Abstract

It is well-known that micromolar to millimolar concentrations of cardiac glycosides inhibit Na/K pump activity, however, some early reports suggested nanomolar concentrations of these glycosides stimulate activity. These early reports were based on indirect measurements in multicellular preparations, hence, there was some uncertainty whether ion accumulation/depletion rather than pump stimulation caused the observations. Here, we utilize the whole-cell patch-clamp technique on isolated cardiac myocytes to directly measure Na/K pump current (IP) in conditions that minimize the possibility of ion accumulation/depletion causing the observed effects. In guinea pig ventricular myocytes, nanomolar concentrations of dihydro-ouabain (DHO) caused an outward current that appeared to be due to stimulation of IP because of the following: (1) it was absent in 0 mM [K+]o, as was IP; (2) it was absent in 0 mM [Na+]i, as was IP; (3) at reduced [Na+]i, the outward current was reduced in proportion to the reduction in IP; (4) it was eliminated by intracellular vanadate, as was IP. Our previous work suggested guinea pig ventricular myocytes coexpress the α1- and α2-isoforms of the Na/K pumps. The stimulation of IP appears to be through stimulation of the high glycoside affinity α2-isoform and not the α1-isoform because of the following: (1) regulatory signals that specifically increased activity of the α2-isoform increased the amplitude of the stimulation; (2) regulatory signals that specifically altered the activity of the α1-isoform did not affect the stimulation; (3) changes in [K+]o that affected activity of the α1-isoform, but not the α2-isoform, did not affect the stimulation; (4) myocytes from one group of guinea pigs expressed the α1-isoform but not the α2-isoform, and these myocytes did not show the stimulation. At 10 nM DHO, total IP increased by 35 ± 10% (mean ± SD, n = 18). If one accepts the hypothesis that this increase is due to stimulation of just the α2-isoform, then activity of the α2-isoform increased by 107 ± 30%. In the guinea pig myocytes, nanomolar ouabain as well as DHO stimulated the α2-isoform, but both the stimulatory and inhibitory concentrations of ouabain were ∼10-fold lower than those for DHO. Stimulation of IP by nanomolar DHO was observed in canine atrial and ventricular myocytes, which express the α1- and α3-isoforms of the Na/K pumps, suggesting the other high glycoside affinity isoform (the α3-isoform) also was stimulated by nanomolar concentrations of DHO. Human atrial and ventricular myocytes express all three isoforms, but isoform affinity for glycosides is too similar to separate their activity. Nevertheless, nanomolar DHO caused a stimulation of IP that was very similar to that seen in other species. Thus, in all species studied, nanomolar DHO caused stimulation of IP, and where the contributions of the high glycoside affinity α2- and α3-isoforms could be separated from that of the α1-isoform, it was only the high glycoside affinity isoform that was stimulated. These observations support early reports that nanomolar concentrations of glycosides stimulate Na/K pump activity, and suggest a novel mechanism of isoform-specific regulation of IP in heart by nanomolar concentrations of endogenous ouabain-like molecules.

Keywords: cardiac electrophysiology, Na/K ATPase, cardiac glycosides

INTRODUCTION

The Na/K pump utilizes the energy stored in one ATP molecule to translocate three Na+ out of the cell and two K+ into the cell. Thus, the cycle generates a net outward current that tends to hyperpolarize the membrane voltage. Each Na/K pump comprises an α and a β subunit, however, the α subunit alone binds Na+ and K+ and possesses the ATPase activity. Three different isoforms (α1, α2, and α3) of the α subunit are widely expressed in an organ-specific manner (Sweadner, 1989), and recently Woo et al. (1999) identified a fourth isoform in testes.

We have reported previously guinea pig ventricular myocytes express two functionally distinct Na/K pumps: one with a high affinity for inhibition by dihydro-ouabain (DHO;*1 μM DHO dissociation constant) and the other with a low affinity (100 μM DHO dissociation constant; Gao et al., 1995; for review see Mathias et al., 2000). This is consistent with the observations by others (Mogul et al., 1989; Berrebi-Bertrand et al., 1991). We also have reported that mRNA for the α1- and α2-isoforms of the Na/K ATPase coexist in guinea pig ventricular myocytes (Gao et al., 1999a). Given the relative amounts of mRNA were consistent with the high and low DHO affinity currents, and since in rodent heart the α2-isoform has a high affinity for ouabain (OUA) and the α1-isoform has a low affinity (Sweadner, 1989), the α2- and α1-isoforms most likely represent the high and low DHO affinity pumps, respectively.

Our studies on regulation of these two isoforms in guinea pig ventricular myocytes (reviewed in Mathias et al., 2000) showed that transport by the α2-isoform is increased by α-adrenergic activation but is unaffected by β-adrenergic activation. Conversely, transport by the α1-isoform is modulated by β-adrenergic activation, but is not affected by α-adrenergic activation. Gao et al. (1995) showed that half-maximal activation of the α2-isoform occurred at a [K+]o of 0.4 mM, a concentration ∼10-fold lower than that for the α1-isoform (4 mM [K+]o). Thus, in guinea pig myocytes, we have three markers that functionally separate the α1- and α2-isoforms: their affinity for DHO, their response to α- and β-adrenergic activation, and their response to changes in [K+]o.

Canine ventricular myocytes also have high and low DHO affinity Na/K pumps, but RNase protection assays indicate they express the α1-isoform and α3-isoform, which also has a high affinity for OUA (Maixent et al., 1987; Zahler et al., 1996). Insofar as we have looked, the α3-isoform in dog has the same functional properties as the α2-isoform in guinea pig, however, our studies in dog are not as extensive as in guinea pig.

All of the three α-isoforms (α1, α2, and α3) of the Na/K pump are present in human heart (Shamraj et al., 1991; Zahler et al., 1993). However in the human, the affinities of these isoforms for OUA are nearly identical (Shamraj et al., 1993). The Na/K pumps of human atrial cells appear to share some of the functional properties we have determined for the α2-isoform of the Na/K pump in guinea pig ventricle: they are stimulated by α-adrenergic activation, but are unaffected by β-adrenergic activation.

A number of studies have suggested that very low concentrations of cardiac glycosides can stimulate activity of the Na/K pumps in heart (for review see Noble, 1980). There also are reports of endogenous ouabain-like substances that are released at very low concentrations (Kolbel and Schreiber, 1996; Jortani and Valdes, 1997). This suggests the possibility of another isoform-specific regulatory input, coupled to endogenous ouabain-like substances. The purpose of the present study was to carefully characterize the effects of nanomolar [DHO] or [OUA] on the various isoforms of the Na/K pumps in heart cells from different species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Single cardiac myocytes were enzymatically isolated from adult male guinea pig hearts as previously described in Gao et al. (1992) or from mongrel dog hearts as described in Cohen et al. (1987). Guinea pigs, weighing 300–500 g, were killed with sodium pentobarbitone solution (1 ml of 390 mg ml−1) by peritoneal injection, and adult mongrel dogs were killed with the same euthanasia solution but by intravenous injection. Human heart tissues were provided by the Department of Surgery and isolated into single cells following the procedures described in Cohen et al. (1987). The human tissue was a byproduct of surgery and obtained in accordance with an approved protocol in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. The isolated cells were stored in KB solution (Isenberg and Klockner, 1982) containing the following (in mM): 83 KCl, 30 K2HPO4, 5 MgSO4, 5 sodium pyruvic acid, 5 β-OH-butyric acid, 5 creatine, 20 taurine, 10 glucose, 0.5 EGTA, 2 KOH, and 5 Na2-ATP, pH 7.2.

An Axopatch 1A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc.) and the whole-cell patch-clamp technique were used to observe cell membrane current. Patch pipette resistances were 1–3 MΩ before sealing. The pipette solution contained the following (in mM): 70 sodium aspartic acid, 20 potassium aspartic acid, 30 CsOH, 20 TEACl, 5 HEPES, 11 EGTA, 1 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 7 MgSO4, and 5 Na2-ATP, pH 7.2. In the Na+-free pipette solution, sodium aspartic acid was replaced with the free acid of aspartic acid. In the experiments to examine the effects of α- and β-adrenergic agonists on IP, 0.2 mM Na2-GTP was included in the pipette solution. The external Tyrode solution contained (mM) the following: 137.7 NaCl, 2.3 NaOH, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 5 HEPES, 2 BaCl2, and 1 CdCl2, pH 7.4. In K+-free Tyrode solution, KCl was deleted without ionic strength adjustment.

The heart cells were held at 0 mV after the formation of the whole-cell recording configuration. All experiments were conducted at 32 ± 0.5°C. External solutions containing various concentrations of DHO or ouabain (OUA) were superfused to observe changes in Na/K pump current (IP). Based on our earlier work (for review see Mathias et al., 2000), current generated by the α2-isoform is blocked with a dissociation constant of ∼1 μM DHO, whereas that generated by the α1-isoform is blocked with a dissociation constant of ∼100 μM DHO. Thus, 5 μM DHO blocks most of the current generated by the α2-isoform and almost none of the current generated by the α1-isoform, so this concentration of DHO was used to separately assay activity of the α2-isoform. Total Na/K pump activity due to the α1-isoform plus the α2-isoform was assayed as the current blocked by 1 mM DHO. 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO) plus 1 μM prazosin (PZ), or 10 μM norepinephrine (NE) plus 10 μM propranolol, were added to the external solution to study the effects of β- or α-adrenergic activation on IP, respectively. All patch-clamp data were recorded on disc by the data acquisition program AxoScope 1.1 (Axon Instruments, Inc.), for later analysis. The sampling rate was 200 ms/point, and the data were low pass filtered at 2 Hz. The paired t test was used to determine P values, with P < 0.05, indicating a significant difference between outcomes.

RNase protection assays were performed essentially as described previously (Gao et al., 1999a). For each experiment, 2 μg of total RNA was used. Cyclophilin probes were included in the hybridization reaction to confirm that the sample was not lost during the course of the experiment and to provide a standard for quantitative measurement of Na/K pump mRNA for each isoform. 5 μg of yeast tRNA was used as a negative control for probe self-protection bands. The RNase protection assay figures are all 4-d exposures. For the comparison of the α1- and α2-isoform mRNA levels in ventricle, the intensity of the specific protected signals were measured directly from RNase protection gels using a Phosphor Imager (Molecular Dynamics). In this experiment, three independent samples of RNA were used.

RESULTS

As described in the introduction, guinea pig ventricular myocytes coexpress the α1- and α2-isoforms of the Na/K pump (Gao et al., 1995). Since these two isoforms have an ∼100-fold difference in affinity for the cardiac glycosides, they can be studied separately by using 5 μM DHO to block the current generated by only the α2-isoform (IP2), and using 1 mM DHO to block total current (IP) generated by the both isoforms. Total pump current is given by IP = IP1 + IP2. With physiological pH and [K+]o, IP1 is ∼60% of IP, but there is some cell to cell variation in this percent. There also is considerable cell to cell variation in myocyte size as well as in the density of total pumps per square centimeter of cell membrane. The original records displayed in this section reflect the variability in all of these parameters, so a wide range of current scales are used to optimally display each individual record. However, when we studied an effector of pump current, the standard protocol was to measure pump current in control, test conditions in the same cell, and then calculate the ratio of test to control current and average this ratio from at least five cells. This procedure uses each cell as its own control and removes the uncertainty due to cell to cell variation in size and pump density. In the data that follow, when we report an effect on the pump current, that effect was relative to control conditions in the same cell, and each effect was observed in 100% of the cells in which the protocol was completed. This procedure requires that each cell be held stably in the whole-cell patch configuration for time periods in excess of 10 min. The human heart cell data shown in Fig. 10 C are the only exception to the above protocol. After patch clamping these cells, they generally survived only a few minutes. Therefore, we made a quick measurement of cell capacitance at the beginning of each experiment, and this was used as a measure of cell size to normalize the subsequent measurements of IP.

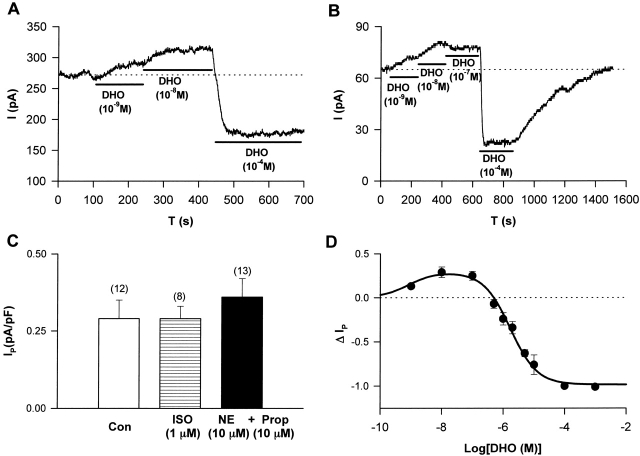

Figure 10.

The effects of DHO on Na/K pump current in human heart cells. Stimulation of IP by low [DHO] and inhibition of IP by high [DHO] were observed in human ventricular myocytes (A) and in human atrial myocytes (B). (C) The effects of β-adrenergic activation (ISO) and α-adrenergic activation (NE + PROP) on IP in human atrial cells. Bars indicate standard deviations. The numbers in the parentheses represent the number of cells studied. There was no significant effect of ISO (P = 0.50). However, there was a significant difference between IP in control and that in the presence of α-adrenergic activation (P = 0.009). (D) The ΔIP-DHO curve in human atrial cells. ΔIP was normalized as described in Fig. 6 A. Data were fitted assuming the presence of only one DHO affinity pump, since the α1-isoform of the Na/K pump in human heart has essentially the same DHO affinity as the α2- and α3-isoforms. The positive values of ΔIP at DHO concentrations of 10−9, 10−8, and 10−7 M represent statistically significant increases in the holding current with P values of 3 × 10−3, 10−3, and 4 × 10−3, respectively.

IP Is Stimulated by Nanomolar Concentrations of DHO in Guinea Pig Ventricular Myocytes

After whole-cell recording was initiated, a period of at least 5 min was required for the pipette and intracellular solutions to come to steady state (Gao et al., 1992). When steady state was achieved, different concentrations of DHO were superfused to observe the DHO-induced changes in holding current. In Fig. 1 A, when 5 μM DHO was applied rapidly, an inward shift in the holding current was observed, indicating inhibition of the current generated by the α2-isoform of the Na/K pumps (Gao et al., 1999a; for review see Mathias et al., 2000). Upon washout of DHO, the holding current returned to its original level. Our first indication that nanomolar DHO might stimulate IP was observed in the same cell, when 5 μM DHO was applied slowly. In this situation, the holding current experienced an initial outward transient (indicated by the arrow), which could not be attributed to any artifact, suggesting very low concentrations of DHO may stimulate the pumps. The same results were consistently observed in a total of eight cells, suggesting relatively low concentrations of DHO might have evoked the initial increase in holding current (i.e., as the solution containing 5 μM DHO was slowly perfused into the DHO-free bath, the initial [DHO] was much lower than 5 μM). Therefore, we used 10 nM DHO to investigate whether a steady state increase in outward current could be generated (Fig. 1 B). Upon washout of DHO, the holding current returned to its original level. However, when the external K+ was removed, 10 nM DHO did not induce any change in the holding current in the same cell. The same results were observed in a total of six cells, suggesting that the steady state increase in outward current by 10 nM DHO at 5.4 mM [K+]o could be due to stimulation of IP.

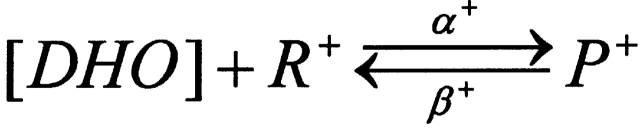

Figure 1.

Stimulation of IP in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. (A) Slow superfusion of solution containing 5 μM DHO caused the bath concentration of DHO to slowly rise from 0 to 5 μM. This induced an initial outward transient in holding current (arrow) followed by the inward shift. The outward transient was not observed when 5 μM DHO was rapidly superfused. See results for details. (B) The steady state increase in outward holding current induced by 10 nM DHO in the presence of 5.4 mM [K+]o did not occur when the external K+ was removed, suggesting the outward shift in current was due to stimulation of IP. (C) Stimulation of IP was intracellular Na+-dependent. (top) Intracellular Na+ was completely removed after waiting 6 min in the whole-cell mode with a pipette resistance (RP) of 1.5 MΩ. Neither the outward shift in current at 10 nM DHO nor inhibition of IP by 1 mM DHO was observed. (middle) In a second experiment, a small amount of Na+ remained in the cell after waiting only 5 min with RP of 4 MΩ. A small shift in outward current at 10 nM DHO and a small inhibition of IP by 1 mM DHO were observed. (bottom) In a third experiment, a larger amount of Na+ remained in the cell after waiting 4 min with RP of 5 MΩ. A larger outward shift in current and a larger blockade of IP were observed. Thus, the outward shift in current at 10 nM DHO and blockade of IP at 1 mM DHO were highly correlated, providing further evidence that the outward current was due to stimulation of IP. (D) Intracellular vanadate blocks both IP and the low DHO-dependent outward current. (left) When 1 mM sodium orthovanadate was included in the pipette solution, 10 nM DHO did not cause an outward shift in current and 1 mM DHO did not cause an inward shift in current, indicating inhibition of total IP also inhibited the low DHO stimulation of IP. (right) Cells isolated from ventricles of the same heart show a typical stimulation and inhibition of IP by low and high [DHO], respectively, when vanadate was not in the pipette solution.

The Na/K pump also requires intracellular Na+ for transport to take place. If the DHO effect is stimulation of IP, then, if intracellular Na+ were removed, the 10 nM DHO-induced outward current should not occur. Therefore, we removed all Na+ from the pipette solution and observed the effect of 10 nM DHO on the holding current. In the top panel of Fig. 1 C, the patch pipette resistance was 1.5 MΩ, and the waiting period for the pipette and the intracellular solutions to come to steady state was 6 min. The application of 10 nM DHO did not induce any change in the holding current. A second exposure to a saturating concentration of 1 mM DHO (Gao et al., 1995) in the same cell also had no effect, indicating the Na/K pump current was eliminated by the removal of intracellular Na+. In a different cell, the pipette resistance was higher at 4 MΩ, and the waiting period before the application of 10 nM DHO was shorter at 5 min. Based on the data and analysis in Oliva et al. (1988), in this period of time, given this pipette resistance, some residual [Na+]i should have been present. The same protocol as described above was applied. A relatively small outward shift in current by 10 nM DHO and a small inward shift by 1 mM DHO were observed, indicating a small amount of intracellular Na+ remained due to the higher resistance pipette and shorter waiting period. The remaining Na+ presumably activates a small fraction of total Na/K pump current. Therefore, the low [DHO] stimulation and the high [DHO] inhibition were present but smaller than normal (Fig. 1 C, middle). In another cell, the pipette resistance was 5 MΩ, and the waiting period was 4 min. A higher [Na+]i should have remained, due to the further increase in pipette resistance and decrease in waiting period. Therefore, a larger stimulation of IP and a larger IP blockade should be induced by low [DHO] and high [DHO], respectively, as shown in Fig. 1 C (bottom). In each experiment, the outward current shift (stimulation of IP) by 10 nM DHO was about a third of the total IP, supporting the hypothesis that the outward current evoked by low [DHO] is stimulation of IP.

The application of vanadate inside of a cell has several effects (Akera et al., 1979; Takeda et al., 1980; Fox et al., 1983), including blockade of Na/K ATPase activity. Since we assay for IP by recording the change in current elicited by external DHO, a specific inhibitor of IP, we can separate the effects of vanadate on IP from other effects. We included 1 mM sodium orthovanadate in the pipette solution to completely inhibit the Na/K pumps, and then performed a similar protocol to that described in Fig. 1 C. Fig. 1 D (left) shows that application of 10 nM DHO did not induce an increase in outward current, and 1 mM DHO did not inhibit any pump current. To ensure that this was not due to a change in affinity for DHO, 2 mM DHO was applied, but IP was still not detectable. Similar results were observed in a total of five cells, suggesting that when IP was completely inhibited, low [DHO] could not induce the increase in outward current. However, in the absence of vanadate, the stimulation of IP by low [DHO] and the inhibition of IP by high [DHO] were observed in cells isolated from the same guinea pig hearts. Fig. 1 D (right) shows a holding current recording in the absence of vanadate. In this cell, the increase in outward current induced by 10 nM DHO was 24 pA, and IP inhibited by 1 mM DHO was 88 pA. Similar results were obtained in a total of five cells, thus, when IP was not blocked, the increase in outward current was observed. All of the results shown in Fig. 1 are consistent with the hypothesis that the low [DHO]-induced increase in outward current is due to stimulation of IP.

Stimulation of IP by Nanomolar [DHO] Is Associated with the α2-Isoform and Not the α1-Isoform of the Na/K Pumps in Guinea Pig Ventricular Myocytes

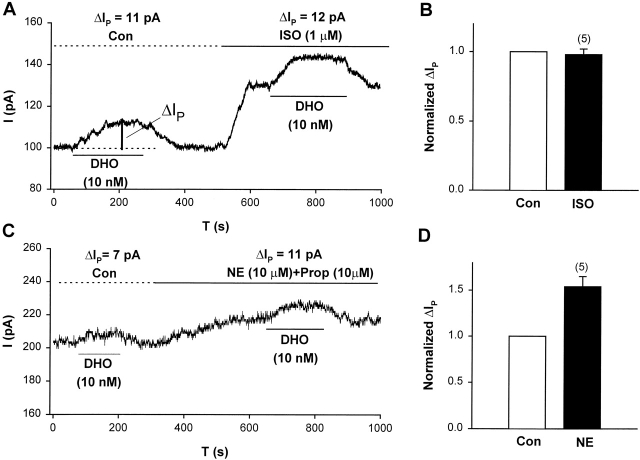

We have shown previously that β-adrenergic activation, through activation of PKA, specifically increases the current generated by the α1-isoform (for review see Mathias et al., 2000), either by increasing the number of pumps in the plasma membrane or by increasing the turnover rate of each pump. In either situation, if the stimulation of IP by nanomolar [DHO] is via the α1-isoform, the stimulation should increase in the presence of β-adrenergic activation. We examined the effects of β-adrenergic activation with the specific β-agonist isoproterenol (ISO). Fig. 2 A shows the effect of ISO on the stimulation of IP by 10 nM DHO. In this example, stimulation of IP in the control solution (IP(Con)) and that in the presence of ISO (IP(ISO)) are 11 and 12 pA, respectively. The summary of the results from a total of five cells is shown in Fig. 2 B. The stimulation of IP(Con) was normalized to 1. Then, the ratio IP(ISO)/IP(Con) in each cell was averaged to obtain the value 0.98 ± 0.04 (SD), indicating ISO had no effect on the stimulation of IP, suggesting the α1-isoform is not involved.

Figure 2.

Adrenergic modulation of IP in guinea pig ventricular myocytes suggests the α2-isoform and not the α1-isoform is involved in stimulation of IP by low [DHO]. (A) A typical record of holding current in an experiment showing the effect of β-adrenergic activation with ISO on stimulation of IP by 10 nM DHO. The vertical bar labeled with ΔIP indicates the magnitude of the stimulation of IP. The large increase in holding current in the presence of ISO is mainly due to the activation of the Cl− conductance (Harvey and Hume, 1989; Bahinski et al., 1989). (B) Summary of the results from a total of five cells. ΔIP was normalized by its value in control conditions. The normalized ΔIP in the presence of ISO was 0.98 ± 0.04 (SD), suggesting that ISO had no effect on the stimulation (P = 0.51). (C) A typical record of holding current in an experiment showing the effect of α-adrenergic activation (NE and PROP) on ΔIP. (D) Summary of the results from a total of five cells. The normalized ΔIP in the presence of α-activation was 1.54 ± 0.11 (SD), suggesting that α activation enhanced the stimulation of IP (P = 0.008).

We have also shown previously that α-adrenergic activation, through activation of PKC, specifically increases the current generated by the α2-isoform (for review see Mathias et al., 2000), again either by increasing the number of pumps in the plasma membrane or by increasing the turn-over rate of each pump. In either situation, if the stimulation of IP is via the α2-isoform, α-adrenergic activation should increase it. We examined the effects of α-adrenergic activation with norepinephrine (NE) in the presence of the β-blocker propranolol (PROP). Fig. 2 C shows the effect of α-adrenergic activation on the stimulation of IP. In this cell, the stimulation of IP in control and that in the presence of NE + PROP are 7 and 11 pA, respectively. Fig. 2 D summarizes the results from a total of five cells. The stimulation of IP in control was normalized to 1; in each cell, the ratio of the stimulation of IP in the presence of NE + PROP to that in control was averaged to obtain the value 1.54 ± 0.11 (SD). Hence α-adrenergic activation increased the stimulation of IP by nanomolar [DHO] but β-adrenergic activation had no effect. Based on our previous studies (Gao et al., 1999a; for review see Mathias et al., 2000), these results suggest that the stimulation of IP by nanomolar [DHO] involves the α2-isoform but not the α1-isoform of the Na/K pump.

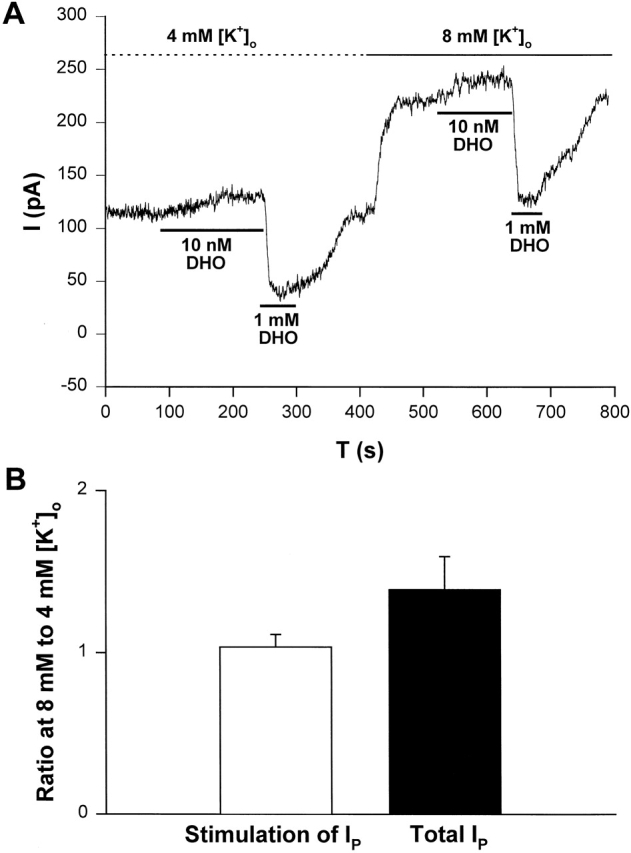

Gao et al. (1995) showed that the [K+]o affinity of the α2-isoform is much higher (K1/2 = 0.4 mM) than that of the α1-isoform (K1/2 = 4 mM). Thus at 4 mM [K+]o, α2-isoform activity is at 0.92 of saturation, whereas α1-isoform is at half-saturation. Hence, if [K+]o is changed from 4 to 8 mM, α1-isoform activity will increase significantly, whereas α2-isoform activity will increase very little. If the stimulation of IP by nanomolar [DHO] is not via the α1-isoform, then changing [K+]o from 4 to 8 mM will not change the stimulation of IP very much, but it will increase total IP by increasing α1-isoform activity. Therefore, two predictions emerge: (1) in each cell, the ratio of the stimulation of IP in 8 to 4 mM [K+]o will be ∼1.04, given the average numbers presented in Gao et al. (1995); (2) in each cell, the ratio of total IP in 8 to 4 mM [K+]o will be ∼1.4, again based on average numbers presented in Gao et al., 1995. Fig. 3 A shows an example of the protocol. In this cell, at 4 mM [K+]o the stimulation of IP by 10 nM DHO was 26 pA, and the total IP indicated by 1 mM DHO was 71 pA. In the same cell when the external solution contained 8 mM [K+]o, the stimulation of IP was 27 pA and total IP indicated by 1 mM DHO was 96 pA. Thus, the ratio of the stimulation at 8 to 4 mM [K+]o was 1.04, whereas the ratio of total IP in 8 to 4 mM [K+]o was 1.35. Fig. 3 B summarizes the results from a total of five cells. The ratio of IP stimulation in 8 to 4 mM [K+]o was 1.04 ± 0.08, and the ratio of total IP increased in all cells by an average value of 1.39 ± 0.20. These results are consistent with the predictions and further support the hypothesis that stimulation of IP is not associated with the α1-isoform of the Na/K ATPase.

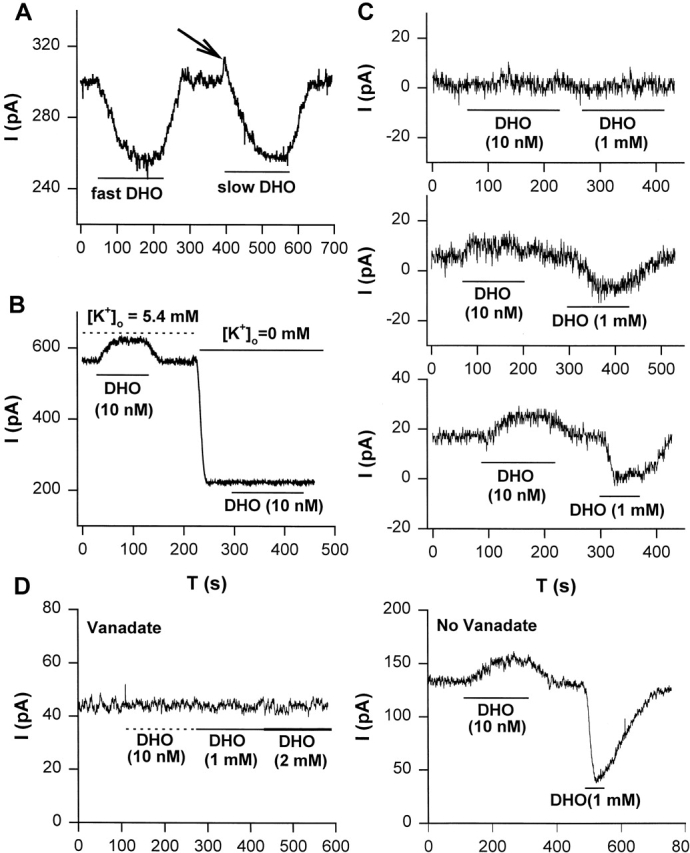

Figure 3.

[K+]o modulation of IP in guinea pig ventricular myocytes suggests the α2-isoform and not the α1-isoform is involved in stimulation of IP by low [DHO]. (A) An original record of holding current showing the protocol for observing stimulation of IP by low [DHO] and inhibition of IP by high [DHO] in 4 and 8 mM [K+]o. In this cell, when [K+]o was 4 mM, the stimulation of IP was 26 pA and the inhibition was 71 pA. When [K+]o was increased to 8 mM, the stimulation of IP was 27 pA and the inhibition was 96 pA. Thus activity of the α1-isoform increased, but the stimulation did not. (B) Average results from five cells. In each cell, the stimulation by 10 nM DHO and the inhibition by 1 mM DHO were recorded in 4 and 8 mM [K+]o, and then the ratio of the stimulation of IP (1.04 ± 0.08, P = 0.31) at the two [K+]o and the ratio of the total IP (1.39 ± 0.20, P = 0.029) at the two [K+]o were recorded and averaged.

Perhaps the best evidence that the α1-isoform is not involved in the stimulation of IP occurred serendipitously owing the adaptability of biological systems. During the summer, ventricular myocytes from guinea pigs ceased expressing the stimulation of IP. Using the hearts from these animals, we conducted parallel studies on the stimulation of IP and RNase protection assays for mRNA levels of both the α1- and α2-isoforms. A piece of the left ventricle was removed and prepared for RNase protection assays, and then the rest of the heart was used to isolate single ventricular myocytes for measurement of IP by the patch-clamp technique.

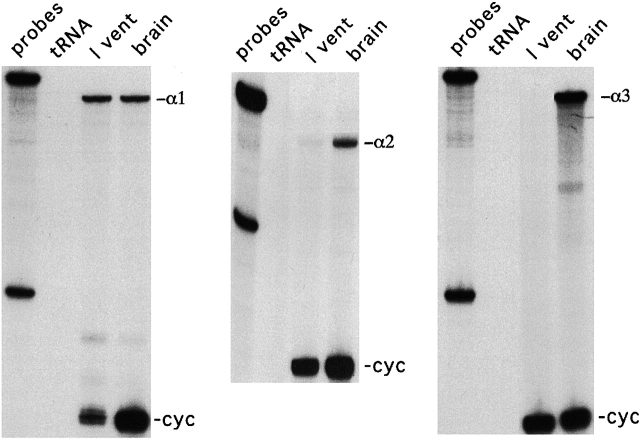

Fig. 4 shows the results from the RNase protection assays, indicating greatly reduced α2-isoform in these cells. The RNase protection assays are the same as described in our previous report (Gao et al., 1999a). mRNA for all three α-isoforms of the Na/K pump are abundantly expressed in guinea pig brain. However, the α1-isoform is the dominant transcript in guinea pig ventricle. The α2-isoform in ventricular myocytes from these hearts was present at very low levels, contributing just 6 ± 4% (SD) of the total Na/K pump mRNA based on three different samples (compared with 18% in normal samples). No α3-isoform mRNA was detected from any guinea pig heart sample. At 6% α2-isoform, our patch-clamp method is probably beyond its limit of resolution. This analysis assumes a linear relationship between [mRNA] and plasma membrane protein and equal maximum turnover rates for both pump types.

Figure 4.

RNase protection assays indicate the lack of α2-isoform in guinea pig ventricular myocytes that lacked the stimulation of IP. mRNA for the α1-, α2- and α3-isoforms of the Na/K pump are abundantly expressed in guinea pig brain. In contrast, the α1-isoform is the dominant transcript in guinea pig ventricle. The α2-isoform is present at very low levels, just 6 ± 4% (SD) of the total Na/K pump mRNA based on quantification from three different samples (compared with 18% in normal samples). No α3-isoform mRNA was detected from any guinea pig heart sample.

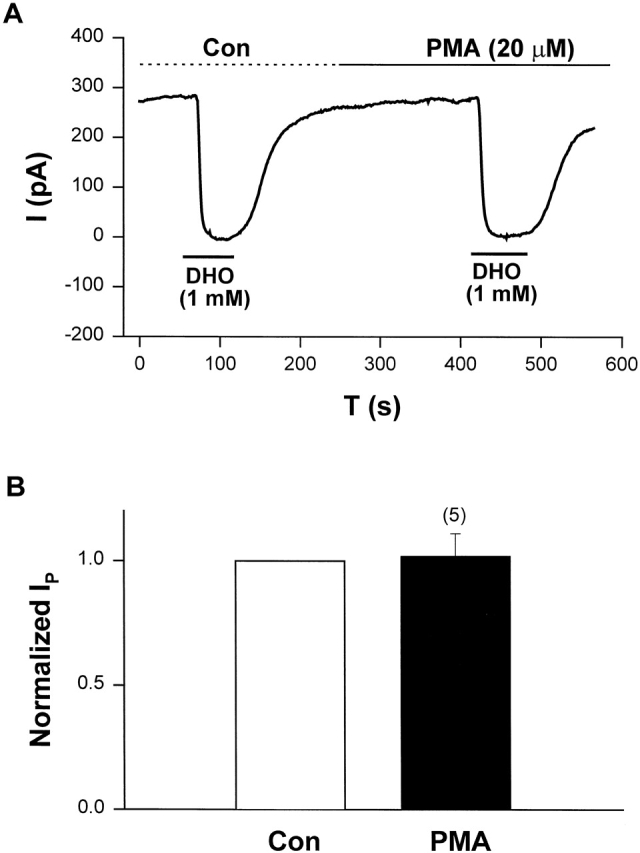

We previously reported that α-adrenergic stimulation of IP is only coupled to the α2-isoform of the Na/K pump through a PKC-mediated pathway (Wang et al., 1998; Gao et al., 1999a,b). If the α2-isoform is not present in these guinea pig ventricular myocytes, activation of PKC should not have any effect on IP. We also reported PMA has a larger effect than norepinephrine on IP2 (Wang et al., 1998; Gao et al., 1999c). Therefore, we used PMA as the activator of PKC to examine its effect on IP. Fig. 5 A shows a typical record of the effect of PMA on IP in cells lacking the α2-isoform of the Na/K pump. In these experiments, IP was measured by application of 1 mM DHO, which is essentially saturating (Gao et al., 1995). In this sample, IP in control (IP(Con)) is 284 pA, and IP in the presence of PMA (IP(PMA)) is 276 pA. Fig. 5 B shows the averaged results from a total of five cells. IP(Con) was defined as 1. In each cell the ratio IP(PMA)/IP(Con) was calculated and averaged to obtain the value 1.02 ± 0.09 (SD), indicating PMA had no effect on IP in these heart cells. These results are consistent with our previous conclusion that PKC is coupled specifically to the α2-isoform of the Na/K pumps in guinea pig myocytes, and they reinforce the conclusions based on Fig. 2 (C and D).

Figure 5.

PMA, an activator of the α2-isoform, had no effect on IP in guinea pig cardiac myocytes lacking mRNA for the α2-isoform. (A) An original holding current record showing the experimental protocol. IP was indicated by the holding current shift induced by 1 mM DHO. In this sample, IP(Con) is 284 pA, and IP(PMA) is 276 pA. (B) The averaged results from five cells. The pump currents measured in different conditions were normalized to IP(Con). Thus, IP(Con) = 1, and the normalized IP(PMA) is 1.02 ± 0.09 (P = 0.46).

A Two-site DHO-binding Model for Stimulation and Inhibition of IP

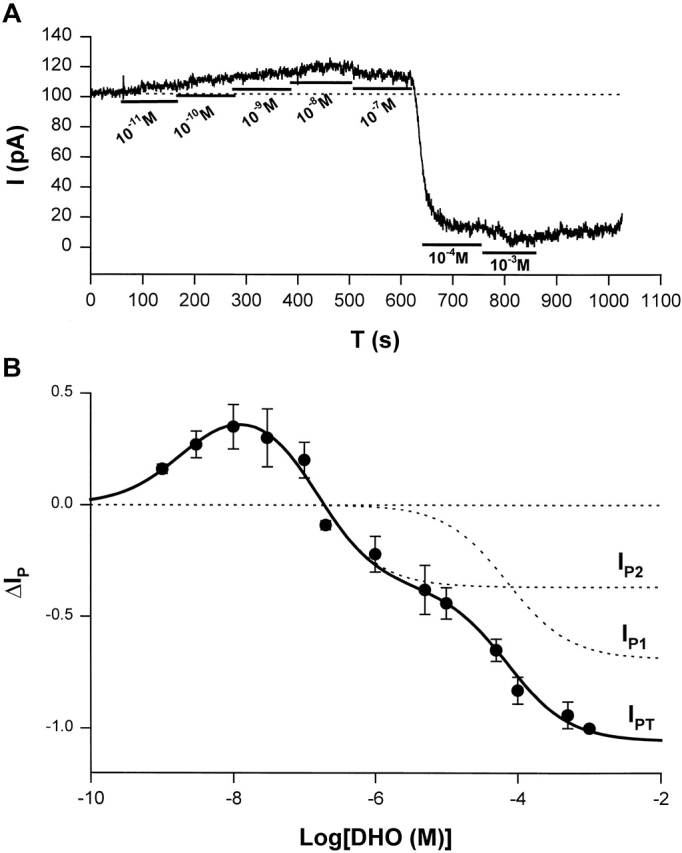

To characterize the stimulation of IP, we measured the DHO-sensitive currents as [DHO] ranged from 10−9 to 10−3 M. Then, a DHO dose–response curve was constructed. Fig. 6 A shows the protocol for measuring stimulation of IP by low [DHO] and the inhibition of IP by high [DHO]. In this cell, seven different concentrations of DHO from 10−11 to 10−3 M were applied, and then DHO was washed out. The DHO-sensitive currents (ΔIP, stimulation, or inhibition), were normalized to the maximal value of ΔIP obtained in the same cell by total pump inhibition on application of 1 mM DHO. The basal ΔIP before any application of DHO was defined as zero (Fig. 6 A, see dotted line at a holding current of 100 pA). When the DHO-induced current shifted above the basal level, due to stimulation of IP by low [DHO], we assigned ΔIP a positive value. If the induced current shifted below the basal level, due to the inhibition of IP by high [DHO], we assigned ΔIP a negative value. Since 1 mM DHO is a saturating concentration that completely blocks IP (Gao et al., 1995), we defined the ΔIP induced by 1 mM DHO as −1. In this cell, the maximum stimulation was ∼20% of total IP, whereas the average maximum stimulation shown in Fig. 6 B was 35 ± 10%.

Figure 6.

ΔIP-[DHO] relation in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. (A) An original record of holding current showing the protocol for observing stimulation of IP by low [DHO] and inhibition of IP by high [DHO]. In this cell, seven different concentrations of DHO from 10−11 to 10−3 were applied. The DHO-sensitive currents indicated the change in IP (ΔIP). (B) The ΔIP-[DHO] curve. The normalized ΔIP at each point was averaged from at least five cells, and the bars indicate SD (see results for normalization method). The points above the zero level (the dotted straight line) represent stimulation of IP, and the points below the zero level indicate IP inhibition. The maximal stimulation of IP was produced by 10 nM DHO. The smooth curves were obtained by curve fitting the points in the figure with Eq. 1. The solid smooth curve labeled by IPT was the total ΔIP, which is the sum of ΔIP contributed by the α2-isoform (IP2) and ΔIP contributed by α1-isoform (IP1). The positive values of ΔIP at DHO concentrations of 10−9, 3 × 10−9, 10−8, 3 × 10−8, and 10−7 M represent statistically significant increases in the holding current with P values of 6 × 10−9, 5 × 10−5, 10−7, 5 × 10−6, and 2 × 10−3, respectively.

Fig. 6 B shows the ΔIP-[DHO] curve. The normalized ΔIP at each point is averaged from at least five cells, and error bars indicate SD. The points above the zero level indicate stimulation of IP, and the points below the zero level indicate inhibition of IP. The maximal stimulation occurred at ∼10 nM DHO, and its percentage increase in total Na/K pump current (IPT) is 35 ± 10% (SD, n = 8).

A two-site binding model was developed to interpret our data (see ). In guinea pig ventricular myocytes, IPT is the sum of the high DHO affinity IP contributed by the α2-isoform (IP2) and the low DHO affinity IP contributed by the α1-isoform (IP1). Since only the α2-isoform seems to be involved in the stimulation of IP by low concentrations of DHO, the parallel model was described by the following equation (see for derivation),

|

(1) |

In this equation, k is the increase in IP2 when DHO is bound to the stimulatory site;  and

and  are the dissociation constants of the stimulatory and inhibitory DHO-binding sites on the α2-isoform, respectively; and K1 is the dissociation constant for the inhibitory DHO-binding site on the α1-isoform. The symbols f2 and f1 represent the fractions of IPT due to IP2 and IP1.

are the dissociation constants of the stimulatory and inhibitory DHO-binding sites on the α2-isoform, respectively; and K1 is the dissociation constant for the inhibitory DHO-binding site on the α1-isoform. The symbols f2 and f1 represent the fractions of IPT due to IP2 and IP1.

Eq. 1 was used to fit our ΔIP-DHO data in Fig. 6 B. The values of  and

and  obtained by the curve fitting are 2.1 nM and 0.15 μM, respectively, and k = 1.32. Since IP1 is not involved in the stimulation of IP, the value of K1 is fixed at 72 μM, which was the number we previously reported (Gao et al., 1995). The values of f2 and f1 determined by the fitting are 0.35 and 0.65, respectively, which are the same as those reported in Gao et al. (1995). At 10 nM [DHO], the best-fit maximum stimulation of IP2 was 107%.

obtained by the curve fitting are 2.1 nM and 0.15 μM, respectively, and k = 1.32. Since IP1 is not involved in the stimulation of IP, the value of K1 is fixed at 72 μM, which was the number we previously reported (Gao et al., 1995). The values of f2 and f1 determined by the fitting are 0.35 and 0.65, respectively, which are the same as those reported in Gao et al. (1995). At 10 nM [DHO], the best-fit maximum stimulation of IP2 was 107%.

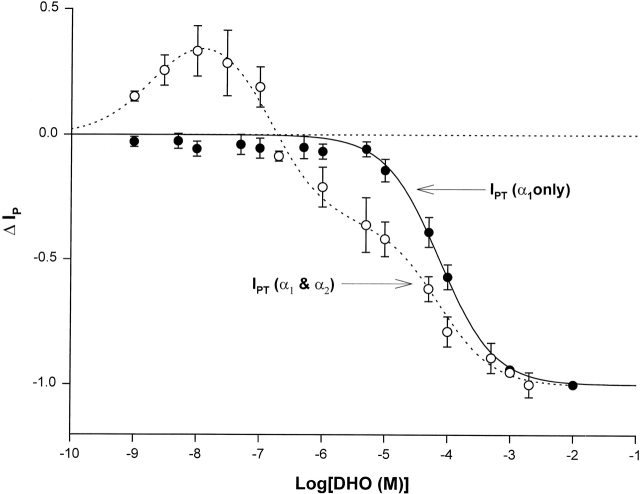

Fig. 7 compares the ΔIP–DHO curve in Fig. 6 with that recorded in cells isolated from the guinea pig hearts without the α2-isoform. Data were collected as described in Fig. 6 A. Each point was averaged from at least five cells. No stimulation of IP was observed even at 10 nM DHO in the guinea pig hearts lacking the α2-isoform. The curve fitting indicates only IP1 (α1-isoform) was present in these cells. The value of K1 given by the fitting was 74 μM, which is almost identical to the value (72 μM) we reported previously (Gao et al., 1995). These results suggest that when the α2-isoform is absent, there is no stimulation of IP, and strengthen the suggestion that the stimulation of IP involves only the α2-isoform, and not the α1-isoform.

Figure 7.

ΔIP-DHO curve in guinea pig ventricular myocytes lacking the α2-isoform. The open circles and the dashed smooth curve are the same ones presented in Fig. 3 B, indicating the ΔIP-DHO curve with two isoforms (α1 and α2). The closed circles and the solid smooth curve define the ΔIP-DHO curve lacking the α2-isoform. Stimulation of IP was not observed in the guinea pig hearts lacking the α2-isoform. The curve fitting indicates only the α1-isoform was present in these cells.

Ouabain Stimulates the Na/K Pump at Lower Concentrations than DHO

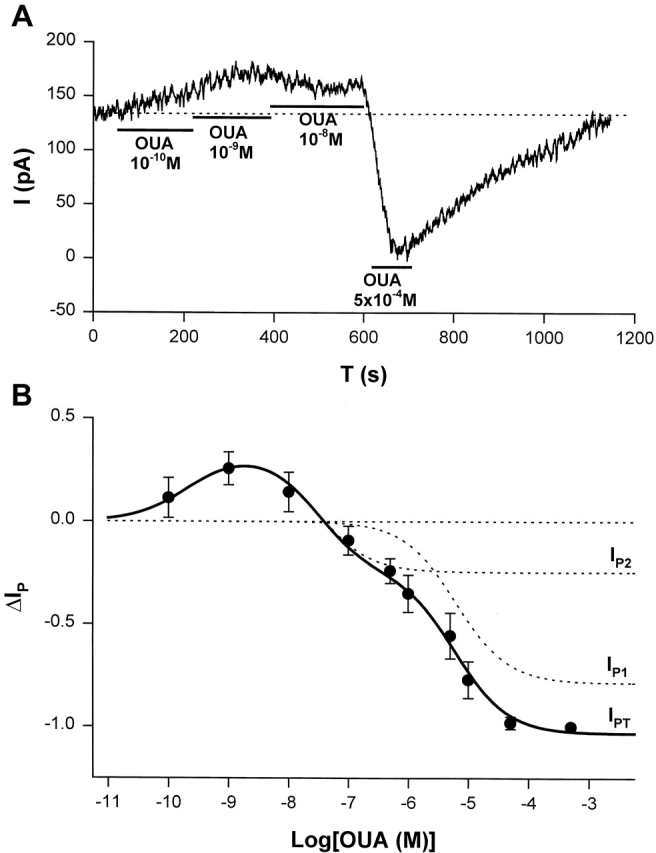

Our studies with DHO, chosen for its rapid binding and unbinding, showed that low concentrations (10−9 to 10−7 M) resulted in an increase in outward current. However, they did not demonstrate whether this “pump stimulation” was a specific action of DHO or a more general property of a class of compounds. We therefore performed similar studies with ouabain (OUA). The results of these studies are provided in Fig. 8 (A and B). A sample of the protocol is provided in Fig. 8 A. An increase in outward current is observed in response to application of 10−10 M OUA. The maximum outward current is observed at 1 nM (a concentration about an order of magnitude lower than the [DHO] required for its maximal stimulatory effect). A smaller outward current shift is observed at 10−8 M OUA. On application of 5 × 10−4 M, there is a large inward shift in holding current corresponding to total inhibition of the Na/K pump. When OUA is washed out, there is a slow return to the original holding current.

Figure 8.

ΔIp-[OUA] relation in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. (A) A sample of raw data showing the protocol for observing stimulation of Ip by low [OUA] and inhibition of Ip by high [OUA]. In this cell, four different concentrations of OUA were applied. The three low concentrations of OUA stimulated Ip and 0.5 mM OUA completely inhibited Ip (see B). Dotted line indicates the level of Ip in the absence of OUA. (B) Normalized ΔIp-[OUA] curve. In the absence of OUA, ΔIp was 0 (straight dotted line). The normalized ΔIp at each point was averaged from at least five cells, and the bars indicate SD. The points above the zero level indicate the stimulation of Ip and those points below the zero level represent the inhibition of IP. Ip was maximally stimulated by 1 nM OUA and completely inhibited by 0.5 mM OUA. The smooth curves were obtained by curve fitting the points in the figure with Eq. 1. IP1 + IP2 = IPT. The best-fit parameters were k = 1.36,  = 2.12 × 10−10 M,

= 2.12 × 10−10 M,  = 3 × 10−8 M, K1 = 6.18 × 10−6 M, f2 = 0.24, f1 = 0.76. The positive values of ΔIP at ouabain concentrations of 10−10, 10−9, and 10−8 M represent statistically significant increases in the holding current with P values of 10−3, 2 × 10−4, and 10−2, respectively.

= 3 × 10−8 M, K1 = 6.18 × 10−6 M, f2 = 0.24, f1 = 0.76. The positive values of ΔIP at ouabain concentrations of 10−10, 10−9, and 10−8 M represent statistically significant increases in the holding current with P values of 10−3, 2 × 10−4, and 10−2, respectively.

The results of all our experiments with OUA are summarized in Fig. 8 B. The figure demonstrates that application of OUA at low concentrations (10−10 to 10−8 M) results in an increase in outward current (pump stimulation), whereas higher concentrations result in an inward current shift (pump inhibition). Maximum inhibition is achieved at 10−4 M. The smooth curve is the fit of the two-site model presented in the to all our OUA data. The K d's for both the inhibitory and stimulatory sites of the high affinity pumps (IP2), and for the low affinity pump (IP1) are about an order of magnitude higher affinity than for DHO (parameters provided in Fig. 8 legend).

The α3-Isoform of the Na/K Pump Also May Be Stimulated by Nanomolar [DHO]

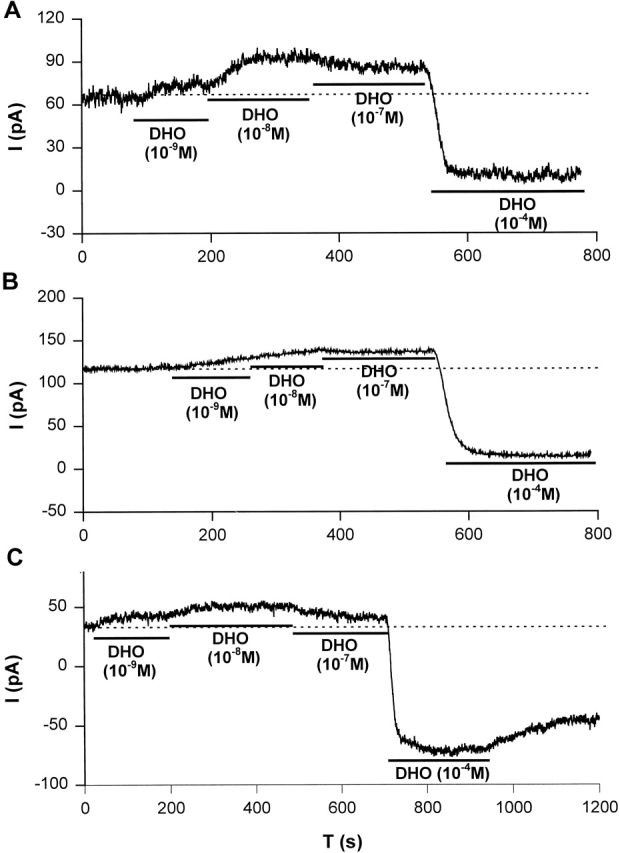

It has been reported that canine cardiac myocytes contain two distinct molecular forms (α and α+) of the Na/K ATPase catalytic subunit (Maixent et al., 1987). Of these two isoforms, [3H]ouabain-binding measurements and Na/K ATPase assays indicated α+ has a 150-fold higher affinity for ouabain than α. Maixent and Berrebi-Bertrand (1993) and Zahler et al. (1996) reported that dog left ventricle expresses α1- and α3-isoforms, but no detectable α2-isoform of the Na/K pumps. RNase protection assays (unpublished data) also indicated that the α1- and α3-isoforms but not the α2-isoform of the Na/K pump are present in canine ventricle. To examine if nanomolar [DHO] can stimulate the α3-isoform, we investigated the effects of low concentrations of DHO on IP in canine cardiac myocytes. Fig. 9 shows stimulation of IP by low concentrations of DHO and inhibition of IP by a high [DHO] in canine atrial (Fig. 9 A), ventricular epicardial (Fig. 9 B), and ventricular endocardial (Fig. 9 C) cells. Similar observations were obtained from at least five cells from each region. These results suggest that the α3-isoform is also stimulated by nanomolar [DHO].

Figure 9.

Stimulation of IP in canine cardiac myocytes. Stimulation of IP by low concentrations of DHO (10−9, 10−8, and 10−7 M) and the inhibition of IP by a high concentration of DHO (10−4 M) were observed in canine atrial (A), ventricular epicardial (B), and ventricular endocardial (C) cells. The dotted lines indicate the holding current in the absence of DHO. Similar results were obtained from at least five cells from each region.

Stimulation of IP in Human Heart Cells

Three α-isoforms (α1, α2, and α3) of the Na/K pump are reported to be present in human heart (Shamraj et al., 1991; Zahler et al., 1993). Thus, stimulation of IP by low concentrations of cardiac glycosides also may occur in human heart cells, but there have been no studies on this effect. Therefore, we examined the effect of low [DHO] on IP in human heart cells.

Fig. 10 (A and B) shows original current recordings indicating stimulation of IP by low [DHO] and the inhibition of IP by high [DHO] are indeed present in human ventricular and atrial myocytes, respectively. Similar results were observed in eight cells in each cell type. The effects of α- and β-adrenergic activation on IP in the human atrial cells were investigated using the same protocols described for Fig. 2. In Fig. 10 C, IP was normalized to the membrane capacitance. IP averaged from 12 cells in the control is 0.29 ± 0.06 pA/pF (SD), and IP averaged from 8 cells in the group of ISO treatment (β-adrenergic activation) was 0.29 ± 0.04 pA/pF, suggesting no difference between control and ISO-treated cells. However, IP from 13 cells in the group of NE-treatment (α-adrenergic activation) was 0.36 ± 0.06 pA/pF, indicating a significant increase over control (P < 0.01). These results suggest that the Na/K pump current in human atrial cells has similar properties to the α2-isoform in guinea pig ventricle.

Fig. 10 D shows the ΔIP-DHO curve from human atrial cells. Data were collected and normalized as described in Fig. 6 A. Each point was averaged from at least five cells. The points above the zero level indicate stimulation of IP, and those below the zero level indicate inhibition of IP. The fully blocking concentration of DHO for the human atrial cells was 10−4 M. As in guinea pig ventricular myocytes, the maximal stimulation of IP occurred at ∼10 nM DHO, and the percent increase in IPT is 29 ± 6% (SD, n = 8). The equation to fit these data is the same as that used in guinea pig ventricular myocytes, but the term for IP1 was omitted, since all isoforms of the Na/K pumps in human heart have a relatively high affinity for DHO. This does not imply the α1-isoform of the Na/K pump is not present. It simply means the α1-isoform cannot be distinguished using DHO-binding assays. K+ and K− are the dissociation constants of the stimulatory and inhibitory binding sites, respectively. The values of K+ and K− given by the curve fitting are 0.84 nM and 1.7 μM, which are similar to those observed for the α2-isoform of guinea pig ventricular myocytes.

DISCUSSION

We have presented evidence for stimulation of IP by low concentrations of glycosides in human (atrial and ventricular), canine (endocardial and epicardial), and guinea pig ventricular myocytes. An increase in outward current was observed at concentrations of DHO ranging from 1 to 100 nM. The increase did not occur when IP was blocked by removal of either external K+ or intracellular Na+, or addition of intracellular vanadate, suggesting the Na/K pumps generated the current. The maximum stimulation occurred at 10 nM DHO and ranged between 29 and 35% of total pump current, depending on the preparation examined. The actual stimulation of current generated by the high DHO affinity isoforms was probably much greater, but it could only be estimated in the guinea pig ventricular myocytes, where we have data on the fraction of IPT due to IP2. In these cells, IP2 was maximally increased by 107%.

Previous studies by others in multicellular tissues have suggested that low concentrations of cardiac glycosides might stimulate the Na/K pump (for review see Noble, 1980). The strongest evidence suggesting stimulation of IP was the measurement of changes in [Na+]i and [K+]i. Hagen (1939) and Boyer and Poindexter (1940) first reported low concentrations of glycosides increase [K+]i in cardiac tissues. Godfraind and Ghyset-Burton (1977)(1979) studied this effect in some detail. They found that 10−9 and 5 × 10−9 M ouabain caused a significant increase in [K+]i and a corresponding significant decrease in [Na+]i in guinea pig atria. Cohen et al. (1976) studied the influence of low concentrations of ouabain on the reversal potential of a K+-current in sheep Purkinje fibers. They observed a shift of the reversal potential in the negative direction, indicating a decrease in extracellular (cleft) [K+]o and suggesting stimulation of the Na/K pump. In addition, Gadsby and Cranefield (1982) suggested there was stimulation of IP in canine Purkinje fibers. However, as they pointed out, [K+]o and [Na+]i cannot be well controlled in multicellular tissues. Changes in [K+]o or [Na+]i or both could have dramatically affected activity of the Na/K pump, hence, stimulation of IP was uncertain.

We used single heart cells and the whole-cell patch-clamp technique to investigate the effect of low concentrations of glycoside on IP. The pipette solution contained 80 mM Na+ to saturate the Na+-binding sites of the Na/K pump, so changes in [Na+]i on the order of 10 mM would have little effect on Na/K pump current. To minimize K+ concentration changes in the T-system lumen, K+ conductance was blocked with 20 mM TEA+ and 30 mM Cs+ in the pipette solution, and 2 mM Ba2+ in the bath. We also added 1 mM Cd2+ in the external Tyrode solution to block the L-type Ca2+ channels and the Na/Ca exchanger. The heart cells were held at 0 mV, where the IP-voltage curve reaches its maximum, and where the cell membrane resistance is higher than at diastolic potentials, so the ratio of signal to noise was increased. In our experimental conditions, the increase in outward current induced by low concentrations of DHO was observed, and did not occur when IP was inhibited with removal of either extracellular K+ or intracellular Na+, or when vanadate was included in the pipette solution, suggesting low concentrations of glycoside indeed stimulate IP.

Studies using molecular biological techniques have demonstrated the Na/K pump is a multigene family of proteins (for reviews see Sweadner, 1989; Geering, 1990). To date, four α-isoforms of the Na/K pump have been found. Of the α-isoforms, α2 and α3 have a higher affinity for ouabain than α1. More recently, we reported that α1- and α2-isoforms coexist in guinea pig ventricle (Gao et al., 1999a), where they probably function as the low DHO affinity and the high DHO affinity pumps (Mogul et al., 1989; Gao et al., 1995). We also reported isoform-specific regulation of the Na/K pump by α- and β-adrenergic agonists. The α1-isoform could be stimulated or inhibited by the β-agonist ISO, depending on [Ca2+]i, but it is insensitive to α-adrenergic activation, whereas the α2-isoform is stimulated by α-adrenergic activation but it is insensitive to β-adrenergic agonists (Gao et al., 1999a). This isoform-specific regulation provided a strategy to identify which α-isoform(s) of the Na/K pump is stimulated by low concentrations of glycoside. In guinea pig ventricular myocytes, stimulation of IP is increased by α-adrenergic activation but insensitive to β-adrenergic activation, the same as IP2. In some guinea pig hearts, expression of the α2-isoform was dramatically decreased, and so was the stimulation of IP. These data suggest that only the α2-isoform is involved in the stimulation of IP in guinea pig heart. Moreover, the occasional loss of expression of the α2-isoform may explain why stimulation of IP was not observed in some studies (Kasturi et al., 1997). We observed stimulation of Ip with OUA as well as DHO, suggesting that DHO is not unique in this action. The dissociation constants for stimulation and inhibition for OUA were about an order of magnitude higher affinity than those for DHO. We also observed stimulation of IP in canine ventricular myocytes. Previous reports (Maixent et al., 1987; Maixent and Berrebi-Bertrand, 1993; Zahler et al., 1996) and our present study have found the α1- and the α3-isoforms of the Na/K pump coexist in canine heart cells. If the α1-isoform is insensitive to nanomolar DHO, as in guinea pig ventricle, the α3-isoform must be the source of the stimulation of IP in canine ventricle.

Our results from human heart cells have some ambiguities that make it uncertain which α-isoform(s) are stimulated by nanomolar DHO. We do not know which isoforms were present in these cells or the regulatory paths for the different isoforms. Moreover, the dissociation constants for inhibition by DHO are similar for the three isoforms (Shamraj et al., 1993), so we could not functionally separate the responses of the high versus low DHO affinity pumps. Zahler et al., 1993, reported the α-isoform mRNA in normal human left ventricle is 62.5% α1, 15% α2, and 22.5% α3. However, Allen et al. (1992) and Shamraj et al. (1993) reported proportions of the α2- and α3-isoforms that were double those reported by Zahler. The cells we used were from the atrial tab of diseased hearts, and Zahler et al. (1993) also reported there was an increase in α3-isoform in the failing heart. However, other studies in diseased hearts reported a decrease in [3H]ouabain binding (Shamraj et al., 1993; Ellingsen et al., 1994; Bundgaard and Kjeldsen, 1996; Larsen et al., 1997), suggesting a reduction in the expression of total Na/K pumps. Given these diverse results, it is not possible to make a reasonable guess on the isoform composition of the cells we used. And given the similar dissociation constants for inhibition by DHO, we could not even estimate the fraction of α1-isoform. The stimulation of IP observed in these heart cells might be due to the α2- and the α3-isoforms. The maximal stimulation of total IPT recorded in Fig. 10 D was ∼30%, which is a much smaller effect than the 107% increase in IP2 in guinea pig and, therefore, consistent with the presence of a significant amount of α1-isoform that is insensitive to nanomolar DHO. The results in Fig. 10 C indicated a 24% increase of total IPT by α-adrenergic activation, which is a much smaller effect than the 38% increase in IP2 observed in guinea pig ventricular myocytes (Gao et al., 1999a), which again is consistent with the presence of significant α1-isoform that is insensitive to α-adrenergic activation. However, the results in Fig. 10 C also indicate that β-adrenergic activation had no effect on total IPT, which is not consistent with the presence of α1-isoform, unless regulation in human atrium differs from that in guinea pig ventricle. More detailed information will only be available with heterologous expression as in the studies of Crambert et al. (2000).

The mechanism of the stimulation of IP by low concentrations of glycosides is not well understood. Hougen et al. (1981) observed an increase in Rb+ uptake induced by nanomolar ouabain in guinea pig left atria. This stimulation of the Na/K pump was prevented by the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol, by depletion of endogenous norepinephrine with either reserpine or 6-hydroxydopamine, or by pretreatment with β-adrenergic agonists. Other results indicated OUA promoted the release of endogenous norepinephrine from sympathetic nerve endings in intact tissue as well as inhibiting norepinephrine uptake (Seifen, 1974; Harvey, 1975). Therefore, Hougen et al. (1981) concluded that the stimulatory effect of low concentrations of OUA on the Na/K pump is mediated, at least in part, by β-adrenergic effects of endogenous catecholamines released from nerve terminals. However, we used isolated single heart cells, instead of heart tissue, and nerve terminals were absent. When the β-blocker propranolol was added to the bath, the stimulation was still present in our isolated cells. Therefore, the endogenous catecholamine release mechanism cannot explain stimulation of IP in the present study. Furthermore, in our experimental conditions, high [Na+]i saturated the Na+-binding sites of the Na/K pump. Moreover, K+ conductance was significantly reduced by Cs+, TEA+, and Ba2+. In these conditions, stimulation of IP is unlikely to be explained by a secondary effect of DHO. Our results suggest that the stimulation of IP is a direct action of low concentrations of glycosides on the cardiac Na/K pump, and is only associated with the α2- and the α3-isoforms.

In conclusion, we observed stimulation of IP in myocytes from guinea pig, canine, and human hearts. This stimulation appears to be a direct action of low concentrations of glycosides, and it is most likely coupled to only the α2- and α3-isoforms of the Na/K pump. Further studies are necessary to understand the molecular basis of the stimulation and its functional significance. It could represent another mechanism of isoform-specific regulation, in this instance by endogenous glycoside-like compounds (Kolbel and Schreiber, 1996; Jortani and Valdes, 1997). Finally, we do not know the relationship, if any, of this stimulation to the inotropic effect of cardiac glycosides.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the American Heart Association and by grants HL28958, HL54031, HL67101, and HL20558 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

APPENDIX

A Two Binding–site Model for DHO Stimulation and Inhibition of the Cardiac Na/K Pump

We do not have enough data to generate a unique model for our observations, however, it is useful to have a quantitative framework to store and easily recreate our observations. The simplest model that fits our data and is consistent with other observations assumes two binding sites for DHO: (1) a high affinity stimulatory site (R+) and (2) a low affinity inhibitory site (R−). Because the binding data suggest only 1 DHO per pump protein, we assume R+ and R− are competitive for DHO. Moreover, ATPase assays indicate total blockade by high concentrations of DHO, so we also assume that when R+ is filled, R− is available, but once R− is filled, R+ releases the bound DHO, if present, and becomes unavailable for binding.

SCHEME I.

|

where D is the DHO concentration, and P− is the inhibited pump. Thus,

|

When R+ is occupied by DHO, the pump is stimulated, i.e.,

SCHEME II.

P+ is the stimulated pump. The R+ site is not available in those pumps with the R− site filled, hence,

|

|

Then,

|

where IP is pump current, Imax is the pump current at zero [DHO], k is the increase in current by each pump when R+ is bound to DHO, and P is the fraction of unbound pumps, P = 1 − P+ − P−. The normalized change in pump current is therefore:

|

The above equation was used in Fig. 6 to fit the DHO effects on the α2-isoform.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: DHO, dihydro-ouabain; ISO, isoproterenol; NE, norepinephrine; OUA, ouabain; PROP, propranolol.

References

- Akera, T., K. Takeda, S. Yamamoto, and T.M. Brody. 1979. Effects of vanadate on Na+,K+-ATPase and on the force of contraction in guinea-pig hearts. Life Sci. 25:1803–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.D., T.A. Schmidt, J.D. Marsh, and K. Kjeldsen. 1992. Na,K-ATPase expression in normal and failing human left ventricle. Basic Res. Cardiol. 87(Suppl.):87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahinski, A., A.C. Nairm, P. Greengard, and D.C. Gadsby. 1989. Chloride conductance regulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cardiac myocytes. Nature. 340:718–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi-Bertrand, I.J., M. Maixent, F.G. Guede, A. Gerbi, D. Charlemagne, and L.G. Lelievre. 1991. Two functional Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms in the left ventricle of guinea pig heart. Eur. J. Biochem. 196:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, P.K., and C.A. Poindexter. 1940. The influence of digitalis on the electrolyte and water balance of heart muscle. Am. Heart J. 20:556–591. [Google Scholar]

- Bundgaard, H., and K. Kjeldsen. 1996. Human myocardial Na,K-ATPase concentration in heart failure. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 163-164:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, I., J. Daut, and D. Noble. 1976. An analysis of the actions of low concentrations of ouabain on membrane currents in Purkinje fibers. J. Physiol. 260:75–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, I.S., N.B. Datyner, G.A. Gintant, N.K. Mulrine, and P. Pennefather. 1987. Properties of an electrogenic sodium-potassium pump in isolated canine Purkinje myocytes. J. Physiol. 383:251–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crambert, G., U. Hasler, A.T. Beggah, C. Yu, N.N. Modyanov, J.-D. Horisberger, L. Lelievre, and K. Geering. 2000. Transport and pharmacological properties of nine different human Na,K-ATPase isozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1976–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsen, O., M. Ree Holthe, A. Svindland, G. Aksnes, O.M. Sejersted, and A. Ilebekk. 1994. Na,K-pump concentration in hypertrophied human hearts. Eur. Heart J. 15:1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, A.A.L., U. Borchard, and M. Neumann. 1983. Effects of vanadate on isolated vascular tissue: biochemical and functional investigations. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 5:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby, D.C., and P.F. Cranefield. 1982. Effects of electrogenic sodium extrusion on the membrane potential of cardiac Purkinje fibers. Normal and Abnormal Conduction in the Heart. A.P. de Carvalho, B.F. Hoffman, and M. Lieberman, editors. Futura, Mount Kisco, New York. 225–247.

- Gao, J., R.T. Mathias, I.S. Cohen, and G.J. Baldo. 1992. Isoprenaline, Ca2+ and the Na/K pump in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 449:689–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., R.T. Mathias, I.S. Cohen, and G.J. Baldo. 1995. Two functionally distinct Na/K pumps in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 106:995–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., R. Wymore, R.T. Wymore, Y. Wang, D. McKinnon, J.E. Dixon, R.T. Mathias, I.S. Cohen, and G.J. Baldo. 1999. a. Isoform-specific regulation of the sodium pump by α- and β-adrenergic agonists in guinea pig ventricular ventricle. J. Physiol. 516:377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., Y. Wang, R.T. Mathias, and I.S. Cohen. 1999. b. The effect of PKC on the Na/K pump is only coupled to the α2-isoform in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 76:A85. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., R.T. Mathias, I.S. Cohen, Y. Wang, X. Sun, and G.J. Baldo. 1999. c. Activation of PKC increases Na/K pump current in ventricular myocytes from guinea pig heart. Pflügers Arch. 437:643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geering, K. 1990. Subunit assembly and functional maturation of Na/K ATPase. J. Membr. Biol. 115:109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind, T., and J. Ghyset-Burton. 1977. Binding sites related to ouabain-induced stimulation or inhibition of the sodium pump. Nature. 265:165–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfraind, T., and J. Ghyset-Burton. 1979. Stimulation and inhibition of the sodium pump by cardiotonic steroids in relation to their binding sites and their inotropic effect on guinea-pig isolated atria. Br. J. Pharmacol. 66:175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, P.S. 1939. The effect of digilanid C in varying dosages upon the potassium and water content of rabbit heart muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 67:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, R.D., and J.R. Hume. 1989. Autonomic regulation of a chloride current in heart. Science. 244:983–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S.C. 1975. The effects of ouabain and phenytoin on myocardial norepinephrine. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 213:222–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougen, T.J., N. Spicer, and T.W. Smith. 1981. Stimulation of monovalent cation active transport by low concentrations of cardiac glycosides. Role of catecholamines. J. Clin. Invest. 68:1207–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, G., and U. Klockner. 1982. Calcium tolerant ventricular myocytes prepared by preincubation in a “KB” medium. Pflügers Arch. 395:6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jortani, S.A., and R. Valdes, Jr. 1997. Digoxin and its related endogenous factors. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 34:225–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasturi, R., L.R. McLean, M.N. Margolies, and W.J. Ball, Jr. 1997. High affinity anti-digoxin antibodies as model receptors for cardiac glycosides: comparison with Na+,K+-ATPase. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 834:634–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbel, F., and V. Schreiber. 1996. The endogenous digitalis-like factor. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 160:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J.S., T.A. Schmidt, H. Bundgaard, and K. Kjeldsen. 1997. Reduced concentration of myocardial Na+,K+-ATPase in human aortic valve disease as well as of Na+,K+- and Ca2+-ATPase in rodents with hypertrophy. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 169:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maixent, J.M., and I. Berrebi-Bertrand. 1993. Turnover rates of the canine cardiac Na,K-ATPases. FEBS Lett. 330:297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maixent, J.M., D. Charlemagne, B. De La Chapelle, and L.G. Lelievre. 1987. Two Na,K-ATPase isoenzymes in canine cardiac myocytes: molecular basis of inotropic and toxic effects of digitalis. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6842–6848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, R.T., I.S. Cohen, J. Gao, and Y. Wang. 2000. Isoform-specific regulation of the Na+-K+ pump in heart. News Physiol. Sci. 15:176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogul, D.J., H.H. Rasmussen, D.H. Singer, and R.E. Ten Eick. 1989. Inhibition of Na-K pump current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes by dihydroouabain occurs at high- and low-affinity sites. Circ. Res. 64:1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble, D. 1980. Mechanism of action of therapeutic levels of cardiac glycosides. Cardiovasc. Res. 14:495–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, C., I.S. Cohen, and R.T. Mathias. 1988. Calculations of time constants for intracellular diffusion in whole cell patch clamp configuration. Biophys. J. 54:791–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifen, E. 1974. Evidence for participation of catecholamines in cardiac action of ouabain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 26:115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamraj, O.I., D. Melvin, and J.B. Lingrel. 1991. Expression of Na,K-ATPase isoforms in human heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 179:1434–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamraj, O.I., I.L. Grupp, G. Grupp, D. Melvin, N. Gradoux, W. Kremers, J.B. Lingrel, and A. De Pover. 1993. Characterization of Na/K-ATPase, its isoforms, and the inotropic response to ouabain in isolated failing human hearts. Cardiovasc. Res. 27:2229–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweadner, K.J. 1989. Isozymes of the Na/K ATPase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 988:185–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, K., T. Akera, S. Yamamoto, and I.S. Sheih. 1980. Possible mechanisms for inotropic actions of vanadate in isolated guinea pig and rat heart preparations. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 314:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., J. Gao, R.T. Mathias, I.S. Cohen, X. Sun, and G.J. Baldo. 1998. α-Adrenergic effects on Na+-K+ pump current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 509:117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo, A.L., P.F. James, and J.B. Lingrel. 1999. Characterization of the fourth alpha isoform of the Na,K-ATPase. J. Membr. Biol. 169:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahler, R., M. Gilmore-Hebert, W. Sun, and H. Benz, Jr. 1996. Na, K-ATPase isoform gene expression in normal and hypertrophied dog heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 91:256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahler, R., M. Gilmore-Hebert, J.C. Baldwin, K. Franco, and H. Benz, Jr. 1993. Expression of α-isoforms of the Na,K-ATPase in human heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1149:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]