Abstract

The Neuropsych Questionnaire (NPQ) addresses 2 important clinical issues: how to screen patients for a wide range of neuropsychiatric disorders quickly and efficiently, and how to acquire independent verification of a patient's complaints. The NPQ is available over the Internet in adult and pediatric versions. The adult version of the NPQ consists of 207 simple questions about common symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders. The NPQ scores patient and/or observer responses in terms of 20 symptom clusters: inattention, hyperactivity-impulsivity, learning problems, memory, anxiety, panic, agoraphobia, obsessions and compulsions, social anxiety, depression, mood instability, mania, aggression, psychosis, somatization, fatigue, sleep, suicide, pain, and substance abuse. The NPQ is reliable (patients tested twice, patient-observer pairs, 2 observers) and discriminates patients with different diagnoses. Scores generated by the NPQ correlate reasonably well with commonly used rating scales, and the test is sensitive to the effects of treatment. The NPQ is suitable for initial patient evaluations, and a short form is appropriate for follow-up assessment. The availability of a comprehensive computerized symptom checklist can help to make the day-to-day practice of psychiatry, neurology, and neuropsychology more objective.

Introduction

In prior publications, we have recommended a solution to 2 problems in the clinical practice of psychiatry: that patient evaluation should be more objective and based on more than simply a clinical interview, and that the day-to-day practice of psychiatry should be more procedure-oriented. To these ends, we proposed that computerized neurocognitive testing was potentially useful in the evaluation and management of patients with brain injury,[1] depression,[2] schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,[3] mild cognitive disorder and dementia,[4] and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[5]

Computer technology also has the potential to improve the efficiency of data gathering with respect to patients' subjective complaints. The Neuropsych Questionnaire, which we shall describe, is capable of capturing data that would ordinarily require the administration of several rating scales and symptom checklists. It is a procedure that generates quantitative data about the patient's status at the first evaluation visit and, in a shorter form, at every follow-up visit.

In clinical research, the systematic capture and quantitative analysis of psychiatric symptoms is done by using rating scales and questionnaires (RSs). Conventional RSs are paper-and-pencil jobs that take time to administer and to score. If RSs could be administered electronically, however, clinicians might be inclined to use them more frequently. Capturing systematic and quantitative data about patients' symptoms can have positive ramifications on patient outcome[6] and quality assurance review.[7]

Conventional RSs are inexpensive, quick, and simple to use. Ideally, they capture all of the symptoms or signs of a given condition; if so, they are systematic. The same or similar rating scales can be given to patients and to important others (parents, spouses, teachers, clinicians, etc.), permitting independent or concurrent assessment. Because RSs address key problems, changes in scores are taken to reflect clinically meaningful change; improvement, for example, when the score goes down, deterioration if the score goes up, and “remission” if the score falls below a certain benchmark. Although there are hundreds, if not thousands, of RSs in the medical literature, only a few are widely used. RSs therefore allow for uniformity of assessment and comparability of results in different clinical sites.

Why, then, aren't RSs used more frequently by practitioners? Not because of their conceptual and psychometric weakness, although there is no shortage of those[8]: the problem of rater bias, “halo effects,” “leniency error,” regression to the mean, and the “error of central tendency.” In contrast to medical and psychological tests, RSs are inherently subjective. They are essentially about giving a numerical value to a qualitative state, and they depend on the ability of the informant to understand the question and his inclination to disclose information. Many RSs have a problem with poor correlation between rated and objectively observed behavior.[9] Different RSs have different metrics. A score of 20 indicates mild depression on the Beck Depression Inventory and severe depression on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Twenty is a pathological score on the Conners Parent-Teacher Questionnaire but a normal score on the Brown ADD scales – not that any of this matters much, it seems. In practice, clinicians and investigators simply use their favorite scales, without regard to their psychometric properties.[10]

Of greater concern to practitioners, though, are the practical problems of RSs. A depression RS is appropriate to a clinical trial of patients with depression. But what RS should one use to discover that the patient is depressed in the first place? Comprehensive symptom inventories like the PAI and the BASC and semistructured interviews like the SCID, the SADS, and the MINI are expensive, time-consuming, and hard to score.

Even in areas where RS technology is well developed, like depression, anxiety, and ADHD, different RSs emphasize different aspects of the condition. A good many of the questions on the venerable Hamilton RS for depression are about sleep and anxiety, for example, while the Beck Depression Inventory emphasizes cognitive symptoms of depression. Does that mean one should use both scales?

Because neuropsychiatric patients often have mixed disorders or comorbid disorders, this rationale would lead one to use RSs for the other conditions as well. But to deal with the content validity problem, one would have to use 2 or 3 RSs for every comorbid disorder. That leads to a proliferation of paper that is virtually geometric. Patient response time and clinician scoring time would grow apace. There must be a better way to deal with the disadvantages of RSs than simply multiplying RSs.

The various disadvantages and weaknesses of RSs are outweighed, however, by the importance of being systematic in one's approach to evaluation. Psychiatric RSs may be inherently subjective, but being objective about subjective states is the essence of being a good clinician. So, we developed the Neuropsych Questionnaire to capture the advantages of RS technology and to minimize the inefficiencies and costs of conventional RSs.

Development of the Neuropsych Questionnaire

We developed the Neuropsych Questionnaire for day-to-day use in our clinics. Its purpose is to inquire after the presence and intensity of symptoms of a wide range of neuropsychiatric disorders, to score patient responses and to collect them in the appropriate clinical scales, to generate a report, and to save the results to a central database.

Because the NPQ is administered on a PC, it is a quick test to administer. Two hundred or so questions can be asked and answered in about 15 minutes. Because it is available online, the patient can complete the test at home, prior to his or her visit. Interested parties, spouses, parents, children, teachers, and caregivers can respond to the questionnaire as well, without having to accompany the patient to the office. This generates concurrent data about the patient's condition from the perspective of relevant observers.

The NPQ was not developed as a diagnostic test, any more than any RS is a diagnostic test. It simply presents the opinions of a patient (and others) about the patient's clinical state at a point in time. Therefore, the validity of the questionnaire scores is a matter for the clinician to evaluate. If the NPQ report indicates that the patient scores in the severe range on all of the depression items, for example, that clearly merits the physician's attention. If the scores are low for depression but the patient is clearly depressed during the examination, that also merits attention. It calls attention to patients' appreciation of their problem, or at least their willingness to admit to it. If a patient and spouse generate similar reports, that is reassuring; if their reports are disparate, that also can be useful information.

The NPQ aims to complement the clinical assessment of the neuropsychiatric patient. PC and Internet technology generate quantitative data that enrich the psychiatric interview. The NPQ alleviates the problem of having to inquire arduously after numerous potential problems and allows the clinician to spend more time exploring the meaning of the patient's complaints.

The NPQ was designed to be an initial assessment instrument. As such, asking 200 questions was not inappropriate. The PAI, for example, asks more than 350 questions, and the MMPI more than 500. A long questionnaire, however, is not appropriate for routine follow-up. Analysis of the NPQ, therefore, led to the development of a short form (NPQ-SF), with only 45 questions that can be administered online in about 5 minutes and is suitable for follow-up visits.

Item Selection

The initial selection of items was based on a chart review of presenting symptoms made by patients in their own words. This review yielded a list of 439 symptoms. The list was augmented by a review of a number of RSs and psychological instruments used in the clinics, with special attention to the RS used in clinical trials. They generated 263 symptoms. Eliminating duplication yielded 207 symptom questions in the adult version of the scale and 201 in the pediatric version.

The numbers could be reduced because so many RS items are redundant. Questionnaires about disordered sleep, for example, appear on scales for depression, anxiety, mania, posttraumatic stress disorder, etc. Even with reduction, however, there is 75% concordance between items on the NPQ and items on the RSs listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correspondence Between the NPQ Items and Other RSs

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | 24 | 17 | 0.71 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | 17 | 15 | 0.88 |

| Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale | 10 | 10 | 1.00 |

| Zung Self Rating of Depression Scale | 20 | 16 | 0.80 |

| Davidson Trauma Scale | 17 | 14 | 0.82 |

| ADHD Rating Scale | 18 | 11 | 0.61 |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety | 14 | 12 | 0.86 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 21 | 12 | 0.57 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 21 | 16 | 0.76 |

| Young Mania Rating Scale | 11 | 6 | 0.55 |

| Symptom Checklist - 90 | 90 | 64 | 0.71 |

Item Presentation, Scaling, and Scoring

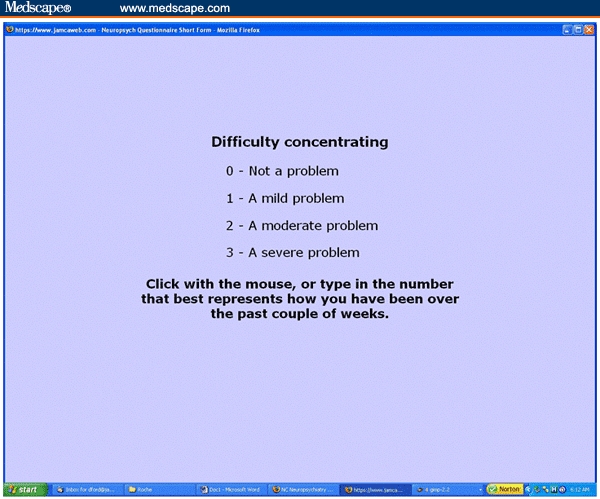

The wording of the items was reduced to the simplest possible terminology, using, whenever possible, words and phrases from patients themselves. The presentation was standardized (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Item presentation.

The symptom, expressed in the simplest possible form, is presented in bold print. The answer grid is always the same: “not a problem,” “a mild problem,” “a moderate problem,” or “a severe problem.” This makes it easy for the subject to respond, and it reduces test time considerably.

Before the questions appear, the subject is instructed on how to answer (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Instructions on how to respond.

The respondent can specify, at the beginning of the test, the time span that is covered by the questionnaire: today, the past few days, the past week, the past couple of weeks, the last month, the past 6 months, the past year, or ever in your life. (The default is “the past couple of weeks.”) The identity of the respondent is also entered at the beginning of the test (patient, husband, wife, son, daughter, mother, father, other relative, friend, caregiver, or teacher) and listed on the report. The questions are posed in a person- and gender specific-way (eg, “Fidgety, I can't sit still,” “Fidgety, he can't…,” or “Fidgety, she can't…”). If the patient is younger than 18 years old, the pediatric questionnaire is administered; those 18 and older take the adult version.

RS technology generally recommends using “anchor points” to describe to the rater where a response should lie, in the most specific terms possible. Anchor points are believed to improve the reliability of an RS. Anchor points would be unwieldy in this format; they would increase reading time. Reliability of the NPQ is achieved through item redundancy.

The optimal number of points on an RS has been the subject of earnest debate; the idea that 7-point scales are optimal dates from 1924,[11] but others have suggested better results with finer-grained scales (10–20 points).[12] Preston and colleagues[13] demonstrated that scales with 7, 8, or 9 points were more reliable than scales with 2, 3, or 4 points. But it has also been represented that “the number of response categories does not materially affect the cognitive structure derived from the results.”[14] Simplicity and ease of administration led us to select a 4-point scale. The idea was that reliability would be preserved by reducing administration time for each item, thus permitting the inclusion of multiple and even redundant items.

Each item is scored as 0–1–2–3. Items are then clustered into scales; all the items that address the specific problem of depression, anxiety, memory, etc., are grouped together. For example, 22 items speak to the problem of memory impairment. The patient's scores on these 22 items are averaged. If the average score is 1.23, it is multiplied by 100 to eliminate the decimal point. So, the patient's memory score would be reported as 123. The highest score someone might receive on a scale is 300; that would indicate that he or she had marked every item in the relevant scale as “a severe problem.” The lowest score one might get is 0; every item in the scale is scored as “not a problem.”

The items in the NPQ are not weighted. That is, every item in a scale is considered as important as every other. This created some anomalies. For example, in the beta version of the NPQ, the item “mind going blank” was deemed as important to the measurement of anxiety as “feeling nervous” or “feeling anxious.” The problem was addressed in the item analysis; items that were infrequently cited by patients, that failed to generate sufficient weight in the factor analysis, or that correlated poorly with the scale score were dropped from that particular scale. In the case of anxiety, “mind going blank” was eliminated but “feeling nervous” and “feeling anxious” were retained.

The test also computes an “average symptom cluster,” which is the average score of all the items on the test. Theoretically, that ought to be a like a global score. It may or may not prove to be a useful metric.

Evaluation of the Beta Version of the NPQ

The NPQ was administered to 814 adults, aged 18–80 years (mean age, 36.6 years; SD 14.1). A total of 45% of the sample were males, and 90% were white. Mean education was 14.5 years. A wide range of neuropsychiatric diagnoses were represented; the numbers in Table 2 add up to more than 814 because many patients had multiple diagnoses.

Table 2.

Diagnoses of the Beta Sample

| DIAGNOSIS | |

|---|---|

| Depression | 210 |

| ADHD | 206 |

| Anxiety | 102 |

| Brain injury | 86 |

| Normal | 80 |

| Bipolar disorder | 75 |

| Anxiety and depression | 29 |

| PTSD | 23 |

| Mild cognitive impairment | 14 |

| Schizophrenia | 10 |

| Chronic fatigue | 5 |

| Conversion disorder | 5 |

| OCD | 4 |

| Social anxiety | 3 |

ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder

The patient diagnoses in the various sections of this paper were conferred by treating clinicians on the basis of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-tr) criteria and were reviewed by the author.

Scale Selection

The items and the scale structure from the beta version of the NPQ were adjusted after data from 814 adult patients were analyzed. The final version of the NPQ includes a number of new, experimental items that were requested by participating clinicians (suicide, pain, substance abuse). The final version of the adult NPQ has 207 questions that represent 20 different symptom clusters, or scales. The pediatric NPQ has 201 questions and 20 scales. The list of 207 items in the adult NPQ and the scales to which they contribute is given in Appendix 1.

The initial selection of scales was based on the frequency of disorders and symptom clusters that present at neuropsychiatry clinics. Factor analysis led to adjustments in the scale structure. Principal component analysis generated a 16-factor solution that accounted for 57% of the variance in the sample. The first factor included depression, anxiety, and mood instability and accounted for 28% of the variance. Discrete factors emerged that defined 10 additional scales: obsessive-compulsive, hyperactive-impulsive, psychotic, mania, somatization, learning problems, panic, social anxiety, aggression, and disordered sleep. Maximum likelihood extraction generated differential factors for panic and agoraphobia.

Discrete factors did not emerge for the scales of attention or fatigue. These scales were deemed clinically important, however, and were retained. Participating clinicians also suggested additional items to add to the NPQ that comprised scales for pain, substance abuse, and suicidality. These were added as experimental scales, subject to future analysis. The 20 scales in the adult NPQ are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Twenty Scales in the Adult NPQ

| BETA VERSION SCALES | FINAL SCALES |

|---|---|

| Inattention | Inattention |

| Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | Hyperactivity-Impulsivity |

| Learning problems | Learning problems |

| Memory problems | Memory problems |

| Anxiety | Anxiety |

| Panic | Panic |

| Agoraphobia | |

| Obsessions, compulsions | Obsessions, compulsions |

| Social anxiety | Social anxiety |

| Depression | Depression |

| Mood instability | Mood instability |

| Mania | Mania |

| Aggression | Aggression |

| Psychosis | Psychosis |

| Somatization | Somatization |

| Fatigue | Fatigue |

| Disordered sleep | Disordered sleep |

| Suicide | |

| Pain | |

| Substance abuse |

The scales refer to symptom clusters and not to DSM or International Classification of Diseases diagnoses. That was a considered decision. The NPQ is a measurement instrument, not a diagnostic instrument. Patients' complaints and the opinions of observers are valuable data, but diagnosis is a medical exercise.

Item Reclassification and Internal Consistency

The internal consistency of each scale was assessed by Cronbach's alpha. The data indicate a high degree of internal consistency for all of the new scales. High alphas (> 0.90) indicate redundancy among the items in several of the scales (Table 4).

Table 4.

Internal Consistency of the Adult NPQ Scales

| Cronbach's alpha N= 814 | ||

|---|---|---|

| alpha | ||

| ATT | Inattention | 0.911 |

| HA-IMP | Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | 0.826 |

| LPX | Learning problems | 0.895 |

| MEM | Memory problems | 0.942 |

| ANX | Anxiety | 0.92 |

| PANIC | Panic | 0.866 |

| AGORA | Agoraphobia | 0.87 |

| OCD | Obsessions, compulsions | 0.915 |

| SAD | Social anxiety | 0.882 |

| DEP | Depression | 0.95 |

| MS | Mood instability | 0.925 |

| MANIA | Mania | 0.788 |

| AGG | Aggression | 0.884 |

| PSYCHO | Psychosis | 0.838 |

| SOM | Somatization | 0.938 |

| FATIG | Fatigue | 0.918 |

| SLEEP | Disordered sleep | 0.856 |

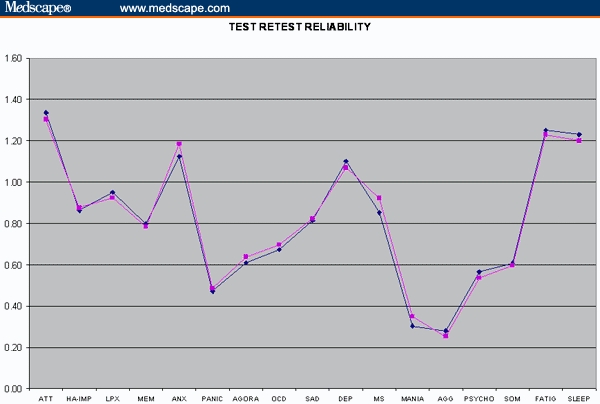

Test-Retest Reliability: Patients Tested Twice

Seventy-five neuropsychiatric patients were administered the NPQ on 2 occasions within 3 months. The diagnoses were mixed (depression, 16; brain injury, 10; bipolar disorder, 9; anxiety, 8; chronic pain, 5; ADHD, 4; PTSD, 4; mild cognitive impairment or early dementia, 3; schizophrenia, 2; and mixed disorders accounting for the rest). Mean age was 42.4 years (range, 18–72) and mean years of education was 14.3 years (range, 10–18). Forty-four participants were female, and 67 were white (Table 5; Figure 3).

Table 5.

Test-Retest Reliability for Patients Taking the Adult NPQ

| Patient-Patient N = 75 | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | P < | |

| ATTENTION | 0.70 | 0.00000 |

| HA-IMP | 0.66 | 0.00000 |

| LPX | 0.80 | 0.00000 |

| MEM | 0.74 | 0.00000 |

| ANX | 0.73 | 0.00000 |

| PANIC | 0.67 | 0.00000 |

| AGORA | 0.77 | 0.00000 |

| OCD | 0.88 | 0.00000 |

| SAD | 0.77 | 0.00000 |

| DEP | 0.80 | 0.00000 |

| MS | 0.76 | 0.00000 |

| MANIA | 0.59 | 0.00000 |

| AGG | 0.70 | 0.00000 |

| PSYCHO | 0.80 | 0.00000 |

| SOM | 0.77 | 0.00000 |

| FATIG | 0.72 | 0.00000 |

| SLEEP | 0.54 | 0.00000 |

| ASC | 0.85 | 0.00000 |

| average | 0.74 | |

| min | 0.54 | |

| max | 0.88 | |

Figure 3.

NPQ scores on 2 successive administrations.

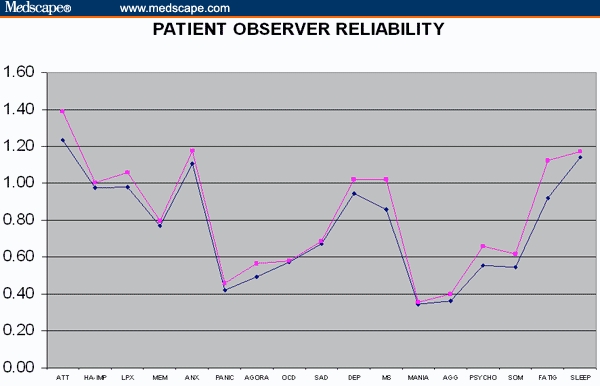

Interrater Reliability: Patient-Observer Pairs

Eighty-two neuropsychiatric patients and their closest relation were administered the NPQ on the same day, but separately, in 2 separate rooms. The diagnoses were mixed (depression, 15; brain injury, 17; bipolar disorder, 4; chronic pain, 4; ADHD, 3; PTSD, 2; mild cognitive impairment or early dementia, 1; schizophrenia, 1; mild mental retardation, 3; and mixed disorders accounting for the rest). Mean age was 38.2 years (range, 18–68) and mean years of education was 14.2 (range, 8–20). Twenty-five were female, and 71 were white (Table 6; Figure 4).

Table 6.

Interrater Reliability, Patient-Observer Pairs

| Patient-Observer N = 82 | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | P < | |

| ATTENTION | 0.39 | 0.00032 |

| HA-IMP | 0.63 | 0.00000 |

| LPX | 0.34 | 0.00171 |

| MEM | 0.49 | 0.00000 |

| ANX | 0.62 | 0.00000 |

| PANIC | 0.63 | 0.00000 |

| AGORA | 0.63 | 0.00000 |

| OCD | 0.51 | 0.00000 |

| SAD | 0.59 | 0.00000 |

| DEP | 0.57 | 0.00000 |

| MS | 0.56 | 0.00000 |

| MANIA | 0.34 | 0.00158 |

| AGG | 0.58 | 0.00000 |

| PSYCHO | 0.60 | 0.00000 |

| SOM | 0.74 | 0.00000 |

| FATIG | 0.54 | 0.00000 |

| SLEEP | 0.43 | 0.00005 |

| ASC | 0.62 | 0.00000 |

| average | 0.54 | |

| min | 0.34 | |

| max | 0.74 | |

Figure 4.

NPQ scores, patients and observers.

Sensitivity to Treatment

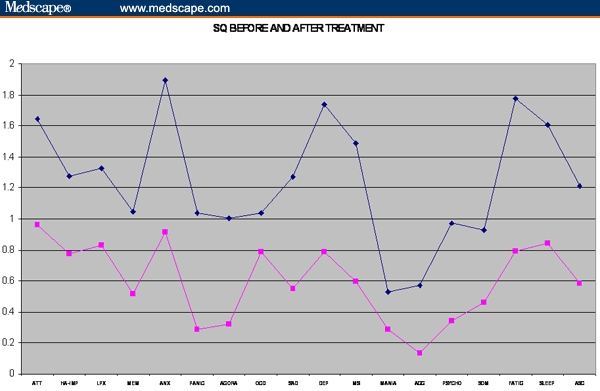

Twenty-four patients with various neuropsychiatric disorders were administered the NPQ on 2 occasions, once prior to treatment, and then after treatment. Mean patient age was 36.3 years (range, 20–55) and mean years of education was 14.3 (range, 8–20). Fourteen patients were female and 22 were white. Diagnoses included depression (6), bipolar affective disorder (5), ADHD (4), anxiety (2), obsessive-compulsive disorder (2), PTSD (2) and brain injury (2) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

NPQ before and after treatment.

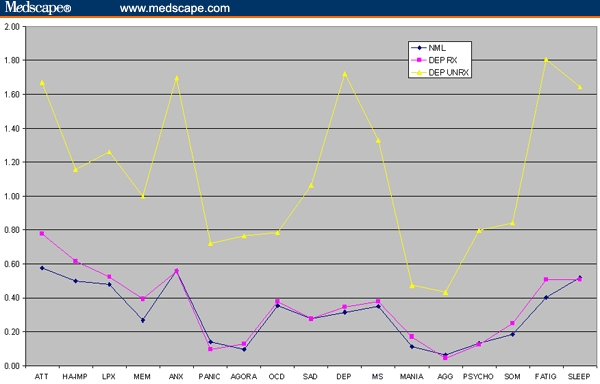

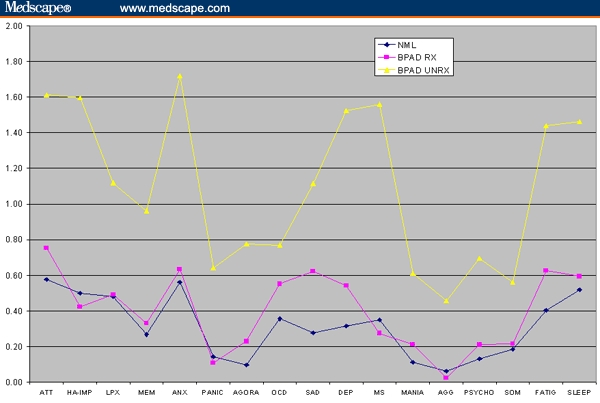

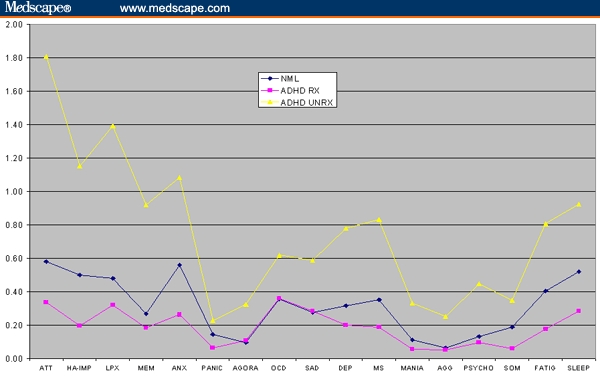

The NPQ in Different Diagnostic Groups

NPQ results were available for 809 neuropsychiatric patients, with reliable data on diagnosis and treatment response. After independent chart review, the following records were selected (Figures 6–9). The remaining patients had mixed or ambiguous diagnoses. The patients were divided into 2 groups: new patients who had not yet been treated, and patients whose treatment was deemed successful by the treating physician. Partial responders, or patients whose treatment was not yet completed, were excluded. The figures also include data from 80 normal controls.

Figure 6.

170 patients with depression, 112 pretreatment, 58 treated successfully.

Figure 9.

58 patients with bipolar disorder, 26 pretreatment, 32 treated successfully.

The Short Form of the Neuropsych Questionnaire (NPQ-SF)

The NPQ only takes 15 minutes, but a shorter questionnaire would be more appropriate for follow-up visits. The fact that many of the items in the NPQ are redundant made it relatively easy to develop a shorter form of the questionnaire. The goal was to cover the most important scales in a questionnaire that contained 45 items and could be administered in less than 5 minutes.

The process of item selection was based on factor loadings, intercorrelation analysis, and symptom frequency in patients with known disorders. Several scales from the NPQ were not used in the short form. This was largely a clinical decision. “Learning problems” is a scale more pertinent to a diagnostic evaluation than to follow up. The clinical problem of agoraphobia is not commonly met within our patient population. Patients with social anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and bipolar affective disorder seem to be less forthcoming about their core symptoms and more likely to complain of problems with attention, fatigue, anxiety, etc.

The scale scores for the NPQ-SF are highly correlated with the NPQ scale scores (r 0.89–0.99) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlation Between the NPQ and the NPQ-Short Form

| SHORTFORMS | ATT | HA-IMP | MEM | ANX | PANIC | DEP | MS | AGG | SOM | FATIG | SLEEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASC | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.62 |

| ATT-SF | 0.96 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| HA-SF | 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

| MEM-SF | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| ANX-SF | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.99 | 0.66 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.73 |

| PANC-SF | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.70 | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| DEP-SF | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.95 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.72 |

| MS-SF | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.52 |

| AGG-SF | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.29 |

| SOM-SF | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.56 |

| FTG-SF | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.51 |

| SLEEP-SF | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.94 |

The reliability of the NPQ-SF is almost as good as the NPQ (Table 8). Test-retest reliability for the NPQ ranges from 0.54–0.80, average 0.71; for the NPQ-SF, 0.53–0.82. Interrater reliability for the NPQ, patient-observer pairs is 0.39–0.74.

Table 8.

Comparative Reliability of the NPQ and the NPQ-SF

| NPQ | Patient-Patient N = 75 | Patient-Observer N = 82 | Two observers N =28 |

|---|---|---|---|

| average | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.61 |

| min | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.42 |

| max | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.81 |

| NPQ-SF | |||

| average | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.54 |

| min | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.33 |

| max | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

The advantage of a longer questionnaire is that it is more reliable, but in this case, it is not much more reliable. Why not use the short form all the time, then? Clinicians can choose to do as they please, but we prefer the NPQ for evaluations and re-evaluations, and the short form for follow-ups. The NPQ is much more comprehensive, and even though patients with some disorders may not be forthcoming or insightful concerning their symptoms, their close relations are likely to be more accurate in their assessments.

Availability of the NPQ

The NPQ and the NPQ-SF are available without charge to qualified psychiatrists, neurologists, and psychologists through our Web site (see Box). All one needs is a PC and a high-speed Internet connection. The program works best on Mozilla, a free internet browser. A report is generated as soon as the test is completed. At some point, we hope that practitioners will be able to store the data they generate in a central storage facility, as we do, and that the program will be able to generate serial data. For now, though, the only record is the hard copy report one prints out when the test is done.

Accessing the Neuropsych Questionnaire

http://www.ncneuropsych.com > Online Assessment > Start Online Assessment Administrator Name: doctor Password: doctor

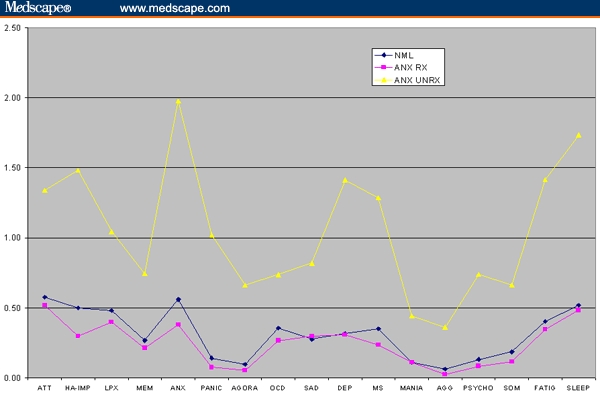

Figure 7.

153 patients with ADHD, 113 pretreatment, 40 treated successfully.

Figure 8.

78 patients with anxiety, 49 pretreatment, 29 treated successfully.

Acknowledgments

The Neuropsych Questionnaire and related instruments were developed at The North Carolina Neuropsychiatry Clinics in Chapel Hill and Charlotte by Dr. Gualtieri.

Funding Information

This research was supported by North Carolina Neuropsychiatry, PA, in Chapel Hill and Charlotte. No external support was sought or received on behalf of this research.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: An Internet-Based Symptom Questionnaire That Is Reliable, Valid, and Available to Psychiatrists, Neurologists, and Psychologists See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at tg@ncneuropsych.com or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

References

- 1.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG, Benedict KB. Psychometric and clinical properties of a new computerized neurocognitive screening battery. Program and abstracts of the ANPA Annual Meeting; February 24–25, 2004; Bal Harbor, Florida. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG, Benedict KB. Neurocognition in depression: patients on and off medication, compared to normal controls. J Neuropsych Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:217–225. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG. A computerized neurocognitive test battery for studies of schizophrenic and bipolar patients. Schiz Res. 2006;81:122. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG. Neurocognitive testing supports a broader concept of mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;20:359–366. doi: 10.1177/153331750502000607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG. Efficient allocation of attentional resources in patients with ADHD: maturational changes from age 10 to 29. J Attention Dis. 2006;9:534–542. doi: 10.1177/1087054705283758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slade M, McCrone P, Kuipers E, et al. The use of standardized outcome measures in adult mental health services: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:330–336. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesselheim AS, Ferris TG, Studdert DM. Will physician-level measures of clinical performance be used in medical malpractice litigation? JAMA. 2006;15:1831–1834. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? Am J Psychiatry. 2004;61:2163–2177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. Second Edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mowbray RM. Psychometrics & psychopharmacology. In: Burrows GD, Werry JS, editors. Advances in Human Psychopharmacology. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press; 1981. pp. 129–182. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symonds PM. On the loss of reliability in ratings due to the coarseness of the scale. J Exp Psychol. 1924;17:456–461. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garner WR. Rating scales, discriminability, and information transmission. Psychol Rev. 1960;67:343–352. doi: 10.1037/h0043047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preston CC, Colman AM. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2000;104:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0001-6918(99)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schutz HG, Rucker MH. Variable configurations across scale lengths: an empirical study. Educ Psychol Measurement. 1975;35:319–324. [Google Scholar]