Abstract

Context

MySpace is a popular social networking Web site where users create individual Web profiles. Little data are available about what types of health risk behaviors adolescents display on MySpace profiles. There are potential risks and intervention opportunities associated with posting such information on a public Web site.

Objective

To examine publicly available 16- and 17-year-old MySpace Web profiles and determine the prevalence of personal risk behavior descriptions and identifiable information.

Design

Cross-sectional observational study using content analysis of Web profiles.

Setting

Patients

In order to target frequently visited adolescent Web profiles, we sequentially selected 142 publicly available Web profiles of 16 and 17 year olds from the class of 2008 MySpace group.

Interventions

None.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of displayed health risk behaviors pertaining to substance use or sexual behavior, prevalence of personally identifying information, date of last log-in to Web profile.

Results

Of Web profiles, 47% contained risk behavior information: Twenty-one percent described sexual activity; 25% described alcohol use; 9% described cigarette use; and 6% described drug use. 97.2% Contained personally identifying information: Seventy-four percent included an identifiable picture; 75% included subjects' first names or surnames; and 78% included subjects' hometowns. Eighty-six percent of users had visited their own profiles within 24 hours.

Conclusions

Most 16- and 17-year-old MySpace profiles include identifiable information, are frequently accessed by owners, and half include personal risk behavior information. Further study is needed to assess the risks associated with displaying personal information and to evaluate the use of social networking sites for health behavior interventions targeting at-risk teens.

Introduction

Social networking sites, such as MySpace and Facebook, have become popular Internet venues for adolescent social interaction. Approximately 25% of the estimated 150–160 million users of MySpace, the largest site, are under age 18.[1] Social networking Web sites allow users to create personal profiles, communicate with others, and join groups. Given that the adolescent developmental stage prioritizes peer relationships and identity exploration, the immense popularity of MySpace among adolescents may bring little surprise. Personal Web profiles are multimedia creations featuring text, pictures, blogs, audio, and video all posted by the profile owner to represent his or her identity. Web profiles may be public and available to anyone on the Internet, or private and available only to those who the profile owner designates as “friends.”

Recent media reports have highlighted cases in which young adults posted information about risk behaviors, such as sexual activity and substance use, on their publicly accessible Web profiles and experienced repercussions of these disclosures.[2–4] It is worth noting that posting risk behavior information on a public Web profile may place adolescents at risk, regardless of whether or not that information is valid. These risks may include unwanted contact and adverse reactions from potential employers, school admissions officers, and others. Another risk is that displaying risk behavior information on Web profiles normalizes risky behavior within the adolescent cohort and may encourage peers to engage in risky behavior themselves. The goal of this study was to determine how common such health risk behavior disclosures were in the public MySpace profiles of adolescents who actively use MySpace. We also assessed the prevalence of display of personally identifying information, such as name, picture, and hometown. Posting both identifiable and risk behavior information creates additional risks to adolescents, as individuals may be targeted on the basis of the display of risk behavior information, then easily identified and located.

Methods

Subjects

Our target population was adolescents aged 16 and 17 who maintained a MySpace personal Web profile. MySpace allows teens age 14 and over to create and maintain Web profiles. At the time of our study, teens aged 14 and 15 were required to have their profile security set to “private,” enabling the profile owner to give permission in order to view the profile. All other profile owners age 16 and up may choose to set their profile security to public or private. We chose 16 and 17 year olds in order to focus on teens under 18 whose MySpace profiles could be publicly available. We wanted to target adolescents who were personally invested in this Web site; therefore, we focused on adolescent subjects who belonged to at least 1 MySpace group in addition to having a personal Web profile. We selected the “class of 2008 group” because it was publicly available, had open membership, was popular among teens (approximately 11,000 members at the time of the study), contained subjects in our target age range of 16 and 17, and was not focused on a particular interest (such as a sports-related group). Subjects were included in this study if they made their profiles publicly viewable, were a member of the class of 2008 group, reported their home location as in the United States, and reported their age as 16 or 17.

Data Collection

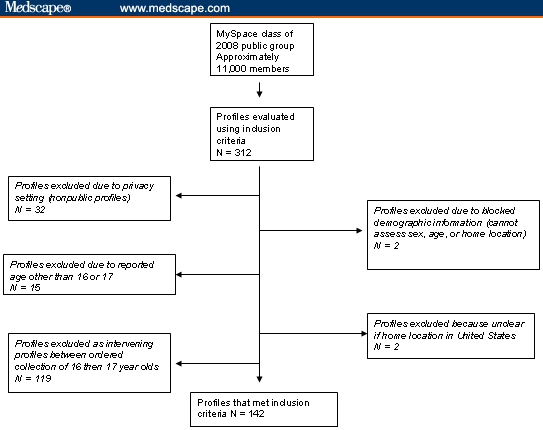

Profiles in the MySpace class of 2008 group were listed in nonalphabetic nonnumeric order on the Web site. A pilot analysis of this group revealed that profiles were generally listed within this group in order of the most recent date that the profile owner has logged into their own profile. We were interested in evaluating profiles that were actively maintained by users. Therefore, we decided to evaluate profiles sequentially in order to focus on profiles with a more recent date of log-in. In order to achieve equal numbers of 16 and 17 year olds, profiles that met the inclusion criteria were accepted into the study in alternating order of 16 year old then 17 year old, with intervening profiles dropped (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subject selection.

The principal investigator (PI) reviewed all elements of the MySpace profile that were publicly viewable, including pictures, blog entries, and public comments left by other visitors. No attempts were made to contact any subjects or to obtain access to information set as “private.” We recorded commonly given background information, including age, sex, home state, and most recent date of log-in. In addition, a record was made in regard to whether subjects had given their personal names, provided pictures of themselves, or identified their ethnicity.

In order to assess the display of risk behaviors of sexual activity or substance use, we reviewed a pilot sample of approximately 20 profiles to determine commonly found keywords and displayed imagery. Examples of references to sexual behavior included listing sex as a hobby; displaying pictures of oneself wearing only undergarments; or displaying downloaded icons with sexual imagery, such as a “great piece of ass” certificate. Examples of references to substance use included listing substance use as a hobby; displaying pictures of oneself drinking a beer or smoking; or displaying downloaded icons with imagery, such as beer brands or marijuana leaves. References to sexual behavior and substance use were counted only if they were unambiguous and clearly referred to the subject. Any ambiguous data points in regard to health risk behavior displays were discussed with another researcher, and only items on which there was consensus were included.

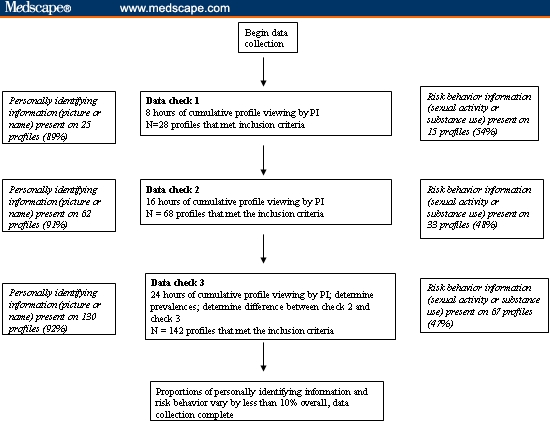

Because this study was exploratory and descriptive, we established a data checkpoint system to assess when data collection was complete. Because our goal was to determine the prevalence of personally identifying information and risk behavior information, our strategy was to collect data until we determined that these prevalences were stable despite the addition of any additional data. Several data checkpoints that were based on cumulative time-viewing profiles were determined prior to the study. These data checkpoints were established at 8, 16, and 24 hours of cumulative viewing of profiles by the PI. At each data checkpoint, the overall prevalence of risk behaviors and personally identifying information was determined. We determined that once both prevalences remained unchanged (varying by 10% or less) for 2 data checks in a row, data collection was considered complete. Please see Figure 2 for a detailed description of our data checkpoint system.

Figure 2.

Data collection process.

Results

The 142 surveyed Web profile owners came from 35 states and were 53% girls and 47% boys. Among those who identified a race or ethnicity (n = 119), 55% were white; 16% were Asian; 15% were African-American; 11% were Hispanic; and 3% were East Indian.

Most Recent Log-in to Own Profile

Eighty-six percent of profile owners had logged in within the previous 24 hours, whereas an additional 6.3% had logged in within the previous week. Most of the remaining subjects had logged in within the past month (2.8%) or the past 3 months (1.4%). Log-in dates could not be determined for 3.5%.

Information Enabling Personal Identification

Seventy-four percent of profiles (n = 105) included a picture that clearly identified the profile owner, whereas 23% (n = 33) included a nonidentifiable photograph (group photo or unidentifiable solo photo). Only 4 profiles did not include a photograph. First names of profile owners were included on 75% of the profiles, and 17.6% included both first names and surnames. Hometown and state were included on 78% of profiles.

Risk Behavior Information

Almost half (47%) of Web profiles contained at least 1 public disclosure of sexual activity or substance use. Of the Web profiles that displayed risk behavior information, the majority displayed 1 risk behavior (43%), although some displayed 2 risk behaviors (16%) and a minority displayed 3 or more risk behaviors (7%). The most common displayed risk behavior was alcohol use (25%), but many also disclosed drug and tobacco use (Table 1). References to sexual activity were included in 21% of the profiles. Examples of sexual references found in these data are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Posted Risk Behavior Information on 16 and 17 Year Olds' Publicly Available MySpace Web Profiles

| Posted Risk Behaviors | Total Number of Sites Referencing Activity | Sites Referencing Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual activity | 31 | 21% |

| Alcohol use | 36 | 25% |

| Drug use | 9 | 6% |

| Cigarette use | 13 | 9% |

| Total number of sites | 142 |

Table 2.

Sample Web Site Entries of 16- and 17-Year-Old MySpace Profile Owners That Suggest Sexual Activity, by Category

| Category | Examples From Web Profiles | |

|---|---|---|

| References sex in response to quiz or survey | Downloads quiz onto Web site – “what kind of sex should you have” – and fills out answers | Downloads quiz onto Web site containing the question: “Who was the last person to sleep in your bed?” Writes in answer name of previous partner |

| Lists sex as hobby or interest | Lists hobbies – “doing girls” | Lists hobbies: “My interests are boys, sex, and alcohol.” |

| Discusses sex in the context of past or present relationship | Writes about first sexual experience with previous boyfriend | Describes “best time” as sexual experience with boyfriend |

| Links personal identity with sex | Refers to self on profile as having had an STD | Describes self as a “whore” |

STD = sexually transmitted disease

Discussion

Internet venues, such as MySpace, allow adolescents to experiment with self-expression and engage in identity play to a degree never before possible.[5] We found that adolescents often publicly disclosed risk behaviors in ways that created still further risk. Nearly half of the adolescents we sampled publicly disclosed sexual activity, alcohol use, tobacco use, or drug use. Many disclosures were surprisingly explicit. Such disclosures put adolescents at risk in at least 3 ways that exist regardless or whether the disclosed information is valid. First, disclosures of sexual behavior and substance use may attract unwanted sexual solicitation. Evidence suggests that 10% to 20% of adolescents online are subjects to such solicitation; it is reasonable to suspect that teens who display sexually suggestive material on profiles may be at higher risk.[6] Second, displaying risk behavior information on the Internet may adversely affect adolescents' future employment or college opportunities. Although a systematic assessment has yet to be made, there are reports of businesses and universities using social networking profiles in decisions in regard to potential employees and students.[2–4] Teens in our study also frequently displayed information that would allow them to be identified; the majority displayed pictures and first names and nearly 20% listed both their full names. Finally, displaying risk behavior information on Web profiles may affect other teens by normalizing risky behavior within the adolescent cohort.

However, the results of this study also point to how social networking sites, such as MySpace, may be used for targeted interventions by health educators and providers. Adolescents are generally a healthy population, with most health risks stemming from health risk behaviors.[7–18] Adolescents are also among the least likely population to visit the physician: Studies have suggested that adolescents with either low socioeconomic status or involvement in risk behaviors are particularly unlikely to seek medical care.[19,20] For adolescents who do visit the doctor, many are not asked about risk-taking behaviors, such as substance use and sexual activity.[21,22] It is clear that innovative approaches must be taken in order to identify teens considering or engaging in risk-taking behaviors, and to provide both prevention and intervention efforts. The Internet, and social networking Web sites in particular, may provide a new venue for identification of teens at risk for health behavior consequences, and an avenue in which to communicate with these adolescents.

Our results demonstrate that several important risk factors can be identified effectively and efficiently using publicly available Web profiles. Some sites also feature internal search engines that allow rapid identification of profiles displaying risk behavior. On MySpace, for example, it is possible to search for users who self-identify as drinkers and smokers. Further, social networking Web sites typically allow direct access to a large number of adolescents through email. Educators and providers may also create or work through one of the thousands of groups devoted to health topics on MySpace. Previous studies have demonstrated that Internet approaches to modify behavior can be effective in older populations.[23–25] Social networking sites may provide a new venue for identification, assessment, and interventions to prevent or reduce health risks.

An important factor to consider when viewing information posted on MySpace is that social networking Web sites provide no verification of any information displayed on individuals' Web profiles. The validity of online personal risk behavior information has not been completely evaluated, but there are reasons to be concerned that such disclosures reflect either intent or actual behaviors. Previous studies of Internet behaviors have shown that computer use often encourages self-disclosure and “hyperpersonal” information, which supports the validity of Internet self-report.[26,27] Most teens reported that the majority of their online self-representation reflects their identity, but the presentation may not be entirely current.[28–30] Previous studies have also shown that even on Web sites designed to promote identity experimentation and exploration, such as chat rooms, subjects generally evolved their online presentations to fit their own identities.[31] The Media Practice Model summarizes these findings by stating that adolescents choose and interact with media on the basis of who they are, or who they want to be, at the moment.[32] This theory suggests that adolescent disclosures made on MySpace profiles reflect either actual behaviors or behavioral intent, both of which are of interest to healthcare providers, educators, and parents.

Before additional steps can be taken toward healthcare interventions on social networking Web sites, more research is clearly needed to assess the validity of online displays of personal information, adolescents' willingness to interact with adults on social networking Web sites, and how to best use the multimedia resources that these Web sites offer.

Limitations to this study include that, as described above, information displayed by profile owners, including ages, pictures, and behavioral descriptions, cannot be objectively verified. In particular, anecdotal reports suggest that teens frequently misrepresent their age on Web profiles in order to bypass security restrictions placed on the profiles of younger teens. We studied profiles within the class of 2008 group in an effort to improve the likelihood of viewing profiles of actual 16- and 17-year-old adolescents. However, targeting 16 and 17 year olds through this MySpace group biased our sample population to adolescents in school and who join online groups, limiting generalizability. Finally, although our prevalences were stable between data checkpoints, this study conducted a detailed evaluation of a relatively small number of profiles compared with the total 11,000 available for the class of 2008 group. The results of this study nonetheless indicate that adolescents who are active users of MySpace regularly post health risk behaviors and display personal identification.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dimitri Christakis, MD, MPH, for his assistance with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: What Are Adolescents Showing the World About Their Health Risk Behaviors on MySpace? See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at megan.moreno@seattlechildrens.org or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Megan A. Moreno, University of Washington, Seattle Author's email: megan.moreno@seattlechildrens.org.

Malcolm Parks, Communication, University of Washington, Seattle.

Laura P. Richardson, Adolescent Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle.

References

- 1.Bausch S, Han L. Social networking sites grown at 47 percent, year over year, reaching 45 percent of Web users, according to Nielsen/NetRatings. 2006 Available at: http://www.nielsen-netratings.com/pr/pr_060511.pdf Accessed October 2, 2007.

- 2.Finder A. For some, online personal undermines a resume. New York Times. June 11, 2006.

- 3.Doyle A. To blog or not to blog? How blogging and social networking websites can impact your job search. May 2007. About: Job Searching. Available at: http://jobsearch.about.com/od/jobsearchblogs/a/jobsearchblog.htm Accessed October 2, 2007.

- 4.Hanisko H. MySpace is public space when it comes to job search. 2006 CollegeGrad.com. Available at: http://www.collegegrad.com/press/myspace.shtml Accessed October 2, 2007.

- 5.Walther JB, Parks MR. Cues filtered out, cues filtered in: computer mediated communication and relationships. In: Knapp ML, Daly JA, Miller GR, editors. The Handbook of Interpersonal Communication. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2002. pp. 529–563. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolak J, Finkelhor D, Mitchell K. Internet-initiated sex crimes against minors: implications for prevention based on findings from a national study. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:424, e11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arata CM, Stafford J, Tims MS. High school drinking and its consequences. Adolescence. 2003;38:567–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett R, Holditch-Davis D, Belyea M. Problem behaviors in adolescents. Pediatr Nurs. 2007;33:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NIH, National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Tobacco use: prevention, cessation and control. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:839–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. The co-occurrence of substance use and high-risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:609–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busen NH, Marcus MT, von Sternberg KL. What African-American middle school youth report about risk-taking behaviors. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camenga DR, Klein JD, Roy JR. The changing risk profile of the American adolescent smoker: implications for prevention programs and tobacco interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:120, e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Bryant FB, King S. Does substance use moderate the effects of parents and peers on risky sexual behaviour? AIDS Care. 2006;18:194–200. doi: 10.1080/09540120500456391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez JP, Bertozzi SM, Conde-Glez CJ, Sanchez-Aleman MA. Risk behaviors of 15–21 year olds in Mexico lead to a high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections: results of a survey in disadvantaged urban areas. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommers I, Baskin D, Baskin-Sommers D. Methamphetamine use among young adults: health and social consequences. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H, Li X, Barth-Jones DC. Age of sexual initiation and HIV-related behaviours: application of survival analysis. Sex Health. 2006;3:57–58. doi: 10.1071/sh05049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehrer JA, Pantrell R, Tebb K, Shafer MA. Forgone health care among U.S. adolescents: associations between risk characteristics and confidentiality concern. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKee D, Fletcher J. Primary care for urban adolescent girls from ethnically diverse populations: foregone care and access to confidential care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17:759–774. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halpern-Felsher BL, Ozer EM, Millstein SG, et al. Preventive services in a health maintenance organization: how well do pediatricians screen and educate adolescent patients? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:173–179. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellen JM, Franzgrote M, Irwin CE, Jr, Millstein SG. Primary care physician's screening of adolescent patients: a survey of California physicians. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:433–438. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, Rivara FP, Ebel B. Improving pediatric prevention via the Internet: a randomized, controlled trail. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1157–1166. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A controlled trial of Web-based feedback for heavy drinking college students. Prev Sci. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klausner JD, Levine DK, Kent CK. Internet-based site-specific interventions for syphilis prevention among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care. 2004;16:964–970. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace P. Psychology of the Internet. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming PJ. Software and sympathy: therapeutic interaction with the computer. In: Fish SL, editor. Talking to Strangers: Mediated Therapeutic Communication. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenhart A, Madden M. Teens, privacy and online social networks: how teens manage their online identities and personal information in the age of MySpace. Pew Internet & American Life Project. 2007 Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/211/report_display.asp Accessed October 2, 2007.

- 29.Klein JD, Graffle Havens C, Thomas RS, Wanja K, Morris G. The impact of cyberspace on teen and young adult social networks. Poster and abstracts of the Pediatric Academic Societies' (PAS) 2007 Annual Meeting; May 5–8, 2007; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caspi A, Gorsky P. Online deception: prevalence, motivation, and emotion. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:54–59. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bechar-Israeli H. From “Bonehead” to “cLoNehEAd”: nicknames, play, and identity on Internet relay chat. J Computer Mediated Commun. 1996;1 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown JD. Adolescents' sexual media diets. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(suppl):35–40. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]