).

The decline in function caused by severing the midrib for pinnately veined species was consistent with previous studies of at least 13 species (22, 28–34). We found that damage tolerance was greater for leaves with greater 1° vein redundancy. Vein redundancy would provide tolerance for the biomechanical (37), phloem (22, 38), and hydraulic systems. The tolerance of the hydraulic system is especially important; in previous work on pinnately veined Prunus laurocerasus, g and Kleaf declined colinearly in response to increasingly severe midrib blockage (31). We found a similar correlated decline of g and Kleaf across species with diverse venation architecture, subjected to standardized midrib damage. The decline of Kleaf most likely derived from the spread of irreversible xylem embolism during the treatment and subsequently, and later blockage of xylem by tyloses (16, 22, 39). During natural transpiration, damaged leaves would face strong declines in Ψleaf and increases in ΔΨleaf, leading to mitigatory stomatal closure and depressed photosynthetic rate (14, 31, 40), and increased evaporation from the cut edges would contribute to further tissue desiccation for several days (22, 29, 33, 41, 42).

The impact of midrib damage in a pinnately veined leaf would depend on the distance along the midrib at which severing takes place. Severing the midrib of a pinnately veined leaf does not affect lamina proximally to the cut, but would lead to embolism of vessels that branch into 2° and 3° veins distal to the cut (22, 29, 33). Thus, pinnately veined leaves with midribs severed closer to the base would develop greater reductions of Kleaf and of gas exchange distal to the cut, as fewer veins branch off proximally to the cut and maintain their function, and a greater distal area of leaf lamina would be affected (29–31, 33, 43). However, palmately veined leaves with midribs severed near the leaf base showed minimal reduction of function in only the distal central lamina. Thus, whereas palmately veined leaves have higher 1° vein density, and thus a potentially higher likelihood of damage to 1° veins, their venation architecture protects their hydraulic system from the impact of this damage.

In all tested species the high density and reticulation of 2° and higher-order veins provided these vein orders with complete damage tolerance. This finding does not necessarily imply that minor venation is overbuilt hydraulically; in fact, the allocation cost should limit minor vein density to that required for hydraulic capacity (24, 27, 44). Apparently, high-density reticulate minor venation provides damage tolerance as an added benefit (45).

The tolerance of the vein system may be especially important in relation to the threat imposed by insects. We found that palmately veined leaves tolerate midrib damage, as can be inflicted generally by insects in several orders, which have converged on this behavior as part of feeding (e.g., 29, 30, 33, 46). All of the study species withstood severing of higher-order veins with little impact. The general benefit provided by venation architecture would be important even against the background of complex plant responses. Some species can compensate for partial leaf damage through increased photosynthetic rate in the lamina surrounding the damage (30, 47); other species experience reduced photosynthetic rates in surrounding lamina (48); and yet other species, including those in this study, show only minor effects immediately adjacent to the removed lamina (22, 29, 41, 42). In addition, some species can partially compensate at whole-plant level, with undamaged leaves or subsequently expanded leaves increasing their photosynthetic rate (49, 50). However, major lamina loss would lead to depression of growth and of overall fitness (49, 50), and vein redundancy, providing substantial tolerance, would thus contribute to plant performance despite these complexities. Vein redundancy might also confer tolerance of other types of vein dysfunction, such as occlusion by bacterial pathogens (32), or by drought- or freeze/thaw-induced xylem embolism (31, 34, 43). We note that lower-order veins contain numerous xylem conduits in parallel, which provide another level of redundancy; blockage by bacteria or emboli may occur in some but not all xylem conduits (22, 51). The redundancy of conduits within veins, together with that of major veins shown in this study, would lead to a strong capacity to tolerate vein xylem blockage.

The benefit of redundant venation must exceed its cost. The multiple 1° veins in palmate leaves are expensive, entailing higher mass allocation to the veins relative to photosynthetic mesophyll (11), and a less efficient mechanical support per mass investment in these veins (5). We expect that the damage tolerance provided by palmate venation should be most advantageous for thin or short-lived leaves, because thick, tough leaves would already be protected against damage regardless of their venation architecture (52, 53). The more expensive protection provided by general thickening would presumably be most beneficial in long-lived leaves subject to higher lifetime levels of herbivory (53, 54). The biogeographic distribution and habitat association of leaf venation types supports this hypothesis. Palmately veined species are more common in regional floras of the temperate zone than the tropical zone (26% vs. 17%, n = 6; P < 0.001; our analysis of data of ref. 9); plants of the temperate zone have thinner leaves on average (54, 55). Even in tropical floras, palmate venation tends to occur in pioneer species with relatively thin, large, short-lived leaves that also tend to be exposed to insect damage, high-evaporative loads, and potential leaf desiccation as juveniles (56). Palmate venation is also common in other types of thin laminae, including cotyledons and sepals, petals, and bracts (9). We note that there is an alternative, third approach to protecting the leaf—thin, pinnately veined leaves may especially protect their midrib. Indeed, leaves tend to invest midribs with relatively thick cell walls, and sometimes with laticifers and secondary chemistry, which can render the midrib less palatable (46, 57); on average, pinnately veined species tend to allocate a greater proportion of their mass to the midrib than palmately veined species (11). Additional investigation is needed of the costs and effectiveness of these alternatives for protecting the leaf.

Palmately veined leaves may have other advantages in addition to greater damage tolerance. Selection for larger leaf size may favor the evolution of broad, palmately veined leaves. Palmately veined leaves may require a lower investment in 2° veins, allowing a lower venation construction cost for a given biomechanical support (4, 7). Further work is needed to determine the relative importance of these benefits to carbon balance integrated across the whole leaf lifetime, across varying ecological conditions (58, 59). One or more strong functional roles for major venation architecture would explain its diversification. The ancestral flowering plants most likely had pinnate venation, and evolutionary shifts to palmate venation, and reversals, appear in numerous families (e.g., 10, 60–64), with additional transitions obscured by extinctions (56, 65). Theoretically, the shifts may arise due to mutation of one or a few genes that alter the sequence or timing of leaf form development (10, 66, 67). However, within lineages, venation type tends to be phylogenetically conserved (e.g., 10, 61–64), suggesting that transitions are rare relative to speciation and extinction events (68). The conservatism of venation type within lineages may have resulted from stabilizing selection in similar or convergent habitats. Alternatively, the conservatism may be due to genetic or developmental obstacles to the evolution of venation type (69). Indeed, venation topology mutants are rare in natural or mutagenized populations (70, 71), possibly because of genetic and/or developmental redundancy, or alternatively, because of constraints, such that mutations are lethal, especially if other important features have evolved a developmental or functional dependence on the specific vein topology (69, 71–75). Shifts to palmate venation may thus arise because of rare viable mutations that become rapidly fixed according to strong benefit in certain habitats. Coevolutionary theory would predict that vein redundancy, by contributing to insect tolerance, might itself promote diversification (76, 77).

We found that venation architecture has a key significance for whole-plant function. Notably, in this study, coexisting species were selected for variation in leaf size, shape, and venation, and analyses could not be conducted within a phylogenetic framework; future work is needed to confirm the findings with phylogenetically independent contrasts (78, 79). The importance of the leaf venation architecture in hydraulic function, and its variation in construction cost and biomechanical effectiveness invites studies of differentiation across the great diversity of angiosperm systems. The damage tolerance conferred by leaf vascular redundancy would have contributed to the ability of flowering plants and their ecosystems to sustain productivity, despite damage and heavy insect loads, through their 130 million years of evolution (42, 48, 53).

Materials and Methods

Study Site and Species.

We performed the experiments at Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts (42°54′ N, 72°18′ W), on eight species of trees and shrubs, 1–5 m tall, located along roads and trails throughout the forest, diverse in venation architecture and leaf size (SI Table 1). Experimental leaves were those of highest exposure that could be accessed by hand from the ground. As an index of the light environment, we measured the diffuse site factor (dsf; 80) on an overcast day for five to seven experimental leaves per tree relative to a nearby clearing; dsf values (mean ± SE) ranged from 7.5% ± 1.7% for K. latifolia to 39.6% ± 3.0% for A. rubrum (SI Table 1).

Treatments.

Leaf veins were classified according to branching architecture (70). The 1° vein(s) connect directly to the petiole, the 2° veins branch from the 1° vein(s), and the 3° veins are smaller in diameter, branching from and sometimes linking the 1° and 2° veins. The higher-order “minor veins” are of a range of smaller diameters, forming a continuous mesh with the major veins.

We applied four treatments, partially severing different portions of attached leaves, by using a scalpel or cork borer while supporting the leaf on a Styrofoam block. The first treatment consisted of a cut across the midrib, 1 cm from the petiole-lamina junction (applied to seven species; Fig. 1). For pinnately veined species we splinted the leaves in place to prevent mechanical collapse by taping a 2.5 × 9 cm piece of white cardboard, folded over the top of the petiole and base of the lamina; for palmately veined leaves, the large leaf base precluded splinting in this way, and we taped over the cut abaxially and adaxially with a 1.7-cm2 square of white, waterproof medical tape (First-Aid Tape 5050, Johnson & Johnson; see Statistics below). A second treatment consisted of severing a central 2° vein, 3–5 mm from its branch point with the midrib (applied to five species; SI Fig. 6). The third and fourth treatments consisted of punching 5 and 10 holes, respectively, of 0.24 cm2 (0.55-cm diameter) centrally in the lamina, avoiding 1° and 2° veins and severing only 3° and minor veins (applied to eight species; SI Fig. 7). We applied treatments to five leaves on each of three plants for all species (except seven leaves of each of two trees for V. acerifolium) from June 19 to July 22, 2002. We paired each treated leaf with a control leaf nearby on the same branch that was matched approximately in size and exposure; control leaves were left uncut, but were splinted and taped as for the treated leaves.

Physiological Measurements.

Gas exchange.

We made physiological measurements 2–9 weeks after the treatments, at which time the cuts had healed over. From July 11 to August 28, 2002, we measured g, E, and leaf temperature by using a steady-state porometer (LI-1600; LI-COR). We covered the cuvette top with clear plastic, sealed with tape, to allow measurements of tissue surrounding leaf holes. We made all measurements between 1000 and 1600 hours, alternating treated leaves with their matched controls. We made measurements at several lamina locations. For pinnately veined leaves subjected to severing of the midrib, we made measurements at two locations between the midrib and margin—in the center of the proximal half of the leaf and in the center of the distal half. For palmately veined leaves, we made measurements additionally in the center of the marginal lobe. For leaves subjected to severing of a 2° vein, we made measurements at two locations on the leaf—on the cut side, between the cut 2° vein and the margin; and on the uncut side, in the analogous position. For leaves subjected to hole punches, we made measurements directly adjacent to a punched hole, and with the cuvette centered on a hole, and, for palmately veined leaves, also on the most marginal lobe, which was left intact. For measurements that were made centered on the holes, we corrected g for the 0.24-cm2 area of missing lamina.

To test for potential changes in treatment impact over time, we made two sets of measurements of g (2–3 weeks and 4–9 weeks after the treatments) for A. saccharum and Q. rubra (all treatments), and for K. latifolia (the severing of 2° veins and severing of higher-order veins). For each species, the impact of the treatments on g at each lamina location was statistically similar at two measurement sessions (P > 0.05; paired t tests, n = 7–30); the findings reported in this article are for the second, final set of measurements.

We made measurements of the impacts of the treatments on the quantum yield of photosystem II (ΦPSII; Walz MINI-PAM; Heinz Walz GmbH; 81) for A. saccharum and Q. rubra, for all treatments, and, additionally, for K. latifolia and V. alnifolium, for the 2° and higher-order vein severing treatments, 2–3 weeks after the treatments were applied (4–15 leaves from each treatment).

Leaf hydraulic conductance.

We determined leaf hydraulic conductance (Kleaf) for leaves from each treatment and their paired controls after the final gas-exchange measurements, from two experimental trees of six species (SI Fig. 3). We estimated the pressure drop across the leaf (ΔΨleaf) as the difference between the water potential of a transpiring leaf and that of a matched nontranspiring (bagged) leaf, which before excision would have equilibrated with the xylem proximal to the petiole (82; determined by using a pressure chamber; Plant Moisture Stress Instrument Co.). We calculated Kleaf as E estimated by the porometer divided by ΔΨleaf (12, 22, 83, 84; see SI Text), and standardized for the effects of temperature on the viscosity of water by correcting to 25°C (85). Kleaf estimated by using these methods contains some degree of uncertainty, because porometers sometimes overestimate transpiration (12, 85); however, the values are sufficiently robust to allow comparisons of the impacts of the treatments relative to untreated controls (12, 22, 83–85).

Analysis of Major Vein Density.

We analyzed the major vein densities (length/area) for five leaves scanned per species (Epson Perfection 3170; Epson; ImageJ freeware; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). We estimated the density of 1° and 2° veins remaining potentially functional after the midrib was severed by assuming that the treatment and subsequent embolism would render largely nonfunctional the xylem in the midrib and in the 2° veins that branched distally to the cut (28). The 1° and 2° veins branching proximally to the cut are partly supplied by independent xylem conduits from the petiole, which would not have embolized when the midrib was severed (9, 24, 86).

Statistics.

To test the physiological impact of each treatment, we first analyzed data for given lamina locations for all species of each leaf type together by using repeated-measures ANOVAs (using GenStat 9th edition, VSN International; factors species × treatment; 87–89), comparing treatment with matched control leaves. To compare palmately and pinnately veined species, we analyzed impact indices for given lamina locations, ln[(treated leaf/control leaf value) + 1], by using ANOVAs, with species nested within venation type (using Minitab Release 14; Minitab, State College, PA). We tested impacts for species individually by using paired t tests, comparing measurements at given lamina locations for treated and control leaves (87; Minitab Release 14). To test the difference between hole-punching treatments, or between measurements at different lamina locations, or at different times, we analyzed impact indices by using repeated-measures ANOVAs (with factors species and treatment or measurement location or time), blocking for leaf, followed by pairwise testing by orthogonal contrasts (GenStat 9th edition; 88, 89). We ln-transformed data before all tests to model for multiplicative effects and to increase normality and heteroscedasticity (88, 89). We performed Pearson and Spearman correlations and regression analyses to test for associations among variables (Minitab Release 14; 87, 89).

Species varied in their field microclimate, and thus we did not compare species in their absolute values for physiological parameters, but rather in their responses to treatments relative to untreated leaves. For the midrib-severing treatment, the splinting was by necessity different between palmate- and pinnate-veined species, and we compared species in their responses to treatments relative to control leaves that were splinted identically for each species. Additionally, we tested whether splinting would affect the findings for g, by comparing the splinted “control” leaves from the midrib severing treatment with the unsplinted “control” leaves from the other treatments; splinting had no significant impact, and no significant interaction with leaf type (P = 0.62 and 0.77 respectively; two-way ANOVA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank the staff and students of Harvard Forest for logistical support, K. Frole for assistance with data compilation, and H. Cochard, S. Davies, E. Edwards, T. Givnish, P. Grubb, C. Jones, A. Nicotra, Ü. Niinemets, and P. Wilf for helpful discussion and/or comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by an Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University Putnam Fellowship (to L.S.), the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and National Science Foundation Grants IOS-0546784 and 0139495.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.A. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0709333105/DC1.

References

- 1.Endress PK. Int J Plant Sci. 1999;160:S3–S23. doi: 10.1086/314211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howarth DG, Donoghue MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9101–9106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602827103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leaf Architecture Working Group. Manual of Leaf Architecture: Morphological Description and Categorization of Dicotyledonous and Net-veined Monocotyledonous Angiosperms. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Givnish TJ. Acta Biotheor. 1978;27:83–142. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Givnish TJ. In: Topics in Plant Population Biology. Solbrig OT, Jain S, Johnson GB, Raven PH, editors. New York: Columbia Univ Press; 1979. pp. 375–407. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Givnish TJ, Pires JC, Graham SW, McPherson MA, Prince LM, Patterson TB, Rai HS, Roalson EH, Evans TM, Hahn WJ, et al. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2005;272:1481–1490. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Givnish TJ. In: Physiological Ecology of Plants of the Wet Tropics. Medina E, Mooney HA, Vázquez-Yánes C, editors. The Hague: Dr. W. Junk; 1984. pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth-Nebelsick A, Uhl D, Mosbrugger V, Kerp H. Ann Bot. 2001;87:553–566. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinnott EW, Bailey IW. Am J Bot. 1915;2:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.White DA. J Theor Biol. 2005;235:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niinemets Ü, Portsmuth A, Tobias M. Funct Ecol. 2007;21:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sack L, Tyree MT. In: Vascular Transport in Plants. Holbrook NM, Zweiniecki MA, editors. Oxford: Elsevier/Academic; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nardini A, Gortan E, Salleo S. Funct Plant Biol. 2005;32:953–961. doi: 10.1071/FP05100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sack L, Holbrook NM. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:361–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodribb TJ, Feild TS, Jordan GJ. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1890–1898. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyree MT, Zimmermann MH. Xylem Structure and the Ascent of Sap. Berlin: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochard H, Nardini A, Coll L. Plant Cell Environ. 2004;27:1257–1267. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand M, Weaire D. Phys Rev E. 2004;70 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.046125. 046125-1–046125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuenca RH. Irrigation System Design: an Engineering Approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sack L, Streeter CM, Holbrook NM. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1824–1833. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.031203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zwieniecki MA, Melcher PJ, Boyce CK, Sack L, Holbrook NM. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:1445–1450. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sack L, Cowan PD, Holbrook NM. Am J Bot. 2003;90:32–39. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altus DP, Canny MJ. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1985;12:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sack L, Frole K. Ecology. 2006;87:483–491. doi: 10.1890/05-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aasamaa K, Sober A, Rahi M. Aust J Plant Physiol. 2001;28:765–774. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker P, Tyree MT, Tsuda M. Tree Physiol. 1999;19:445–452. doi: 10.1093/treephys/19.7.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plymale EL, Wylie RB. Am J Bot. 1944;31:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huve K, Remus R, Luttschwager D, Merbach W. Plant Biol. 2002;4:603–611. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldea M, Hamilton JG, Resti JP, Zangerl AR, Berenbaum MR, DeLucia EH. Plant Cell Environ. 2005;28:402–411. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oleksyn J, Karolewski P, Giertych MJ, Zytkowiak R, Reich PB, Tjoelker MG. New Phytol. 1998;140:239–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nardini A, Salleo S. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:1213–1219. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorne ET, Stevenson JF, Rost TL, Labavitch JM, Matthews MA. Am J Enol Vitic. 2006;57:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delaney KJ, Higley LG. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:1245–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salleo S, Raimondo F, Trifilo P, Nardini A. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:1749–1758. doi: 10.1111/pce.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner WH. Taxon. 1979;28:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohn S, Andreotti B, Douady S, Munzinger J, Couder Y. Phys Rev E. 2002;65 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.061914. 061914-1–061914-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niklas KJ. New Phytol. 1999;143:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wylie RB. Am J Bot. 1938;25:567–572. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salleo S, Nardini A, Lo Gullo MA, Ghirardelli LA. Biol Plant. 2002;45:227–234. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franks PJ, Drake PL, Froend RH. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:19–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang JY, Zielinski RE, Zangerl AR, Crofts AR, Berenbaum MR, DeLucia EH. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:527–536. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aldea M, Hamilton JG, Resti JP, Zangerl AR, Berenbaum MR, Frank TD, DeLucia EH. Oecologia. 2006;149:221–232. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nardini A, Tyree MT, Salleo S. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1700–1709. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durand M. Phys Rev E. 2006;73 016116. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohn S, Magnasco MO. 2006 http://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0607819.v1.

- 46.Dussourd DE, Denno RF. Ecology. 1991;72:1383–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Planta. 1984;160:320–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00393413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zangerl AR, Hamilton JG, Miller TJ, Crofts AR, Oxborough K, Berenbaum MR, de Lucia EH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1088–1091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022647099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avila-Sakar G, Stephenson AG. Int J Plant Sci. 2006;167:1021–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Honkanen T, Haukioja E, Suomela J. Funct Ecol. 1994;8:631–639. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bucci SJ, Scholz FG, Goldstein G, Meinzer FC, Sternberg LDL. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26:1633–1645. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edwards C, Read J, Sanson G. Oecologia. 2000;123:158–167. doi: 10.1007/s004420051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coley PD, Barone JA. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1996;27:305–335. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilf P, Labandeira CC, Johnson KR, Coley PD, Cutter AD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6221–6226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111069498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larcher W. Physiological Plant Ecology. 4th Ed. Berlin: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carpenter RJ, Hill RS, Scriven LJ. Int J Plant Sci. 2006;167:1049–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choong MF. Funct Ecol. 1996;10:668–674. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Givnish TJ. Taxon. 2003;53:273–296. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, Ackerly DD, Baruch Z, Bongers F, Cavender-Bares J, Chapin T, Cornelissen JHC, Diemer M, et al. Nature. 2004;428:821–827. doi: 10.1038/nature02403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feild TS, Arens NC. New Phytol. 2005;166:383–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ackerly DD, Donoghue MJ. Am Nat. 1998;152:767–791. doi: 10.1086/286208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davies SJ, Lum SKY, Chan R, Wang LK. Evolution (Lawrence, Kans) 2001;55:1542–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bakker FT, Culham A, Hettiarachi P, Touloumenidou T, Gibby M. Taxon. 2004;53:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donoghue MJ, Baldwin BG, Li JH, Winkworth RC. Syst Bot. 2004;29:188–198. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dilcher DL, Dolph GE. Am J Bot. 1970;57:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Runions A, Fuhrer M, Lane B, Federl P, Rolland-Lagan AG, Prusinkiewicz P. ACM Trans Graphics. 2005;24:702–711. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujita H, Mochizuki A. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2710–2721. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vermeij GJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1804–1809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508724103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwenk K, Wagner GP. In: Phenotypic Integration: Studying the Ecology and Evolution of Complex Phenotypes. Pigliucci M, Preston K, editors. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nelson T, Dengler N. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1121–1135. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Candela H, Martinez-Laborda A, Micol JL. Dev Biol. 1999;205:205–216. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dengler N, Kang J. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:50–56. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horiguchi G, Fujikura U, Ferjani A, Ishikawa N, Tsukaya H. Plant J. 2006;48:638–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sieburth LE. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:1179–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Donoghue MJ. Evolution (Lawrence, Kans) 1989;43:1137–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ehrlich PR, Raven PH. Evolution (Lawrence, Kans) 1964;18:586–608. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thompson JN. The Geographic Mosaic of Coevolution. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harvey PH, Pagel MD. The Comparative Method in Evolutionary Biology. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ackerly DD. Evolution (Lawrence, Kans) 2000;54:1480–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson MC. J Ecol. 1964;52:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maxwell K, Johnson GN. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:659–668. doi: 10.1093/jxb/51.345.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Melcher PJ, Meinzer FC, Yount DE, Goldstein G, Zimmermann U. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:1757–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brodribb TJ, Holbrook NM. New Phytol. 2003;158:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sellin A, Kupper P. Tree Physiol. 2007;27:679–688. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang SD, Tyree MT. J Exp Bot. 1994;45:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thorne ET, Young BM, Young GM, Stevenson JF, Labavitch JM, Matthews MA, Rost TL. Am J Bot. 2006;93:497–504. doi: 10.3732/ajb.93.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 4th Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gilligan CA. Advances in Plant Pathology. London: Academic; 1986. pp. 225–259. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry. 3rd Ed. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.