Abstract

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), committed to by all 191 United Nations member states, are rooted in the concept of sustainable development. Although 2007 (midway) reports indicated that programs are under way, unfortunately many countries are unlikely to reach their goals by 2015 due to high levels of poverty. Madagascar is one such example, although some gains are being made. Attempts of this island nation to achieve its MDGs, expressed most recently in the form of a Madagascar Action Plan, are notable in their emphasis on (1) conserving the country's natural resource base, (2) the effect of demographic trends on development, and (3) the importance of health as a prerequisite for development. Leadership in the country's struggle for economic growth comes from the president of the Republic, in part, through his “Madagascar Naturally” vision as well as his commitment to universal access to family planning, among other health and development interventions. However, for resource-limited countries, such as Madagascar, to get or stay “on track” to achieving the MDGs will require support from many sides. “Madagascar cannot do it alone and should not do it alone.” This position is inherent in the eighth MDG: “Develop a global partnership for development.” Apparently, it takes a village after all – a global one.

World's fourth largest island

Total area – 226,656 square miles

Surface area protected (as of 2006) – 3%

Population size (as of 2006) – 18,595,469

Population density (population/square mile) – 78

Life expectancy at birth (both sexes) – 78 years

Natural growth rate – 2.7%

Population living below $2/day – 85%

Source: Population Reference Bureau (PRB) 2006 World Population Data Sheet. Available at: www.prb.org/pdf06/06WorldDataSheet.pdf (Figure)

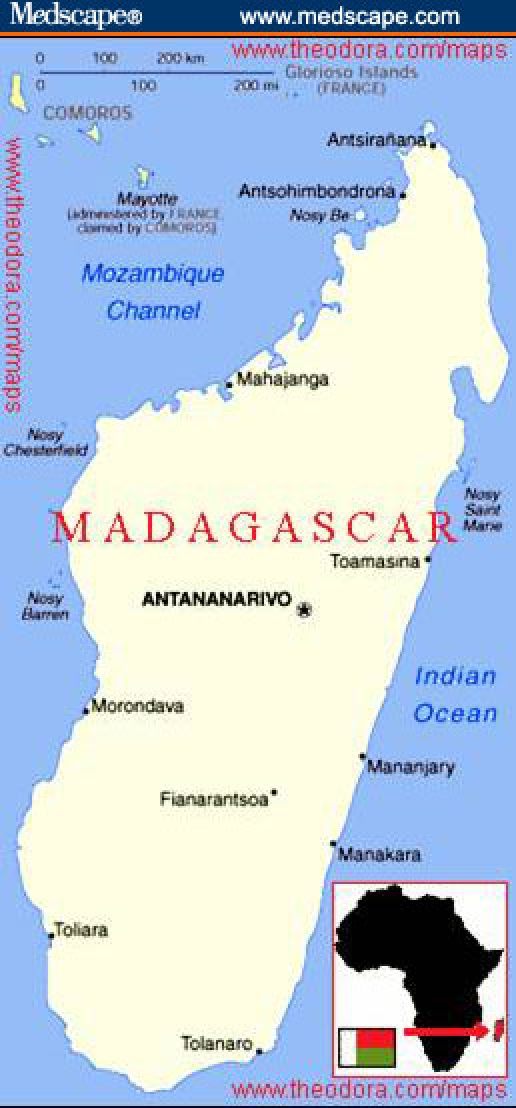

Figure.

Madagascar

Source: www.theodora.com/maps

United Nations Commitment to Poverty Reduction Through Sustainable Development

At the turn of the century, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly – the largest gathering of world leaders, all 191 UN member states – developed a Millennium Declaration pledging a “new global partnership to reduce extreme poverty.[1]” The 22nd resolution of this declaration reaffirmed the Declaration on Environment and Development, established during the 1992 UN meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, known as Agenda 21. The latter, an action plan, called for ways to achieve sustainable economic development of resource-limited countries, through attention to natural resource management.[2] (Sustainable development was defined in a 1987 UN meeting as “development that helps populations meet current needs while at the same time not compromising the ability of future generations to meet their basic needs.”) Eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were also developed as part of the Millennium Declaration, pledged by all 191 nations, to be reached by 2015.[3] These MDGs are all deeply rooted in the concept of sustainable development (see Appendix).

Progress Toward the MDGs

Since 2000, when the MDGs were first announced, developing country governments – aided by local and international development agencies – have launched a number of initiatives focusing on 1 or more of the 8 goals. A halfway (2007) report on progress toward the MDGs revealed that, although programs have been implemented to achieve the goals, it is not apparent that they will be successfully reached by 2015.[4] Despite notable gains made in several areas, in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, given high levels of extreme poverty, the Continent is not considered on track to achieving any of the goals by 2015.[5]

Madagascar, the biodiversity-rich island nation off the coast of East Africa, is an example of one country making some positive progress toward reaching the MDGs, particularly in the areas of education and nutrition.[6] Progress on the health-related MDGs is also believed to be encouraging. Nevertheless, Madagascar is unlikely to reach most of the MDGs, if current trends continue.[6] While falling short of midway target levels, attempts of Madagascar toward achieving the MDGs are, nonetheless, notable for a variety of reasons, including:

An emphasis on conserving the country's natural resource base, including its unique biodiversity;

Acknowledgment of the effect of demographic trends on development and the environment (emphasized at the International Conference on Population and Development, in 1994, in Cairo, Egypt)[7];

Appreciation of the importance of health as a requirement for development; and

The visible leadership of the president of the republic.

Focus on Madagascar

Madagascar is one of the poorest countries in the world. In 2006, her human development index rank was 149 out of 177.[8] Seventy percent of the country's 18+ million citizens (18,595,469, July 2006 estimate - https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/print/ma.html) live below the poverty line of $1 per day; 80% live on less than $2 per day; and proportions are higher in the rural areas, where over 75% of the population lives.[9–11] Madagascar also continues to face serious health problems. Acute respiratory infection, diarrhea diseases, fever, and high levels of acute and chronic malnutrition in children under 3 years of age exemplify the country's disease burden. Over 40% of children are characterized as underweight, and many also suffer from iodine and vitamin A deficiencies that affect immune function and health outcomes in later years.[12]

Agriculture is the basis of the rural economy, giving it a lead role in overall national development. To productively work in the fields, however, people must be healthy. Time away from work in the fields, to take care of sick family members or to transport them to health facilities distant from their communities, is income lost. For subsistence farmers, who comprise a substantial proportion of the rural poor, time and money spent on health problems jeopardize the already tenuous levels of household and community food security. For many rural Malagasy, crop yields are significantly lower than their theoretical potential (15% of the potential for rice).[13] Therefore, many families are unable to satisfy their yearly kilocalorie needs from their own food production. In a 2003/2004 survey among 2178 households in a sample of rural communities, 90% of families said that they did not produce enough food to last the previous 12 months. In other words, the great majority suffered from food insecurity at some point during the year. On average, they indicated having enough food, during the previous year, to last only 5 out of 12 months.[13] Key constraints were land quality, a lack of agricultural inputs, and poor transportation infrastructure.

Contributing to poor health status and poverty levels are the following facts: Nearly half of the Malagasy population is under the age of 15 years, and population growth, nationally, was estimated in 2006 to be at 3.3%.[14] This rate was among the top 5% (13 of 235) of all nations by this source for 2006. Early age at first pregnancy, low birth-spacing intervals, and high parity combine to result in poor maternal health, also negatively affecting infant and household child health. Maternal mortality is high (approximately 500 per 100,000 live births). Although infant mortality rates have decreased over the past decade, in 2003–2004 they remained high – at 58 deaths per 1000 children – due to poor hygiene, household crowding, poor nutrition, infectious diseases, and large family size.[12] Although 80% of women, in 2003–2004, knew about a method of family planning, contraceptive prevalence nationally was only 18%.[12]

According to the same national survey, women who are considered the most (extremely) poor are almost entirely rural. More than 40% of these women never attended school, and only 7% used a modern method of voluntary family planning. In rural communities, a woman will have, on average, 5.7 children in her reproductive lifetime. As a result of this, the rural population in Madagascar has nearly doubled since 1980 – to 13.4 million. This situation is compounded by the fact that rural populations frequently live in inaccessible areas that are distant from reliable transportation, economic markets, and social services. (Eighty-five percent of the Malagasy population live 5 km, or more than 1 hour's walk, from a basic health facility.[15])

Poverty and Resource Utilization

In rural areas throughout the world, poverty contributes to unsustainable levels of resource use as a means of meeting short-term subsistence needs. This is also the case in rural Madagascar, wherein population growth rates are particularly high and income from agriculture is low, resulting in high poverty and poor environmental protection.[16] In some rural areas of Madagascar (eg, near the moist forest), both absolute population size and population growth rate have been shown to be significantly associated with loss of forest cover on which local subsistence families heavily depend.[17] For people with few agricultural resources, especially the rural poor, high population growth rates undermine the potential for economic development that would otherwise occur with improved agricultural resources and more rational natural resource use.[18] Population-related issues pertaining to natural resource use, agriculture, and associated food security exacerbate existing inequities between urban and rural Malagasy, and between rural subsistence families and those moving closer toward the market economy. In short, overutilization of resources and high population growth rates are making the poor even poorer.

What's Being Done?

In September 2003, at the Durban World Parks Congress, the president of Madagascar, Marc Ravalomanana, made a startling announcement. Whereas, in many parts of the world, protected areas are diminishing in number and/or size, his “Durban Vision” aims by 2008 to increase by 3 times – from 1.7 to 6 million hectares – the amount of land under protected area status in this “biodiversity hotspot” island nation.[19] In November of the following year, the president presented his vision for the country – “Madagascar, naturellement,” or “Madagascar Naturally” – acknowledging that Madagascar is rich in biodiversity, critical to the country's future economic growth.[20] As a successful businessman, President Ravalomanana understands the importance of establishing the economic, as well as intrinsic, value of his country's natural resources (including 478 unique genera of plants and vertebrates, such as lemurs, the most endangered primate species), as part of a national, sustainable economic growth strategy.

As Madagascar is mainly rural, the president's vision affirms the interdependence between biodiversity, economic growth, poverty reduction, and the development of Madagascar's mostly rural communities. Toward this end, in 2006 the Government of Madagascar introduced a new park management system, the System of Protected Areas of Madagascar (SAPM), designed to simplify the creation of new protected areas for wildlife and flora and ways of supporting land use management around protected areas that contribute to sustainable development and poverty reduction. In December 2005, 1 million hectares were newly designated as protected areas, contributing to the achievement of the president's Durban Vision. In 2007, an additional 1,071,589 hectares (4137 square miles) came under SAPM management, through the establishment of 15 new protected areas.[21]

In addition to strong statements on the role of biodiversity conservation and rural development, the current government, which took office in 2002, placed health improvements among its top priorities. Similarly, commitment to voluntary family planning and reproductive health became expressed at the highest levels.[15] In 2003, the country developed a strategic plan for poverty reduction (PSRP). In keeping with the MDGs, the main goal of Madagascar's PSRP was to reduce poverty in the country, by half, over the subsequent 10 years.[22] Voluntary family planning, among other health interventions, figured prominently among the various poverty reduction strategies outlined in the country's PSRP.

Reflecting awareness of the contribution of family planning to economic and social development in the country, at the end of 2004 a new family planning strategy was developed (2005–2009), to increase demand, improve services, and create a favorable policy environment. To address the needs of populations in the more remote areas, the focus has been on increasing geographic and economic access to voluntary family planning and other health services and products. This effort aims to:

Improve people's health, so that they can work more productively in their fields;

Reduce pressure on the biodiversity-rich environments, caused by increases in household numbers (and the corresponding need for additional cropland); and

Promote trust, between the various development partners and local communities, by addressing immediate needs of community members.

In 2006, the Government of Madagascar established a Madagascar Action Plan for 2007–2012 to replace its PSRP. The Madagascar Action Plan is a 5-year plan to accelerate and better coordinate Madagascar's development process. It aims to help the country achieve its MDGs and overall economic development.[23] Of the 8 commitments contained in the Plan, one focuses on “cherishing the environment”; one on “rural development and a green revolution”; and another on “health, FP and HIV/AIDS.” This plan reflects bold commitments required for the country to emerge from poverty and to promote long-term economic development. Environmental conservation and human health interventions, including voluntary family planning, are key among these commitments.

The president, himself, provides leadership and consistent support toward achieving the MDGs and his “Madagascar Naturally” vision through keynote speeches at critical events, endorsing policies and lending a face – his face – to advocacy and education tools. The latter includes a recent documentary film explaining the president's vision for biodiversity conservation (USAID Madagascar's “A New Vision”). The president also openly articulated his view on the interrelatedness between environmental conservation and population pressures, in a recent publication entitled “Madagascar Naturellement: Birth control is my environmental priority.[24]” Nowhere has his commitment to health, and balancing population growth with sustainable natural resource use, been more explicitly expressed than at the wedding of his daughter. A traditional wish, at Malagasy weddings, is for the couple to have 14 children – 7 sons and 7 daughters. President Ravalomana wished the couple “a healthy life together…and 3 children.[26]”

Public support, to increase voluntary family planning nationally, includes his endorsement, in 2003, of the name change from the “Ministry of Health” to the “Ministry of Health and Family Planning,” making Madagascar one of the few places in the world where voluntary family planning as a key health intervention is so explicitly recognized. In 2004, the newly named Ministry launched its National Family Planning Program, and President Ravalomanana attended the event, giving the keynote speech. In that speech, he made a personal commitment to access to voluntary family planning for all Malagasy citizens.

As part of the president's commitment to expediting economic growth, he launched a rapid results initiative. As an example of how the initiative operates, the rapid results initiative approach was used, early on, in a focal area to increase family planning use, from 2% to 11%, within 50 days and increasing to 14% in 90 days.[25] This year, in 2007, the rapid results initiative for family planning use was extended nationally, as the capability to offer voluntary family planning services reached all public clinics in the country. This achievement illustrates the president's strong commitment to universal family planning access as one pathway to achieving economic growth and the MDGs.

Conclusion and Call to Action

A recent report analyzed the reasons why family planning has lost policy visibility, globally, and funding support on the basis of interviews with informants from developed and low-resource nations.[26] The study authors concluded that a key message, to regain support, should be voluntary family planning's relevance to reducing social inequity, in addition to its health benefits. In Madagascar, this message has been articulated, loudly and clearly, by representatives from development agencies, by public officials and, at the top, by the president himself. The message is also embedded in a larger, nation-building vision – “Madagascar Naturally” – which acknowledges the critical role of biodiversity conservation and rural development, including health improvements and fertility reduction, in the efforts toward achievement of overall poverty reduction and economic development.

As one report informant from a developing country expressed, “The population theme is both a threat and an opportunity. It needs to be better utilized…to rise above poverty.[26]” Madagascar stands out as an example of how the population theme has been – and continues to be – understood, appreciated, and used to address conservation issues, agricultural challenges, health problems, social inequities, poverty reduction, and the vision of rapid but sustainable economic growth. Madagascar also represents a country seeking, and experimenting with, creative solutions to the challenge of implementing poverty reduction initiatives that consider the interdependencies between human development and natural resource management, including biodiversity conservation.

With this vision and pathway forward, chances are greater for achieving measurable progress toward, if not achievement of, at least some of Madagascar's MDGs. However, as the former US Ambassador noted, “Madagascar cannot do it alone, and should not do it alone” (USAID Madagascar's “A New Vision”). For resource-limited countries in sub-Saharan Africa, including the Island of Madagascar, to get or stay “on track,” support is needed from all angles. Such support is, in fact, embodied in the eighth MDG – “Develop a global partnership for development” – to which all 191 nations pledged their commitment. Thus, inherent in the achievement of global MDGs is the responsibility of each country to help fellow countries achieve their national MDGs. Apparently it takes a village, after all – a global one.

Appendix: MDGs

The UN Millennium Declaration, signed in September 2000, commits the states to:

- Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Reduce by half the proportion of people living on less than $1 per day

- Reduce by half the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

- Increase the amount of food for those who suffer from hunger

- Achieve universal primary education

- Ensure that all boys and girls complete a full course of primary schooling

- Increased enrollment must be accompanied by efforts to ensure that all children remain in school and receive a high-quality education

- Promote gender equality and empower women

- Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and at all levels by 2015

- Reduce child mortality

- Reduce the mortality rate, among children under 5 years, by two thirds

- Improve maternal health

- Reduce, by three quarters, the maternal mortality ratio

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Halt, and begin to reverse, the spread of HIV/AIDS

- Halt, and begin to reverse, the incidence of malaria and other major diseases

- Ensure environmental sustainability

- Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programs; reverse loss of environmental resources

- Reduce, by half, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water. (For more information, see the entry on water supply)

- Achieve significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers, by 2020

- Develop a global partnership for development

- Develop further an open trading and financial system that is rule-based, predictable, and nondiscriminatory. This includes a commitment to good governance, development, and poverty reduction – nationally and internationally

- Address the least developed countries' special needs. This includes tariff- and quota-free access for their exports, enhanced debt relief for heavily indebted poor countries, cancellation of official bilateral debt, and more generous official development assistance for countries committed to poverty reduction

- Address the special needs of landlocked and small, island, developing states

- Deal comprehensively with developing countries' debt problems, through national and international measures, to make debt sustainable long term

- In cooperation with the developing countries, develop decent and productive work for youth

- In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable, essential drugs in developing countries.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Poverty Reduction and Millennium Development Goals: Recognizing Population, Health, and Environment Linkages in Rural Madagascar See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at earthlg@aol.com or to George Lundberg, MD, Editor-in-Chief of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Contributor Information

Lynne Gaffikin, Evaluation and Research Technologies for Health (EARTH), Inc., Portola Valley, California Author's email: earthlg@aol.com.

Jeffrey Ashley, Office of Basic Human Services USAID/Indonesia.

Paul D. Blumenthal, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California; Medscape General Medicine.

References

- 1.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. United Nations Millennium Declaration. September 8, 2000. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/english/law/millennium.htm Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 2.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Sustainable Development. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/index.htm Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 3.UN Millennium Development Goals. Available at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 4.United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2007. New York: United Nations; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations. Africa and the Millennium Development Goals. 2007 Update. New York: United Nations; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Bank Madagascar Country Brief. Available at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/MADAGASCAREXTN/0,,menuPK:356362~pagePK:141132~piPK:141107~theSitePK:356352,00.html Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 7.International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Available at: http://www.un.org/popin/icpd2.htm Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 8.United Nations Development Programme. Human development reports. 2003 Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2003/indicator/cty_f_MDG.html Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 9.World Bank Madagascar Country Brief. Available at: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/MADAGASCAREXTN/0,,menuPK:356362~pagePK:141132~piPK:141107~theSitePK:356352,00.html Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 10.USINFO.STATE.gov. Madagascar, United States sign Millennium Challenge Aid Compact. April 20, 2005. Available at: http://usinfo.state.gov/ei/Archive/2005/Apr/19-681391.html Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 11.Rural Poverty Portal website. Available at: http://www.ruralpovertyportal.org/english/regions/africa/mdg/index.htm Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 12.Institut National de la Statistique (INSTAT) and ORC Macro. Demographic Health Survey, Madagascar 2003–2004. Madagascar: INSTAT & ORC Macro; March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergeron G, Deitchler M. Report of the 2004 Joint Baseline Survey in the Targeted Areas of the PL480, Title II Program in Madagascar. Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) Project; November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wikipedia. List of countries by population growth rate. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_population_growth_rate Accessed October 17, 2007.15. Aramati M, et al. Using the SPARHCS approach to reposition family planning in Madagascar: a success story. Policy Project. December 2005.

- 15.Hunter LM. The Environmental Implications of Population Dynamics. Santa Monica, Calif: Rand Population Matters; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler JS, Moser CM. The effect of cloud cover from satellite images on the measurement of deforestation. forthcoming, Land Economics.

- 17.Alexandratos N. Countries with rapid population growth and resource constraints: issues of food, agriculture, and development. Popul Dev Rev. 2005;31:237–258. [Google Scholar]

- 18.USAID Madagascar. Conserving Madagascar's biodiversity. 2006 Available at: http://www.usaid.gov/missions/mg/about/biodiversity.html Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 19.Ravalomanana M. Remarks at the opening session of the Jan 2005 International Conference “Biodiversity: Science and Governance”; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madagascar creates 1 million hectares of new protected areas [press release] Arlington, Va: Conservation International; [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Monetary Fund. Republic of Madagascar: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Progress Report. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund; [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations Economic and Social Development. Madagascar Action Plan. United Nations. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/coordination/Alliance/MADAGASCAR%20ACTION%20PLAN.htm Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 23.Ravalomanana M. Madagascar naturellement: birth control is my environmental priority. World View Magazine for Peace Corps Alumni. Fall 2006. Available at: http://www.worldviewmagazine.com/issues/article.cfm?id=188&issue=43 Accessed October 17, 2007.

- 24.Malagasy Republic Minister of Health, as quoted in L'Express Journal on March 25, 2005

- 25.Lalasz R. The Future of the International Family Planning Movement. Population Reference Bureau. July 2005. Available at: http://www.prb.org/Articles/2005/TheFutureoftheInternationalFamilyPlanningMovement.aspx Accessed October 17, 2007.