Abstract

The roles that T helper type 1 (Th1) and T helper type 2 (Th2) H. pylori specific immune responses play in protection from H. pylori challenge are poorly understood. It is expected that Th2 immune responses are required for protection against extracellular bacteria, such as H. pylori. However, recent studies have suggested that Th1 immunity is required for protection. The mechanisms by which this might occur are unknown. Our goal in this study was to more clearly define the effects of a Th1 vs. a Th2 promoting H. pylori vaccine on immunity and protection. Therefore, we tested a Th1 vaccine consisting of an H. pylori sonicate and CpG oligonucleotides (CpG) and a Th2 vaccine consisting of a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) depleted H. pylori sonicate combined with cholera toxin (CT). We demonstrate that although the Th2 promoting vaccine induced stronger systemic and local immune responses, only the Th1 promoting vaccine was protective.

Keywords: Th1, Th2, H. pylori, gastric immunity, vaccine, adjuvant

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative, extracellular, microaerophilic bacterium that colonizes the human gastric mucosa [1]. Infection is found worldwide, with prevalence as high as 90% in some developing countries [2, 3]. H. pylori infection commonly results in asymptomatic chronic gastritis, but 10–15% of those infected develop gastric ulcers or gastric cancer. Typically, H. pylori infection persists throughout the life of the host despite the presence of a robust immune response [4, 5]. In mice, vaccines have been developed that significantly reduce bacterial load, resulting in at least partial protection [6–9]. However, the immunological mechanisms that confer protection are not well understood.

H. pylori infection is atypical in that it causes a cellular infiltration of neutrophils and CD4 positive lymphocytes, as well as secretion of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ). This response is characteristic of a T helper type 1 (Th1) immune response, which is typically associated with intracellular pathogens [10–12]. This observation prompted early vaccine research to focus on the induction of T helper type 2 (Th2) immunity, since it was suspected that Th1 immunity prevented clearance from the host. Though some work supported this hypothesis [8], most studies suggest that in fact a strong Th1 biased environment, including increased gastritis, may be necessary for protection and clearance [13–15]. H. pylori vaccine studies using IL-4 knockout and B cell deficient mice have further supported this hypothesis, demonstrating that neither IL-4 nor antibody production (Th2 responses) are necessary for protection [13, 16]. Furthermore, studies have also shown that IL-12, a Th1 promoting cytokine, aids in protection [17]. While it is unclear how protection is achieved though Th1 mediated mechanisms, these studies suggest that a Th1 biased immune response may be necessary to control H. pylori infection.

We have previously demonstrated that H. pylori lipopolysaccharide (LPS) promotes Th1 immunity, and that the removal of LPS from an H. pylori vaccine results in strong Th2 immune responses [18]. However, many vaccine studies that focused on inducing Th2 immunity used an H. pylori sonicate preparation that contained H. pylori LPS [14, 19–21]. Thus, these studies using H. pylori sonicate may not have optimally induced Th2 biased H. pylori specific immunity. In this study, we sought to more clearly define the roles of Th1 and Th2 H. pylori specific immunity on protection against H. pylori challenge. Two groups of mice were immunized with either an H. pylori LPS containing sonicate and CpG oligonucleotide sequences (CpG) to promote strong Th1 immune responses, or an LPS depleted H. pylori sonicate and cholera toxin (CT) to promote strong Th2 immune responses. CpG sequences have been shown to be effective in promoting Th1 immunity through a variety of immunization routes, including oral immunization [22, 23]. Conversely, CT is commonly used to induce Th2 mucosal immunity [24, 25]. The Th1 and Th2 immune profiles were confirmed through a series of immunological assays followed by the evaluation of protection and induction of gastritis after immunization and challenge.

2. Results

2.1 H. pylori specific antibody titers from sera and local tissues before and after challenge

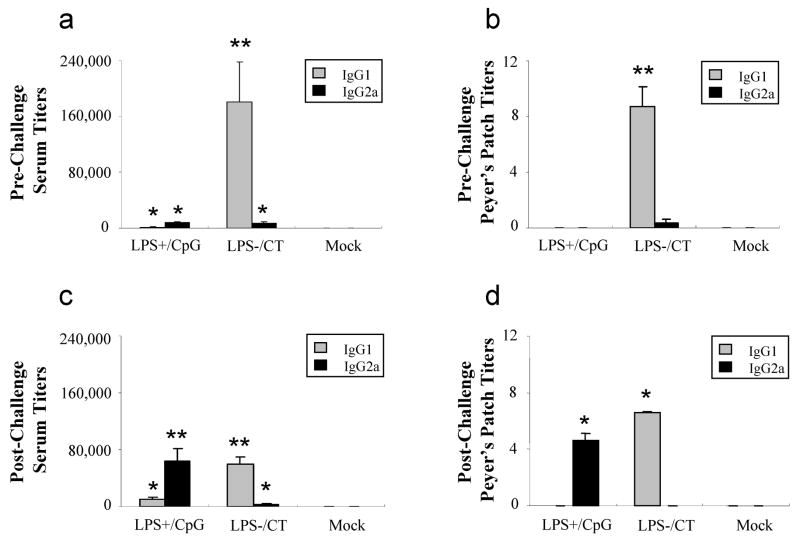

In mice, high titers of the IgG1 antibody isotype denote Th2 immunity, while high titers of the IgG2a antibody isotype reflect Th1 immunity [26]. H. pylori specific IgG1 and IgG2a isotypes were measured from sera and Peyer’s patches before and after challenge. Prior to challenge, IgG1 titers from both sera and Peyer’s patches were highest in the LPS−/CT immunized group and very low or undetectable in the LPS+/CpG immunized group (P<0.01) (Figs. 1a & 1b). IgG2a titers were low in sera and Peyer’s patches from both groups prior to challenge. Before challenge, IgG1 was less than IgG2a in sera and Peyer’s patches from the LPS+/CpG immunized mice, indicating a strong Th1 immune response. In the LPS−/CT immunized mice, IgG1 was greater than IgG2a, reflecting a strong Th2 immune response (Figs. 1a & 1b). After challenge, the Th1/Th2 profiles were even more prominent. Serum IgG1 titers remained highest in the LPS−/CT immunized group, while IgG2a serum titers significantly increased in the LPS+/CpG immunized group (P<0.01) (Fig. 1c). Similarly, immunization with LPS−/CT resulted in higher IgG1 titers than IgG2a titers in Peyer’s patches (P<0.05) (Fig. 1d). Conversely, immunization with LPS+/CpG resulted in higher IgG2a titers than IgG1 titers from Peyer’s patches (P<0.05) (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that the LPS+/CpG and LPS−/CT vaccines promote a Th1 and Th2 biased immune response, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Antigen specific IgG1 and IgG2a production from serum and mucosal lymphoid tissues. Mice (N=12) were immunized with either LPS containing H. pylori sonicate and CpG (LPS+/CpG) or LPS depleted sonicate and CT (LPS−/CT), followed by oral challenge with H. pylori. IgG1 and IgG2a antibody titers to H. pylori NAP are shown for serum and Peyer’s patches before (a, b) and after (c, d) H. pylori challenge. Titers were measured from mice seven days after the last immunization (prior to challenge) and seven days post-challenge. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is denoted by * indicating P<0.05 and ** indicating P<0.01 compared to controls.

2.2 Vaccine induced antigen specific cytokine responses after challenge

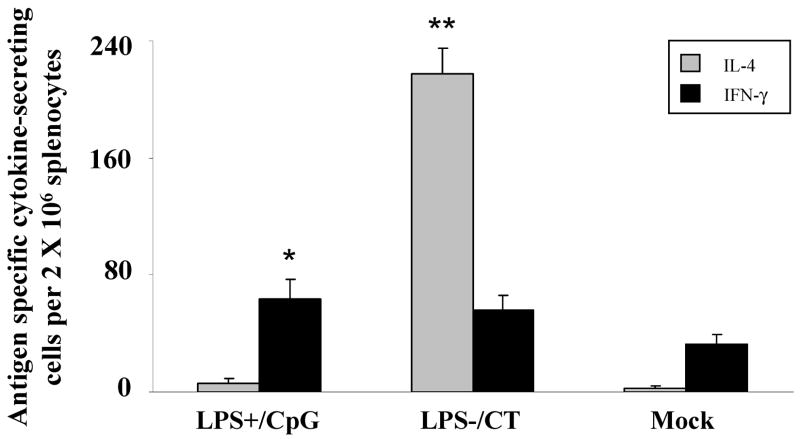

To confirm the Th1/Th2 polarizing effects of immunization with LPS+/CpG versus LPS−/CT vaccines, antigen specific cytokine production was measured after challenge. Although both immunization groups had increased numbers of IFN-γ secreting splenocytes, only mice immunized with LPS+/CpG secreted significantly more IFN-γ than the mock controls (P<0.05) (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in IFN-γ production between the LPS+/CpG and LPS−/CT groups. Conversely, the LPS−/CT group had a twenty-fold increase in H. pylori specific IL-4 secreting splenocytes compared to the LPS+/CpG group or the mock control group (P<0.01) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

IL-4 and IFN-γ antigen specific responses from immunized mice. Mice (N=12) were immunized with either LPS containing H. pylori sonicate and CpG (LPS+/CpG) or LPS depleted sonicate and CT (LPS−/CT), followed by oral challenge with H. pylori. Splenocytes were cultured with H. pylori sonicate and mean (± SEM) numbers of IL-4 (gray) and IFN-γ (black) secreting cells were measured by ELISPOT. Statistical significance is denoted by * indicating P<0.05 and ** indicating P<0.01 compared to controls.

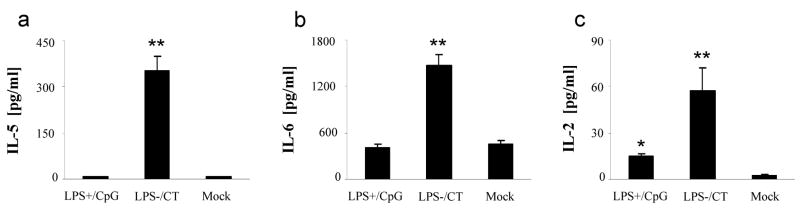

Antigen specific IL-5 and IL-6 production, as well as the lymphocyte growth factor IL-2, are of interest when evaluating inflammation and immunity, although they are not specifically associated with Th1 versus Th2 immune responses. Mice immunized with LPS−/CT produced significantly more IL-5 and IL-6 than either the LPS+/CpG immunized mice or the controls (P<0.01) (Fig. 3a & 3b). Both groups of immunized mice secreted significantly more IL-2 than controls (P<0.05) (Fig. 3c). However, mice immunized with LPS−/CT produced nearly twice as much IL-2 compared to the LPS+/CpG group (P<0.05).

Fig. 3.

IL-5, IL-6, and IL-2 antigen specific responses from immunized mice. Mice (N=12) were immunized with either LPS containing H. pylori sonicate and CpG (LPS+/CpG) or LPS depleted sonicate and CT (LPS−/CT), followed by oral challenge with H. pylori. Splenocytes were cultured with H. pylori sonicate and culture supernatants were used to measure (a) IL-5, (b) IL-6, and (c) IL-2 production by Luminex. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is denoted by * indicating P<0.05 and ** indicating P<0.01 compared to controls.

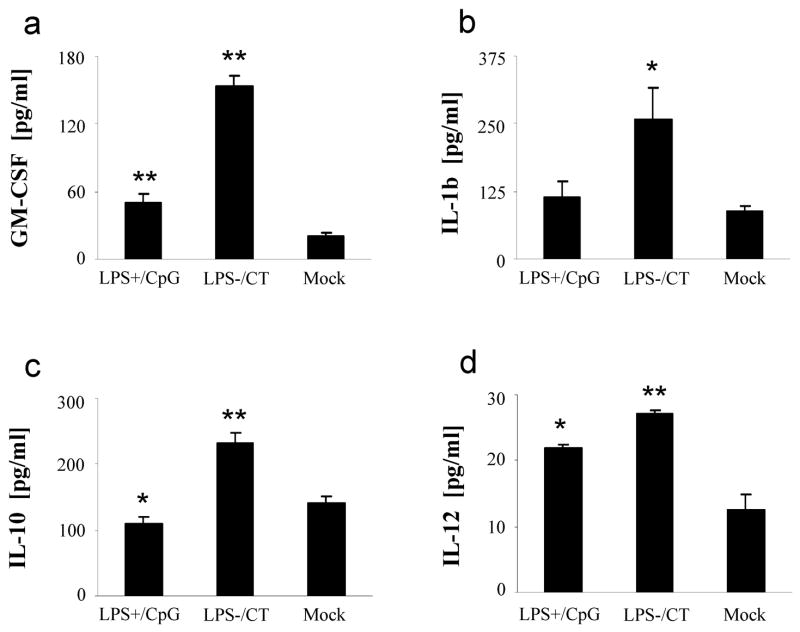

To more closely evaluate the correlation between the H. pylori specific Th1- and Th2-type responses and innate-type responses, a variety of innate-type cytokines were measured from splenocytes of immunized mice following challenge. While both groups of immunized mice produced significantly more GM-CSF compared to mock controls (P<0.01), mice immunized with LPS+/CpG produced half as much as those immunized with LPS−/CT (P<0.05) (Fig. 4a). Similarly, IL-1β production was higher in the LPS−/CT immunized mice than either the LPS+/CpG immunized mice or mock controls (P<0.05) (Fig. 4b). Splenocytes from mice immunized with LPS−/CT produced more IL-10 than mock controls, while mice immunized with LPS+/CpG produced less IL-10 than mock controls (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively) (Fig. 4c). Production of IL-12 was significantly higher in both groups of mice compared to mock controls (P<0.05), though the LPS−/CT group produced more IL-12 than the LPS+/CpG group (P<0.05) (Fig. 4d). Values for TNF-α were high in all groups after challenge, including mock controls (data not shown). Overall, these data show that H. pylori specific innate-type responses were higher in the LPS−/CT group than in the LPS+/CpG group.

Fig. 4.

GM-CSF, IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-12 responses from immunized mice. Mice (N=12) were immunized with either LPS containing H. pylori sonicate and CpG (LPS+/CpG) or LPS depleted sonicate and CT (LPS−/CT), followed by oral challenge with H. pylori. Splenocytes were cultured with H. pylori sonicate and culture supernatants were used to measure (a) GM-CSF, (b) IL-1β, (c) IL-10, and (d) IL-12 production by Luminex. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is denoted by * indicating P<0.05 and ** indicating P<0.01 compared to controls.

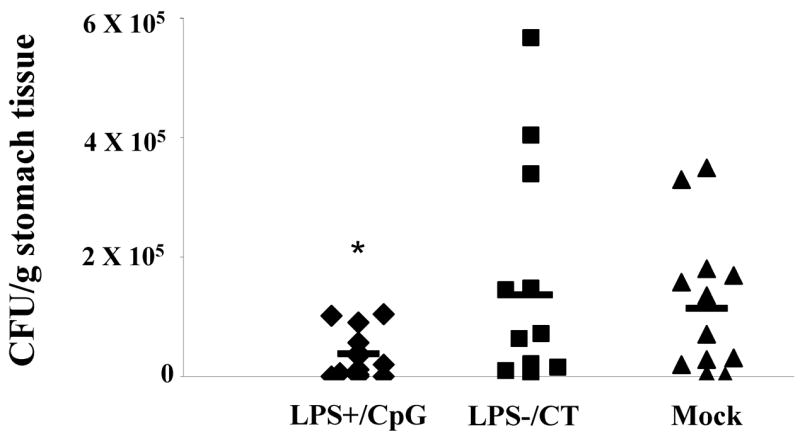

2.4 Protection against infection of the stomach with H. pylori SS1

Having determined antibody and cytokine responses, we next examined whether immunization with LPS+/CpG or LPS−/CT vaccine would protect against oral H. pylori challenge. One month after immunization, mice were challenged with three doses of 108 CFU of H. pylori SS1. Mice immunized with LPS+/CpG had a three-fold decrease in bacterial load compared to either the LPS−/CT immunized mice or the mock control group (P<0.05) (Fig. 5). Mice immunized with LPS−/CT did not show protection and in two animals the bacterial load was higher than that of any mock controls. Additionally, there were no significant differences in gastric pathology observed between the LPS+/CpG and the LPS−/CT (data not shown). These data demonstrate that immunization with a vaccine that promotes Th1 immunity is more protective against H. pylori challenge than a vaccine that promotes Th2 immunity.

Fig. 5.

Log10 CFU/gram of tissue obtained 8 days after challenged. Twelve mice were immunized with either LPS containing sonicate and CpG (LPS+/CpG) or LPS depleted sonicate and CT (LPS−/CT), followed by oral challenge one month later with 108 CFU H. pylori SS1. LPS+/CpG immunized mice had significantly fewer bacteria than LPS−/CT immunized mice or mock controls (P<0.05). Bars represent means of the group. Statistical significance is denoted by * indicating P<0.05 and ** indicating P<0.01 compared to controls.

3. Discussion

The H. pylori specific Th1/Th2 gastric immune profile is thought to be an influential factor in protection against H. pylori infection. Previous research in our laboratory has demonstrated a substantial role for H. pylori LPS in establishing Th1/Th2 immunity [27]. We showed that immunization with LPS-depleted H. pylori resulted in a Th2 biased immune response, whereas H. pylori sonicate containing LPS produced a Th1 immune profile when CT was used as an adjuvant. However, the mice were not challenged in that study and thus, the protective role of Th1 vs. Th2-type immunity was not defined. An H. pylori sonicate containing LPS, with either CT or heat-labile enterotoxin (LT), has normally been thought to induce Th2 immunity and reduce bacterial load in H. pylori vaccine studies [8, 19, 28]. However, in our study, we observed no reduction in bacterial load with a Th2 inducing, LPS−/CT vaccine (Fig. 5). This suggests that the presence of LPS in an H. pylori sonicate vaccine contributes to the reduction in H. pylori bacterial load.

The goal of this study was to more clearly define the roles of Th1 and Th2 H. pylori specific immunity with regard to protection after challenge. Th1 biased immune responses in mice are most commonly characterized by an elevation in IFN-γ relative to IL-4, and by an elevation of IgG2a relative to IgG1. By this standard, mice immunized with the LPS containing sonicate and CpG (LPS+/CpG) displayed a bias towards Th1 immunity, while the mice immunized with an LPS depleted sonicate and CT (LPS−/CT) shifted towards Th2 immunity. However, since other cytokine responses that are sometimes thought of as Th1 biased (e.g. IL-2 and IL-12) showed a different pattern, the Th1 versus Th2 dichotomy is undoubtedly oversimplified, even in mice [29, 30]. Mice immunized with LPS−/CT were not protected from challenge despite the presence of a diverse and robust H. pylori specific immune response. However, the LPS+/CpG immunized mice were significantly more protected from challenge when compared to mock controls. Although the magnitude of this effect was modest, it was within the range of that seen in some other studies of H. pylori immunization [14, 31, 32].

A previous study by Shi et al. reported protection against H. pylori challenge using whole cell sonicate and CpG sequences[14]. Protection was associated with high levels of IgG2a and IFN-γ and was abrogated in IFN- γ knockout mice, which is in agreement with our results and emphasizes the importance of Th1 immunity for protection against H. pylori. Although the role of Th1 immunity in H. pylori infection has been considered an enigma, since the organism is regarded as extracellular, accumulating evidence from studies in vitro [33–35] suggests that a least transient intracellular residence plays an important role in the H. pylori life cycle. Some have even suggested that H. pylori may be a facultative intracellular organism [36].

It has been previously suggested that protection against H. pylori is associated with the development of gastritis [37–39] and an IL-12 dependent Th1 immune response [17]. We observed only modest inflammation with no significant differences between the LPS+/CpG and the LPS−/CT groups. This may reflect our use of BALB/c mice, in which Helicobacter infection is known to produce a less marked inflammatory response [38, 40]. Although we found that the LPS−/CT immunized mice (unprotected) produced significantly more IL-12 than the LPS+/CpG immunized mice (protected) (Fig. 4d), the increase in IL-12 and other inflammatory cytokines may have been a result of the higher bacterial load.

While the LPS+/CpG group produced elevated IFN-γ and IgG2a responses after challenge, most innate-type and adaptive cytokine responses were greater in the LPS−/CT group. This might be related to suppression of immune responses by regulatory T (Treg) cells. Recent studies have shown that Treg cells can restrict memory CD8+ T cell responses and suppress inflammation [41, 42]. Furthermore, it has been shown that Treg cells express toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) and are activated by LPS [43]. Because there was a 30-fold decrease of LPS in the LPS−/CT vaccine than in the LPS+/CpG vaccine, it is possible that the interaction of Treg cells with LPS, while not affecting protection, may be responsible for the overall decrease in inflammatory responses seen in the LPS+/CpG (protected) group.

In summary, we used an H. pylori sonicate with or without LPS, together with CpG or CT, to drive immunity either towards a Th1 or a Th2 profile. The results showed that while the Th2 promoting vaccine (LPS−/CT) induced stronger systemic and local immune responses, protection from H. pylori challenge was achieved only with the Th1 promoting vaccine (LPS+/CpG).

4. Materials and methods

4.1 Animals

Specific pathogen (Helicobacter) free, 8–12 week old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Mice were housed in microisolator cages and provided with autoclaved food, water, and bedding. Mice were fed and watered ad libitum. All animals were housed under protocols approved by ALAAC and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis.

4.2 H. pylori cultures and vaccine preparation

Mouse-adapted H. pylori strain SS1 was subcultured on brucella agar for 48 hr prior to passage into brucella broth, both supplemented with 5% newborn calf serum. The liquid culture was harvested at mid-log phase (OD600 0.4–0.6) and pelleted by centrifugation for vaccine preparation. Pellets were resuspended in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and sonicated (Sonic Dismembrator 550, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) on ice with five 10-second pulses at an amplitude between 7 and 9. Protein was measured using a Coomassie blue protein concentration measurement assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA) at an OD of 595nm. H. pylori SS1 sonicate (LPS+) was used for both vaccination and immunoassays (Luminex and ELISPOT). To deplete lipopolysaccharide (LPS−), H. pylori sonicate was passed three times over Polymyxin B columns (Pierce Chemicals, Rockville, IL) as per manufacturer's instructions, and concentrated five-fold by centrifugation with Amicon Ultra filtering devices (Millipore, Billerca, MA). LPS content was measured using QCL-1000 Chromogenic LAL Kit (Camprex,Walkersville, MD) as per manufacturer's instructions. Final LPS concentration in LPS+ and LPS− was 1102 EU/ml and 41 EU/ml, respectively. Neutrophil activating protein (NAP), used in antibody detection assays, was provided by Chiron Corporation (Siena, Italy) and prepared as described [44]. For H. pylori challenge, liquid culture was harvested and adjusted to 108 CFU in 0.1ml of brucella broth per dose.

4.3 Immunizations, challenge, and experimental design

Two groups of 24 mice each were immunized with the LPS+/CpG or LPS−/CT vaccines three times orally followed by two times intramuscularly at 10-day intervals. Oral immunizations consisted of 100μg of LPS+ and 30μg CpG oligonucleotides (5′-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3′) (Th1 group) or 100μg of LPS− and 10μg CT (Sigma) (Th2 group). The oral vaccine was suspended in 0.5ml of 3% sodium bicarbonate, and administered by oral gavage. Intramuscular (IM) immunizations contained 10μg of LPS+ and 10μg CpG or 10μg of LPS− and 1μg CT, which was injected into the right thigh muscle. The Mock control group received three oral immunizations and two intramuscular immunizations of 3% sodium bicarbonate (oral) or PBS (IM), respectively. Serum was collected 7 days after the final immunization and 7 days after challenge. Twelve mice in each group were sacrificed 8 days after the final immunization and twelve mice were challenged one month after the last immunization and sacrificed 8 days later. Mice were challenged at two day intervals with three doses of 108 colony-forming units (CFU) of H. pylori SS1, suspended in 0.1 ml brucella broth and administered by oral gavage using a ball-end feeding needle. Mice were euthanized with an overdose of Nembutal sodium solution (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Peyer's patches, spleens, and stomachs were sterilely collected from all mice at the time of sacrifice.

4.4 Lymphocyte isolation

Spleens were processed individually while Peyer’s patches were pooled from groups of four mice. Tissues were ground through a screen mesh and red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer from spleen samples (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). Lymphocytes (~5 × 106/group) were isolated from gastric tissues by collagenase type II (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) digestion as previously published [45]. After 2mm samples were taken for histology, stomachs (12 pooled for each group) were homogenized and incubated in 20ml of 440U/ml collagenase II in complete RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen/Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini, Woodland, CA), 2mM glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, 10mM HEPES (all from Gibco) and 5 × 10−5 M 2-ME (Sigma) with shaking (200 RPM) for 20 mins at 37°C, for a total of three incubations. Gastric lymphocyte cell suspensions were washed, centrifuged, combined for each group, and passed through a 45μM filter. All lymphocytes were then resuspended at 2 × 107 cells/ml in complete RPMI with 10% FBS.

4.5 Antigen specific cytokine assays

Antigen specific IL-4 and IFN-γ responses from lymphocytes were measured using ELISPOT as previously described [46]. Briefly, 2 × 106 lymphocytes were added to polyvinyldifluoride plates (Millipore) precoated with rat anti-mouse IL-4 (Endogen, Woburn, MA) or rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (BD/Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and blocked with complete RPMI 10% FBS. Cells were then incubated with 50μg/ml of LPS containing H. pylori sonicate for 13 hr at 37°C. Following incubation, supernatants from all ELISPOT assay plates ware collected and frozen at −80° C for use in Luminex assays. Plates were washed with PBS/0.02% Tween-20 (PBS/Tween) and incubated at room temperature for 2 hr with biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-4 (Endogen) or biotinylated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (BD/Pharmingen) in PBS/Tween/0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Plates were washed and incubated with avidin-peroxidase (1 hr at 37°C), followed by DAB substrate in Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer for 15 min. Spots were counted by a Zeiss KS automatic ELISPOT reader. Remaining cytokines were detected by Luminex using 50μl of previously frozen cell culture supernatant. IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, and TNF-α levels were measured according to manufacturer’s instructions using a Beadlyte mouse multi-cytokine detection system 2 (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) and Luminex 100 (Luminex, Austin, TX). A minimum of 100 beads were read and data were analyzed by MasterPlexQT software (MiraiBio, Alameda, CA) using 5 parameter logistics.

4.6 Antigen specific antibody assays

H. pylori specific anti-NAP IgG1 and IgG2a titers were measured from both serum and cell culture supernatant from lymphocytes isolated as described above and cultured overnight in complete RPMI 10% FBS at 2 × 105 cells/ml. U-bottom 96-well ELISA plates (Nunc Maxisorp, Denmark) were coated with 10μg/well of recombinant NAP in PBS overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS/0.3% Tween-20 and then blocked with PBS/2% goat serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hr at 37°C. Serum samples were added at an initial dilution of 1:200 in duplicate, with 1:3 serial dilutions performed in PBS/2% goat serum. Cell culture supernatants were serially diluted 1:3 in PBS/2% goat serum. Plates were incubated for 1 hr at 37°C, and then washed in PBS/0.3% Tween-20. A 1:10,000 dilution of biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) was added to the plates for 1 hr at 37°C. Plates were washed and then incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (BD/Pharmingen) for 1 hr at 37°C. Plates were again washed, developed with tetramethylbenzidine (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersurg, MD) for 10 min, and stopped with 2 M HCl. The optical density of each well was measured at 450nm on a Vmax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

4.7 Quantitative H. pylori culture from gastric tissue

Stomachs were divided in half longitudinally, placed in 300ul of brucella broth, weighed, and homogenized using a sterile ground-glass pestle. Ten-fold serial dilutions were plated on brucella agar plates with 5% newborn calf serum and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 5–7 days. Identification of H. pylori was based on colony morphology, microscopy, and biochemistry. The colony forming units (CFU) per gram of gastric mucosa was calculated by enumerating colonies, adjusting for the dilution, and dividing by the tissue weight.

4.8 Histopathology

Gastric samples were taken from mice pre-challenge and post-challenge. Samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 microns, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), using standard protocols. A modification of the Sydney system was used for grading samples (on a scale of 0–3) for inflammation, activity, and atrophy.

4.9 Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was used to identify statistically significant differences using Microsoft Excel’s statistical analysis software program. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant A142081 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Giuseppe del Giudice and Paolo Ruggiero (NAP antigen and helpful discussion), Paul Luciw and Imran Khan (technical support and assay development), and Jennifer Huff (animal handling, technical support, and helpful discussion).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):449–90. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(15):1175–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Giudice G, Covacci A, Telford JL, Montecucco C, Rappuoli R. The design of vaccines against Helicobacter pylori and their development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:523–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser MJ, Chyou PH, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55(3):562–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell HM, Li YY, Hu PJ, Liu Q, Chen M, Du GG, et al. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori in southern China: identification of early childhood as the critical period for acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1992;166(1):149–53. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goto T, Nishizono A, Fujioka T, Ikewaki J, Mifune K, Nasu M. Local secretory immunoglobulin A and postimmunization gastritis correlate with protection against Helicobacter pylori infection after oral vaccination of mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67(5):2531–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2531-2539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchetti M, Rossi M, Giannelli V, Giuliani MM, Pizza M, Censini S, et al. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in mice by intragastric vaccination with H. pylori antigens is achieved using a non-toxic mutant of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) as adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16(1):33–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikewaki J, Nishizono A, Goto T, Fujioka T, Mifune K. Therapeutic oral vaccination induces mucosal immune response sufficient to eliminate long-term Helicobacter pylori infection. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44(1):29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Giudice G, Michetti P. Inflammation, immunity and vaccines for Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2004;9 (Suppl 1):23–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundgren A, Trollmo C, Edebo A, Svennerholm AM, Lundin BS. Helicobacter pylori-specific CD4(+) T cells home to and accumulate in the human Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Infect Immun. 2005;73(9):5612–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5612-5619.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Louis E, Franchimont D, Piron A, Gevaert Y, Schaaf-Lafontaine N, Roland S, et al. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) gene polymorphism influences TNF-alpha production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated whole blood cell culture in healthy humans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113(3):401–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto T, Kita M, Ohno T, Iwakura Y, Sekikawa K, Imanishi J. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in Helicobacter pylori infection. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48(9):647–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamradt AE, Greiner M, Ghiara P, Kaufmann SH. Helicobacter pylori infection in wild-type and cytokine-deficient C57BL/6 and BALB/c mouse mutants. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(6):593–7. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi T, Liu WZ, Gao F, Shi GY, Xiao SD. Intranasal CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide is a potent adjuvant of vaccine against Helicobacter pylori, and T helper 1 type response and interferon-gamma correlate with the protection. Helicobacter. 2005;10(1):71–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawai N, Kita M, Kodama T, Tanahashi T, Yamaoka Y, Tagawa Y, et al. Role of gamma interferon in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammatory responses in a mouse model. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):279–85. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.279-285.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garhart CA, Nedrud JG, Heinzel FP, Sigmund NE, Czinn SJ. Vaccine-induced protection against Helicobacter pylori in mice lacking both antibodies and interleukin-4. Infect Immun. 2003;71(6):3628–33. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3628-3633.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akhiani AA, Pappo J, Kabok Z, Schon K, Gao W, Franzen LE, et al. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection following immunization is IL-12-dependent and mediated by Th1 cells. J Immunol. 2002;169(12):6977–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor JM, Ziman ME, Huff JL, Moroski NM, Vajdy M, Solnick JV. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide promotes a Th1 type immune response in immunized mice. Vaccine. 2006;24(23):4987–94. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotloff KL, Sztein MB, Wasserman SS, Losonsky GA, DiLorenzo SC, Walker RI. Safety and immunogenicity of oral inactivated whole-cell Helicobacter pylori vaccine with adjuvant among volunteers with or without subclinical infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69(6):3581–90. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3581-3590.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeda K, Yamashiro T, Minoura T, Fujioka T, Nasu M, Nishizono A. Evaluation of therapeutic efficacy of adjuvant Helicobacter pylori whole cell sonicate in mice with chronic H. pylori infection. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46(9):613–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeremy AH, Du Y, Dixon MF, Robinson PA, Crabtree JE. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in the Mongolian gerbil after prophylactic vaccination. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(2):340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roman M, Martin-Orozco E, Goodman JS, Nguyen MD, Sato Y, Ronaghy A, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1-promoting adjuvants. Nat Med. 1997;3(8):849–54. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCluskie MJ, Davis HL. Oral, intrarectal and intranasal immunizations using CpG and non-CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as adjuvants. Vaccine. 2000;19(4–5):413–22. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu-Amano J, Kiyono H, Jackson RJ, Staats HF, Fujihashi K, Burrows PD, et al. Helper T cell subsets for immunoglobulin A responses: oral immunization with tetanus toxoid and cholera toxin as adjuvant selectively induces Th2 cells in mucosa associated tissues. J Exp Med. 1993;178(4):1309–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinaro M, Staats HF, Hiroi T, Jackson RJ, Coste M, Boyaka PN, et al. Mucosal adjuvant effect of cholera toxin in mice results from induction of T helper 2 (Th2) cells and IL-4. J Immunol. 1995;155(10):4621–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens TL, Bossie A, Sanders VM, Fernandez-Botran R, Coffman RL, Mosmann TR, et al. Regulation of antibody isotype secretion by subsets of antigen-specific helper T cells. Nature. 1988;334(6179):255–8. doi: 10.1038/334255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor JM, Ziman ME, Huff JL, Moroski NM, Vajdy M, Solnick JV. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide promotes a Th1 type immune response in immunized mice. Vaccine. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee A, Chen M. Successful immunization against gastric infection with Helicobacter species: use of a cholera toxin B-subunit-whole-cell vaccine. Infect Immun. 1994;62(8):3594–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3594-3597.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao W, Chen Y, Alkan S, Subramaniam A, Long F, Liu H, et al. Human T helper (Th) cell lineage commitment is not directly linked to the secretion of IFN-gamma or IL-4: characterization of Th cells isolated by FACS based on IFN-gamma and IL-4 secretion. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(9):2709–17. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gor DO, Rose NR, Greenspan NS. TH1–TH2: a procrustean paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(6):503–5. doi: 10.1038/ni0603-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keenan JI, Rijpkema SG, Durrani Z, Roake JA. Differences in immunogenicity and protection in mice and guinea pigs following intranasal immunization with Helicobacter pylori outer membrane antigens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003;36(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garhart CA, Heinzel FP, Czinn SJ, Nedrud JG. Vaccine-induced reduction of Helicobacter pylori colonization in mice is interleukin-12 dependent but gamma interferon and inducible nitric oxide synthase independent. Infect Immun. 2003;71(2):910–21. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.910-921.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amieva MR, Salama NR, Tompkins LS, Falkow S. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4(10):677–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aspholm M, Olfat FO, Norden J, Sonden B, Lundberg C, Sjostrom R, et al. SabA is the H. pylori hemagglutinin and is polymorphic in binding to sialylated glycans. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(10):e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, Luinetti O, Ventura U, Fiocca R, et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):1009–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubois A, Boren T. Helicobacter pylori is invasive and it may be a facultative intracellular organism. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(5):1108–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piotrowski J, Piotrowski E, Skrodzka D, Slomiany A, Slomiany BL. Induction of acute gastritis and epithelial apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(3):203–11. doi: 10.3109/00365529709000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakagami T, Vella J, Dixon MF, O’Rourke J, Radcliff F, Sutton P, et al. The endotoxin of Helicobacter pylori is a modulator of host-dependent gastritis. Infect Immun. 1997;65(8):3310–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3310-3316.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D’Elios MM, Appelmelk BJ, Amedei A, Bergman MP, Del Prete G. Gastric autoimmunity: the role of Helicobacter pylori and molecular mimicry. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10(7):316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohammadi M, Czinn S, Redline R, Nedrud J. Helicobacter-specific cell-mediated immune responses display a predominant Th1 phenotype and promote a delayed-type hypersensitivity response in the stomachs of mice. J Immunol. 1996;156(12):4729–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kursar M, Bonhagen K, Fensterle J, Kohler A, Hurwitz R, Kamradt T, et al. Regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells restrict memory CD8+ T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2002;196(12):1585–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raghavan S, Fredriksson M, Svennerholm AM, Holmgren J, Suri-Payer E. Absence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is associated with a loss of regulation leading to increased pathology in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;132(3):393–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caramalho I, Lopes-Carvalho T, Ostler D, Zelenay S, Haury M, Demengeot J. Regulatory T cells selectively express toll-like receptors and are activated by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 2003;197(4):403–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satin B, Del Giudice G, Della Bianca V, Dusi S, Laudanna C, Tonello F, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a protective antigen and a major virulence factor. J Exp Med. 2000;191(9):1467–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guadalupe M, Reay E, Sankaran S, Prindiville T, Flamm J, McNeil A, et al. Severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2003;77(21):11708–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11708-11717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vajdy M, Singh M, Ugozzoli M, Briones M, Soenawan E, Cuadra L, et al. Enhanced mucosal and systemic immune responses to Helicobacter pylori antigens through mucosal priming followed by systemic boosting immunizations. Immunology. 2003;110(1):86–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]