Introduction

There is a widespread belief that the symptoms of ‘hysteria’, as used to describe neurological symptoms such as paralysis or blackouts unexplained by disease, has become less common over the last 100 years.1-3 For example, in From Paralysis to Fatigue, his history of psychosomatic medicine, Edward Shorter argues that symptoms such as hysterical paralysis, which were common in the 19th century and famously demonstrated by Charcot, have now given way to more elusive symptoms such as fatigue.1 Common theories given for this ‘disappearance of hysteria’ include societal emancipation from repressive Victorian culture, increasing ‘psychological literacy’ in the 20th century and advances in understanding of neurological disease. Mark Micale, another historian of hysteria, also accepts the view that the more ‘florid’ types of hysteria are ‘regarded today as extreme rarities’.2

But as Jan van Gijn, Professor of Neurology in Utrecht, has recently commented, anyone who thinks that hysteria disappeared with the death of Charcot cannot know what goes on in neurology outpatient clinics.4 Ample data exists to show that conversion symptoms remain very common in neurological practice,5-8 a clinical reality that is curiously not reflected in research activity, teaching or public awareness.

It is puzzling, to say the least, that there should be such a discrepancy between medical historians and clinical neurologists. So what has happened? Did hysteria wane and is it now increasing again? Or has it always been common? In this essay we explore, using data where possible, some of the factors at work in this story. We conclude that there is no good evidence for a change in the frequency with which conversion symptoms (neurological ‘hysteria’) have presented to neurologists over the last 120 years. Instead, we propose that when the neurological study of disease and the psychiatric study of neurosis became divergent endeavours at the start of the 20th century, hysteria fell into a no-man's land between these two specialities. Neurologists were not interested in seeing the patients and the patients were mostly not interested in seeing psychiatrists. Scientific obliteration had become almost complete by the 1960s when flawed data was published which appeared to indicate that the diagnosis of hysteria usually turned out to be incorrect.9 We argue that it was not hysteria that disappeared, but rather medical interest in hysteria.

What is the evidence for a decline in the frequency of hysteria since the 19th century?

Edward Shorter, in his scholarly history of psychosomatic medicine From Paralysis to Fatigue,1 uses quotes from neurologists and psychiatrists to support his claim that ‘fits and paralyses that had been summoned from the symptom pool since the Middle Ages - spreading almost epidemically during the nineteenth century...virtually came to an end by the 1930s’. He provides good data to support the hypothesis that hysteria declined in psychiatric practice. But the evidence for a decline in hysteria in neurological practice is less compelling, coming from Israel Wechsler, a professor of neurology at Columbia in 1929, and from Schofield, a Harley Street doctor, in 1906.

What numerical data there are, although sparse, actually suggest that the rate of presentation of ‘hysteria’ in neurological practice has remained stable over time. In 1891 Guinon recorded ‘hysteria’ as the diagnosis in 8% of 3168 patients attending Charcot's outpatient clinic.10 Savill, at Paddington Infirmary and the West End hospital for Nervous Disease in 1909, recorded 500 patients with hysteria (including 28% with weakness).11 Contrasting this against Schofield's data from the same time indicates the importance of the setting when considering the incidence of a condition. Savill's breakdown of ‘hysterical’ symptoms was similar to that described by Briquet half a century earlier.12

During the First World War, ‘hysterical’ motor symptoms such as paralysis and movement disorders were attributed to a diagnosis of ‘shell shock’. The war renewed interest in hysteria, and proved beyond doubt something that had been observed for the previous few decades: that it was not just a condition of women. The scientific legacy of the First World War was predominantly to expand psychoanalytic interpretations of the symptoms; this remained the main flavour of the literature between the wars.

In 1955 Guillain in Paris compared his clinical practice to that reported by Charcot sixty years earlier.

‘In my recent outpatient consultations in the same hospital in the 20th century, I have the same number of sick patients but they are no longer given the name ‘hysteria’, but instead “Psycho-nervose” or “Troubles fonctionnels”. These illnesses have exactly the same symptoms as the illnesses which presented to Charcot. In reality, the illnesses have not changed since Charcot, it is the words we use to describe them that have changed.’10

Data from the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases, London, indicated a constant frequency of in patient admission for hysteria (1%) between 1951 and 1971.13 More recent studies of neurological inpatients in the UK, Germany and Denmark have reported proportions of neurology inpatients with ‘non-organic’ or ‘psychogenic’ disorder of between 7 and 9%.5,8,14

Perkin, a London neurologist, recorded in 1989 that 3.8% of 7836 neurology outpatient encounters had ‘conversion hysteria’.7 Additionally, studies in the UK, Holland and Denmark have consistently found that around one-third of neurology outpatients have symptoms ‘not at all’ or only ‘somewhat’ explained by disease.15-18

In conclusion, the case for ‘hysterical’ symptoms having disappeared between the late 19th century and modern times is not supported by the available data, although the lack of data from the middle of the century means that we cannot exclude the possibility that this represents a resurgence of cases rather than a persistence.

Neurological and psychiatric ideas separate and hysteria is orphaned

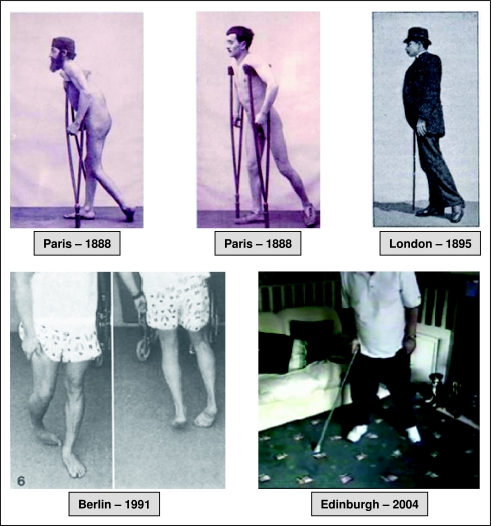

Where it is much easier to see a ‘rise and fall’ with respect to hysteria is in the degree of scientific interest it has generated. In the late 19th century, Charcot in Paris and Weir Mitchell in the USA were leaders in neurology and strongly interested in hysteria. In 1892, Freud and Breuer laid the foundations of psychoanalytic theory by talking to (and hypnotizing) patients with hysteria. But the frenzy over the topic gave way to disillusionment. Charcot's clinical observations of hysterical paralysis, numbness and contracture are still applicable to patients seen today (Figure 1). However, some types of hysteria that Charcot described at the Salpêtrière - for example the pseudo-epileptic ‘grand hysterie’ with its four phases - were rarely if ever observed in the UK, and interestingly also appeared to decline in Paris following his death.

Figure 1.

Historical consistency exists between clinical presentations of ‘hysterical’ symptoms from the time of Charcot to now. This montage shows consistency in the ‘dragging’ gait of functional paralysis. Paris 1888 from Charcot,25 London 1895 from Dercum,24 Berlin 1990 from Lempert et al. 26 (reprinted with permission from Springer Science and Business Media).

At the turn of the 20th century the psychological theories of Janet, Dubois and Freud were gaining ground on the one hand whilst there were huge and exciting opportunities for young neurologists to study the pathological basis of disease on the other. Where once there had been a single physician for ‘nervous diseases’, now there were two doctors - one of the brain, and the other of the mind. Neurologists had failed to find the pathological cause of hysteria and psychology was supplying some answers. It is hardly surprising, then, that Charcot's neurological descendants, inspired by his clinicopathological correlation, chose to concentrate on the hard end of neurological illness, leaving the ‘woolly’ subject of hysteria to the psychoanalysts.

Evidence for a decline in neurological interest in hysteria

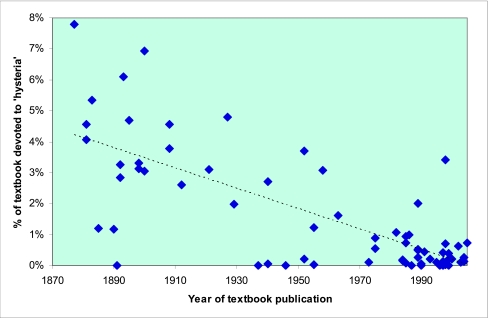

Evidence that interest in hysteria among neurologists has waned can be found in the content of general neurology textbooks published over the last 130 years. We systematically searched three medical libraries in Edinburgh, two in London (including the British Library) and one in Cambridge for English language textbooks covering the breadth of general neurology (excluding updated editions published less than 20 years apart). We counted the number of pages devoted to psychiatry; hysteria (all motor and sensory neurological symptoms not explained by disease or modern synonyms and ignoring psychiatric classification systems); clinical assessment of paralysis and seizure-like episodes not explained by disease (i.e. functional, non-organic or ‘hysterical’ or respective synonyms), analysing data from all four categories by year of publication to look for any trends over time using linear regression (www.statsdirect.com).

Sixty-eight textbooks of neurology were included in the review, with publication dates ranging from 1877 to 2005 (see supplementary references). Most textbooks were published in the UK (40) or USA (26). The proportion of neurology textbooks devoted to ‘hysteria’ was strongly negatively correlated with time (r=-0.74, P<0.0001) dropping from 3.7% (1877-1900) to 2.3% (1901-1950) and finally down to 0.5% in the last 50 years (1951-2005) (Figure 2). Similar drops could be seen with respect to the individual symptoms of functional paralysis (0.25 to 0.19 to 0.04% [r=-0.63, P<0.0001]) and non-epileptic attacks (0.72 to 0.20 to 0.07% [r=-0.45, P<0.001]). This decline was demonstrable despite a less consistent change in the proportion of the textbooks devoted to psychiatric subjects in general (6.1 to 8.1 to 2.3%).

Figure 2.

Proportion of general neurology textbooks devoted to ‘hysteria’ by year of publication (trend line indicates linear regression)

The presence of a specific chapter heading for ‘hysteria’ (or synonym) in 23 of the first 34 books in the study compared to nine in the latter 34 books may also indicate a change in neurological priorities over time. In most of the contemporary neurology textbooks, ‘non-organic’ problems featured only as something to rule out when looking for neurological disease, rather than a condition which needed independent description.

This bibliometric approach has limitations. First, our study probably only describes a fraction of all the textbooks of neurology that have been published since 1877, and only those in the English language. Second, there is an argument that ‘hysteria’ was used to describe a much broader range of clinical problems than it does now, (although the clinical descriptions in older textbooks are mostly highly comparable with those today). Finally, the reduced coverage of hysteria could be said simply to reflect the expansion of knowledge of other conditions and techniques in neurology. Despite these potential limitations we conclude that a clinical textbook is a reflection of the nature of the specialty it describes and the fact remains that the absolute amount of text on ‘hysteria’ in modern neurology textbooks is tiny, especially when set against the frequency of the problem.

One of the authors of this essay (CPW) is old enough to remember UK neurology attitudes to patients with conversion symptoms from the early 1970s. The main issue was simply that for most neurologists these were not regarded as a problem within the territory of neurology. Psychiatrists, then as now, often thought of them as rare. Young neurologists at that time learnt two things from their seniors: first, that their only role with these patients was to exclude neurological disease and discharge back to the general practitioner; and second, that many such patients were in any case ‘bogus’ or ‘faking it’.

Patients with hysteria not interested in seeing psychiatrists

But to understand the whole picture, it is not good enough to simply look at doctors' perceptions of hysteria as a clinical problem. To examine why psychiatrists in particular may believe that hysteria disappeared following the end of the 19th century, we must also look at the patient's perspective. How did patients with hysteria perceive things? When once they had one doctor, now they might have two: the brain doctors doing the diagnosis and the mind doctors taking care of the treatment. Since there is little indication what the illness beliefs of patients were 100 years ago we can only look at what patients with these symptoms think now. The major finding is that most patients with conversion symptoms consider that they have a neurological disease.19,20 This is not surprising given their physical neurological symptoms, the absence of public awareness, and the way that words such as psychosomatic are interpreted in the popular media (and by some doctors) as ‘faking it’.21

We don't know, but we suspect that patients with conversion symptoms have always tended to seek physicians and neurologists rather than psychiatrists. And a neurologist without interest in the problem may be less likely to refer onwards to psychiatry. This pattern of consulting may be important in understanding why psychiatrists, except those working alongside neurologists, rarely see patients with conversion symptoms and consequently why they might view it as an uncommon diagnosis.

Misdiagnosis drives another nail in the coffin

Going by the amount of published research, neurological interest in hysteria was already low by the time Eliot Slater published his highly influential study in 1965, which suggested a misdiagnosis rates of 60% or more.12 His conclusion, essentially that hysteria did not exist, came at a time when many of the excesses of psychosomatic theory would soon be proved wrong, for example explaining cervical dystonia as a ‘turning away of responsibility’. These factors did much to stifle research and interest in the area in the later 20th century.22 Recently, a systematic review of 27 similar studies since 1965 has found an average misdiagnosis rate of around 4% at five years of follow up, a rate similar to that found with other neurological and psychiatric diagnoses.23

Conclusion

The split between neurology and psychiatry, neurological disinterest in hysteria, physician anxiety over misdiagnosis, embarrassment at the excesses of psychological theory and the enthusiasm of patients with conversion symptoms to be told they have a neurological disease are all powerful reasons why hysteria has for so long been resided in a no-man's land between neurology and psychiatry. These factors may explain why it is often mistakenly believed that hysteria has declined in frequency since the time of Charcot. Now that we know the disappearance of hysteria is an illusion and not an historical mystery, perhaps the time has come to take much more than a historical interest in it?

DECLARATIONS

Competing Interests: None declared

Ethical Approval: Not Applicable

Funding and Sponsorship: Not Applicable

Guarantor: Dr Jon Stone

Contributorship: JS conceived the essay and bibliometric study. RH collected data. CW, AC and MS contributed to the manuscript

References

- 1.Shorter E. From paralysis to fatigue. New York: The Free Press, 1992

- 2.Micale MS. Approaching Hysteria. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994

- 3.Webster R. Why Freud was wrong. London: Harper Collins, 1996

- 4.van Gijn J. In defence of Charcot, Curie, and Wittmann. Lancet 2007;369: 462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lempert T, Dieterich M, Huppert D, Brandt T. Psychogenic disorders in neurology: frequency and clinical spectrum. Acta Neurol Scand 1990;82: 335-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parry AM, Murray B, Hart Y, Bass C. Audit of resource use in patients with non-organic disorders admitted to a UK neurology unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77: 1200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkin GD. An analysis of 7836 successive new outpatient referrals. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989;52: 447-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewald H, Rogne K, Ewald K, Fink P. Somatization in patients newly admitted to a neurological department. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994;89: 174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater ET. Diagnosis of ‘hysteria’. BMJ 1965;i: 1395-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillain G, Charcot J-M. 1825-1893. Sa vie - son œuvre. Paris: Masson, 1955

- 11.Savill TD. Lectures on hysteria and allied vasomotor conditions. London: Glaisher, 1909

- 12.Briquet P. Traité clinique et thérapeutique de l'Hysterie. Paris: J B Ballière, 1859

- 13.Trimble MR. Neuropsychiatry. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1981

- 14.Parry AM, Murray B, Hart Y, Bass C. Audit of resource use in patients with non-organic disorders admitted to a UK neurology unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77: 1200-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson AJ, Ringbauer B, Stone J, McKenzie L, Warlow C, Sharpe M. Do medically unexplained symptoms matter? A prospective cohort study of 300 new referrals to neurology outpatient clinics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68: 207-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. J Psychosom Res 2001;51: 361-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink P, Steen HM, Sondergaard L. Somatoform disorders among first-time referrals to a neurology service. Psychosomatics 2005;46: 540-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snijders TJ, de Leeuw FE, Klumpers UM, Kappelle LJ, van Gijn J. Prevalence and predictors of unexplained neurological symptoms in an academic neurology outpatient clinic - an observational study. J Neurol 2004;251: 66-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone J, Binzer M, Sharpe M. Illness beliefs and locus of control: a comparison of patients with pseudoseizures and epilepsy. J Psychosom Res 2004;57: 541-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binzer M, Eisemann M, Kullgren G. Illness behavior in the acute phase of motor disability in neurological disease and in conversion disorder: a comparative study. J Psychosom Res 1998;44: 657-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone J, Colyer M, Feltbower S, Carson A, Sharpe M. ‘Psychosomatic’: a systematic review of its meaning in newspaper articles. Psychosomatics 2004;45: 287-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stone J, Warlow C, Carson A, Sharpe M. Eliot Slater's myth of the non-existence of hysteria. J R Soc Med 2005;98: 547-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, Lewis S, Prescott R, Warlow C, et al. Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and ‘hysteria’. BMJ 2005;331: 989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dercum FX. A Textbook on Nervous Disorders by American Authors. Edinburgh and London: J Pentland, 1895

- 25.Charcot J-M. Nouvelle Iconographie de Salpêtrière. Clinique des maladies du systeme nerveux. Publiée sous la direction du par Paul Richer, Gilles de la Tourette, Albert Londe. Paris: Lecrosnier et Babé, 1888

- 26.Lempert T, Brandt T, Dieterich M, Huppert D. How to identify psychogenic disorders of stance and gait. A video study in 37 patients. J Neurol 1991;238: 140-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplementary references

- 1.Althaus J. Diseases of the Nervous System. London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1877

- 2.Hammond WA. A treatise on the disease of the nervous system. London: H.K.Lewis, 1881

- 3.McLane-Hamilton A. Nervous Diseases: their description and treatment (a manual for students and practitioners of medicine). London: J. & A. Churchill, 1881

- 4.Wilks S. Lectures on the Diseases of the Nervous System. London: J. & A. Churchill, 1883

- 5.Ross J. Handbook of the Diseases of the Nervous System. London: J. & A. Churchill, 1885

- 6.Suckling CW. On the Treatment of Diseases of the Nervous System. London: H.K. Lewis, 1890

- 7.Starr MA. Familiar Forms of Nervous Disease. New York: William Wood & Co, 1891

- 8.Ormerod JA. The Diseases of the Nervous System. London: J.& A.Churchill, 1892

- 9.Gowers WR. Diseases of the Nervous System. London: J.& A.Churchill, 1892

- 10.Hurt L, Hoch At. The Diseases of the Nervous System. London: Henry Kimpton, 1893

- 11.Dercum FX. A Textbook on Nervous Disorders by American Authors. Edinburgh and London: J. Pentland, 1895

- 12.Beevors CE. Diseases of the Nervous System: A Handbook for Students and Practitioners. London: H.K.Lewis, 1898

- 13.Dana CL. Textbook of Nervous Diseases. London: J.& A.Churchill, 1898

- 14.Collins J. The Treatment of Disease of the Nervous System - A Manual for Practitioners. New York: William Wood & Co, 1900

- 15.Oppenheim H, Mayer EE, translator. Diseases of the Nervous System: A textbook for student and practitioner of medicine. Philadelphia & London: J.B.Lippincott Co, 1900

- 16.Church A. Diseases of the Nervous System. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1908

- 17.Gorden A. Diseases of the Nervous System for General Practitioners and Students. London: H.K.Lewis, 1908

- 18.Bury JS. Diseases of the Nervous System. Manchester: The University Press, 1912

- 19.Thomson HC. Diseases of the Nervous System. London: Cassell & Co Ltd, 1921

- 20.Strecher EA, Meyers MK. Clinical Neurology for Practioners of Medicine and Medical Students. Philedelphia: P.Blakiston's & Co, 1927

- 21.Neustaedter M. Textbook of Clinical Neurology for Students and Practitioners. Philedelphia: F.A.Davis Co, 1929

- 22.Grinker RR. Neurology. London: Bailliere, Tindall & Cox, 1937

- 23.Wilson SAK. Neurology. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1940

- 24.Walshe FMR. Diseases of the Nervous System described for Practitioners and Students. Edinburgh: E.&S.Livingstone, 1940

- 25.Alpers BJ. Clinical Neurology. Philedelphia: F.A.Davis Company, 1946

- 26.Elliott FA, Hughes B, Turner JWA. Clinical Neurology. London: Cassell & Co, 1952

- 27.Purves-Stewart J, Worster-Drought C. Diagnosis of Nervous Diseases. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1952

- 28.Baker AB. Clinical Neurology. London: Cassell & Co, 1955

- 29.Brain R. Diseases of the Nervous System. London: Oxford University Press, 1955

- 30.Wechsler IS. A Textbook of Clinical Neurology. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders Co, 1958

- 31.Walshe FMR. Diseases of the Nervous System (Described for practitioners and Students). Edinburgh: E.&S.Livingstone, 1963

- 32.Merritt HH. A Textbook of Neurology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1973

- 33.Matthews WB. Practical Neurology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1975

- 34.Matthews WB, Miller H. Diseases of the Nervous System. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1975

- 35.Walton J. Essentials of Neurology. London: Pitman Med, 1982

- 36.Harrison MJG. Contemporary Neurology. London: Butterworths, 1984

- 37.Feldman RL. Neurology: The Physician's Guide. New York: Thiene-Stratton, 1984

- 38.Bannister R. Brain's Clinical Neurology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985

- 39.Ross-Russell RW, Wiles CM. Integrated Clinical Sciences: Neurology. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1985

- 40.Walton J. Brain's Diseases of the Nervous System. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985

- 41.Pryse-Philips W, Murray TJ. Essential Neurology. Norwalk, Connecticut: Appleton & Lange, 1986

- 42.Chadwick D, Cartlidge N, Bates D. Medical Neurology. London: Churchill Livingston, 1989

- 43.Bickerstaff ER. Neurology. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1987

- 44.Joynt RJ. Clinical Neurology. Philadelphia: J.B.Lippincott Co, 1989

- 45.Swash M, Schwartz MS. Neurology: A concise clinical text. London: Balliere Tindall, 1989

- 46.Marsden CD, Fowler TJ. Clinical Neurology. London: Edward Arnold, 1989

- 47.Gilroy J. Basic Neurology. New York: Pergamon Press, 1990

- 48.Gunderson CH. Essentials of Clinical Neurology. New York: Raven Press, 1990

- 49.Warlow CP. Handbook of Neurology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1991

- 50.Hopkins A. Clinical Neurology: A Modern Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993

- 51.Mohr JP, Gautier JC. Guide to Clinical Neurology. London: Churchill Livingston, 1995

- 52.Brandt T, Caplan L, Dichgans J, Diener H-C, Kennard C. Neurological Disorders: Course and Treatment. San Diego: Academic Press, 1996

- 53.Donaghy M. Neurology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997

- 54.Collins RC. Neurology. Philadelphia: W.B.Saunders, 1997

- 55.Adams RD, Victor M, Ropper AH. Principles of Neurology. Blacklick, Ohio: The McGraw-Hill Companies, 1997

- 56.Ellis SJ. Clinical Neurology: Essential Concepts. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998

- 57.Bogousslavsky J, Fisher M. Textbook of Neurology. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann, 1998

- 58.Rosenberg RN, Pleasure DE. Comprehensive Neurology. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1998

- 59.Weiner HL, Levitt LP, Rae-Grant A. Neurology. Philadelphia: Lipincott, Williams and Wilkins, 1999

- 60.Ginsberg L. Lecture Notes on Neurology. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2006

- 61.Wilkinson I. Essentials of Neurology. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1999

- 62.Gelb DJ. Introduction to Clinical Neurology. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann, 2000

- 63.Perkin GD. Mosby's Color Atlas and Text of Neurology. London: Mosby, 2002

- 64.Saunders MA, Feske SK. Office Practice of Neurology. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2003

- 65.Goetz CG. Textbook of Clinical Neurology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2003

- 66.Mumenthaler M, Mattle H. Neurology. Stuttgart: Thieme Verlag, 2004

- 67.Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J. Neurology in Clinical Practice. Philadelphia: Butterworth Heinemann/Elsevier, 2004

- 68.Corey-Bloom J. Adult Neurology. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005