Abstract

The response of mammalian cells to SN1 DNA methylators depends on functional MutSα and MutLα. Cells deficient in either of these activities are resistant to the cytotoxic effects of this class of chemotherapeutic drug. Because killing by SN1 methylators has been attributed to O6-methylguanine (MeG), we have constructed nicked circular heteroduplexes that contain a single MeG-T mispair and have examined processing of these molecules by mismatch repair in nuclear extracts of human cells. Excision provoked by MeG-T is restricted to the incised heteroduplex strand, leading to removal of the MeG when it resides on this strand. However, when the MeG is located on the continuous strand, the heteroduplex is irreparable. MeG-T-dependent repair DNA synthesis is observed on both reparable and irreparable, 3’ and 5’ heteroduplexes as judged by [32P]dAMP incorporation. Labeling with [α-32P]dATP followed by a cold dATP chase has demonstrated that newly synthesized DNA on irreparable molecules is subject to re-excision in a reaction that is MutLα-dependent, an effect attributable to presence of MeG on the template strand. Processing of the irreparable 3’ heteroduplex is also associated with incision of the discontinuous strand of a few percent of molecules near the thymidylate of the MeG-T base pair. These results provide the first direct evidence for mismatch repair-mediated iterative processing of DNA methylator damage, an effect that may be relevant to damage signaling events triggered by this class of chemotherapeutic agent.

In addition to its roles in replication and recombination fidelity, the mammalian mismatch repair system has been implicated in the earliest steps of the cellular response to certain classes of DNA damage (1-4). MSH2, MSH6, MLH1 or PMS2 defects render mammalian cells resistant to the cytotoxic effects of several classes of antitumor drugs, including SN1 DNA methylators, 6-thioguanine, and cisplatin (reviewed in 2,4-6). Because genetic inactivation of these mismatch repair loci has also been implicated in tumor development (7-9), involvement of the repair system in the DNA damage response has implications for the treatment of mismatch repair deficient cancers.

The mismatch repair-dependent damage response has been most thoroughly studied for lesions produced by SN1 DNA methylators. The cytotoxicity of this class of compounds, which includes N-methyl N-nitrosourea (MNU), N-methyl N’-nitro N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG), temozolomide (8-carbamoyl-3-methylimidazo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazin-4(3H)-one), procarbazine (N-isopropyl-α-(2-methylhydrazino)-p-toluamide), and dacarbazine (5-(3,3-dimethyl-1-triazenyl)-1H-imidazole-4-carboxamide), is largely due to production of O6-methylguanine (MeG) (10,11), which can pair with either thymine or cytosine (12,13). MutSα (MSH2•MSH6 heterodimer) and MutLα (MLH1•PMS2 heterodimer) have been implicated in the earliest steps of the cellular response to SN1 methylators. Perhaps the most compelling evidence for this view has been provided by the finding that MutSα and MutLα act upstream of damage signaling kinases in response to methylator damage (14,15). ATR and ATM kinases have been implicated in these events (15-20). While both MeG-T and MeG-C lesions are recognized by MutSα and both are subject to MutSα-dependent processing in nuclear extracts, MeG-T is a considerably better substrate (14,21).

Two models, which are not mutually exclusive, have been proposed to explain the MutSα and MutLα-dependent damage response to DNA methylators. The futile cycling model posits that replication bypass of a template strand MeG produces a base pair anomaly that activates the mismatch repair system. Because excision-repair by this system is restricted to the new strand, the MeG cannot be removed. This would lead to iterative and futile turnover of the daughter strand, which is postulated to activate damage signaling (10,11). In the alternate model, recruitment of a damage recognition complex comprised of MutSα MutLα, and perhaps other activities to a MeG lesion in the absence of an excision-repair response is sufficient to trigger kinase activation (22). Although no direct evidence for either of these models currently exists, the finding that SN1 DNA methylators result in G2 arrest in the second cell cycle following exposure suggests that replication may be required to elicit the effect (10,23). While consistent with the futile turnover model, replication would also be required for production of an MeG-T base pair, which as noted above, is better recognized by MutSα than is MeG-C. In fact, several DNA polymerases have been shown to display a significant preference for incorporation of thymidylate opposite a template MeG (24-26).

To further clarify the nature of mismatch repair-dependent processing of SN1 methylator damage, we have constructed both reparable and irreparable nicked heteroduplex DNAs containing a single MeG-T base pair. Analysis of the fate of these DNAs in nuclear extracts has demonstrated that an irreparable heteroduplex molecule, containing MeG on the template strand, is subject to multiple rounds of excision. We have also observed that a small fraction of irreparable molecules are subject to cleavage on the incised strand near the mismatch in a manner that depends on functional MutLα.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, nuclear extracts, and reagents

Alkylguanine alkyltransferase-deficient derivatives of MLH1-/- HCT116 (HCT116 BBR) and MSH6-/- HCT15 (HCT15 BBR) (27) were generously provided by Lili Liu (Case Western Reserve University). HCT116 BBR, HCT15 BBR, and HeLa S3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% or 5% (HeLa S3) fetal bovine serum. Nuclear extracts (28) and recombinant human MutSα and MutLα (29,30) were prepared as previously described. Recombinant human alkylguanine alkyltransferase (AGT) and O6-benzylguanine (O6BG) were generously provided by Henry Friedman (Duke Medical Center). Restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs, T4 DNA ligase and RNase A from Roche.

Substrate synthesis and purification

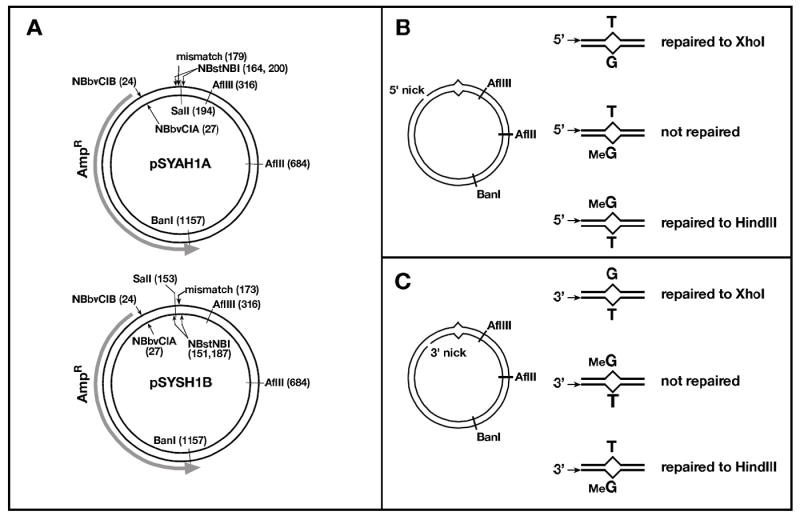

Plasmid pUC19Y (31), a gift from J. Hays (Oregon State University) was digested with SapI and AatII, the 1927 base pair (bp) fragment was gel-purified and ligated to one of two oligonucleotide cassettes containing HindIII and SalI sites. Plasmid pSYAH was constructed by ligation to the oligonucleotide duplex d(AGCCGTCGACTCCGATGCGGAAGCTTCGAGGACGGTAGCGAGAGACTCGACGT) annealed to d(CGAGTCTCTC↓GCTACCGTCCTCGAAGCTTCCGCATCGGAGTCGACG↓), which contains two N.BstNBI sites (underlined; location of nicking sites marked by ↓) on the antisense strand (defined as the transcribed strand of the β-lactamase gene and indicated as the outer or top strand in all figures). For plasmid pSYSH, the two N.BstNBI incision sites were placed on the sense strand (depicted as the inner or bottom strand in figures) by ligation of the 1927 bp pUC19Y fragment to the oligonucleotide cassette d(AGCGGAAGAGTCTCTC↓GCTACCGTCCTCGAAGCTTCCGCATCGGAGTCGACG↓T) hybridized to d(CGACTCCGATGCGGAAGCTTCGAGGACGGTAGCGAGAGACTCTTCC). pSYAH and pSYSH plasmids were digested with SspI, which cleaves approximately 150 bp from the HindIII site. The linearized plasmid was blunt end ligated to an oligonucleotide cassette containing a BbvCI site: d(TGGGATCCTCAGCATTATCG) and its complement. Resulting plasmids, pSYAH1A and pSYSH1B, contain a site for N.BbvCIB incision on the antisense strand 5’ to the HindIII sequence and an N.BbvCIA incision site on the sense strand 3’ to the HindIII site. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

pSYAH1A and pSYSH1B plasmids were used for preparation of G-T and MeG-T heteroduplexes, as well as control A•T homoduplex DNAs, by a strategy similar to that described by Wang and Hays (32). In a typical preparation, 400 μg (300 pmole) of plasmid were incubated with 1000 U of N.BstNBI for 2 hours at 55°C in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). After supplementation with an additional 400 U of enzyme and incubation for an additional hour, the reaction was terminated by addition of 30 nmoles of d(CGTCGACTCCGATGCGGAAGCTTCGAGGACGGTAGC) and heating at 82°C for 20 minutes. This inactivated the enzyme and melted out the 36mer between N.BstNBI nicking sites, which was prevented from rehybridizing to the gapped circle by the excess exogenous oligonucleotide. The gapped plasmid was separated from oligonucleotides using either Hipure columns (Roche, per manufacturer instructions) or by precipitation with 10% PEG8000. A 10-fold excess of synthetic 36-mer 5’d(pGCTACCGTCCTCGAXGCTTCCGCATCGGAGTCGACG) (X represents either G or MeG) was annealed to the gapped plasmid in T4 DNA ligase buffer (Roche) by heating to 80°C for 10 min and slow cooling to room temperature over an hour in a heating block. The reaction was supplemented with fresh 1 mM ATP and T4 DNA ligase (0.5 U/μg plasmid), and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours to overnight. Approximately 50% of the molecules were converted to a closed circular form, which was isolated by CsCl ethidium bromide equilibrium centrifugation.

Nicked circular heteroduplexes were prepared by digestion with 5 units of either N.BbvCIA or N.BbvCIB per μg plasmid for 1 hour at 37°C to generate a strand break 3’ or 5’ to the mismatch. Nicking was stopped by phenol extraction and substrate recovered by ethanol precipitation. For pSYAH1A derivatives, 3’ and 5’ nicks were located 152 or 155 bp from the mispair, respectively; corresponding values for pSYSH1B derivatives were 146 and 149 bp. Overall yield of nicked substrate from was typically 15-20% relative to starting material. As shown in Fig. 1, G-T or MeG-T mismatches resided within overlapping restriction sites for XhoI and HindIII. As judged by XhoI and HindIII sensitivity, heteroduplex preparations contained <10% homoduplex contamination. Nicked circular homoduplex DNAs were prepared either by the procedures outlined above, or by direct incision of pSYAH1A and pSYSH1B plasmid DNAs with N.BbvCIA or N.BbvCIB. No significant differences were observed between preparations obtained by the two methods.

Fig. 1.

- 5’-… AAGC[T]T CGAG…

- 3’-…TTCG [G]AGCTC …

In vitro mismatch excision and repair

HeLa extract containing endogenous AGT was diluted with one volume of 10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 110 mM KCl (to 12-18 mg/ml) and incubated with 25 μM O6BG for 30 minutes on ice prior to use in repair or excision reactions. When indicated, MeG-T heteroduplex DNA (100 ng) was pre-treated with AGT. Reactions (4 μl) contained 10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 400 fmoles of AGT, and 100 ng (77 fmoles) of heteroduplex. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, samples were chilled on ice prior to use. AGT treatment in this manner converted 80% of XhoI-resistant MeG-C heteroduplex to an endonuclease sensitive form (not shown). We attribute the residual 20% resistant form to presence of a contaminant in commercial MeG-containing oligonucleotide preparations. Similar contamination has been observed by others and has been attributed to incomplete deprotection of the modified guanine (33).

Mismatch-provoked excision was performed as described (30,34) with minor modifications. Reactions (20 μl) contained 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 110 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM ATP, 1 mM glutathione, 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 100 ng substrate DNA and 100 μg of nuclear extract. Components were assembled on ice and excision initiated by transfer to 37°C. Reactions were terminated after 5 min by addition of 30 μl of stop solution (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 mg/ml Proteinase K, 25mM EDTA, 0.4% SDS, 0.2 mg/ml glycogen). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 15-30 minutes, extracted twice with phenol and precipitated with ethanol. Recovered DNA was resuspended in 5 μl 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and digested with 2U each of BanI and SalI and 1μg RNase A before analysis on a 1.2% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml EtBr for 100 Vhrs. Excision was scored by quantifying the DNA fraction resistant to SalI, which cleaves 15 bp from the mismatch.

Mismatch repair reactions were performed in a similar manner except that 100 μM dNTPs were included, reactions were stopped after 15 minutes and recovered DNA was digested with BanI and XhoI (to score repair to G•C) or BanI and HindIII (to score repair to A•T). Use of the recommended buffer for HindIII (New England Biolabs buffer 2) resulted in cleavage of about 50% of MeG-T heteroduplex. Since this sensitivity was reduced to <10% by treatment with AGT, HindIII is apparently capable of cleaving a recognition site that contains MeG-T in place of the canonical A•T base pair. This problem was obviated (90-95% resistance) by performing HindIII digests (2U enzyme/100 ng DNA, 37°C for 1 hour) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9) 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 1 mM DTT, which was used for the experiments described here.

Label-chase analysis

Label-chase reactions (20 μl) with 5’ substrates were performed as described above, except that dNTP composition was 50 μM dCTP, dTTP and dGTP, 1 μM dATP and 10 μCi of [α32P]dATP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin Elmer). After 5 minutes at 37°C, a 6 μl sample was removed and quenched by addition to 10 μl of stop solution as above. The remainder of the reaction was immediately supplemented with 1.5 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA (control) or 10 mM unlabeled dATP (chase). Additional samples were removed at 15 and 30 minutes and reactions terminated as above. Quenched samples were incubated for 30-60 minutes at 37°C and DNA recovered as described above. DNA products were digested with N.BbvCIB and AflII and subjected to electrophoresis through 1% alkaline agarose 360 V-hr. Gels were dried onto DEAE paper (Whatman) and radioactivity quantified by phosphorimager analysis using IQMac software (GE Healthcare). For presentation here, line graphs are offset slightly along the X-axis to facilitate visual comparison.

Label-chase analysis using 3’ substrates was performed in a similar manner except that cold dATP chase was initiated after 15 minutes incubation at 37°C, and reactions done using HCT116BBR extracts were supplemented with 250 fmol MutLα as indicated. After digestion with N.BbvCIA, AflIII, AflII and BanI, DNA products were analyzed by electrophoresis through 8% polyacrylamide in 89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, 7 M urea (pH 8.0). Gels were dried and analyzed by phosphorimager as above.

Indirect end-labeling of 3’ repair products

Mismatch repair reactions were performed in the presence of unlabeled 100 μM dNTPs and DNA products were recovered as described above. Samples were digested with NlaIII before separating on an 8% polyacrylamide-urea gel as above. DNA was transferred to Hybond N+ using a semidry electrotransfer apparatus (Owl Scientific) at 200 mA for 15-30 minutes per manufacturers instructions. The membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (6X SSC, 5X Denhardts, 0.5% SDS) for one hour at 45°C before addition of oligonucleotide a136 d(CCGCGCACATTTCCCCGAAAAGTG), which had been end-labeled with 32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Following phosphorimager analysis, the blot was stripped by three 20-min washes with 0.1% SDS, 0.2 M NaOH at 68°C. The membrane was then blocked again and reprobed with end-labeled oligonucleotide s149 d(CACTTTTCGGGGAAATGTGCGCGG).

RESULTS

Excision and repair on MeG-T substrates

The nicked heteroduplexes used in this study, constructed using a previously published strategy (14,32), contained a single mispair, (G-T, T-G, MeG-T, or T-MeG; in the notation used here, the first base of the mismatch corresponds to that on the continuous DNA strand, which serves as template for repair) positioned within overlapping HindIII and XhoI sites to allow detection of repair to either A•T or G•C (Fig. 1). The strand break in these molecules was located approximately 150 bp either 3’ or 5’ to the mismatch, as viewed along the shorter path in the circular DNAs.

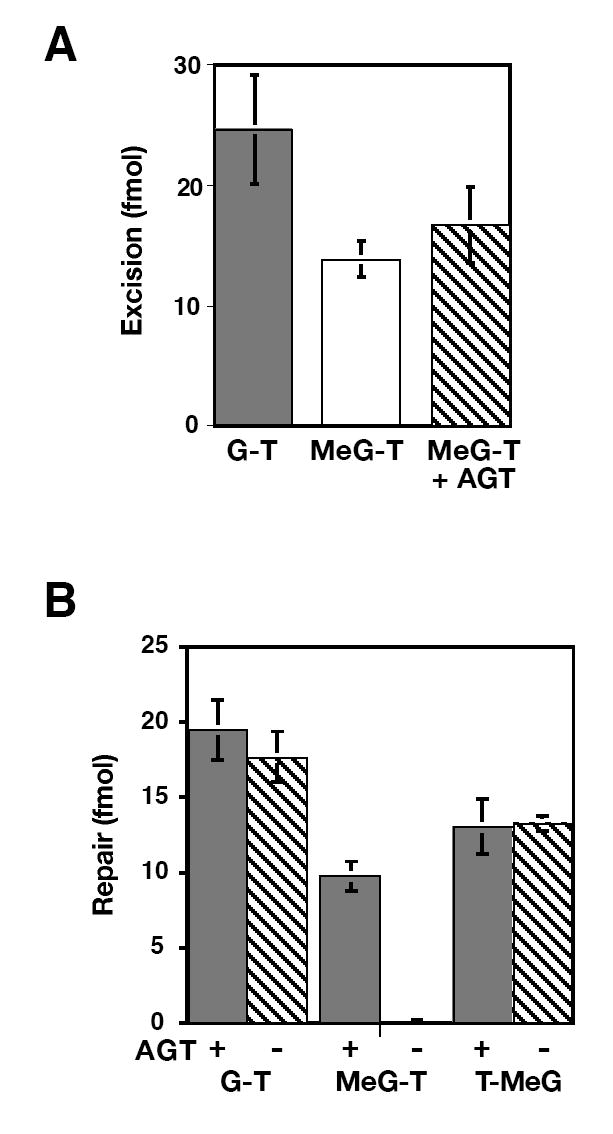

Mismatches containing MeG activate the mismatch repair system in nuclear extracts (14). However, when MeG resides on the continuous strand of a nicked heteroduplex, the lesion is not expected to be removed because mismatch-provoked excision is restricted to the incised heteroduplex strand (34). This issue is addressed in Fig. 2 using HeLa nuclear extract, which was pretreated with O6BG to inactivate endogenous AGT. As shown in panel A, G-T and MeG-T heteroduplexes were subject to mismatch-provoked excision in nuclear extract, as was the MeG-T heteroduplex from which the O6-methyl group was removed by pretreatment with AGT. G-T and T-MeG mismatches were also efficiently repaired to G•C or T•A base pairs, respectively, as judged by conversion to XhoI or HindIII sensitivity, and production of these products was unaffected by AGT pretreatment (panel B). However, the MeG-T heteroduplex was not subject to detectable repair under these conditions, but was corrected to G•C provided that the heteroduplex was pretreated with AGT (panel B).

Fig. 2.

An irreparable MeG-T mismatch provokes excision in HeLa nuclear extract. (A) Mismatch-provoked excision in O6BG-treated HeLa nuclear extract was scored by conversion of 5’ G-T or 5’ MeG-T heteroduplexes to a form resistant to SalI (cleavage site 15 bp from mismatch) as described in Materials and Methods. The MeG-T heteroduplex was pretreated with AGT as indicated. Results are the average of at least 3 determinations ± one standard deviation. (B) 5’ G-T, MeG-T or T-MeG heteroduplexes, which were pretreated or untreated with AGT as indicated, were subjected to mismatch repair in HeLa extract (Materials and Methods). Repair was scored by conversion to XhoI (G-T and MeG-T) or HindIII (T-MeG) sensitivity. Results represent the average of at least 3 experiments ± one standard deviation.

Repair tract labeling and turnover of newly synthesized DNA on a 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex

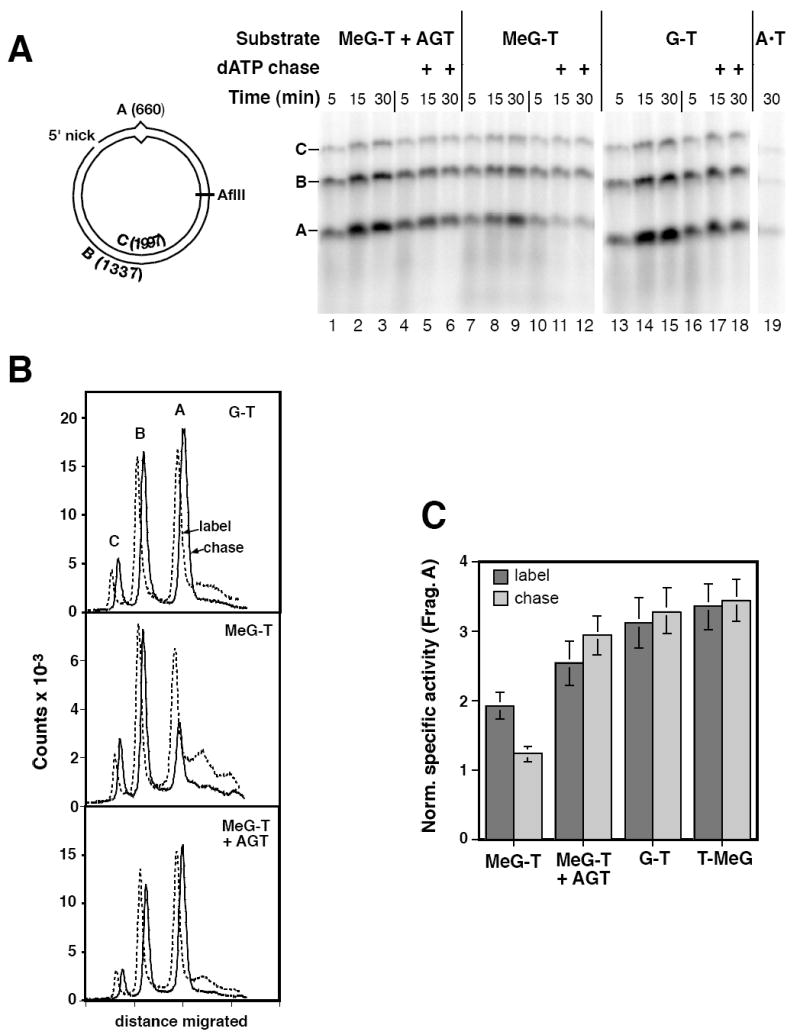

Radiolabeling with α-32P nucleotides was used to visualize DNA synthesis associated with mismatch repair. In agreement with previous studies (28,35,36), repair synthesis occurring on a nicked circular DNA in nuclear extract was dependent on presence of a mismatch within the molecule (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3, 9, and 15 with lane 19). Analysis of this effect with a G-T heteroduplex showed synthesis to be MutSα-dependent and demonstrated that a 660-nucleotide segment of the incised strand that spans the mispair (fragment A) was labeled to a specific activity 3 times that of the 1337-nucleotide remainder of the strand (fragment B; Supplemental Fig. 1), and synthesis was strongly biased to the incised strand. For G-T and MeG-T heteroduplexes, isotopic labeling of the nicked strand exceeded that of fragment C, which corresponds to the full-length continuous strand, by a factor of 10 or more (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Iterative excision occurs on a 5’ heteroduplex that contains MeG on the template strand for repair. (A) Reactions in O6BG-treated HeLa extract contained 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex, AGT-treated MeG-T heteroduplex, G-T heteroduplex, or A•T homoduplex as indicated, and were performed the presence of [α-32P]dATP under label-chase conditions (Materials and Methods). Reactions were sampled at 5, 15 and 30 min and quenched. Immediately after removal of the 5 min sample, the remainder of the reaction was supplemented with either buffer (lanes 2, 3, 8, 9, 14, and 15) or a large excess cold dATP (lanes 5, 6, 11, 12, 17, and 18) and incubation continued prior to removal of 15 and 30 min samples. Recovered DNA was digested with N.BbvCIB to reintroduce the 5’ nick, as well as AflII. Digests were analyzed by electrophoresis through alkaline agarose and radiolabel visualized and quantitated using a phosphorimager. A representative experiment is shown. As indicated in the diagram, band C corresponds to the 1997 nucleotide, full length linear form of the template strand; fragment B is a 1337 nucleotide segment derived from the incised strand extending from the N.BbvCIB nick to AflII site; and band A, which spans the mispair, corresponds to the shorter segment of the incised strand from the N.BbvCIB nick to AflII site. (B) Quantitative phosphorimager label-chase data shown for the G-T mismatch (panel A, lanes 16 and 17), AGT-treated MeG-T heteroduplex (panel A, lanes 4 and 5), and the MeG-T substrate (panel A, lanes 10 and 11). Results shown correspond to 5 min labeling (dashed lines) and after a subsequent 10 min chase (solid lines). Dashed and solid curves are offset horizontally to facilitate visualization. Although not shown, results after 10 and 25 min of chase were essentially identical. (C) Fragment specific activities were estimated as the quotient of the label in the species divided by fragment length. The normalized specific activity of fragment A was calculated relative to that of fragment B, which lacks a mispair. Results shown are the average values for this parameter (± one standard deviation) from at least 3 experiments after 5 min of labeling (dark gray bars) and after a subsequent 10 min cold chase (stippled bars).

The kinetics of repair synthesis on the irreparable 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex differed from those observed with the G-T substrate or the MeG-T heteroduplex that had been demethylated with AGT. While repair synthesis on the latter reparable DNAs was complete or nearly so within 15 min, synthesis on the MeG-T heteroduplex was slower and ongoing throughout the 30 min period tested (Fig. 3A, compare the labeling of fragment A, which spans the mismatch, in lanes 7-9 with that in lanes 1-3 and 13-15; Supplemental Fig. 2). For all three DNAs, labeled material smaller than fragment A (< 660 nucleotides) was evident; however, the fraction of total label present in this material was elevated in repair products from the MeG-T heteroduplex (Fig. 3A; also see Fig. 3B, dashed lines).

The irreparable 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex was also distinguished from the G-T and AGT-treated MeG-T DNAs in terms of the stability of repair DNA synthetic tracts, which was evaluated by labeling with [α-32P]dATP for 5 min and then chasing for 10 or 25 min with a 1000-fold excess of cold dATP (Fig. 3A). For the 5’ G-T heteroduplex, isotopic incorporation into fragments A, B, and C was stable to a 10 min chase (Fig. 3B top). However, label in DNA smaller than fragment A was reduced substantially during the chase, suggesting that this material represents intermediates produced during the course of repair synthesis. The irreparable 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex behaved differently (Fig. 3B center). While label in fragments B and C was largely resistant to chase, label in fragment A, which spans the mispair, was not, with a substantial fraction turning over during a 10 min chase. Because the MeG-T lesion in the irreparable heteroduplex activates excision (Fig. 2), production of full length fragment A during the 5 min labeling period indicates bypass of the template MeG by repair DNA synthesis. Subsequent turnover of this labeled material therefore implies occurrence of an iterative repair/excision process, a presumed consequence of persistence of MeG on the template strand in the 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex. Importantly, pretreatment of the MeG-T heteroduplex with AGT completely eliminated this chase effect (Fig. 3B bottom), proving that it is a consequence of the MeG lesion.

While fragment A label was stable to chase for the G-T, AGT-pretreated MeG-T, and T-MeG heteroduplexes, about 35% of that associated with the MeG-T heteroduplex was consistently turned over (Fig. 3C). The extent of fragment A turnover observed with the 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex was essentially independent of the whether the cold dATP chase was begun at 5, 10 or 15 minutes after initiation of the repair reaction (data not shown). Furthermore, DNA synthesis occurring on the MeG-T heteroduplex was greatly reduced, especially during the early stage of the reaction, if both strands of the circular substrate were covalently continuous (Supplemental Figure 3). We therefore attribute the interative excision observed to events occurring on a subset of molecules that retained a strand discontinuity during incubation in nuclear extract. Indeed, an iterative excision mechanism would be expected to inhibit ligation, and this was confirmed to be the case. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 4A, ligation of the 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex was retarded as compared to 5’ G-T, AGT-pretreated MeG-T, or T-MeG heteroduplexes. Whereas only 40% of 5’ G-T, AGT-pretreated MeG-T, or T-MeG heteroduplexes remained unligated after 5 min incubation in nuclear extract, about 70% of MeG-T heteroduplexes retained a strand discontinuity during this period, and this differential persisted upon further incubation. Thus, the finding that about 35% of the MeG-T fragment A label was turned over during chase implies that at least half of those molecules capable of being processed by the mismatch repair system were subject to interative excision.

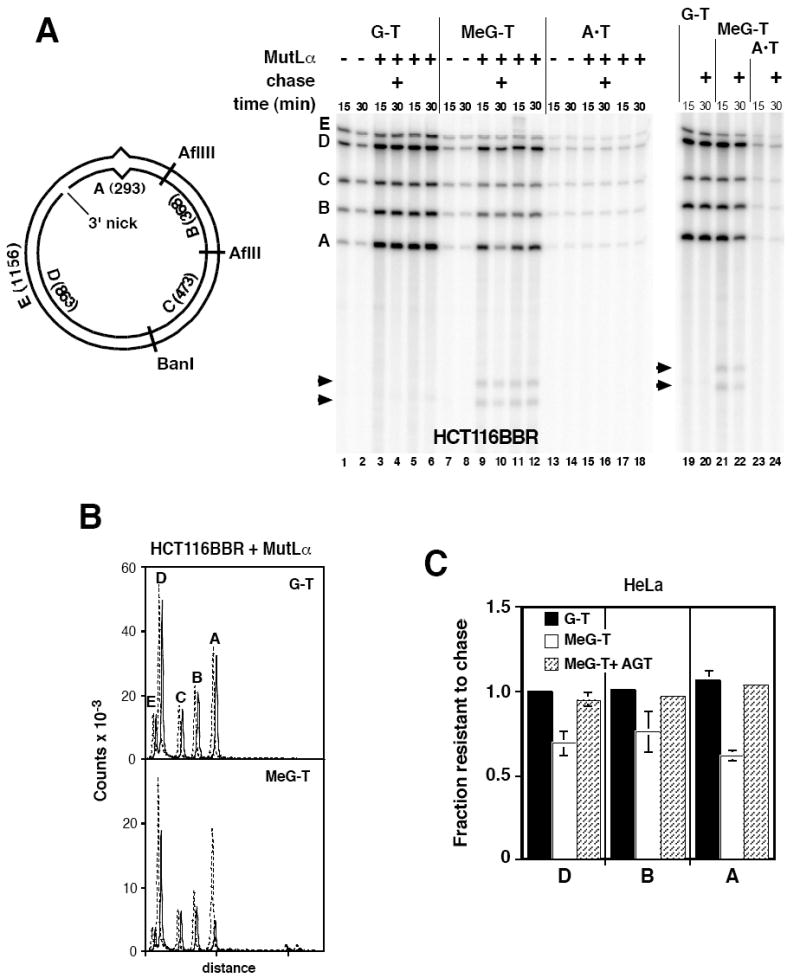

Processing of a 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex

Mismatch repair in nuclear extracts of human cells can be directed by a strand break located either 3’ or 5’ to the mispair (34). The polarity of DNA synthesis dictates that excision and repair synthesis occurring on an irreparable 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex will regenerate a 3’-substrate. Because one round of excision and repair synthesis on an irreparable 5’-heteroduplex is expected to yield a strand discontinuity 3’ to the mispair, 3’-directed processing of a MeG-T heteroduplex is of particular interest. In MutLα-deficient HCT116BBR nuclear extract, DNA synthesis was limited on both homoduplex and heteroduplex DNAs. Synthesis that did occur in the absence of MutLα was biased to the nicked strand but displayed no preference for the region of the heteroduplex that contained the mispair (Fig 4A, lanes 1, 2, 7, 8, 13 and 14; Supplemental Fig. 5). Although MutLα supplementation had no significant effect on background DNA synthesis occurring on the 3’ A•T control homoduplex (Fig. 4A lanes 13 - 18), synthesis on 3’ G-T and MeG-T heteroduplexes was enhanced substantially (compare lanes 3 - 6 with 1 and 2; and lanes 9 - 12 with 7 and 8). Enhanced synthesis was strongly biased to the incised heteroduplex strand (compare the sum of label in fragments A and D with that present in fragment E), and fragment A, which spans the mispair, was labeled to the highest specific activity, although labeling of fragments B and D was also elevated (Supplemental Fig 5). Similar mismatch-dependent labeling of these fragments was observed in HeLa nuclear extract (Fig. 4A lanes 19 - 24).

Fig. 4.

Iterative excision occurs on a 3’ MeG-T irreparable heteroduplex. (A) Nuclear extracts from HCT116BBR or O6BG-treated HeLa cells were incubated with 3’ substrates and dNTPs including [α-32P]dATP under label-chase conditions (Materials and Methods) in the absence or presence of exogenous 25 nM MutLα. After 15 min, a sample was removed and quenched. The remainder of the reaction was supplemented with excess cold dATP and incubation continued for an additional 15 min prior to termination (30 min sample). After cleavage with AflII, AflIII, and BanI, and nicking with N.BbvCIA, recovered DNA was analyzed on polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 7 M urea. Identity and sizes of DNA fragments are shown in the diagram. Note that fragment E is derived exclusively from the continuous heteroduplex strand, while fragments A and D are derived solely from the incised strand. Arrowheads indicate two novel fragments produced on the 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex. (B) Quantitative phosphorimager label-chase results obtained with MutLα-supplemented HCT116BBR extract are shown. These traces correspond to lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10 of panel A. Dashed (15 min label) and solid lines (15 min label, 15 min chase) are offset for presentation. (C) Quantitative results are shown for label-chase experiments performed in HeLa nuclear extract. Normalized specific activities were calculated relative to that of fragment C, and the fractional specific activity resistant to chase calculated. Because fragment C was used to correct for variation in DNA loading, the value of this parameter for fragment C was 1 in all cases. Values shown are the average (± one standard deviation) for three determinations for 3’G-T and 3’ MeG-T heteroduplexes. Results for AGT-treated 3’ MeG-T DNA are the mean of two determinations, with range of these two values indicated.

A 15 min labeling with [α-32P]dATP followed by a 15 min chase with excess cold dATP was employed to assess stability of repair DNA synthesis tracts on 3’-heteroduplexes. Repair synthesis tracts on the 3’ G-T heteroduplex were stable to chase in both MutLα-supplemented HCT116BBR and HeLa extracts (Fig. 4 panels B and C). By contrast, re-excision was readily apparent with the MeG-T heteroduplex, occurring primarily in fragment A, but also in adjacent fragments B and D (Fig. 4B bottom panel and Fig. 4C). This effect was abolished by prior treatment of the MeG-T substrate with AGT. As observed with the 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex described above, about 30 – 40% of label incorporated into the 3’ MeG-T substrate was subject to re-excision (Fig. 4C) and ligation was retarded in a manner that depended on MutLα and presence of MeG in the template DNA strand (Supplemental Fig. 4 panels B and C).

An unexpected finding with the 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex was the production of two small fragments, which were observed in HeLa and MutLα-supplemented HCT116BBR nuclear extracts (arrowheads Fig. 4A). Restriction digestion (not shown) indicated these two species were derived from fragment A and comprised about 4% of total label incorporated into fragment A. Labeling of both fragments implies that they can be generated after excision and resynthesis, suggesting two potential modes of origin: stalling of a subset of repair synthesis events at that template MeG accompanied by re-initiation of DNA synthesis on the distal side of the lesion; or occurrence of a single-or double-strand endonucleolytic event near the MeG-T mismatch.

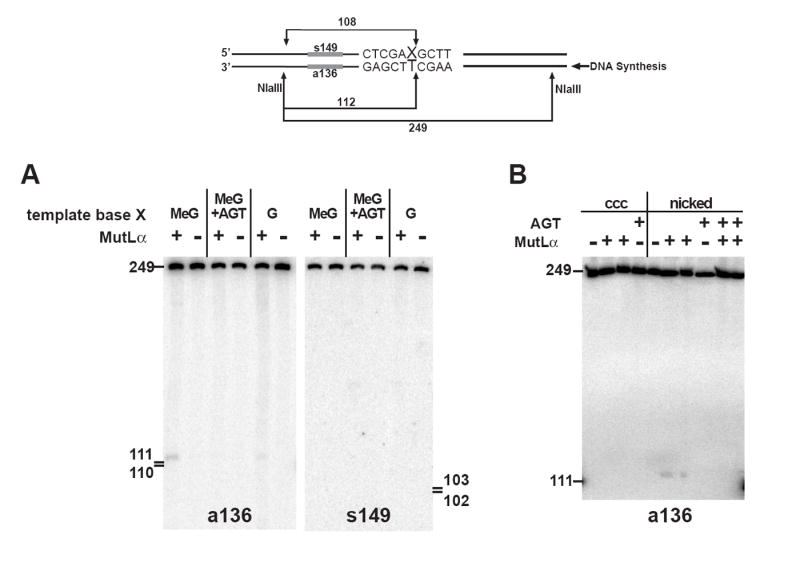

To eliminate the detection bias introduced by the labeling protocol, DNA products were analyzed by a blotting procedure using hybridization probes specific for each heteroduplex strand near the MeG-T lesion. As shown in Fig. 5A, this approach demonstrated presence of a discontinuity at or near the thymidylate of MeG-T mismatch, without a corresponding break in the other strand of the helix. Production of this discontinuity occurred on 1 - 2% of the molecules, was MutLα-dependent and abolished by pretreatment of the heteroduplex with AGT. NaOH or RNase A treatment of DNA products prior to electrophoretic analysis did not alter the size nor the yield of the radiolabeled fragments (not shown). Taken together, these findings are most consistent with an endonucleolytic event occurring near the thymidylate of the MeG-T mispair, but the molecular events leading to putative incision in this manner are uncertain. The role of the mismatch repair system in this effect is not clear, but it is noteworthy that use of a covalently closed circular MeG-T heteroduplex reduced the efficiency of incision in this manner (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the apparent yield of the incised species was reduced substantially with a 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex as compared with that observed with the 3’ MeG-T substrate (not shown). The latter reduction may be indicative of fundamentally different modes of repair complex assembly on 5’ and 3’ heteroduplexes. In fact, evidence for differential involvement of MutLα and PCNA in 3’- as opposed to 5’-directed mismatch repair is available, both in nuclear extract and purified systems (30,37-39).

Fig 5.

Localization of the site of MutLα-dependent incision of a MeG-T heteroduplex. (A) HCT116BBR nuclear extract was incubated with the indicated 3’ heteroduplexes for 15 min under repair conditions (Materials and Methods) in the absence or presence of 25 nM MutLα. Recovered DNA was digested with NlaIII, reactions products resolved on a 7 M urea polyacrylamide gel and transferred to HybondN+, which was probed with a 5’-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to the nicked strand (a136). After stripping, the membrane was reprobed with oligonucleotide s149, complementary to the template strand. (B) Reactions were carried out as in panel (A), except that the substrate corresponding to the first four lanes was a covalently closed circular MeG-T heteroduplex derived from pSYAH1A. The last 6 lanes correspond to a 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex. MutLα-supplemented reactions were done in duplicate. DNA was pre-treated with AGT as indicated.

DISCUSSION

Although subject to DNA alkylation damage by SN1 DNA methylators, cells deficient in MutSα or MutLα are resistant to the cytotoxic effects of such agents, including the clinically useful compounds temozolomide and procarbazine. Alkylation tolerance attributable to mismatch repair deficiency has been widely documented in cultured cell systems (2,4-6), but it is important to note that development of procarbazine resistance associated with MSH2 deficiency has also been demonstrated for a malignant glioma propagated as a xenograft in athymic mice (40). Attempts to account for the function of mismatch repair in the cytotoxic response to SN1 alkylating agents have invoked lesion recognition and perhaps processing by the system as key elements in the activation of the damage signaling kinases ATR and perhaps ATM (10,14-22,41).

To address involvement of the mismatch repair system in the processing of SN1 methylator lesions, we have examined the fate of heteroduplexes containing a single MeG-T mispair in nuclear extracts. Our findings demonstrate that this lesion activates the repair system irrespective of location of the MeG on the template strand or that subject to excision. When located on the template strand, MeG leads to abortive turnover of the other strand via mismatch-provoked excision and lesion bypass repair DNA synthesis, followed by a subsequent repair attempt, a process observed with both 5’ and 3’ MeG-T heteroduplexes. These results are consistent with the futile cycling model of Thilly and colleagues (10), which invokes turnover of newly synthesized DNA at the replication fork upon bypass of a template MeG and ultimate activation of damage signaling systems. While the work described here does not establish a link between iterative repair attempts and the activation of the damage signaling kinases, it seems unlikely that abortive turnover of newly synthesized DNA at the replication fork would go unnoticed by cellular damage sensing systems. On the other hand, only a small fraction of the MeG lesions resulting from SN1 methylator exposure are expected to be involved in a replication fork encounter at any given instant, and it has been suggested that MeG lesions residing in resting DNA may also trigger a damage response (22). However, these two mechanisms need not be mutually exclusive.

Model studies with bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase have implicated its 3’ to 5’ editing exonuclease in idling of the enzyme at template MeG lesions (42). While our results do not rule out a similar phenomenon involving a mammalian DNA polymerase, it is important to note that bypass of MeG lesions is an efficient process in nuclear extracts as judged by production of newly synthesized DNA segments that extend a hundred nucleotides or more beyond the location of a template MeG (Figs. 3A and 4A). Such segments are, however, subject to re-excision in a manner that depends on the integrity of the mismatch repair system.

We have also found that a very small but significant fraction of the irreparable 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex is subject to apparent incision on the nicked DNA strand at or near the thymidylate of the mispair, but the molecular events responsible for this MeG-dependent effect are not clear. Incision in this manner is reduced substantially with closed circular and irreparable 5’ MeG-T heteroduplexes, suggesting that such events may depend on heteroduplex orientation. While the initial round of abortive repair on a 5’-heteroduplex is expected to convert the molecule into a 3’-substrate, we have been unable to convincingly detect similar incision events with the 5’ MeG-T heteroduplex (not shown). Inasmuch as incision of the 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex is limited to 1-2% percent of the substrate (Fig. 5) and because re-excision is restricted to about 35% of the 5’ MeG-T molecules (Fig. 3), this detection problem could be due to a sensitivity issue. However, it could also reflect potential differences in the nature of repair complexes initially assembled onto 5’ and 3’ heteroduplexes. Furthermore, while the low-level incision observed with the 3’ MeG-T heteroduplex is MutLα-dependent, it is unclear whether this dependence on the mismatch repair system is direct or indirect. However, it is interesting to note in this regard that that previous studies have indicated physical and biological interactions between the mismatch repair system and other excision repair pathways (43,44), and that the human G-T mismatch thymine glycosylase is functional on MeG-T mispairs (45). Additional analysis of the nature of this phenomenon is underway.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was supported in part by grants R01 GM45190 and P01 CA92584 (to P.M.), and 1P50 CA108786 (to S.J.Y.). P.M. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. S.J.Y. was supported in part by a Physician Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute

References

- 1.Surtees JA, Argueso JL, Alani E. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;107:146–159. doi: 10.1159/000080593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojic L, Brun R, Jiricny J. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunkel TA, Erie DA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iyer RR, Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Modrich P. Chem Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li GM. Oncol Res. 1999;11:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karran P. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1931–1937. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. J Med Genet. 1999;36:801–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Chapelle A. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:769–780. doi: 10.1038/nrc1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowley PT. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:539–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.061704.135235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldmacher VS, Cuzick RA, Thilly WG. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12462–12471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karran P, Bignami M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2933–2940. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.12.2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel DJ, Shapiro L, Kozlowski SA, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1036–1042. doi: 10.1021/bi00353a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel DJ, Shapiro L, Kozlowski SA, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1027–1036. doi: 10.1021/bi00353a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duckett DR, Bronstein SM, Taya Y, Modrich P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12384–12388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stojic L, Mojas N, Cejka P, Di Pietro M, Ferrari S, Marra G, Jiricny J. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1331–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.294404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamson AW, Kim WJ, Shangary S, Baskaran R, Brown KD. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38222–38229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Qin J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536810100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caporali S, Falcinelli S, Starace G, Russo MT, Bonmassar E, Jiricny J, D’Atri S. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:478–491. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.3.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamane K, Taylor K, Kinsella TJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debiak M, Nikolova T, Kaina B. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duckett DR, Drummond JT, Murchie AIH, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lilley DMJ, Modrich P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6443–6447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kat A, Thilly WG, Fang WH, Longley MJ, Li GM, Modrich P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6424–6428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tominaga Y, Tsuzuki T, Shiraishi A, Kawate H, Sekiguchi M. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:889–896. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spratt TE, Levy DE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3354–3361. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.16.3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haracska L, Prakash S, Prakash L. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8001–8007. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8001-8007.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrino FW, Blans P, Harvey S, Gelhaus SL, McGrath C, Akman SA, Jenkins GS, LaCourse WR, Fishbein JC. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1616–1623. doi: 10.1021/tx034164f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L, Schwartz S, Davis BM, Gerson SL. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3070–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holmes J, Clark S, Modrich P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5837–5841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackwell LJ, Wang S, Modrich P. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33233–33240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genschel J, Bazemore LR, Modrich P. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13302–13311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Hays JB. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26136–26142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Hays JB. Mol Biotechnol. 2001;19:133–140. doi: 10.1385/MB:19:2:133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cejka P, Mojas N, Gillet L, Schar P, Jiricny J. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1395–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang W-h, Modrich P. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11838–11844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks P, Dohet C, Almouzni G, Mechali M, Radman M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4425–4429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas DC, Roberts JD, Kunkel TA. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3744–3751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drummond JT, Anthoney A, Brown R, Modrich P. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19645–19648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Genschel J, Modrich P. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1077–1086. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dzantiev L, Constantin N, Genschel J, Iyer RR, Burgers PM, Modrich P. Mol Cell. 2004;15:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedman HS, Johnson SP, Dong Q, Schold SC, Rasheed BK, Bigner SH, Ali-Osman F, Dolan E, Colvin OM, Houghton P, Germain G, Drummond JT, Keir S, Marcelli S, Bigner DD, Modrich P. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2933–2936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Branch P, Aquilina G, Bignami M, Karran P. Nature. 1993;362:652–654. doi: 10.1038/362652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khare V, Eckert KA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24286–24292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bertrand P, Tishkoff DX, Filosi N, Dasgupta R, Kolodner RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14278–14283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meira LB, Cheo DL, Reis AM, Claij N, Burns DK, Riele H, Friedberg EC. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:929–934. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sibghat U, Gallinari P, Xu YZ, Goodman MF, Bloom LB, Jiricny J, Day RSr. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12926–12932. doi: 10.1021/bi961022u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.