Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between scores on the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA), a performance-based measure of functional capacity, and level of patient community responsibilities (i.e., work for pay; volunteer work; attend school; household duties) in a Latino sample. Participants were 58 middle-aged and older Latinos of Mexican origin (mean age = 48.8 years) with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We conducted an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for age, symptoms of psychosis, and participant language, to determine if greater participation in community responsibilities was associated with higher functional capacity, as measured by the UPSA. Results indicated significant group differences in UPSA scores (F = 5.11, df = 2,51; p = .009), with patients reporting only a single community responsibility having significantly higher UPSA scores than those reporting zero community responsibilities (p = .016) and those reporting two responsibilities scoring significantly higher than those reporting zero community responsibility (p = .008). There were no differences found between those reporting one and those reporting two community responsibilities (p= .256). In contrast, no group differences were observed on the Dementia Rating Scale, a global measure of cognitive functioning (F = 2.14, df = 2,51; p = .128). These results provide initial support for the validity of the UPSA in Latino patients of Mexican origin, and suggest that improvement in functional capacity (i.e., UPSA scores) may be associated with increased capacity for greater community involvement in this population.

Keywords: UPSA, Hispanic, Culture, Functioning, Employment

1. Introduction

The Latino population is the largest and fastest growing minority ethnic group in the United States 1, 2. Parallel to this growth will be an increase in the number of Latinos with chronic psychosis, making it necessary for healthcare providers to increase access to effective services. However, data suggests there are disparities in the use of mental health services in the Latino population compared to non-Latino Whites 3, 4, perhaps due to barriers to initial service use (e.g., language capabilities, availability of services in one's community, and income level) 3, or to a reduced likelihood of continued service use due to Latinos' perception that the quality of care they received was poor or not relevant to their specific circumstances 5, 6. Therefore, to make healthcare services accessible and meaningful to Latino clients, healthcare providers need to address these barriers to quality care. One means of ensuring this is to provide valid assessments of patients in the language of their choice, and conduct assessments that produce relevant treatment recommendations and determine level of care required. Specifically, patients with psychosis and their families would greatly benefit from a valid assessment of the patient's ability to function in their communities 7.

Perhaps the most common method of evaluating patient ability to function in their communities is clinical evaluation. However, research suggests that clinical judgment ratings systems such as the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale tend to be poor predictors of living status and functioning 8, 9. Recent research suggests that persons with schizophrenia appear to have reduced capacity to perform everyday tasks necessary to function in their communities. Specifically, impaired cognitive functioning, which is common in individuals with schizophrenia, has been associated with worsened independent living skills in predominantly non-Latino samples 10, 11. However, Loewenstein and colleagues 12 warn that psychological tests of cognitive functioning may not adequately assess the constructs of interest for Spanish-speaking Latinos, and they argue that functional measures be used when assessing patient abilities to function in real-world settings 13.

The UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA) was recently developed to assess functional capacity in individuals with chronic psychosis and to determine patients' ability to carry out various tasks in real world situations. Data to date suggests that the UPSA is better at predicting one's current ability to function independently than measures of cognitive functioning 10, 14, 15. In a previous study, Mausbach and colleagues 14 reported that the UPSA was better than a measure of overall cognitive functioning in predicting current residential independence among persons with psychosis. However, this report, which did not examine the relationship between UPSA scores and level of community responsibility, may not be applicable to Latinos for several reasons. First, it included a primarily English-speaking non-Latino White sample. Second, predicting residential independence may be of reduced interest to Latinos because of the cultural value of “Familismo” or familism, whereby families strive to stay united especially in the face of adversity 16-18. This collectivistic family orientation is evidenced in Latino patients with schizophrenia who are more likely to be living with family 7, 19, 20 versus board and care or similar settings. Therefore, perhaps of greater interest to those in the Latino community is whether or not the person can perform tasks and take on responsibilities within their home or immediate community (e.g., contributing to daily chores, caring for other family members, working in the family business). In other words, the UPSA (as well as the outcome criterion of residential independence) may lack content validity in a Latino cultural context. However, if the UPSA could predict these traits, the test would be of strong interest and culturally relevant to these patients and their families.

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first to test the association between level of community responsibility and performance on the UPSA (i.e., concurrent validity) in a Latino sample. We hypothesized that among Latino participants, higher scores on the UPSA would be found among participants engaging in a greater number of community responsibilities (e.g., work for pay, volunteer work), even after accounting for variance related to age, symptoms, and language preference.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We recruited 58 middle-aged and older Latinos of Mexican origin with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. These participants had been enrolled in one of two research programs evaluating psychosocial interventions for improving functional skills. Half of the participants were enrolled in an English-only program known as Functional Adaptation Skills Training (FAST) 21, 22 and half in a Spanish-only program known as Programa de Entrenamiento para el Desarrollo de Aptitudes para Latinos (PEDAL)23. With the exception of language, the two studies had identical inclusion/exclusion criteria: a) a DSM-IV chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; b) no dementia diagnosis; c) no active suicidal ideation; d) ability to complete the assessment battery; e) no enrollment in any other psychosocial intervention or drug research at the time of intake, and f) symptoms are in “remission” (i.e., positive symptoms < 3 and negative symptoms < 4 and absence of delusions or hallucinations . Baseline assessments were used for the current study. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at University of California, San Diego (UCSD) approved the protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

2.2. Measures

Because this study consisted of both English and Spanish-speaking Latinos, measures that were not already professionally translated into Spanish were forward- and back-translated into Mexican Spanish using 3 professionals from 3 regions of Mexico. We provide citations below for those measures that have been previously translated and validated.

2.2.1. Functional Capacity

All participants completed the UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA) 24. This measure is designed to assess skills in five areas: a) Household Chores (e.g., cooking and shopping), b) Communication (e.g., using the telephone, rescheduling a medical appointment), c) Finance (e.g. counting change and paying bills), d) Transportation (e.g., using public transportation), and e) Planning Recreational Activities (e.g., organizing outings to the beach and the zoo). Total scores for each of the five subscales were calculated by converting raw scores into a 0-20 scale. A summary UPSA score was then calculated for each participant by adding these five scores, resulting in a total score from 0-100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Previous research has shown that the UPSA is related to everyday functional outcomes as rated by case managers 25.

2.2.2. Cognitive Functioning

To assess overall cognitive functioning, we administered Mattis' Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) 26, 27. The DRS consists of five subscales assessing participants' attention, initiation/perseveration, constructional abilities, conceptualization, and memory. Subscale scores are totaled to generate an overall score (maximum score = 144), with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning.

2.2.3. Community Responsibilities

We used the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) 28, 29 to assess participants' community responsibilities. The QOLI is a 44-item structured interview with four items assessing community engagement by asking participants the following “yes/no” questions: a) “During the past month, did you work at a job for pay?”; b) “During the past month, did you go to school?”; c) “During the past month, did you do volunteer work?”; and d) “During the past month, did you keep house or take care of children?” Number of Responsibilities was defined as the sum of positive responses (range=0-4).

2.2.4. Symptoms of Psychosis

Positive and negative symptoms of psychosis were assessed using the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) 30, 31. The PANSS is comprised of 30 items that assess three theoretical syndrome categories of psychopathology: Positive Symptom, Negative Symptom, and General Psychopathology Scales. The Positive Symptom Scale consists of seven items and rates severity of hallucinations, delusions, and inappropriate behavioral activity such as hostility, excitement and bizarre behavior. The Negative Symptom Scale has seven items that assess withdrawal and chronic inhibitory behavior. The General Psychopathology scale consists of 16 items regarding a variety of inappropriate or maladaptive behaviors. The PANSS is a 30 to 45 minute semi-structured interview administered by trained clinical interviewers.

2.3. Data Analysis

For each of our outcome variables (i.e., UPSA and DRS), we conducted an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to determine if greater participation in community responsibilities was associated with greater functional capacity. In our analyses, Number of Responsibilities was entered as the group variable, and a significant omnibus test was followed by LSD post-hoc tests. It is important to consider various confounds that can influence functional capacity in the Latino community. For example, Jeste and colleagues 32 previously found that acculturation was associated with functional capacity among Mexican-Americans with schizophrenia, whereby less acculturated Latinos had lower scores on the UPSA. These authors attribute these results to lower education and socioeconomic resources in the less-acculturated participants, and suggest that acculturation (and language preference) may serve as a proxy for these variables. Previous reports also indicate that older age and greater negative symptoms (but not general symptoms of psychosis) are related to worsened functional capacity 33-35 and therefore should be considered as covariates in any model assessing UPSA scores. As such, covariates for both the DRS and UPSA analyses included age, positive and negative symptoms, and English as a second language. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all analyses.

3. Results

Examination of our data indicated that the range of community responsibilities for our sample ranged from 0-2. We present the characteristics of the sample by number of community responsibilities in Table 1. Relative to other samples of middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia 22, 36, this sample was similar in terms of age (mean = 48.8 ± 8.2), years since diagnosis (mean = 22.8 ± 10.3), and levels of positive (mean = 15.8 ± 5.2) and negative symptoms of psychosis (mean = 15.4 ± 4.1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| 0 Responsibilities (n=22) |

1 Responsibility (n=29) |

2 Responsibilities (n=7) |

F | χ2 |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 47.7 (5.7) | 49.6 (9.8) | 48.7 (8.6) | 0.32 | .731 | |

| Range: 35-75 | ||||||

| Male, n (%) | 14 (64) | 15 (52) | 5 (71) | 1.27 | .530 | |

| Years of Education, M (SD) | 9.9 (2.8) | 9.7 (3.1) | 11.4 (3.6) | 0.96 | .389 | |

| Range: 4-17 | ||||||

| ESL, n (%) | 15 (68) | 18 (62) | 5 (71) | 0.33 | .848 | |

| Years since diagnosis, M (SD) | 21.3 (9.8) | 23.9 (10.6) | 23.0 (11.8) | 0.41 | .667 | |

| PANSS Positive, M (SD) | 15.1 (4.8) | 16.6 (5.3) | 14.7 (6.4) | 0.64 | .530 | |

| Range: 7-29 | ||||||

| PANSS Negative, M (SD) | 15.5 (4.1) | 15.9 (3.9) | 12.9 (4.4) | 1.61 | .209 | |

| Range: 8-24 | ||||||

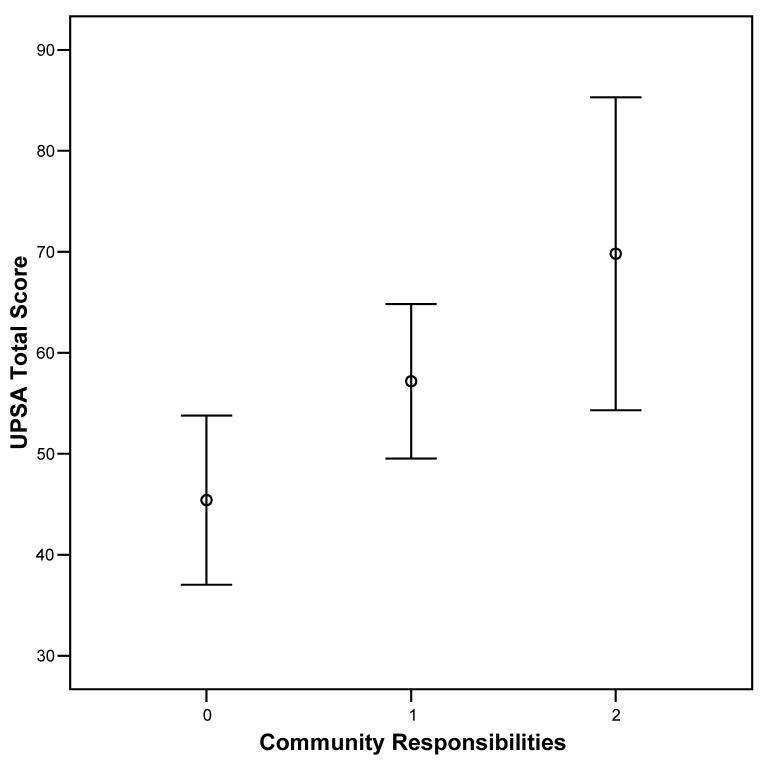

Our overall model explained 28.3% of the variance in UPSA scores. Figure 1 depicts mean (95% CI) UPSA scores by number of community responsibilities. After we controlled for age (coefficient = −0.49; F = 2.61, df = 1, 51, p = .112; ηp2 = .05), positive (coefficient = −0.39; F = 0.64, df = 1, 51, p = .428; ηp2 = .01) and negative (coefficient = −0.97; F = 2.32, df = 1, 51, p = .134; ηp2 = .04) symptoms, and English as a second language (coefficient = −7.77; F = 2.19, df = 1, 51, p = .145; ηp2 = .04), UPSA scores were significantly different between groups (F = 5.11, df = 2,51; p = .009; ηp2 = .17). In posthoc analyses, participants who reported only a single community responsibility had significantly higher UPSA scores (mean = 58.1, 95% CI = 51.1-65.1) than those reporting zero community responsibilities (mean = 44.9, 95% CI = 37.0-52.9) (p=.016). In addition, those reporting two responsibilities (mean = 67.4, 95% CI = 53.0 – 81.8) scored significantly higher than those reporting zero community responsibilities (p=.008). Finally, there was no significant difference between those reporting one and those reporting two community responsibilities (p = .256).

Figure 1.

Mean (95% CI) UPSA Scores by Number of Community Responsibilities

Mean (95% CI) DRS scores by number of community responsibilities are illustrated in Figure 2. Our model predicted 30.5% of variability in DRS scores. No significant group difference was found for DRS scores (F = 2.14, df = 2,51; p = .128; ηp2 = .08), and the only significant covariate was negative symptoms of psychosis (coefficient = −1.14; F = 9.87, df = 1, 51, p = .003; ηp2 = .16). Posthoc comparisons of those reporting one vs. zero responsibilities (p=.093) and those reporting two vs. zero responsibilities (p=.099) were not significant.

Figure 2.

Mean (95% CI) DRS Scores by Number of Community Responsibilities

We also computed Cohen's d 37 and Area Under the Curve (AUC) 38 effect sizes to indicate the magnitude of UPSA differences between the community responsibility groups. Briefly, Cohen's d expresses magnitude of differences in standard deviation units, with a value of 1 indicating that groups differ by 1 standard deviation. AUC represents the probability (%) that a randomly selected participant in one group would have a better result than a random participant in the comparison group. Our comparison of those with zero vs. one responsibility resulted in Cohen's d and AUC values of 0.70 and 68.7%, respectively. Our comparison of those with zero vs. two responsibilities yielded Cohen's d and AUC of 1.08 and 77.6%. Finally, our comparison of those with one vs. two responsibilities resulted in Cohen's d and AUC values of 0.39 and 61.0%.

We also conducted post-hoc analyses examining the correlation between illness chronicity (i.e., years since diagnosis) and engagement in community responsibility, in which the main and interactive effects of illness chronicity were entered as independent variables, and UPSA and DRS scores as dependent variables. Results of a Spearman correlation analysis indicated that years since diagnosis was not significantly correlated with number of community responsibilities (r = .12; p = .387). Furthermore, both the chronicity main effect (F = 0.13, p = .725) and the “chronicity × responsibility” interaction (F = 0.55, p = .580) were not significantly associated with UPSA scores. Similar results were observed for DRS scores. That is, chronicity (p = .271) and the “chronicity × responsibility” interaction (p = .931) were not significantly related to DRS scores.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the relationship between level of community responsibility and both measures of cognitive functioning and functional capacity among Latinos with schizophrenia. We found that individuals with greater community responsibilities demonstrated significantly greater performance on the UPSA, a performance based measure of functional capacity. However, greater community responsibility was not associated with significantly higher cognitive functioning as measured by the DRS. Although a direct comparison of the UPSA with the DRS was not made in this manuscript, these results appear consistent with those reported by Mausbach et al. 14. The current results therefore provide preliminary data indicating that the UPSA is sensitive to Latino patients' current level of community functioning as indicated by their engagement in various community responsibilities (e.g., work for pay).

Utilization of the UPSA carries several advantages. First, administration and scoring of the UPSA requires only 30 minutes, which makes it an effective tool for quickly evaluating a patient's capacity to engage in various community activities. Furthermore, unlike many measures of cognitive performance, administration of the UPSA does not require specialized training. These advantages make the UPSA appealing to healthcare professionals and agencies needing an efficient and time-sensitive assessment capable of capturing a patient's ability to function in the real world.

Providers may also use UPSA scores for treatment planning. For example, individuals with lower UPSA scores may be referred to appropriate skills training programs that emphasize tasks assessed by the UPSA. The extent to which these programs improve functional capacity may translate into increased capacity to engage in work or volunteer tasks. Indeed, Patterson and colleagues 23 tested the efficacy of a behavioral skills group intervention for Latinos, which taught a number of daily living skills including social skills, money management skills, and organizational skills over 24 weeks. Through modeling, in-class role-play exercises, and homework assignments, participants were given behavioral opportunities to observe and practice successful use of functional skills. Results indicated that this program successfully increased UPSA scores relative to a support condition, and these increases were sustained at 18-month post baseline. Although these investigators did not examine community-based service as an outcome, our current results suggest that this type of intervention may improve one's ability to engage in community activities. For example, as an individual scores higher on the UPSA, the patient may be encouraged to initiate new responsibilities that may further foster functional independence (e.g., volunteer work, school enrollment).

Of particular importance in the Latino community is the role of family members in patient care. For example, due to Latino cultural values of familismo/familism, immediate family members of Latino patients may be more likely to live with and provide informal care to their loved-ones 7, 19, 20. One area that family members may be involved is through making treatment decisions and determining patient activities, thereby relieving their own stress while empowering their loved ones. Caregivers may therefore desire input in determining if their loved ones are capable of taking on greater responsibilities (i.e., house chores, looking after other family members, running errands, or taking on a part-time job) that could serve to strengthen the family unit. We believe the UPSA could be used to inform family members of their loved-one's capacity to undertake new responsibilities and ultimately their progress through treatment. Further, providers could work with these family members to identify appropriate activities consistent with UPSA performance.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the data collected were from participants' baseline assessments, making this a cross-sectional evaluation of the concurrent validity of the UPSA. To examine predictive validity, a longitudinal design is required. Therefore, it is strongly recommended that a longitudinal analysis of the relations between UPSA scores and community responsibility be undertaken.

Patients' engagement in community responsibility was assessed by self-report rather than by informants or corroborating documents (e.g., pay stubs, school transcripts). Further, it is unclear how much time was spent by the participants in their stated activities (e.g., hours of work per week, volunteer time per week) or how well the activities were performed. Therefore, it is unclear the extent to which participants were truly engaged in their reported activities or the quality of work being produced. Future studies should address these limitations to ensure the validity of this measure. For example, we strongly encourage future researchers to assess quality of work performance and correlate these scores with UPSA scores.

Our sample consisted of 58 middle-aged and older Latino participants of Mexican origin, which may have limited power for finding relationships between variables in our model (e.g., negative symptoms and UPSA scores). Further, it is unclear how these results generalize to younger Latino participants or to other Latino groups. Certainly, there is much heterogeneity among Latinos in this country, including acculturation levels, language dialects, and regional influences. These differences can potentially affect not only UPSA scores but opportunities to engage in community responsibilities. Because of these limitations, future studies may wish to replicate these findings using larger samples comprised of various Latino subgroups of both younger and older participants. This will help investigators achieve greater power for finding associations between variables and to examine interethnic and intergenerational similarities and differences in the relationship between UPSA scores and community responsibilities.

Another limitation of the current study was our use of a brief cognitive assessment (i.e., DRS) that did not include several domains relevant to disability in schizophrenia. Specifically, future studies should include more comprehensive assessments of cognition, particularly working memory and processing speed, which have been associated with functional outcome in patients with schizophrenia 39.

Although participants were excluded if they scored very low on the PANSS (i.e., positive symptoms < 3 and negative symptoms < 4 and absence of delusions or hallucinations), a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder was established solely by chart review. Given the improved accuracy of combining chart review with structured clinical interviews 40, future researchers may wish to include a structured interview to establish the participants' diagnoses.

Overall, these findings are promising for demonstrating the potential usefulness of the UPSA for predicting real world functioning in Mexican origin Latinos with psychosis. Specifically, Latinos who engaged in more community responsibilities (e.g., work for pay, volunteer work) scored significantly higher on the UPSA compared with those with fewer responsibilities. These results may suggest that interventions for Latinos that successfully improve UPSA scores may ready them for greater involvement in their communities and potentially reduce the impact of the illness on their families and society. Yet more research within this community and among other Latino subgroups is strongly recommended.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported, in part, by awards 62554 (Patterson), 66248 (Jeste), 63139, and 19934 (Jeste) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and award 23989 (Mausbach) from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). We would like to thank Shah Golshan, Ph.D. and Lisa Eyler, Ph.D. for their advice in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.U.S. Bureau of the Census Race and Hispanic Origin: National Population Estimates by Age, Race and Hispanic Origin: 2003. http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/img/cb04-98-table1.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2007.

- 2.U.S. Bureau of the Census Projections of the Resident Population by Race, Hispanic Origin, and Nativity: Middle Series, 2006 to 2010. http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/005164.html. Accessed April 19, 2007.

- 3.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, Schlesinger HJ. Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(2):222–226. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguilar-Gaxiola SA, Zelezny L, Garcia B, Edmondson C, Alejo-Garcia C, Vega WA. Translating research into action: Reducing disparities in mental health care for Mexican Americans. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(12):1563–1568. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethical Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine; Washington, D.C.: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrio C, Yamada AM, Atuel H, et al. A tri-ethnic examination of symptom expression on the positive and negative syndrome scale in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;60:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revheim N, Medalia A. The independent living scales as a measure of functional outcome for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2004 Sep;55(9):1052–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Unutzer J, Ries R. Evidence for limited validity of the revised global assessment of functioning scale. Psychiatric Services. 1996 Aug;47(8):864–866. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.8.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functioning performance in Schizophrenia: Correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twamley EW, Doshi RR, Nayak GV, et al. Generalized cognitive impairments, ability to perform everyday tasks, and level of independence in community living situations of older patients with psychosis. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002 Dec;159(12):2013–2020. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewenstein DA, Arguelles T, Barker WW, Duara R. A comparative analysis of neuropsychological test performance of Spanish-speaking and English-speaking patients with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Gerongology. 1993;48(3):P142–149. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.p142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loewenstein DA, Rubert MP, Arguelles T, Duara R. Neuropsychological test performance and prediction of functional capacties among Spanish-speaking and English-speaking patients with dementia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 1995;10(2):75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mausbach BT, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, et al. Usefulness of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA) for Predicting Residential Independence in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.008. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer BW, Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, et al. Heterogeneity in functional status among older outpatients with schizophrenia: Employment history, living situation and driving. Schizophrenia Research. 2002 Jun;55(3):205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00218-3. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabogal F, Marïn G, Otero-Sabogal R. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galan FJ. Traditional values about family behavior: The case of the Chicano client. Social Thought. 1985;11(3):14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall GCN. Psychotherapy with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarnaccia PJ. Multicultural experiences of family caregiving: A study of African American, European American, and Hispanic American families. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 1998;77:63–73. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319987706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopelowicz A. Adapting social skills training for Latinos with schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry. 1998;10(1):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson TL, McKibbin C, Taylor M, et al. Functional adaptation skills training (FAST): A pilot psychosocial intervention study in middle-aged and older patients with chronic psychotic disorders. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003 Jan-Feb;11(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson TL, Mausbach BT, McKibbin C, Goldman S, Bucardo J, Jeste DV. Functional Adaptation Skills Training (FAST): A Randomized Trial of a Psychosocial Intervention for Middle-Aged and Older Patients with Chronic Psychotic Disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;86:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson TL, Bucardo J, McKibbin CL, et al. Development and Pilot Testing of a New Psychosocial Intervention for Older Latinos With Chronic Psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005 October 1;31(4):922–930. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi036. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment: Development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2001;27(2):235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinents of real-world functioning performance in Schizophrenia: Correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold BR, Cuellar I, Guzman N. Statistical and clinical evaluation of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale- Spanish adaptation: an initial investigation. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53(6):P364–P369. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.6.p364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehman AF. The well-being of chronic mental patients. Archives of general psychiatry. 1983 Apr;40(4):369–373. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790040023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehman AF, Postrado LT, Rachuba LT. Convergent validation of quality of life assessments for persons with severe mental illnesses. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 1993 Oct;2(5):327–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00449427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Vital-Herne M, Fuentes LS. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale: Spanish adaptation. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1990;178(8):510–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeste ND, Moore DJ, Goldman SR, et al. Predictors of everyday functioning among older Mexican Americans vs. Anglo-Americans with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1304–1311. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashworth JB, Reuben DB, Bention LA. Functional profiles of healthy older adults. Age and Ageing. 1994;23:34–39. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dawson D, Hendershot G, Fulton J. Aging in the eighties: Functional limitations of individuals age 65 and over. National Center for Health Statistics: Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005 Mar;162(3):520–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraemer HC, Morgan GA, Leech NL, Gliner JA, Vaske JJ, Harmon RJ. Measures of clinical significance. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003 Dec;42(12):1524–1529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26(1):119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basco MR, Bostic JQ, Davies D, et al. Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health settings. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1599–1605. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]