Introduction

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor (SLCT) is a rare ovarian tumor that belongs to the group of sex-cord stromal tumors. These constitute less than 0.5% of ovarian tumors.[1] Most tumors are unilateral, confined to the ovaries, and are seen during the second and third decades of life. These tumors are characterized by the presence of testicular structures that produce androgens. Hence, many patients have symptoms of virilization depending on the quantity of androgen production. The second characteristic feature of these tumors is the degree of differentiation of structures in them. The presence of these structures determines whether the tumors are benign or malignant.[2] Twenty percent of SLCTs exhibit heterologous elements represented by endodermal elements such as cysts and glands and mesenchymal elements such as bone, cartilage or skeletal muscle. A gastrointestinal structure is rarely reported in these tumors.[3,4] We present the case report of a young woman with an SLCT along with management issues of the disease.

Case Report

A 19-year-old nulliparous woman came to the clinic with complaints of progressive oligomenorrhea of 2 years' duration. She had been amenorrheic for the past 7 months. She had also noticed a change in her voice for 1 year and excessive hair growth on her face, chest, and limbs for the last 2 months. In addition, she complained of vague abdominal discomfort. She was married for the last 4 months and denied any history of anorexia, weight loss, increased libido, or breast recession. Her medical and family history was unremarkable.

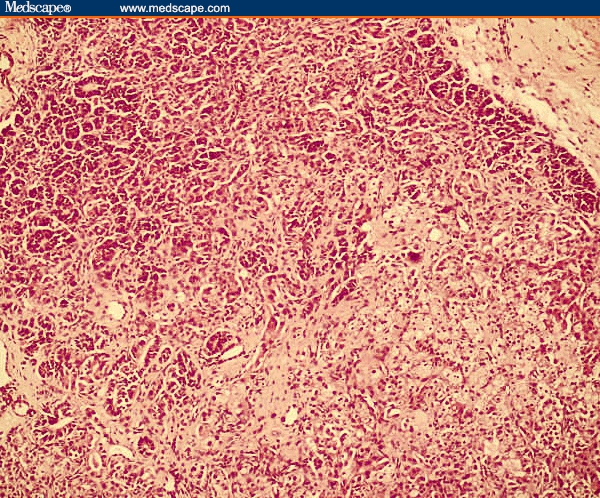

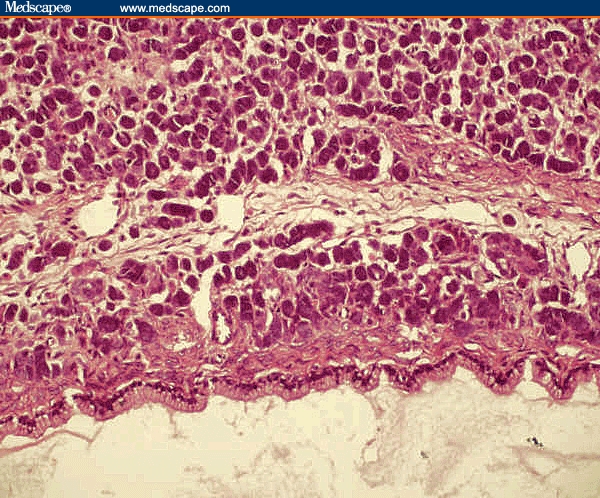

Her general physical examination was normal except for the presence of hirsutism and clitoromegaly. Vaginal examination revealed a firm and mobile cystic mass in the left adnexa. An ultrasound examination of the pelvis showed a 7-cm by 7-cm by 5-cm heterogeneous solid cystic mass replacing the left ovary. The right ovary and the uterus were normal. A hormonal profile in blood indicated excessive androgenic activity in the form of elevated serum testosterone level (2 ng/mL; normal, 0.2–1.2 ng/mL); however, levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), CA 125, and alphafetoprotein (AFP) were normal. Based on these findings, a provisional diagnosis of androgen-producing ovarian tumor was made. The patient underwent ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology, which revealed the presence of benign cystic cells. However, because there was a strong suspicion of malignancy, exploratory laparotomy was performed. Operative findings showed replacement of the left ovary by a 7-cm by 6-cm solid, grey-white, smooth-surface mass with intact capsule without spill and with no remnant healthy ovarian tissue. There was no spillage of tumor cells during surgery. The abdominal cavity was explored systematically but there were no deposits anywhere else in the cavity. The para-aortic lymph nodes were not enlarged. The right ovary was found to be slightly enlarged on examination. Left salpingo-oophorectomy was performed, including biopsy from the right ovary. Peritoneal washings were sent for cytologic examination for malignant cells. An omental biopsy was also done during the procedure. However, lymph node dissection was not performed. Frozen section of the resected specimen revealed it to be sex-cord stromal tumor. Gross examination of the pathologic specimen showed that it was an ovarian mass measuring 10 cm by 7 cm by 2 cm. The external surface was smooth. A cut section of the specimen revealed solid as well as cystic areas filled with clear fluid. The histopathologic examination showed a tumor composed of poorly formed cords, nests, and tubules of tumor cells. Tumor cells had hyperchromatic nuclei, a moderate amount of cytoplasm (Sertoli cells), and occasional mitosis. Interspersed between these were nests of polygonal cells with round nuclei and abundant granular cytoplasm (Leydig cells). Focal areas showed dilated glands lined by mucinous epithelium of gastrointestinal type (Figures 1 and 2). Retiform pattern was not seen. Right ovarian biopsy and peritoneal washing did not reveal any abnormal cells.

Figure 1.

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. Section shows cords of immature Sertoli cells and clusters of Leydig cells. Haematoxylin & eosin (× 100).

Figure 2.

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor with heterologous elements. Section shows tumor with heterologous elements showing intestinal-type epithelium. Haematoxylin & eosin (× 200).

Based on the above findings, a final diagnosis of ovarian sex-chord tumor (Sertoli-Leydig cell), stage IA with heterologous elements of gastrointestinal type, intermediate grade, was made. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day.

After the histopathology report was received, we had a detailed discussion of various treatment options with the patient. After her consent, 4 cycles of chemotherapy with a bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin regimen were administered 3 times a week. The patient tolerated the chemotherapy well, with no major complications. During 10 months of follow-up, the patient has resumed her periods, with resolution of her virilization symptoms. There is also no increase of her hirsutism. Repeat testosterone levels on follow-up were within normal range.

Discussion

We here present an unusual case of SLCT with heterologous elements. Heterologous elements are observed in approximately 20% of SLCT. These can be further separated into 2 basic types: endodermal elements and mesenchymal elements. The endodermal type is represented by gastric or intestinal type mucin-secreting epithelium. The mesenchymal elements are represented by immature cartilage and or skeletal muscle. The SLCT with heterologous mesenchymal elements are usually poorly differentiated in contrast to neoplasms with endodermal elements, which typically are of intermediate differentiation.[3] In our patient the heterologous element was in the form of mucinous epithelium of the gastrointestinal type. Though Meyer et al. described the presence of mucinous epithelium in a SLCT in 1930, the first illustration is in the case reported by McLester in 1936, who described a SLCT containing a cyst lined by nonmucinous cells and mucinous cells, including glandular cells.[5,6] The majority of these patients are seen during the second and third decades of life, with the average age at diagnosis 25 years. Around 50% of cases come to clinical attention because of progressive defeminization, as was seen in this patient.[1]

The most important prognostic factors in these tumors are their stage and degree of differentiation. In a review of 207 cases by Young and Scully in 1985,[1] all well-differentiated tumors were benign, whereas 11% of tumors with intermediate differentiation, 59% of tumors with poor differentiation, and 19% of those with heterologous elements were malignant. In another study of 64 patients who had intermediate or poorly differentiated SLCT, a survival rate of 92% was noted at both 5 and 10 years.[7]

Most of these tumors are unilateral and diagnosed in stage I, so conservative surgery in a young patient is an appropriate treatment. There have also been case reports of successful laparoscopic management of these tumors.[8] Adjuvant chemotherapy is considered for patients who have poor prognostic factors.

The malignancy rate in tumors with heterologous elements is 15% to 20%.[1] Adjuvant chemotherapy in stage I is given to those patients who have poorly differentiated SLCT or SLCT with heterologous elements or a metastatic tumor of any histologic type.[9]

The patient in this report received adjuvant chemotherapy for SLCT in stage I. The 2 factors responsible for this decision were incomplete staging of the tumor and the presence of heterologous elements on histopathologic study of the tumor. The following chemotherapy regimens were considered:

Cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide (PAC);[10]

Vincristine, actinomycin-D, cyclophosphamide (VAC);[11] and

Bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP).[12]

The BEP regimen is a comparatively safe chemotherapeutic regimen because it does not affect the fertility status of the patient.[12]

In conclusion, SLCT is a rare ovarian sex-cord tumor that usually occurs unilaterally. SLCT should always be considered in a young female patient who has symptoms of virilization and an ovarian mass on examination or investigation.

Management issues mostly revolve around the histopathology of the tumor. Poorly differentiated tumors require aggressive management because the chances of them being malignant are high. Intermediately differentiated tumors need an individualized approach. The patient should be involved in all decision making.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: A Rare Ovarian Tumor – Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor With Heterologous Element See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at pradiplekha@yahoo.co.in or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Rimpy Tandon, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Government Medical College & Hospital, Chandigarh, India.

Poonam Goel, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Government Medical College & Hospital, Chandigarh, India.

Pradip Kumar Saha, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Government Medical College & Hospital, Chandigarh, India Author's email: pradiplekha@yahoo.co.in.

Navneet Takkar, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Government Medical College & Hospital, Chandigarh, India.

RPS Punia, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College & Hospital, Chandigarh, India.

References

- 1.Young RH, Scully RE. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumours. A clinicopathological analysis of 207 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:543–569. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietrich JE, Kaplan A, Lopez H, Jaffee I. A case of poorly differentiated Sertoli-Leydig tumour of the ovary. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantzsch T, Stoerer S, Lawrenz K, Buchmann J, Strauss H-G, Koelbl H. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;264:206–208. doi: 10.1007/s004040000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathur SR, Bhatia N, Rao IS, Singh MK. Sertoli Leydig cell tumour with heterologous gastrointestinal epithelium: a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer R. Tubulare(testikulare) und solide Formen des Andreioblastoma ovarii and ihre Beziehung zur Vermannlichung. Beitr Z path Anat Allg Path. 1930;84:485–520. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLester JB. Arrhenoblastoma: a special type of teratoma. Arch Interm Med. 1936;57:773–786. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaloudek C, Norris H. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors of the ovary. A clinicopathological study of 64 intermediate and poorly differentiated neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:405–418. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kriplani A, Agarwal N, Roy KK, Manchanda R, Singh MK. Laproscopic management of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumours of the ovary. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sood AK, Gershenson DM. Management of early-stage ovarian cancer. In: Bristow RE, Karlan BY, editors. Surgery for Ovarian Cancer: Principles and Practice. London, UK: Taylor and Francis; 2005. pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gershenson DM, Copeland LJ, Kavanagh JJ, et al. Treatment of metastatic tumour of the ovary with cisplastin, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:765–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz PE, Smith JP. Treatment of ovarian stromal tumours. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125:402–411. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershenson DM, Morris M, Burke TW, et al. Treatment of poor-prognosis sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary with the combination of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:527–531. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]