Abstract

Previous work has suggested that “calcospherulites” actively participate in the mineralization of developing and healing bone. This study sought to directly test this hypothesis by developing a method to isolate calcospherulites and analyzing their capacity to seed mineralization of fibrillar collagen. The periosteal surface of juvenile rat tibial diaphysis was enriched in spherulites of ~0.5-micron diameter exhibiting a Ca/P ratio of 1.3. Their identity as calcospherulites was confirmed by their uptake of calcein at the tibial mineralization front 24 h following in vivo injection. Periosteum was dissected and unmineralized osteoid removed by collagenase in order to expose calcospherulites. Calcein-labeled calcospherulites were then released from the mineralization front by dispase digestion and isolated via fluorescence flow sorting. X-ray diffraction analysis revealed they contained apatite crystals (c-axis length of 17.5 ± 0.2 nm), though their Ca/P ratio of 1.3 is lower than that of hydroxyapatite. Much of their non-mineral phosphorous content was removed by ice-cold ethanol, elevating their Ca/P ratio to 1.6, suggesting the presence of phospholipids. Western blot analyses showed the presence of bone matrix proteins and type I collagen in these preparations. Incubating isolated calcospherulites in collagen hydrogels demonstrated that they could seed a mineralization reaction on type I collagen fibers in vitro. Ultrastructural analyses revealed crystals on the collagen fibers that were distributed rather uniformly along the fiber lengths. Furthermore, crystals were observed at distances well away from the observed calcospherulites. Our results directly support an active role for calcospherulites in inducing the mineralization of type I collagen fibers at the mineralization front of bone.

Keywords: bone formation, mineralization front, calcospherulites, biomineralization, bone matrix proteins, type I collagen

Introduction

During juvenile growth periods, the tibia exhibits both endochondral and intramembanous bone formation processes. Endochondral bone formation occurs at the epiphyseal growth plates of the tibia in order to lengthen this long bone. An intramembranous bone formation process occurs along the bone shaft, or diaphysis, which rapidly widens the girth of the cortex primarily by a robust bone formation response at the periosteal surface [1]. The molecular mechanisms promoting the nucleation and propagation of mineral phases within the extracellular matrix of bone is an overall process referred to as biomineralization. Calcification of growth plate cartilage starts with the release of unilamellar vesicles having an average outer diameter of 100-nm from the cell membranes of late-hypertrophic chondrocytes into the extracellular matrix space [2–4]. An initial nucleation reaction associated with the vesicle membranes is followed by an extrusion of crystals out of the vesicles and into the extracellular space, often leading to an aggregation/growth of crystals into larger-sized structures [5]. It is thought that this mechanism leads to a uniform, evenly distributed, mineral phase throughout the calcifying cartilage matrix, which then acts as a mineralized scaffold onto which osteoblasts migrate to form bone tissue [2–4].

Matrix vesicles have also been detected in several bone tissue types from embryonic to adult ages exhibiting either normal or pathological physiology [reviewed in 6]. In contention at the moment is not their presence in osteogenic tissues and osteiod, but rather their prevalence particularly in dense cortical bone [7]. Boyde and Sela [8] described a temporal transition of matrix vesicles forming larger, mineralized structures referred to as “calcopherites” or “calcospherulites” at the mineralization front of bone. In this scenario, matrix vesicles were thought to aggregate into calcified particles that eventually fuse with and seed the calcification of the collagen fibers at the mineralization front [8,9]. It has also been suggested that these structures may represent simultaneous, parallel reactions that exhibit some purposeful or coincidental interaction [4,7]. Relevant to the present study, matrix vesicles and calcospherulites have been observed at the periosteal surface of tibial diaphyses in young rats, and some calcospherulites were reported to be in close contact with the collagen fibers at the mineralization front [10].

Many other investigators have reported the presence of calcified, spherical-shaped structures along the mineralization front of bone [11–19]. Recently, we have reported that calcified spherulites tend to cluster in select matrix areas during periods of rapid bone formation, and that this focal process is defined by an extracellular matrix assembly of bone acidic glycoprotein-75 (BAG-75)1 referred to as biomineralization foci (BMF) [20,21]. One of the bone matrix proteins associated with these spherulites, bone sialoprotein (BSP) [13,16], has been shown to nucleate apatite crystals in vitro [22]. It is not known how these spherulites form or how they interact with fibrillar collagen, which stems, in part, from a lack of a method to release and recover these structures specifically from the mineralization front of bone [17].

The current study’s objective was to develop a means to isolate calcospherulites from the mineralization front of bone. These isolated calcospherulites would then be used to test the hypothesis that isolated calcospherulites can seed the mineralization of collagen fibers. Direct in vivo labeling of the initial mineral phase at the mineralization front of tibial diaphyses was achieved by injection of a low dose of calcein into living 30-day old rats. This approach provided an unambiguous means to establish the identity of newly formed bone mineral, and provided a reporter chemistry, which permitted the detection and isolation of labeled calcospherulites. X-ray diffraction and elemental analyses provided a quality assurance that the mineral phase of calcospherulites was recoverable during isolation. Finally, to validate our hypothesis, isolated calcospherulites were incubated in collagen hydrogels in vitro, and they were observed to seed a mineralization reaction on type I collagen fibers.

Materials and methods

Materials

All reagents used in this study were of the highest purity commercially available. Antibodies used in this study were AF808 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for detection of osteopontin, anti-rat collagen type I (Chemicon International, AB755P), anti-BAG-75 (#504; Dr. Jeff Gorski, Univeristy of Missouri-Kansas City), and LF-87 (gift kindly supplied by Dr. Larry Fisher, NIDCR, NIH) for detection of bone sialoprotein [23].

Tissue Isolation

All animal procedures used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Weanling male rats (~45 g body weight) were injected in vivo using a single intraperitoneal delivery of 10-μg/g body weight of calcein in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. Rats were allowed free cage activity for a 24 h period after calcein injection prior to euthanasia by asphyxiation with CO2. In some rats, the calcein injection was followed up 3 days later with a second injection of alizarin red-S (10-μg/g BW). These rats were allowed free cage activity overnight prior to euthanasia. A 7 mm-long segment from the middle diaphysis of each tibia was obtained from the rats using aseptic techniques. Periosteal tissue layers, including most of the basal cambium cell layer, were stripped off the bone by dissection as previously described [24].

Undecalcified Tissue Sectioning

Specimens were fixed in 70% ethanol buffered to pH 7.5 with 10 mM HEPES for 16 h at 4° C. The samples were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and embedded in methyl methacrylate plastic after serial dehydration with a graded ethanol series to xylene. Sections of 7-μm thickness were cut and placed on Superfrost slides. De-plasticized bone tissue sections were stained for 24 hours in freshly prepared 0.01% Toluidine blue, pH 8.0. Staining was followed by a brief distilled water rinse, and specimens were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Sections were then cleared in xylene and mounted with Permount.

Brightfield Microscopy of Calcospherulites

Images of toluidine blue stained sections were acquired in color using a Leica RXA2 upright wide-field microscope (Heidelberg, Germany), Spot RT CCD digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and 40X, 63X, and 100X objectives. Concurrently, stained sections were imaged in grayscale using a Leica TCS AOBS SP2, laser scanning confocal microscope in transmission mode with a 63X oil immersion objective (N.A.=1.4) and an optical zoom capacity of an additional 4X (total magnification of 252X). The coherent 488 nm (Argon) laser line utilized for acquisition provided the necessary clarity and resolution for zooms up to 4 times the objective magnification. Since calcospherulites were present at multiple focal planes, 1024 × 1024 pixel slices were acquired at regular 0.25 μm intervals for each field of view. Line averaging (8X) was performed at each focal plane to eliminate noise. Acquired slices were subsequently imported into Image-Pro Plus (v.5.1 Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD) as individual image stacks. Following normalization of light intensity throughout each stack, a “best focus” image was generated using maximum local contrast criterion.

Calcein-labeled Calcospherulite Imaging

Images of 7 μm thick tissue sections labeled with calcein were acquired using a Leica TCS AOBS SP2, laser scanning confocal microscope (Heidelberg, Germany), a 63X oil immersion objective (N.A.=1.4), 488 nm Argon laser excitation, and 500–550 nm emission. As discussed above, 1024×1024 pixel slices were acquired to ensure that all calcospherulites were imaged in each field-of-view. In order to minimize photo bleaching, slices were spaced at 0.5 μm intervals using 4X line averaging. Subsequently, slices acquired for each field of view were used to generate a maximum intensity projection image from within Leica’s acquisition software.

Morphometric Analysis of Calcospherulites

Confocal slices of toluidne blue- or calcein-labeled calcospherulites (~10–15 slices/field of view) were imported into Volocity 3.6 (Improvision, Lexington, MA). Using a point-spread function based on the objective aperture and excitation wavelength, slices were deconvolved and then reconstructed into 3-D volumes. Prior to analysis of spherulite dimensions, regions of interest at the mineralization front were defined within each volume, segmented (100–255 gray levels) to isolate spherulites, and processed using watershed filters to split apart connected spherulites. Finally, skeletonized diameters of segmented spherulites for each volume were exported to text files.

Enzyme digestions

Following dissection, and only at this time, each bone cylinder was plugged at both open ends using bone wax (Fine Science Tools, Inc.). This was done to assure access of enzymes and reagents to the periosteal bone surface only, and did not interfere with enzymatic digestions nor contributed extractable proteins that might interfere with Western blot analyses. The osteoid matrix on the periosteal surface of the wax-plugged bone cylinders was isolated using type I collagenase (Boehringer Mannheim) digestion (0.5 mg/ml) in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution plus the serine protease inhibitor 4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzene sulfonyl fluoride at 1 mM for 16 h at 37° C. Subsequent dispase digestions were done using 6 U/ml dispase (Boehringer Mannheim) for 30 minutes at 37° C in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.6) with end over end nutation.

Electron Microscopy Imaging

Following the dissection of periosteal tissue, some tibia diaphyses were dehydrated directly with a graded acetone series (70% for 15 minutes, 90% for 15 minutes and finally at 100% for 15 minutes twice). Other specimens were digested with type I collagenase prior to dehydration to remove non-mineralized osteoid, while other specimens were digested first with collagenase and then with dispase to isolate the mineralization front matrix. After dehydration, all specimens were then coated with palladium and examined with a Hitachi-S4500 FEG SEM. The accelerating voltage was 5 kV for imaging and 10 kV for energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis.

Following collagenase and dispase digestions to release calcein-labeled spherulites (mineralization front matrix), the samples were submitted to low-speed centrifugation (100g for 5 minutes to remove any large aggregates and partially digested matrix), and then to high-speed centrifugation (30,000g for 20 minutes). The high-speed pellets were resuspended with water at pH 8.0. A drop of the solution was spotted onto a formvar-coated, carbon-reinforced copper grid for TEM evaluation in a Philips CM 20 TEM operating at 100 kV. A liquid nitrogen cooling stage was used to minimize contamination. Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was used to study the elemental composition of isolated particles.

Fluorescence Flow Sorting

Following collagenase (osteoid matrix) or collagenase-dispase (mineralization front matrix) digestion to release calcein-labeled spherulites, the samples were submitted to low-speed centrifugation (100g for 5 minutes), and then to high-speed centrifugation (30,000g for 20 minutes). The high-speed pellet was resuspended with a solution of 1% bovine serum albumin (Fraction V, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS, and then transferred to analysis tubes (Falcon 352058). Recovered spherulites were then analyzed by FACS analysis using a 488 nm excitation line from an argon laser (Becton Dickinson FACScan, San Jose, Ca). The sorter was gated to count particles smaller than 3 microns using PolybeadR Dyed Yellow 3.0 micro-spheres (#17139, Polyscience Inc., Warrington, PA). Data was analyzed in histogram mode using FlowJo software, V6.1.1 (Tree Star Inc.).

X-Ray Diffraction

Dispase-released calcospherulites from 24 tibial diaphyses were isolated by flow sorting and pelleted by centrifugation (30,000g for 20 minutes). The pellets were washed three times with 70% ethanol and lyophilized prior to analysis (~5 mg dry weight). All sample data were compared to a reference standard of a well-crystallized hydroxyapatite as previously described [25]. Diffraction patterns were recorded with a Rigaku X-Ray Diffractometer equipped with a graphite monochromator calibrated to CuKα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) and with a scintillation counter detector coupled to a linear ratemeter for data collection. This analysis utilized a continuous scan between 23 and 37° 2θ (where 2θ = the scattering angle) at an angular velocity of 0.25° 2θ/minute. The modulated (10 sec) time constant analog output signal from the ratemeter was converted at 0.01° intervals for plotting. The (002) apatite standard peak (between 24.7 and 27° 2θ) was recorded a minimum of four times at an angular velocity of 0.125° 2θ for X-Ray Line Broading analysis.

Protein Extractions

Other high speed pellets were resuspended in a strong denaturant and chelation solution containing protease inhibitors (4 M guanidine HCl, 0.4 M EDTA, 2% Triton X-100, 100 mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM benzamidine HCl, 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.8) with mixing for 24 h at 4° C. Recovered extraction solutions (0.5 ml volume) were desalted on Sephadex G-50 columns (7 mm × 80 mm) eluted with 10 M formamide, 1% CHAPS, 150 mM NaCl, and 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.8. Void volume samples were concentrated on Microcon YM-3 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) and then mixed with an equal volume of 2X SDS sample buffer. Protein content was measured by Pierce Micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL).

Western Blot Analysis

Two μg of concentrated protein from each sample was applied in a total of 12 μl volume to each lane in SDS-polyacrylamide linear 4–20% gradient minigels using the Laemmli buffer system (1 mm width, 12 well, Invitrogen, EC60252). Gels were run at 125 volts for 2 hours. Some gels were stained with Molecular Probes Sypro Tangerine Orange Protein Gel Stain (Eugene, OR, S-12010) to view protein-banding patterns, while other gels were transferred to Millipore Immobilon-P membranes (IPVH10100) in a wet-blot module at 30 volts for 5 hours. Western blot analysis was performed following blocking over night in 5% ovalbumin in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Primary (1:1000 dilution) and secondary (1:15,000 dilution) antibodies were diluted into 0.1% ovalbumin in TBS, and exposed to the blot membrane for overnight at 4° C and 2 h at room temperature, respectively. Positive signals were detected using ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare BioSciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

Collagen Hydrogels

Four ml of rat tail collagen type I solutions (4.3 mg/ml) (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) were mixed with 0.5 ml of 10x Earl’s balanced salt solution containing 0.64% HCO3, and 0.12 ml of 1 M NaOH on ice. Ten-microliter aliquots of ice-cold collagen solution, with or without a 1-μl aliquot of calcospherulite suspension (4 μg/μl protein), were dropped onto 6-well culture plates and then incubated for 60 min at 37° C to form collagen hydrogels. Collagen hydrogels were incubated in 2 ml of Eagle’s modified essential medium (2 mM calcium and 2 mM phosphate) containing 0.5% BSA for 72 h. At this endpoint, the resulting collagen hydrogels were analyzed by thin-section, transmission electron microscopy to determine the ultrastructural morphology of the surrounding organic and inorganic matrix. Hydrogels were fixed for 12 h with 2.5% v/v glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. After rinsing in buffer and dehydration in a graded ethanol solution series, samples were embedded in Spurr’s plastic. After trimming, 80 nm thin sections were placed on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and examined in a JEOL 1200 EX II transmission electron microscope.

Results

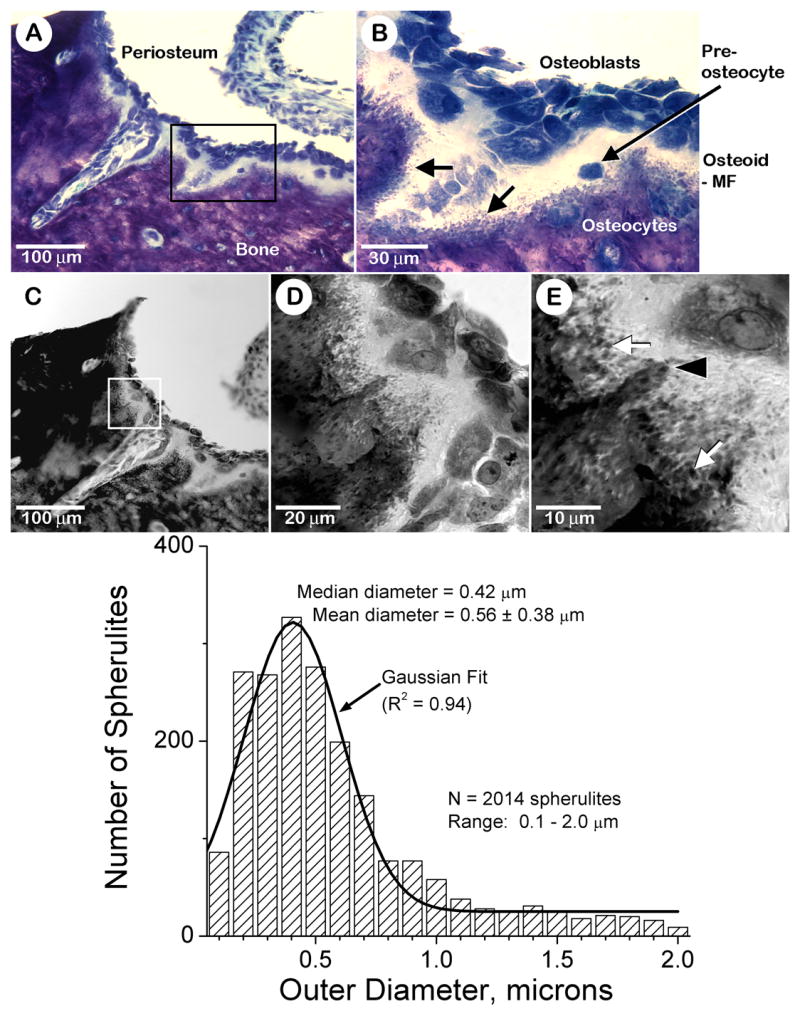

The Mineralization Front of Bone Contains Numerous Spherulites

The mineralization front of bone is readily apparent in undecalcified sections of juvenile rat tibial diaphysis stained with Toluidine blue (Fig. 1). The bone tissue side of this interface stains a dark purple color, while the unmineralized osteoid matrix side stains a light blue to rose color (Fig. 1A). Osteoblasts overlying the osteoid surface, and preosteocytes within the osteoid matrix, stain a deep blue color (Fig. 1B). At 100X magnification, the apical surface of the mineralization front appears as discrete small particles or “spherulites” (Fig. 1B; black arrows). These spherulites have a purplish-blue color appearance more resembling that of the underlying bone tissue and less like that of osteoid in these tissue sections. When viewed with transmission-mode, confocal microscopy at 250X, these dark spherulites were distributed all along the apical aspect of the mineralization front (Fig. 1C,D). It revealed a band of spherulites along the apical aspect of the mineralization front and the basal portion of the osteoid layer (Fig. 1E; white arrows). Morphometric analysis revealed they exhibit an average diameter of 0.56 ± 0.38 microns (Fig. 1 histogram). These dark spherulites were also noticed near and around the cell processes of newly embedded osteocytes projecting up into the osteoid layer (Fig. 1E; black arrowhead).

Fig. 1. The mineralization front of bone exhibits spherical particles (spherulites).

Panels A and B: Brightfield microscopy images of a toluidine blue-stained undecalcified section of tibial diaphysis tissue from a juvenile male rat. Periosteum and bone tissue locations are noted (panel A). The box in panel A identifies a region of interest at the mineralization front that is shown at higher magnification in panel B. Osteoblasts, osteocytes and a pre-osteocyte are identified (panel B). The locations of the osteoid and the mineralization front (MF) are indicated (panel B). The black arrows in panel B point to the presence of purplish-blue-stained spherulites referred to in the text. Panels C–E: Transmission mode confocal microscopy images of the same tissue section shown in panels A and B above. The box in panel C identifies a region of interest at the mineralization front that is shown at higher magnification in panel D. White arrows in panel E point to the presence of dark-stained spherulites referred to in the text. Black arrowhead in panel E points to an apparent cell process of a newly embedded osteocyte projecting up into the osteoid layer. Ten confocal images such as that shown in panel E were reconstructed into three-dimensional volumes. Spherulite diameters in these combined three-dimensional volumes were determined using Image Pro 4.0 (Media Cybernetics, MA). A Gaussian fit of the data points was calculated by Origin 7.0 (Microcal) and displayed as a solid black profile.

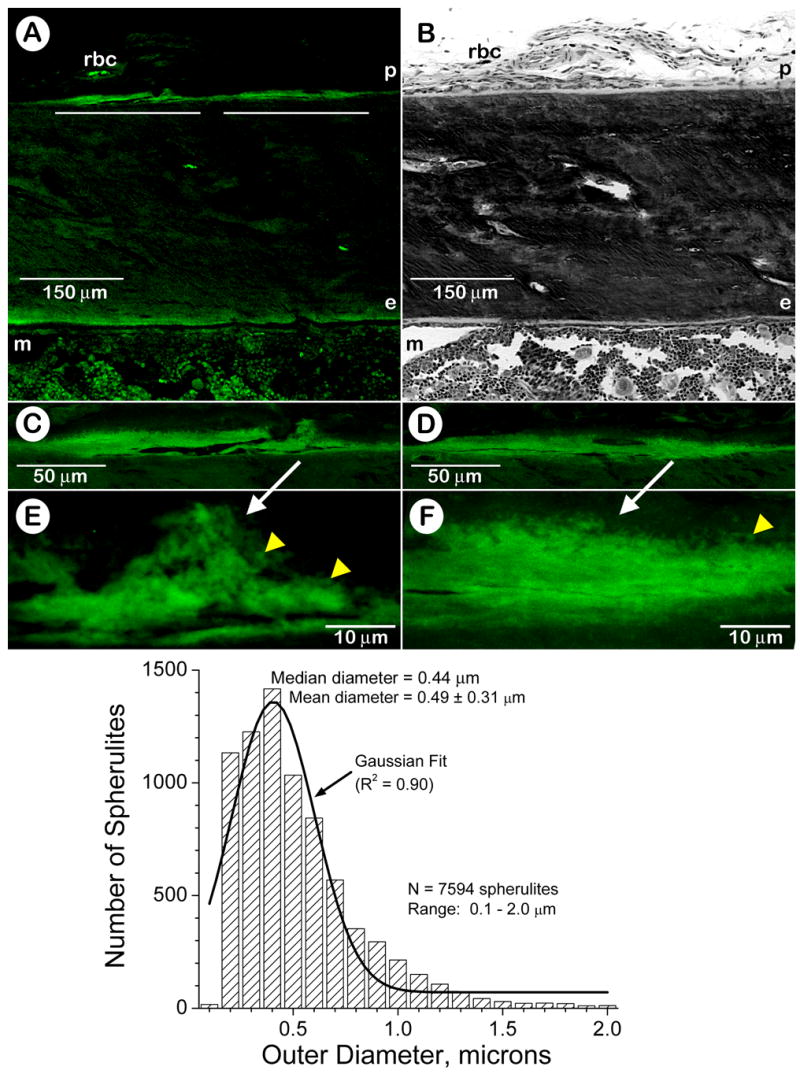

Mineralization Front Spherulites Are Located Near Newly Forming Bone Tissue

A limitation of the above histological approach is that it does not provide unambiguous data on whether these spherulites actually contain a mineral phase, and are located within newly formed bone matrix in vivo. A conventional approach to provide this definitive proof was sought using an injection of a calcium-binding dye (calcein) into live rats, which would first circulate in the blood and then bind and pulse-label the newly forming bone mineral phase along the surface of the mineralization front. A single injection of calcein into juvenile rats labeled both periosteal- and endosteal-mineralizing surfaces (Fig. 2A,B) [1]. Epifluorescence confocal microscopy revealed a calcein-labeled layer along the periosteal mineralization front (Fig. 2C,D), which appeared to be replete with calcein-labeled spherulites (Figs. 2E,F). Computer-aided morphometry indicated that these spherulites exhibited an average diameter of 0.49 ± 0.31 microns (Fig. 2, histogram). These calcein-labeled spherulites were frequently observed to cluster in focal matrix areas along the mineralization front (Fig. 2E, yellow arrowheads) in patterns and overall sizes resembling those of calcospherulites localized in biomineralization foci (BMFs) [20,21].

Fig. 2. The mineralization front along the periosteal surface of diaphyseal bone exhibits calcein-labeled spherulites.

Panel A: Epifluorescent confocal microscopy image of an undecalcified section of tibial diaphysis tissue from a juvenile male rat labeled in vivo with calcein (20X). Panel B: Brightfield microscopy image of a toluidine blue-stained section near, but not serial to, the section shown in panel A (20X). Some red blood cells (rbc) exhibiting autofluorescence are observed in a blood vessel within the nonosseous periosteum, and marrow tissue (m) also exhibits some autofluorescence. Periosteal (p) and endosteal (e) bone surfaces are denoted. The white lines in panel A identify regions of interest at the periosteal mineralization front that are shown at higher magnification in panels C and D left to right, respectively. Panels C and D: Epifluorescent confocal microscopy images of the periosteal mineralization front labeled in vivo with calcein (63X). Panels E and F: Epifluorescent confocal microscopy images of the periosteal mineralization front labeled in vivo with calcein (252X). The white arrows identify the locations of calein-labeled spherulites at or within the mineralization front along the periosteal surface of the diaphyseal cortex. Yellow arrowheads point to calcein-labeled spherulites at the mineralization front and many appear to cluster together in larger focal complexes. Twenty confocal images such as those shown in panels E and F were reconstructed into three-dimensional volumes. Spherulite diameters in these combined three-dimensional volumes were determined using Image Pro 4.0 (Media Cybernetics, MA). A Gaussian fit of the data points was calculated by Origin 7.0 (Microcal) and displayed as a solid black profile.

Mineralization Front Spherulites Contain Calcium (Calcospherulites) And Are Released By Dispase Digestion

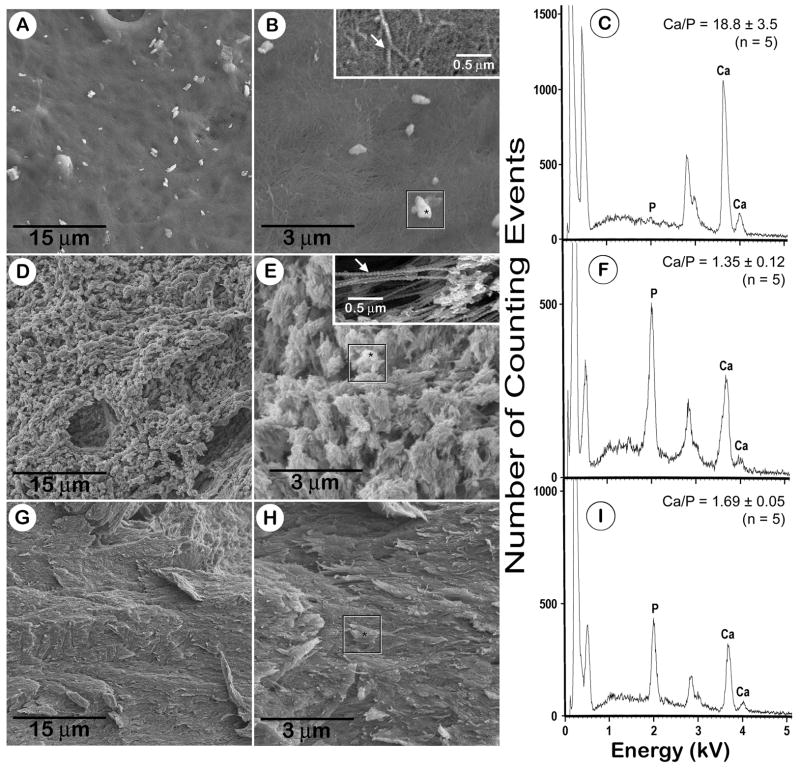

To confirm these findings, a scanning electron microscopy approach was used to characterize calcospherulites along the periosteal mineralization front of the tibial diaphysis. This method offered several advantages: minimized exposure to aqueous solutions to assure a better preservation of mineral phases, avoidance of embedding and sectioning which may introduce artifacts, and a higher optical resolution than either brightfield or confocal microscopy. Periosteal cell layers were dissected from tibial diaphyses prior to processing in order to reveal the underlying osteoid matrix layer (Figs. 3A,B). Images of the osteoid matrix surface showed a tightly woven, disorganized network of 60–80 nm-thick fibers, presumably type I collagen (Fig. 3B; inset). They also showed the presence of (sub)micron-sized particles, on average ~5 per 100 μm2, which seemed to be on top of, or partially embedded within, the fiber-rich matrix (Fig. 3B; box). In situ EDS analysis revealed that about one-third of these structures did not exhibit detectable amounts of calcium or phosphorus, and another third exhibited relatively small amounts of phosphorus but no calcium (data not shown). This analysis did detect calcium in the remaining third of these structures, and they exhibited an average Ca/P ratio of close to 19 (Fig. 3C). Given these results, it is quite possible that some of the particles on the surface of the osteoid matrix may be the result of residual protein precipitates resulting from the specimen drying process.

Fig. 3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) of the osteoid surface, the mineralization front, and of the underlying bone tissue after sequential processing.

Panels A and B are SEM images of the osteoid surface taken after periosteum dissection. The box in panel B identifies an osteoid-surface spherulite selected for EDS, and the included asterisk identifies the focus site for the electron beam. Inset image in panel B is a higher magnification view of the osteoid matrix, and the white arrow points to a 60–80 nm thick-banded fiber. Panel C shows an EDS profile for the osteoid-surface spherulite indicated in panel B (box); the calcium/phosphorus (Ca/P) ratio shown is the mean ± SD of 5 such spherulites. Panels D and E are SEM images of the mineralization front taken after collagenase digestion. The box in panel E identifies a mineralization-front spherulite selected for EDS, and the included asterisk identifies the focus site for the electron beam. Inset image in panel E is a higher magnification view of the banded fibers interconnecting the spherulites, and the white arrow points to a 60–80 nm thick-banded fiber. Panel F shows an EDS profile for the mineralization-front spherulite indicated in panel E (box); the Ca/P ratio shown is the mean ± SD of 5 such spherulites. Panels G and H are SEM images of the bone surface taken after dispase digestion. The box in panel H identifies a bone area selected for EDS, and the included asterisk identifies the focus site for the electron beam. Panel I shows an EDS profile for the bone surface area indicated in panel H (box); the Ca/P ratio shown is the mean ± SD of 5 such areas. The EDS signal at 0.5 kV is attributed to oxygen. The doublet signal at 2.8 kV and 3.0 kV are attributed to palladium, and was used as an internal standard.

Osteoid extracellular matrix consists in large part of unmineralized and poorly mineralized type I collagen fibers. Accordingly, periosteum-denuded specimens were digested with highly purified collagenase digestion prior to processing in order to remove the unmineralized osteoid layer and expose the underlying mineralization front interface at the periosteal bone surface. Images of the mineralization front interface showed numerous calcospherulites (Fig. 3D) exhibiting ~ 100–200 spherulites per 100 μm2 having an average diameter calculated to be 0.47 ± 0.22 microns (Fig. 3E; n = 1626 counted). These images also revealed the presence of 60–80 nm-thick banded fibers within the matrix spaces between calcospherulites (Fig. 3E; inset). EDS analysis of these collagenase digested specimens confirmed that these calcospherulites exhibited detectable amounts of calcium and phosphorus having an average Ca/P ratio of 1.35 (Fig. 3F).

The presence of banded fibers within the matrix spaces between spherulites suggested the presence of complexes of extracellular matrix molecules resistant to collagenase digestion. These complexes likely consist of partially mineralized type I collagen, collagenase-resistant collagens (such as types V and XI), and noncollagenous proteins. To test this rationale, specimens submitted to periosteal disssection and collagenase digestion were then subsequently treated with dispase (non-specific, serine protease) in an attempt to disrupt these presumptive matrix protein complexes, and release calcospherulites from the mineralization front. Images after dispase digestion demonstrated the quantitative removal of the mineralization front-calcospherulites along with the banded fibers (Fig. 3G), and revealed overlapping plate-like structures having approximately similar size area as the released calcospherulites (Fig. 3H; box). EDS analysis of these overlapping plate-like structures yielded an average Ca/P ratio of 1.69 (Fig. 3I).

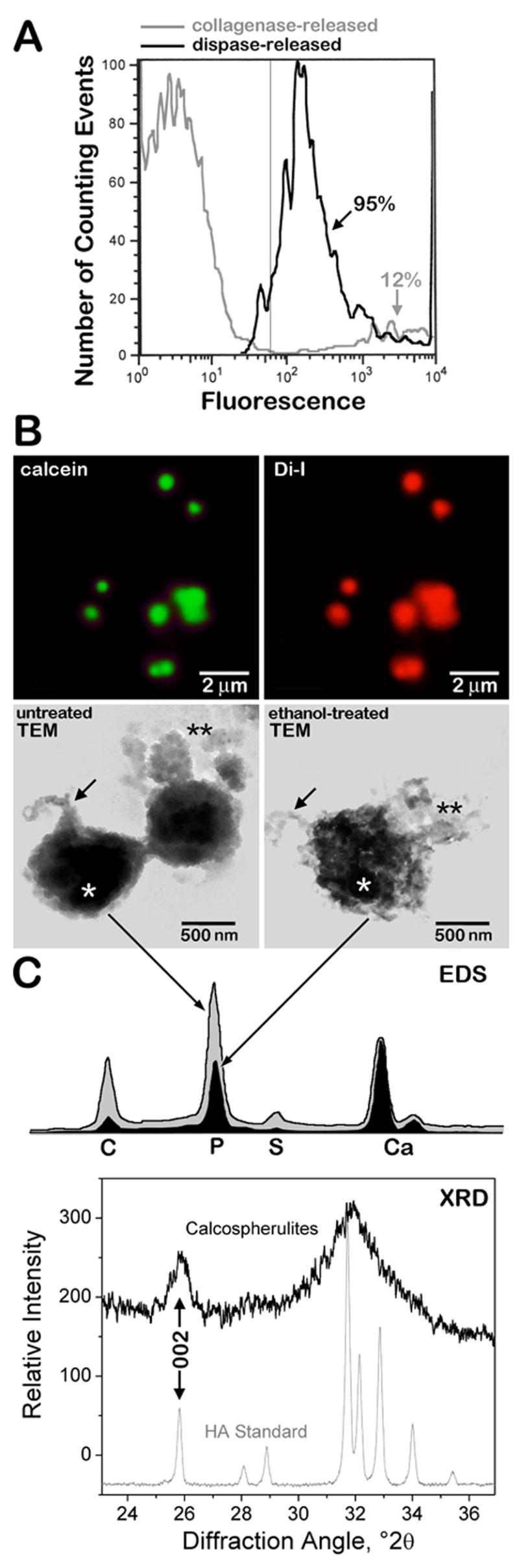

Dispase Released Calcospherulites Can Be Isolated By Fluorescence-Activated Flow Sorting

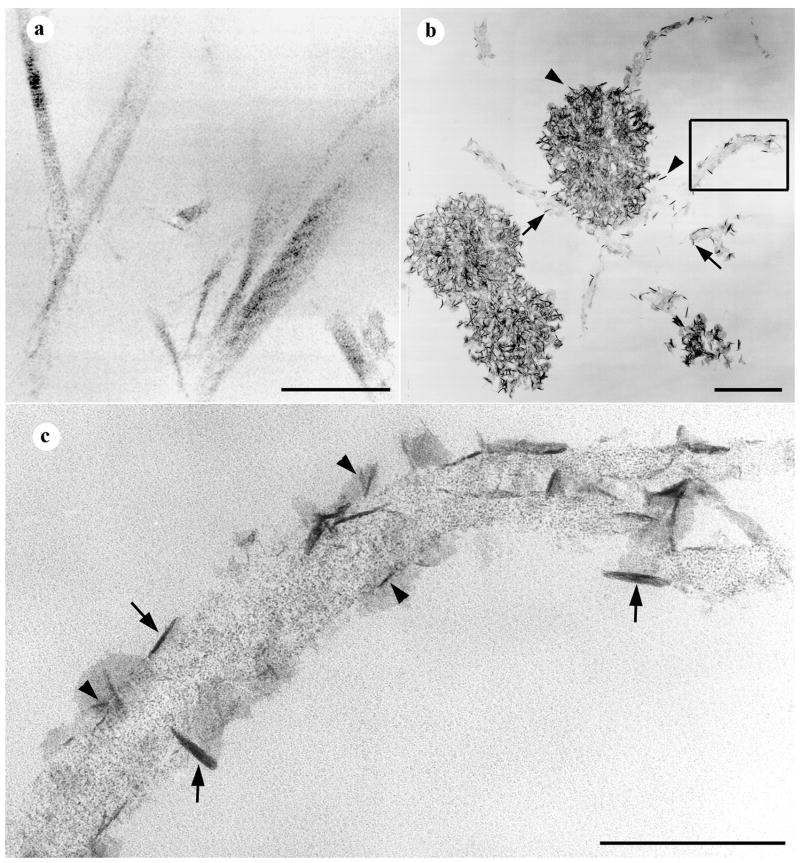

The data in Figure 3 indicated that a sequential protease digestion procedure was able to effectively remove calcospherulites from the mineralization front of periosteal bone. We sought to isolate these released calcospherulites via fluorescence sorting and centrifugation. Using a size-gating setting of less than 3 microns, fluorescence flow sorting indicated the ample presence of calcein-labeled calcospherulites released by collagenase/dispase digestion, but relatively few released by collagenase digestion alone (Fig. 4A). Calcospherulites flow sorted from dispase digests were pelleted at 30,000 g, then resuspended and spotted onto coverslips for examination by confocal microscopy. Such imaging revealed the presence of calcein-labeled calcospherulites many of which appeared to be ~ 0.5 micron in diameter (Fig. 4B; calcein). This same material when spotted onto carbon-coated, electron microscopy grids and imaged in whole-mount TEM confirmed the presence of calcospherulites slightly larger than 0.5 micron in diameter (Fig. 4B; untreated TEM). These same images revealed the presence of filamentous structures having diameters of 60–80 nm (Fig. 4B; untreated TEM, arrow), and the occasional presence of more diffuse matrix materials (black double asterisks) both of which were observed in proximity to some of the calcospherulites. EDS analysis of these isolated calcospherulites revealed a Ca/P ratio of ~ 1.3 (Fig. 4C; EDS, gray profile). X-ray diffraction analysis of a separate preparation of isolated calcospherulites revealed the presence of two distinct peaks (26° and 32° 2θ) with a less distinct series of peaks between them (Fig. 4C, XRD profile). Using the width of the half maximal height of the 26° 2θ (002) diffraction peak, the crystal c-axis size was determined using Scherrer’s equation [26]. This analysis demonstrated that isolated calcospherulites contained a poorly crystalline apatite mineral phase having an average c-axis crystal length that was calculated to be 17.5 ± 0.2 nm 2.

Fig. 4. Fluorescence-flow sorting isolation and preliminary structural characterization of calcospherulites.

Panel A: Beads of 3 μm in outer diameter were used to calibrate the fluorescence flow sorting runs, and their intensity was used to segment the level of positive fluorescence (to the right of the thin gray line at 60 relative fluorescence units). Gray profile shows the fluorescence flow sorting of the collagenase-released spherulites (osteoid matrix); approximately 12% of the total counting events were scored above the background level. Black profile shows the fluorescence flow sorting of the dispase-released spherulites (mineralization front matrix); approximately 95% of the total counting events were scored above the background level. Panel B: Top two images show epifluorescence confocal microscopy images of resuspended mineralization-front spherulites recovered by calcein-fluorescence sorting and centrifugation, stained with dialkyene carbocyanine dye I (Di-I), and spotted onto a coverslip. Calcein and Di-I panels are fluorescence emission data specific for calcein and Di-I, respectively. Middle two images show transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of resuspended mineralization-front spherulites recovered by calcein-fluorescence sorting followed by centrifugation, and spotted onto carbon-coated copper grids without (untreated) or with a 30 min. treatment with 70% ethanol at 4° C (ethanol-treated). Note the presence of filamentous material (black arrows) and amorphous material (black double-asterisks) associated with the spherulites before and after ethanol treatment. Panel C: EDS image shows the profiles for isolated spherulites shown in the above TEM panels (white asterisks indicate the position of the electron beam) analyzed before (gray shaded) and after (black shaded) cold ethanol treatment. Element abbreviations are provided. Ca/P ratios averaged 1.29 ± 0.15 before, and 1.59 ± 0.08 after ethanol treatment (mean ± SD; n = 5 each; p < 0.05 by ANOVA). XRD image shows the diffraction profiles for a preparation of isolated calcospherulites (black) and that of a synthetic hydroxyapatite standard (gray). The 002-peak is indicated for each profile.

Isolated Calcospherulites Likely Contain Phospholipids

The Ca/P ratios of these isolated calcospherulites was less than the theoretical 1.67 value expected for pure hydroxyapatite, which suggested the presence of organic phosphorus containing compounds. Possible explanations for this organic phosphorus would be the presence of phospholipids and/or phosphoproteins. Two approaches were undertaken to address whether isolated calcospherulites contain phospholipids. One approach utilized the ability of dialkene carbocyanine dyes to intercalate or associate via strong hydrophobic interactions with lipophilic molecules. Confocal imaging of isolated calcospherulites revealed that nearly all of them stained strongly positive with dialkene carbocyanine I (Fig. 4B; Di-I). A second approach consisted of treating isolated calcospherulites on electron microscopy grids with ice-cold 70% ethanol in order to selectively remove phospholipids (Fig. 4B; ethanol-treated TEM) [27,28], and submitting them to EDS. Such analysis revealed the presence of ethanol-extractable phosphorus from isolated calcospherulites (Fig. 4B; EDS, black profile) suggesting that phospholipids are likely to be associated with calcospherulites.

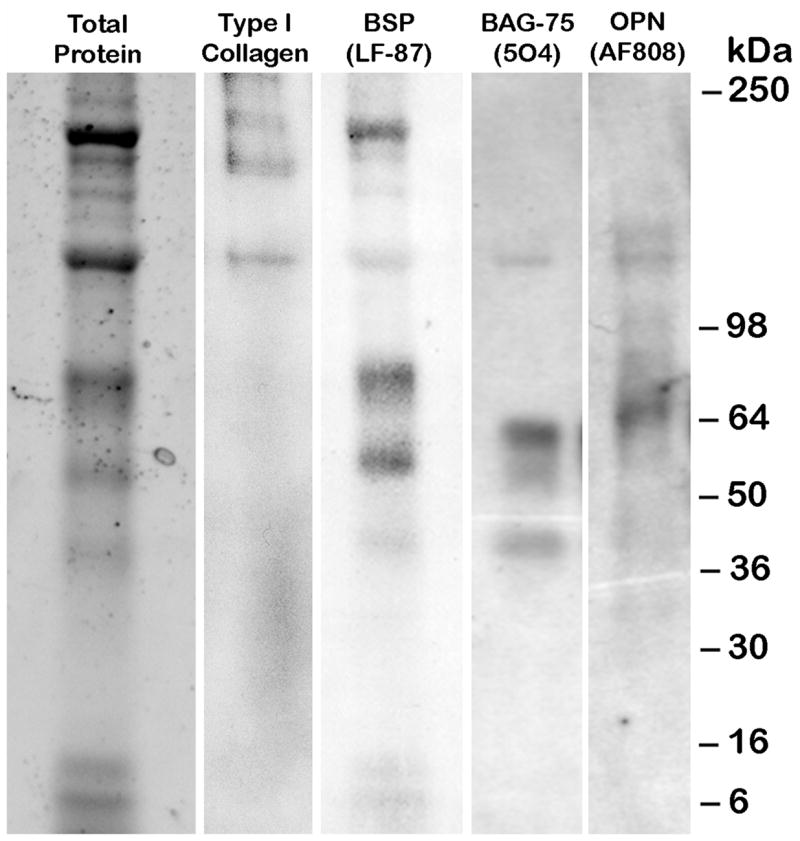

Isolated Calcospherulites Contain Phosphoproteins

A Western blot approach was undertaken to address whether isolated calcospherulites contain extracellular matrix phosphoproteins. As shown in Fig. 5 (Total Protein lane), protein extracts from isolated calcospherulites exhibited about 15–20 distinct bands when analyzed by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. This profile distributed into two prominent bands (240 and 120 kDa), 6 major bands (230, 220, 75, 55, 12 and 10 kDa), and several relatively minor intensity bands. Western blot analysis (Fig. 5) revealed the presence of the following bone matrix phosphoproteins: bone sialoprotein (BSP), osteopontin (OPN), and bone acidic glycoprotein-75 (BAG-75). Major stained bands at 75, 55, 12 and 10 kDa in this protein extract correlated well with similar-sized bands seen in the BSP Western blot and likely represent intact monomer and several known proteolytic cleavage products of BSP [29]. Additionally, Western blot analysis revealed isolated calcospherulites contained both mature and partially processed type I collagen α-chains, which may account for some of the 60–80 nm diameter filaments associated with isolated calcospherulites (Fig. 4B; untreated TEM). Larger sized forms of BAG-75, BSP, and OPN were also detected, which at least for the later two, may represent transglutaminase cross-linked complexes [30].

Fig. 5. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated bone matrix proteins extracted from isolated calcospherulites.

See-Blue molecular weight (MW) marker migration positions are indicated. Western signals for the expected mature type I collagen bands, α1(I) and α2(I), are observed as a tight doublet at ~120 kDa, while the higher MW doublets likely represent partially processed procollagen molecules. Western signals for the expected mature BSP (75 kDa), BAG-75 (57 kDa), and OPN (66 kDa) were observed. The lower MW signals in the BSP Western blot likely represent known BSP breakdown products [20]. The higher MW signals in the BSP and OPN Western blots likely represent known transglutaminase-cross linked multimers of these respective matrix proteins [21].

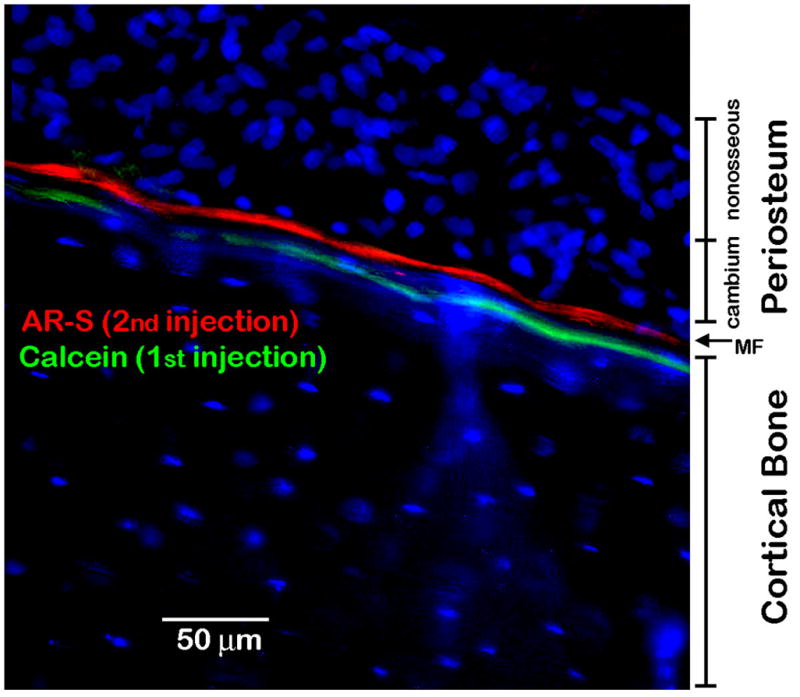

Calcospherulites May Become Trapped In Newly Forming Bone

In order to test whether calcein-labeled calcospherulites could be incorporated into cortical bone tissue, juvenile rats were first dynamically labeled with calcein and then, 3 days later, with alizarin red-S. Sixteen hours after the AR-S injection, the tibial diaphysis was recovered for hard tissue sectioning and epifluorescent microscopic imaging (Fig. 6). After 3 days of additional growth, the alizarin red-S labeling line identifies the current position of the mineralization front, while the original calcein labeling line is located well beneath it. The average distance separating the calcein and alizarin red-S labeling lines was ~8 μm, and is proportional to the amount of new bone depoited over this time interval. These data indicate that some of the calcein label from the mineralization front has become incorporated into the underlying cortical bone tissue, and suggests that some of the labeled calcospherulites may have also become trapped in this bone tissue.

Fig. 6. Calcein-label becomes embedded into cortical bone tissue within a few days.

Rats were first injected with calcein, and followed 3 days later with an injection of alizarin red-S. The locations of the cambium (osseous) and non-osseous periosteal cell layers are indicated. The current mineralization front (MF) is indicated as the position of the AR-S labeling line, and the location of the underlying cortical bone is also indicated. Note that the calcein labeling line has become stably incorporated into the underlying cortical bone tissue.

Isolated Calcospherulites Seed The Calcification Of Collagen Hydrogels

If calcospherulites function physiologically in the nucleation of apatite in growing bone, then we hypothesize that a subsequent growth and expansion of their mineral phase should occur in the surrounding collagenous matrix. We tested this possibility by directly mixing isolated calcospherulites with type I collagen immediately prior to reconstitution of a fibrillar collagen matrix, and comparing it to controls that substituted buffer alone for the calcospherulites. Calcopherulites did not alter the fibrillogenesis reaction as the collagen fiber thickness ranged from 55–95 nm in their absence (Fig. 7A) or presence (Fig. 7B). After 72 h exposure, collagen gels without calcospherulites were devoid of plate- or needle-like crystals on the type I collagen fibers (Fig. 7A). In contrast, collagen fibers co-incubated with calcospherulites had numerous plate- or needle-like crystals decorating the type I collagen fibers (Fig. 7B). In some cases, these “crystals” appeared aligned with the fiber’s long axis, and they distributed themselves along much of the visible length of the fibrils rather than being concentrated in select regions (Fig. 7C). Indeed, some were observed on the collagen fibers more than 0.5 microns away from the nearest calcospherulite (Fig. 7B). We conclude that isolated calcospherulites can induce or seed the formation of mineral crystals on reconstituted collagen fibers.

Fig. 7. Isolated calcospherulites seed a mineralization reaction on reconstituted native type I collagen fibers in vitro.

All images are transmission electron micrographs of ultra-thin sections through collagen hydrogel plastic blocks. Panel A: No crystals are seen in the control photomicrograph of collagen fibers alone (scale bar = 300 nm). Panel B: photomicrograph of calcospherulites and collagen fibers (scale bar = 200 nm). Crystals are identified on calcospherulites (arrowheads) and collagen fibers (arrows). The box in panel B designates a single calcified collagen fiber shown at higher magnification in panel C. Panel C: “Short” (arrowheads) and “long” crystal lengths (arrows) on a collagen fiber are identified (scale bar = 200 nm).

Discussion

The mineralization front of bone is central to an understanding of the physiological process of bone formation, as it represents the dynamic interface between poorly and fully mineralized extracellular matrix. The data presented herein support the following conclusions about the structure and function of calcospherulites at the bone mineralization front. First, consistent with previous findings [10], the periosteal mineralization front of the juvenile rat tibial diaphysis exhibited numerous calcospherulites having an average diameter of ~0.5 micron and a Ca/P ratio of 1.3 in situ. Second, these spherulites were shown to actively participate in the mineralization process in vivo since they were intensely labeled with a calcium-binding fluorochrome (calcein) within 24 h after injection into live rats. Third, calcein-labeled calcospherulites were released from the exposed mineralization front by protease treatment and isolated by fluorescence flow sorting. Fourth, EDS and XRD analyses of isolated calcospherulites revealed the presence of a poorly mineralized apatite containing a Ca/P ratio of 1.3 and c-axis crystal lengths consistent with those previously reported for young rat bone [25,31]. A portion of the non-mineral phosphorous content of these preparations may be attributable to the presence of phospholipids since a brief extraction with ethanol elevated the mean Ca/P ratio to 1.6, close to that of pure hydroxyapatite. Fifth, Western blot analyses showed isolated calcospherulites contained BSP, a bone matrix protein considered to possess mineral nucleation properties [22]. Finally, incubating isolated calcospherulites in collagen hydrogels demonstrated that they could seed a mineralization reaction on type I collagen fibers in vitro while buffer controls were negative. Altogether, these conclusions directly support an active role for calcospherulites in promoting the crystallization of type I collagen fibers at the mineralization front of bone.

Several other groups have reported the presence of discrete spherical or ovoid shaped entities at the mineralization front of bone having similar structural and elemental characteristics to what is described in the current study [11–19,32,33]. A unique contribution of the present study to this existing literature is the isolation and initial biochemical characterization of these mineralization front structures. Based on a conventional approach to dynamically label newly forming bone tissue, there is a high confidence that these isolated calcospherulites were associated with the newly formed bone tissue at the mineralization front. In contrast to a previous report that used repeated, high-dose tetracycline labeling in vivo to severely inhibit growth plate mineralization (6 injections of 100 mg/kg each) [34], our in vivo labeling method used a single, low-dose (10 mg/kg) injection of calcein. Proof that this calcein injection did not overtly inhibit mineralization was revealed when some of the original calcein labeling line became incorporated into the underlying bone tissue within a few days of subsequent growth. Given that some of the calcein-label at the mineralization front becomes incorporated into the underlying bone over time, it is quite possible that some of the organic contents of the calcospherulites may also become trapped in the underlying bone tissue. With this calcospherulite isolation method in place, we are now poised to investigate the proteomics of their structural and functional attributes.

Calcospherulites have been observed near the mineralization front of healing bone tissue [35] including an in vivo model of bone injury repair referred to as marrow ablation [36]. Recently, using this marrow ablation model, we have reported the preferential clustering of newly formed calcospherulites within select areas of extracellular matrix referred to as biomineralization foci (BMFs) [20]. This study revealed that the location of a bone matrix protein (BAG-75) defines the future boundaries of BMFs because BAG-75 deposition temporally preceded the appearance of calcospherulites and mineral deposition in this bone repair model [20], and predicted the extracellular matrix regions that would subsequently mineralize. Significantly, the calcospherulites isolated from the mineralization front of periosteal bone also contained BSP and BAG-75 epitopes. Thus, several characteristics of calcospherulites along the mineralization front of growing diaphyseal bone are similar to the characteristics of calcospheruiltes located within BMFs identified in bone repair tissue, namely those of size and clustering pattern, of initial mineral crystal deposition, and presence of BSP and BAG-75.

It has been previously suggested that matrix vesicles may aggregate and transition to become calcospherulites [35]. Our studies revealed the presence of ethanol-extractable phosphorus in isolated calcospherulites, and future studies will identify and quantify the nature of this extractable phosphorus. Since nucleic acids, proteins, and complex carbohydrates are insoluble in cold ethanol solutions, then the most likely molecular candidate to explain this ethanol-extractable phosphorus would be phospholipids [27,28]. If true, then an apparent association of phospholipids with calcospherulites would be consistent with the concept that some type of matrix vesicle aggregation phenomenon could permit the transition of some of their contents to become calcospherulites [35].

Calcospherulites appeared in proximity to what appeared to be collagen fibers all along the periosteal mineralization front. This would suggest that they might be involved in a “seeding” reaction to calcify the type I collagen fibers thereby forming a transition state along the mineralization front. A direct test of this possibility was sought by incubating isolated calcospherulites in type I collagen hydrogels in vitro. Ultrastructural analysis revealed plate-like (or needle-like) structures on the collagen fibers and they were distributed along much of the visible length of the fibers rather than being concentrated only near the calcospherulites. In fact, some of these structures were observed on the collagen fibers well away from the nearest calcospherulite, and raise an interesting, and yet unanswered, question of how exactly this could occur. Thus, we conclude that isolated calcospherulites can induce the mineralization of type I collagen fibers in vitro. Another finding from these tests revealed that calcospherulites incubated in type I collagen gels take on an ultrastructural appearance similar to that of crystal ghost aggregates observed in vivo [9]. Since both our isolated calcospherulites and crystal ghost aggregates [13] contain BSP, then this ultrastructural similarity may not be coincidental and might suggest a structure/function identity. Altogether, the similarities between our in vitro results and observations made from in vivo samples suggest that calcospherulites likely mediate the mineralization of osteoid at the mineralization front of bone tissue in vivo.

Collagenase digestion effectively removed much of the osteoid extracellular matrix from the periosteal surface, yet some 60–80-nm fibers located at the mineralization-front appeared to resist this digestion reaction. We attribute this differential collagenase susceptibility to the likely presence of resistant molecules like type XI collagen or noncollagenous proteins [16], mineral crystals [17], and/or lipophilic material [37] associated with the fibers at the mineralization front. These components associated with any type I collagen fibers might provide an increased steric hinderance to collagenase, and possibily explain their increased resistance to degradation. Also, this interpretation of steric hindrance may be extended to explain how some of the protein content extracted from the isolated calcospherulites remained relatively intact after dispase digestion. Here, we propose that the mineral and/or lipid content on the outer surface of the calcospherulites may provide partial protection for the inner protein contents of these structures, thereby establishing a barrier to block the proteolytic actions of dispase [17]. In fact, this explanation would also account for our previous immunohistochemical observations that a large portion of BSP and BAG-75 epitopes in bone tissue sections [20] and mineralized osteoblast cultures [21] required decalcification to reveal them.

A question emerges about how these calcospherulites might form. Calcein-labeled calcospherulites were abundantly localized along the mineralization front, yet very few of them were detected within the overlying osteoid. This narrow spatial dimension suggests two potential cell sources for these structures: late-stage lining osteoblasts and/or early osteoid osteocytes. Late-stage lining osteoblasts could generate calcospherulites via the release of secretory bodies or vesicles that aggregate and assemble in focal matrix areas as described for several osteoblastic cell lines [21]. Alternatively, a pre-osteocyte cell line has been reported to bud off vesicles from its surface, which transform into small calcification spheres similar in shape, size, and calcium content to the calcospherulites reported here [19]. Spatial-temporal distinctions would seemingly exist between these two proposed biomineralization reactions, and likely reflect upon the calcium-sequestration processes in these two cell types. For pre-osteocyte cultures, vesicles and secretory granules have been reported to begin calcifying at the cell surface and within the pericellular matrix [19], while for mature osteoblast cultures they have been reported to calcify at distances further away from their cell surfaces, and well within the extracellular matrix boundaries [21]. It is not clear at present whether the vesicles from these two cell types are identical, and whether they are related to matrix vesicles isolated from calcifying cartilage. In addition, it is not known at present whether the calcified spherulites generated by these cell types share identity with calcospherulites isolated here from the mineralization front of juvenile long bones. Nevertheless, the presence of phospholipids and putative nucleator phosphoproteins associated with calcospherulites support the need to investigate further whether a direct comparison exists between these in vivo structures with those isolated from in vitro models.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Thomas Bauer and Diane Mahovik (Depts. of Anatomical Pathology and Orthopaedic Surgery, Cleveland Clinic) for their help with the hard tissue processing and sectioning included in this study. The authors also wish to thank Drs. Lynda Bonewald (Dept. of Oral Biology, University of Missouri-Kansas City) and Vincent Hascall (Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, Cleveland Clinic) for their critiques of this manuscript prior to submission. Funding for this study was provided by NIAMS, NIH grants to RJM (AR045171) and JPG (AR052775). Histology and microscopy services were provided by The Cleveland Clinic Musculoskeletal Core Center funded in part by NIAMS Core Center Grant #1P30 AR-050953.

Footnotes

Calcospherulites (calco: calcium salt + spherulite: spherical crystalline body); calcium-containing, spherical bodies have also been referred to as calcified microspheres, mineral clusters, crystal ghost aggregates, calcification nodules, calcospherites, and small calcified spheres.

Abbreviations used are: BAG-75 Bone acidic glycoprotein-75; BMF, biomineralization foci; BSP, bone sialoprotein; OPN, osteopontin; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; EDS, energy dispersive spectroscopy; XRD, X-ray diffraction; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TBS, Tris-buffered saline; Di-I, dialkene carbocyanine-I

Scherrer’s Equation: D = Kλ(57.3)/βcosθ; D = c-axis crystal length; K = 0.9 (geometric shape factor); λ = 0.154 nm (x-ray wavelength); θ = 12.99° (half the diffraction angle of the 002 peak); β = 0.463 (corrected line width using highly crystallized HA standard).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ronald J. Midura, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering and The Orthopaedic Research Center, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195

Amit Vasanji, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering and The Orthopaedic Research Center, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195.

Xiaowei Su, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering and The Orthopaedic Research Center, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195.

Aimin Wang, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering and The Orthopaedic Research Center, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195.

Sharon B. Midura, Dept. of Biomedical Engineering and The Orthopaedic Research Center, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195

Jeff P. Gorski, Dept. of Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri

References

- 1.Leblond CP, Wilkinson GW, Belanger LF, Robichon J. Radio-autographic visualization of bone formation in the rat. American Journal of Anatomy. 1950;86:289–299. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000860205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson HC. Matrix vesicles and calcification. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2003;5:222–226. doi: 10.1007/s11926-003-0071-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg M, Boskey AL. Lipids and biomineralizations. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 1997;31:1–187. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6336(96)80011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boskey AL. Biomineralization: Conflicts, Challenges, and Opportunities. J Cellular Biochem Suppl. 1998;30/31:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson HC. Molecular biology of matrix vesicles. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;314:266–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonucci E. Chapter 7, Section 3.5 “Matrix Vesicles”. In: Schreck S, editor. Biological Calcification -Normal and Pathological Processes in the Early Stages. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin; 2007. pp. 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christoffersen J, Landis WJ. A contribution with review to the description of mineralization of bone and other calcified tissues in vivo. Anatomical Record. 1991;230:435–450. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyde A, Sela J. Scanning electron microscope study of separated calcospherites from the matrices of different mineralizing systems. Calcified Tissue Research. 1978;26:47–49. doi: 10.1007/BF02013233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonucci E. Comments on the ultrastructural morphology of the calcification process: an attempt to reconcile matrix vesicles, collagen fibrils, and crystal ghosts. Bone & Mineral. 1992;17:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ornoy A, Atkin I, Levy J. Ultrastructural studies on the origin and structure of matrix vesicles in bone of young rats. Acta Anatomica. 1980;106(4):450–61. doi: 10.1159/000145214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonucci E. Ultrastructural organic-inorganic relationships in calcified tissues: cartilage and bone versus enamel. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;33:157–162. doi: 10.3109/03008209509016996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ecarot-Charrier B, Shepard N, Charette G, Grynpas M, Glorieux FH. Mineralization in osteoblast cultures: a light and electron microscopic study. Bone. 1988;9:147–154. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(88)90004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianco P, Riminucci M, Silvestrini G, Bonucci E, Termine JD, Fisher LW, Gehron Robey P. Localization of bone sialoprotein (BSP) to golgi and post-golgi secretory structures in osteoblasts and to discrete sites in early bone matrix. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:193–203. doi: 10.1177/41.2.8419459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishima H, Kunuki Y, Sakae T, Kozawa Y, Watabe N. Calcospherites in rabbit incisor predentin. Scanning Microscopy. 1993;7:255–64. 264–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter DH, Hatton PV, Aaron JE. The ultrastructure of slam-frozen bone mineral. Histochem J. 1997;29:783–793. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425404169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter DH, Scully AJ, Davies RM, Aaron JE. Evidence for phosphoprotein microspheres in bone. Histochem J. 1998;30:677–686. doi: 10.1023/a:1003490506980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaron JE, Oliver B, Clarke N, Carter DH. Calcified microspheres as biological entities and their isolation from bone. Histochem J. 1999;31:455–470. doi: 10.1023/a:1003707909842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonucci E. Crystal ghosts and biological mineralization: fancy spectres in an old castle, or neglected structures worthy of belief? J Bone Miner Metab. 2002;20:249–265. doi: 10.1007/s007740200037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barragan-Adjemian C, Nicolella D, Dusevich V, Dallas MR, Eick JD, Bonewald LF. Mechanism by Which MLO-A5 Late Osteoblast/Early Osteocytes Mineralize in Culture: Similarities with Mineralization of Lamellar Bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;79:340–353. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorski JP, Wang A, Lovitch D, Law D, Powell K, Midura RJ. Extracellular bone acidic glycoprotein-75 defines condensed mesenchyme regions to be mineralized and localizes with bone sialoprotein during intramembanous bone formation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25455–25463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Midura RJ, Wang A, Lovitch D, Law D, Powell K, Gorski JP. Bone acidic glycoprotein-75 delineates the extracellular sites of future bone sialoprotein accumulation and apatite nucleation in osteoblastic cultures. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25464–25472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter GK, Goldberg HA. Nucleation of hydroxyapatite by bone sialoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8562–8565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher LW, Stubbs JT, III, Young MF. Antisera and cDNA probes to human and certain animal model bone matrix noncollagenous proteins. Acta Orthop Scand (suppl 66) 1995;66:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Midura RJ, Su X, Morcuende JA, Tammi M, Tammi R. Parathyroid hormone rapidly stimulates hyaluronan synthesis by periosteal osteoblasts in the tibial diaphysis of the growing rat. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51462–51468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanford CM, Jacobson PA, Eanes ED, Lembke LA, Midura RJ. Rapidly forming apatitic mineral in an osteoblastic cell line (UMR 106-01 BSP) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9420–9428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klug HP, Alexander LE. X-ray Diffraction Procedures. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nurminen M, Vaara M. Methanol Extracts LPS from Deep Rough Bacteria. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;219:441–444. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C-H, Vyavahare N, Zand R, Kruth H, Schoen FJ, Bianco R, Levy RJ. Inhibition of aortic wall calcification in bioprosthetic heart valves by ethanol pretreatment: Biochemical and biophysical mechanisms. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;42:30–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199810)42:1<30::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintz KP, Grzesik WJ, Midura RJ, Gehron Robey P, Termine JD, Fisher LW. Purification and Fragmentation of Nondenatured Bone Sialoprotein: Evidence for a Cryptic, RGD-Resistent Cell Attachment Domain. J Bone and Mineral Res. 1993;8:985–995. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaartinen MT, El-Maadawy S, Rasanen NH, McKee MD. Tissue transglutaminase and its substrates in bone. J Bone & Mineral Res. 2002;17:2161–2173. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arsenault AL, Grynpas MD. Crystals in calcified epiphyseal cartilage and cortical bone in the rat. Calcif Tissue Int. 1988;43:219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF02555138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martino LJ, Yeager VL, Taylor JJ. An ultrastructural study of the role of calcification nodules in the mineralization of woven bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 1979;27:57–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02441162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerman B. Changes in glycosaminoglycan binding to collagen during desmoid mineralization as revealed by different electron-microscopic staining techniques. Acta Anat. 1992;145:277–282. doi: 10.1159/000147377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy J, Ornoy A, Atkin I. Influence of tetracycline on the calcification of epiphyseal rat cartilage. Transmission and scanning electron-microscopic studies. Acta Anatomica. 1980;106:360–369. doi: 10.1159/000145201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sela J, Bab IA. Correlative transmission and scanning electron microscopy of the initial mineralization of healing alveolar bone in rats. Acta Anat. 1979;105:401–408. doi: 10.1159/000145146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sela J, Schwartz Z, Amir D, Swain LD, Boyan BD. The effect of bone injury on extracellular matrix vesicle proliferation and mineral formation. Bone & Mineral. 1992;17:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90729-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu LN, Genge BR, Lloyd GC, Wuthier RE. Collagen-binding proteins in collagenase-released matrix vesicles from cartilage. Interaction between matrix vesicle proteins and different types of collagen. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1195–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]