Abstract

By proposing TSH as a key negative regulator of bone turnover, recent studies in TSH receptor (TSHR) null mice challenged the established view that skeletal responses to disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis result from altered thyroid hormone (T3) action in bone. Importantly, this hypothesis does not explain the increased risk of osteoporosis in Graves’ disease patients, in which circulating TSHR-stimulating antibodies are pathognomonic. To determine the relative importance of T3 and TSH in bone, we compared the skeletal phenotypes of two mouse models of congenital hypothyroidism in which the normal reciprocal relationship between thyroid hormones and TSH was intact or disrupted. Pax8 null (Pax8−/−) mice have a 1900-fold increase in TSH and a normal TSHR, whereas hyt/hyt mice have a 2300-fold elevation of TSH but a nonfunctional TSHR. We reasoned these mice must display opposing skeletal phenotypes if TSH has a major role in bone, whereas they would be similar if thyroid hormone actions predominate. Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice both displayed delayed ossification, reduced cortical bone, a trabecular bone remodeling defect, and reduced bone mineralization, thus indicating that the skeletal abnormalities of congenital hypothyroidism are independent of TSH. Treatment of primary osteoblasts and osteoclasts with TSH or a TSHR-stimulating antibody failed to induce a cAMP response. Furthermore, TSH did not affect the differentiation or function of osteoblasts or osteoclasts in vitro. These data indicate the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis regulates skeletal development via the actions of T3.

OSTEOPOROSIS IS A major health care priority affecting 50% of women and 20% of men over 50, and costing €31 billion in Europe and $14 billion in the United States each year (1,2). Thyrotoxicosis is an important cause of secondary osteoporosis; uncontrolled hyperthyroidism accelerates skeletal remodeling and increases bone loss due to uncoupling of bone resorption and formation (3). Moreover, a history of thyrotoxicosis is associated with an increased fracture risk in later life (4). Although early recognition and treatment of thyrotoxicosis means that overt bone disease is now uncommon, prospective studies have shown a 4-fold increased fracture risk in postmenopausal women with low TSH levels (5).

The detrimental effects of thyrotoxicosis have long been attributed to actions of excess T3 on skeletal T3 receptors (TRs) (6). However, recent studies have challenged this interpretation (7). Osteoblasts and osteoclasts were found to express the TSH receptor (TSHR) and respond to TSH in vitro, whereas juvenile TSHR null (TSHR−/−) mice with congenital hypothyroidism and treated with thyroid extract displayed high bone turnover osteoporosis (7). These findings were interpreted to indicate that TSH is a major and direct inhibitor of bone turnover. Importantly, this model is inconsistent with the increased risk of osteoporotic fracture in Graves’ disease patients, in whom TSHR-stimulating antibodies are pathognomonic (4).

The TSHR acts principally via adenylate cyclase to regulate thyroid follicular cell proliferation and thyroid hormone synthesis and release (8). Deletion of the Tshr gene leads to congenital hypothyroidism with undetectable thyroid hormone levels due to thyroid follicular hypoplasia. The lack of negative feedback on pituitary thyrotrophs results in grossly elevated TSH. TSHR−/− mice display developmental delay and growth retardation and survive beyond 4 wk only if supplemented with thyroid extract (9). In man, congenital and juvenile hypothyroidism also causes growth arrest and delayed bone maturation, whereas thyroid hormone replacement results in rapid catch-up growth and failure to obtain full predicted height (10,11). Thus, high bone turnover reported in TSHR−/− mice treated with thyroid extract (7) may represent catch-up growth after treatment of juvenile hypothyroidism.

To determine the relative importance of T3 and TSH in bone, it is necessary to dissociate their inverse relationship that results from negative feedback regulation of TSH by thyroid hormones. We compared the skeletal phenotypes of two mouse models of congenital hypothyroidism in which this relationship was intact or disrupted. Pax8 null (Pax8−/−) mice lack a transcription factor essential for thyroid development and display severe hypothyroidism with grossly elevated TSH (12,13). Hyt/hyt mice, harbor a TSHR loss-of-function mutation also resulting in thyroid hypoplasia, severe hypothyroidism, and grossly elevated TSH (14). Thus, Pax8−/− mice represent a model of high TSH with a normal TSHR, whereas hyt/hyt mice have high TSH but a nonfunctional TSHR. If TSH has a physiologically important role in bone, we reasoned these mice must display opposing skeletal phenotypes. We also investigated TSH actions in primary osteoblasts and osteoclasts by determining TSHR expression, its effects on cell differentiation and function, and the cellular cAMP response to TSH and TSHR-stimulating antibodies.

RESULTS

Thyroid Status in Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice

Pax8−/− mice have undetectable T4 and T3 and 1900-fold elevated levels of TSH (12,13). Hyt/hyt mice are also grossly hypothyroid, but their TSH levels have not been reported. When measured in the present study, T4 was reduced by 95% and TSH elevated 2300-fold in hyt/hyt mice, whereas levels were similar in wild-type (WT) mice and heterozygote hyt/+ (HET) mice [total T4 (mg/dl): WT 5.66 ± 0.80, HET 4.90 ± 0.68, Hyt/Hyt 0.33 ± 0.05; TSH (mU/liter): WT 23.0 ± 7.6, HET 36.0 ± 8.7, Hyt/Hyt 52,856 ± 5515; (n =3–6)].

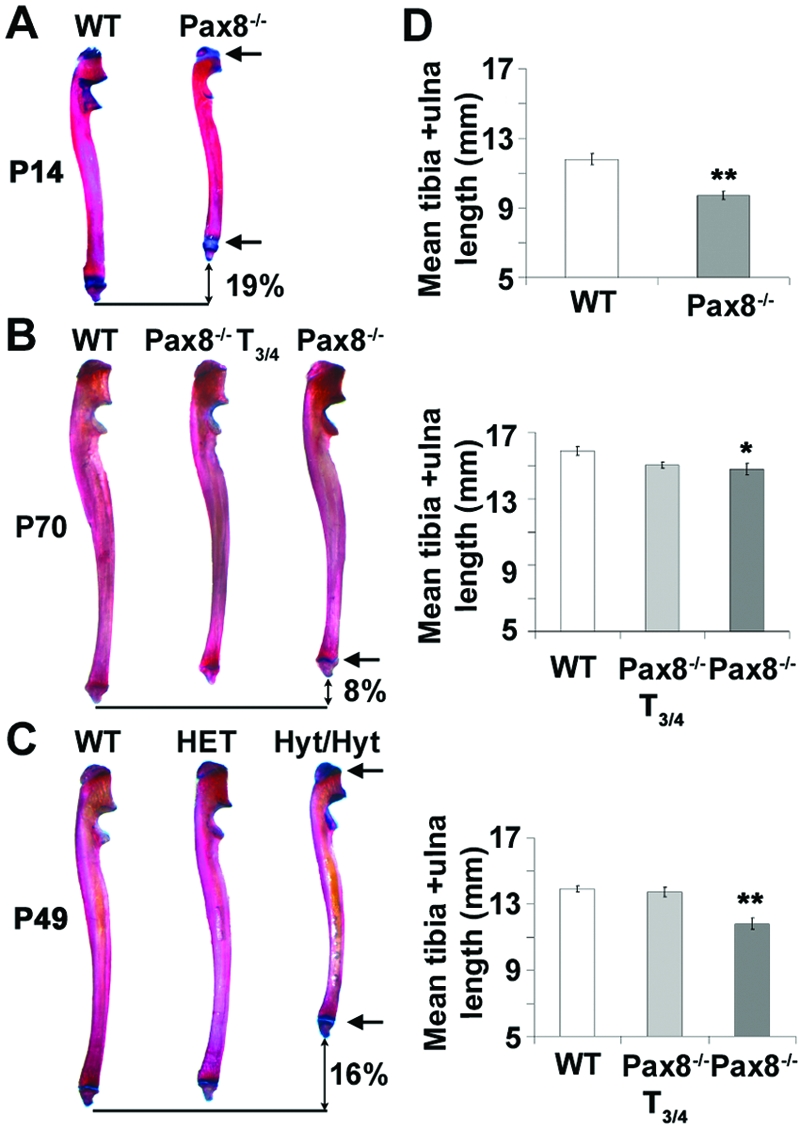

Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice Both Have Severe Growth Delay and Delayed Ossification

Pax8−/− limbs were 19% shorter than WT littermates at postnatal d 14 (P14) (P < 0.01; n =3–5) and 8% shorter at P70 (P < 0.05; n =3–5) and exhibited delayed formation of secondary ossification centers (Fig. 1). Transient treatment with T3 and T4 (T3/4) before weaning between P8 and P13 ameliorated this phenotype. Hyt/hyt limbs were 16% shorter than HET and WT littermates at P49 (P < 0.01; n =3–6) and displayed delayed formation of secondary ossification centers. Thus, growth impairment in both Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice results from delayed endochondral ossification.

Figure 1.

Growth and Skeletal Development of Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice

A–C, Ulnas from P14 Pax8−/− (A), P70 Pax8−/− and T3/4-treated (between P8 and P13) Pax8−/− (B), and P49 hyt/hyt, HET, and WT littermates (C) stained with alcian blue and alizarin red. Arrows indicate delayed formation of secondary epiphyses and wider growth plates in Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice. D, Mean lengths of tibia and ulna. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 mutant vs. WT; n =3–6, 2-tailed Student’s t test or ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

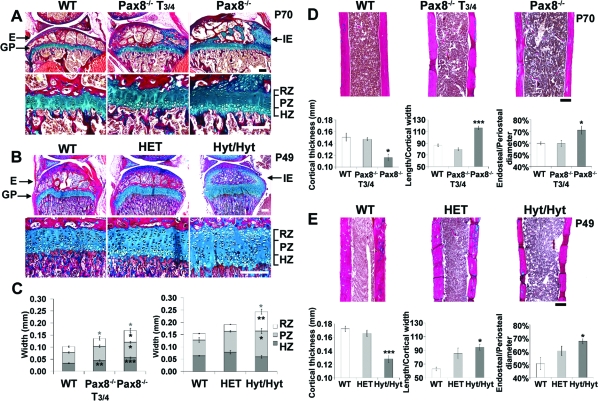

Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice Both Have Impaired Chondrocyte Differentiation, Reduced Cortical Bone, and Impaired T3 Target Gene Expression in Osteoblasts

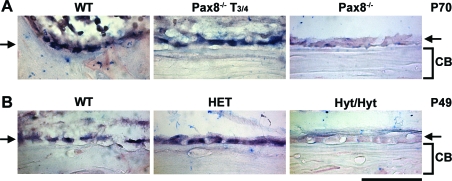

Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice had wider growth plates and immature secondary ossification centers (Fig. 2, A and B). The extent of the reserve zone (RZ), proliferative zone (PZ), and hypertrophic zone (HZ) in the growth plate was determined by collagen II and X in situ hybridization as described (15). The increased growth plate width resulted from widening of all zones in Pax8−/− mice but only of the RZ and PZ in hyt/hyt mice. Strikingly, the proximal tibia epiphysis exhibited delayed and incomplete ossification in Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice and was accompanied by disrupted growth plate architecture in both mutant strains. Treatment of Pax8−/− mice with T3/4 between P8 and P13 ameliorated these abnormalities (Fig. 2A). Growth plate measurements in HET mice were similar to WT. Mid-diaphysis cortical bone thickness was determined in midline sagittal sections (Fig. 2, D and E) and was reduced by 23% in Pax8−/− (P < 0.05; n = 3) and 26% in hyt/hyt (P < 0.001; n = 3) mice. These reductions did not merely reflect the proportional change associated with decreased bone length because the ratio of femur length to cortical bone width was increased by 35% in Pax8−/− (P < 0.001) and 50% in hyt/hyt (P < 0.05) mice. Furthermore, the ratio of the diameter between endosteal cortical bone surfaces to the diameter between periosteal surfaces was increased in both strains. Together with these observations, expression of the T3 target gene Fgfr1 (16,17) was markedly reduced in osteoblasts in both Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice compared with WT, T3/4-treated Pax8−/− mice, and HET littermates (Fig. 3). Furthermore, T3/4 treatment of Pax8−/− mice between P8 and P13 normalized the skeletal phenotype, whereas cortical bone measurements also did not differ between HET and WT mice. Thus, Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice both have similar defects of endochondral ossification and cortical bone deposition together with a similar impairment of T3 target gene expression in osteoblasts.

Figure 2.

Histological Analysis of Ossification in Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice

A and B, Proximal tibia sections stained with alcian blue/van Gieson from P70 Pax8−/− and T3/4-treated (between P8 and P13) Pax8−/− mice (A) and P49 hyt/hyt, HET, and WT littermates (B). C, Widths of growth plate zones (RZ, PZ, and HZ) and total growth plate (RZ+PZ+HZ) from P70 WT, T3/4-treated Pax8−/−, and Pax8−/− or P49 WT, HET, and hyt/hyt mice. D and E, Mid-diaphysis femurs are shown in P70 WT, T3/4-treated Pax8−/− and Pax8−/− mice (D) or P49 WT, HET, and hyt/hyt mice (E). Graphs show cortical thickness, length/cortical thickness, and endosteal/periosteal diameter ratios in P70 WT, T3/4-treated Pax8−/−, and Pax8−/− (D) and P49 WT, HET, and hyt/hyt mice (E). E, Epiphysis; GP, growth plate; IE, immature epiphysis. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 mutant vs. WT; n =3–7; ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Figure 3.

Expression of Fgfr1 in Osteoblasts in Pax8−/−, T3/4-Treated Pax8−/−, and Hyt/Hyt Mice

In situ hybridization of Fgfr1 expression in osteoblasts from P70 Pax8−/− and T3/4-treated Pax8−/− mice (A) and P49 hyt/hyt, HET, and WT littermates (B). Arrows indicate layer of cortical bone lining osteoblasts. CB, Cortical bone. Scale bar, 50 μm.

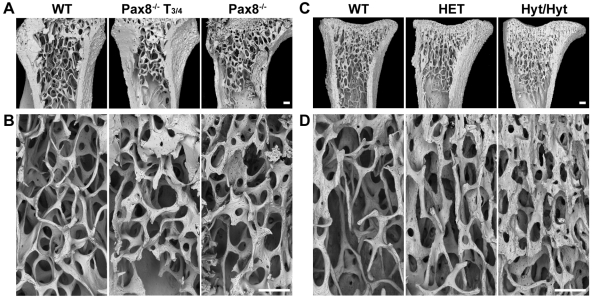

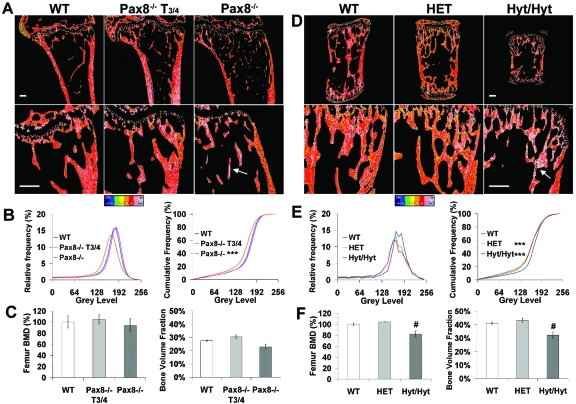

Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice Both Have Impaired Trabecular Remodeling and Reduced Bone Mineralization

Bone microarchitecture was characterized by topographical backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM). Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt long bones had reduced cortical thickness and abnormal trabecular architecture (Fig. 4). In Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice, trabeculae were coarser, more plate-like, and of increased connectivity. Even transient thyroid hormone treatment of Pax8−/− mice improved the trabecular abnormalities (Fig. 4, A and B), and HET mice displayed a similar phenotype to WT (Fig. 4, C and D). Bone mineralization was determined in Pax8−/− proximal humerus and hyt/hyt caudal vertebrae by quantitative compositional BSE-SEM (qBSE-SEM) (Fig. 5, A and D). The relative and cumulative frequencies of micromineralization densities were markedly reduced in both Pax8−/− (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; D statistic 17.2; P < 0.001) and hyt/hyt (D statistic 16.2; P < 0.001) mice (Fig. 5, B and E). Mineralization in HET mice was similar to hyt/hyt, which reflects the additional presence of abnormally retained and highly mineralized calcified cartilage in hyt/hyt trabeculae. Similarly, Pax8−/− bone retained calcified cartilage, consistent with a trabecular bone remodeling defect in both strains. T3/4 treatment of Pax8−/− mice between P8 and P13 normalized bone mineralization density and corrected the remodeling defect. Bone volume fraction (BVF) was reduced by 22% in hyt/hyt mice (P < 0.05) but was indistinguishable between HET and WT. A similar trend was present in Pax8−/− mice in which a 17% reduction was observed (Fig. 5, C and F), and this was normalized by T3/4 between P8 and P13. Femoral bone mineral density (BMD) was also reduced by 18% in hyt/hyt mice (P < 0.05), and a similar trend was evident in Pax8−/− mice in which a 6% reduction was seen (Fig. 5, C and F). Thus, Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice both have impaired trabecular bone remodeling and decreased bone mineralization.

Figure 4.

Topographic Three-Dimensional BSE-SEM Analysis of Bone Structure in Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice

BSE-SEM views of proximal humerus (A and B) from P70 WT, T3/4-treated (between P8 and P13) Pax8−/−, and Pax8−/− mice and proximal tibia (C and D) from P49 WT, HET, and hyt/hyt mice. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Figure 5.

qBSE-SEM Compositional Analysis of Mineralization Densities and BVF in Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice

Mineralization densities in proximal humerus (A) from P70 WT, T3/4-treated (between P8 and P13) Pax8−/−, and Pax8−/− mice and caudal vertebrae (D) from P49 WT, HET, and hyt/hyt mice. Gray-scale images were pseudocolored with low mineralization density in blue and high density in gray. Arrows indicate highly mineralized calcified cartilage. Scale bars, 200 μm. B and E, Relative and cumulative frequencies of mineralization densities. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 mutant vs. WT; n = 2–4; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. C and F, BMD, determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, and BVF, determined by BSE-SEM, in P70 WT, T3/4-treated Pax8−/−, and Pax8−/− mice (C) and P49 WT, HET, and hyt/hyt mice (F). #, P < 0.05 for BMD or BVF in mutant vs. WT; n = 2–5 per group; ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

Osteoblasts Express TSHR, but TSH Fails to Induce cAMP or Alter Differentiation and Function

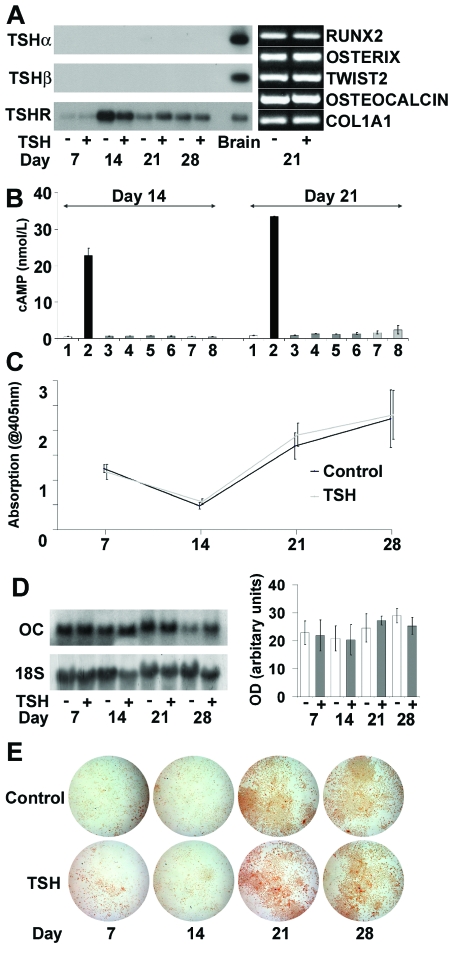

Primary osteoblasts cultured for 28 d expressed Runx2 (runt-related transcription factor 2), Twist2 (second homolog of Drosophila twist), SP7 (osterix), Bglap2 (osteocalcin), and ColIa1 (collagen type I α1 subunit) mRNAs, confirming their mature osteoblast phenotype. Expression of these osteoblast markers on d 21 of culture was evident in cells cultured in the absence and presence of bovine TSH (bTSH) (Fig. 6A). Differentiating osteoblasts expressed TSHR mRNA but did not express TSHα or -β mRNAs (Fig. 6A). Intracellular cAMP levels were determined on d 14 and 21. Forskolin induced a strong cAMP response in osteoblasts but no response was elicited by bTSH, human TSH (hTSH), a TSHR-stimulating antibody (M22), or a nonstimulating TSHR antibody (3G4) (18,19,20) (Fig. 6B). By contrast, the stimulating ligands each increased cAMP in FRTL-5 thyroid follicular cells (bTSH, P < 0.01; hTSH P < 0.05; M22 P < 0.05; n =2 experiments performed in duplicate), whereas the nonstimulating 3G4 antibody failed to elicit a response (Fig. 7B). Consistent with these findings, alkaline phosphatase activity and osteocalcin mRNA expression were unaffected by treatment with TSH throughout the 28-d period of osteoblast culture (Fig. 6, C and D). Furthermore, osteoblast function, as determined by alizarin red staining of mineralized nodules, was unaffected by TSH (Fig. 6E). Thus, osteoblasts express TSHR mRNA, but their differentiation and function are not affected by TSH.

Figure 6.

Primary Calvarial Osteoblast Cultures

A, Southern blot RT-PCR of TSHα, TSHβ, and TSHR mRNAs on d 7, 14, 21, and 28 of culture with or without bTSH (10 U/liter) and expression of Runx2, Osterix, Twist2, Osteocalcin, and ColIa1 mRNAs on d 21. B, cAMP response (±sem) to 1) medium alone, 2) forskolin (10 μmol), 3) bTSH (10 U/liter), 4) bTSH (100 U/liter), 5) hTSH (10 U/liter), 6) hTSH (100 U/liter), 7) 3G4 nonstimulating TSHR antibody, and 8) M22 TSHR-stimulating antibody. C, Alkaline phosphatase activity (±sem). D, Representative Northern blot analysis of osteocalcin (OC) mRNA expression on d 7, 14, 21, and 28 of culture with or without bTSH (10 U/liter) and graph showing mean osteocalcin mRNA levels from three independent experiments normalized to expression of 18S rRNA. E, Alizarin red staining.

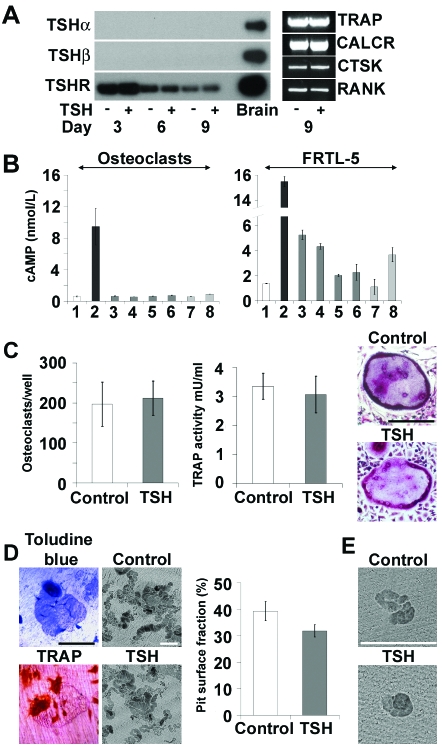

Figure 7.

Osteoclast Cultures

A, Southern blot RT-PCR of TSHα, TSHβ, and TSHR mRNAs on d 6, 9, and 12 of culture with or without bTSH (10 U/liter) and expression of Trap, Calcr, Ctsk, and Rank mRNAs on d 9. B, cAMP response (±sem) to 1) medium alone, 2) forskolin (10 μmol), 3) bTSH (10 U/liter), 4) bTSH (100 U/liter), 5) hTSH (10 U/liter), 6) hTSH (100 U/liter), 7) 3G4 nonstimulating TSHR antibody, and 8) M22 TSHR-stimulating antibody in osteoclasts and thyroid follicular FRTL-5 cells. C, Cell number (±sem), morphology, and TRAP activity (±sem) on d 9. D, Toluidine blue- and TRAP-stained osteoclasts cultured on dentine slices for 9 d. Graph shows the fraction of resorbed surface (±sem) determined by BSE-SEM. E, Resorption pits formed by bone marrow osteoclasts cultured for 12 h. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Osteoclasts Express TSHR, but TSH Fails to Induce cAMP or Alter Differentiation and Function

Osteoclasts differentiated for 9 d with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) with or without bTSH expressed Acp5 [tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)], Calcr (calcitonin receptor), Ctsk (cathepsin K), and Tnfrsf11a (receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB) mRNAs, confirming their osteoclast phenotype (Fig. 7A). Differentiating osteoclasts expressed TSHR mRNA but did not express TSHα or -β mRNAs (Fig. 7A). Intracellular cAMP levels were determined on d 9 (Fig. 7B). Forskolin induced a strong cAMP response but, as in osteoblasts, no response was elicited after treatment with bTSH, hTSH, or the M22 TSHR-stimulating antibody. Osteoclast numbers, morphology, and TRAP activity, a marker of osteoclast differentiation, did not differ in the absence or presence of TSH (Fig. 7C). Osteoclasts were also differentiated on dentine slices over a 9-d period, after which the area of resorbed dentine surface was determined by topographical BSE-SEM. The total osteoclast pit resorption surface area was unaffected by TSH (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, the size and number of resorption pits formed over a 12-h period by osteoclasts extracted directly from bone and not exposed to M-CSF and RANKL was not affected by TSH (Fig. 7E). Thus, osteoclasts express TSHR mRNA, but their differentiation and activity are not affected by TSH.

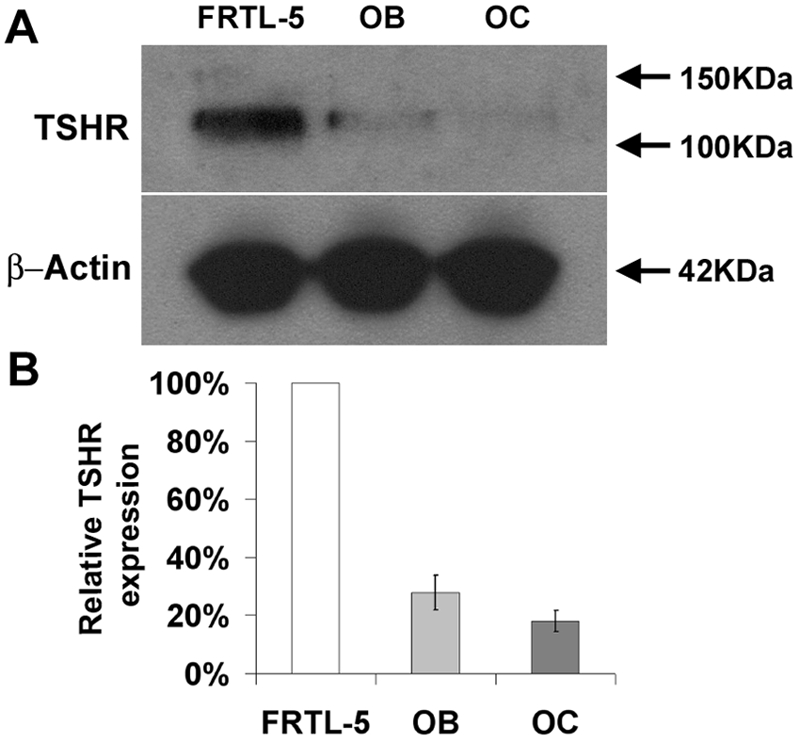

TSHR Protein Is Expressed at Low Levels in Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts

RT-PCR studies demonstrated TSHR mRNA expression in osteoblasts and osteoclasts, but treatment with TSH or a TSHR-stimulating antibody elicited no cAMP response. Thus, we investigated TSHR protein expression in Western blots by an optimized enhanced chemiluminescence method. TSHR protein was expressed at the limit of detection in both osteoblasts and osteoclasts, whereas TSHR protein was readily observed in FRTL-5 thyroid follicular cells (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

TSHR Protein Expression

Western blot of TSHR expression in lysates from thyroid follicular FRTL-5 cells and primary osteoblasts (OB) and osteoclasts (OC).

DISCUSSION

These studies compared two divergent models of congenital hypothyroidism in which grossly elevated levels of TSH occurred in the presence of either a normal (Pax8−/−) or a nonfunctional (hyt/hyt) TSHR. We reasoned these mice must display opposing skeletal phenotypes if TSH has a major role in bone, whereas they would be similar if thyroid hormone actions predominate. The power of this approach lies with the simple hypothesis and the extremes of the two mouse models. We used state-of-the-art structural analysis of skeletal phenotype and quantitation of bone mineralization to provide an unequivocal answer. Thus, the finding that Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice both have delayed ossification, reduced cortical bone deposition, impaired osteoblast T3 target gene expression, a trabecular bone remodeling defect, and reduced mineralization rather than opposing skeletal phenotypes demonstrates that the skeletal abnormalities of congenital hypothyroidism must be independent of systemic TSH concentrations. This conclusion is supported by the observation that TSH did not influence primary osteoblast or osteoclast differentiation and functional activity in vitro.

Skeletal Responses to Hypothyroidism Are Independent of Systemic TSH

Because TSH action is maximal in Pax8−/− mice (grossly elevated TSH and a functional TSHR) but absent in hyt/hyt mice (grossly elevated TSH but a nonfunctional TSHR), the similarity of their phenotypes reflects the detrimental skeletal effects of severe thyroid hormone deficiency, as reflected by reduced osteoblast Fgfr1 expression in both Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice, rather than any effect of TSH in bone. Thus, the skeletal abnormalities in both Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice, which have thyroid gland agenesis and hypoplasia, respectively, are characteristic of juvenile hypothyroidism in humans and rodents (10,11,15,21) and reflect the well-described impairment of chondrocyte, osteoblast, and osteoclast functions that result from a lack of thyroid hormones (22,23,24,25,26,27,28). This interpretation is supported further by previous data in TRα0/0 mice, which lack all TRα isoforms, and TRα1PV/+ mice, which harbor a severe dominant-negative mutation in TRα1. Both strains are euthyroid with normal TSH levels but display delayed endochondral ossification and reduced bone mineralization due to impaired T3 action in bone (15,21). Thus, the skeletal phenotype of congenital hypothyroidism is independent of systemic TSH.

Rapid Catch-Up Growth after Thyroid Hormone Treatment

Juvenile hypothyroidism is an important cause of growth delay in children. Thyroid hormone replacement results in a rapid increase in growth velocity that often persists until cessation of growth at puberty (10). Furthermore, the deficit in predicted final height correlates with the severity and duration of hypothyroidism (10,11).

The proposed key role for TSH in bone, which resulted from studies of TSHR−/− mice (7), conflicts with the current observations in Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice. Importantly, TSHR−/− mice have congenital hypothyroidism (9) but received thyroid extract only from weaning at 3 wk of age (7). Critically, however, normal growth velocity in mice is maximal before this time point when T4 and T3 levels rise rapidly to reach their physiological peak at 2 wk of age (12,15). Thus, the TSHR−/− mice were grossly hypothyroid during this critical stage of thyroid hormone-dependent skeletal development, and their reported phenotype may reflect the skeletal manifestations of catch-up growth and accelerated bone development in response to delayed thyroid hormone replacement.

To investigate the sensitivity of the developing skeleton to thyroid hormones before weaning, Pax8−/− mice were treated with T3/4 between P8 and P13. Amelioration of the phenotype by T3/4 treatment demonstrates the critical nature of this period for skeletal development and its dependence on thyroid hormones. Importantly, T3/4 treatment increased cortical thickness (Fig. 2D) and mineralization of long bones (Fig. 5B) compared with untreated Pax8−/− mice. This period of T3/4 treatment can be expected to transiently lower TSH levels. Even so, the observed increase in cortical thickness and bone mineralization in response to T3/4 treatment is again inconsistent with the proposal of Abe et al. (7), which predicts that a fall in TSH should result in a further reduction in bone mineralization. Thus, T3/4 treatment of Pax8−/− mice strengthens the conclusion that the skeletal effects of congenital hypothyroidism result from a lack of thyroid hormones and are independent of circulating TSH.

Osteoblast and Osteoclast Differentiation and Function Are Independent of TSH

Although the in vivo data demonstrate that the skeletal consequences of congenital hypothyroidism cannot be mediated by TSH, it was also necessary to investigate whether TSH could exert paracrine actions in skeletal cells. TSHα or -β mRNAs were not expressed in osteoblasts or osteoclasts at any stage of differentiation, indicating TSH does not have a paracrine role. Moreover, equivalent levels of alkaline phosphatase activity, osteocalcin expression, and mineral deposition observed in osteoblast cultures in the absence or presence of TSH indicates that TSH does not regulate osteoblast differentiation and function in vitro. Similarly, the presence of comparable cell numbers, TRAP activities, and dentine resorption in osteoclast cultures in the absence or presence of TSH indicates that TSH does not influence osteoclast differentiation and function in vitro. To exclude the possibility that high concentrations of M-CSF and RANKL masked an effect of TSH on osteoclast activity, we also examined the response of freshly isolated bone marrow osteoclasts to TSH in the absence of these differentiation factors in 12-h dentine resorption assays. TSH did not affect the size and number of resorption pits in these experiments. Thus, TSH does not influence the differentiation and function of osteoblasts or osteoclasts in vitro.

Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts Express TSHR but Do Not Signal via the Canonical cAMP Pathway

Osteoblasts and osteoclasts express low levels of TSHR protein, but no cAMP response to TSH or a TSHR-stimulating antibody was evident despite detectable basal levels of intracellular cAMP and a robust response to forskolin in both cell types. This paradox suggests that the very low levels of TSHR in skeletal cells elicit negligible cAMP responses or that the canonical cAMP pathway is not involved in TSH signaling in bone. Although cAMP is recognized as the major second messenger in thyroid follicular cells, alternative pathways have been implicated in both thyroid and extrathyroidal tissues (8,29,30). In thyroid follicular cells, the TSHR associates with various G proteins (31), and TSH activation of alternative pathways has been reported; these include phospholipase C (PLC)/protein kinase C (PKC) (8,32), Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT3) (33,34), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (35). It remains possible that these noncanonical pathways could mediate actions of TSH in skeletal cells. Nevertheless, the similarity of the phenotypes in Pax8−/− and hyt/hyt mice, and the lack a demonstrable effect of TSH in vitro, suggest that any actions of TSH in bone are likely to be minor in comparison with the effects of T3.

In summary, these studies demonstrate that the skeletal abnormalities of congenital hypothyroidism result from thyroid hormone deficiency and are independent of systemic TSH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pax8−/− and Hyt/Hyt Mice

Pax8−/− mice were housed in a certified animal facility according to procedures approved by l’Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon local animal care and use committee. Pax8−/− and WT littermates were derived from heterozygote crosses to overcome confounding influences of a maternal homozygote genotype and were analyzed at P14 and P70. Untreated Pax8−/− mice survived spontaneously (36), but to determine the effect of thyroid hormones before weaning, some Pax8−/− mice received a daily ip injection of T4 (10 μg) and T3 (1 μg) between P8 and P13. Hyt/hyt mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and hyt/hyt, HET, and WT littermates were derived from heterozygous crosses and analyzed at P49.

Biochemical Measurements

Total T4 was measured in P49 WT, hyt/+, and hyt/hyt littermate mice by coated-tube RIA adapted for mouse serum (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA), and TSH was determined by a sensitive, heterologous, disequilibrium, double-antibody precipitation RIA, as described (37,38).

Skeletal Preparations

Limbs from P14 and P70 Pax8−/− and P49 hyt/hyt mice and their littermates were stained with alizarin red and alcian blue (15,39). Skeletal preparations were photographed using a Leica MZ75 binocular microscope (Leica AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland), Leica DFC320 digital camera, Leica IM50 Digital Image Manager, and Leica Twain Module DFC320 image acquisition software. After linear calibration, tibia and ulna lengths were determined using ImageJ version 1.33u software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Histology

Limbs were fixed for 48 h in 10% neutral buffered formalin and decalcified in 10% formic acid and 10% neutral buffered formalin. P14 limbs were decalcified for 3 d, whereas P49 and P70 limbs were decalcified for 7 d. Decalcified bones were embedded in paraffin and 3-μm sections stained with van Gieson and alcian blue 8GX and photographed using a Leica DM LB2 microscope and DFC320 digital camera. The expression of collagen II and collagen X mRNA was analyzed in growth plate sections by in situ hybridization and used to identify proliferative and hypertrophic zones in growth plate sections as described (15,17,39,40). Mean values for widths of the RZ, PZ, HZ, and total growth plate were calculated from measurements taken at four positions across the proximal tibia using ImageJ. Mean cortical bone dimensions were calculated from measurements taken at 10 separate positions along the mid-diaphysis of long bones. In all cases, data from at least two different levels of sectioning were compared to ensure consistency of data.

In Situ Hybridization

Fgfr1 mRNA expression was analyzed by in situ hybridization as described (15,17,40,41). Studies were performed in duplicate on sections obtained from at least three mice per genotype and repeated three times. Experimental conditions were optimized separately for comparison of Pax8−/−, T3/4-treated Pax8−/−, and WT littermates and comparison of hyt/hyt, HET, and WT littermates.

BSE-SEM

Analysis of bone microarchitecture was determined by BSE-SEM. For topographical three-dimensional imaging, dissected bones were fixed in 70% ethanol and opened longitudinally by removing half the cortical bone and medullary trabecular elements with a fine tungsten carbide milling tool. Samples were cleaned of cell remnants by maceration with an alkaline bacterial pronase, washed, dried, and coated with carbon and imaged using backscattered electrons, generally at 30-kV beam potential.

The distribution of mineralization densities within calcified tissues was quantified by digital image analysis of compositional BSE images at the cubic micrometer volume resolution scale. Bones were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in polymethylmethacrylate. Block faces were cut through the specimens, which were then polished, coated with carbon, and analyzed using backscattered electrons in a Zeiss DSM962 digital scanning electron microscope, equipped with an annular solid-state BSE detector (KE Electronics, Toft, Cambridgeshire, UK), operated at 20 kV and 0.5 nA. The mineralization densities of the calcified tissues were determined by comparison with halogenated dimethacrylate standards, C22H25O10Br [mean BSE coefficient according to the procedure of Lloyd (42) = 0.1159] to C22H25O10I (mean BSE coefficient 0.1519). Increasing gradations of micromineralization density were represented in eight equal intervals by a pseudocolor scheme for presentation of digital images (43,44).

BMD was also determined using a PIXImus dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry mouse densitometer according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Faxitron, Wheeling, IL).

Cell Culture

Primary osteoblasts were prepared from P2 neonatal CD1 mice. Calvariae were washed in PBS containing penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (1.5 μg/ml) and diced. Bone fragments were digested twice with trypsin (0.5%) in EDTA-PBS for 10 min at 37 C and then five times in collagenase II (0.2%) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) for 30 min at 37 C. The final three digests were pooled and cells resuspended in α-MEM containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) and antibiotics. Cells were replated at a density of 5 × 103 cell/ml in medium containing ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml) and β-glycerophosphate (5 mm) with or without bTSH (10 U/liter). Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined on d 7, 14, 21, and 28 of culture. Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed in Triton X-100/PBS (0.1%). After addition of p-nitrophenylphosphate substrate (200μl) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), alkaline phosphatase activity was measured at 405 nm using Softmax Pro software in a Spectramax 340PC spectrophotometer. Mineralization was determined by alizarin red staining on d 7, 14, 21, and 28. Cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 70% ethanol, rehydrated, and stained for 5 min (45). Digital images were obtained using a Leica MZ75 microscope and DFC320 camera.

Osteoclast progenitors were prepared from P70 CD1 mice. Bone marrow was flushed from long bones and filtered through a 70-μm mesh (Becton Dickinson UK, Oxford, UK). Cells were resuspended in α-MEM containing HI-FBS (10%), antibiotics and M-CSF (25 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), plated at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml and cultured overnight. Nonadherent cells were removed and cultured at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml in the presence of M-CSF (25 ng/ml) and RANKL (10 ng/ml) (R&D Systems) with or without bTSH (10 U/liter). Osteoclast numbers were determined on d 9 of culture. Adherent cells were stained for TRAP expression using Sigma kit 386A according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Digital images were obtained using an Olympus CKX31 microscope and C3030 digital camera. Cell numbers were determined by two independent observers, and mature osteoclasts were defined as TRAP-positive cells, greater than 70 μm in size, and containing three or more nuclei (46). Osteoclast TRAP activity was also determined on d 9. Cells were washed in PBS and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS, and TRAP activity was determined using a Sigma CS0740 kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Dentine Resorption Assay

Nonadherent bone marrow cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml onto dentine slices (ImmunoDiagnostic Systems Ltd., Boldon, UK) and cultured in α-MEM containing HI-FBS (10%), antibiotics, M-CSF (25 ng/ml), and RANKL (10 ng/ml) with or without bTSH (10 U/liter). Osteoclasts were visualized on d 9 after staining with toluidine blue or TRAP (Sigma kit 386A). Dentine slices were sonicated, dried, carbon coated, and imaged by topographic BSE-SEM. The area of dentine surface resorbed was quantified using ImageJ. Direct dentine resorption assays were performed using fresh osteoclasts prepared from long bones of neonatal P3 CD1 mice (47). Bones were diced in α-MEM containing HI-FBS (10%), and a 60-μl cell suspension was seeded onto each dentine slice. After 1 h incubation, nonadherent cells were removed, and 1 ml α-MEM containing HI-FBS with or without bTSH (10 U/liter) was added. Cells were cultured for another 11 h at 37 C in 5% CO2.

RT-PCR Analysis

RNA was isolated from primary osteoblasts on d 7, 14, 21, and 28 and osteoclasts on d 3, 6, and 9. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (5 μg) using the Superscript II First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). cDNA (2 μl) was used for PCR amplification of osteoblast and osteoclast markers. Nucleotide positions of primers are given in the 5′–3′ direction: Tsha, forward (117–136) and reverse (557–576) (GenBank accession no. NM_009889); Tshb, forward (281–300) and reverse (500–519) (NM_009432); Tshr, forward (130–149) and reverse (400–418) (NM_011648); Runx2, forward (670–690) and reverse (1031–1051) (NM_009820); Sp7, forward (162–181) and reverse (453–472) (NM_130458); Twist2, forward (151–168) and reverse (680–698) (NM_007855); Bglap2, forward (22–41) and reverse (430–450) (NM_001032298); Col1a1, forward (1247–1268) and reverse (1498–1518) (X15896); Acp5, forward (123–144) and reverse (861–882) (NM_007388); Calcr, forward (883–903) and reverse (1749–1769) (NM_007588); Ctsk, forward (54–74) and reverse (639–663) (NM_007802); Tnfrsf11a, forward (143–162) and reverse (383–402) (NM_009399); and 18s rRNA, forward (2376–2395) and reverse (2507–2526) (X00686). PCR included an initial denaturation step at 94 C for 2 min followed by 30–40 cycles of 30 sec at 94 C, 30 sec at an annealing temperature ranging between 55 and 62 C depending on the primer pair, and 30 sec elongation at 68 C, followed by a final elongation step at 68 C for 2 min. To ensure specificity of the Tsha, Tshb, and Tshr RT-PCR products, Southern analysis was performed using internal oligonucleotide probes.

TSHR Antibodies

A human TSHR-stimulating monoclonal antibody (M22:IgG1,λ) (20,48) was used to stimulate primary osteoblasts and osteoclasts. A mouse TSHR antibody (3G4:IgG2b,κ) recognizing a linear TSHR epitope, is devoid of stimulating activity and served as a negative control (18,19). In all studies, M22 and 3G4 were used at dilutions of 1:1000 and 1:20, respectively.

Determination of cAMP Activity

cAMP activity was determined in osteoblasts and osteoclasts as described (49). Cells were washed and incubated in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) buffer (124 mm NaCl; 5 mm KCl; 1.25 mm MgSO4; 1.45 mm CaCl2; 8 mm glucose; 0.5 g/liter BSA; 25 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7.6) for 30 min at 37 C. Cells were incubated in KRH containing rolipram (25 μm) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min at 37 C with addition of forskolin (10 μm) (Sigma-Aldrich,), bTSH (10 or 100 U/liter), hTSH (10 or 100 U/liter), or TSHR antibody M22 or 3G4. In studies with M22, KRH was replaced with Hanks’ buffered medium (400 mg/liter KCl, 60 mg/liter KH2PO4, 350 mg/liter NaHCO3, 1000 mg/liter d-glucose, 20 mm HEPES, 222 mm sucrose, 15 g/liter BSA, 0.5 mm xanthine). After stimulation, cells were treated with 0.1 m HCl for 5 min, dried under vacuum, and stored at −80 C. The samples were suspended in 500 μl and assayed as described (49). The detection limit of the assay is 0.5 nm/liter.

Western Blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared from primary osteoblasts on d 14 and osteoclasts on d 9. Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl2, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin, and sonicated. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and supernatant proteins separated on a 4% stacking and 10% resolving polyacrylamide gel before transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated in nonfat dried milk (20%) in Tween-PBS (0.1%) at 25 C for 2 h, followed by incubation in nonfat dried milk (5%) in Tween-PBS (0.1%) containing 3G4 (1:50) at 4 C for 16 h. Antibody 3G4 recognizes a linear epitope common to mouse and rat TSHR (19). Membranes were washed in Tween-PBS (0.1%) and incubated with goat antimouse horseradish peroxidase 1:80,000 (Pierce UK, Cramlington, UK) for 1 h at 25 C before washing in Tween-PBS (0.1%). TSHR protein was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL system; Pierce UK).

Statistics

Normally distributed data were analyzed by Student’s t test or ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Frequency distributions of mineralization densities were compared using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, in which P values for the D statistic in 1024 pixel data sets were D > 6.01, P < 0.05; D > 7.20, P < 0.01; and D > 8.62, P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Grigoriadis for help with osteoclast cultures, M. Arora for help with SEM studies and bone resorption assays, and B. Rees-Smith for antibody M22.

Footnotes

These studies were supported by a Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinician Scientist Award (J.H.D.B.), Arthritis Research Council Training Fellowship (E.M., G.R.W.), Wellcome Trust Grant (G.W., J.H.D.B.), MRC Career Establishment Grant (G.R.W.), British Thyroid Foundation Grant (J.H.D.B., G.R.W.), Hammersmith Hospitals National Health Service Trust Grant (G.R.W., J.H.D.B.), Horserace Betting Levy Board Grant (A.B.), and National Institutes of Health Grants RR00055 and DK20595 (S.R., R.E.W.) and DK15070 (S.R.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 11, 2007

Abbreviations: BMD, Bone mineral density; bTSH, bovine TSH; BSE-SEM, backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy; BVF, bone volume fraction; HET, heterozygote hyt/+; HI-FBS, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum; hTSH, human TSH; HZ, hypertrophic zone; KRH, Krebs-Ringer-HEPES; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; P14, postnatal d 14; PZ, proliferative zone; qBSE-SEM, quantitative compositional BSE-SEM; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; RZ, reserve zone; T3/4, T3 and T4; TR, T3 receptor; TRAP, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; TSHR, TSH receptor.

References

- Kanis JA, Johnell O 2005 Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int 16:229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray NF, Chan JK, Thamer M, Melton 3rd LJ 1997 Medical expenditures for the treatment of osteoporotic fractures in the United States in 1995: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res 12:24–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosekilde L, Eriksen EF, Charles P 1990 Effects of thyroid hormones on bone and mineral metabolism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 19:35–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L 2002 Fractures in patients with hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism: a nationwide follow-up study in 16,249 patients. Thyroid 12:411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DC, Ettinger B, Nevitt MC, Stone LS 2001 Risk for fracture in women with low serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone. Ann Intern Med 134:561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Williams GR 2004 The thyroid and the skeleton. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 61:285–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe E, Marians RC, Yu W, Wu XB, Ando T, Li Y, Iqbal J, Eldeiry L, Rajendren G, Blair HC, Davies TF, Zaidi M 2003 TSH is a negative regulator of skeletal remodeling. Cell 115:151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassart G, Dumont JE 1992 The thyrotropin receptor and the regulation of thyrocyte function and growth. Endocr Rev 13:596–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marians RC, Ng L, Blair HC, Unger P, Graves PN, Davies TF 2002 Defining thyrotropin-dependent and -independent steps of thyroid hormone synthesis by using thyrotropin receptor-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:15776–15781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma B, Otten BJ, Stoelinga GB, Wit JM 1996 Catch-up growth after prolonged hypothyroidism. Eur J Pediatr 155:362–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivkees SA, Bode HH, Crawford JD 1988 Long-term growth in juvenile acquired hypothyroidism: the failure to achieve normal adult stature. N Engl J Med 318:599–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichsen S, Christ S, Heuer H, Schafer MK, Mansouri A, Bauer K, Visser TJ 2003 Regulation of iodothyronine deiodinases in the Pax8−/− mouse model of congenital hypothyroidism. Endocrinology 144:777–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RE, Chassande O, Koo EK, Macchia PE, Cua K, Samarut J, Refetoff S, Refetoff S 2002 Thyroid function and effect of aging in combined hetero/homozygous mice deficient in thyroid hormone receptors α and β genes. J Endocrinol 172:177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu WX, Du GG, Kopp P, Rentoumis A, Albanese C, Kohn LD, Madison LD, Jameson JL 1995 The thyrotropin (TSH) receptor transmembrane domain mutation (Pro556-Leu) in the hypothyroid hyt/hyt mouse results in plasma membrane targeting but defective TSH binding. Endocrinology 136:3146–3153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea PJ, Bassett JH, Sriskantharajah S, Ying H, Cheng SY, Williams GR 2005 Contrasting skeletal phenotypes in mice with an identical mutation targeted to thyroid hormone receptor α1 or β. Mol Endocrinol 19:3045–3059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea PJ, Guigon CJ, Williams GR, Cheng SY 2007 Regulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 by thyroid hormone: identification of a thyroid hormone response element in the murine Fgfr1 promoter. Endocrinology 148:5966–5976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens DA, Harvey CB, Scott AJ, O’Shea PJ, Barnard JC, Williams AJ, Brady G, Samarut J, Chassande O, Williams GR 2003 Thyroid hormone activates fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 in bone. Mol Endocrinol 17:1751–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costagliola S, Bonomi M, Morgenthaler NG, Van Durme J, Panneels V, Refetoff S, Vassart G 2004 Delineation of the discontinuous-conformational epitope of a monoclonal antibody displaying full in vitro and in vivo thyrotropin activity. Mol Endocrinol 18:3020–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costagliola S, Khoo D, Vassart G 1998 Production of bioactive amino-terminal domain of the thyrotropin receptor via insertion in the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor. FEBS Lett 436:427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J, Evans M, Premawardhana LD, Depraetere H, Jeffreys J, Richards T, Furmaniak J, Rees Smith B 2003 Human monoclonal thyroid stimulating autoantibody. Lancet 362:126–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JH, O’Shea PJ, Sriskantharajah S, Rabier B, Boyde A, Howell PG, Weiss RE, Roux JP, Malaval L, Clement-Lacroix P, Samarut J, Chassande O, Williams GR 2007 Thyroid hormone excess rather than thyrotropin deficiency induces osteoporosis in hyperthyroidism. Mol Endocrinol 21:1095–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballock RT, Zhou X, Mink LM, Chen DH, Mita BC, Stewart MC 2000 Expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in epiphyseal chondrocytes induced to terminally differentiate with thyroid hormone. Endocrinology 141:4552–4557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto JM, Fenton AJ, Holloway WR, Nicholson GC 1994 Osteoblasts mediate thyroid hormone stimulation of osteoclastic bone resorption. Endocrinology 134:169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Bellows CG, Aubin JE, Heersche JN 1995 Tri-iodothyronine (T3) and dexamethasone interact to modulate osteoprogenitor cell differentiation in fetal rat calvaria cell cultures. Bone 16:545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne M, Kang MI, Quail JM, Baran DT 1998 Thyroid hormone excess increases insulin-like growth factor I transcripts in bone marrow cell cultures: divergent effects on vertebral and femoral cell cultures. Endocrinology 139:2527–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy GR, Shapiro JL, Bandelin JG, Canalis EM, Raisz LG 1976 Direct stimulation of bone resorption by thyroid hormones. J Clin Invest 58:529–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi K, Ishida H, Nagata T, Yamauchi N, Tsurumi C, Nishikawa S, Wakano Y 1994 Thyroid hormone suppresses the differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells to osteoblasts, but enhances functional activities of mature osteoblasts in cultured rat calvaria cells. J Cell Physiol 161:544–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson H, Siebler T, Stevens DA, Shalet SM, Williams GR 2000 Thyroid hormone acts directly on growth plate chondrocytes to promote hypertrophic differentiation and inhibit clonal expansion and cell proliferation. Endocrinology 141:3887–3897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A, Gagnon A, Dods P, Papineau D, Tiberi M, Sorisky A 2002 TSH signaling and cell survival in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283:C1056–C1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas M, Santisteban P 2003 TSH-activated signaling pathways in thyroid tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 213:31–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz KL, Allgeier A, Offermanns S, Spicher K, Van Sande J, Dumont JE, Schultz G 1996 The human thyrotropin receptor: a heptahelical receptor capable of stimulating members of all four G protein families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:116–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann S, Hofbauer LC, Scharrenbach V, Wunderlich A, Hassan I, Lingelbach S, Zielke A 2004 Thyrotropin (TSH)-induced production of vascular endothelial growth factor in thyroid cancer cells in vitro: evaluation of TSH signal transduction and of angiogenesis-stimulating growth factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:6139–6145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park ES, Kim H, Suh JM, Park SJ, You SH, Chung HK, Lee KW, Kwon OY, Cho BY, Kim YK, Ro HK, Chung J, Shong M 2000 Involvement of JAK/STAT (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription) in the thyrotropin signaling pathway. Mol Endocrinol 14:662–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Park ES, Kim MS, Kim TY, Lee HS, Lee S, Jang IS, Shong M, Park DJ, Cho BY 2002 Involvement of the protein kinase C pathway in thyrotropin-induced STAT3 activation in FRTL-5 thyroid cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 194:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh JM, Song JH, Kim DW, Kim H, Chung HK, Hwang JH, Kim JM, Hwang ES, Chung J, Han JH, Cho BY, Ro HK, Shong M 2003 Regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt/protein kinase B, FRAP/mammalian target of rapamycin, and ribosomal S6 kinase 1 signaling pathways by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and stimulating type TSH receptor antibodies in the thyroid gland. J Biol Chem 278:21960–21971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamant F, Poguet AL, Plateroti M, Chassande O, Gauthier K, Streichenberger N, Mansouri A, Samarut J 2002 Congenital hypothyroid Pax8−/− mutant mice can be rescued by inactivating the TRα gene. Mol Endocrinol 16:24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu AM, Liao XH, Weiss RE, Millen K, Refetoff S 2006 Tissue-specific thyroid hormone deprivation and excess in monocarboxylate transporter (mct) 8-deficient mice. Endocrinology 147:4036–4043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlenz J, Maqueem A, Cua K, Weiss RE, Van Sande J, Refetoff S 1999 Improved radioimmunoassay for measurement of mouse thyrotropin in serum: strain differences in thyrotropin concentration and thyrotroph sensitivity to thyroid hormone. Thyroid 9:1265–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea PJ, Harvey CB, Suzuki H, Kaneshige M, Kaneshige K, Cheng SY, Williams GR 2003 A thyrotoxic skeletal phenotype of advanced bone formation in mice with resistance to thyroid hormone. Mol Endocrinol 17:1410–1424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard JC, Williams AJ, Rabier B, Chassande O, Samarut J, Cheng SY, Bassett JH, Williams GR 2005 Thyroid hormones regulate fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling during chondrogenesis. Endocrinology 146:5568–5580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett JH, Nordstrom K, Boyde A, Howell PG, Kelly S, Vennstrom B, Williams GR 2007 Thyroid status during skeletal development determines adult bone structure and mineralization. Mol Endocrinol 21:1893–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd G 1987 Atomic number and crystallographic contrast images with the SEM: a review of backscattered electron techniques. Mineralogical Magazine 51:3–19 [Google Scholar]

- Boyde A, Firth EC 2005 Musculoskeletal responses of 2-year-old Thoroughbred horses to early training. 8. Quantitative back-scattered electron scanning electron microscopy and confocal fluorescence microscopy of the epiphysis of the third metacarpal bone. NZ Vet J 53:123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyde A, Travers R, Glorieux FH, Jones SJ 1999 The mineralization density of iliac crest bone from children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Calcif Tissue Int 64:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebler T, Robson H, Shalet SM, Williams GR 2002 Dexamethasone inhibits and thyroid hormone promotes differentiation of mouse chondrogenic ATDC5 cells. Bone 31:457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ 1998 Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93:165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P, Hunziker E, Everts V, Jones S, Boyde A, Wehmeyer O, Suter A, von Figura K 2000 Functions of cathepsin K in bone resorption. Lessons from cathepsin K deficient mice. Adv Exp Med Biol 477:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J, Jeffreys J, Depraetere H, Evans M, Richards T, Kiddie A, Brereton K, Premawardhana LD, Chirgadze DY, Nunez Miguel R, Blundell TL, Furmaniak J, Rees Smith B 2004 Characteristics of a human monoclonal autoantibody to the thyrotropin receptor: sequence structure and function. Thyroid 14:560–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits G, Campillo M, Govaerts C, Janssens V, Richter C, Vassart G, Pardo L, Costagliola S 2003 Glycoprotein hormone receptors: determinants in leucine-rich repeats responsible for ligand specificity. EMBO J 22:2692–2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]