Abstract

The pathogenic yeast Candida dubliniensis is phylogenetically very closely related to Candida albicans, and both species share many phenotypic and genetic characteristics. DNA fingerprinting using the species-specific probe Cd25 and sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal gene cluster previously showed that C. dubliniensis is comprised of three major clades comprising four distinct ITS genotypes. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has been shown to be very useful for investigating the epidemiology and population biology of C. albicans and has identified many distinct major and minor clades. In the present study, we used MLST to investigate the population structure of C. dubliniensis for the first time. Combinations of 10 loci previously tested for MLST analysis of C. albicans were assessed for their discriminatory ability with 50 epidemiologically unrelated C. dubliniensis isolates from diverse geographic locations, including representative isolates from the previously identified three Cd25-defined major clades and the four ITS genotypes. Dendrograms created by using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages that were generated using the data from all 10 loci revealed a population structure which supports that previously suggested by DNA fingerprinting and ITS genotyping. The MLST data revealed significantly less divergence within the C. dubliniensis population examined than within the C. albicans population. These findings show that MLST can be used as an informative alternative strategy for investigating the population structure of C. dubliniensis. On the basis of the highest number of genotypes per variable base, we recommend the following eight loci for MLST analysis of C. dubliniensis: CdAAT1b, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdMPIb, CdRPN2, CdSYA1, exCdVPS13, and exCdZWF1b, where “Cd” indicates C. dubliniensis and “ex” indicates extended sequence.

Candida dubliniensis is a pathogenic yeast species that is phenotypically, genetically, and phylogenetically very closely related to Candida albicans, the yeast species most commonly associated with infection in humans (49, 51). Despite their close relationship, C. albicans is significantly more pathogenic (49, 50). C. dubliniensis is most commonly associated with oral carriage and infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and diabetic patients, although it has been identified as a minor constituent of the commensal floras in the oral cavities of healthy individuals (40, 49, 50). Although C. dubliniensis has also been recovered from patients with systemic infections, its incidence is far lower than that of C. albicans. While the latter is responsible for 40 to 60% of cases of candidemia, C. dubliniensis has been identified in only 1 to 2% of blood culture yeast samples (11, 15, 27, 29-31). These epidemiological data are reflected in the results of animal infection model studies that demonstrated that C. albicans is significantly more pathogenic than C. dubliniensis (22, 47, 56). The reasons for the lower virulence of C. dubliniensis relative to that of C. albicans have not been investigated in detail; however, recently published data showed that C. dubliniensis has a reduced capacity to produce hyphae that results in lower levels of colonization and tissue invasion (47).

In order to be able to perform meaningful and informative epidemiological studies of Candida isolates, it is essential to be able to discriminate between unrelated strains of the species of interest. Ideally, strain differentiation methods should be highly discriminatory, reproducible, and suitable for the analysis of large numbers of isolates. To date, DNA fingerprinting using the species-specific, semirepetitive-sequence-containing DNA probe Cd25 has been the most widely applied and informative tool used for C. dubliniensis epidemiology and population analysis. When first developed, data generated using this probe showed that C. dubliniensis is comprised of two distinctive major clades, termed Cd25 fingerprint groups I and II (21, 26). Cd25 group I isolates are all closely related, with an average similarity coefficient (SAB) value of approximately 0.8 (range, 0.8 to 0.86), where A and B represent two different strains. These isolates comprise the majority of isolates investigated to date recovered in many countries around the world, mainly from HIV-infected individuals (4, 21, 26). Furthermore, sequence analysis of the internally transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rRNA gene cluster revealed that Cd25 group I isolates consist of a single ITS genotype: ITS genotype 1 (21). In contrast, Cd25 group II isolates are more diverse, with an average SAB value of 0.52 (range, 0.07 to 0.67) (4), and consist of three separate ITS genotypes (ITS genotypes 2 to 4), which correspond to distinct subclades within the Cd25 group II fingerprinting clade (21). More recently, a third major clade, termed Cd25 group III, was identified among isolates from Egypt and Saudi Arabia and displayed an average SAB value of 0.35 (range, 0.16 to 0.54) (4). The DNA fingerprints of Cd25 group III isolates are very distinctive relative to those of isolates from Cd25 groups I and II, and ITS sequence analysis revealed that they belong to ITS genotypes 3 and 4 (4). All Cd25 group III isolates examined to date exhibit resistance to 5-flucytosine (4).

DNA fingerprinting analysis of large numbers of C. albicans isolates using the species-specific, repetitive-sequence-containing Ca3 probe has demonstrated that the population structure of the species is complex, with five major clades, some of which appear to be associated with specific geographic locations (6, 42, 46). In comparison, the population structure of C. dubliniensis determined with the Cd25 probe is significantly less complex (4, 21, 26). Although DNA fingerprinting has been shown to be a very useful tool in the molecular epidemiological analysis of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis populations, it is time-consuming, expensive, and not conducive to interlaboratory comparisons. There are many other molecular strain-typing techniques that have been applied to the analysis of Candida species (e.g., karyotyping and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting, etc. [45]). However, all of these methodologies also suffer from drawbacks, particularly in relation to reproducibility. In the late 1990s, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), a technique based on the nucleotide sequence analysis of a set of housekeeping genes, was developed for the population analysis of several bacterial species (28). This technique has also been applied to the analysis of the diploid yeast C. albicans (9, 10, 54) and to other Candida species (17, 25, 53). In 2002, Bougnoux et al. identified six housekeeping gene loci that allowed accurate and reproducible discrimination between unrelated C. albicans isolates (9). A study by Tavanti et al. used four of these loci and a further four loci and also showed high levels of discrimination (54). These two groups of researchers subsequently revised the combination of loci used in the MLST analysis of C. albicans, aiming to identify the minimum number of loci required to maintain the high discriminatory standard of the scheme (10). An agreed consensus scheme between the different laboratories examined seven loci, AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b, and allowed the application of MLST to the analysis of C. albicans epidemiology and population structure (7-9, 16, 36, 52). MLST analysis has since been demonstrated to be as sensitive as DNA fingerprinting (43), and due to the nature of the data (i.e., DNA sequences of specific loci), these can be used to create a large database generated by multiple laboratories (7). In the case of C. albicans, it has also been shown that the strain groupings identified by MLST correlate with clades of C. albicans organisms identified using the species-specific DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 (52). When applied to specific epidemiological studies, the use of MLST has identified intrafamilial transmission of C. albicans from the human digestive tract, strain maintenance, replacement, and microevolution (8).

The purpose of the present study was to determine the usefulness of MLST for investigating the epidemiology and population structure of C. dubliniensis. In addition, we hypothesized that if the same set of MLST loci currently used for C. albicans could be applied to the analysis of C. dubliniensis, then comparative sequence data could be used to provide valuable information concerning the evolutionary relatedness of the two species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. dubliniensis isolates.

The 50 epidemiologically unrelated C. dubliniensis isolates used in this study are shown in Table 1. Isolates were selected from diverse geographical locations and included representatives of the three Cd25 major fingerprinting clades and all four ITS genotypes. The majority of the isolates studied have been described previously; however, a number of new clinical isolates were also included (Table 1). These new isolates were initially presumptively identified on the basis of dark-green colony coloration on Candida-selective chromogenic agar (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) and on the basis of hyphal fringe production on Pal's agar after 48 h of growth at 30°C as described by Al Mosaid et al. (3). The identities of presumptive C. dubliniensis isolates were further confirmed using the API ID 32C yeast identification system (bioMérieux, Paris, France) (37). Definitive identification of C. dubliniensis was confirmed by PCR using primers specific for the CdACT1-associated intron as described previously (18).

TABLE 1.

C. dubliniensis isolates investigated by MLST analysisc

| Isolate | Country of origin | Yr of isolation | Underlying patient condition | Sample | MLST cladea | ITS genotype | Cd25 fingerprint group | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD36b | Ireland | 1988 | HIV pos | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 21, 51 |

| CD06033b | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD06031 | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD060213 | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD06041 | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD06038b | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD06045 | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD06037b | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 2 | 2 | ND | This study |

| CD06036b | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 2 | 2 | ND | This study |

| CD060215b | Ireland | 2006 | CF | Sputum | 3 | 3 | ND | This study |

| CD604b | France | 2000 | HIV asymptomatic | Throat | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CD603b | France | 2000 | HIV asymptomatic | Throat | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| CM1b | Australia | 1991 | HIV pos | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 21, 51 |

| SA105 | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | Diabetes | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 4 |

| SA115 | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | Diabetes | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 4 |

| SA116 | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | Diabetes | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 4 |

| SA108b | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | Diabetes | Oral | 3 | 3 | III | 4 |

| SA100b | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | Leukemia | Oral | 3 | 3 | III | 4 |

| SA121b | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | S/P renal tx | Oral | 3 | 4 | III | 4 |

| Eg202 | Egypt | 2002 | Cancer | Oral | 3 | 4 | III | 4 |

| Eg203 | Egypt | 2002 | Cancer | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 4 |

| Eg204 | Egypt | 2002 | Cancer | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 4 |

| Eg207 | Egypt | 2002 | Diabetes | Oral | 3 | 4 | III | 4 |

| p6785b | Israel | 1999 | HIV neg | Urine | 3 | 3 | II | 4, 39 |

| p7276b | Israel | 1999 | HIV neg | Respiratory tract | 3 | 3 | II | 4 |

| p7718 | Israel | 1999 | HIV neg | Wound | 3 | 4 | III | 4, 21 |

| CD71 | Argentina | 1994 | HIV pos | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 21, 48 |

| CD98923 | India | 1998 | HIV pos | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 2 |

| B1324 | United States | 1998 | NA | Tongue | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| B341 | United States | 1998 | NA | Throat | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| PM6-2 | Chile | 2006 | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | ND | This study |

| P2 | Switzerland | 1993 | HIV pos | Oral | 1 | 1 | I | 4, 21 |

| 1504 | Slovakia | 2005 | NA | Tonsular swab | 1 | 1 | ND | 32 |

| 8882 | Slovakia | 2005 | Congenital hydrocephalus | Tonsular swab | 1 | 1 | ND | 32 |

| 9097 | Slovakia | 2005 | Leukemia | Tonsular swab | 1 | 1 | ND | 32 |

| 966/3(1)b | Slovakia | 2005 | NA | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | 32 |

| 966/3(2) | Slovakia | 2005 | NA | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | 32 |

| CCY29-177-1 | Slovakia | 2005 | Pelvic organ inflammation | Cervical swab | 1 | 1 | ND | 32 |

| MLNIH0479 | Thailand | 2005 | Leukemia | Blood | 1 | 1 | ND | 13 |

| MLNIH0720 | Thailand | 2005 | TB, anemia, diabetes | Oral | 1 | 1 | ND | 13 |

| 49831 | Japan | 2005 | Anemia | Sputum | 2 | 2 | ND | 13 |

| IFM49883 | Japan | 2005 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | ND | 13 |

| IFM0492 | Thailand | 2005 | Cancer | Blood | 1 | 1 | ND | 13 |

| IFM49832 | Japan | 2005 | Diabetes | Sputum | 1 | 1 | ND | 13 |

| Can4 | Canada | 1996 | HIV pos | Oral | 2 | 2 | II | 21, 38 |

| CD539 | United Kingdom | 1994 | AIDS | Oral | 2 | 2 | II | 21, 38 |

| CBS2747 | The Netherlands | 1952 | HIV neg | Sputum | 2 | 2 | II | 21, 31 |

| CD514 | Ireland | 1995 | HIV neg | Oral | 3 | 3 | II | 21 |

| CD519 | Ireland | 1997 | AIDS | Oral | 3 | 3 | II | 21 |

| CD75004 | United Kingdom | 1975 | Diabetes | Oral | 2 | 2 | II | 21, 38 |

MLST clades assigned in the present study.

Isolate included in assessment of sequence stability and MLST reproducibility.

HIV pos, HIV infected; HIV neg, HIV negative; CF, cystic fibrosis; S/P renal tx, stage post-renal transplantation; NA, not available; TB, tuberculosis; ND, not determined.

Isolates were routinely cultured on potato dextrose agar (Oxoid) medium, pH 5.6, at 37°C. Liquid cultures were grown overnight in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose broth at 37°C in an orbital incubator (Gallenkamp, Leicester, United Kingdom) at 200 rpm.

C. albicans isolates.

A selection of 50 C. albicans isolates (Table 2) was chosen to represent a range of the 17 MLST clades recently described by Odds et al. (35). Sequence data for each of the 50 C. albicans isolates were available at http://test1.mlst.net/ for the seven collaborative consensus MLST loci, AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b (35), and at http://calbicans.mlst.net/ for the RPN2 locus (9). All locus sequences were treated in a manner identical to that used for the C. dubliniensis sequence data, as described below.

TABLE 2.

Candida albicans isolates used in the MLST study

| Isolate | MLST cladea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| APRHCRC1 | 4 | 35 |

| APRURC3 | 6 | 35 |

| APRURM3 | 1 | 35 |

| APRURM6 | 9 | 35 |

| APRURM7 | 10 | 35 |

| BCHURC10 | 10 | 35 |

| BCHURC15 | 11 | 35 |

| BCHURS24 | S | 35 |

| BCHURS9 | 4 | 35 |

| CCHHCRM11 | 4 | 35 |

| CCHHCRM4 | 14 | 35 |

| CCHHCRM7 | 9 | 35 |

| CCHURM1 | 15 | 35 |

| CCHURM12 | 9 | 35 |

| CCHURM4 | 11 | 35 |

| CCHURM9 | 16 | 35 |

| CCHURS10 | 9 | 35 |

| CP04 | 1 | 35 |

| CP05 | S | 35 |

| CP06 | 1 | 35 |

| CP08 | 1 | 35 |

| CP12 | 4 | 35 |

| CP15 | 3 | 35 |

| CP54 | 2 | 35 |

| CP58 | 4 | 35 |

| CP85 | 4 | 35 |

| DPC111 | 9 | 8 |

| DPC118 | 1 | 8 |

| DPC168 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC18 | 12 | 8 |

| DPC2 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC206 | 1 | 8 |

| DPC208 | 5 | 8 |

| DPC22 | 12 | 8 |

| DPC25 | 3 | 8 |

| DPC28 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC35 | 17 | 8 |

| DPC37 | 1 | 8 |

| DPC44 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC47 | 3 | 8 |

| DPC5 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC55 | 1 | 8 |

| DPC6 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC65 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC66 | 9 | 8 |

| DPC70 | 11 | 8 |

| DPC81 | 2 | 8 |

| DPC90 | 4 | 8 |

MLST clades correspond to those recently identified by Odds et al. (35). S stands for singletons, i.e., isolates that were not assigned to any of the 17 clades.

Chemicals, enzymes, and oligonucleotides.

Analytical-grade or molecular biology-grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Ireland Ltd. (Tallaght, Dublin, Ireland) or Fisher Scientific Ltd. (Loughborough, United Kingdom). Enzymes were purchased from the Promega Corporation (Madison, WI) or New England Biolabs Inc. (Beverly MA) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions. Custom-synthesized oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma Genosys Biotechnologies Europe Ltd. (Pampisford, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom).

C. dubliniensis DNA isolation.

Isolates were grown overnight in 5 ml of yeast extract-peptone-dextrose broth, and cells from 1.5 ml of culture were harvested by centrifugation. DNA was extracted from the cells as described by Gallagher et al. (20).

Genotyping of C. dubliniensis.

Template DNA was tested in separate PCR amplification experiments with each of the primer pairs G1F/G1R, G2F/G2R, G3F/G3R, and G4F/G4R to identify the ITS genotype of the isolate (21). Genotypes are ascribed based on the nucleotide sequences of the ITS1 and ITS2 regions and of the intervening 5.8S rRNA gene (57). Template DNAs from the four reference C. dubliniensis isolates (CD36, genotype 1; Can4, genotype 2; CD519, genotype 3, and p7718, genotype 4) previously described by Gee et al. (21) were used in control amplification reactions. Each PCR was carried out with one pair of ITS genotype-specific primers and the universal fungal primers RNAF/RNAR (19), which amplify approximately 610 bp from all fungal large-subunit rRNA genes and were used as an internal positive control. Genotyping experiments were performed on a minimum of two occasions, with each isolate being tested with separately prepared C. dubliniensis template DNA.

Selection of loci for MLST analysis.

Due to the high level of sequence homology between the majority of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis open reading frames (33), all loci previously examined for the purpose of MLST analysis in C. albicans were also investigated for their potential use with C. dubliniensis. The usefulness of the six genes in C. albicans examined as described by Bougnoux et al. (9) (i.e., ACC1, VPS13, GLN4, ADP1, RPN2 and SYA1) and the additional four loci described by Tavanti et al. (54) (i.e., AAT1a, AAT1b, MPIb, and ZWF1b) was assessed. The C. albicans MLST locus sequences were used in separate BLAST searches against the C. dubliniensis genome sequence database (the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute C. dubliniensis genome sequence project, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/sequencing/Candida/dubliniensis/). For each MLST locus, sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W sequence alignment computer program (55), and the C. albicans primer binding regions were identified in the alignment. Any nucleotide differences in the primer binding regions between the species were adjusted in the corresponding C. dubliniensis oligonucleotides to facilitate optimum amplification. All of the C. dubliniensis-optimized primer pairs yielded a single PCR product of the expected size (ranging in size from 400 bp to 700 bp) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide primers and sequences used for C. dubliniensis MLST analysis

| Locus | Amplicon size (bp) in C. dubliniensis | No. of bases analyzed in C. dubliniensis (bp)a | Coordinates ofb:

|

Analyzed segment sequence homology (%)c | Primerd | Analyzed segment start (5′) and end (3′) points in C. dubliniensise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans amplicon | C. dubliniensis amplicon | ||||||

| CdAAT1a | 480 | 373 | +31-+508 | +35-+497 | 91 | 5′-ATCAAACTACTAAATTTTTGAC-3′ (forward) | 5′-ATTGAAA |

| 5′-CGGCAACATGATTAGCCC-3′ (reverse) | 3′-CGATTT | ||||||

| CdAAT1b | 491 | 341 | +736-+1,226 | +742-+1,233 | 95 | 5′-ATGGCTTATCAAGGTTTTGC-3′ (forward) | 5′-TTAACTAA |

| 5′-GTAGCATAAACTGAATAATCA-3′ (reverse) | 3′-TTGGGATCA | ||||||

| CdACC1 | 519 | 407 | +3,184-+3,702 | +3,190-+3,708 | 93 | 5′-GCCAGAGAAATTTTGATCCAATGT-3′ (forward) | 5′-TTTTGAGAT |

| 5′-TTCATCAACATCATCCAAGTG-3′ (reverse) | 3′-TACAAGA | ||||||

| CdADP1 | 537 | 443 | +868-+1,404 | +868-+1,404 | 90 | 5′-GAGCCAAGTATGAATGACTTG-3′ (forward) | 5′-TACGTTGCAA |

| 5′-TTGATCAACAAACCCGATAAT-3′ (reverse) | 3′-GGAAATCCAA | ||||||

| CdGLN4 | 483 | 404 | +82-+564 | +82-+564 | 100 | 5′-GAGATAGTTAAGAATAAAAAAGTTG-3′ (forward) | 5′-TCTGCTTTA |

| 5′-GTCTCTTTCGTCTTTAGGACCCAATC-3′ (reverse) | 3′-TTCAAACC | ||||||

| CdMPIb | 486 | 375 | +406-+891 | +406-+892 | 90 | 5′-ACCAGAAATGGCC-3′ (forward) | 5′-TTTAAGC |

| 5′-GCAGCCATACATTCAATTAT-3′ (reverse) | 3′-GGGAAGCA | ||||||

| CdRPN2 | 447 | 306 | +1,012-+1,458 | +1,015-+1,461 | 90 | 5′-TTTATGCATGCTGGTACTACTGATG-3′ (forward) | 5′-TTGGTCCAAG |

| 5′-TAACCCCATACTCAAAGCAGCAGCCT-3′ (reverse) | 3′-GTCTTTACGA | ||||||

| CdSYA1 | 543 | 391 | +2,284-+2,826 | +2,284-+2,826 | 90 | 5′-AGAAGAATAGTTGCTCTTACTG-3′ (forward) | 5′-TAAATCCAAG |

| 5′-GTTGCCCTTACCACCAGCTTT-3′ (reverse) | 3′-AGTCTGTATCT | ||||||

| CdVPS13 (exCdVPS13) | 741 | 403 (675) | +4,854-+5,594 | +4,858-+5,598 | 88 | 5′-CGTTGAGAGATATTCGACTT-3′ (forward) | 5′-CCTTGATATG |

| 5′-ACGGATCGATCGCCAATCC-3′l (reverse) | 3′-AAAATCTTGG (5′-AGAGCAAACG) (3′-AAACCTTGG) | ||||||

| CdZWF1b (exCdZWF1b) | 702 | 491 (621) | +787-+1,469 | +766-+1,468 | 93 | 5′-GTTTCATTTGATCCTGAAGC-3′ (forward) | 5′-CAAACCAGG |

| 5′-GCCATTGATAAGTACCTGGAT-3′ (reverse) | 3′-TAGAATTAC (5′-AAAGTTTTAAAA) (3′-GAAAATATTTGAAA) | ||||||

Numbers in parentheses are for extended sequence fragments analyzed for polymorphisms.

Nucleotide coordinates for MLST amplicons are numbered based on the adenine residue of the ATG start codon at the 5′ end of the gene designated +1.

Sequence homology between C. dubliniensis and C. albicans at the sequenced fragments.

Nucleotide bases shown in bold typeface and underlined denote nucleotide bases that vary between C. albicans and C. dubliniensis.

Loci for which additional sequence data were analyzed in both the 5′ and 3′ directions of the original sequence fragment (range, 100 bp to 280 bp) due to the presence of additional polymorphic sites (underlined and bold). Sequences in parentheses are those used with the extended sequence fragments.

PCR amplification and sequence determination.

PCR assays were carried out in 50-μl reaction volumes containing a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.25 U of GoTaq polymerase (Promega), 10 μl (1×) of GoTaq FlexiBuffer (Promega), 3 μM MgCl2, 100 pmol of each primer, and 1 ng of the DNA template. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick 96-well PCR purification kit (Qiagen Science, MD) and were sequenced on both strands using the same primers that had been used previously for amplification. DNA sequencing reactions were performed commercially by Cogenics (Essex, United Kingdom) using an ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer.

Sequence analysis and sequence type determination.

Sequence analysis was performed by examination of chromatogram files using the ABI prism Seqscape software, version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequences of all of the loci examined are provided in the supplemental material. Numbers were assigned to unique genotypes for each locus, and genotype numbers were then combined to yield a diploid sequence type (DST) number. All genotype numbers and DST numbers are also available in the supplemental material. Maximum-parsimony trees and dendrograms based on analysis by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) were constructed using the Bionumerics software package, version 4.6 (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium), based on concatenated C. albicans and C. dubliniensis MLST sequences. The discriminatory power of each MLST scheme was determined using Hunter's formula (24).

Linkage disequilibrium and clonality.

Linkage disequilibrium was assessed using the index of association, as described by Smith et al. (44) and as calculated with the Multilocus 1.3 software package, available at http://www.agapow.net/software/multilocus/ (1), using genotype numbers for all loci (scheme C) from all 50 C. dubliniensis isolates. The levels of significance for nonrandom association between loci were computed under the null hypothesis of a freely recombining population (panmixia).

Stability and reproducibility of the MLST method.

The stability and reproducibility of the sequence data at each MLST locus were assessed by carrying out the sequence analysis in duplicate on two randomly selected isolates. For each locus and isolate, the duplicate DNA extractions, PCRs, and sequencing reactions were carried out independently. Resulting sequence duplicates for each isolate were compared to each other.

RESULTS

Development of an MLST scheme for C. dubliniensis.

All loci previously examined for the purpose of analyzing MLSTs in C. albicans were also investigated for their potential use with C. dubliniensis. Homologous genes were found in each case, and comparison of the sequences of the complete open reading frames of the orthologous pairs revealed homologies ranging from 89% to 94%, while the parts of the genes that were analyzed for MLST purposes displayed 88% to 100% sequence identity (Table 3).

The current consensus MLST scheme for C. albicans examines 2,883 nucleotides from seven loci: AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b. For the purposes of this study, this scheme is referred to as scheme A (Table 4). The corresponding scheme A loci were examined in the 50 C. dubliniensis isolates included in this study. The scheme A loci resulted in 23 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the equivalent 2,883 nucleotides (0.8%) and identified 33 genotypes. In scheme A, only one site (i.e., position 186 in SYA1) showed a polymorphism at the same position in both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, whereas all other variable sites were at different locations in the two species. Tavanti et al. analyzed eight loci (54) (AAT1a, AAT1b, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b) for sites of heterozygosity among 50 isolates of C. albicans. The group identified 87 sites that displayed polymorphisms, 71 of which (81.6%) also displayed heterozygosity. The same loci were studied for sites of heterozygosity in the 50 isolates of C. dubliniensis (Table 1), and of the 30 sites displaying variability, 9 (30%) displayed heterozygosity.

TABLE 4.

Summary of loci used in individual MLST schemes

| MLST scheme | Locusa

|

No. of polymorphic sites | No. of DSTs | Discriminatory powerb | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAT1a | AAT1b | ACC1 | ADP1 | GLN4 | MPIb | RPN2 | SYA1 | VPS13 | (ex)VPS13 | ZWF1b | (ex)ZWF1b | ||||

| A | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | 23 | 20 | 0.899 |

| B | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | 26 | 22 | 0.901 |

| C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | 37 | 26 | 0.910 |

| D | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | 32 | 25 | 0.909 |

| E | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | 26 | 22 | 0.906 |

+ and − denote the presence and absence, respectively, of individual loci in each MLST scheme.

Determined using Hunter's formula (24).

Due to the low levels of polymorphism observed in the C. dubliniensis loci examined, we investigated whether increasing the length of the sequences examined had the potential to increase the discriminatory power of the method. To achieve this, additional nucleotide sequence data (range, 100 bp to 280 bp) at each of the loci in both the 5′ and 3′ directions of the original sequence fragment were also analyzed for the potential presence of polymorphic sites. Sequence analysis of the extended fragments in CdVPS13 and CdZWF1b (exCdVPS13 and exCdZWF1b, respectively) revealed the presence of additional SNPs (Table 3). The inclusion of these two extended sequences together with the sequences of the other five loci generated a second MLST scheme, termed scheme B (Table 4), which was made up of the sequences of the CdAAT1a, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdMPIb, CdSYA1, exCdVPS13, and exCdZWF1b loci. Examination of exCdVPS13 revealed one extra SNP, which gave rise to two extra genotypes (Table 5), and exCdZWF1b yielded two further SNPs, which in turn gave rise to one extra genotype. Scheme B resulted in a new total of 3,285 nucleotides, 26 (0.8%) of which displayed SNPs, resulting in four additional genotypes (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Summary of characteristics of loci used in the MLST analysis

| Locus | Length of analyzed sequence | No. (%) of polymorphic nucleotide sites | No. of polymorphic amino acid sites | No. of resulting genotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAT1a | 373 | 1 (0.27) | 0 | 2 |

| AAT1b | 341 | 4 (1.17) | 2 | 5 |

| ACC1 | 407 | 3 (0.74) | 2 | 4 |

| ADP1 | 443 | 5 (1.13) | 1 | 6 |

| GLN4 | 404 | 4 (0.99) | 2 | 2 |

| MPIb | 375 | 2 (0.5) | 1 | 7 |

| RPN2 | 306 | 3 (0.98) | 0 | 3 |

| SYA1 | 391 | 5 (1.28) | 2 | 5 |

| VPS13 | 403 | 2 (0.5) | 1 | 2 |

| (ex)VPS13 | 675 | 3 (0.44) | 2 | 4 |

| ZWF1b | 491 | 5 (1.02) | 1 | 4 |

| (ex)ZWF1b | 621 | 7 (1.13) | 1 | 6 |

In a further attempt to improve the discriminatory power of this method for C. dubliniensis, three other sequence segments in C. dubliniensis that were previously investigated for possible use in the MLST analysis of C. albicans were also analyzed, although these were not included in the final consensus C. albicans MLST scheme. Sequences from these additional loci, CdAAT1b, CdGLN4, and CdRPN2 (Table 3), comprised an additional 1,051 nucleotides, 11 of which displayed SNPs (1.05%). The 10 sequence fragments (the scheme B loci and the three additional loci) were all analyzed together in a third scheme, termed scheme C (Table 4), which was based on the sequences of the CdAAT1a, CdAAT1b, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdGLN4, CdMPIb, CdRPN2, CdSYA1, exCdVPS13, and exCdZWF1b loci. CdGLN4 displayed four of the further 11 SNPs; however, it gave rise to only two genotypes among the 50 isolates investigated. Similarly, CdAAT1b displayed four SNPs, giving rise to five genotypes, and the CdRPN2 locus contained three polymorphic sites, which gave rise to three genotypes. Scheme C analyzed a total of 4,336 nucleotides, 37 of which (0.85%) displayed SNPs, resulting in a total of 48 genotypes from 50 C. dubliniensis isolates. The minimum number of MLST loci for maximum discrimination among isolates of C. dubliniensis was determined according to the highest number of genotypes per variable base in each locus (Table 4 and Table 5) and is referred to as scheme D, consisting of the eight loci CdAAT1b, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdMPIb, CdRPN2, CdSYA1, exCdVPS13, and exCdZWF1b. Scheme D displayed a total of 32 SNPs, resulting in 40 genotypes from the 50 isolates of C. dubliniensis investigated. Polymorphic sites and resulting genotypes are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Nucleotide polymorphisms and amino acid changes.

The effect of nucleotide polymorphism on the resulting amino acid sequence was investigated by mapping the triplet codons for each gene fragment and examining the effect that the SNP had on each codon in question. Nucleotide polymorphisms and amino acid substitutions are summarized in Table 6. Of the 37 SNPs identified in the 10 C. dubliniensis loci examined (with substitution of CdVPS13 for exCdVPS13 and CdZWF1b for exCdZWF1b), 13 (35%) resulted in nonsynonymous amino acid changes, while all of the remaining nucleotide changes resulted in synonymous polymorphisms. Seven of the 13 nonsynonymous polymorphisms affected the resulting amino acid substantially, i.e., affecting the pH (4 of 7) or polarity (3 of 7) of the amino acid.

TABLE 6.

Nucleotide polymorphisms and amino acid substitutions in C. dubliniensis locid

| Gene fragment | Nucleotide position showing polymorphisma | Triplet polymorphismb | Amino acidsc | Corresponding codon in C. albicans | Corresponding amino acid residue in C. albicans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdAAT1a | 2 | (T/C)TG | L/L | TTG | L |

| CdAAT1b | 105 | A(T/A)T | I/N | ATC | I |

| 114 | TC(A/T) | S/S | TCA | S | |

| 121 | (G/A)AA | E/K | GAA | E | |

| 129 | TC(T/G) | S/S | TCT | S | |

| CdACC1 | 128 | TT(T/C) | F/F | TTC | F |

| 313 | T(T/C)G | L/S | CTG | L | |

| 390 | AA(A/T) | K/N | AAA | K | |

| CdADP1 | 31 | AT(C/T) | I/I | ATT | I |

| 214 | AG(C/T) | S/S | AGT | S | |

| 234 | G(A/G)G | E/G | GAG | E | |

| 331 | TG(T/C) | C/C | TGT | C | |

| 421 | TC(G/T) | S/S | TCA | S | |

| CdGLN4 | 104 | GA(A/T) | E/D | GTA | V |

| 141 | AA(T/C) | N/N | AAA | K | |

| 147 | GA(T/C) | D/D | GAC | D | |

| 244 | (A/G)TT | I/V | ATT | I | |

| CdMPIb | 101 | A(G/A)A | R/K | AGA | R |

| 375 | GC(A/G) | A/A | GCA | A | |

| CdRPN2 | 127 | TC(C/A) | S/S | TCC | S |

| 136 | GC(C/T) | A/A | GCC | A | |

| 298 | GC(T/C) | A/A | GCA | A | |

| CdSYA1 | 82 | AA(C/T) | N/N | AAT | N |

| 148 | TT(A/G) | L/L | TTA | L | |

| 186 | AA(T/C) | N/N | AAT | N | |

| 203 | G(T/C)T | V/A | GTT | V | |

| 383 | (T/G)CT | S/A | GCT | A | |

| CdVPS13 | 397* | AA(A/G) | K/K | AAG | K |

| 402† | T(G/C)G | W/S | TGG | W | |

| exCdVPS13 | 45 | GA(G/C) | E/D | GAC | D |

| 654* | AA(A/G) | K/K | AAG | K | |

| 659† | T(G/C)G | W/S | TGG | W | |

| CdZWF1b | 1‡ | AC(C/T) | T/T | AAA | K |

| 28§ | AC(G/A) | T/T | ACC | T | |

| 265¶ | AA(G/A) | K/K | AAA | K | |

| 299‖ | (G/T)AT | D/Y | GAT | D | |

| 334# | AA(A/G) | K/K | AAA | K | |

| exCdZWF1b | 78‡ | AC(C/T) | T/T | AAA | K |

| 105§ | AC(G/A) | T/T | ACC | T | |

| 342¶ | AA(G/A) | K/K | AAA | K | |

| 376‖ | (G/T)AT | D/Y | GAT | D | |

| 411# | AA(A/G) | K/K | AAA | K | |

| 573 | TA(T/C) | Y/Y | TAT | Y | |

| 588 | TC(A/T) | S/S | TCA | S |

Nucleotide positions refer to the positions in the analyzed fragment only.

Position of the polymorphism relative to its codon.

Amino acid resulting from the codon both before and after polymorphism.

The nucleotide sites shown in bold typeface and underlined denote the only common nucleotide sites that display polymorphism in both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis. Identical polymorphic sites in both of the extended gene segments analyzed and in the shorter sequences that were based on the C. albicans scheme lengths are marked with the same symbols.

Stability and reproducibility of C. dubliniensis MLST.

Sequence analysis was performed in duplicate for each of two randomly selected isolates (Table 1) per MLST locus, using independently prepared DNA, PCR, and sequencing reactions. For each MLST locus, duplicate sequences for each isolate showed 100% sequence identity, displaying full conservation of both SNPs and sites of heterozygosity at each locus.

C. dubliniensis strain differentiation by MLST.

Examination of the C. albicans MLST locus set (scheme A) in the 50 C. dubliniensis isolates investigated identified 20 unique DSTs based on the unique combinations of the genotype numbers for the seven loci examined. Application of Hunter's formula (24) to this data set infers that MLST using scheme A has a discriminatory power of 0.899 when applied to C. dubliniensis, compared with a value of 0.996 when applied to C. albicans (35). Extension of the CdVPS13 and CdZWF1b loci (scheme B) resulted in a further 2 DSTs, and adding the CdAAT1b, CdGLN4, and CdRPN2 loci (scheme C in Table 4) resulted in a further 4 DSTs, giving a total of 26 DSTs from the 10 loci. Extending the CdZWF1b and CdVPS13 gene fragments and including the three other loci in scheme C increased the discriminatory power to 0.9102 (Table 4). DST 4 was the most common DST identified using the scheme A set of loci in C. dubliniensis, corresponding to 14 of the 50 isolates examined. The set of seven loci identified 11 DSTs that were unique to single C. dubliniensis isolates. When the larger set of loci was used in scheme C, the same 14 isolates from DST 4 in scheme A referred to above also gave an identical sequence type, this time termed DST 7, which correlated with the previously identified DST 4, making this the most common DST in the scheme examined for C. dubliniensis. Using this larger set of loci, 19 of the 26 DSTs were unique to single isolates.

Population analysis of C. dubliniensis using MLST.

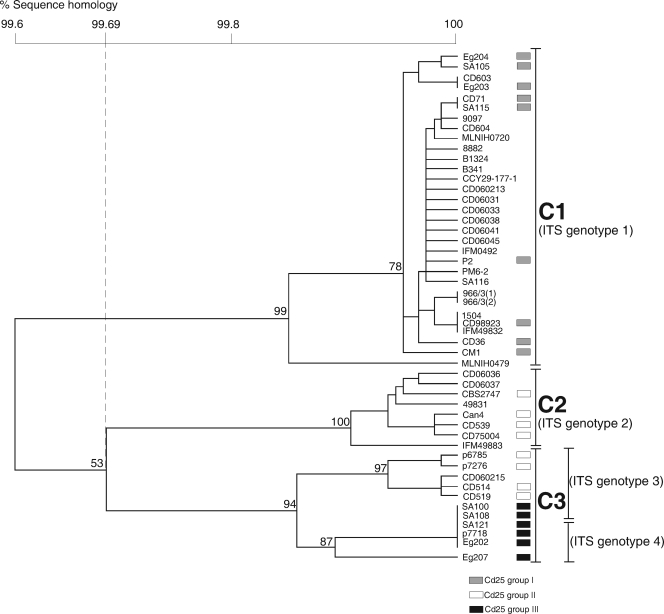

A UPGMA dendrogram was constructed based on the sequence data from all 10 loci (scheme C) examined in C. dubliniensis by using the Bionumerics version 4.6 software program (Fig. 1). At a cutoff node of 99.7% sequence homology, the dendrogram revealed the presence of three major clades of isolates termed C1 to C3, which showed a significant degree of correlation with the major clades previously identified by fingerprinting using the Cd25 fingerprint probe (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Clades C1 and C2 corresponded to the previously identified Cd25 fingerprint groups I and II, respectively, whereas clade C3 included strains previously identified as belonging to Cd25 fingerprint groups II and III, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Furthermore, clade C1 consisted solely of ITS genotype 1 isolates, clade C2 consisted solely of ITS genotype 2 isolates, whereas clade C3 consisted of ITS genotype 3 and 4 isolates.

FIG. 1.

UPGMA dendrogram based on concatenated sequences from the MLST scheme C loci CdAAT1a, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdMPIb, CdSYA1, exCdVPS13, exCdZWF1b, CdRPN2, CdGLN4, and CdAAT1b (Table 3), showing percentages of sequence homology for 50 C. dubliniensis isolates from a broad range of geographical locations, including isolates from all known ITS genotypes (Table 1). Three distinct major clades termed clades C1 to C3 are evident at 99.69% sequence homology. C1 consists of ITS genotype 1 isolates exclusively, C2 consists of ITS genotype 2 isolates exclusively, and C3 consists of ITS genotype 3 and 4 isolates. Twenty-three of the 50 isolates included in the study were previously fingerprinted with the C. dubliniensis-specific probe Cd25 (4, 21), and the Cd25 fingerprint groups of these isolates are indicated by shaded rectangular boxes.

Linkage disequilibrium and clonality.

Genetic diversity and linkage disequilibria were assessed by using statistics implemented in the Multilocus 1.3 software (1) and genotypes obtained for all loci investigated in this study (scheme C). Each of these statistics tested the null hypothesis of a freely recombining population. Highly significant linkage disequilibria (P was <10−5 with 100,000 randomizations) were found for both the total collection of 50 C. dubliniensis isolates and a reduced collection of 26 isolates that represented each of the 26 DSTs defined by scheme C (i.e., that did not contain repeated genotypes) (data not shown). These results provide evidence that the sample of C. dubliniensis isolates analyzed in this study represents a clonal population.

Comparative population analysis of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis using MLST.

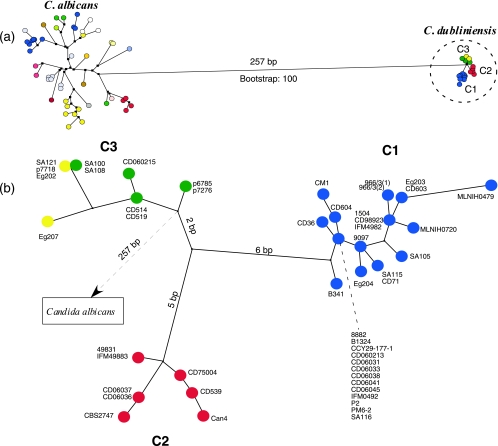

C. albicans MLST sequences were available for the seven consensus MLST loci (i.e., AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b) and an extra locus, RPN2. The resulting 3,189 nucleotides from the eight loci resulted in a fifth scheme, termed scheme E (Table 4). All locus sequences were concatenated and treated as one sequence for each of 50 C. albicans isolates and the corresponding sequences in 50 C. dubliniensis isolates in order to allow comparison between the two species using MLST. These concatenated sequences were used to construct a maximum-parsimony tree in order to assess comparative phylogenies between the species (Fig. 2). The maximum-parsimony tree displays the comparative divergence within the two species, as well as the level of relatedness between the two species. The maximum-parsimony tree demonstrated that C. albicans isolates belonging to different MLST clades can differ at as many as 90 nucleotide sites but that isolates belonging to the same MLST clade can differ at as many as 31 nucleotide sites (data not shown). In contrast, our data showed that C. dubliniensis consisted of three closely related clades, termed clades C1, C2, and C3 (Fig. 2), that show complete agreement with the clades described by the UPGMA dendrogram (Fig. 1). C. dubliniensis isolates from the three MLST clades differ from each other at a minimum of 10 nucleotide sites (range, 10 to 23 nucleotides). Isolates belonging to clade C1 differ at a maximum of 10 nucleotide sites, isolates belonging to clade C2 differ at a maximum of 6 nucleotide sites, and isolates belonging to clade C3 differ at a maximum of 8 nucleotide sites (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Maximum-parsimony tree showing the comparative divergences between 50 isolates each of C. albicans and C. dubliniensis based on concatenated sequences from the MLST loci AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, ZWF1b, and RPN2 in MLST scheme E. C. dubliniensis isolates were selected from a diverse range of geographic locations and from all four ITS genotypes (Table 1). C. albicans isolates were selected as representatives of the MLST clades recently described by Odds et al. (35) (Table 2). (a) Comparative divergence between the C. albicans and C. dubliniensis isolates tested showing that the two species are separated by 257-bp differences. The C. dubliniensis isolates formed three closely related groups of isolates (C1 to C3), which correspond to those identified in the UPGMA dendrogram shown in Fig. 1. Isolates from distinct clades are highlighted by specific colors for each species. (b) Enlarged view of the three C. dubliniensis major clades encircled in panel a. Clade C1 consists exclusively of ITS genotype 1 isolates (blue), clade C2 consists exclusively of ITS genotype 2 isolates (red), and clade C3 consists of ITS genotype 3 isolates (green) and ITS genotype 4 isolates (yellow).

DISCUSSION

MSLT has previously been shown to be a useful tool in the analysis of the epidemiology and population structure of C. albicans (8-10, 35, 52, 54). The purpose of the present study was to determine the usefulness of MLST in the analysis of C. dubliniensis. In addition, we investigated whether the same set of MLST loci currently used for C. albicans could be applied to the analysis of C. dubliniensis due to the high levels of nucleotide sequence homology (∼90%) shared by the two species, thus allowing comparative sequence data to be used to provide valuable information concerning the evolutionary relatedness of the two species.

The current MLST scheme in use for isolates for C. albicans examines seven loci: AAT1a, ACC1, ADP1, MPIb, SYA1, VPS13, and ZWF1b (scheme A in Table 4) and was also applied in the analysis of C. dubliniensis isolates. It demonstrated poor levels of discrimination among C. dubliniensis isolates, identifying only 20 DSTs from 50 isolates. SNPs have been detected in 172 of these 2,883 nucleotides (6%) in C. albicans (5). To date, 1,391 isolates of C. albicans have been examined, identifying 1,005 DSTs (35). An identical scheme demonstrated poor levels of discrimination among C. dubliniensis isolates, identifying only 20 DSTs from 50 isolates. Discriminatory powers were improved by extension of the CdVPS13 and CdZWF1b loci and by incorporation of an additional three loci, AAT1b, GLN4, and RPN2, which had also previously been examined for use in the MLST analysis of C. albicans. The scheme (i.e., scheme C) which examined the largest number of loci (Table 4) identified 26 DSTs from the 50 C. dubliniensis isolates. The 10 loci included in scheme C were concatenated and used in the construction of a UPGMA dendrogram (Fig. 1), which clustered the isolates into three distinct major clades at a cutoff sequence homology of 99.7%. A maximum-parsimony tree (Fig. 2) was also constructed using concatenated sequence data, this time with a further scheme, scheme E (Table 4), which was based on the seven loci from scheme A and an extra locus, RPN2 (Table 4). Sequence data for these eight loci were available for both C. albicans and C. dubliniensis, thus enabling the comparative study of the population structures for both species. Our study shows that the C. albicans clades are more divergent than those observed in C. dubliniensis (Fig. 2). The maximum-parsimony tree identified three distinct major clades (C1 to C3) in the population of C. dubliniensis, which were identical to those of the UPGMA dendrogram (Fig. 1). Overall, 257 nucleotides of the 3,189 nucleotides analyzed (8%) were identified as being different between the two species, correlating with the level of sequence homology typically exhibited between the two species (33).

The population structure of C. dubliniensis as determined by MLST correlated with the population structure previously determined using the complex fingerprinting probe Cd25 and on the basis of ITS genotypes (4, 21, 26). In previous studies, isolates assigned to ITS genotype 1 belonged exclusively to Cd25 group I (4, 21, 26). Similarly, by the MLST method, all of the ITS genotype 1 isolates tested belonged to MLST clade C1 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Cd25 group II was previously shown to consist of isolates belonging to ITS genotypes 2, 3, and 4 (21). The MLST method breaks Cd25 group II into two groups, assigning all of the ITS genotype 2 isolates to MLST clade C2 exclusively and assigning the ITS genotype 3 and 4 isolates to MLST clade C3 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Interestingly, a number of ITS genotype 3 and 4 isolates in MLST clade C3 displayed the same DST and localized to the same area on both the UPGMA and maximum-parsimony trees (Fig. 1 and 2). These isolates were all previously associated with Cd25 fingerprint group III (Table 1) and displayed high levels of resistance to the antifungal drug 5-flucytosine (4). The agreement between these three methods suggests that MLST may be applied as a reliable alternative method for studying the population structure of C. dubliniensis. MLST is less time-consuming, more reproducible, and more conducive to comparison between laboratories than other methods previously used for this purpose.

The best set of eight loci (CdAAT1b, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdMPIb, CdRPN2, CdSYA1, exCdVPS13, and exCdZWF1b) proposed for maximum discrimination among isolates of C. dubliniensis using the minimum number of MLST loci possible was determined according to the highest number of genotypes per variable base in each locus and is referred to as scheme D (Table 4). The AAT1b locus is no longer included among the more discriminatory seven loci currently recommended for use in C. albicans MLST studies (10), and therefore the corresponding CdAAT1b locus should be replaced with the CdAAT1a locus for the purpose of comparative population analysis between the two species. The eight loci recommended for the purposes of comparative population analysis between C. albicans and C. dubliniensis using MLST are therefore from scheme E: CdAAT1a, CdACC1, CdADP1, CdMPIb, CdRPN2, CdSYA1, CdVPS13, and CdZWF1b (Table 4).

The MLST data suggest a relatively low level of divergence in the population structure of C. dubliniensis relative to that of C. albicans. Interestingly, this is in contrast to the findings of electrophoretic karyotypic analysis showing that isolates of C. dubliniensis have significantly different major karyotypic patterns due to the processes of microevolution and chromosomal rearrangement (21). The low level of sequence variation throughout the population of C. dubliniensis suggests that MLST may not be ideal for local epidemiological studies (e.g., an outbreak in a hospital); in this instance, karyotypic analysis may be more appropriate. Karyotype analysis was able to distinguish the Cd25 group I and II isolates to a large extent but was unable to distinguish among the ITS genotypes. In comparison, the MLST method is able to distinguish readily among certain ITS genotypes, most notably the ITS genotype 1 and 2 isolates. ITS genotype 3 and 4 isolates could not be distinguished reliably by MLST, due to the lack of sequence variation among these isolates, the majority of which to date have been recovered from the Middle East. However, results may possibly be improved with the inclusion of a larger number of ITS genotype 3 and 4 isolates from geographical locations outside of the Middle East. A possible reason for the low level of discrimination is the relatively small collection of isolates studied. However, isolates were recovered from a broad range of geographical locations and included isolates recovered from both carriage and systemic infection. Another possible reason for the low level of sequence variation and heterozygosity is the lack of divergence within the population of C. dubliniensis strains. Results of genotypic diversity and linkage diversity analyses suggested that the sample of 50 C. dubliniensis isolates investigated in this study represent a clonal population. However, it is important to emphasize that the sample number was relatively small, even though many of the isolates were recovered from disparate geographic locations around the world. Furthermore, it is possible that a more diverse population of C. dubliniensis strains exists in nonhuman hosts and that this is not reflected in the present study (see below). Finally, the recent divergence of C. dubliniensis from its ancestor C. albicans suggests a C. dubliniensis population that is less divergent than that of C. albicans, as the latter has had more time to diverge into major and minor clades. C. dubliniensis is a poor pathogen in comparison to C. albicans, since it rarely causes infections in healthy individuals and therefore may be under less pressure to adapt to different host environments. However, it is also possible that the natural host/reservoir for C. dubliniensis is not humans. Candida species have also been recovered from nonhuman hosts, such as dogs, cats, birds, and chameleons (12, 14, 41, 52). Recent environmental studies have reported the recovery of ITS genotype 1 C. dubliniensis isolates from Ixodes uriae ticks on the Great Saltee Island off southeastern Ireland (34), the supposed source being bird excrement. Candida species such as C. albicans, C. guilliermondii, and C. tropicalis have been recovered previously from the gastrointestinal tracts and cloacae of birds (12, 14, 23). It is conceivable that humans represent only a minority host for C. dubliniensis and that the isolates studied to date represent a relatively small subpopulation of the species. In order to investigate this possibility further, it will be necessary to increase the number of isolates analyzed by MLST, including isolates from avian and possibly other nonhuman hosts. We anticipate that such additional studies will identify additional MLST clades. These studies are currently in progress. Further studies will also include investigating the levels of recombination events in C. dubliniensis, as Odds et al. have recently shown that a high frequency of recombination is apparent in C. albicans (35).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Microbiology Research Unit, Dublin Dental School & Hospital. D.D. is the recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship from the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 December 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agapow, P. M., and A. Burt. 2001. Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Notes 1101-102. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Mosaid, A., D. Sullivan, I. F. Salkin, D. Shanley, and D. C. Coleman. 2001. Differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans on Staib agar and caffeic acid-ferric citrate agar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39323-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Mosaid, A., D. J. Sullivan, and D. C. Coleman. 2003. Differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans on Pal's agar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 414787-4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Mosaid, A., D. J. Sullivan, I. Polacheck, F. A. Shaheen, O. Soliman, S. Al Hedaithy, S. Al Thawad, M. Kabadaya, and D. C. Coleman. 2005. Novel 5-flucytosine-resistant clade of Candida dubliniensis from Saudi Arabia and Egypt identified by Cd25 fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 434026-4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bain, J. M., A. Tavanti, A. D. Davidson, M. D. Jacobsen, D. Shaw, N. A. Gow, and F. C. Odds. 2007. Multilocus sequence typing of the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451469-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blignaut, E., C. Pujol, S. Lockhart, S. Joly, and D. R. Soll. 2002. Ca3 fingerprinting of Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive and healthy individuals reveals a new clade in South Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40826-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bougnoux, M. E., D. M. Aanensen, S. Morand, M. Theraud, B. G. Spratt, and C. d'Enfert. 2004. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida albicans: strategies, data exchange and applications. Infect. Genet. Evol. 4243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bougnoux, M. E., D. Diogo, N. Francois, B. Sendid, S. Veirmeire, J. F. Colombel, C. Bouchier, H. Van Kruiningen, C. d'Enfert, and D. Poulain. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing reveals intrafamilial transmission and microevolutions of Candida albicans isolates from the human digestive tract. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441810-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bougnoux, M. E., S. Morand, and C. d'Enfert. 2002. Usefulness of multilocus sequence typing for characterization of clinical isolates of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401290-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bougnoux, M. E., A. Tavanti, C. Bouchier, N. A. Gow, A. Magnier, A. D. Davidson, M. C. Maiden, C. D'Enfert, and F. C. Odds. 2003. Collaborative consensus for optimized multilocus sequence typing of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 415265-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle, B. M., D. J. Sullivan, C. Forkin, F. Mulcahy, C. T. Keane, and D. C. Coleman. 2002. Candida dubliniensis candidaemia in an HIV-positive patient in Ireland. Int. J. STD AIDS 1355-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buck, J. D. 1990. Isolation of Candida albicans and halophilic Vibrio spp. from aquatic birds in Connecticut and Florida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56826-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bujdakova, H., S. Melkusova, I. Soji, M. Mokras, and Y. Mikami. 2004. Discrimination between Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis isolated from HIV-positive patients by using commercial method in comparison with PCR assay. Folia Microbiol. (Prague) 49484-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cafarchia, C., A. Camarda, D. Romito, M. Campolo, N. C. Quaglia, D. Tullio, and D. Otranto. 2006. Occurrence of yeasts in cloacae of migratory birds. Mycopathologia 161229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan-Tack, K. M. 2005. Fatal Candida dubliniensis septicemia in a patient with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 401209-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, K. W., Y. C. Chen, H. J. Lo, F. C. Odds, T. H. Wang, C. Y. Lin, and S. Y. Li. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing for analyses of clonality of Candida albicans strains in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442172-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodgson, A. R., C. Pujol, D. W. Denning, D. R. Soll, and A. J. Fox. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida glabrata reveals geographically enriched clades. J. Clin. Microbiol. 415709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donnelly, S. M., D. J. Sullivan, D. B. Shanley, and D. C. Coleman. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis and rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis based on analysis of ACT1 intron and exon sequences. Microbiology 1451871-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fell, J. W. 1993. Rapid identification of yeast species using three primers in a polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 2174-180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher, P. J., D. E. Bennett, M. C. Henman, R. J. Russell, S. R. Flint, D. B. Shanley, and D. C. Coleman. 1992. Reduced azole susceptibility of oral isolates of Candida albicans from HIV-positive patients and a derivative exhibiting colony morphology variation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1381901-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gee, S. F., S. Joly, D. R. Soll, J. F. Meis, P. E. Verweij, I. Polacheck, D. J. Sullivan, and D. C. Coleman. 2002. Identification of four distinct genotypes of Candida dubliniensis and detection of microevolution in vitro and in vivo. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40556-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilfillan, G. D., D. J. Sullivan, K. Haynes, T. Parkinson, D. C. Coleman, and N. A. Gow. 1998. Candida dubliniensis: phylogeny and putative virulence factors. Microbiology 144829-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasenclever, H. F., and R. M. Kogan. 1975. Candida albicans associated with the gastrointestinal tract of the common pigeon (Columbia livia). Sabouraudia 13116-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter, P. R. 1990. Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 281903-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsen, M. D., N. A. Gow, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, and F. C. Odds. 2007. Strain typing and determination of population structure of Candida krusei by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45317-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joly, S., C. Pujol, M. Rysz, K. Vargas, and D. R. Soll. 1999. Development and characterization of complex DNA fingerprinting probes for the infectious yeast Candida dubliniensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 371035-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kibbler, C. C., S. Seaton, R. A. Barnes, W. R. Gransden, R. E. Holliman, E. M. Johnson, J. D. Perry, D. J. Sullivan, and J. A. Wilson. 2003. Management and outcome of bloodstream infections due to Candida species in England and Wales. J. Hosp. Infect. 5418-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maiden, M. C., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 953140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marriott, D., M. Laxton, and J. Harkness. 2001. Candida dubliniensis candidemia in Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMullan, R., J. Xu, J. E. Moore, B. C. Millar, M. J. Walker, S. T. Irwin, J. Price, J. Barr, and S. Hedderwick. 2002. Candida dubliniensis bloodstream infection in patients with gynaecological malignancy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21635-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meis, J. F., M. Ruhnke, B. E. De Pauw, F. C. Odds, W. Siegert, and P. E. Verweij. 1999. Candida dubliniensis candidemia in patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and bone marrow transplantation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5150-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melkusova, S., M. Lisalova, P. Pavlik, and H. Bujdakova. 2005. The first clinical isolates of Candida dubliniensis in Slovakia. Mycopathologia 159369-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran, G., C. Stokes, S. Thewes, B. Hube, D. C. Coleman, and D. Sullivan. 2004. Comparative genomics using Candida albicans DNA microarrays reveals absence and divergence of virulence-associated genes in Candida dubliniensis. Microbiology 1503363-3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunn, M. A. 2007. Environmental source of Candida dubliniensis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13747-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Odds, F. C., M. E. Bougnoux, D. J. Shaw, J. M. Bain, A. D. Davidson, D. Diogo, M. D. Jacobsen, M. Lecomte, S. Y. Li, A. Tavanti, M. C. Maiden, N. A. Gow, and C. d'Enfert. 2007. Molecular phylogenetics of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 61041-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Odds, F. C., A. D. Davidson, M. D. Jacobsen, A. Tavanti, J. A. Whyte, C. C. Kibbler, D. H. Ellis, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, and N. A. Gow. 2006. Candida albicans strain maintenance, replacement, and microvariation demonstrated by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443647-3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pincus, D. H., D. C. Coleman, W. R. Pruitt, A. A. Padhye, I. F. Salkin, M. Geimer, A. Bassel, D. J. Sullivan, M. Clarke, and V. Hearn. 1999. Rapid identification of Candida dubliniensis with commercial yeast identification systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 373533-3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinjon, E., D. Sullivan, I. Salkin, D. Shanley, and D. Coleman. 1998. Simple, inexpensive, reliable method for differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 362093-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polacheck, I., J. Strahilevitz, D. Sullivan, S. Donnelly, I. F. Salkin, and D. C. Coleman. 2000. Recovery of Candida dubliniensis from non-human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Israel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38170-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponton, J., R. Ruchel, K. V. Clemons, D. C. Coleman, R. Grillot, J. Guarro, D. Aldebert, P. Ambroise-Thomas, J. Cano, A. J. Carrillo-Munoz, J. Gene, C. Pinel, D. A. Stevens, and D. J. Sullivan. 2000. Emerging pathogens. Med. Mycol. 38(Suppl. 1)225-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pressler, B. M., S. L. Vaden, I. F. Lane, L. D. Cowgill, and J. A. Dye. 2003. Candida spp. urinary tract infections in 13 dogs and seven cats: predisposing factors, treatment, and outcome. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 39263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pujol, C., M. Pfaller, and D. R. Soll. 2002. Ca3 fingerprinting of Candida albicans bloodstream isolates from the United States, Canada, South America, and Europe reveals a European clade. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402729-2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robles, J. C., L. Koreen, S. Park, and D. S. Perlin. 2004. Multilocus sequence typing is a reliable alternative method to DNA fingerprinting for discriminating among strains of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 422480-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith, J. M., N. H. Smith, M. O'Rourke, and B. G. Spratt. 1993. How clonal are bacteria? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 904384-4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soll, D. R. 2000. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13332-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soll, D. R., and C. Pujol. 2003. Candida albicans clades. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stokes, C., G. P. Moran, M. J. Spiering, G. T. Cole, D. C. Coleman, and D. J. Sullivan. 2007. Lower filamentation rates of Candida dubliniensis contribute to its lower virulence in comparison with Candida albicans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44920-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan, D., K. Haynes, J. Bille, P. Boerlin, L. Rodero, S. Lloyd, M. Henman, and D. Coleman. 1997. Widespread geographic distribution of oral Candida dubliniensis strains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35960-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sullivan, D. J., G. P. Moran, and D. C. Coleman. 2005. Candida dubliniensis: ten years on. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2539-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan, D. J., G. P. Moran, E. Pinjon, A. Al-Mosaid, C. Stokes, C. Vaughan, and D. C. Coleman. 2004. Comparison of the epidemiology, drug resistance mechanisms, and virulence of Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 4369-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullivan, D. J., T. J. Westerneng, K. A. Haynes, D. E. Bennett, and D. C. Coleman. 1995. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 1411507-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tavanti, A., A. D. Davidson, M. J. Fordyce, N. A. Gow, M. C. Maiden, and F. C. Odds. 2005. Population structure and properties of Candida albicans, as determined by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435601-5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tavanti, A., A. D. Davidson, E. M. Johnson, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, N. A. Gow, and F. C. Odds. 2005. Multilocus sequence typing for differentiation of strains of Candida tropicalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435593-5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tavanti, A., N. A. Gow, S. Senesi, M. C. Maiden, and F. C. Odds. 2003. Optimization and validation of multilocus sequence typing for Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413765-3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 224673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vilela, M. M., K. Kamei, A. Sano, R. Tanaka, J. Uno, I. Takahashi, J. Ito, K. Yarita, and M. Miyaji. 2002. Pathogenicity and virulence of Candida dubliniensis: comparison with C. albicans. Med. Mycol. 40249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White, T. J., T. D. Bruns, S. B. Lee, and J. W. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p. 315-322. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sininsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.