Abstract

PROBLEM ADDRESSED

The need for effective and accessible educational approaches by which family physicians can maintain practice competence in the face of an overwhelming amount of medical information.

OBJECTIVE OF PROGRAM

The practice-based small group (PBSG) learning program encourages practice changes through a process of small-group peer discussion—identifying practice gaps and reviewing clinical approaches in light of evidence.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The PBSG uses an interactive educational approach to continuing professional development. In small, self-formed groups within their local communities, family physicians discuss clinical topics using prepared modules that provide sample patient cases and accompanying information that distils the best evidence. Participants are guided by peer facilitators to reflect on the discussion and commit to appropriate practice changes.

CONCLUSION

The PBSG has evolved over the past 15 years in response to feedback from members and reflections of the developers. The success of the program is evidenced in effect on clinical practice, a large and increasing number of members, and the growth of interest internationally.

RÉSUMÉ

PROBLÈME À L’ÉTUDE

La nécessité de disposer de méthodes de formation accessibles et efficaces permettant au médecin de famille de demeurer compétent dans sa pratique face à la somme énorme d’information médicale.

OBJECTIF DU PROGRAMME

Le programme d’apprentissage en petit groupe en milieu de pratique (PGMP) facilite les changements de pratique par un processus de discussion en petits groupes de pairs, lequel permet d’identifier les façons d’agir déficientes et de revoir les méthodes cliniques à la lumière de données probantes.

DESCRIPTION DU PROGRAMME

Le programme PGMP a recours à une approche pédagogique interactive pour assurer le développement professionnel continu. Les médecins forment des petits groupes dans leur communauté locale où ils discutent de sujets cliniques à l’aide de modules tout faits qui fournissent des exemples de cas accompagnés d’information basée sur les meilleures données probantes. Des pairs aident les participants à réfléchir aux sujets discutés et à s’engager à apporter les changements appropriés à leur pratique.

CONCLUSION

Le programme PGMP s’est transformé au cours des dernières années en réponse à la rétroaction des participants et aux réflexions des responsables de son élaboration. Les changements des modes de pratique, le nombre de plus en plus grand de membres et l’intérêt croissant manifesté internationalement démontrent bien le succès du programme.

A major obstacle to the maintenance of practice competence is sheer volume new medical information, compounded by difficulties accessing relevant or “just-in-time” information.1 Indeed, research articles and clinical practice guidelines often “fail to adequately comprehend the complex nature of general practice,”2 which deals with illnesses and medical needs that are patient- and situation-specific.3 Family physicians learn better when practice-relevant evidence is synthesized.

Common continuing professional development (CPD) approaches (eg, lectures and handouts) to transmit new knowledge are ineffective in changing physician behaviour.4–6 Interactive approaches, however, can be effective, particularly when they involve participation in small peer groups that foster trust, promote discussion of evidence relevant to real cases, provide feedback on performance, and offer opportunities for practising newly learned skills.4, 7

Using sound educational principles, the practice-based small group (PBSG) learning program was developed to provide effective CPD with a practical, primary care focus to practising family physicians.8, 9 The PBSG learning program began in 1992 as a collaborative effort between McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, and the Ontario College of Family Physicians (OCFP), and has grown to a membership of more than 3500 physicians across Canada (Table 110).

Table 1.

Chronological development of PBSG

| YEAR | PBSG DEVELOPMENT |

|---|---|

| 1986–1987 | Feasibility study: pilot project with 8 family physicians discussing their practice cases in a group |

| 1992 | Ontario provincial pilot project with 16 small groups composed of 117 family physicians as a joint venture between McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, and the Ontario College of Family Physicians |

| 1994 | Program extended across Canada |

| 1995 | Accredited by the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) for Mainpro-C credits |

| 1997 | The Foundation for Medical Practice Education is established as a non-profit organization to administer the PBSG learning program based at McMaster University |

| 1997 and 2004 | Revision of facilitator training materials |

| 2004–2006 | The PBSG program forms international partnerships in Kenya, Scotland,10 and United States |

PBSG—practice-based small group.

One objective of the PBSG program is to encourage physician members to reflect on their individual practices and identify any gaps between current practice and the best available evidence. This is accomplished through discussion of real-life medical and patient problems in small groups of peers. Another objective is to encourage group members to initiate, as a result of this discussion, relevant changes to patient care. Within the group, members endeavour to identify specific barriers to these practice changes and to formulate implementation strategies to facilitate desired changes.

Program description

The PBSG learning program consists of 1) a group of family physicians willing to use a defined but flexible process to further their learning, 2) a facilitator who organizes the group, facilitates the learning process, and leads group discussion, 3) educational material in the form of modules, and 4) a tool that triggers reflection on new learning and its implementation into practice via a commitment to change.

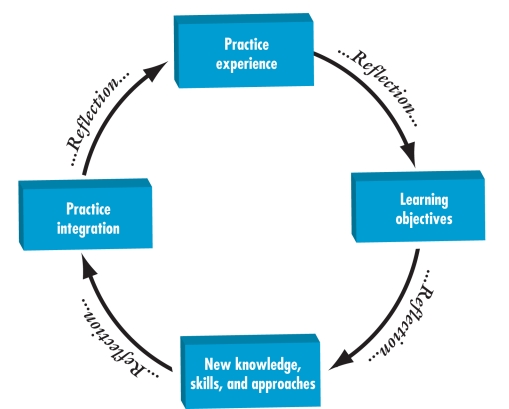

The theoretical basis for changing practice begins with the individual physician’s experience of patient care (Figure 1). Through reflection, a gap between current practice and best practice is recognized. Distinguishing this gap presents an opportunity to identify learning objectives specific to the family practice setting. The acquisition of new knowledge, skills, and approaches to bridge this gap follows. Often, however, access to new information alone is not sufficient. Reflection and discussion are necessary to help physicians 1) identify areas where current practice requires change and 2) develop strategies to integrate this new approach.

Figure 1.

Practice-based learning circle

The components of the learning program (group process, facilitator training, module development, and practice reflection) are intimately linked and interdependent. Each component is critical to the learning process and ultimately to practice change, with reflection being key.

Group process

Groups of 4 to 10 family physicians form a PBSG in their own communities, meeting for an average of 90 minutes once or twice a month at an agreed upon time and place, allowing time off for holidays and summer vacations.

Each group chooses a topic of discussion from a list of available educational modules based on member interest or identified patient challenges. For each module, groups are encouraged to examine learning objectives relative to their own learning gaps. Group discussion allows for sharing of experiences and of thoughts about strategies for implementing practice changes and about overcoming anticipated barriers.

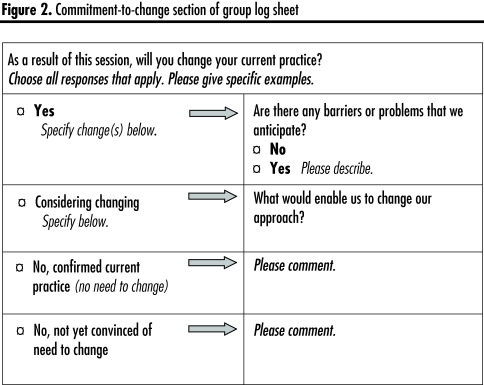

At the conclusion of each group meeting, a reflection tool is used to guide members in reviewing the discussion and explicitly committing to changing practice or reinforcing current practice. When there are great obstacles to change (eg, limited time, the need to acquire a new skill), the group might decide to set aside time to specifically address strategies for overcoming these barriers.

Facilitator role and training

A peer facilitator plays a vital role in the enduring success of each PBSG. The facilitator is selected by the group and trained in a 1.5-day workshop conducted by experienced facilitators. The workshop provides the new facilitator with individual opportunities to lead a small group using the PBSG modules, and with feedback around managing group process issues. The critical tasks of the facilitator are to focus discussion on real practice issues and to encourage the group to identify factors that assist or hinder implementation of new knowledge or skills into their individual practices. To successfully fulfill this role, facilitators must establish a safe, supportive environment that enhances the identification of practice gaps and encourages the discussion of sensitive patient care issues (including medical errors or ethical issues).

Modules

According to a letter from J. Wakefield, MD, CCFP, FCFP, in September 2005, PBSG modules are designed to engage family physicians “in learning activities that are self-directed and related to authentic practice problems.... The modules provide the practising physician with scientific data formatted into a practical educational framework.” The cases, linked with important information, are the keys to stimulating discussion around patient care issues.

Using a standardized format, family physicians produce 14 to 16 educational modules each year for other family physicians (Table 2). The topics are as diverse as hypertension, behavioural challenges of dementia, and patient safety.

Table 2.

Practice-based small group learning program module

| MODULE SECTIONS | DESCRIPTION OF SECTIONS |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | Identifies the practice gap and outlines the objectives for the module |

| 2. Authentic patient cases | Derived from actual practice cases, the cases are designed to highlight the practice gap |

| 3. Stimulus questions | Encourage physician reflection on an approach to the patient cases |

| 4. Information section | Best practice is outlined, including the specific levels of evidence for the recommendations |

| 5. Case commentaries | Provide one possible approach to the cases presented |

| 6. References | Materials supporting best evidence- based practices |

| 7. Appendices | Practical tools intended to facilitate physician change in practice: algorithms, chart aids, patient handouts, guides to resources, etc. |

Practice reflection tool

Accompanying each module is a log sheet—a structured tool for promoting reflection on the topic discussed at the group meeting and for identifying plans for practice change. The commitment-to-change section of the log sheet appears in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Commitment-to-change section of group log sheet

Lessons learned

Surveys for the PBSG learning program are regularly distributed to members and facilitators. The results have led to changes in all aspects of the program. Changes have also been triggered when the directors and staff have reflected on the program and when the relevant educational literature underpinning the program was reviewed.

Learning process in the group

Initially, problems with group functioning were anticipated, but they are surprisingly uncommon. Groups of various compositions function effectively in this particular small group environment. Homogenous (as to age, sex, and training) groups often develop an excellent supportive environment created by a shared understanding of the practice reality of the members; heterogeneous groups might provide broader practice experiences and greater variety in potential solutions to practice problems. Groups composed of people who practise together often have an advantage in determining common implementation strategies and ensuring appropriate follow-through.

Providing the modules before the meeting promotes reading and thinking about the content and adds to the richness of the group discussion.

Facilitator training

The more than 450 trained PBSG facilitators are the backbone of the program. If facilitators “burn out,” the group often dissolves. Training for facilitators has been expanded and revised. A standardized workshop has led to a more consistent application of educational principles within groups. Follow-up facilitator training is offered regularly to reinforce and enhance the facilitators’ practices, provide an opportunity to interact with other facilitators, and explore solutions to group issues.

Module development

The format and content of the modules have changed over time in response to member feedback. There are ongoing efforts to keep the modules focused, concise, and practical in order to most effectively accommodate the schedules of busy family physicians. To maintain consistent quality, the modules are rigorously scrutinized before being published Table 3).

Table 3.

Module development process (4–6 mo): Family physician authors have ongoing involvement in all phases of module development

| PROCESS |

|---|

|

Initially, the modules did not include cases, but physicians found it challenging to bring relevant “condensed cases” to meetings. Hence, practice cases were added to the modules to promote discussion around the identified gaps and to stimulate individual recall of similar patients. Open-ended questions were added to the cases to assist in exploring current approaches used by members. Case commentaries provide one possible approach to application of the new information.

Because physicians wanted to know the strength of the evidence presented, levels of evidence are now cited.

Time constraints of practising physician authors prompted us to develop a team of medical writers and experienced literature searchers to work with the family physician authors, which has greatly enhanced module development.

Reflection tool (log sheet)

The intention of the log sheet is to encourage practice reflection and capture practice change. Unfortunately, the tool is often viewed by groups as solely an administrative task for providing feedback to the program. Although periodic reviews are encouraged to determine whether or not changes in practice have occurred, some of the groups are not undertaking this task systematically.

Membership demographics

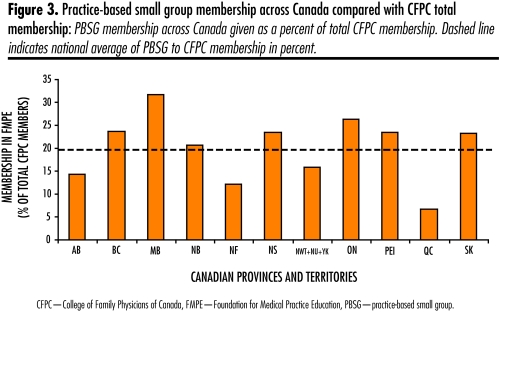

In 1992 PBSG began as an innovative program, a collaborative effort between McMaster University and the OCFP, with 117 physicians in 16 small groups across Ontario (Table 1). The program currently consists of more than 3500 members (Figure 3), comprising approximately 20% of the membership of the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC).

Figure 3.

Practice-based small group membership across Canada compared with CFPC total membership: PBSG membership across Canada given as a percent of total CFPC membership. Dashed line indicates national average of PBSG to CFPC membership in percent.

When the CFPC introduced Mainpro-C credits, the PBSG learning program was the first to be awarded these credits (Table 1). The removal of required Mainpro-C credits in 2003 caused a slight drop in PBSG membership, but in the subsequent 3 years, growth of membership numbers has resumed.

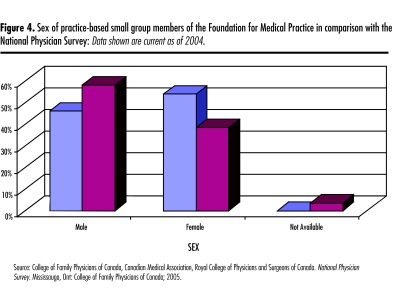

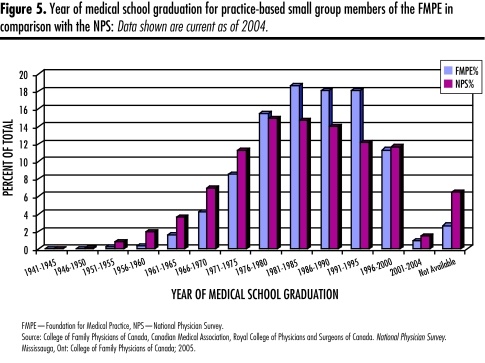

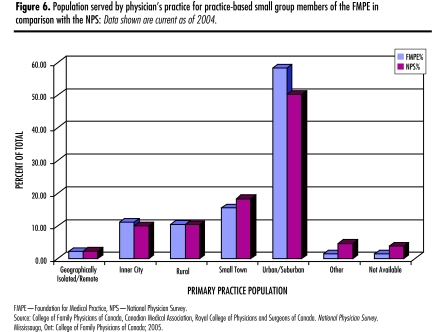

Compared with overall family physician data from the National Physician Survey (NPS), PBSG has a higher relative proportion of female participants to male participants (Figure 4). How year of medical school graduation among group members compares with that among NPS respondents is outlined in Figure 5. There are comparatively more members who graduated from 1981 to 2000. Finally, the location of practice of participants reflects that of the NPS database (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Sex of practice-based small group members of the Foundation for Medical Practice in comparison with the National Physician Survey: Data shown are current as of 2004.

Figure 5.

Year of medical school graduation for practice-based small group members of the FMPE in comparison with the NPS: Data shown are current as of 2004.

Figure 6.

Population served by physician’s practice for practice-based small group members of the FMPE in comparison with the NPS: Data shown are current as of 2004.

Within PBSG, nearly 80% have been members for 5 years or longer and nearly two thirds have been with the program for 7 or more years.

In member surveys, 90% of the respondents report the overall learning experience within the PBSG program to be good to excellent, with peer group interaction providing an enjoyable learning environment, an opportunity to share experiences, and a chance to focus on real practice issues.

Effect on practice

In a randomized controlled trial involving PBSG members (Better Prescribing Project11), change in prescribing practice was examined. Physicians who received feedback about personal prescribing or who used the PBSG process to discuss hypertension were more likely to change their prescribing than physicians in PBSG who reviewed a different condition. When feedback about personal prescribing was combined with the PBSG process, the effect on prescribing was even greater. Physicians who expressed a commitment to change on their log sheets were more likely, in the following 6 months, to change their actual prescribing for the target medications in 3 of 4 conditions.10

Despite viewing completion of the log sheet as an administrative task, more than 75% of the groups did so regularly. Of these log sheets, 83% described plans to make at least 1 specific practice change because of the module information and group discussion, and 90% reported making more general practice changes (eg, being more proactive in prevention and screening).

Discussion

Since 1992, the PBSG learning program has provided “opportunities for physicians to discuss the inherent difficulties involved in integrating new scientific discoveries into the realities of day-to-day clinical practice in a supportive and understanding culture.”8 The program has evolved over time, but the fundamental construct of the program remains interactive and reflective learning to facilitate changes in practice behaviour.

The demographics of program participation suggest that the program applies across physician practice locations. Physicians join slightly more in urban and suburban settings, possibly because it is relatively easier to find sufficient members in cities than in rural or remote locations. Although there is a slight difference in the proportion of women to men, this style of learning is applicable to and effective for both sexes. The increase in involvement by those who have trained since 1981 might reflect greater experience with small group learning in initial training.

The educational research literature addresses many components of the PBSG program. An interactive small group can prompt moderately large changes in physician practice.4–6, 9 Learning from and with colleagues is an important source of both new information and strategies for applying that information to practice.12–14 Exposure to the experiences and uncertainties of trusted colleagues could also enhance the accuracy of physicians’ self-assessment.15 Given the inaccuracy of physicians in assessing personal practice gaps, this collegial interaction can be pivotal16 in focusing the desire for competence that precipitates practice change.17

The use of a case-based format encourages activation of previous knowledge, allowing better retrieval of knowledge in the clinical setting.18 Elaboration of new knowledge is also facilitated through the “process of working with it, discussing it, and connecting it with what is already known.”19 Further, because physicians tend to generate at least 1 question for every 2 patients they see,20, 21 the opportunity to explore these questions in the groups can stimulate development of ideas for future change.17, 23

Implementation of new knowledge in the clinical setting is the ultimate goal of the small group meetings. In addition to the Better Prescribing Project,11 other studies have documented changes resulting from the learning in small peer groups.4, 23

Lack of strategies to assist implementation is an additional barrier to practice change.24, 25 Although a Cochrane review6 was unable to establish that identification and development of strategies address barriers, Ockene and Zapka26 were able to show a positive effect on practice change when change was encouraged and recognized. Encouraging and recognizing change is one of the crucial tasks of the PBSG facilitator. Further, the specific strategies identified within the group would be expected to enhance implementation. Focused printed materials, practice aids, and patient handouts can also facilitate practice implementation,27 and the modules often provide these.

A study by Pereles et al28 identified the important roles of the facilitator as promoting discussion and validation of practice, encouraging learning from each other, and developing a shared knowledge base and a sense of collegiality. However, if the facilitator lost interest or became fatigued, disintegration of the group was likely. The PBSG has developed both a follow-up meeting for experienced facilitators and an abbreviated workshop specifically for “replacement” facilitators. A benefit of these initiatives has been the opportunity to examine the educational processes occurring within existing groups and to provide direction and strategies to enhance learning.

Next steps

The Canadian membership in PBSGs has steadily increased, and now international interest is growing. Despite these successes, many aspects of the program require further exploration to ensure that constructive evolution continues. Identification of the gap between current practice and best practice is not always accurate, and strategies to enhance accuracy should be explored. Factors that contribute to an effective small group and the life cycle of a typical group have yet to be clarified. The critical contribution of facilitators has been discussed, but the elements contributing to the effectiveness and resilience of the facilitator need examination. Finally, further study of the factors that enhance subsequent practice implementation would clarify how physician practices change.

Conclusion

The current PBSG learning program has evolved steadily in response to feedback of members, reflection of developers, and review of the educational literature. Discussion focused on current practice issues and supported by evidence appears to provide accessible opportunities for practising physicians in small groups to enhance their implementation of new knowledge. Physicians trained in the past 25 years, of either sex, appear to be especially interested in this form of education.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the pivotal developmental role of Dr John Premi, Professor Emeritus at McMaster University. The program has benefited from the feedback and commitment of many members, authors, facilitators, and staff of The Foundation for Medical Practice Education (www.fmpe.org).

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The sheer volume of new medical information available can be overwhelming for family physicians.

Interactive approaches to learning, which include a synthesis of practice-relevant evidence, can be effective tools for busy family physicians in the maintenance of practice competence.

The practice-based small group learning program is an effective continuing professional development option for family physicians in Canada and beyond.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Par son seul volume, la nouvelle information médicale peut facilement submerger le médecin de famille.

Les méthodes interactives d’apprentissage qui comportent une synthèse des données pertinentes à la pratique peuvent être efficaces pour permettre au médecin de famille de maintenir un bon niveau de compétence.

Les programme d’apprentissage en petit groupes en milieu de pratique constituent un moyen efficace pour assurer une formation professionnelle continue aux médecins canadiens et d’ailleurs.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Hunt RE, Newman RG. Medical knowledge overload: a disturbing trend for physicians. Health Care Manage Rev. 1997;22(1):70–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlin Z, Humphrey C, Rogers S. General practitioners’ perceptions of effective health care. BMJ. 1999;318(7197):1532–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7197.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell C, Parboosingh J, Gondocz T, Babitskaya G, Pham BA. Study of the factors influencing the stimulus to learning recorded by physicians keeping a learning portfolio. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1999;19(1):16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282(9):867–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.9.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomson O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Oxman AD, Wolf F, Davis DA, Herrin J. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD003030. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Premi J, Shannon S, Hartwick K, Lamb S, Wakefield J, Williams J. Practice-based small-group CME. Acad Med. 1994;69(10):800–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Evidence for the effectiveness of CME. A review of 50 randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1992;268(9):1111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakefield J, Herbert CP, Maclure M, Dormuth C, Wright JM, Legare J, et al. Commitment to change statements can predict actual change in practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23(2):81–93. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbert CP, Wright JM, Maclure M, Wakefield J, Dormuth C, Brett-MacLean P, et al. Better Prescribing Project: a randomized controlled trial of the impact of case-based educational modules and personal prescribing feedback on prescribing for hypertension in primary care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(5):575–81. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haug JD. Physicians’ preferences for information sources: a meta-analytic study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997;85(3):223–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slotnick HB, Harris TR, Antonenko DR. Changes in learning-resource use across physicians’ learning episodes. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001;89(2):194–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhoeven AA, Boerma EJ, Meyboom-de Jong B. Use of information sources by family physicians: a literature survey. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1995;83(1):85–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van HR, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tracey JM, Arroll B, Richmond DE, Barham PM. The validity of general practitioners’ self assessment of knowledge: cross sectional study. BMJ. 1997;315(7120):1426–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox RD, Mazmanian PE, Putnam RW. A theory of change and learning. In: Fox RD, Mazmanian PE, Putnam RW, editors. Changing and learning in the lives of physicians. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers; 1989. pp. 161–77. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norman GR, Schmidt HG. The psychological basis of problem-based learning: a review of the evidence. Acad Med. 1992;67(9):557–65. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann KV. Thinking about learning: implications for principle-based professional education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22(2):69–76. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Covell DG, Uman GC, Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985;103(4):596–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorman PN, Helfand M. Information seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(2):113–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox RD, Miner C. Motivation and the facilitation of change, learning, and participation in the educational programs for health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1999;19(3):132–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veninga CC, Lagerlov P, Wahlstrom R, Muskova M, Denig P, Berkhof J, et al. Evaluating an educational intervention to improve the treatment of asthma in four European countries. Drug Education Project Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(4):1254–62. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9812136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazmanian PE, Daffron SR, Johnson RE, Davis DA, Kantrowitz MP. Information about barriers to planned change: a randomized controlled trial involving continuing medical education lectures and commitment to change. Acad Med. 1998;73(8):882–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199808000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw B, Cheater F, Baker R, Gillies C, Hearnshaw H, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD005470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ockene JK, Zapka JG. Provider education to promote implementation of clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2000;118(2 Suppl):33S–9S. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2_suppl.33s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazmanian PE, Davis DA. Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1057–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereles L, Lockyer J, Fidler H. Permanent small groups: group dynamics, learning, and change. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22(4):205–13. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]