Abstract

Context

Although physician influence can be especially powerful with older adults, relatively little is known about how primary care physicians (PCPs) interact with their patients regarding lifestyle issues.

Objective

To document the length of time that PCPs discuss lifestyle issues with their older patients and to examine patient, physician, and contextual correlates.

Design

Descriptive and multivariate analysis of videotapes of physician-patient encounters.

Setting

Medical encounters from 3 primary care ambulatory settings.

Patients

There were 116 ongoing medical encounters with patients aged 65 years or older.

Main outcome measures

Total time spent in physical activity (PA) discussions and total time spent discussing PA, nutrition, and smoking during the medical encounter.

Results

Very little time was spent in lifestyle discussions. On average, PA was discussed for less than a minute (58.28 seconds) and nutrition for slightly less than 90 seconds (83.11 seconds). Only about 10% of the average 17-minute, 22-second encounter was spent on physical activity, nutrition, or smoking topics. Physician supportiveness score (beta = 8.92, P ≤ .001) and the number of topics discussed (beta = 106.39, P ≤ .001) were significantly correlated with the length of all lifestyle discussion. Lifestyle discussions were also more likely to occur during longer visits.

Conclusion

There is a critical need for additional training of primary care providers on how to discuss lifestyle issues in the most time-efficient but effective manner to achieve positive behavior change associated with improved health outcomes. There is also a need for the institutionalization of policies to encourage more lifestyle discussions.

Introduction

The influence of lifestyle factors on health and well-being is now well documented.[1–3] What is less known but is also increasingly documented is the potency of these same lifestyle factors in predicting morbidity and mortality in later life.[4–6] Although healthcare providers can have a strong influence on patient behaviors,[7–9] relatively little is known about how primary care physicians (PCPs) interact with their patients regarding lifestyle issues.[10,11] Physician influence can be especially powerful with older adults who make multiple ambulatory visits throughout the year[12] and who traditionally hold physicians in high regard.[7] In particular, the American College of Preventive Medicine position stand recommends that “primary care providers incorporate behavioral interventions such as related to physical activity and poor diet into their practice based on evidence of strong epidemiological linkages between lifestyle factors and health outcomes.”[13]

Recent literature has reported several factors associated with lifestyle discussions with patients, including the role of patient, physician, and contextual factors.[14–16] Although lack of physician consultation time has been suggested as a major barrier to lifestyle discussions and counseling,[17] there is actually scant evidence on how much time doctors spend on different types of lifestyle discussions and factors associated with the amount of time actually spent on such discussions.[18,19]

The primary purpose of this study was to examine doctor-older patient medical encounters to document the length of time that PCPs actually discuss lifestyle issues with their older patients in ongoing medical encounters, where especially little is known. This study addresses questions such as how much time primary care doctors actually spend on different lifestyle topics and what percent of the total encounter time is devoted to such discussions with older adults. It also examines the extent to which encounters involve the mention of a single lifestyle domain or whether multiple lifestyle discussions are the norm, once the topic has been broached. We chose to focus on physical activity, nutrition, and smoking, because these behaviors are leading causes of premature death in the United States,[2] and have thus received substantial attention in the behavior change research literature.[20]

In addition, building on our previous study of factors influencing lifestyle discussions,[16] we were interested in assessing what patient, physician, or contextual factors might be related to the amount of time spent in such lifestyle discussions. Because so little research has been conducted on this topic, there were few existing data on which to base specific hypotheses. Our approach therefore was to examine the same set of factors that we previously examined in relationship to whether or not such discussions took place at all.[16]

Methods

Sample Recruitment

Between August 1998 and July 2000, 434 older-patient visits to 36 physicians were videotaped at 3 healthcare sites selected to provide a broad mix of practice types, PCPs, and older adults. This investigation will focus on a subset of 116 of these encounters as explained below. The 3 sites included an academic medical center, an inner city private practice clinic, and a managed care organization. Patients were recruited in the waiting room of physician offices prior to their visit. To be eligible for the study, patients had to be at least 65 years of age, identify the physician as their usual source of primary care, and must have seen this physician on at least 1 prior occasion. All recruited physicians, patients, and companions accompanying the patients were told that the purpose of the study was to examine doctor-older patient interactions; no mention was made about which kinds of communication or outcomes were to be assessed. Further information on study design and sample recruitment strategies for the complete original dataset is available elsewhere.[21,22] Patients, companions accompanying the patient into the examination rooms, and physicians provided written informed consent before participating in the study, which was approved by the institutional review board of St. Louis University.

From the original dataset that was limited to the first recorded encounter with any particular patient, 116 doctor-older patient encounters that featured 116 unique patients and 33 unique physicians were included in the current study. Delving into the larger precoded secondary data set, we wanted to address some supplementary research questions. Encounters featuring PA discussions were targeted because of our interest in this area. Because of lack of funding it was not possible to reassess all of the original tapes. Other lifestyle discussions could be present as well, but PA had to be included in the discussion for the current analysis. The research protocol for this supplemental study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Texas A&M University.

Data Collection

Videotapes were made of each encounter featuring a participating patient and physician dyad to provide data via direct observation. Additionally, all participating physicians, patients, and patients' companions involved in the encounters were asked to fill out 1 or more self-administered surveys. Immediately prior to the visit, patients were surveyed about their demographic information, their overall satisfaction with the physician they were scheduled to see, whether that physician was the patient's regular source of care, and the purpose of the visit. Directly following the visit, the patient filled out another survey questionnaire asking about his or her health status, using questions from the SF-36.[23,24] Physician surveys asked for information about specialization, practice type, length in practice, other geriatric training, and demographic status. Patient companions also provided information about themselves. Videos were coded according to selected items from the Assessment of Doctor-Elderly Patient Transactions (ADEPT) system.[25]

For the supplemental research questions, a coding sheet was developed with operational definitions for each lifestyle factor. The coding sheet drafts were reviewed by graduate students in an upper-level course on health promotion and aging. After finalizing the coding sheet, 2 student coders – 1 from a medical school and 1 from a public health school – spent 2 weeks training by filling out practice sheets; research staff then checked these sheets, noted problems, and provided additional training as necessary. Once the trainers were assured the coders understood the coding categories and operational definitions, the tapes were coded. All tapes were coded independently, with informal checks occurring periodically to ensure the coders stayed within training parameters.

Consistency analysis between the 2 trained videotape coders was performed for several variables. Interrater agreement between the 2 coders was evaluated by randomly selecting 10% of the videotapes for double coding. The coders were not aware of the results of the prior coding. Kappa statistics, which evaluate the extent of agreement between 2 or more independent evaluations of a categoric variable and take into account the extent of agreement that could be expected above and beyond chance alone were computed for dichotomous variables. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were computed for numeric variables.

The extent to which the coders agreed on the length of discussions about PA, nutrition, and smoking and the level of agreement regarding the number of discussions about these lifestyle topics was examined. Agreement between the 2 coders was high for the talk time and count of discussions. The average ICC for the talk time for each of the lifestyle behaviors was 0.998. The ICCs for the number of discussions within each lifestyle topic ranged from a low of 0.937 (for discussions about nutrition) to 1.00 (PA and smoking). The average ICC for these variables was 0.979.

Measures

Dependent Variables

Two dependent variables were used in the current analysis: total time spent in discussion of PA and combined total time spent in discussion of all 3 lifestyle factors during the primary care visit. Total time spent in discussion of nutrition and total time spent in discussion of smoking were also examined at a descriptive level but were not included in multivariate analysis because of the small sample size available for each variable. Only 70 cases included nutrition discussion and 19 included talk about smoking. Each time variable was coded in seconds. Occurrence of discussion of these lifestyle topics was recorded if the physician mentioned the topic in any context. The definition of PA discussion was not restricted to talk about structured exercise programs but was inclusive of the broader PA concept promulgated recently by public health advocates. Whereas the initiator of the conversation was also recorded, the depth of discussion (eg, level of topic knowledge on the part of the patient, numbers and types of subtopics, and party who introduced 1 or more subpoints) was not measured.

Independent Variables

The patient demographic variables included age, gender, ethnicity/race (coded as non-Hispanic white vs black and/or Hispanic), education (coded as college graduation vs less), and physical functioning score as assessed by a subscale from the SF-36 questionnaire,[23,24] which ranges from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores reflecting more positive outcomes.

Physician variables included age, gender, race (coded identically to the patient race variable), and whether the physician had received any geriatric training, including residency training, medical school coursework, and any continuing medical education activities (coded dichotomously as yes/no). Physician supportiveness scores used in these analyses were calculated using the ADEPT supportiveness scale, which ranges from 0 to 48 points, with higher scores indicating a more supportive physician. Physicians received higher supportiveness scores for activities such as visual attentiveness, eliciting and acknowledging patient verbal and nonverbal communications, and making empathetic statements. For more information on the psychometrics of this scale, see Teresi and colleagues.[25]

Contextual variables included the site of care, the length in years of the patient-physician relationship, whether a companion was present at the visit, the number of lifestyle topics the physician discussed during the visit (coded as 1 - PA only vs more than 1), and the patient's stated reason for the medical visit (coded as acute versus nonacute). Acute visits were defined as those for which the patient identified an acute medical concern among the reason(s) for the visit. Total length of visit was included as a covariate in the multivariate analyses.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means and frequencies, bivariate correlations, and univariate linear regressions were carried out on the data using SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). The prevalence and length of discussion for the 4 lifestyle variables were computed, and the potential influence of total visit length was investigated descriptively using stratification analyses.

To critically examine factors associated with total time of lifestyle discussions (eg, we believed that the length of lifestyle discussions when a companion was present would differ from that of patient-only encounters), the independent variables mentioned above were included in full multivariate linear regression models on PA discussion length and combined lifestyle discussion length. The regressions were run using the STATA 8.2 Intercooled software package (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

Because each physician saw 1 or more patients but worked at only 1 site, and because the site and doctor identifier variables were highly collinear, site was eliminated from the multivariate model. Because physicians saw more than 1 patient, the encounters potentially are not independent of one another. Nonindependence of observations biases the standard errors and subsequent significance tests.[26] To correct the standard errors and inference tests, we used the cluster option in STATA.[27] All multiple regressions were then clustered on the doctor identifier to control for geographic site of practice and individual practice style while focusing the analyses at the encounter level. Of the 116 videotaped visits coded for this project, 107 were retained for use in the multivariate linear regressions. The truncated sample excluding cases with any missing data exhibited statistically similar descriptive characteristics to those of the larger group (data not shown). Although the number of unique physicians, and thus potential clusters, decreased from 33 to 32, the lost physician had only contributed 1 case to the larger sample. This loss is therefore not expected to skew the multivariate results.

We also ran a separate multiple logistic regression to investigate what factors correlated with whether the combined lifestyle discussion was a minute or less in length or more than a minute long, also controlling for the clustered observations. The results are reported as odds ratios below. One minute was chosen as the cut off point for the dependent variable creation because of its proximity to the sample median for the combined lifestyle discussion (63 seconds, not shown) while being a quantity a physician could measure in his or her practice.

We also performed a Bonferroni t test in 1-way ANOVA using SPSS to measure the difference in mean length of combined lifestyle discussion, mean length of PA discussion, and mean visit length among the 3 sites. This was done to elucidate the potential differences that may be expected to occur between an academic medical center and, primarily, a managed care organization in these 3 values. We reasoned that the managed care facility would have significantly shorter times for all 3 values than would the academic center, and would at least differ from the inner city clinic.

Results

Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the 116 unique patients in the sample population were, on average, in their early to mid-70s (average age 73.6 years). The majority of patients were white (87.6%), female (55.8%), and had less education than a college degree (69%). SF-36 physical functioning subscale scores ranged from 5 to 100 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points (mean = 62.47).

Table 1.

Independent Variables: Patient, Physician, and Contextual Characteristics of the Doctor-Older Patient Encounter Sample

| Sample Characteristics (N = 116) | Percent or Averageof Sample |

|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |

| Age | |

| Average | 73.6 years |

| 65–74 years | 62.5% |

| 75–84 years | 27.7% |

| ≥ 85 years | 9.8% |

| Gender | |

| Female | 55.8% |

| Male | 44.2% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 87.6% |

| Black/Hispanic | 12.4% |

| Education | |

| College graduation or more | 31% |

| Less than college graduation | 69% |

| SF-36 Physical Functioning Scale score | |

| Average | 62.4 points |

| Physician Characteristics* | |

| Age | |

| Average | 49.4 years |

| < 50 years | 61.9% |

| ≥ 50 years | 38.1% |

| Gender | |

| Male | 80.7% |

| Female | 19.3% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 92.1% |

| Black/Hispanic | 7.9% |

| Geriatric Training | |

| No | 74.6% |

| Yes | 25.4% |

| Physician ADEPT Supportiveness Score | |

| Average | 17.7 points |

| Contextual Characteristics | |

| Site of Care | |

| Academic medical center | 36% |

| Managed care clinic | 58.8% |

| Inner city private practice | 5.3% |

| Length of Patient-Physician Relationship | |

| Average | 6.27 years |

| ≤ 1 year | 30.3% |

| > 1 and ≤ 3 years (median) | 22.9% |

| > 3 and ≤ 10 years | 28.5% |

| > 10 years | 18.3% |

| Presence of Companion | |

| Yes | 19.3% |

| No | 80.7% |

| Number of Topics Discussed | |

| One (PA alone) | 35.3% |

| More than one | 64.7% |

| Reason for visit | |

| Acute | 15% |

| Nonacute | 85% |

| Length of Visit | |

| Average | 17 minutes, 22 seconds |

n = number of doctor-patient encounters, not individual physicians.

The unit of analysis was the medical encounter. As such, the physician sample characteristics are presented for all 116 encounters, instead of by individual physician, thereby effectively weighting each physician by the number of patients he or she saw. The average physician age was approximately 49.4 years. The physicians were also predominantly white (92.1%) and male (80.7%), with a quarter (25.4%) having received geriatric training. The average ADEPT physician supportiveness score was 17.74 points on a scale of 0 to 48 points; scores ranged from 9 to 30.

The visit length, or time the physician spent in the room with the patient and/or companion, averaged about 17 minutes (17:22), ranging from slightly more than 5 minutes (5:04) to nearly 46 minutes (45:53). Companions were present in less than a fifth (19.3%) of the encounters. Most visits (85%) were routine, nonacute encounters. Physician-patient relationships featured in this study averaged 6 years, 3 months in duration, but spanned a range of less than 1 month to 44 years.

We ran an independent sample t test to examine the difference between the 116 cases where PA was mentioned and the remainder of the 434 cases (N = 307 with complete data) from the original dataset[21,22] where no PA discussion occurred. As anticipated from our original analyses that revealed several correlates of PA encounters, the cases with lifestyle discussion were significantly different on several key variables. In PA encounters as compared with encounters where no lifestyle discussion occurred, patients were more likely to be male, more likely to be white/non-Hispanic, and were more likely to be educated. Physicians were slightly older, more likely to be white/non-Hispanic, and were more supportive. Also encounters were more likely to be coded as nonacute in PA encounters.

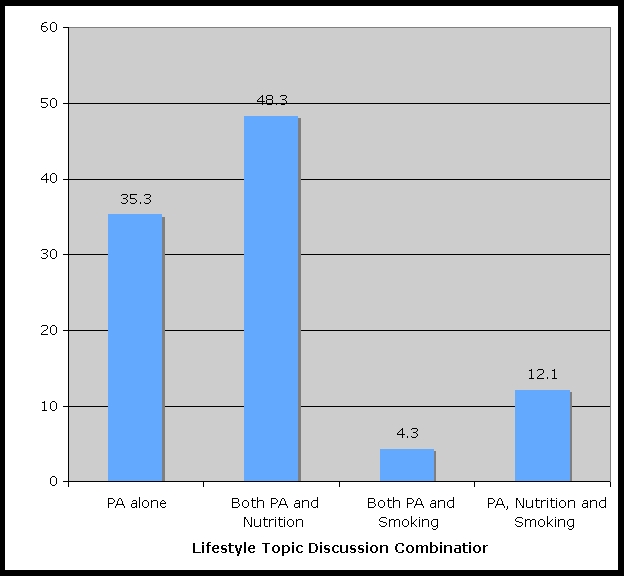

Lifestyle Discussions: Prevalence and Length

Although all encounters had to feature some discussion of PA to be included in this analysis, almost two thirds (64.7%) also contained some discussion about smoking, nutrition, or both. The Figure presents the breakdown of lifestyle discussions by prevalence of discussion. Discussing both nutrition and PA – at 48.3% of encounters – was the most common way to present lifestyle talk, followed by talking about PA alone (35.3%). Combining PA, nutrition, and smoking discussions into a single visit ranked third at 12.1% of the encounters, whereas the PA and smoking discussion combination was seen rarely, at only 4.3% of all encounters.

PA was discussed, on average, for almost a minute (58.28 seconds; range: 2 seconds to 7 minutes, 11 seconds); this represented 5.6% of the average visit time. Among those 70 respondents who discussed nutrition, talk lasted an average of 1 minute 23 seconds (83.11 seconds; range: 2 seconds to 9 minutes, 13 seconds) and represented 6.3% of those respondents' average visit time. Although lengthier than physical activity talk, discussion about nutrition was still shorter than the average discussion about smoking (113.89 seconds; range: 2 seconds to 16 minutes) for the 19 patients who participated in talk about this lifestyle issue; this time represented 6.2% of their average visit length. In total, all the lifestyle discussion that took place averaged 2 minutes, 7 seconds across the 116 encounters (range: 2 seconds to 20 minutes, 6 seconds) and represented about one tenth (12.2%) of the total average visit time. The average time spent in all lifestyle discussion was less than the 2 minutes, 34 seconds average length of medication discussion across these same encounters.

The influence of total visit length on the prevalence and length of discussions was initially investigated using simple stratification. Encounter length was broken down into 3 clinically relevant groups: those encounters lasting less than or equal to 10 minutes, those lasting longer than 10 and up to 20 minutes, and those lasting longer than 20 minutes. In data not shown, those encounters lasting longer than 20 minutes consistently included more types of lifestyle discussion than did shorter visits; lifestyle discussions also lasted a longer time in this stratum than they did in the shorter strata. Significant differences were seen for the percent of encounters featuring smoking discussion, the percent featuring discussion of more than 1 topic, and the average time of PA, nutrition, and total lifestyle talk. In all cases of significance across visit length strata, those visits lasting 10 minutes or less and those visits lasting longer than 10 and up to 20 minutes did not differ significantly from one another.

Correlates of Lifestyle Discussion Length

As shown in Table 2, none of the factors and covariates that we examined had any significant correlation with the length of PA discussion when examining seconds of talk time. Furthermore, only the physician ADEPT supportiveness score (beta = 8.92, P ≤ .001) and the number of topics discussed (beta = 106.39, P ≤.001) were significantly associated with the length of all lifestyle discussion.

Table 2.

Multivariate Models: Influence of Patient, Physician, and Contextual Characteristics on the Length of Lifestyle Discussions

| Characteristic | Description | Physical Activity Discussion (1-second change) | All Lifestyle Discussion (1-second change) |

|---|---|---|---|

| beta(95% CI) | beta(95% CI) | ||

| Patient Age(1-year change) | Linear | −1.65 (−4.33, 1.04) | −1.34 (−6.87, 4.18) |

| Patient Gender | Female compared to male | −7.55 (−38.04, 22.94) | 36.94 (−25.33, 99.21) |

| Patient Race | White compared to non-white | −24.61 (−74.86, 25.64 | −30.67 (−98.19, 36.85) |

| Patient Education | College educated compared to less than college | 6.98(−40.64, 54.60) | 53.84(−37.94, 145.63) |

| Patient SF-36 Physical Activity Score(1-point change) | Linear | −0.38 (−0.85, 0.09) | 0.53(−0.15, 1.21) |

| Physician Age (1-year change) | Linear | −0.47(−2.15, 1.22) | −0.31(−4.59, 3.97) |

| Physician Gender | Female compared to male | −23.15 (−52.51, 6.22) | −52.40(−149.95, 45.16) |

| Physician Race | White compared to non-white | 5.75(−52.29, 63.80) | −57.59 (−151.96, 36.78) |

| Physician Geriatric Training | Has training compared to does not have training | −6.21 (−36.11, 23.68) | −57.75 (−129.02, 13.53) |

| Physician ADEPT Supportiveness Score(1-point change) | Linear | 1.50(−0.96, 3.97) | 8.92(3.05, 14.78)‡ |

| Length of Doctor-Patient Relationship(1-year change) | Linear | −1.03(−2.48, 0.42) | −3.35 (−7.38, 0.67) |

| Companion Present | Has companion compared to does not have companion | 30.84 (−16.11, 77.79) | −12.00 (−98.86, 74.85) |

| Number of Topics Discussed | > 1 compared with only 1 (PA) | 10.42 (−16.27, 37.10) | 106.39 (51.14, 161.64)* |

| Reason for Visit | Acute compared to non-acute | −30.92 (−63.85, 2.00) | −62.74(−146.56, 21.08) |

| Length of Visit | Linear | 0.02(−0.01, 0.06) | 0.07(−0.01, 0.16) |

| Constant | 187.53(−20.42, 395.49) | −94.46(−505.54, 316.62) |

P ≤ .001

n = 107

Note: All variables entered simultaneously and clustered on doctor identifier.

CI = confidence interval

Odds of Having Longer Lifestyle Talks

Table 3 provides the results of the logistic regression of the patient, physician, and visit contextual characteristics on the length of all lifestyle discussions combined when examining length in a dichotomous fashion. This multivariate model showed that the odds of an encounter featuring more than 1 minute of lifestyle discussion instead of 1 minute or less were more than 4 times greater if the encounter featured discussion about more than 1 lifestyle topic than if it featured only discussion about PA. Additionally, the total length of visit proved to affect the total length of all combined lifestyle discussion to a smaller, but still statistically significant, extent. Each additional minute of visit time increased the odds that more than 1 minute was spent on lifestyle discussion (compared with less than 1 minute) by 12%.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression of Patient, Physician, and Visit Characteristics on All Lifestyle Discussion Length, Dichotomized

| All Lifestyle Discussion (> 1 Minute vs ≤ 1 Minute) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Referent | OR (95% CI) |

| Patient Age | 5-year increase | 1.26 (0.82, 1.95) |

| Patient Gender | Male | 2.76 (0.82, 9.28) |

| Patient Race | Non-white | 0.59 (0.16, 2.16) |

| Patient Education | Less than college educated | 1.39 (0.56, 3.43) |

| Patient SF-36 Physical Activity Score | 5-point increase | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) |

| Physician Age | 5-year increase | 0.92 (0.66, 1.26) |

| Physician Gender | Male | 0.24(0.03, 1.78) |

| Physician Race | Nonwhite | 0.37 (0.02, 7.41) |

| Physician Geriatric Training | Does not have training | 0.70(0.17, 2.93) |

| Physician ADEPT Supportiveness Score | 5-point increase | 1.30 (0.64, 2.63) |

| Length of Doctor-Patient Relationship | 1-year increase | 0.95 (0.89, 1.02) |

| Companion Present | No | 0.83(0.34, 2.05) |

| Number of Topics Discussed | One topic discussed (PA) | 4.44(1.31, 15.02)* |

| Reason for Visit | Nonacute | 0.21 (0.02, 1.73) |

| Length of Visit‡ | 60-second increase | 1.12 (1.00, 1.25)* |

P ≤ .05

n = 107

Note: All variables entered simultaneously and clustered on doctor.

Note: 95% CI lower bound is 1.0046.

CI = confidence interval

Effect of Site

Using the Bonferroni t test in 1-way ANOVA, we compared the means across the 3 sites for the following variables: length of PA discussion, length of all combined lifestyle discussion, and total visit length (Table 4). Data showed that the academic center consistently differed from the managed care organization for all variables, whereas the inner city private practice was always grouped with the managed care organization and differed from the academic center only in average visit length. For PA, managed care encounter discussions averaged slightly more than half the length of those at academic centers, and managed care encounters featured the shortest average PA discussions. For all lifestyle discussions combined and the total visit, the inner city private practice averaged the shortest lengths, whereas the academic center always averaged significantly longer than the managed care site. For lifestyle discussion, we found that the academic center average was more than twice that of the managed care site, while for total visit length, it was nearly twice as long.

Table 4.

Difference in Means of Length of Physical Activity Discussion, Length of All Lifestyle Discussion Combined, and Total Visit Time Compared Across Sites

| Academic Medical Center | Inner City Private Practice | Managed Care Organization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 41 | n = 6 | n = 67 | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Physical Activity Discussion, seconds | 82.61a(91.53) | 50.00a,b(69.62) | 45.37b(60.91) |

| All Lifestyle Discussion, seconds | 196.83a(189.49) | 58.67a,b(76.48) | 93.55b(163.55) |

| Total Visit Time | 1417.71b(462.49) | 762.50a(378.28) | 852.21a(371.60) |

Note: Groups bearing same letters are not significantly different from one another at P ≤ .05.

SD = standard deviation

Discussion

These analyses provide concrete evidence of the very small amount of time spent in lifestyle discussions between older patients and their PCP, even when selecting encounters known to involve at least 1 type of lifestyle discussion (PA). Despite the strong epidemiologic link between lifestyle factors and typical health concerns of patients,[28,29] only about 10% of the actual encounter, which averaged approximately 17 minutes, is spent on any of the major lifestyle topics (eg, PA, nutrition, or smoking). The minute or 2 spent bringing up exercise or nutrition is far less than even the briefest estimates for effective brief counseling in these areas.[8,30,31] These data do suggest that time does matter, and that lifestyle discussions, at least in these encounters, were additive. Consistent with other findings in predominantly younger populations,[10] we see that lifestyle discussions were more likely to occur in longer visits, and the number of lifestyle topics discussed was also associated with visit length. Physician supportiveness remained as one of the strongest correlates, confirming our earlier finding of an association between an empathetic/listening physician style and more psychosocial and lifestyle talk.[16] That length of patient visit varies by health organization setting, with academic medical centers having the luxury of more patient time, is not a new finding.[18] This study provides new insight into how that extra time might be spent, that is, in substantially longer – although still relatively short – lifestyle discussions.

It is probably not too surprising that fewer factors emerged as predictors of the length of lifestyle discussions compared with the findings of our earlier study, which revealed several correlates that predicted any such discussion.[16] In part this is because the present study drew on a subset of encounters that were already significantly different from the original study dataset. For example, whereas the reason for visit emerged as one of the major correlates with whether a lifestyle subject was broached or not, once a lifestyle discussion was started, the reason for the visit played less of a role in the length of the actual conversation in the present study and in other studies.[19] In summary, other than time and physician support style, there were few predictors of the duration of lifestyle conversations. The failure to identify many systematic patient, physician, or contextual correlates suggests that the duration of lifestyle talk is a random event more than a planned event based on specific patient needs.

Although the findings from this study are intriguing, several limitations must be noted. First, these encounters occurred nearly 10 years ago, which begs the question of whether greater awareness of the health benefits of lifestyle factors has resulted in more time and attention being paid to these factors. Similarly, the impact of changes in the composition of the physician labor force might also have resulted in different findings. For example, less than 20% of the observed encounters included female physicians, and women are now far more represented in clinical practice. Although we did not find any gender differences in predicting the presence or absence of lifestyle discussion,[16] this is an area worthy of further study.

Unfortunately, we were not able to identify any more recent studies with direct observation of large numbers of older patient-doctor interactions around lifestyle topics to document the direction and magnitude of changes over time. Comparisons with more recent data will be instructive, although caution in interpretation is needed because prevalence of lifestyle discussions varies by mode of data collection (eg, direct observation, chart review, survey of physicians or patients).

In addition, these analyses are based on a single encounter, which may mask the presence and extent of lifestyle conversations in earlier or later encounters. They also represented a mix of visit types, including both ongoing chronic care and acute visits. However, given the strong link between lifestyle factors and health outcomes in older adults, there is growing recognition that such discussions should be part of every encounter.[8,32]

Finally, these analyses just focus on time and not on quality of the interaction. It would be helpful to know whether and which aspects of behavioral counseling (ie, reminding the physician to assess current behaviors, providing general advice for making a suggested change, agreeing to collaborative goals, assisting in achieving those goals by tailoring advice to the patient needs, and arranging follow-up visits and activities) might have been used and whether these factors were related to specific patient outcomes.[31]

These findings suggest the need for both clinical and policy interventions. Clinically, there is a critical need for additional training of primary care providers to help them know how to bring up lifestyle issues in the most time-efficient but effective manner to achieve positive behavior change associated with improved health outcomes. Basic skills in behavioral counseling are needed[33] and there should be a functional referral system for high-risk patients who need more attention outside of the medical encounter. In the PA arena, for example, in the United States, Web-based educational outlets are being set up to provide information about evidence-based best practices and opportunities for PA.[34–36]

There are also some encouraging signs on the practice/policy horizon that reaffirm the importance of lifestyle discussions in medical encounters with older adults. Perceived or real time restraints can be addressed by policy and practice changes that encourage physicians to engage in lifestyle discussions by defining such discussions as part of quality care and offering financial incentives to compensate for added clinical time.

To shift doctor behavior around making lifestyle recommendations to older patients, doctors need to recognize the value of such approaches to improve the health and well-being of their older patients.[37] Two new policy changes in the United States can be anticipated to increase physician attention to these important issues. These include making PA a documented part of the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure and introducing “Welcome to Medicare” preventive visits.[38,39] Such monetary incentives are being explored in other countries as well. For example, in Australia under the universal health insurance scheme Medicare, doctors can bill patients for specific encounters around chronic illness management and health assessments for older people.[40,41] Under the chronic illness encounters, doctors develop care plans that include lifestyle tasks (eg, improve exercise, improve healthy diet). It is anticipated that such approaches will increase doctor's implementation of lifestyle recommendations for older people.

This study documents the limited amount of time spent in lifestyle discussions between doctors and their older patients. The existing body of literature about lifestyle discussions in medical encounters focuses primarily on PA in younger populations, but this study brings up the importance of such conversations with older patients as well. Future research is needed to understand more about the nature of these interactions and the implications for patient outcomes. The unanswered question is still how much time is needed to achieve optimal results and how to structure clinical interactions for maximal health benefit, especially for geriatric patients whose downward health trajectories might be slowed by appropriate behavioral changes.

Figure 1.

Frequency of lifestyle discussion (n = 16).

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Mary Ann Cook for making the original data set available through funding from National Institute on Aging Small Business Innovation Research Contract Number N43-AG-6-2118 and Grant Number R44AG15737. We also thank those who worked on coding the supplemental data: Paula Yuma, Jay Jezierski, and Melisa Jezierski. Special thanks to Kate Barron and Dongling Zhan for their assistance on the analysis and to Harriet Radermacher for assistance with manuscript preparation. This manuscript was envisioned while the senior author was on Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia, and benefited from the examination of clinical and aging issues from an international perspective.

Funding Information

This study was funded by a grant from the Texas A&M Health Science Center School of Rural Public Health/Scott and White Health Plan Health Services Research Program and from The Center for Community Health Development Prevention Research Centers Program, supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cooperative agreement number 5U48DP000045.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Lifestyle Discussions During Doctor-Older Patient Interactions: The Role of Time in the Medical Encounter See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at mory@srph.tamhsc.edu or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in MedGenMed via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Marcia G. Ory, School of Rural Public Health, Texas A&M Health Science Center, College Station, Texas. Email: mory@srph.tamhsc.edu.

B. Mitchell Peck, Department of Sociology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma. Email: bmpeck@ou.edu.

Colette Browning, Institute of Health Services, Monash University, Victoria, Australia.

Samuel N. Forjuoh, Department of Family & Community Medicine, Scott & White Clinic, Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine, Temple, Texas.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: The burden of chronic diseases and their risk factors: national and state perspectives 2004. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/burdenbook2004 Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 2.Mokdad A, Marks J, Stroup D, Gerberding J. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. [correction published in JAMA. 2005;293:293–298] JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: At a glance – healthy aging: preventing disease and improving quality of life among older Americans. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/heathy_aging.pdf Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 5.Ory M, Hoffman M, Hawkins M, Sanner B, Mockenhaupt R. Challenging aging stereotypes: designing and evaluating physical activity programs. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3 suppl 2):164–167. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ory M, Schickedanz A, Suber R. Health promotion, disease prevention and chronic care management: wellness perspectives across the continuum of care. In: Evashwick C, editor. Continuum of Long-Term Care. 3rd ed. Albany, NY: Delmar; 2005. pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adelman R, Greene M, Ory M. Communication between older patients and their physicians. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE, Dzewaltowski DA. Physical activity promotion through primary care. JAMA. 2003;289:2913–2916. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling to Promote Physical Activity: Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. pp. 611–624. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaudoin C, Lussier M, Gagnon R, Brouilett M, Lalande R. Discussion of lifestyle-related issues in family practice during visits with general medical examination as the main reason for encounter: an exploratory study of content and determinants. Patient Educ Counseling. 2001;45:275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makoul G, Dhurandhar A, Goel M, Scholtens D, Rubin A. Communication about behavioral health risks: a study of videotaped encounters in 2 internal medicine practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:698–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. National ambulatory health care data. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htm Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 13.Jacobson DM, Strohecker L, Compton M, Katz DL. Physical activity counseling in the adult primary care setting: position statement of the American College of Preventive Medicine. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anis N, Lee R, Ellerbeck E, Nazir N, Greiner K, Ahluwalia J. Direct observation of physician counseling on dietary habits and exercise: Patient, physician, and office correlates. Prev Med. 2004;38:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J, Urizar G, Alehegn T, Stafford R. Diet and physical activity counseling during ambulatory care visits in the United States. Prev Med. 2004;39:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ory M, Yuma P, Hurwicz M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of doctor-geriatric patient lifestyle discussions: Analysis of ADEPT videotapes. Prev Med. 2006;43:494–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarnall K, Pollak K, Ostbye T, Krause K, Michener J. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time Allocation in Primary Care Office Visits Health Services Research. 2007;42:1871–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yawn B, Goodwin M, Zyzanski S, Stange K. Time use during acute and chronic illness visits to a family physician. Fam Pract. 2003;20:474–477. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ory MG, Jordan P, Bazzarre T. Behavioral change consortium: setting the stage for a new century of health behavior change research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:500–511. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook M. Final Report. Assessment of Doctor-Elderly Patient Encounters. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Aging; 2002. Grant No. R44 AG5737-S2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tai-Seale M, Bramson R, Drukker D, et al. Understanding primary care physicians' propensity to assess elderly patients for depression using interaction and survey data. Med Care. 2005;43:1217–1224. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000185734.00564.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware J, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36®): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teresi J, Ramiriez M, Ocepik-Weliksen K, Cook M. The development and psychometric analyses of ADEPT: an instrument for assessing the interactions between doctors and their elderly patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:225–242. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers W.H. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. StataTech Bull. 1993;13:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometics. 2000;56:645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The Merck Company Foundation. The state of aging and health in America 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/aging/saha.htm Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 29.The Alliance for Aging Research. The silver book: chronic disease and medical innovation in an aging nation. Available at: http://www.silverbook.org/SilverBook.pdf Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 30.Glasgow R, Eakin EG, Fisher E, Bacak S, Brownson R. Physician advice and support for physical activity: results from a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:189–96. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitlock E, Orleans C, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:267–284. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Resnick B, Ory M, Hora K, et al. A proposal for a new screening paradigm and tool called exercise assessment and screening for you (EASY) J Phys Activity Aging. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.2.215. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ainsworth B, Youmans C. Tools for physical activity counseling in medical practice. Obesity Res. 2002;10(suppl 1):69S–75S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Active Options for Aging Americans. Available at: http://www.activeoptions.org/ Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 35.Easy exercise and screening for you: easy screening tool. Available at: http://www.easyforyou.info/ Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 36.Learning Network for Active Aging. Available at: www.lnactiveaging.org Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 37.Browning C, Menzies D, Thomas S. Assisting health professionals to promote physical activity and exercise in people. In: Schoo A, Morris M, editors. Optimizing Physical Activity and Health in Older People. London, UK: Butterworth-Heinmann; 2004. pp. 38–62. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. One time “Welcome to Medicare” physical exam. Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/health/physicalexam.asp Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 39.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) Available at: http://web.ncqa.org/tabid/59/Default.aspx Accessed August 20, 2007.

- 40.O'Halloran J, Ng A, Britt H, Charles J. EPC encounters in Australian general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35:8–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vagholkar S, Hermiz O, Zwar N, Shortus T, Comino E, Harris M. Multidisciplinary care plans for diabetic patients: what do they contain? Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36:279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]