Abstract

There are currently no FDA-approved broth microdilution antifungal susceptibility testing products or interpretive breakpoints for susceptibility testing of the new triazole posaconazole. Fluconazole and voriconazole are in the same triazole class as posaconazole, have CLSI-approved interpretive MIC breakpoints, and are available on some commercially available MIC panels. We investigated whether one or both of these agents may be useful as a surrogate marker for posaconazole susceptibility. Fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole MIC results for 10,807 isolates of Candida spp. were analyzed to validate a potential surrogate marker for posaconazole activity against indicated species. For illustrative purposes, we applied the voriconazole MIC breakpoints to posaconazole (susceptible, ≤1 μg/ml; susceptible dose dependent, 2 μg/ml; resistant, ≥4 μg/ml) and compared these MIC results and categorical interpretations with those of fluconazole and voriconazole by using regression statistics and categorical agreement. For all 10,807 isolates, the absolute categorical agreement was 91.1% (0.1% very major errors [VME], 1.2% major errors [ME], and 7.6% minor errors [M]) using fluconazole as the surrogate marker and 97.7% (0.3% VME 0.1% ME, and 1.9% M) using voriconazole as the surrogate. The results with fluconazole improved to a categorical agreement of 93.7% (0.1% VME, 0.2% ME, and 6.0% M) when results for Candida krusei (not indicated for fluconazole testing) were omitted. Either fluconazole or voriconazole MIC results may serve as surrogate markers to predict the susceptibility of Candida spp. to posaconazole.

Posaconazole is a new triazole antifungal agent with broad-spectrum activity against Candida spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus spp., and other opportunistic and endemic fungal pathogens (6, 7, 9, 13, 18, 24, 28, 36, 37, 41). The activity of posaconazole against Candida spp. has been documented in vitro by the broth microdilution (BMD) (6, 24, 28, 41), disk diffusion, and Etest (AB BIODISK, Solna, Sweden) methods (8, 44). Although posaconazole is active against isolates of Candida spp. with decreased susceptibility to fluconazole, evidence of cross-resistance has been demonstrated, especially with fluconazole-resistant strains of C. glabrata (18, 24, 25, 28, 41).

Posaconazole has therapeutic indications for salvage therapy of invasive aspergillosis, fusariosis, chromoblastomycosis, and coccidioidomycosis (1, 39, 46, 49). It is also indicated as first-line therapy for oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) (45, 48) and for prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in neutropenia and in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients (5, 47). Although the emergence of fungi with reduced susceptibility to posaconazole was not detected during the treatment of OPC (45, 48) or the invasive fungal infection prophylaxis study periods (5, 47), the development of resistance remains a concern with both prophylaxis and OPC therapy and warrants further investigation.

Although both agar-based and BMD antifungal susceptibility testing methods have been validated for testing posaconazole against Candida (8), the immediate lack of commercial antifungal susceptibility testing products and interpretive breakpoints for susceptibility testing of this agent requires a surrogate marker agent to assist microbiologists and clinicians in the correct categorization of potentially indicated species of Candida (15, 16, 30, 35). The facts that both fluconazole and voriconazole are in the same triazole class as posaconazole, have Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)-approved MIC interpretive breakpoints (32, 33), and are available on some commercially available MIC panels (10, 19, 29, 34, 38) suggest that one or both of these agents may be useful as a surrogate marker for posaconazole susceptibility.

The purposes of the present study were to provide further documentation of cross-resistance among fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole and to examine the usefulness of both fluconazole and voriconazole as surrogate markers for evaluating posaconazole susceptibility in Candida spp. by using a large database of MIC results compiled in the course of global antifungal surveillance studies (26-28, 35).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

A total of 10,807 clinical isolates of Candida spp. submitted by more than 100 medical centers worldwide from January 2001 to December 2006 were tested. The collection included 5,827 Candida albicans isolates, 1,542 Candida parapsilosis isolates, 1,517 Candida glabrata isolates, 1,198 Candida tropicalis isolates, 305 Candida krusei isolates, 138 Candida guilliermondii isolates, 133 Candida lusitaniae isolates, 51 Candida kefyr isolates, 31 Candida pelliculosa isolates, 19 Candida famata isolates, 13 Candida rugosa isolates, 12 Candida dubliniensis isolates, 12 Candida lipolytica isolates, and 8 Candida zeylanoides isolates. All of these isolates were incident isolates from individual patients and were obtained from blood or other normally sterile body fluids. Isolates were identified by using Vitek and API yeast identification systems (bioMérieux, Inc., Hazelwood, MO) and were supplemented by conventional methods as needed (14). Isolates were stored as water suspensions until they were used. Prior to testing, each isolate was passaged at least twice on potato dextrose agar (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and CHROMagar (Hardy Laboratories, Santa Maria, CA) to ensure purity and viability.

Susceptibility testing.

Reference antifungal susceptibility testing of all isolates was performed by BMD as described by the CLSI (20). Reference powders of fluconazole (Pfizer), voriconazole (Pfizer), and posaconazole (Schering-Plough) were obtained from their respective manufacturers.

MIC interpretive criteria for fluconazole and voriconazole were those published by Pfaller et al. (32, 33) and the CLSI (20). Breakpoints were as follows: susceptible (S), ≤8 μg/ml (fluconazole) and ≤1 μg/ml (voriconazole); susceptible dose dependent (SDD), 16 to 32 μg/ml (fluconazole) and 2 μg/ml (voriconazole); resistant (R), ≥64 μg/ml (fluconazole) and ≥4 μg/ml (voriconazole). Posaconazole has not been assigned interpretive breakpoints by the CLSI. For purposes of comparison, we applied the MIC breakpoints listed above for voriconazole, i.e., ≤1 μg/ml (S), 2 μg/ml (SDD), and ≥4 μg/ml (R).

Analysis of results.

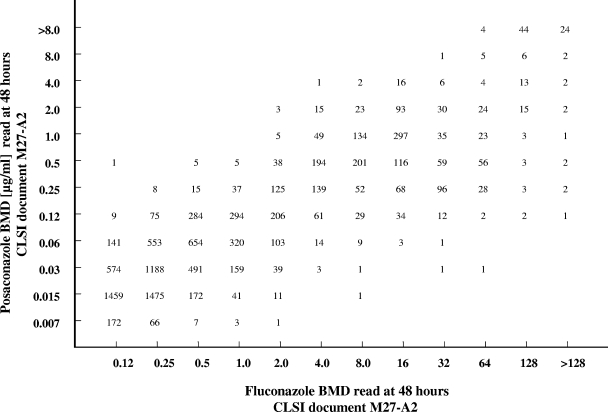

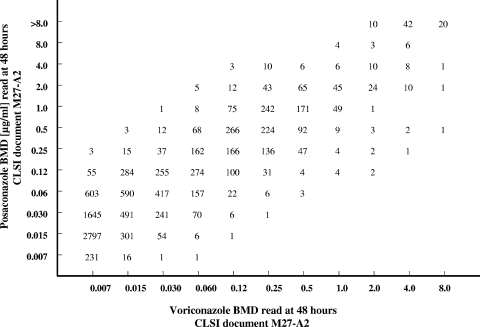

All MICs (expressed in micrograms per milliliter) of fluconazole and voriconazole were directly compared with those of posaconazole by using regression statistics and a scattergram (Fig. 1 and 2). Acceptable error limits used in this comparison were those cited by the CLSI and by other authors (4, 11, 16).

FIG. 1.

Scattergram comparing fluconazole and posaconazole MICs for 10,807 strains of Candida spp. An excellent correlation was observed (r = 0.88; y = 0.7425x − 1.3048).

FIG. 2.

Scattergram comparing voriconazole and posaconazole MICs for 10,803 strains of Candida spp. An excellent correlation was observed (r = 0.89; y = 0.8964x + 1.7269).

The definitions of errors used in this analysis were as follows: a very major error (VME), or a false-susceptible error, was a result of S for the surrogate marker fluconazole or voriconazole and a result of R for posaconazole; a major error (ME), or a false-resistant error, was a result of R for fluconazole or voriconazole and a result of S for posaconazole; and minor errors occurred when the result for one of the agents was S or R and that for the other agent was SDD. In general, for an agent to be considered a reliable surrogate, the VME rate should be ≤1.5% of all results and the absolute categorical agreement between methods should be ≥90% (4, 11, 16).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 depicts the MIC profiles and percentages of S and R for fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole determined for 10,807 strains of Candida spp. by using CLSI-validated BMD methods (20). Overall, 9,667 isolates (89.5%) were S, 868 (8.0%) were SDD, and 272 (2.5%) were categorized as R to fluconazole. Likewise, 10,656 isolates (98.6%) were S, 55 (0.5%) were SDD, and 92 (0.9%) were categorized as R to voriconazole. By comparison, 10,472 isolates (96.9%) were S, 205 (1.9%) were SDD, and 130 (1.2%) were R to posaconazole at MIC breakpoints of ≤1 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml, and ≥4 μg/ml, respectively. The modal MIC for posaconazole was 0.015 μg/ml, compared to 0.25 μg/ml for fluconazole and 0.007 μg/ml for voriconazole. Decreased potencies for all three agents were observed among C. glabrata (modal MICs of 1 μg/ml, 16 μg/ml, and 0.25 μg/ml for posaconazole, fluconazole, and voriconazole, respectively) and C. krusei isolates were susceptible to both posaconazole and voriconazole at ≤1 μg/ml. Aside from C. glabrata and C. krusei, decreased susceptibility (<90%) to fluconazole was noted among isolates of C. rugosa (61.5% S) and C. zeylanoides (87.5% S). C. glabrata (79.6% S), C. pelliculosa (58.1% S), and C. zeylanoides (87.5% S) showed decreased susceptibility to posaconazole, whereas decreased susceptibility to voriconazole was only seen with C. zeylanoides (87.5% S).

TABLE 1.

Comparative in vitro susceptibilities of more than 10,000 clinical isolates of Candida species to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole determined by CLSI methods

| Species | Antifungal agent | No. of isolates tested | MIC (μg/ml)

|

% S | % R | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% of isolates | 90% of isolates | |||||

| C. albicans | Fluconazole | 5,827 | 0.12->128 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 99.3 | 0.1 |

| Voriconazole | 5,826 | 0.007-4 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 99.9 | <0.1 | |

| Posaconazole | 5,827 | 0.007-2 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 99.9 | 0.0 | |

| C. parapsilosis | Fluconazole | 1,542 | 0.12->128 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 96.2 | 0.6 |

| Voriconazole | 1,541 | 0.007-8 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 99.6 | 0.1 | |

| Posaconazole | 1,542 | 0.007-1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| C. glabrata | Fluconazole | 1,517 | 0.25->128 | 8.0 | 32 | 53.1 | 9.6 |

| Voriconazole | 1,516 | 0.007-8 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 91.1 | 5.7 | |

| Posaconazole | 1,517 | 0.03->8 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 79.6 | 8.3 | |

| C. tropicalis | Fluconazole | 1,198 | 0.12-128 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 99.2 | 0.2 |

| Voriconazole | 1,197 | 0.007-8 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 99.8 | <0.1 | |

| Posaconazole | 1,198 | 0.015-2 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 99.9 | 0.0 | |

| C. krusei | Fluconazole | 305 | 8->128 | 32 | 64 | 1.3 | 34.1 |

| Voriconazole | 305 | 0.07-4 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 99.7 | 0.3 | |

| Posaconazole | 305 | 0.03-4 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 99.0 | 0.3 | |

| C. guilliermondii | Fluconazole | 138 | 0.5-32 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 92.8 | 0.0 |

| Voriconazole | 138 | 0.015-2 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 99.3 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 138 | 0.015-2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 97.1 | 0.0 | |

| C. lusitaniae | Fluconazole | 133 | 0.12-64 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 97.7 | 1.5 |

| Voriconazole | 133 | 0.007-1 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 133 | 0.015-1 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| C. kefyr | Fluconazole | 51 | 0.12-1 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 100 | 0 |

| Voriconazole | 51 | 0.007-0.06 | 0.007 | 0.015 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 51 | 0.015-0.5 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| C. pelliculosa | Fluconazole | 31 | 1-8 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| Voriconazole | 31 | 0.03-0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 31 | 0.25-4 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 58.1 | 6.5 | |

| C. famata | Fluconazole | 19 | 0.5-16 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 94.7 | 0.0 |

| Voriconazole | 19 | 0.007-1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 19 | 0.03-2 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 94.7 | 0.0 | |

| C. rugosa | Fluconazole | 13 | 0.5-16 | 4.0 | 16 | 61.5 | 0.0 |

| Voriconazole | 13 | 0.015-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 13 | 0.03-0.5 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| C. dubliniensis | Fluconazole | 12 | 0.12-8 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.0 |

| Voriconazole | 12 | 0.007-0.03 | 0.007 | 0.03 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 12 | 0.015-0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| C. lipolytica | Fluconazole | 12 | 1-64 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 91.7 | 8.3 |

| Voriconazole | 12 | 0.015-1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 100 | 0.0 | |

| Posaconazole | 12 | 0.12-4 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 91.7 | 8.3 | |

| C. zeylanoides | Fluconazole | 8 | 0.12->128 | 0.5 | 87.5 | 12.5 | |

| Voriconazole | 8 | 0.007-4 | 0.007 | 87.5 | 12.5 | ||

| Posaconazole | 8 | 0.007-2 | 0.06 | 87.5 | 0.0 | ||

| All Candida | Fluconazole | 10,807 | 012->128 | 0.25 | 16 | 89.5 | 2.5 |

| Voriconazole | 10,803 | 0.007-8 | 0.015 | 0.25 | 98.6 | 0.9 | |

| Posaconazole | 10,807 | 0.007->8 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 96.9 | 1.2 | |

The extent of cross-resistance between fluconazole and posaconazole may be seen more clearly in Table 2 and Fig. 1. As was seen previously in comparisons of fluconazole and ravuconazole (30) and fluconazole and voriconazole (35), there was a strong positive correlation (r = 0.88) between posaconazole and fluconazole (Fig. 1). More than 99% (99.5%) of the fluconazole-susceptible isolates were susceptible to posaconazole, as were 83.2% of the fluconazole-SDD isolates (Table 2). Among 272 fluconazole-resistant isolates, 127 (46.7%) were susceptible, 41 (15.1%) were SDD, and 104 (38.2%) were resistant to posaconazole.

TABLE 2.

In vitro activity of posaconazole against 10,807 clinical isolates of Candida species stratified by fluconazole susceptibility category

| Species | Fluconazole susceptibility category (no. of isolates tested) | No. for which posaconazole MIC (μg/ml) was:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | >8 | ||

| C. albicans | S (5,789) | 247 | 2,987 | 1,862 | 620 | 54 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SDD (30) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 6 | |||||||

| R (8) | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| C. parapsilosis | S (1,483) | 1 | 30 | 201 | 625 | 544 | 54 | 27 | 1 | ||||

| SDD (49) | 2 | 14 | 23 | 9 | 1 | ||||||||

| R (10) | 1 | 6 | 3 | ||||||||||

| C. glabrata | S (805) | 3 | 12 | 45 | 173 | 381 | 166 | 24 | 1 | ||||

| SDD (567) | 1 | 9 | 94 | 318 | 122 | 22 | 1 | ||||||

| R (145) | 1 | 4 | 38 | 17 | 13 | 72 | |||||||

| C. tropicalis | S (1,188) | 118 | 315 | 459 | 237 | 55 | 4 | ||||||

| SDD (8) | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| R (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| C. krusei | S (5) | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| SDD (197) | 25 | 113 | 54 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| R (103) | 1 | 1 | 22 | 55 | 22 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| C. guilliermondii | S (128) | 1 | 4 | 5 | 38 | 58 | 15 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| SDD (10) | 4 | 6 | |||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. lusitaniae | S (130) | 16 | 51 | 46 | 12 | 4 | 1 | ||||||

| SDD (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| R (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| C. kefyr | S (51) | 2 | 10 | 14 | 19 | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. pelliculosa | S (31) | 4 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 2 | |||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. famata | S (18) | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| SDD (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. rugosa | S (8) | 3 | 5 | ||||||||||

| SDD (5) | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. dubliniensis | S (12) | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | ||||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. lipolytica | S (11) | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | ||||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| C. zeylanoides | S (7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| All Candida | S (9,667) | 249 | 3,159 | 2,455 | 1,794 | 958 | 376 | 444 | 188 | 41 | 3 | ||

| SDD (868) | 1 | 4 | 46 | 164 | 175 | 332 | 123 | 22 | 1 | ||||

| R (272) | 1 | 5 | 33 | 61 | 27 | 41 | 19 | 13 | 72 | ||||

It should be noted that none of the fluconazole-resistant isolates of C. albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis were resistant to posaconazole, whereas 102 (70%) of the fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata isolates were also resistant to posaconazole (Table 2). This is consistent with the predominant resistance mechanisms seen with these species. Posaconazole is known to bind more extensively to the target enzyme, 14α-demethylase, of C. albicans than does fluconazole, due in part to the presence of a long hydrophobic side chain that serves to stabilize the binding of posaconazole to the target, making it less susceptible to the effect of point mutations in the ERG11 gene (3, 50). Indeed, Li et al. (17) demonstrated that isolates of C. albicans, from a patient with OPC, that were resistant to fluconazole and voriconazole but susceptible to posaconazole all had the same five missense mutations in ERG11 that specifically reduced the binding of fluconazole and voriconazole to the target enzyme. Furthermore, subsequent isolates obtained during the course of posaconazole therapy had all acquired an additional mutation, leading to the disruption of the binding of the posaconazole side chain within the hydrophobic channel of the enzyme (17). Thus, in order for C. albicans to exhibit resistance to posaconazole, there is a requirement for mutational events affecting the target enzyme that are over and above those necessary to produce resistance to fluconazole and voriconazole.

In contrast, the primary mechanism of resistance to azoles in C. glabrata involves upregulation of the genes encoding the CDR efflux pumps (2, 43). All of the azoles, including posaconazole, serve as substrates for the CDR pumps (42), and as a result, cross-resistance to all azoles is a common feature in fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata isolates (43).

The CLSI does not recommend that laboratories test C. krusei against fluconazole, given its poor clinical response to this agent and the fact that the “intrinsic” resistance manifested by this species may be underrepresented by the in vitro results (12, 20, 30-32, 35, 40). In contrast, posaconazole appears quite active against C. krusei (302 [99%] of 305 isolates were susceptible at an MIC of ≤1 μg/ml [Tables 1 and 2]). It is likely that, as with voriconazole (12), posaconazole binds much more tightly to the target enzyme of C. krusei than does fluconazole. As noted previously for both ravuconazole (30) and voriconazole (35), it appears that susceptibility of C. krusei to posaconazole is predictable and testing of this drug-organism combination may not be necessary. When the C. krusei results are removed from the total, we again find that 99.5% of the fluconazole-susceptible isolates and 78.4% of the fluconazole-SDD isolates are susceptible to posaconazole but that only 15% of the fluconazole-resistant isolates are susceptible to posaconazole (data not shown).

When the fluconazole test result category (S, SDD, or R) was used to predict the posaconazole category, the absolute categorical agreement between test results was 91.1%, with 0.1% VME (false-susceptible error), 1.2% ME (false-resistant error), and a 7.6% M rate (Table 3). Given the fact that the fluconazole results clearly do not predict the susceptibility of C. krusei to posaconazole (Tables 1 and 2), we have omitted these results from the analysis, with a resulting improvement in categorical agreement (93.7%) and a decrease in both ME (0.2%) and M (6.0%) (Table 3). These results are virtually the same as those reported previously using fluconazole results to predict the susceptibility of Candida spp. to ravuconazole (30) and to voriconazole (35).

TABLE 3.

Absolute categorical agreement and error rates when the fluconazole result was used to predict the posaconazole susceptibility of Candida spp.

| Species | No. of isolates tested | % Agreement | % VME | % ME | % M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Candida | 10,807 | 91.1 (93.7)a | 0.1 (0.1)a | 1.2 (0.2)a | 7.6 (6.0)a |

| C. albicans | 5,827 | 99.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| C. parapsilosis | 1,542 | 96.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 3.2 |

| C. glabrata | 1,517 | 66.2 (86.0)b | 0.1 (1.6)b | 0.3 (0.3)b | 33.4 (12.1)b |

| C. tropicalis | 1,198 | 99.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| C. krusei | 305 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 33.1 | 64.6 |

| C. guilliermondii | 138 | 89.9 (97.1)b | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.1 (2.9)b |

| C. lusitaniae | 133 | 97.7 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.8 |

| C. kefyr | 51 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. pelliculosa | 31 | 58.1 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 35.5 |

| C. famata | 19 | 89.5 (94.7)b | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.5 (5.3)b |

| C. rugosa | 13 | 61.5 (100)b | 0.0 | 0.0 | 38.5 (0.0)b |

| C. dubliniensis | 12 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. lipolytica | 12 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. zeylanoides | 8 | 87.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 |

The value in parentheses is based on the results for all of the Candida species minus C. krusei (10,502 isolates).

The value in parenthesis was obtained by using the following categories for fluconazole: susceptible, MIC of ≤32 μg/ml (S and SDD combined); resistant, MIC of ≥64 μg/ml.

An absolute categorical agreement of 90% or better (range, 96.2 to 100%) was observed for all of the species tested, except C. glabrata (66.2%), C. krusei (2.3%), C. guilliermondii (89.9%), C. pelliculosa (58.1%), C. famata (89.5%), C. rugosa (61.5%), and C. zeylanoides (87.5%).

As seen with C. krusei, the fluconazole results also underestimate the activity of posaconazole against C. glabrata, C. guilliermondii, C. famata, and C. rugosa (Tables 2 and 3). Between 94 and 100% of the fluconazole-susceptible isolates of these four species were also susceptible to posaconazole (Table 2). Likewise, 74% of the C. glabrata isolates and all of the C. guilliermondii, C. famata, and C. rugosa isolates that were SDD to fluconazole were susceptible to posaconazole. As was done in previous studies with ravuconazole (30) and voriconazole (35), it is possible to improve the ability of the fluconazole MIC test to predict the susceptibility of C. glabrata, C. guilliermondii, C. famata, and C. rugosa to posaconazole by combining the fluconazole S and SDD categories and using fluconazole MICs of ≤32 μg/ml to identify posaconazole-susceptible isolates and MICs of ≥64 μg/ml to identify posaconazole resistance. Using this criterion, the categorical agreement for C. glabrata improves to 86.0%, with 1.6% VME, 0.3% ME, and 12.1% M. Similarly, the categorical agreements for C. famata, C. guilliermondii, and C. rugosa improve to 94.7%, 97.1%, and 100%, respectively. Applying this modified criterion to the entire collection of isolates (minus C. krusei) results in an overall categorical agreement of 97.6%, with 0.2% VME and 0.2% ME.

A similar approach can be taken to assess the extent of cross-resistance between voriconazole and posaconazole and to determine the ability of voriconazole to act as a surrogate marker for the susceptibility of Candida spp. to posaconazole. Similar to that seen in the comparison of fluconazole and posaconazole, there was a strong positive correlation (r = 0.89) between posaconazole and voriconazole MICs (Fig. 2). Overall, the essential agreement (MIC ± 2 dilutions) was 88% (MIC ± 1 dilution was 58%) (Fig. 2), indicating the comparable potencies of these extended-spectrum triazoles against a large collection of Candida isolates. As seen with fluconazole, 98% of the voriconazole-susceptible isolates were susceptible to posaconazole. Among 55 voriconazole-SDD isolates, 8 (14%) were susceptible, 24 (44%) were SDD, and 23 (42%) were resistant to posaconazole. Likewise, among 92 voriconazole-resistant isolates (86 of which were C. glabrata), 4 (4.3%) were susceptible, 11 (12%) were SDD, and 77 (83.7%) were resistant to posaconazole. Thus, 98% of the voriconazole-susceptible and 92% of the voriconazole-nonsusceptible (SDD plus R) isolates were susceptible and nonsusceptible, respectively, to posaconazole. It is notable that the only voriconazole-nonsusceptible isolates that were resistant to posaconazole were isolates of C. glabrata: 48% of voriconazole-SDD isolates and 89.5% of voriconazole-resistant isolates of C. glabrata were resistant (MIC, ≥4 μg/ml) to posaconazole (Table 4). Importantly, none of the voriconazole-resistant isolates of C. glabrata were susceptible (MIC ≤1 μg/ml) to posaconazole. These findings are consistent with the known mechanism of azole resistance among isolates of C. glabrata.

TABLE 4.

In vitro activity of posaconazole against 10,803 clinical isolates of Candida species stratified by voriconazole susceptibility category

| Species | Voriconazole susceptibility category (no. of isolates tested) | No. for which posaconazole MIC (μg/ml) was:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | >8 | ||

| C. albicans | S (5,824) | 247 | 2,988 | 1,861 | 621 | 57 | 26 | 15 | 8 | 1 | |||

| SDD (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| R (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| C. parapsilosis | S (1,535) | 1 | 29 | 201 | 627 | 558 | 81 | 36 | 2 | ||||

| SDD (4) | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| R (2) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| C. glabrata | S (1,382) | 3 | 13 | 45 | 183 | 475 | 487 | 151 | 21 | 4 | |||

| SDD (48) | 1 | 24 | 10 | 3 | 10 | ||||||||

| R (86) | 9 | 9 | 6 | 62 | |||||||||

| C. tropicalis | S (1,195) | 118 | 314 | 459 | 240 | 57 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| SDD (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| R (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| C. krusei | S (304) | 1 | 1 | 26 | 137 | 108 | 28 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| C. guilliermondii | S (137) | 1 | 4 | 5 | 38 | 62 | 20 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| SDD (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. lusitaniae | S (133) | 16 | 51 | 46 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. kefyr | S (51) | 2 | 10 | 14 | 19 | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. pelliculosa | S (31) | 4 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 2 | |||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. famata | S (19) | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. rugosa | S (13) | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. dubliniensis | S (12) | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | ||||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. lipolytica | S (12) | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (0) | |||||||||||||

| C. zeylanoides | S (7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| SDD (0) | |||||||||||||

| R (1) | 1 | ||||||||||||

| All Candida | S (10,656) | 249 | 3,159 | 2,454 | 1,798 | 1,007 | 570 | 674 | 546 | 170 | 25 | 4 | |

| SDD (55) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 24 | 10 | 3 | 10 | |||||

| R (92) | 1 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 6 | 62 | |||||||

When the voriconazole test result category (S, SDD, or R) was used to predict the posaconazole category, the absolute categorical agreement between test results was 97.7%, with 0.3% VME, 0.1% ME, and 1.9% M rates (Table 5). Among the 14 species of Candida tested, the categorical agreement was 90% or better (range, 91.7% to 100%) for all species except C. glabrata (86.2%), C. pelliculosa (58%), and C. zeylanoides (87.5%). For the most part, the discrepancies in category results involving these species were minor errors, although unacceptably high VME rates were seen with C. pelliculosa (6.5%) and C. lipolytica (8.3%). Aside from these two uncommon species, voriconazole accurately predicted susceptibility and resistance to posaconazole among Candida spp.

TABLE 5.

Absolute categorical agreement and error rates when the voriconazole result was used to predict the posaconazole susceptibility of Candida spp.

| Species | No. of isolates tested | % Agreement | % VME | % ME | % M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Candida | 10,803 | 97.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| C. albicans | 5,826 | 99.9 | 0.0 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| C. parapsilosis | 1,541 | 99.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| C. glabrata | 1,516 | 86.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 12.1 |

| C. tropicalis | 1,197 | 99.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| C. krusei | 305 | 98.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| C. guilliermondii | 138 | 96.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 |

| C. lusitaniae | 133 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. kefyr | 51 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. pelliculosa | 31 | 58.0 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 35.5 |

| C. famata | 19 | 94.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| C. rugosa | 13 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. lipolytica | 12 | 91.7 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. dubliniensis | 12 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C. zeylanoides | 8 | 87.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 |

The results of this study clearly demonstrate the extent of cross-resistance among posaconazole, fluconazole, and voriconazole. Although rare, isolates of C. albicans that are resistant to either fluconazole or voriconazole may be susceptible to posaconazole, depending on the number and locations of target enzyme mutations and the expression of CDR efflux pumps. The latter resistance mechanism, however, ensures virtually complete cross-resistance among the triazoles with isolates of C. glabrata. Only 3% of the fluconazole-resistant isolates and none of the voriconazole-resistant isolates of C. glabrata were susceptible to posaconazole. Conversely, there is no cross-resistance between fluconazole and either posaconazole or voriconazole among isolates of C. krusei, a species that is predictably susceptible to these two extended-spectrum triazoles.

The strategy of using class representatives or surrogate markers to predict susceptibility or resistance to other agents in the same class has been used for decades in antibacterial susceptibility testing to develop practical alternatives for the microbiology laboratory when specific diagnostic susceptibility testing reagents are limited or unavailable (4, 15, 16, 21-23). Given the lack of FDA-approved testing systems and CLSI/FDA breakpoints for posaconazole, the approach described in the present study provides a useful strategy for laboratories in the effort to optimize antifungal therapy of candidal infections.

As was shown previously for ravuconazole (30) and for voriconazole (35), fluconazole functioned well as a surrogate marker for posaconazole when applied to this collection of clinically significant isolates of Candida spp. The absolute categorical agreement of 91.1% (93.7% without C. krusei), with only 0.1% VME among the more than 10,000 isolates tested, easily meets the recognized criteria for a reliable surrogate marker as applied to antibacterial susceptibility testing (16). The use of fluconazole as a surrogate marker for posaconazole susceptibility was improved by designating those isolates for which the fluconazole MICs were ≤32 μg/ml (S and SDD categories combined) as susceptible to posaconazole, with the resistant category staying the same at ≥64 μg/ml. The resulting 97.6% categorical agreement and 0.2% VME rate are excellent for a surrogate marker test. Likewise, voriconazole was shown to perform well as a surrogate marker for posaconazole susceptibility and resistance, with a categorical agreement of 97.7% and a 0.3% VME rate. Thus, either fluconazole or voriconazole can be used effectively as a surrogate marker for posaconazole. The somewhat greater availability of fluconazole as a test reagent on commercial MIC panels (34, 38), and the ability of fluconazole to serve as a surrogate marker for both posaconazole and voriconazole (35), may make this agent a more convenient and useful tool than voriconazole for microbiology laboratories.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the existence of cross-resistance among fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole with the greatest emphasis on C. glabrata. Furthermore, we have shown that the availability of posaconazole susceptibility testing results for Candida spp., in any medical center currently performing antifungal susceptibility testing of either fluconazole or voriconazole, can be accomplished by using the fluconazole or voriconazole result as a surrogate marker for posaconazole susceptibility and resistance. Arguably, the most important role of in vitro susceptibility testing is to predict the resistance of the infecting organism to the agent under consideration for use in the patient (32, 33, 37). The occurrence of false-resistance errors with this application of the “class representative” concept to the available triazoles was very low and was acceptable for surrogate marker testing. Notably, only 15% of the fluconazole-resistant isolates (minus C. krusei) and 4% of the voriconazole-resistant isolates were susceptible to posaconazole at an MIC of ≤1 μg/ml. As commercial FDA-approved posaconazole susceptibility products become available, they should replace the interim use of surrogate markers for clinical testing. Until that time, microbiology laboratories may find it most convenient to use fluconazole as the surrogate marker for both voriconazole and posaconazole.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by unrestricted research grants from Pfizer Inc. and Schering-Plough.

Linda Elliott and Tara Schroder provided excellent support in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 December 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anstead, G. M., G. Corcoran, J. Lewis, D. Berg, and J. R. Graybill. 2005. Refractory coccidioidomycosis treated with posaconazole. Clin. Infect. Dis. 401770-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borst, A., M. T. Raimer, D. W. Warnock, C. J. Marrison, and B. A. Arthington-Skaggs. 2005. Rapid acquisition of stable azole resistance by Candida glabrata isolates obtained before the clinical introduction of fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49783-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chau, A. S., C. A. Mendrick, F. J. Sabatelli, D. Loebenberg, and P. M. Nichols. 2004. Application of real-time quantitative PCR to molecular analysis of Candida albicans strains exhibiting reduced susceptibility to azoles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 482124-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Development of in vitro susceptibility testing criteria and quality control parameters; approved guideline—third edition. CLSI document M23-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 5.Cornely, O. A., J. Maertens, D. J. Winston, J. Perfect, A. J. Ullman, T. J. Walsh, D. Helfgott, J. Holowiecki, D. Stockelberg, Y. T. Goh, M. Petrini, C. Hardalo, R. Suresh, and D. Angulo-Gonzalez. 2007. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 356348-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuenca-Estrella, M., A. Gomez-Lopez, E. Mellado, M. J. Buitrago, A. Monzan, and J. L. Rodriguez-Tudela. 2006. Head-to-head comparison of the activities of currently available antifungal agents against 3,378 Spanish clinical isolates of yeasts and filamentous fungi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50917-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diekema, D. J., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and M. A. Pfaller. 2003. Activities of caspofungin, itraconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against 448 recent clinical isolates of filamentous fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413623-3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diekema, D. J., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, L. B. Boyken, S. Tendolkar, J. Kroeger, and M. A. Pfaller. 2007. Evaluation of Etest and disk diffusion methods compared with broth microdilution antifungal susceptibility testing of clinical isolates of Candida spp. against posaconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451974-1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 2003. In vitro antifungal activities of anidulafungin and micafungin, licensed agents and the investigational triazole posaconazole as determined by NCCLS methods for 12,062 fungal isolates: review of the literature. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 20121-136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinel-Ingroff, A., M. Pfaller, S. A. Messer, C. C. Knapp, N. Holliday, and S. B. Killian. 2004. Multicenter comparison of the Sensititre YeastOne Colorimetric Antifungal Panel with NCCLS M27-A2 reference method for testing new antifungal agents against clinical isolates of Candida spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42718-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferraro, M. J., and J. H. Jorgenson. 1995. Instrument-based antibacterial susceptibility testing, p. 1379-1384. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 6th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 12.Fukuoka, T., D. A. Johnston, C. A. Winslow, M. J. deGroot, C. Burt, C. A. Hitchcock, and S. G. Filler. 2003. Genetic basis for differential activities of fluconazole and voriconazole against Candida krusei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 471213-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González, G. M., A. W. Fothergill, D. A. Sutton, M. G. Rinaldi, and D. Loebenberg. 2005. In vitro activities of new and established triazoles against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi. Med. Mycol. 43281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazen, K. C., and S. A. Howell. 2007. Candida, Cryptococcus, and other yeasts of medical importance, p. 1762-1788. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgenson, M. L. Landry, and M. A. Pfaller (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 9th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 15.Jones, R. N., M. A. Pfaller, and the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program Participants Group (USA). 2001. Can antimicrobial susceptibility testing results for ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin predict susceptibility to a newer fluoroquinolone, gatifloxacin? Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997-99). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones, R. N., H. S. Sader, T. R. Fritsche, P. A. Hogan, and D. J. Sheehan. 2006. Selection of a surrogate agent (vancomycin or teicoplanin) for initial susceptibility testing of dalbavancin: results from an international antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442622-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, X., N. Broun, A. S. Chau, J. L. Lopez-Ribot, M. T. Ruesga, G. Quindos, C. A. Mendrick, R. S. Hare, D. Loebenberg, B. DiDomenico, and P. M. McNicholas. 2004. Changes in susceptibility to posaconazole in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 5374-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lortholary, O., E. Dannaoui, D. Raoux, D. Hoinard, A. Datry, A. Paugam, J. L. Poirot, C. Lacroix, F. Dromer, and the YEASTS Group. 2007. In vitro susceptibility to posaconazole of 1,903 yeast isolates recovered in France from 2003 to 2006 and tested by the method of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 513378-3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morace, G., G. Amato, F. Bistoni, G. Fadda, P. Marone, M. T. Montagna, S. Oliveri, L. Polonelli, R. Rigoli, I. Mancuso, S. La Face, L. Masucci, L. Romano, C. Napoli, D. Tatò, M. G. Buscema, C. M. C. Belli, M. M. Piccirillo, S. Conti, S. Covan, F. Fanti, C. Cavanna, F. D'Alò, and L. Pitzurra. 2002. Multicenter comparative evaluation of six commercial systems and the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards M27-A broth microdilution method for fluconazole susceptibility testing of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402953-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard, 2nd ed., M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; approved standard, 8th ed., M2-A8. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 6th ed., M7-A6. National Committee for Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 13th informational supplement, M100-S13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 24.Ostrosky-Zeichner, L., J. H. Rex, P. G. Pappas, R. J. Hamill, R. A. Larsen, H. W. Horowitz, W. G. Powderly, N. Hyslop, C. A. Kauffman, J. Cleary, J. E. Mangino, and J. Lee. 2003. Antifungal susceptibility survey of 2,000 bloodstream Candida isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 473149-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, and R. N. Jones. 2001. In vitro activities of posaconazole (Sch 56592) compared with those of itraconazole and fluconazole against 3,685 clinical isolates of Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 452862-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and D. J. Diekema. 2002. In vitro susceptibilities of ravuconazole and voriconazole compared with those of four approved systemic antifungal agents against 6,970 clinical isolates of Candida spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 461723-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, R. N. Jones, S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, and the SENTRY Participants Group. 2002. Trends in antifungal susceptibility of Candida spp. isolated from pediatric and adult patients with bloodstream infections: SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997 to 2000. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40852-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, C. Rice, S. Tendolkar, and D. J. Diekema. 2004. In vitro activities of voriconazole, posaconazole, and fluconazole against 4,169 clinical isolates of Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans collected during 2001 and 2002 in the ARTEMIS global antifungal surveillance program. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 48201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaller, M. A., A. Espinel-Ingroff, and R. N. Jones. 2004. Clinical evaluation of the Sensititre YeastOne Colorimetric Antifungal Plate for antifungal susceptibility testing of the new triazoles voriconazole, posaconazole, and ravuconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 424577-4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, C. Rice, S. Tendolkar, R. J. Hollis, and D. J. Diekema. 2004. Cross-resistance between fluconazole and ravuconazole and the use of fluconazole as a surrogate marker to predict susceptibility and resistance to ravuconazole among 12,796 clinical isolates of Candida spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 423137-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2004. 12 years of fluconazole in clinical practice: global trends in species distribution and fluconazole susceptibility of Candida bloodstream isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10(Suppl. 1)11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, and D. J. Sheehan. 2006. Interpretive breakpoints for fluconazole and Candida revisited: a blueprint for the future of antifungal susceptibility testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19435-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, J. H. Rex, A. Espinel-Ingroff, E. M. Johnson, D. Andes, V. Chaturvedi, M. A. Ghannoum, F. C. Odds, M. G. Rinaldi, D. J. Sheehan, P. Troke, T. J. Walsh, and D. W. Warnock. 2006. Correlation of MIC with outcome for Candida species testing against voriconazole: analysis and proposal for interpretive breakpoints. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44819-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfaller, M. A., and R. N. Jones for the Microbiology Resource Committee of the College of American Pathologists. 2006. Performance accuracy of antibacterial and antifungal susceptibility test methods: report from the College of American Pathologists (CAP) Microbiology Surveys Program (2001-2003). Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 130767-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, C. Rice, S. Tendolkar, R. J. Hollis, and D. J. Diekema. 2007. Use of fluconazole as a surrogate marker to predict susceptibility and resistance to voriconazole among 13,338 clinical isolates of Candida spp. tested by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute-recommended broth microdilution methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 4570-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2007. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20133-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2007. Azole antifungal drug cross-resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and clinical significance. J. Invasive Fungal Infect. 174-92. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, G. W. Procop, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2007. Multicenter comparison of VITEK 2 Yeast Susceptibility Test with the CLSI broth microdilution reference method for testing fluconazole against Candida spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45796-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raad, I. I., R. Y. Hachem, R. Herbrecht, J. R. Graybill, R. Hare, G. Corcoran, and D. P. Kontoyiannis. 2006. Posaconazole as salvage treatment for invasive fusariosis in patients with underlying hematologic malignancy and other conditions. Clin. Infect. Dis. 421389-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rex, J. H., M. A. Pfaller, J. N. Galgiani, M. S. Bartlett, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, M. Lancaster, F. C. Odds, M. G. Rinaldi, T. J. Walsh, and A. L. Barry. 1997. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabatelli, F., R. Patel, P. A. Mann, C. A. Mendrick, C. C. Norris, R. Hare, D. Loebenberg, T. A. Black, and P. M. McNicholas. 2006. In vitro activities of posaconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against a large collection of clinically important molds and yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 502009-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, D. Calabrese, P. A. Majcherczyk, and J. Bille. 1999. The ATP binding cassette transplant gene CgCDR1 from Candida glabrata is involved in the resistance of clinical isolates to azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 432753-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanguinetti, M., B. Posteraro, B. Fiori, S. Ranno, R. Torelli, and G. Fadda. 2005. Mechanisms of azole resistance in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata collected during a hospital survey of antifungal resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49668-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sims, C. R., V. L. Paetznick, J. R. Rodriguez, J. R. Rodriguez, E. Chen, and L. Ostrosky-Zeichner. 2006. Correlation between microdilution, Etest, and disk diffusion methods for antifungal susceptibility testing of posaconazole against Candida spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442105-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skiest, D. J., J. A. Vazquez, G. M. Anstead, J. R. Graybill, J. Reynes, D. Ward, R. Hare, N. Boparai, and R. Isaacs. 2007. Posaconazole for the treatment of azole-refractory oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in subjects with HIV infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44607-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ullmann, A. J., O. A. Cornely, A. Burchardt, R. Hachem, D. P. Kontoyiannis, K. Topelt, R. Courtney, D. Wexler, G. Krishna, M. Martinho, G. Corcoran, and I. Raad. 2006. Pharmacokinetics safety, and efficacy of posaconazole in patients with persistent febrile neutropenia or with refractory invasive fungal infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50658-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ullmann, A. J., J. H. Lipton, D. H. Vesole, P. Chandrasekar, A. Longston, S. R. Tarantolo, H. Greinix, W. M. deAzevedo, V. Reddy, N. Boparai, L. Pedicane, H. Patino, and S. Durrant. 2007. Posaconazole or fluconazole for prophylaxis in severe graft-versus-host disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 356335-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vazquez, J. A., D. J. Skeist, L. Nieto, R. Northland, I. Sanne, J. Gogate, W. Greaves, and R. Isaacs. 2006. A multicenter randomized trial evaluating posaconazole versus fluconazole for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in subjects with HIV/AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 421179-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh, T. J., I. Raad, T. F. Patterson, P. Chandrasekar, G. R. Donowitz, R. Graybill, R. E. Greene, R. Hachem, S. Hadley, R. Herbrecht, A. Langston, A. Louie, P. Ribaud, B. H. Segal, D. A. Stevens, J. A. van Burik, C. S. White, G. Corcoran, J. Gogate, G. Krishna, L. Pedicone, C. Hardalo, and J. R. Perfect. 2007. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of conventional therapy: an externally controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 442-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao, L., V. Madison, A. S. Chau, D. Loebenberg, R. E. Palermo, and P. M. McNicholas. 2004. Three-dimensional models of wild-type and mutated forms of cytochrome P450 14α-sterol demethylases from Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans provide insights into posaconazole binding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48568-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]