Abstract

Under specific environmental conditions, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae can undergo a morphological switch to a pseudohyphal growth pattern. Pseudohyphal differentiation is generally studied upon induction by nitrogen limitation in the presence of glucose. It is known to be controlled by several signaling pathways, including mitogen-activated protein kinase, cyclic AMP-protein kinase A (cAMP-PKA), and Snf1 kinase pathways. We show that the alpha-glucoside sugars maltose and maltotriose, and especially sucrose, are more potent inducers of filamentation than glucose. Sucrose even induces filamentation in nitrogen-rich media and in the mep2Δ/mep2Δ ammonium permease mutant on ammonium-limiting medium. We demonstrate that glucose also inhibits filamentation by means of a pathway parallel to the cAMP-PKA pathway. Deletion of HXK2 shifted the pseudohyphal growth pattern on glucose to that of sucrose, while deletion of SNF4 abrogated filamentation on both sugars, indicating a negative role of glucose repression and a positive role for Snf1 activity in the control of filamentation. In all strains and in all media, sucrose induction of filamentation is greatly diminished by deletion of the sucrose/glucose-sensing G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr1, whereas it has no effect on induction by maltose and maltotriose. The competence of alpha-glucoside sugars to induce filamentation is reflected in the increased expression of the cell surface flocculin gene FLO11. In addition, sucrose is the only alpha-glucoside sugar capable of rapidly inducing FLO11 expression in a Gpr1-dependent manner, reflecting the sensitivity of Gpr1 for this sugar and its involvement in rapid sucrose signaling. Our study identifies sucrose as the most potent nutrient inducer of pseudohyphal growth and shows that glucose inactivation of Snf1 kinase signaling is responsible for the lower potency of glucose.

Under appropriate nutrient conditions, the baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae can undergo a transition from globular, yeast-like growth to a pseudohyphal, filamentous growth pattern, which is characterized by an elongated cell morphology and a polarized budding pattern (7). Pseudohyphal differentiation of diploid yeast cells is triggered on solid agar medium under ammonium-limiting conditions and in the presence of a fermentable carbon source (7). Filamentous growth is controlled by several signaling pathways. The mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway and the cyclic AMP-protein kinase A (cAMP-PKA) pathway, both of which are activated by Ras2, act upstream of the filamentation-specific MAP kinase Kss1 and PKA, respectively. Both kinases control the activities of downstream transcription factors by phosphorylation to induce the expression of the cell surface flocculin gene FLO11 (reviewed in reference 5). Pseudohyphal growth is also known to be controlled by the Snf1 kinase. Snf1 interacts with two repressor proteins, Nrg1 and Nrg2, which repress filamentation and other FLO11-dependent processes, such as haploid invasive growth and biofilm formation (11). Although the role of these signal transduction pathways in filamentous growth is well established, the upstream detection mechanisms that activate them in response to the nutrient status are poorly understood.

The cAMP-PKA pathway is directly activated by sugars through the G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr1. It has recently been shown that both glucose and sucrose are direct ligands for Gpr1 and that the affinity of Gpr1 for sucrose is significantly higher than for glucose (50% effective concentrations [EC50s], ±0.5 mM and ±20 mM, respectively) (12). Previous work has identified Gpr1 as a regulator of pseudohyphal differentiation on different fermentable carbon sources (18). Here, we have investigated the role of Gpr1 in the induction of filamentation on sucrose. We show that Gpr1 participates, together with Snf1-mediated signaling, in the induction of pseudohyphal growth on sucrose. We also demonstrate that signaling through Gpr1 triggers filamentous growth on sucrose under ammonium-rich conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains.

Standard methods were used for yeast culture and genetic analysis (1). All strains were congenic with Σ1278b and are listed in Table 1. gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ strains were made prototrophic by transformation with a plasmid containing the appropriate marker: YCplac33/GPR1 (10) and YCplac33 (6) for strains indicated as wild type and gpr1Δ, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SV18 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 gpr1::LEU2/gpr1::LEU2 | This study |

| SV19 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 gpa2::URA3/gpa2::URA3 | This study |

| SV82 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 tpk2::KanMX4/tpk2::KanMX4 | This study |

| SV132 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 gpr1::LEU2/gpr1::LEU2 tec1::KanMX4/tec1::KanMX4 | This study |

| SV20 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 flo11::URA3/flo11::URA3 | This study |

| SV45 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 mep2::LEU2/mep2::LEU2 gpr1::LEU2/gpr1::LEU2 | This study |

| SV156 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 gpr1::LEU2/gpr1::LEU2 hxk2::KanMX4/hxk2::KanMX4 | This study |

| SV173 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 gpr1::LEU2/gpr1::LEU2 snf4::KanMX4/snf4::KanMX4 | This study |

| SV152 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 gpr1::LEU2/gpr1::LEU2 agt1::KanMX4/agt1::KanMX4 | This study |

| SV143 | MATa/MATα leu2 ura3 cyr1::KanMX4/cyr1::KanMX4 yak1::URA3/yak1::URA3 pde2::KanMX4/pde2::KanMX4 | This study |

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Culture samples for total RNA extraction were cooled by the addition of ice-cold water. Total RNA was extracted from yeast cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). From 1 μg of total RNA, first-strand cDNA was prepared with the Promega avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcription system. Relative quantification of FLO11 and ACT1 was determined with the Platinum SYBR Green qPCR kit (Invitrogen) and the following primers for FLO11: For, 5′-GCAGTCGCTACATACTCTGT-3′, and Rev, 5′-AAGAGCGAGTAGCAACCACA-3′. For ACT1 the primers were For, 5′-CGTCTGGATTGGTGGTTCTA-3′, and Rev, 5′-GGTGAACGATAGATGGACCA-3′.

Monitoring of pseudohyphal growth.

Pseudohyphal growth was monitored after 24 h on nitrogen-limiting (synthetic low ammonium [SLA]) medium as described previously (7). Hot agar medium supplemented with the appropriate sugars was poured onto a single-well microscope slide, and its surface was flattened with a second slide. Overnight cultures were washed twice in water and diluted to approximately 500 cells/μl. Ten microliters of this suspension was spotted on the agar surface, covered with a 24- by 50-mm coverslip, and incubated at 30°C in a moisturized sterile petri dish. Microscopic images of microcolonies were acquired with a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope and a Zeiss Axiocam MRc 5.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The alpha-glucoside sugars, sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose, are more potent inducers of pseudohyphal growth than glucose.

Pseudohyphal differentiation is generally studied upon induction by nitrogen limitation in the presence of glucose. We studied the onset of dimorphic growth on different sugars in microcolonies at a microscopic level. We scored pseudohyphal growth by assessing the degree of filament formation emerging from the center of the microcolony, i.e., the fraction of pseudohyphae in a colony consisting of elongated yeast cells with a polarized budding pattern. Elongated cells not projecting from the microcolony as pseudohyphae were not considered to contribute to pseudohyphal growth. We show that the alpha-glucoside sugars, sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose, are more potent inducers than glucose. Figure 1A shows that sucrose is a better inducer of filamentation than glucose at both 10 and 100 mM. Figure 1B shows that 100 mM maltose or maltotriose has a potency similar to that of 100 mM sucrose. Microcolonies growing on fructose and mannose showed a pseudohyphal growth pattern similar to that on glucose, displaying a limited number of cells in a dimorphic growth pattern (results not shown). This is consistent with a previous report in which the partial filamentous growth phenotype of cells in a diploid colony growing on glucose was correlated with the epigenetic on state of the cell surface flocculin Flo11 (8).

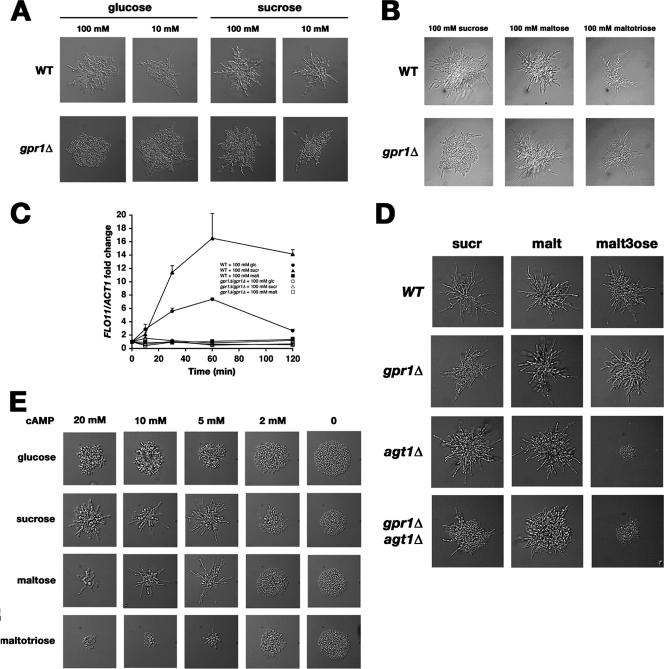

FIG. 1.

Induction of pseudohyphal growth by alpha-glucoside sugars under nitrogen limitation conditions. (A) Sucrose is a more potent inducer of pseudohyphal growth than glucose at both high (100 mM) and low (10 mM) concentrations, and the effects of both sugars are dependent on Gpr1. WT, wild type. (B) Maltose and maltotriose have potencies similar to that of sucrose for induction of pseudohyphal growth, but their effects are independent of Gpr1. (C) Addition of glucose and sucrose, but not maltose, to derepressed cells causes rapid induction of FLO11 in a Gpr1-dependent manner. The relative expression of FLO11 was measured over a 2-hour interval after sugar addition by real-time quantitative PCR analysis. A diploid wild-type strain and a gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ mutant were grown overnight to mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm, 2 to 4) on 2% glycerol. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (D) Induction of pseudohyphal growth by maltotriose, but not by sucrose or maltose, is deficient in a strain lacking the Agt1 (Mal11) transporter. Cells were grown for 24 h on nitrogen-limiting (SLA) medium supplemented with the indicated sugars. sucr, sucrose; malt, maltose; malt3ose, maltotriose. (E) A minimum level of cAMP is required for induction by alpha-glucoside sugars. A homozygous cyr1Δ yak1Δ pde2Δ mutant was grown on nitrogen-limiting medium (SLA) supplemented with 100 mM glucose, sucrose, maltose, or maltotriose. Intracellular cAMP concentrations were controlled by the addition of cAMP to the growth medium in the indicated concentrations. Pseudohyphal growth under these conditions was induced with external cAMP concentrations of 2 mM and higher. At all cAMP concentrations, sucrose and maltose were more potent inducers than glucose. Growth on maltotriose was reduced with increasing cAMP concentrations, and filamentation was limited.

Previous studies have suggested a role for the Gpr1-Gpa2 G-protein-coupled receptor sugar-sensing system that activates the cAMP-PKA pathway in the induction of dimorphic growth under nitrogen-limiting conditions (16, 18). Later, it was established that among a wide variety of sugars tested, only glucose and sucrose are true agonists of Gpr1-mediated cAMP signaling. As the affinity of Gpr1 for sucrose was shown to be about 40 times higher than for glucose (EC50s ≈ 0.5 mM and 20 mM, respectively) (12), we concentrated on the role of Gpr1 as a sucrose sensor in the induction of pseudohyphal growth. We show that only induction by sucrose and glucose of pseudohyphal growth in the microcolonies is dependent on Gpr1 (Fig. 1A). Induction by maltose (18) (Fig. 1B) and maltotriose (Fig. 1B) is Gpr1 independent.

The induction of the pseudohyphal growth phenotype is known to be dependent on the cell surface flocculin Flo11 (14). We therefore measured FLO11 expression in glycerol-grown diploid yeast cells shifted from a derepressed to a repressed state by stimulation with glucose, sucrose, or maltose. Figure 1C shows that sucrose causes the strongest induction of FLO11 expression. The induction of FLO11 observed after the addition of glucose or sucrose was entirely dependent on Gpr1, which correlates well with the increase in cAMP concentration observed after stimulation of derepressed cells with these sugars (12). Maltose, while a strong inducer of pseudohyphal growth on nitrogen-limiting medium, is not an agonist of Gpr1 and is not capable of inducing a rapid increase in FLO11 expression. This suggests the absence of a rapid receptor-mediated signaling mechanism for the induction of filamentation by maltose. As an alternative to receptor-mediated signal transduction, we investigated the requirement for alpha-glucoside transport in pseudohyphal growth induction. We found that pseudohyphal growth on maltotriose, but not on maltose or sucrose, was abolished in an agt1Δ/agt1Δ mutant, which lacked the broad-specificity alpha-glucoside transporter required for maltotriose uptake in yeast (Fig. 1D).

Why do sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose stimulate filamentation under nitrogen starvation conditions to similar extents, as only sucrose was shown to be a direct inducer of cAMP-PKA signaling? To address this question, we hypothesized that a parallel signaling mechanism could be operative in the induction of pseudohyphal growth on alternative carbon sources. The presence of an additional signaling mechanism was also suggested by a significant residual filamentation pattern in a gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ mutant growing under nitrogen limitation conditions on sucrose (Fig. 1A, B, and D and 2B). Although a number of filaments still projected from the colony in a gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ mutant growing on sucrose, the fraction of pseudohyphae consisting of elongated, unipolarly budding cells was always smaller in a gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ mutant than in the wild type. The well-established intrinsic variability of pseudohyphal growth in yeast generated somewhat different filamentation patterns in different experiments. However, the relative induction of filamentation on glucose and sucrose was always higher in the wild type than in the gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ mutant in the same experiment (compare growth on sucrose in Fig. 1B and 2B). We examined the possibility of an additional signaling mechanism by constructing a diploid homozygous cyr1Δ yak1Δ pde2Δ mutant in which PKA activity could be controlled independently of the carbon source by addition of extracellular cAMP. This mutant showed pseudohyphal differentiation only when enough cAMP was added to the medium (Fig. 1E). Surprisingly, sucrose and maltose still proved to be more potent inducers of filamentation than glucose in the presence of permissive cAMP concentrations. In addition, the threshold concentrations of cAMP for the induction of filamentation were not significantly different for the three sugars, indicating that sucrose or maltose does not increase the sensitivity of the cells to cAMP (Fig. 1E). Addition of cAMP inhibited growth on maltotriose and to a lesser extent on maltose. Several key genes required for the utilization of maltose and maltotriose are strongly repressed by glucose. As glucose-responsive genes were recently shown to be redundantly regulated by PKA-dependent and PKA-independent signaling mechanisms (21), we speculate that this repression is mimicked by the addition of cAMP to the medium in the absence of glucose. Induction of pseudohyphal growth by glucose in the homozygous cyr1Δ yak1Δ pde2Δ mutant was also dependent on cAMP, but at all cAMP concentrations, filamentation was weaker than that observed with the alpha-glucoside sugars. This indicates that an additional Gpr1-independent pathway is responsible for the difference between glucose and the alpha-glucoside sugars.

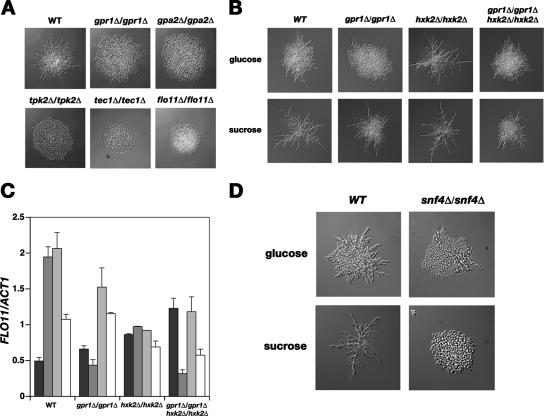

FIG. 2.

Induction of pseudohyphal growth in nitrogen limitation medium by sucrose requires cAMP-PKA-, MAP kinase-, and Snf1-mediated signaling. (A) Induction of pseudohyphal growth by 100 mM sucrose is deficient in mutants of the cAMP-PKA pathway, in a flo11Δ mutant, and in a mutant in which the gene encoding Tec1, a filamentation-specific transcription factor under the control of the MAP kinase pathway, was deleted. WT, wild type. (B) In a strain with HXK2 deleted, pseudohyphal growth was induced by 100 mM glucose to an extent similar to that with 100 mM sucrose. The presence of Gpr1 remained important for filamentation in the hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant. (C) FLO11 expression level. Sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose are better inducers than glucose of FLO11 expression in a wild-type strain. Induction by sucrose, but not by maltose and maltotriose, was dependent on Gpr1. In a hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant, all sugars induced the same relative level of FLO11 expression. Gene expression was monitored 4 h after induction with 100 mM of the indicated sugars by real-time quantitative PCR. Bars shaded progressively from black to white represent induction by glucose, sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose, respectively. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (D) Pseudohyphal growth induction by 100 mM glucose and sucrose was absent in a snf4Δ/snf4Δ mutant. The snf4Δ/snf4Δ mutant was grown for 48 h on sucrose.

PKA- and Snf1-mediated signaling control filamentation on glucose and alpha-glucoside sugars.

The observation that sucrose and maltose were more potent inducers of filamentation than glucose under conditions in which PKA activity is controlled in a carbon source-independent manner prompted us to investigate the possibility of a parallel signaling mechanism involved in pseudohyphal growth induction on these sugars. We first investigated whether the induction of pseudohyphal growth by sucrose is entirely dependent on the known pathways that control filamentation. Figure 2A shows that mutant strains in which components of the cAMP-PKA pathway or downstream factors involved in filamentation were deleted are defective in pseudohyphal growth on sucrose. Hence, the established signaling mechanisms required for the induction of pseudohyphal growth on glucose are also essential for filamentation on sucrose.

As glucose also seemed to repress filament formation in the cyr1Δ yak1Δ pde2Δ mutant, we reasoned that the differences in filamentation on different carbon sources could be mediated by Snf1-dependent signaling. It was previously shown that the sugar starvation sensor Snf1 regulates FLO11-dependent processes (11). In the case of pseudohyphal growth, Snf1 was more recently shown to respond to nitrogen limitation in a TOR-dependent manner (19). During growth on alpha-glucoside sugars, we expected higher Snf1 activity, as many genes required for their uptake and metabolization, such as the SUC2 and MAL genes, are strongly repressed by glucose. Thus, for control of pseudohyphal growth, Snf1 may serve its established role as a glucose deprivation sensor, as well. To evaluate a possible role of glucose repression in filamentation, we deleted the gene encoding hexokinase 2, which plays an important role in the repression of Snf1 activity by glucose. We observed an increase in filamentation in a hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant, in which glucose-induced inactivation of Snf1 activity was relieved and in which a strong defect in glucose repression occurred (9, 22). Figure 2B shows that in the hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant, filamentation on glucose increased to the same level as observed with sucrose. In addition, the hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant did not show hyperfilamentation on sucrose, indicating a specific link between Hxk2 and the repression of filamentation by glucose. A filamentation defect could be observed on both glucose and sucrose in a gpr1Δ/gpr1Δ hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant, underscoring the role of Gpr1 in the sensing of both sugars. The effects of GPR1 and HXK2 deletion on pseudohyphal differentiation could be correlated with expression analysis of the FLO11 gene (Fig. 2C). Sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose were better inducers than glucose of FLO11 expression in a wild-type strain. In the hxk2Δ/hxk2Δ mutant, FLO11 expression was basically the same on all sugars. Deletion of Gpr1 had the most dramatic effect on FLO11 expression during growth on sucrose, where it caused a strong reduction. On glucose, maltose, and maltotriose, there was no such clear effect. We further confirmed a role for Snf1 activity in the induction of pseudohyphal differentiation by deleting its activating γ subunit, Snf4. In an snf4Δ/snf4Δ mutant, filamentation was entirely absent on sucrose, indicating a key role of Snf1 activity for the induction of pseudohyphal growth on sucrose (Fig. 2D). The snf4Δ/snf4Δ mutant was unable to grow on maltose and maltotriose.

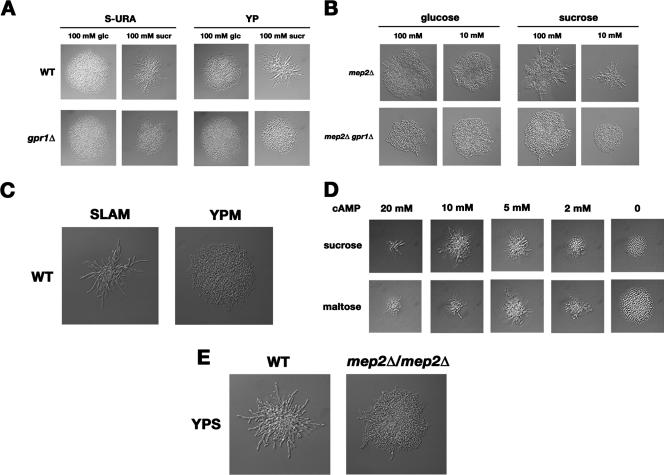

Gpr1 mediates induction of filamentation under nonstarvation conditions and in the absence of the ammonium permease Mep2.

Since alpha-glucosides are capable of inducing filamentation in a mutant deficient in cAMP synthesis, what could be the additional function of cAMP signaling by sucrose? It was previously reported that the addition of exogenous cAMP or the expression of gain-of-function Gpa2 or Ras2 mutant alleles could rescue filamentation in a mep2Δ/mep2Δ mutant. The precise connection between Mep2 and the cAMP-PKA pathway, however, remains unknown. In addition, recent work has shown that Mep2 might be required only for the reuptake of secreted ammonium, rather than acting as a low-ammonium sensor protein itself for induction of pseudohyphal growth through the PKA pathway or another signaling pathway (3). Since Gpr1 is a high-affinity sucrose sensor, we reasoned that the receptor might induce filamentation on sucrose by activating the cAMP-PKA pathway under conditions that were previously described as nonpermissive for filamentation. Indeed, we found that sucrose could induce pseudohyphal growth on nitrogen-rich growth media and also in a mep2Δ/mep2Δ mutant and that this induction was dependent on the expression of Gpr1 (Fig. 3A and B). Maltose, on the other hand, while a potent inducer of filamentation on nitrogen-limiting medium, is unable to induce pseudohyphal growth on nitrogen-rich media (Fig. 3C), which fits with the inability of maltose to activate Gpr1. To test whether the induction of pseudohyphal growth by sucrose on nitrogen-rich medium was dependent on cAMP, we measured filamentation in the cyr1Δ yak1Δ pde2Δ mutant in the presence of different external cAMP concentrations. Figure 3D shows that external cAMP was able to induce filamentation in this mutant on rich medium with both sucrose and maltose, and to similar extents. Thus, the induction of cAMP signaling through activation of Gpr1 seems to be the distinguishing feature allowing filamentous growth on sucrose but not on maltose in nitrogen-rich growth media.

FIG. 3.

Pseudohyphal growth induction on sucrose in nitrogen-rich medium and in the mep2Δ/mep2Δ mutant. (A) Sucrose induces pseudohyphal growth in nitrogen-rich medium, and this effect is dependent on Gpr1. Cells were grown overnight on minimal drop-out medium (S-URA) containing 5 g/liter ammonium sulfate or on complex YP medium. WT, wild type. (B) Sucrose (sucr), as opposed to glucose (glc), induced pseudohyphal growth in the mep2Δ/mep2Δ strain on nitrogen limitation medium, and this effect was dependent on Gpr1. (C) Maltose does not induce pseudohyphal growth on complex YP medium (YPM). SLAM, nitrogen limitation medium with maltose. (D) Sucrose and maltose are equally potent inducers of pseudohyphal growth on nitrogen-rich medium when the cells are provided with the same cAMP level. A homozygous cyr1Δ yak1Δ pde2Δ mutant was grown on nitrogen-rich minimal drop-out medium (S-URA) supplemented with sucrose or maltose for 24 h. Intracellular cAMP concentrations were controlled by the addition of extracellular cAMP as indicated. (E) Pseudohyphal growth was induced by 100 mM sucrose on nitrogen-rich complex medium (YPS) in a wild-type strain, but not in a mep2Δ/mep2Δ mutant.

The identification of a carbon source that is able to induce pseudohyphal growth on rich media where ammonium is abundantly present enabled us to reevaluate the role of Mep2 in the induction of filamentous growth. Previously, Mep2 was proposed to act as an ammonium starvation sensor, as it was shown to be required for filamentation under nitrogen-limiting conditions on glucose (17). If Mep2 is an ammonium starvation sensor, filamentation on ammonium-rich medium with sucrose is expected to be independent of Mep2. Figure 3E, however, shows that Mep2 expression is indispensable for induction of pseudohyphal growth on ammonium-rich medium. Thus, in this case, Mep2 might act as a bona fide ammonium sensor, signaling the presence of ammonium to PKA and thereby inducing filamentation. Alternatively, it might also be required for the uptake of ammonium from the medium, although in the presence of high external ammonium one would expect ammonium uptake through Mep1 and Mep3 to be sufficient, especially since sucrose induces filamentation in the mep2Δ/mep2Δ mutant on ammonium-limiting medium. The sensitivity of Mep2 for rapid induction of the PKA pathway by addition of ammonium to nitrogen-starved cells was shown to be very high (EC50 = 2 μM) (20). This might explain why Mep2 could still fulfill its role as an ammonium sensor on ammonium-limiting medium, which contains only 50 μM of ammonium. It was recently shown that high ammonium levels repress genes involved in the production of secreted aromatic alcohols, which are known to induce filamentation in yeast (4). The upstream ammonium-sensing mechanism that mediates the repression of these genes in response to nitrogen availability remains to be identified.

By observing filamentation in microcolonies, we showed that the fraction of cells in a colony displaying pseudohyphal growth especially is strongly increased during growth on alpha-glucoside sugars compared to glucose. The number of cells showing an elongated morphology and a unipolar budding pattern in a colony was found to be dependent on cAMP-PKA- and Snf1-dependent signaling. As the frequency of pseudohyphae in a colony is known to reflect the desilenced state of FLO11 (8), the induction of filamentation in the presence of an appropriate carbon source may be a prime in vivo function of the established histone H3 kinase activity of Snf1, which is also involved in other silencing-related processes, such as INO1 expression and ageing (2, 13, 15). We found that glucose is a poor inducer of filamentation compared to sucrose and other oligomeric alpha-glucoside sugars. Previous reports have suggested a link between Snf1 activity and diploid pseudohyphal growth through inhibition of the repressor proteins Nrg1 and Nrg2. However, as pseudohyphal growth is commonly monitored under nitrogen starvation conditions in the presence of high glucose levels, the requirement for Snf1 activity has been related to the sensing of nitrogen starvation rather than glucose signaling (11, 19). We have shown that Snf1 plays its established role as a glucose deprivation sensor during pseudohyphal growth on alternative carbon sources.

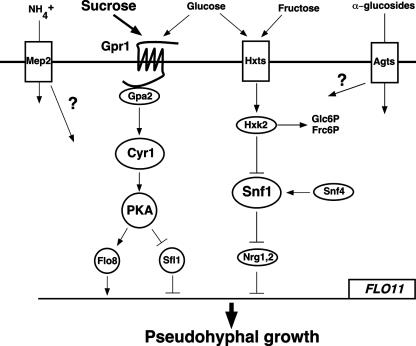

This study reveals how activation of the cAMP-PKA and the glucose repression pathways underlies the difference in potency between glucose and alpha-glucoside sugars for inducing diploid filamentous growth in yeast. We further investigated the preeminent role of sucrose as a nutrient inducer able to trigger filamentation in nitrogen-rich medium and in the mep2Δ/mep2Δ mutant on ammonium-limiting medium. We demonstrated that cAMP signaling through Gpr1 is responsible for the induction of pseudohyphal growth on nitrogen-rich media in the presence of sucrose and for the difference in filamentation potencies between sucrose and maltose in these media. An important role of Gpr1-mediated cAMP signaling might be to overrule the partial activation of the glucose repression pathway by the extracellular hydrolysis of sucrose to glucose and fructose catalyzed by periplasmic invertase (Suc2). A simplified scheme depicting the signaling mechanisms involved in the sensing of different carbon sources is shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Simplified scheme depicting the sensing and signaling components involved in the induction of pseudohyphal growth by hexose (glucose and fructose) and alpha-glucoside sugars (sucrose, maltose, and maltotriose). Glucose and sucrose activate PKA through Gpr1, Gpa2, and adenylate cyclase (Cyr1), leading to the induction of FLO11 transcription by controlling the activities of transcription regulators, such as Flo8 and Sfl1. Monomeric hexose sugars inhibit pseudohyphal growth by inactivating the Snf1 kinase upon uptake by hexose transporters (Hxts) and phosphorylation by hexokinase 2 (Hxk2). Snf1 is known to induce filamentation by inactivating the repressor proteins Nrg1 and Nrg2 and is itself activated by its γ subunit, Snf4. Maltotriose and possibly other alpha-glucoside sugars activate pseudohyphal growth upon or after transport across the plasma membrane by alpha-glucoside transporters (Agts). The ammonium permease Mep2 is required for pseudohyphal growth in the presence of ammonium, but how it links to the other pathways is unclear.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Institute for Scientific and Technological Research (IWT) and a postdoctoral fellowship (PDM) from the KULeuven Research Fund to S.V.D.V. and by grants from the Fund for Scientific Research—Flanders, the KULeuven Research Fund (Concerted Research Actions), and Interuniversity Attraction Poles Network P6/14 to J.M.T.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amberg, D. C., D. J. Burke, and J. N. Strathern. 2005. Methods in yeast genetics: a Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 2.Ashrafi, K., S. S. Lin, J. K. Manchester, and J. I. Gordon. 2000. Sip2p and its partner snf1p kinase affect aging in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 141872-1885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeckstaens, M., B. Andre, and A. M. Marini. 2007. The yeast ammonium transport protein Mep2 and its positive regulator, the Npr1 kinase, play an important role in normal and pseudohyphal growth on various nitrogen media through retrieval of excreted ammonium. Mol. Microbiol. 64534-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, H., and G. R. Fink. 2006. Feedback control of morphogenesis in fungi by aromatic alcohols. Genes Dev. 201150-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gancedo, J. M. 2001. Control of pseudohyphae formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25107-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gietz, R. D., and A. Sugino. 1988. New yeast Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene 74527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gimeno, C. J., P. O. Ljungdahl, C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 681077-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halme, A., S. Bumgarner, C. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 2004. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of the FLO gene family generates cell-surface variation in yeast. Cell 116405-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang, R., and M. Carlson. 1996. Glucose regulates protein interactions within the yeast SNF1 protein kinase complex. Genes Dev. 103105-3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraakman, L., K. Lemaire, P. Ma, A. W. R. H. Teunissen, M. C. V. Donaton, P. Van Dijck, J. Winderickx, J. H. de Winde, and J. M. Thevelein. 1999. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae G-protein coupled receptor, Gpr1, is specifically required for glucose activation of the cAMP pathway during the transition to growth on glucose. Mol. Microbiol. 321002-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuchin, S., V. K. Vyas, and M. Carlson. 2002. Snf1 protein kinase and the repressors Nrg1 and Nrg2 regulate FLO11, haploid invasive growth, and diploid pseudohyphal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 223994-4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemaire, K., S. Van de Velde, P. Van Dijck, and J. M. Thevelein. 2004. Glucose and sucrose act as agonist and mannose as antagonist ligands of the G-protein coupled receptor Gpr1 in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 16293-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, S. S., J. K. Manchester, and J. I. Gordon. 2003. Sip2, an N-myristoylated beta subunit of Snf1 kinase, regulates aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by affecting cellular histone kinase activity, recombination at rDNA loci, and silencing. J. Biol. Chem. 27813390-13397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo, W. S., and A. M. Dranginis. 1996. FLO11, a yeast gene related to the STA genes, encodes a novel cell surface flocculin. J. Bacteriol. 1787144-7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo, W. S., L. Duggan, N. C. Emre, R. Belotserkovskya, W. S. Lane, R. Shiekhattar, and S. L. Berger. 2001. Snf1—a histone kinase that works in concert with the histone acetyltransferase Gcn5 to regulate transcription. Science. 2931142-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1997. Yeast pseudohyphal growth is regulated by GPA2, a G protein α homolog. EMBO J. 167008-7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1998. The MEP2 ammonium permease regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 171236-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorenz, M. C., X. Pan, T. Harashima, M. E. Cardenas, Y. Xue, J. P. Hirsch, and J. Heitman. 2000. The G protein-coupled receptor Gpr1 is a nutrient sensor that regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 154609-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orlova, M., E. Kanter, D. Krakovich, and S. Kuchin. 2006. Nitrogen availability and TOR regulate the Snf1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell. 51831-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Nuland, A., P. Vandormael, M. Donaton, M. Alenquer, A. Lourenco, E. Quintino, M. Versele, and J. M. Thevelein. 2006. Ammonium permease-based sensing mechanism for rapid ammonium activation of the protein kinase A pathway in yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 591485-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, Y., M. Pierce, L. Schneper, C. G. Guldal, X. Zhang, S. Tavazoie, and J. R. Broach. 2004. Ras and Gpa2 mediate one branch of a redundant glucose signaling pathway in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmermann, F. K., and I. Scheel. 1977. Mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae resistant to carbon catabolite repression. Mol. Gen. Genet. 15475-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]