Abstract

This longitudinal study followed 200 adolescents into early adulthood to explore the potential mediating roles that hostility, sadness, conduct problems, and risk taking play in the relationship between paternal alcoholism and substance abuse. Results indicated that paternal alcoholism predicted hostility; in turn, hostility predicted risk taking, which predicted substance abuse.

Negative affect may play an important mediating role in the relationship between parental alcoholism and offspring (COA) substance abuse. To date, most studies that have examined the relationship between negative affect and COA substance abuse have examined a general indicator of negative affect. However, recent research suggests that certain components of negative affect may be more strongly related to substance abuse than others [1]. Therefore, one goal of this study was to comparatively examine the potential mediating roles that hostility and sadness play in the relationship between parental alcoholism and substance abuse. Since theory (e.g., the deviance proneness model of vulnerability) [2] and research also suggest that conduct problems and risk taking may play intermediate roles in the relationship between parental alcoholism and COA substance abuse, another goal was to examine whether they further mediate this relationship.

Method

Participants

The participants were drawn from a larger longitudinal study (The RISK project) [3] that was designed to follow offspring of alcohol and drug dependent fathers over time. At Time 1, the sample included 200 15-19 year-old adolescents (68% Caucasian; 62% girls) and their biological fathers (56% alcohol dependent). The mean age of the adolescents was 16.76 (SD=1.35). All of the adolescents and their fathers were followed up five years later (Time 2).

Measures

The adolescents and their fathers were administered a psychiatric interview. The youth also completed questionnaires. Apart from the SSAGA, all of the measures were given only to the adolescents and were administered at Time 1, except for the substance abuse measures (which were given at Time 2). These measures consistently have been found to have good psychometric properties.

The Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA) [4] was administered to assess lifetime alcohol dependence, major depression, and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) in the fathers. Paternal depression and ASPD were included as covariates because they frequently are comorbid with alcohol dependence [5]. The adolescents completed the sadness and hostility scales from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [6] to assess negative affect, the 51-item Risk Taking Questionnaire [7] to measure adolescent risk taking, and the SSAGA to assess conduct problems (twenty items were summed to create a scale score). The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) [8] was used to measure youth substance abuse. Youth also were asked how often (in the past six months) they drank enough to get drunk or high. The response scale for these variables ranged from 1 = “never” to 8 = “nearly every day or more often.”

Procedures

The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Connecticut Health Center. Recruitment for the study took place through the community (e.g., YMCA/YWCA) and through alcohol/drug treatment programs and support groups. At both times of measurement, individuals who indicated that they were interested in participating were asked to call a research assistant for information and screening. If they were still interested after the phone call, they were invited to come to the university to provide informed consent and complete the measures previously discussed. All of the participants agreed to being contacted for a follow-up interview and additional testing five years after the initial testing. At Time 2, all participants were administered the SSAGA again. To compensate them for their time, the youth and their fathers each received a payment of $100 at Time 1 and $150 at Time 2. The attrition rate between Time 1 and Time 2 was 15%. Individuals who did not participate at Time 2 did not significantly differ from those who did participate at Time 2 on any of the demographic variables (e.g., gender, age) or substance use variables.

Results

Structural equation modeling was used to examine the underlying relations involved in the relationship between paternal alcoholism and substance abuse. In all models, paternal depression, paternal ASPD, and youth problem drinking (the Time 1 MAST score) were included as covariates. The first model tested a fully saturated model. This model did not fit the data well {X2(19)=291.86, p=.00; CFI=.88; RMSEA=.27). The second model was identical to the first model, with the exception that non-significant direct paths were deleted. The overall fit of this model was similar to the first model {X2(24)=297.11, p=.00; CFI=.88; RMSEA=.24}. In the third model, the non-significant specified paths from the previous model were deleted. This model also did not fit the data well {X2(35)=307.88, p=.00; CFI=.88; RMSEA=.20).

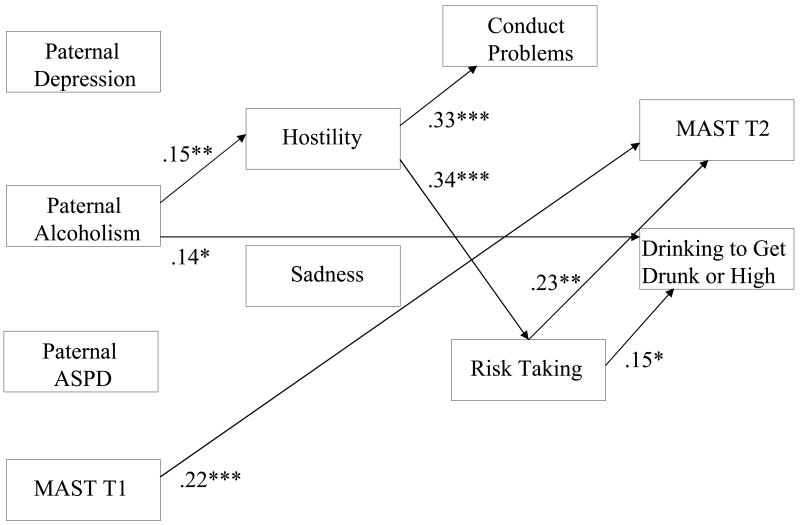

Examination of modification indices indicated that the disturbance terms between the endogenous variables should be allowed to be correlated. Therefore, a fourth model was conducted. In this model, the disturbance terms between the negative affect scales, conduct problems and risk taking, and the substance abuse indicators, were allowed to correlate with each other, respectively. The data fit this model well {X2(32)=74.35, p=.00; CFI=.98; RMSEA=.08). Of note, paternal depression and ASPD did not predict any of the endogenous variables. However, paternal alcoholism significantly predicted the frequency of drinking to get drunk or high (beta=.14, p<.05). As shown in Figure 1, significant indirect paths between paternal alcoholism and substance abuse also were observed. More specifically, paternal alcoholism significantly predicted youth hostility (beta=.15, p<.01); hostility subsequently predicted risk taking (beta=.34, p<.001); and risk taking, in turn, significantly predicted the MAST (beta=.23, p<.01) and frequency of drinking to get drunk or high (beta=.15, p<.05). Sobel tests confirmed that risk taking significantly mediated the relations between hostility and the MAST (c.r.=2.74, p<.01) and between hostility and frequency of drinking to get drunk or high (c.r.=1.97, p<.05). Of note, sadness was not involved in any of the indirect paths between paternal alcoholism and the substance abuse indicators.

Figure 1.

Note. For ease of interpretation, only significant standardized regression coefficients and their paths are shown.

Discussion

In this study, COAs had higher levels of hostility than non-COAs (see Table 1). In addition, consistent with the literature [9,10], hostility significantly predicted risk taking; which in turn, significantly predicted substance abuse. Importantly, this study extended the literature by simultaneously examining these indirect relations over time as adolescents transitioned into early adulthood, a critical period for the development of substance abuse problems.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables by COA Status

| COAs

|

Non-COAs

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Hostility * | 13.87 | 4.50 | 12.53 | 3.87 |

| Sadness | 11.10 | 3.96 | 11.05 | 4.29 |

| Conduct problems | 19.39 | 8.81 | 17.53 | 7.53 |

| Risk taking † | 14.84 | 8.85 | 12.33 | 8.33 |

| MAST * | 3.52 | 6.64 | 1.91 | 3.65 |

| Drinking to Get Drunk/High ** | 3.26 | 1.79 | 2.54 | 1.47 |

Note. n=200.

p<.10.

p<.05.

p<01.

p<.001.

In contrast to the results for hostility, sadness did not play a significant role. This finding conflicts with the literature, however, it should be noted that many depression measures include items relating to aspects of depression other than sadness (e.g., irritability). Therefore, it may be that sadness alone is not related to substance abuse.

Although the present investigation extends the current literature, caveats should be noted. As noted, the sample assessed was a high-risk sample. Caution should be used when generalizing the results to community samples. Mothers also did not participate in the study. Therefore, possible distinctions between paternal and maternal alcoholism could not be addressed.

Nonetheless, this study underscores the importance of longitudinally examining the underlying relations involved in the relationship between paternal alcoholism and youth substance abuse. Moreover, it highlight the importance of assessing distinct components of negative affect when examining the role that negative affect plays in the development of substance abuse problems.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the participants in the study. We also would like to acknowledge Cheryl McCarter for her unmatched dedication to the project. This research was supported by NIH grants 5P50-AA03510 and 1K01-AA015059.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Christine McCauley Ohannessian, Department of Individual & Family Studies, University of Delaware

Victor M. Hesselbrock, Department of Psychiatry, University of Connecticut Medical School

References

- 1.Swaim RC, Chen J, Deffenbacher JL, et al. Negative affect and alcohol use among non-Hispanic White and Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2001;11:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sher K. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houston RJ, Ceballos NA, Hesselbrock VM, Bauer LO. Borderline personality disorder features in adolescent girls: P300 evidence of altered brain maturation. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116:1424–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnburger JI, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesselbrock MN, Meyer RE, Keener JJ. Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:1050–1055. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340028004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief measure of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busen NH. Development of an adolescent risk-taking instrument. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1991;51(10B):4774–4775. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selzer M. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653–1658. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock V. Do personality and risk taking mediate the relationship between paternal substance dependence and adolescent substance use? Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussong AM, Hicks RE, Levy SA, et al. Specifying the relations between affect and heavy alcohol use among young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:449–461. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]