Abstract

Background

Drug abuse is common among adolescents and young adults. Although the consequences of intoxication are known, sequelae of drugs emerging on campuses and in clubs nationwide are not. We previously demonstrated that ketamine exposure results in lasting physiological abnormalities in mice. However, the extent to which these deficits reflect neuropathologic changes is not known.

Methods

The current study examines neuropathologic changes following sub-anesthetic ketamine administration (5 mg/kg i.p. × 5) to three inbred mouse strains. Stereologic quantification of silver stained nuclear and linear profiles as well as activated caspase-3 labeling was used to address: 1) whether or not ketamine increases excitotoxic and apoptotic cell death in hippocampal CA3 and 2) whether or not ketamine-induced cell death varies by genetic background.

Results

Ketamine increased cell death in hippocampal CA3 of adult C3H, DBA2 and FVB mice. Neither silver staining nor activated caspase-3 labeling varied by strain, nor was there an interaction between ketamine-induced cell death and strain.

Conclusions

Ketamine exposure among young adults, even in limited amounts, may lead to irreversible changes in both brain function and structure. Loss of CA3 hippocampal cells may underlie persistent ERP changes previously shown in mice and possibly contribute to lasting cognitive deficits among ketamine abusers.

Keywords: ketamine, NMDA receptor, neurotoxicity, apoptosis, drug effects, physiology

1. Introduction

NMDA antagonists are thought to produce neurotoxicity through action on several multisynaptic circuits (Farber and Olney, 2003; Noguchi et al., 2005). Although psychiatric symptoms occur following ketamine intoxication, several studies have argued that these features are less prominent than the lasting cognitive disruptions in declarative and transient memory as measured with a continuous performance task (Curran and Monaghan, 2001; Curran and Morgan, 2000; Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Lahti et al., 2001; Malhotra et al., 1997; Morgan et al., 2004; Newcomer et al., 1999; Umbricht et al., 2000; Vollenweider et al., 1997). Furthermore, Morgan et al showed chronic, repeated, recreational self-administration of ketamine also results in degradation of semantic memory as compared to ketamine naïve drug abusers (Morgan, 2005). Similarly, rodent studies suggest that chronic ketamine administration leads to long-term memory impairments and clinically relevant manifestations including decreased duration of ketamine anesthesia, development of tolerance to analgesic properties of ketamine and cross-tolerance with the effects of morphine (Fidecka, 1987; Jansen, 1990; Richebe et al., 2005). Whether recreational use of ketamine and the manifested alterations in cognitive functions and behaviors correlate with specific neuroanatomical pathophysiology is not well understood. Therefore, the current study examines the anatomical effects of ketamine exposure in mice to model the potential role of apoptotic and excitotoxic cell death in the pathophysiology of lasting cognitive impairments in ketamine abusers.

1.1. Proposed Mechanisms Of NMDA Receptor Antagonist Toxicity

Low dose ketamine induces a marked increase in glutamate release and hypermetabolism in the frontal cortex, consistent with the hypothesis that it acts preferentially to block NMDA receptors on inhibitory neurons leading to a state of disinhibition and increased glutamate release and excitotoxicity (Farber, 2003; Holcomb et al., 2005; Olney et al., 2002e). Initially, this mechanism may underlie the psychotomimetic effects observed after ketamine use (Noguchi et al., 2005). Consequently, ketamine is thought to impair learning in rodents by disrupting long-term potentiation in the hippocampus (Rowland et al., 2005). Functional MRI (fMRI) studies in healthy human volunteers reveal that intravenous infusion of sub-anesthetic doses of ketamine alters brain activity in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Changes to these regions were significantly correlated with decreases in working memory (Honey et al., 2005). Thus, it appears that alterations in hippocampus may be responsible for lasting behavioral consequences associated with NMDA receptor antagonist action.

1.2. Age and NMDA Receptor Antagonist Cell Death

The detrimental effects of ketamine, and other NMDA antagonists vary in rodents and humans at different developmental ages (Farber et al., 1995; Jevtovic-Todorovic et al., 2003; Slikker et al., 2005). Farber, Olney and colleagues, have previously demonstrated that NMDA antagonist induced neurotoxicity in retrosplenial cortex is age dependent and can be either reversible or irreversible (Farber et al., 2004; Jevtovic-Todorovic et al., 2001; Noguchi et al., 2005). Studies in rat and mouse have demonstrated that apoptotic cell death predominates in the developing CNS, while excitotoxic or other types of cell death predominate in the adult (Jevtovic-Todorovic and Carter, 2005; Wozniak et al., 1998; Young et al., 2005). It is important to note that apoptotic programmed cell death and NMDA receptor mediated excitotoxicity are fundamentally different processes with distinct time courses (Corso et al., 1997; Ishimaru et al., 1999). Regardless of the subject’s age, the dose and duration of exposure to an NMDA excitotoxin affects the ensuing pathophysiology (Creeley et al., 2006b; Olney et al., 2002c; Young et al., 2005). For example, brief exposure to ethanol causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing CNS and may contribute to fetal alcohol syndrome (Farber and Olney, 2003). In contrast, brief exposure in adult rat brain does not induce demonstrable NMDA mediated neurotoxicity in retrosplenial cortex and opposes the effects of the NMDA antagonist MK-801 (Farber et al., 2004). Other studies show that longer exposure to ethanol induces irreversible excitotoxic cerebrocortical damage in adult rodents (Collins et al., 1996; Rajgopal and Vemuri, 2002; Sultana and Babu, 2003). These age dependent reactions may also vary across brain regions because the specific excitatory inputs that contribute to pathological processes differ from region to region. Furthermore, individual cells within a specific region may undergo either apoptotic or excitotoxic cell death (Corso et al., 1997).

1.3. Rationale to Examine Hippocampal CA3

The current study directly assesses potential neuropathological consequences of ketamine exposure in hippocampal CA3 of adult mice following repeated acute ketamine administration. There are several reasons why we selected the hippocampal CA3 region for our initial studies of ketamine induced cell death. First, earlier studies showed NMDA antagonists such as ketamine, MK801, phencyclidine and memantine induced pathology to corticolimbic structures including hippocampus, thalamus, and entorhinal, retrosplenial, parietal, and cingulate cortices (Corso et al., 1997; Creeley et al., 2006a; Farber and Olney, 2003; Hansen et al., 2004; Wozniak et al., 1998). Second, cognitive deficits following ketamine abuse and/or exposure are consistent with hippocampal dysfunction. (Jarrard, 1993; McHugh et al., 2007) This has been demonstrated both in humans that display deficits in working memory (Morgan et al., 2004; Rowland et al., 2005) as well as rodents using radial arm and water maze tasks or contextual fear conditioning (Jevtovic-Todorovic et al., 2003; Stiedl et al., 2000; Wozniak et al., 1996; Young et al., 1994). The cognitive deficits observed after ketamine abuse have also been directly related to disruptions of NMDA receptors within the CA3 region of hippocampus that are essential to the early stages of learning(Nakazawa et al., 2004; Nakazawa et al., 2003). Additionally, the previous data from our group that demonstrated lasting deficits in Event Related Potentials (ERPs) following ketamine exposure in mice were recorded from CA3, suggesting that this region may be vulnerable to ketamine induced changes (Maxwell et al., 2006). It is, however, important to note that we are not hypothesizing that the effects of ketamine are specific for CA3 alone, but rather that excitotoxic and or apoptotic degenerative processes being examined in the current study may be representative of similar changes in other regions. Therefore, stereological methods were employed to quantify the number of dead or dying cells in this NMDA receptor rich region (Siegel et al., 1994).

1.4. Possible Genetic Differences in Vulnerability to Ketamine

A second aim of the current study was to elucidate whether genetic background altered cytotoxic cell death in the brain following ketamine exposure. MK801 was previously found to have differential effects on cerebrocortical neuronal injury in C57BL/6J, NSA and ICR mice (Brosnan-Watters et al., 2000). Additionally, earlier studies from our group indicated that the acute effects of ketamine on auditory ERPs vary among inbred strains, suggesting that there may be genetic heterogeneity for the consequences of ketamine abuse in humans. We also found persistent changes in ERPs following cessation of chronic ketamine exposure in adult mice, supporting that ketamine abuse may lead to irreversible changes in brain function (Maxwell et al., 2006). However, the mediators of such persistent changes are not known. Several groups have previously shown that NMDA antagonist exposure during development leads to both cortical and subcortical apoptotic cell death, suggesting that cell loss may underlie lasting ERP deficits (Corso et al., 1997; Creeley et al., 2006a; Farber and Olney, 2003; Hansen et al., 2004; Olney et al., 2002d; Rudin et al., 2005; Wang and Johnson, 2007; Wozniak et al., 1998). This evidence leads to the hypothesis that some individuals may be genetically more vulnerable to physiological effects of ketamine than others. It follows that genetic variance within humans or mouse strains may affect vulnerability to ketamine-induced cell death. Here, we test that hypothesis using inbred mouse strains that display variance for the acute effects of ketamine on event related potentials.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.1.1. Husbandry

A total of 46 male mice from three inbred strains (C3H/HeHsd n = 14, DBA/2Hsd n = 16, and FVB/Hsd n = 16) were obtained from Harlan (Sprague Dawley, IN). The mice were group housed and had free access to food and water. They acclimated for at least one week prior to the experiment in a vivarium that was temperature controlled and had light dark cycles alternating every 12 hours. Mice were 8-10 weeks of age at the time of treatment. All protocols were conducted in accordance with University Laboratory Animal Resources guidelines and are approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1.2. Treatment Conditions

Mice (N = 7 or 8 for each group) were injected i.p. once every 30 minutes for a total of 5 doses with either ketamine (5 mg/kg) or physiological saline and returned to their home cages. The serum half-life of ketamine is approximately 3 hours in humans, as compared to 13 minutes in mice (Maxwell et al., 2006; McLean et al., 1996). Therefore, this low dose paradigm was chosen to better mimic recreational use by administering ketamine approximately once every two half lives. Mice were observed between administrations to confirm the lack of anesthetic effects and monitor behaviors. Two hours after the last dose (4 hrs after initial dose), mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital/xylazine (60/5 mg/kg), and were transcardially perfused with 4°C saline (1 min at 9 ml/min flow rate) followed by fixation solution (4 min at 9ml/min) consisting of 0.07M cacodylate buffer, 4.0% sucrose, and 10% formalin, PH = 7.4.

We sacrificed animals in the current study at a time point that could be sensitive to both excitotoxic and apoptotic cell death. Previous studies reported reliable silver labeling of neurodegeneration in hippocampus at time points as early as 1-4 hrs after proton beam irradiation, electric shock, or ibotenic acid injection (both in injured and contralateral hemispheres) (Brisman et al., 2005; Ishida et al., 2004; Zsombok et al., 2005). Our own preliminary experiments in ketamine treated and saline treated mice (total n = 20, two mice per drug condition at each of 5 time points) detected qualitative differences in silver labeling at 2, 7, 12, 21, and 72 hours after treatment. Pilot stereological quantification in one mouse from each drug condition at each of the 5 time points determined that the de Olmos method labeled more cells in ketamine treated than saline treated mice across all time points. Furthermore, the patterns of labeling at 21 hours was similar to previously published data (Farber and Olney, 2003; Olney et al., 2002b; Olney et al., 2002c). Silver techniques identify cells that are degenerating due to a variety of cellular mechanisms and cannot definitively distinguish excitotoxic from apoptotic cell death (Farber and Olney, 2003; Gallyas et al., 2002). Therefore, we also employed activated caspase-3 immunolabeling to discriminate cells committed to apoptosis (Olney et al., 2002a; Young et al., 2005). Hence we chose to sacrifice the mice 2 hours after the last dose of ketamine (4 hours after the first dose) so as to be able to capture both excitotoxic and apoptotic processes.

2.1.3. Preparation of Brain Tissue

Brains were left in the skull for 48 hours at 4°C in the fixation solution. Once harvested, the brains were cryoprotected through increasing sucrose solutions (10%, 20%, 30% sucrose in cacodylate buffer, 4°C, until they sank). Each brain was frozen rapidly on dry ice. After 15 minutes (min) on dry ice, brains were wrapped in plastic wrap and aluminum foil for storage at -80°C until they were embedded into gelatin blocks (gelatin/30% sucrose/glycerol). Blocks of 4 brains containing at least one brain from each strain and condition were made, fixed and cryoprotected. Blocks were marked with dye and the right lower brain was oriented 180° from the others to ensure location of each brain could be identified. The individual making the blocks, performing staining assays and stereological analyses was blinded to mouse strain and treatment condition. Once mounted over dry ice, the blocks equilibrated to -20°C and sections were cut using a cryostat at 45μm. The sections were collected serially and put into cryoprotectant (polyethylene glycol/glycerol/sucrose/pvp) or cacodylate buffer over ice yielding 4 sets (A, B, C, D) of every 4th section. A random number generator (Stereo Investigator v6, MicroBrightfield, Inc) was used to determine which sets of every 4th section would be used for assays and subsequently for stereological quantification studies.

2.2. Assays

2.2.1. Silver Staining

Set B of free floating sections was assayed for neurodegeneration using the de Olmos Amino-Cupric-Silver method (DeOlmos and Ingram, 1971). This technique is sensitive to detecting apoptotic and other neuronal cell death processes (Noguchi et al., 2005). The heating method during the pre-impregnation step was modified to better control temperature and decrease background staining. Specifically, sections (10 per 50 ml of pre-impregnation solution) were heated in 2 beakers at a time to 45-47°C in a microwave (Goldstar intellowave, 1100W) with a turntable at 20% power. Beakers were then covered in para-film and put in a 50°C water bath for 15 min. All beakers contained at least one positive control section prepared from a deeply anesthetized mouse that underwent traumatic brain injury using steel electrode wire (Davies et al., 1996; de Olmos et al., 1994; Flores et al., 2005). Mice for positive controls remained alive while anesthetized for 2 hrs and then were sacrificed during perfusion as previously described. Covered beakers were then transferred and allowed to cool to room temperature before proceeding with the assay as described by J. De Olmos. The sections were then mounted in rostral to caudal order in 0.05 M Trizma Base onto freshly gelatinized subbed slides and allowed to dry overnight at 25°C. Sections were rehydrated through decreasing ethanol solutions (100,100, 95, 85, 75%, dH20), Nissl stained in Neutral Red, dehydrated through increasing % ethanol, cleared in citrisolve 2×10 min, and coverslipped using cytoseal 60 (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) mounting medium. Ordering of the sections from rostral-caudal was then confirmed under low power on a microscope (Figure 1).

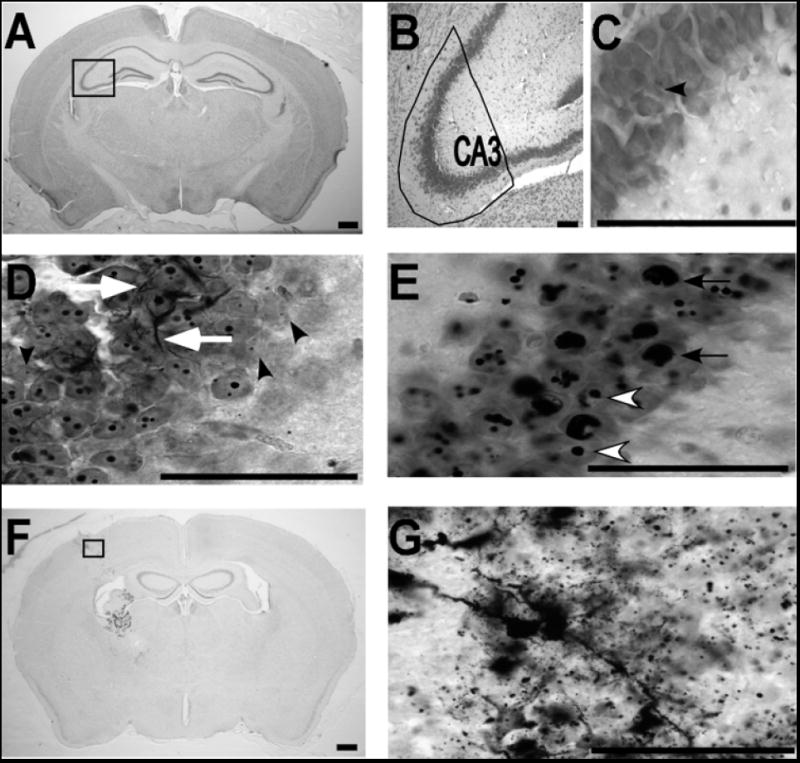

Figure 1. Mouse brain sections labeled for neurodegeneration with silver method.

A) Low power micrograph of a saline treated mouse (1.6x) is shown with the CA3 region indicated with a rectangular box. B) The CA3 hippocampal region outlined in A is shown at higher power (10X). C) A high magnification (100X) micrograph of the pyramidal cell layer in CA3 from outlined area in A is shown to reveal cellular morphology in the control condition. The black arrowhead shows one silver profile (punctate) in this field. D) The CA3 region in a ketamine treated mouse is shown at high power (100X). Black arrowheads show examples of punctate nuclear profile-1 (less than or equal to 0.8μm). White arrows indicate examples of linear profiles. E) White arrowheads indicate examples of silver positive nuclear profile-2 (diameter between 0.8 and 2.5μm) and black arrows indicate pyknotic-like profile-3 (diameter greater than 2.5μm) in a ketamine treated mouse. F & G) Micrographs show examples from a positive control mouse with silver staining at the lesion site at 1.6x (F) and 100x (G). Scale bars = 50μm in all panels.

2.2.2. Activated Caspase-3 Immunostaining

Because the silver method described above can not distinguish excitotoxic from apoptotic cell death, we also utilized immunolabeling for activated caspase-3. This method was intended to determine if a subset of cells identified with silver labeling were subject to apoptotic cell death. Cleaved Caspase-3 at Asp175 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) immunoreactivity was examined to evaluate acute cell death via the apoptotic pathway. Set C of every 4th section was allowed to thaw to room temperature. In addition, positive control sections were included and processed along side experimental sections. Cryoprotectant was poured off followed by addition of distilled water for 5 minutes. Washing was repeated 3 × 5 min. Sections were then floated onto slides in 0.1M sodium acetate, PH = 6.0, buffer and allowed to dry at room temperature overnight. Antigen unmasking was accomplished by heating and maintaining the specimen slides at 95°C for 3 minutes in a 0.01M sodium citrate, PH = 6.0, bath. Slides remained in the bath and cooled for 20 min at 25°C. Following antigen unmasking, sections were transferred to dH2O (2 × 3 min) and then to 0.1M phosphate buffered saline, PH = 7.4 and 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T; 1 X 3 min). Subsequently, endogenous peroxidases were quenched for 45 min in 6% hydrogen peroxide in methanol, followed by 3 washes in PBS-T. Non-specific binding was blocked in 5% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 diluted in PBS (NGS) for 1 hour. Primary antibody (1:500 in NGS) incubation was done at 4°C for 2 days (humidified chamber, shaking 30 rpm). Following incubation with primary antibody, sections were washed in PBS-T 3 × 3 min and blocked in NGS. The secondary antibody used was EnVision + Dual Link System peroxidase (DAKOCytomation, Carpinteria, CA). Specimens were then washed as before and visualized in 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Counterstaining was done in hematoxylin and eosin before sections were dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped as specified earlier (Figure 2).

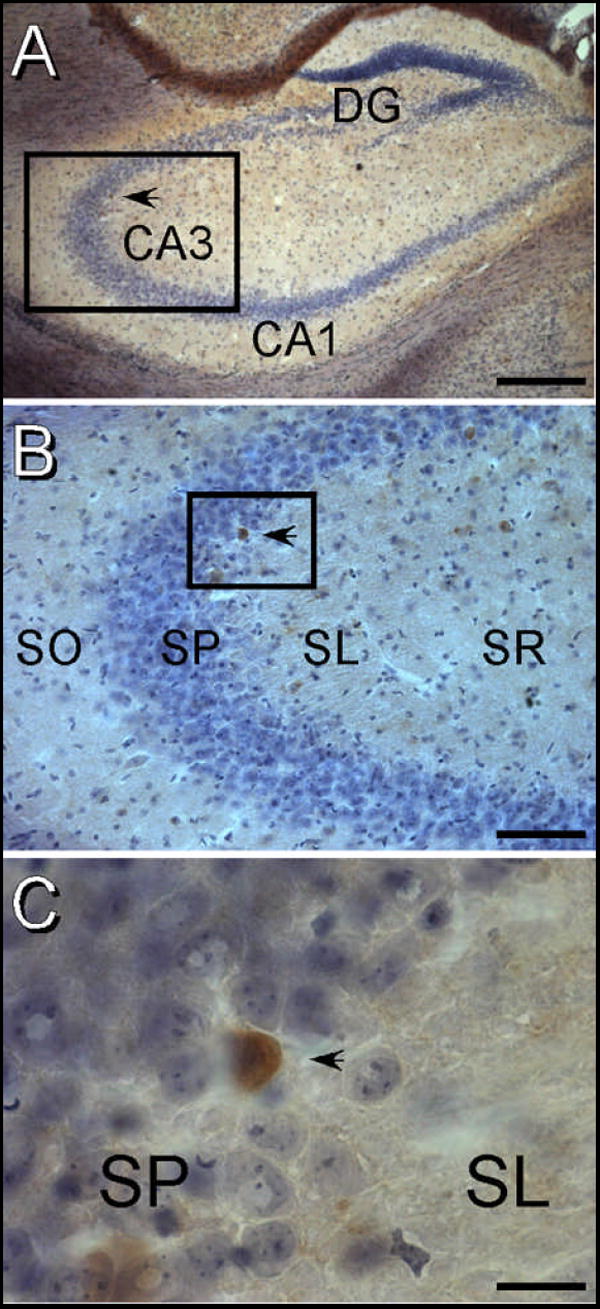

Figure 2. Activated Caspase-3 labeling in a ketamine treated mouse.

Black arrowheads indicate the same activated caspase-3 labeled cell in the CA3 pyramidal cell layer. A) 4x micrograph of the hippocampal formation. The boxed region identifies the CA3 region that is shown in panel B. B) 20x micrograph of CA3 showing the laminar location of a caspase-3 labeled cell in the pyramidal cell region. The boxed region is shown at higher magnification in panel C. C) 100x micrograph of an activated caspase-3 labeled cell. Immunolabeling is visualized in a brown DAB precipitate which is shown in the context of a light Hematoxylin/Eosin counterstain. Note that the immunopositive cell is in the stratum pyramidale at the junction of Stratum lucidum in CA3. Abbreviations: DG – Dentate Gyrus, CA1 – CA1 Region of hippocampus, CA3 – CA3 region of hippocampus, SL – Stratum Lucidum, SO – Stratum Oriens, SP – Stratum Pyramidale, SR – Stratum Radiatum. The scale bar = 500 μm in panel A, 100 μm in panel B and 20 μm in panel C.

2.3. Stereological Quantification

Principles of stereology were closely followed to ensure unbiased population estimates (Glaser and Glaser, 2000; Gundersen et al., 1988; West, 1993). To decrease processing bias, the brain blocks were randomly cut at a 3 mm region where the cortex meets the cerebellum. Ethanol solutions were freshly prepared and timing was closely monitored to reduce shrinkage effects (shrinkage of 43%, optimal less than 50%) and maintain consistent section thicknesses (Dorph-Petersen et al., 2001; Gardella et al., 2003). In order to generate average weighted population estimates, each sampling site was measured for thickness.

The region of interest (ROI) was defined as Bregma -0.94mm through Bregma -2.46mm in the anterior-posterior direction as determined at 4x power. ROIs including CA3 were traced in Stereo Investigator at 4x. CA3 was defined as the region including all layers of the hippocampus between the beginning and end of the stratum lucidum. Boundaries were delineated using a stereotaxic mouse atlas and by observing cellular morphology at higher power (Paxinos and Franklin, 1997).

2.3.1. Optical Fractionator Method

A pilot counting study was done to optimize the optical fractionator parameters implemented and identify morphology of specific staining. Coefficients of Error (CE) for biological and methodological variance were analyzed to determine the section interval that would provide adequate sampling in CA3 of hippocampus (Cruz-Orive and Weibel, 1981; Gundersen and Osterby, 1981; West, 1999). Counting was done with a 100x oil objective on a Nikon E800 microscope. Nuclei were counted when the nucleus of the cell being evaluated first came into focus was within or touching inclusion lines of the optical disector. In the z direction, cells at the very top of the disector were not included in the estimates (West, 1993).

2.3.1.1. Silver Positive Nuclear Profiles

The optical fractionator method was used to count three silver-positive nuclear profiles that exhibited specific staining and were consistent with morphologies presented in previous studies using silver (Adams et al., 2004; de Olmos et al., 1994; Wozniak et al., 1998). Profile diameters were directly measured at 100x with the computer assisted program, and subsequently binned based on the total nuclear staining for an individual cell. Profile-1 was small and punctate having total diameters less than or equal to 0.8μm; Profile-2 was medium in size, having diameters between 0.8μm and 2.5 μm; Profile-3 was large and pyknotic-like, having diameters greater than 2.5μm. The counting frame size was 25μm × 25μm, the grid size was 200μm × 200μm, and the optical disector height was 14μm with 2μm guard zones.

2.3.1.2. Activated Caspase-3 Profiles

The sampling scheme for apoptotic profiles used a 50μm2 counting frame and 225μm2 grid size. The optical disector parameters were consistent with those of the silver counting study, and nuclei of brain cells exhibiting specific DAB visualized labeling were counted only if they met inclusion criteria described earlier. Morphology of these cells was consistent with examples shown in previous studies (Nakajima et al., 2000; Rothstein and Levison, 2005).

2.3.2. Estimation of Silver Positive Linear Profiles

Principals of designed based stereology indicate that the estimator will be unbiased if, and only if, the interactions between the sampling probe and structure of interest are isotropic (Larsen et al., 1998). Since the surface of a sphere is by definition isotropic, having planar surfaces with all integral angles in 3-dimensional space, any interaction with a linear profile will be isotropic regardless of the orientation of the fiber (Mouton et al., 2002). Therefore the spherical probe Space Balls was chosen in Stereo Investigator. The diameter of the spheres used in the systematic random sampling scheme was 14μm, the grid size was 225μm2. While focusing through the z-axis of each sampling site, any intersection of the silver stained fibers with the sphere was recorded.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.4.1. Factorial ANOVA

There were a total of five profiles quantified. These included silver staining of nuclear profiles 1, 2, 3, and of linear profiles as well as DAB labeling of activated caspase-3 immunocytochemistry. Each individual profile in addition to total nuclear silver counts were analyzed independently using a Factorial ANOVA (Statistica, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK) for main effects of strain and ketamine as well as the interaction of these factors. Significant interactions were followed with post hoc analyses.

2.4.2. Correlation of silver positive profiles with activated caspase-3 labeling

Correlation analyses were performed between activated caspase-3 and each of the nuclear markers with silver labeling as well as for total nuclear markers and fiber length (Statistica). These analyses were performed to determine whether or not any of the silver labeled profiles (nuclear markers 1, 2 or 3 and total fiber length) identified a similar pattern of cell death as activated caspase-3. These data were then interpreted as a means to estimate the proportion of cells that were likely to be undergoing apoptotic cell death under the conditions tested.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Observations

Five sub-anesthetic doses of ketamine (5 mg/Kg) were administered over 2 hours in three strains of adult mice to model recreational use of ketamine. Qualitative observations were made at time of injections and throughout the inter-injection intervals. Five minutes following the first and second doses, mice were awake and calm compared to saline treated controls. By 10 min, ketamine treated mice displayed mild ataxia and by 25 min were attempting to ambulate more. At approximately 20 minutes after the 3rd through 5th doses, ketamine treated mice displayed increased grooming and respiration (180 breaths per minute) as compared to controls (84 breaths minute).

3.2. Stereology Measures

Systematic Random Sampling (SRS) via the Optical Fractionator Method was done on every 4th section in 46 mice. The mean mounted section thickness across all mice in the study was empirically determined to be 25.7μm. Total population estimates for each of the profiles counted in hippocampal CA3 were quantified for each mouse in Stereo Investigator using the number weighted section thicknesses for the SRS done in that mouse. Similarly the total length of non-nuclear silver stained profiles was estimated based on the Space Balls probes run in each mouse (Figure 3).

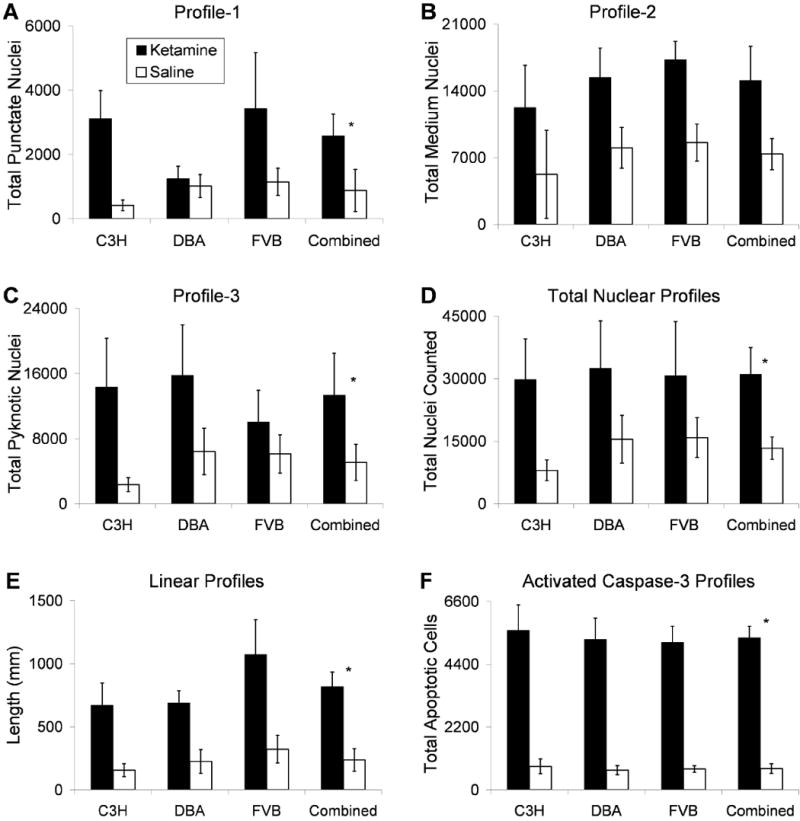

Figure 3. Ketamine increases silver stained profiles in mouse hippocampal CA3 region.

Each bar graph reflects Optical Fractionators stereological estimates for total number of specified nuclear profiles counted in murine CA3 hippocampus, weighted for empirically measured section thicknesses. Quantification was done in every fourth section (25.7μm average thickness across all mice) of C3H/HeHsd, DBA/2Hsd and FVB/Hsd mice (n = 7 or 8) that were treated 5 times with either ketamine 5 mg/kg (black bars) or normal saline (white bars) over two hours. A-C show estimates for neuronal nuclei containing: A) Profile-1, punctate labeling, diameter less than or equal to 0.8μm diameter; B) Profile-2, diameter between 0.8 and 2.5μm; C) Profile-3, pyknotic like labeling diameter greater than 2.5μm. D) The total number of degenerating nuclear profiles counted for each condition and strain are displayed. E) Length of silver labeled linear profiles. F) Population estimates of apoptotic profiles as visualized with immunocytochemistry for activated caspase-3. Analyses did not indicate a main effect of strain, therefore the final columns in each panel displays combined data of all three strains (n = 23 for ketamine, n = 23 for saline). * Note that for profile-1 (punctate), profile-3 (pyknotic), total nuclear, linear, and apoptotic profiles (A, C-E), the ANOVA revealed a main effect of ketamine treatment (p ≤ 0.02). Profile-2 (B) displayed a non-significant trend for increased labeling with ketamine (p = 0.059). Error bars depict Standard Error of the Mean for each group.

3.3. Statistical Analyses

The Factorial ANOVA revealed that ketamine treated mice had significantly increased silver staining for profiles 1, 3, total nuclear and linear profiles as well as activated caspase-3 profiles across the three mouse strains tested (C3H, DBA, FVB; n=7 or 8 each group) (Figure 3 and Table 1). There was no main effect of ketamine on profile 2 alone. Additionally, there was no effect of strain or interaction between strain and ketamine conditions for any profile alone or their combination. These data indicate that ketamine causes increased cell death in hippocampal CA3 which did not vary with genetic background.

Table 1.

Ketamine increases silver-positive nuclear and linear profiles as well as activated caspase-3 labeled cells in the hippocampal CA3 region of C3H, DBA and FVB mice.

| Variable | Df | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profile 1 (diameter less than or equal to 0.8μm) | |||

| Strain | 2 | 0.935 | 0.401 |

| Condition | 1 | 6.053 | 0.018* |

| Strain by condition | 2 | 1.180 | 0.318 |

| Profile 2 (diameter between 0.8 and 2.5μm) | |||

| Strain | 2 | 0.353 | 0.705 |

| Condition | 1 | 3.539 | 0.067 |

| Strain by condition | 2 | 0.015 | 0.985 |

| Profile 3 (diameter greater than 2.5μm) | |||

| Strain | 2 | 0.333 | 0.719 |

| Condition | 1 | 6.116 | 0.018* |

| Strain by condition | 2 | 0.487 | 0.618 |

| Total Nuclear Profiles | |||

| Strain | 2 | 0.185 | 0.832 |

| Condition | 1 | 6.063 | 0.018* |

| Strain by condition | 2 | 0.075 | 0.928 |

| Total Linear Profiles | |||

| Strain | 2 | 1.95341 | 0.155 |

| Condition | 1 | 20.50795 | 0.000* |

| Strain by condition | 2 | 0.49721 | 0.612 |

| Activated Caspase-3 Profiles | |||

| Strain | 2 | 0.1279 | 0.880 |

| Condition | 1 | 110.9984 | 0.000* |

| Strain by condition | 2 | 0.0452 | 0.956 |

denotes p < 0.05

3.4. Correlation Analyses

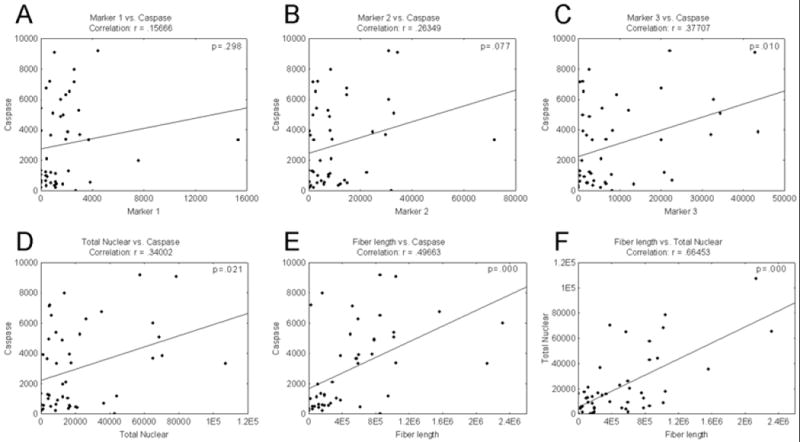

Correlation analyses were performed between activated caspase-3 and each of the nuclear markers with silver labeling as well as for total nuclear markers and fiber length (Figure 4). Data indicate that there are significant correlations between nuclear marker 3 and caspase-3 (p = 0.010), total nuclear labeling and caspase-3 (p = 0.021), and fiber length and caspase-3 (p < 0.001). Note that total nuclear labeling with silver is also significantly correlated with total silver labeled fiber length (p < 0.001), suggesting that labeling in cell bodies is sensitive to the same processes causing fiber labeling. The observation that markers 1 and 2 are not significantly correlated with caspase-3 may indicate that these profiles are either more reflective of excitotoxic processes, or are labeling cells in a stage of the apoptotic cascade that does not express activated caspase-3.

Figure 4. Correlation of silver positive profiles with activated casepase-3 labeling.

Correlation plots between activated caspase-3 and silver labeling for A) nuclear markers 1, B) marker 2 and C) marker 3 as well as D) total nuclear labeling and E) silver labeled fiber length are shown. These correlation analyses indicate significant correlations between marker 3 and caspase-3 (p = 0.010), total nuclear labeling and caspase-3 (p = 0.021), and fiber length and caspase-3 (p = 0.000). F) Note that total nuclear labeling is significantly correlated with fiber length (p = 0.000), suggesting that the pattern of labeling in cell bodies is sensitive to the same processes causing fiber labeling. The observation that markers 1 and 2 are not significantly correlated with caspase-3 may indicate that these profiles are either more reflective of excitotoxic processes, or are labeling cells in a stage of the apoptotic cascade that does not express activated caspase-3.

3.5. Histogram Analysis

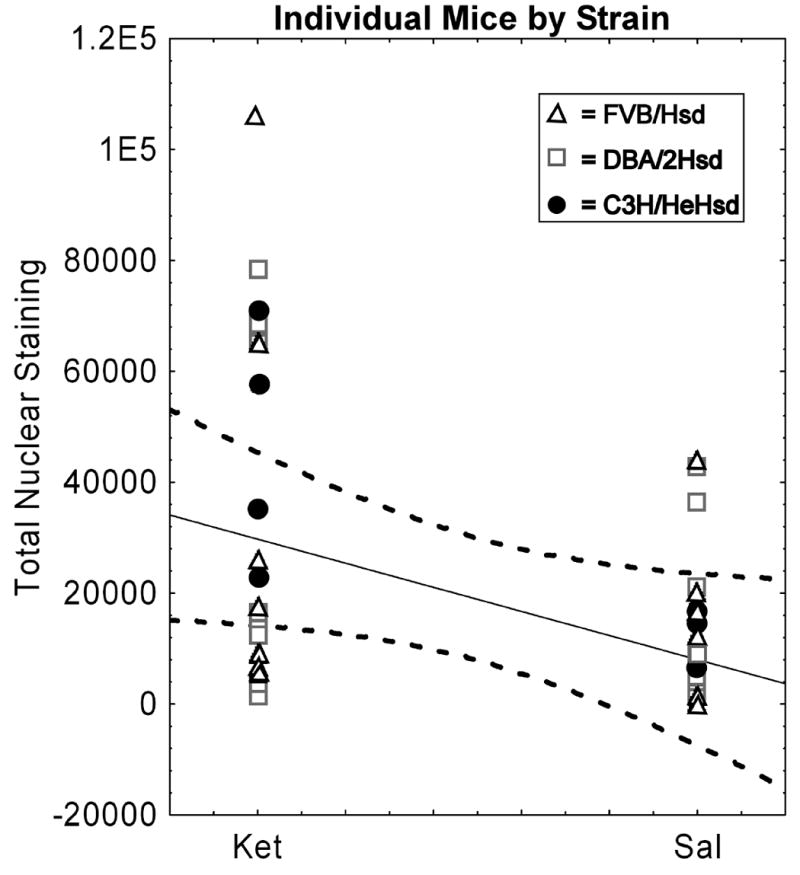

Scatter plots of total nuclear staining supported that ketamine had a similar neurotoxic main effect in CA3 hippocampus of all 3 strains evaluated. Each strain was represented in outlier and main groups (within 95% confidence interval) for silver labeled cell counts in mice receiving ketamine without a significant interaction between strain and treatment conditions (Figure 5, Table 1). Interestingly, scatter plots for each profile alone also revealed outlier groups that had at least twice the number of silver stained cells. Our findings suggest that environmental factors may contribute to individual vulnerability to the neurotoxic effects of ketamine.

Figure 5. Total Nuclear Staining in CA3 hippocampus as a function of Drug Condition.

Graphs represent individual mice from the three strains tested that differ in genetic background. Mice received either five i.p. injections of ketamine (5 mg/kg) or saline. Dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval for distribution. Note that all strains are represented in the sub-population of mice shown to have significantly increased nuclear profiles following ketamine (p < 0.018, for all mice by condition).

4. Discussion

Previous studies of NMDA antagonists such as ketamine, phencyclidine and MK801 have concentrated on the detrimental effects of these agents on developing brain in juvenile rodents. Our current study in 8-10 week old mice indicates that exposure to even a low dose of ketamine induces quantifiable morphological changes in the brains of mice that are comparable in development to young human adults (Farber et al., 1995). Considering that the largest proportion of ketamine abusers are teenagers and young adults (ages 16-23), it is important to know if there are lasting neurotoxic (excitotoxic or apoptotic) effects beyond the early developmental period. The risk to adolescents and young adults may increase if abusers have the subjective perception that ketamine is safe or combine it with other drugs of abuse. In fact, a recent study of club drug use prevalence found that 85% of ketamine abusers also used other drugs (Wu et al., 2006). These findings have important implications as data by Morgan and colleagues demonstrated acute and lasting cognitive deficits among multiple drug users between the ages of 18-35 are heightened when ketamine is also abused (Morgan, 2005).

Ketamine intoxication in humans leads to cognitive difficulties that may persist for several days or more following recreational use (Curran and Monaghan, 2001; Curran and Morgan, 2000; Javitt and Zukin, 1991; Lahti et al., 1995; Newcomer et al., 1999; Vollenweider et al., 1997). Additionally, we previously demonstrated that electrophysiological function remains abnormal in mice for at least one week after cessation of daily ketamine administration (Maxwell et al., 2006). Such lasting alterations in human behavior and murine physiology could result from alterations in the number of cells that participate in complex circuits and/or persistent alterations in function, expression and interactions of subcellular machinery. Previous studies demonstrate that NMDA antagonists cause apoptosis and excitotoxic cell death in neurons (Farber and Olney, 2003; Hayashi et al., 2002; Olney, 2002). Similarly, the current study showed increased number of silver positive nuclear and axonal/dendritic profiles in hippocampal CA3 following brief repeated ketamine administration in mice. Previous studies indicate that reduction of NMDA receptor function for only a few hours during early development can trigger neurodegeneration and disrupt somatosensory relay neurons later in life (Adams et al., 2004; Hansen et al., 2004). These data suggest that NMDA receptors may play a role in cell survival (de Rivero Vaccari et al., 2006; Ikonomidou et al., 1999). Thus, direct loss of a small set of brain cells and their processes could result in accelerated death of other cells over time, resulting in increasing divergence in surviving cell number. Furthermore, apoptosis is a very rapid event limiting the ability to capture all effected cells at a single cross sectional time point (Simonati et al., 2003). Therefore, an apparent loss of a small number of cells may represent only a subset of more widespread apoptosis.

The impact of external stressors on individuals exposed to ketamine is another consideration regarding mediators of cellular pathology. Our group’s earlier ERP studies found that the response to ketamine varied by strain after a single acute injection. In contrast, chronic daily administration of ketamine resulted in similar lasting changes in ERPs regardless of the extent of acute changes. This dosing paradigm revealed a sub-population of mice that were distinctly more affected by ketamine than the remainder. This group of vulnerable mice contained representatives from all three strains evaluated (Figure 3). We postulate that stress may contribute to these differential responses following ketamine exposure. Supporting data across various species shows that environmental stressors can induce lasting changes in hippocampus. For example, handling-induced stress in rats and guinea pigs causes hippocampal cell loss and spatial memory impairments through a mechanism of adrenal steroid secretion (Meaney et al., 1991; Stein-Behrens et al., 1994). Additionally, direct (implantation of a corticosteroid pellet) and indirect (social deprivation) stress in prepubescent and adult primates was found to increase degeneration of CA3 neurons and permanently alter dentate gyrus granule cells that project into the CA3 region (McHugh et al., 2007; Sapolsky et al., 1990; Siegel et al., 1993). Therefore, lasting morphological changes in hippocampus may render these sub-populations especially vulnerable to the neuropathologic effects of ketamine that are separate from genetic background. Future studies are needed to further parse the contributions of genetic and environmental factors like stress or drug use habits that determine the extent of ketamine neurotoxicity.

Loss of CA3 hippocampal cells in the present study also implies possible alterations of input to and output from excitatory synapses in the CA3 region. This type of diminished neurotransmission has been shown to compromise NMDA-dependent synaptic plasticity, which may affect learning and memory (Rajji et al., 2006; Rowland et al., 2005). Furthermore, studies of head trauma in adult mice suggest that initial loss of a small number of cells can lead to subsequent cell loss in efferent target regions (Tashlykov et al., 2007). NMDA receptor function also plays a key role in modulating GABAergic interneurons and maintaining tonic inhibition over excitatory inputs to primary neurons in corticolimbic brain regions (Koliatsos et al., 2004). Therefore, NMDA receptor mediated glutamate hypofunction induced by ketamine may decrease this GABAergic inhibition, thereby releasing excessive excitatory activity as the putative proximal mechanism of injury to corticolimbic regions. Thus, reduced excitation of NMDA receptors can produce specific forms of memory dysfunction that may contribute to lasting cognitive difficulties observed following ketamine use (Farber, 2003).

Data in the current study demonstrate that there were more silver positive cells than those labeled with activated caspase-3. There are a number of possible reasons for this observation. This difference may occur because silver staining identifies cells with both apoptotic and excitotoxic cell death and because activated casepase-3 immunolabeling will only identify the subset of cells that express the antigen at the time that the animal was sacrificed (Simonati et al., 2003). Therefore, an apparent loss of a small number of cells with activated caspase-3 immunolabeling may represent only a subset of more widespread apoptosis. Alternatively, silver staining will identify cells at various stages of cell death, suggesting that the total number of silver positive profiles may be a better metric of total cellular damage from both excitotoxic and apoptotic mechanisms (Farber and Olney, 2003; Olney et al., 2002a; Young et al., 2005).

In addition to lasting cognitive disruptions in memory, it is important to note that recent studies suggest possible therapeutic uses of ketamine in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. A recent study by Zarate and colleagues at the National Institutes of Health indicates that ketamine is a robust, rapid and effective anti-depressant (Zarate et al., 2006). Similarly, a pilot clinical trial demonstrates that low dose ketamine infusion is associated with substantial decreases in depressive symptoms approximately three days after exposure when compared to placebo (Berman et al., 2000). Ketamine has also been shown to improve the postoperative mood of depressed patients when used as both an adjunctive and inductive dose in surgery (Kudoh et al., 2002). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that modulation of NMDA-mediated glutamate transmission may be contributory to the pathophysiology of depression and conversely may account for an important mechanism of ketamine’s mood-enhancing action (Ostroff et al., 2005). However, our data suggest that the clinical benefits of ketamine as an antidepressant may need to be balanced with its potential for abuse and ability to produce lasting neuropathological changes.

A limitation of this study is that it restricted analysis to one brain region. Literature supports the hypothesis that ketamine differentially affects other cortical and subcortical brain regions that contribute to ERPs and other behavioral effects (Duncan et al., 2001; Duncan et al., 1999). Future quantitative studies in other affected brain regions could reveal genetically mediated strain differences in neurotoxic effects of ketamine. Additionally, even if strain differences were apparent, cell death due to ketamine among humans in real world situations may not be dominated by genetic background as much as other factors including stress, comorbid alcohol and drug abuse, or other physical differences. The current study demonstrates that ketamine exposure in adult animals leads to neuropathological processes in CA3 hippocampus and suggests that lasting disability following ketamine abuse may be due, in part, to cell death. Future studies will expand upon this work to examine other brain regions, and interactions with stress.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NIH/NIDA 1R21DA017082-01 and NIH/NIMH P50 MH064045. The funding agencies had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest CMT and CRR have no potential conflicts of interest. SJS has no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the content of the current manuscript and study. SJS has received grant support, unrelated to these studies from Eli Lily, AstraZeneca, NuPathe, NARSAD and The Stanley Medical Research Institute. SJS has served as a consultant to Pfizer, NuPathe, and Sanofi-Aventis and the CME Institute. None of the authors own any shares in any pharma company.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams SM, de Rivero Vaccari JC, Corriveau RA. Pronounced cell death in the absence of NMDA receptors in the developing somatosensory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9441–9450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3290-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisman JL, Cosgrove GR, Thornton AF, Beer T, Bradley-Moore M, Shay CT, Hedley-Whyte ET, Cole AJ. Hyperacute neuropathological findings after proton beam radiosurgery of the rat hippocampus. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1330–1337. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000159885.34134.20. discussion 1337-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan-Watters G, Ogimi T, Ford D, Tatekawa L, Gilliam D, Bilsky EJ, Nash D. Differential effects of MK-801 on cerebrocortical neuronal injury in C57BL/6J, NSA, and ICR mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24:925–938. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(00)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Corso TD, Neafsey EJ. Neuronal degeneration in rat cerebrocortical and olfactory regions during subchronic “binge” intoxication with ethanol: possible explanation for olfactory deficits in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:284–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso TD, Sesma MA, Tenkova TI, Der TC, Wozniak DF, Farber NB, Olney JW. Multifocal brain damage induced by phencyclidine is augmented by pilocarpine. Brain Res. 1997;752:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creeley C, Wozniak DF, Labruyere J, Taylor GT, Olney JW. Low doses of memantine disrupt memory in adult rats. J Neurosci. 2006a;26:3923–3932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4883-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creeley CE, Wozniak DF, Nardi A, Farber NB, Olney JW. Donepezil markedly potentiates memantine neurotoxicity in the adult rat brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2006b doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Orive LM, Weibel ER. Sampling designs for stereology. J Microsc. 1981;122:235–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1981.tb01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran HV, Monaghan L. In and out of the K-hole: a comparison of the acute and residual effects of ketamine in frequent and infrequent ketamine users. Addiction. 2001;96:749–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96574910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran HV, Morgan C. Cognitive, dissociative and psychotogenic effects of ketamine in recreational users on the night of drug use and 3 days later. Addiction. 2000;95:575–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, Field PM, Raisman G. Regeneration of cut adult axons fails even in the presence of continuous aligned glial pathways. Exp Neurol. 1996;142:203–216. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Olmos JS, Beltramino CA, de Olmos de Lorenzo S. Use of an amino-cupric-silver technique for the detection of early and semiacute neuronal degeneration caused by neurotoxicants, hypoxia, and physical trauma. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1994;16:545–561. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JC, Casey GP, Aleem S, Park WM, Corriveau RA. NMDA receptors promote survival in somatosensory relay nuclei by inhibiting Bax-dependent developmental cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16971–16976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608068103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeOlmos JS, Ingram WR. An improved cupric-silver method for impregnation of axonal and terminal degeneration. Brain Res. 1971;33:523–529. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorph-Petersen KA, Nyengaard JR, Gundersen HJ. Tissue shrinkage and unbiased stereological estimation of particle number and size. J Microsc. 2001;204:232–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2001.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan EJ, Madonick SH, Parwani A, Angrist B, Rajan R, Chakravorty S, Efferen TR, Szilagyi S, Stephanides M, Chappell PB, Gonzenbach S, Ko GN, Rotrosen JP. Clinical and sensorimotor gating effects of ketamine in normals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:72–83. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GE, Miyamoto S, Leipzig JN, Lieberman JA. Comparison of brain metabolic activity patterns induced by ketamine, MK-801 and amphetamine in rats: support for NMDA receptor involvement in responses to subanesthetic dose of ketamine. Brain Res. 1999;843:171–183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber NB. The NMDA receptor hypofunction model of psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:119–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber NB, Heinkel C, Dribben WH, Nemmers B, Jiang X. In the adult CNS, ethanol prevents rather than produces NMDA antagonist-induced neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 2004;1028:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber NB, Olney JW. Drugs of abuse that cause developing neurons to commit suicide. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;147:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber NB, Wozniak DF, Price MT, Labruyere J, Huss J, St Peter H, Olney JW. Age-specific neurotoxicity in the rat associated with NMDA receptor blockade: potential relevance to schizophrenia? Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:788–796. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidecka S. Opioid mechanisms of some behavioral effects of ketamine. Pol J Pharmacol Pharm. 1987;39:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G, Alquicer G, Silva-Gomez AB, Zaldivar G, Stewart J, Quirion R, Srivastava LK. Alterations in dendritic morphology of prefrontal cortical and nucleus accumbens neurons in post-pubertal rats after neonatal excitotoxic lesions of the ventral hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2005;133:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallyas F, Farkas O, Mazlo M. Traumatic compaction of the axonal cytoskeleton induces argyrophilia: histological and theoretical importance. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2002;103:36–42. doi: 10.1007/s004010100424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella D, Hatton WJ, Rind HB, Rosen GD, von Bartheld CS. Differential tissue shrinkage and compression in the z-axis: implications for optical disector counting in vibratome-, plastic- and cryosections. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;124:45–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser JR, Glaser EM. Stereology, morphometry, and mapping: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;20:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Bagger P, Bendtsen TF, Evans SM, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Moller A, Nielsen K, Nyengaard JR, Pakkenberg B, et al. The new stereological tools: disector, fractionator, nucleator and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. Apmis. 1988;96:857–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Osterby R. Optimizing sampling efficiency of stereological studies in biology: or ‘do more less well!’. J Microsc. 1981;121:65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1981.tb01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HH, Briem T, Dzietko M, Sifringer M, Voss A, Rzeski W, Zdzisinska B, Thor F, Heumann R, Stepulak A, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Mechanisms leading to disseminated apoptosis following NMDA receptor blockade in the developing rat brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Arai N, Satoh J, Suzuki H, Katayama K, Tamagawa K, Morimatsu Y. Neurodegenerative mechanisms in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Child Neurol. 2002;17:725–730. doi: 10.1177/08830738020170101101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb HH, Lahti AC, Medoff DR, Cullen T, Tamminga CA. Effects of noncompetitive NMDA receptor blockade on anterior cingulate cerebral blood flow in volunteers with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2275–2282. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey GD, Honey RA, O’Loughlin C, Sharar SR, Kumaran D, Suckling J, Menon DK, Sleator C, Bullmore ET, Fletcher PC. Ketamine disrupts frontal and hippocampal contribution to encoding and retrieval of episodic memory: an fMRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:749–759. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vockler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova TI, Stefovska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999;283:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida K, Shimizu H, Hida H, Urakawa S, Ida K, Nishino H. Argyrophilic dark neurons represent various states of neuronal damage in brain insults: some come to die and others survive. Neuroscience. 2004;125:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru MJ, Ikonomidou C, Tenkova TI, Der TC, Dikranian K, Sesma MA, Olney JW. Distinguishing excitotoxic from apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:461–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen KL. Ketamine--can chronic use impair memory? Int J Addict. 1990;25:133–139. doi: 10.3109/10826089009056204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrard LE. On the role of the hippocampus in learning and memory in the rat. Behav Neural Biol. 1993;60:9–26. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the phencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–1308. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Carter LB. The anesthetics nitrous oxide and ketamine are more neurotoxic to old than to young rat brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Benshoff ND, Dikranian K, Zorumski CF, Olney JW, Wozniak DF. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Wozniak DF, Benshoff ND, Olney JW. A comparative evaluation of the neurotoxic properties of ketamine and nitrous oxide. Brain Res. 2001;895:264–267. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliatsos VE, Dawson TM, Kecojevic A, Zhou Y, Wang YF, Huang KX. Cortical interneurons become activated by deafferentation and instruct the apoptosis of pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14264–14269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404364101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudoh A, Takahira Y, Katagai H, Takazawa T. Small-dose ketamine improves the postoperative state of depressed patients. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:114–118. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00020. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Koffel B, LaPorte D, Tamminga CA. Subanesthetic doses of ketamine stimulate psychosis in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00131-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:455–467. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JO, Gundersen HJ, Nielsen J. Global spatial sampling with isotropic virtual planes: estimators of length density and total length in thick, arbitrarily orientated sections. J Microsc. 1998;191:238–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1998.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Pinals DA, Adler CM, Elman I, Clifton A, Pickar D, Breier A. Ketamine-induced exacerbation of psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairment in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:141–150. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell CR, Ehrlichman RS, Liang Y, Trief D, Kanes SJ, Karp J, Siegel SJ. Ketamine produces lasting disruptions in encoding of sensory stimuli. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:315–324. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh TJ, Jones MW, Quinn JJ, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB, Fanselow MS, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. Dentate gyrus NMDA receptors mediate rapid pattern separation in the hippocampal network. Science. 2007;317:94–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1140263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean RF, Baker AJ, Walker SE, Mazer CD, Wong BI, Harrington EM. Ketamine concentrations during cardiopulmonary bypass. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43:580–584. doi: 10.1007/BF03011770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Mitchell JB, Aitken DH, Bhatnagar S, Bodnoff SR, Iny LJ, Sarrieau A. The effects of neonatal handling on the development of the adrenocortical response to stress: implications for neuropathology and cognitive deficits in later life. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1991;16:85–103. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(91)90072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Mofeez A, Brandner B, Bromley L, Curran HV. Acute effects of ketamine on memory systems and psychotic symptoms in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:208–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJA, Rossellc Susan L, Peppera Fiona, Smartb James, Blackburnb James, Brandnerb Brigitta, Currana H Valerie. Semantic Priming after Ketamine Acutely in Healthy Volunteers and Following Chronic Self-Administration in Substance Users. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;59:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton PR, Gokhale AM, Ward NL, West MJ. Stereological length estimation using spherical probes. J Microsc. 2002;206:54–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima W, Ishida A, Lange MS, Gabrielson KL, Wilson MA, Martin LJ, Blue ME, Johnston MV. Apoptosis has a prolonged role in the neurodegeneration after hypoxic ischemia in the newborn rat. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7994–8004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07994.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, McHugh TJ, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. NMDA receptors, place cells and hippocampal spatial memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:361–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Sun LD, Quirk MC, Rondi-Reig L, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. Hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors are crucial for memory acquisition of one-time experience. Neuron. 2003;38:305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Farber NB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Selke G, Melson AK, Hershey T, Craft S, Olney JW. Ketamine-induced NMDA receptor hypofunction as a model of memory impairment and psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:106–118. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi KK, Nemmers B, Farber NB. Age has a similar influence on the susceptibility to NMDA antagonist-induced neurodegeneration in most brain regions. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;158:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW. New insights and new issues in developmental neurotoxicology. Neurotoxicology. 2002;23:659–668. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(01)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Muglia LJ, Jermakowicz WJ, D’Sa C, Roth KA. Ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation in the in vivo developing mouse brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2002a;9:205–219. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Qin YQ, Labruyere J, Ikonomidou C. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing C57BL/6 mouse brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002b;133:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Wozniak DF, Farber NB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. The enigma of fetal alcohol neurotoxicity. Ann Med. 2002c;34:109–119. doi: 10.1080/07853890252953509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Wozniak DF, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Farber NB, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Drug-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Brain Pathol. 2002d;12:488–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, Wozniak DF, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Farber NB, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Glutamate and GABA receptor dysfunction in the fetal alcohol syndrome. Neurotox Res. 2002e;4:315–325. doi: 10.1080/1029842021000010875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff R, Gonzales M, Sanacora G. Antidepressant effect of ketamine during ECT. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1385–1386. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin K. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rajgopal Y, Vemuri MC. Calpain activation and alpha-spectrin cleavage in rat brain by ethanol. Neurosci Lett. 2002;321:187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajji T, Chapman D, Eichenbaum H, Greene R. The role of CA3 hippocampal NMDA receptors in paired associate learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:908–915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4194-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richebe P, Rivat C, Laulin JP, Maurette P, Simonnet G. Ketamine improves the management of exaggerated postoperative pain observed in perioperative fentanyl-treated rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:421–428. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200502000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein RP, Levison SW. Gray matter oligodendrocyte progenitors and neurons die caspase-3 mediated deaths subsequent to mild perinatal hypoxic/ischemic insults. Dev Neurosci. 2005;27:149–159. doi: 10.1159/000085987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LM, Astur RS, Jung RE, Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Yeo RA. Selective cognitive impairments associated with NMDA receptor blockade in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:633–639. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin M, Ben-Abraham R, Gazit V, Tendler Y, Tashlykov V, Katz Y. Single-dose ketamine administration induces apoptosis in neonatal mouse brain. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;16:231–243. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.2005.16.4.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Uno H, Rebert CS, Finch CE. Hippocampal damage associated with prolonged glucocorticoid exposure in primates. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2897–2902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-09-02897.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel SJ, Brose N, Janssen WG, Gasic GP, Jahn R, Heinemann SF, Morrison JH. Regional, cellular, and ultrastructural distribution of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit 1 in monkey hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:564–568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel SJ, Ginsberg SD, Hof PR, Foote SL, Young WG, Kraemer GW, McKinney WT, Morrison JH. Effects of social deprivation in prepubescent rhesus monkeys: immunohistochemical analysis of the neurofilament protein triplet in the hippocampal formation. Brain Res. 1993;619:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonati A, Filosto M, Savio C, Tomelleri G, Tonin P, Dalla Bernardina B, Rizzuto N. Features of cell death in brain and liver, the target tissues of progressive neuronal degeneration of childhood with liver disease (Alpers-Huttenlocher disease) Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2003;106:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0698-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slikker W, Xu Z, Wang C. Application of a systems biology approach to developmental neurotoxicology. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;19:305–319. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein-Behrens B, Mattson MP, Chang I, Yeh M, Sapolsky R. Stress exacerbates neuron loss and cytoskeletal pathology in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5373–5380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05373.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiedl O, Birkenfeld K, Palve M, Spiess J. Impairment of conditioned contextual fear of C57BL/6J mice by intracerebral injections of the NMDA receptor antagonist APV. Behav Brain Res. 2000;116:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana R, Babu PP. Ethanol-induced alteration in N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2A C-terminus and protein kinase C activity in rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 2003;349:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashlykov V, Katz Y, Gazit V, Zohar O, Schreiber S, Pick CG. Apoptotic changes in the cortex and hippocampus following minimal brain trauma in mice. Brain Res. 2007;1130:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht D, Schmid L, Koller R, Vollenweider F, Hell D, Javitt D. Ketamine-induced deficits in auditory and visual context-dependent processing in healthy volunteers: implications for models of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000:57. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider FX, Leenders KL, Scharfetter C, Antonini A, Maguire P, Missimer J, Angst J. Metabolic hyperfrontality and psychopathology in the ketamine model of psychosis using positron emission tomography (PET) and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997;7:9–24. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(96)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CZ, Johnson KM. The Role of caspase-3 activation in phencyclidine induced neuronal death in postnatal rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1178–1194. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ. New stereological methods for counting neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 1993;14:275–285. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90112-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ. Stereological methods for estimating the total number of neurons and synapses: issues of precision and bias. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak DF, Brosnan-Watters G, Nardi A, McEwen M, Corso TD, Olney JW, Fix AS. MK-801 neurotoxicity in male mice: histologic effects and chronic impairment in spatial learning. Brain Res. 1996;707:165–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak DF, Dikranian K, Ishimaru MJ, Nardi A, Corso TD, Tenkova T, Olney JW, Fix AS. Disseminated corticolimbic neuronal degeneration induced in rat brain by MK-801: potential relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:305–322. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Schlenger W, Galvin D. Concurrent Use of Methamphetamine, MDMA, LSD, Ketamine, GHB, and flunitrazepam among American Youths. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young C, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Qin YQ, Tenkova T, Wang H, Labruyere J, Olney JW. Potential of ketamine and midazolam, individually or in combination, to induce apoptotic neurodegeneration in the infant mouse brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:189–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SL, Bohenek DL, Fanselow MS. NMDA processes mediate anterograde amnesia of contextual fear conditioning induced by hippocampal damage: immunization against amnesia by context preexposure. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:19–29. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsombok A, Toth Z, Gallyas F. Basophilia, acidophilia and argyrophilia of “dark” (compacted) neurons during their formation, recovery or death in an otherwise undamaged environment. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;142:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]