Abstract

Kainate receptors (KARs) are involved in the modulation and transmission of nociceptive information from peripheral afferents to neurons in the spinal cord and trigeminal dorsal horns. KARs are found at both pre- and postsynaptic sites in the dorsal horn. We hypothesized that KARs and Substance P (SP), a modulatory neuropeptide that is used as a marker of nociceptive afferents, have a complex interactive relationship. To determine the cellular relationship and connectivity between KARs and SP afferents, we used electron microscopic dual immunocytochemical analysis to examine the ultrastructural localization of KAR subunits GluR5, 6 and 7 (GluR5,6,7) in relation to SP within laminae I and II in the rat trigeminal dorsal horn. KARs were distributed both postsynaptically in dendrites and somata (51% of GluR5,6,7 immunoreactive (-ir) profiles) and presynaptically in axons and axon terminals (45%). We also found GluR5,6,7-ir glial profiles (5%). The majority of SP-ir profiles were presynaptic axons and axon terminals. SP-ir dendritic profiles were rare, yet 23% contained GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity. GluR5,6,7 and SP were also colocalized at presynaptic sites (18% of GluR5,6,7-ir axons and axon terminals contained SP; while 11% of SP-ir axons and axon terminals contained GluR5,6,7). The most common interaction between KARs and SP we observed was GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites contacted by SP-ir axon terminals; 54% of the dendritic targets of SP-ir axon terminals were GluR5,6,7-ir. These results provide anatomical evidence that KARs primarily mediate nociceptive transmission postsynaptic to SP-containing afferents and may also modulate the presynaptic release of SP and glutamate in trigeminal dorsal horn.

Keywords: Kainate receptor, substance P, nociception, glutamate receptor, immunocytochemistry, electron microscopy

1. Introduction

The kainate receptor (KAR) is one of three subtypes of ionotropic glutamate receptor that mediate excitatory neurotransmission in the central nervous system (Hollmann and Heinemann, 1994). KARs also play a role in modulating presynaptic glutamate release (Frerking and Nicoll, 2000; Kerchner et al., 2001; Kerchner et al., 2002; Jaskolski et al., 2005; Lucifora et al., 2006). The KARs are composed of tetrameric combinations of five subunits, GluR5, GluR6, GluR7, KA1 and KA2 (Hollmann and Heinemann, 1994; Pinheiro and Mulle, 2006). The KAR subunits can form homomeric or heteromeric receptors, although to have a functional KAR, the GluR5, GluR6 or GluR7 subunit must be present (Pinheiro and Mulle, 2006). The subunit composition of the KAR modulates the pharmacological and physiological properties of the receptor, such as sensitivity to antagonists, rectification properties, desensitization and calcium permeability (Ruscheweyh and Sandkuhler, 2002; Pinheiro and Mulle, 2006).

KARs have been implicated in mediating the transmission of nociceptive information from the periphery to the central nervous system. Behavioral studies using antagonists that targeted both KARs and AMPA receptors (AMPARs) have provided support, although not definitive, for a role of KARs in acute (Nasstrom et al., 1992; Advokat and Rutherford, 1995; Szekely et al., 1997; Blackburn-Munro et al., 2004) and persistent pain states (Simmons et al., 1998; Blackburn-Munro et al., 2004; Szekely et al., 1997; Okano et al., 1998; Nishiyama et al., 1999). Electrophysiological studies have provided additional support for a role of KARs in nociceptive transmission and have also functionally localized kainate receptors to pre- and postsynaptic structures in the pain pathway of the spinal cord and spinal trigeminal nucleus (Huettner, 1990; Sahara et al., 1997; Li et al., 1999).

KARs have a complex anatomical distribution in sensory systems. KARs have been found in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) cell bodies (Petralia et al., 1994; Lucifora et al., 2006), peripheral myelinated and unmyelinated sensory axons (Coggeshall and Carlton, 1998; Hwang et al., 2001) and presynaptic terminals in spinal dorsal horn (Hwang et al., 2001; Lucifora et al., 2006). KARs also have been found postsynaptically in dendrites and cell bodies in the superficial laminae of the rat spinal dorsal horn (Hwang et al., 2001; Lucifora et al., 2006). There is evidence for a glial distribution of KAR subunits in the spinal cord (Lucifora et al., 2006). KARs also have been found in the dorsal horn of the spinal trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (Vc), an area that is functionally analogous to the spinal cord dorsal horn (Dubner and Bennett, 1983). Autoradiography of kainate binding sites shows a high density in laminae I and II and lower densities in the deeper laminae of Vc (Tallaksen-Greene et al., 1992). Immunocytochemical studies have also found moderate labeling of KAR subunits in the Vc region of brainstem (Petralia et al., 1994). Taken together, these studies support KARs as important contributors to excitatory nociceptive transmission within the dorsal horn of both the spinal cord and the Vc region of the spinal trigeminal nucleus in brainstem. Given the mixed pre- and postsynaptic distribution of KAR subunits, we sought to better define the specific roles of KARs in nociceptive transmission by determining the electron microscopic distribution of KAR subunits in relation to substance P (SP), a marker of primary nociceptive afferents. Our studies focused on the KAR distribution in the trigeminal dorsal horn, the area of input for peripheral afferents from the head.

We considered SP to be a functionally significant choice to define the connectivity of KAR-containing cellular structures to nociceptive afferents. Knockout mice for the SP precursor peptide, preprotachykinin A, have diminished responses to intensely painful stimuli in these animals (Cao et al., 1998). Studies have also demonstrated changes in SP release in the spinal cord dorsal horn following C-fiber stimulation (Yaksh et al., 1980; Go and Yaksh, 1987; Brodin et al., 1987; Yaksh et al., 1988; Duggan et al., 1988; Afrah et al., 2002) and noxious cutaneous stimulation (Go and Yaksh, 1987; Duggan et al., 1988; Kuraishi et al., 1989; McCarson and Goldstein, 1991; Allen et al., 1997), as well as in inflammatory (Yaksh et al., 1980; Kuraishi et al., 1989; Schaible et al., 1990; Sluka et al., 1992; Galeazza et al., 1995; Honore et al., 1999; Calcutt et al., 2000) and nerve injury pain states (Jessell et al., 1979; Malcangio et al., 2000). SP is released in the spinal trigeminal nuclei in brainstem following noxious chemical stimulation of dura mater encephali and the nasal mucosa (Schaible et al., 1997) as well as electrical stimulation of trigeminal ganglia (Samsam et al., 1999). Increases in SP immunoreactivity in trigeminal ganglia cells and terminals within Vc after orofacial inflammatory injury further implicate SP as a nociceptive modulator in the brainstem (Hutchins et al., 2000; Neubert et al., 2000).

SP, like KARs, has been localized to cells in dorsal root ganglia, small, unmyelinated primary afferent axons (C-fibers) and axon terminals that terminate in the spinal cord dorsal horn and caudal spinal trigeminal nuclei (Hokfelt et al., 1975; Pickel et al., 1977; Ljungdahl et al., 1978; Barber et al., 1979; Willis, 1985; Battaglia and Rustioni, 1988; De Biasi S. and Rustioni, 1988; Levine et al., 1993; Sugimoto et al., 1997). Axon terminals in the spinal cord dorsal horn containing SP have been found to preferentially target the cell bodies and dendritic processes of neurons mediating transmission of noxious peripheral stimuli, implicating a role for SP in nociception (Pickel et al., 1977; DeKoninck Y. et al., 1992). The Vc region of the spinal trigeminal nucleus also receives input from SP-containing nociceptive primary afferents from the head and face (Priestley et al., 1982).

Previous studies have suggested that SP and glutamate may be co-released during noxious stimulation and may act synergistically to enhance the pain response. Microiontophoretic application of SP enhances the responses of spinothalamic tract dorsal horn neurons to excitatory amino acid (EAA) application and noxious mechanical stimulation (Dougherty and Willis, 1991; Dougherty et al., 1993). In freshly dissociated spinal dorsal horn neurons, SP appears to potentiate NMDA and AMPA receptor-mediated, but not KAR-mediated, responses (Randic et al., 1993; Rusin et al., 1993). However, behavioral studies have demonstrated that intrathecal administration of SP with agonists for the KAR as well as for the NMDA receptor (NMDAR) and AMPAR, potentiates caudally-directed biting and scratching in mice (Mjellem-Joly et al., 1991). There is also evidence to support an interaction between KARs and SP in a recent study showing that 10% of GluR5-immunoreactive (-ir) DRG neurons were also SP-ir (Lucifora et al., 2006). We sought to determine the cellular relationship and connectivity between KARs and SP afferents by examining the ultrastructural localization of the GluR5, 6 and 7 (GluR5,6,7) KAR subunits and SP within laminae I and II of the trigeminal dorsal horn.

2. Results

2.1. The light microscopic distribution of GluR5,6,7 and SP overlapped in trigeminal dorsal horn

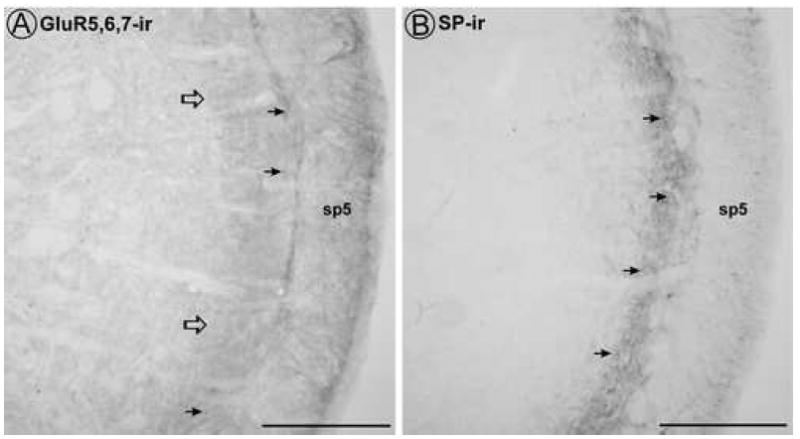

GluR5,6,7 and SP immunoreactivity were both localized to lamina I and outer lamina II of the dorsal horn of the spinal trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (Vc; Fig. 1). Diffuse GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was seen throughout the trigeminal dorsal horn, but was somewhat denser in the outer laminae. SP immunoreactivity was primarily localized to fibers and punctate varicosities in laminae I and II. The localization of both GluR5,6,7 and SP immunoreactivity to the superficial trigeminal dorsal horn supports a possible interactive relationship between KARs and SP. However, analysis at the ultrastructural level is required to determine the exact nature of this relationship.

Figure 1.

By light microscopy, diffuse GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity and punctate SP immunoreactivity are found in the superficial trigeminal dorsal horn. A. Some punctate GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity (filled arrows) are present among the diffuse GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity in laminae I and II (open arrows). B. Punctate SP immunoreactivity (filled arrows) is present throughout the superficial trigeminal dorsal horn. sp5 = trigeminal tract. Scale bar = 200 μm.

2.2. Ultrastructural analysis revealed the specific subcellular localization of GluR5,6,7 and SP in trigeminal dorsal horn

GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was found postsynaptically in both small and large dendrites (Table 1; Figs. 2, 3). GluR5,6,7 immunoreactive (-ir) dendrites that received contacts from axon terminals had an average diameter of 0.99 ± 0.03 μm (n = 396; range of diameters: 0.25 – 3.5 μm). GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites primarily received asymmetric synaptic contacts from unlabeled axon terminals (Fig. 2A), consistent with excitatory synaptic input. In a subset of animals in which GluR5,6,7 was labeled with immunogold, we determined whether the gold particles were localized to the cytoplasm or at the plasma membrane. Membrane labeling would indicate that KARs were accessible to exogenous ligand and capable of contributing to neuronal excitation (Jaskolski et al., 2005). In those dendritic profiles that contained GluR5,6,7 immunogold labeling (n = 643), only 21% had at least one gold particle localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A; 3B-C), suggesting that KAR subunits GluR5,6,7 were primarily at cytoplasmic sites (Fig. 2A,D; 3A-C). GluR5,6,7-ir somata were observed (Table 1), although less frequently than dendrites. This was primarily due to the relative frequency of encountering cell bodies versus dendrites by electron microscopy.

Table 1.

Classification of neuronal profiles containing GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity or SP immunoreactivity in trigeminal dorsal horn*

| Antigen | N | Soma | Dendrites | Axons | Terminals | Glia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GluR5,6,7 | 1402 | 28 (2%) | 681 (49%) | 386 (27%) | 236 (17%) | 71 (5%) |

| SP | 1015 | 3 (0.3%) | 34 (3%) | 466 (46%) | 512 (50%) | 0 |

Each column in the table indicates numbers of profiles in that category for each antigen. Percentages indicate the breakdown across the table within that antigen group.

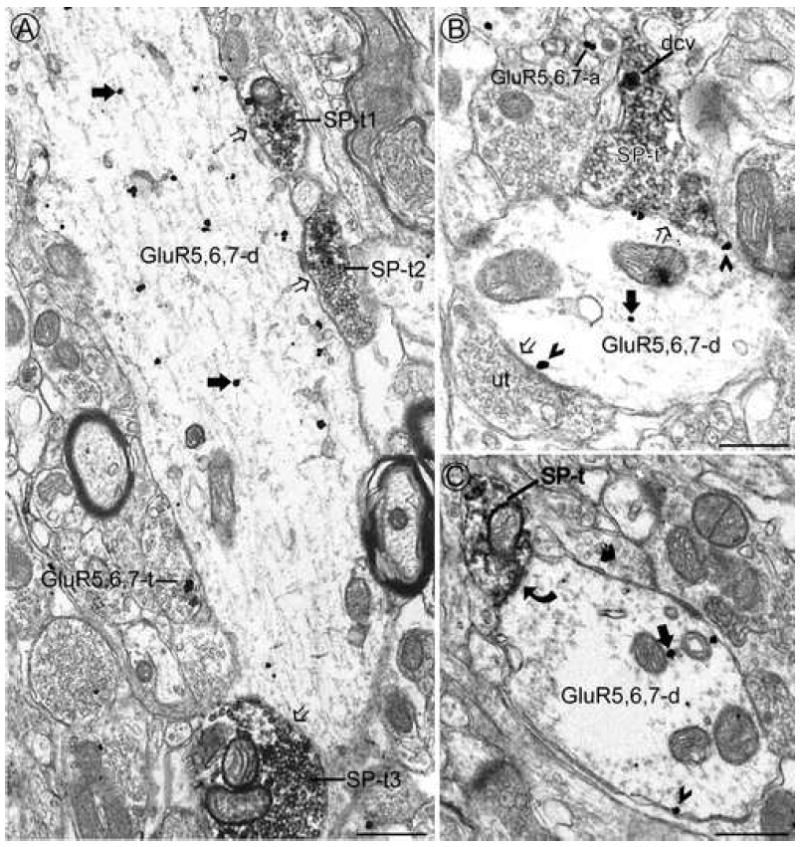

Figure 2.

By electron microscopy, GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was found in dendrites (A, D), axon terminals (B, D), and glia (C). A. Large and small dendritic processes of the same cell (GluR5,6,7-d) contain cytoplasmic (large arrows) and plasmalemmal (arrowheads) immunogold labeling for GluR5,6,7, but a spiny process that receives an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow) from an unlabeled axon terminal (ut) is not labeled. B. A large GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminal (GluR5,6,7-t) contains small, clear vesicles (scv) and forms an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow) with an unlabeled dendrite. Both cytoplasmic (large arrows) and plasmalemmal (arrowheads) GluR5,6,7 immunogold labeling is present. C. An astrocytic glial process with glial filaments (small arrows) contains GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity (GluR5,6,7-glia; large arrow) and surrounds an unlabeled axon terminal (ut) that forms an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow). D. A GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminal (GluR5,6,7-t) forms an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow) with a GluR5,6,7-ir dendrite (GluR5,6,7-d). Scale bar = 0.5 μm.

Figure 3.

By electron microscopy, GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was often found in the dendritic targets of SP-ir axon terminals. A. A large dendrite contains immunogold labeling for GluR5,6,7 at cytoplasmic sites only (large filled arrows). This dendrite receives appositions (open arrows) from several axon terminals containing immunoperoxidase labeling for SP (SP-t1, 2 and 3) and one GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminal (GluR5,6,7-t). B. An axon terminal containing SP (SP-t) in a dense core vesicle (dcv) and an unlabeled terminal (ut) contact a GluR5,6,7-ir dendrite (GluR5,6,7-d). Most of the gold particles are associated with the plasma membrane (arrowheads), particularly along the contact sites with the afferent terminals (open arrows). An immunogold labeled axon (GluR5,6,7-a) is seen in the same field. C. A GluR5,6,7-ir dendrite (GluR5,6,7-d) receives an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow) from an SP-ir axon terminal (SP-t). Gold particles in the GluR5,6,7-ir dendrite are present in the cytoplasm (large arrow) and are associated with the plasma membrane (arrowhead). Scale bar = 0.5 μm.

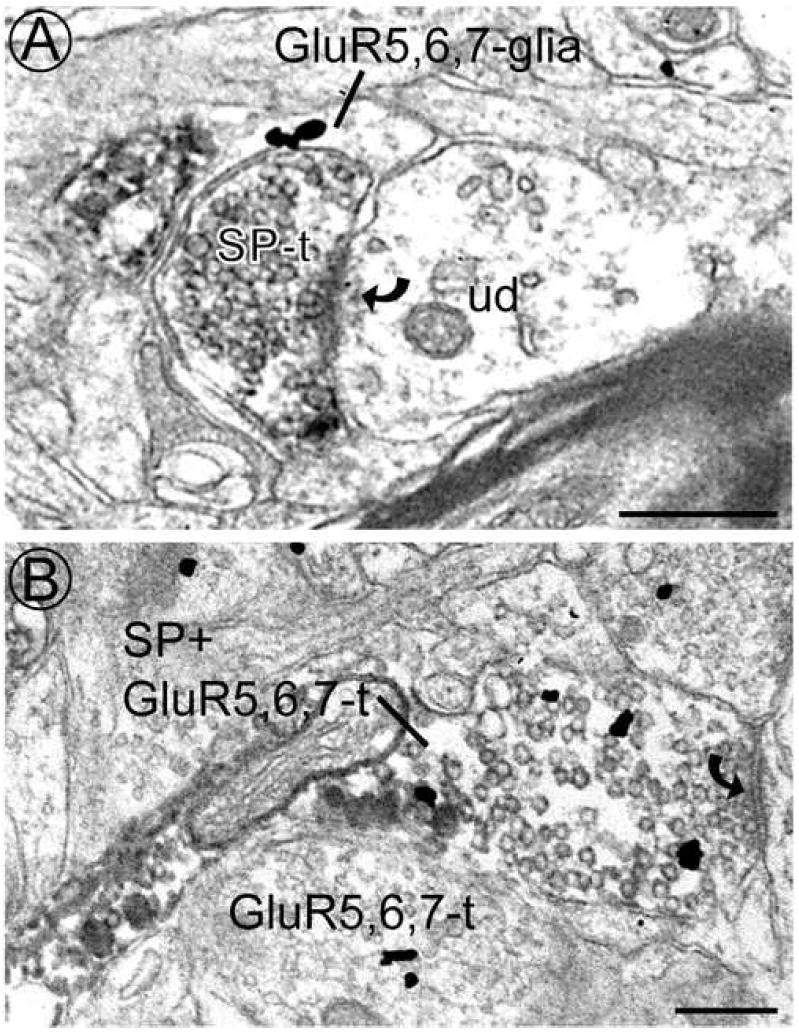

GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was also found at presynaptic sites including unmyelinated axons and axon terminals. GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was associated with small, clear vesicles in axon terminals (Table 1; Fig. 2B,D; 3A) and these GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals primarily formed asymmetric synapses with dendrites (Fig. 2B,D). GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was also associated with glia (Table 1). Many (21%) of the GluR5,6,7-ir glia analyzed (n = 71) were directly apposed to axon terminals making asymmetric synapses with dendrites (Fig. 2C; 4A). Some of the GluR5,6,7-ir glia analyzed contained glial filaments that are characteristic of astrocytes (Fig. 2C) (Peters et al., 1991).

Figure 4.

By electron microscopy, GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was sometimes found in glia and presynaptic SP-ir axon terminals. A. A glial process contains immunogold labeling for GluR5,6,7 (GluR5,6,7-glia) and is directly apposed to an SP-containing axon terminal (SP-t) that forms an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow) with an unlabeled dendrite (ud). B. An axon terminal contains both SP and GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity (SP + GluR5,6,7-t) and forms an asymmetric synapse (curved arrow; far right edge) with an unlabeled dendrite (not shown). An axon terminal containing only immunogold labeling (GluR5,6,7-t) is seen in the same field. Scale bars = 0.5 μm.

Consistent with previous studies, SP immunoreactivity was predominantly localized to axons and axon terminals (Table 1; Fig. 3A-C; 4A). SP-ir axon terminals often made asymmetric synapses with dendrites (Fig. 3C; 4A). There were also a small number of SP-ir somata and dendrites (Table 1), suggesting the presence of SP-ir neurons within the trigeminal dorsal horn.

2.3. Ultrastructural analysis demonstrated the cellular interactions of GluR5,6,7 and SP

The most common interaction observed between SP-ir and GluR5,6,7-ir profiles was presynaptic SP-ir axon terminals contacting postsynaptic GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites (Fig. 3A-C) with 54% of the dendrites contacted by SP-ir axon terminals (n = 260) containing GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity. SP-ir axon terminals often made asymmetric synaptic contacts with GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites (Fig. 3C). In the subset of GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites that received contacts from SP-ir axon terminals in the plane of section analyzed, the average diameter was 1.07 ± 0.05 μm (n = 132; range: 0.25 – 3.25 μm).

There were rare instances of dual-labeled axons in which 4% of the SP-ir axons were also GluR5,6,7-ir (Table 2). We found that 7% of SP-ir axon terminals were also GluR5,6,7-ir and 14% of GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals were also SP-ir (Table 2; Fig. 4B). Of the dendrites contacted by axon terminals that were dual-labeled for SP and GluR5,6,7 (n = 25), 64% were GluR5,6,7-ir. Although less frequent than those labeled with SP, there were also axon terminals that were labeled for GluR5,6,7 alone (Fig. 2B,D; 3A; 4B n = 236). Of the dendrites contacted by these GluR5,6,7-ir terminals (n = 130), 49% were GluR5,6,7-ir (Fig. 2D; 3A) while only 2% were SP-ir. Interestingly, GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites were contacted by dual-labeled axon terminals and GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals at similar frequencies (64% and 49%, respectively) as those contacted by SP-ir axon terminals (54%).

Table 2.

Classification of GluR5,6,7-ir profiles containing SP immunoreactivity and SP-ir profiles containing GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity in trigeminal dorsal horn*

| Antigen | Soma | Dendrites | Axons | Terminals | Glia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GluR5,6,7-ir profiles with SP immunoreactivity | 0/28 (0%) | 10/691 (1%) | 17/403 (4%) | 40/276 (14%) | 0/71 (0%) |

| SP-ir profiles with GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity | 0/3 (0%) | 10/44 (23%) | 17/483 (4%) | 40/552 (7%) | 0/0 (0%) |

Each column in the table indicates the number of dual-labeled profiles in each category, divided by the number of profiles that contained the single antigen indicated (GluR5,6,7 in top row; SP in bottom row). Below this number is the percentage of those profiles that were also immunoreactive for the other antigen.

Although SP-ir dendritic profiles were rare (Table 1), a fair proportion (23%) of these dendrites also contained GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity (Table 2). This observation is similar to our previous findings in which 48% of SP-ir dendrites also contained MOR immunoreactivity (Aicher et al., 2000b). This suggests that SP-ir neurons contained within the trigeminal dorsal horn may be modulated by KAR ligands.

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary

Our primary finding was that KAR subunits were most commonly found postsynaptic to presynaptic axon terminals containing SP in the rat trigeminal dorsal horn. Previous studies have implicated an interactive relationship between SP and glutamate receptors (Dougherty and Willis, 1991; Dougherty et al., 1993; Randic et al., 1993; Rusin et al., 1993), and more specifically, SP and KARs (Mjellem-Joly et al., 1991; Lucifora et al., 2006). However, it was unclear what the exact nature of the relationship was between KARs and SP. Our studies suggest that KARs are primarily involved postsynaptically in the transmission of nociceptive information from the periphery to the central targets of SP-containing afferents.

3.2. Immunocytochemical considerations

In all of our immunocytochemical experiments, we used an antibody that recognizes a common epitope in GluR5, 6 and 7 (Huntley et al., 1993). Although subunit-specific antibodies to GluR5, GluR6/7, KA1 and KA2 exist (Lucifora et al., 2006), the focus of this paper was to determine the overall KAR distribution in the spinal trigeminal subnucleus caudalis. Furthermore, as glutamate activates functional KARs regardless of subunit composition (Pinheiro and Mulle, 2006), we felt that the GluR5,6,7 antibody would best represent the naturally-occurring global KAR distribution in the trigeminal dorsal horn.

3.3. GluR5,6,7 and SP were located in laminae I and II of trigeminal dorsal horn

The light microscopic distributions of GluR5,6,7 and SP immunoreactivities in laminae I and II of trigeminal dorsal horn were consistent with previous studies that used kainate binding site autoradiography and immunocytochemistry to look at KAR and SP distribution in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and Vc area of the trigeminal nucleus (Hokfelt et al., 1975; Ljungdahl et al., 1978; Tallaksen-Greene et al., 1992; Petralia et al., 1994; Aicher et al., 2000a; Hwang et al., 2001; Lucifora et al., 2006). The localization to the spinal and trigeminal dorsal horn supports a role for KARs and the neuropeptide SP in the processing of nociceptive information in the spinal cord and spinal trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (see (Ruscheweyh and Sandkuhler, 2002; Snijdelaar et al., 2000) for review).

3.4. GluR5,6,7 was found pre- and postsynaptically in the trigeminal dorsal horn

The current study quantified the number and characterized the type of profiles that were GluR5,6,7-ir in the trigeminal dorsal horn. GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity was found postsynaptically in dendrites and somata and presynaptically in axons and axon terminals, demonstrating an almost evenly mixed distribution of KARs. A previous study looking at the ultrastructural distribution of GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity in the superficial spinal cord dorsal horn found that, with a weak fixative, a higher percentage of terminals were GluR5,6,7-ir than dendrites (Hwang et al., 2001). When they used a stronger fixative, there was a higher percentage of labeled dendrites as compared to terminals (Hwang et al., 2001). As the Hwang study used different fixation techniques and analyzed fewer labeled profiles, it is not surprising that there are differences between their distribution results and ours. We found that the majority of GluR5,6,7 immunogold particles in dendrites were cytoplasmic, rather than membrane-bound. However, it is reasonable to suggest that cytoplasmic KARs in dendrites would be readily available to insert into relevant membrane sites under different neuronal conditions, such as excitation from presynaptic nociceptive afferents. GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals almost exclusively formed asymmetric synapses with target dendrites, suggesting that KARs may be functioning as autoreceptors for glutamate at those synapses. Therefore, our data support a role for KARs in mediating fast excitatory transmission as well as serving as modulators of glutamate release presynaptically (Frerking and Nicoll, 2000; Kerchner et al., 2001; Kerchner et al., 2002; Jaskolski et al., 2005).

3.5. SP was predominantly distributed presynaptically

The present study demonstrated that SP immunoreactivity was predominantly localized to axons and axon terminals (Table 1). Previous electron microscopic studies in the spinal and trigeminal dorsal horns (Pickel et al., 1977; Aicher et al., 1997) and an immunofluorescence study that included the trigeminal complex (Ljungdahl et al., 1978) support a predominantly presynaptic distribution of SP. There were also rare instances of SP-ir somata and dendrites. Studies suggest that SP may be localized to intrinsic neurons of the spinal cord dorsal horn (Ribeiro-Da-Silva et al., 1991; Ma et al., 1997) which is consistent with our findings of SP-ir somata and dendrites. Although some studies support a role for SP as a neurotransmitter, it is more likely that SP modulates nociception by sensitizing second order spinal neurons and enhancing their response to excitatory input (see (Snijdelaar et al., 2000) for review).

3.6. Postsynaptic GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites were contacted by SP-ir axon terminals as well as dual-label and GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals

Single-label immunocytochemical analysis of KAR subunit localization yields a mixed distribution making it difficult to identify the cellular sites of KAR function, such as primary afferents from the periphery, ascending or descending fibers or interneurons in the dorsal horn. Our electron microscopic results of the distribution of GluR5,6,7-ir and SP-ir profiles support a relationship in which KARs are primarily postsynaptic to nociceptive afferents containing SP. This would suggest that KARs may play a role in mediating the transmission of nociceptive information from SP-containing afferents to supraspinal substrates of the pain pathway.

We also found that of the dendrites contacted by dual-labeled and GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals, 64% and 49%, respectively, of the dendrites were GluR5,6,7-ir. These frequencies are very similar to the frequency of GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites contacted by SP-ir axon terminals (54%). It is interesting that no matter what the presynaptic content, the frequency of GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites contacted by axon terminals containing SP immunoreactivity, GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity or both are not different. It is possible that the subset of SP-ir, GluR5,6,7-ir and dual-labeled axon terminals that target GluR5,6,7-ir dendrites are being segregated by the type of neurons, such as interneurons or output neurons projecting to supraspinal substrates of the pain pathway, that they are contacting. Further studies would be needed to elucidate the type of neurons that SP-ir, GluR5,6,7-ir and dual-labeled axon terminals contact. Another possibility is that there may be more than one type of glutamate receptor present in dendritic targets. For example, a previous study from this lab demonstrated that of the postsynaptic targets contacted by SP-ir axon terminals, 82% of the postsynaptic targets contained the R1 subunit of the NMDAR (Aicher et al., 1997). KARs and NMDARs may colocalize in some dendritic targets and this may play a role in the segregation of axon terminals to certain dendritic targets.

3.7. GluR5,6,7 and SP immunoreactivity colocalized in presynaptic profiles

Although they made up a small number of the total profiles analyzed, presynaptic colocalization of GluR5,6,7 and SP immunoreactivity was evident in axons and axon terminals. Previous studies have found that glutamate and SP colocalize in axon terminals of the spinal cord dorsal horn (De Biasi S. and Rustioni, 1988) and that GluR5-ir DRG neurons in lumbar spinal cord also contained SP immunoreactivity (Lucifora et al., 2006). We found that 7% of SP-ir axon terminals also contained GluR5,6,7 immunoreactivity, while 14% of GluR5,6,7-ir axon terminals contained SP immunoreactivity (Table 2). Colocalization of KARs and SP in presynaptic structures would suggest that KARs function to modulate the release of glutamate from SP-containing afferents. As previous studies have suggested, the co-release of glutamate and SP from axon terminals may synergistically enhance the response of dorsal horn neurons to nociceptive input (Dougherty and Willis, 1991; Dougherty et al., 1993; Randic et al., 1993; Rusin et al., 1993). Therefore, KAR-mediated modulation of glutamate release from SP-containing afferents, may, in turn, modulate the input of the SP-containing afferents to dorsal horn neurons. Considering the number of presynaptic structures that were solely GluR5,6,7-ir (Table 1), we would also suggest that KARs are located on other types of primary afferents that are not necessarily peptidergic. This is in agreement with a previous study that found a high frequency of GluR5-ir DRG neurons were also immunoreactive for P2X3 (Lucifora et al., 2006) which is often found in non-peptidergic afferents.

3.8. GluR5,6,7 was also found in SP-ir dendrites

Although SP-ir dendrites were a small subset of the total number of SP-ir profiles in the dorsal horn, they may represent an important population of neurons for nociceptive processing. A study by Ribeiro-da-Silva and colleagues suggested that SP-ir spinal cord dorsal horn neurons that also contained enkephalin-like immunoreactivity were interneurons that likely received nociceptive input from peripheral afferents and transmitted nociceptive information to supraspinally-projecting neurons (Ribeiro-Da-Silva et al., 1991). We speculate that the SP-ir somata and dendrites detected in the present study may represent these nociceptive-responsive interneurons. In the present study we found that 23% of these SP-ir dendrites contained GluR5,6,7-ir (Table 2), an observation comparable to our previous finding of colocalization between SP and MOR1 (Aicher et al., 2000b). As in the previous study, our results suggest that a subset of the SP-ir interneurons may frequently be modulated by KAR ligands. Therefore, the current anatomical study supports a role for KARs as mediators of excitatory neuronal transmission and modulators of nociceptive transmission within SP-containing afferents and interneurons in the trigeminal dorsal horn.

4. Experimental procedure

4.1. Subjects and perfusion

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River laboratories, Wilmington, MA; 250 – 350 g; n = 11) were used in these studies. Each rat was overdosed with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially through the ascending aorta with the following sequence of solutions: (1) 10 ml of heparinized saline (1000 units/ml); (2) 50 ml of 3.8% acrolein in 2% paraformaldehyde, and (3) 200 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4) (Aicher et al., 2003; Zeng et al., 2006). The caudal brainstem was removed and placed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, then placed in PB. Blocks of caudal brainstem tissue were sectioned (40μm) on a vibrating microtome (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL). The sectioned tissue was then processed for the appropriate immunocytochemical procedures (see below). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health & Science University.

4.2. Immunocytochemistry for light microscopy

Immunocytochemistry was performed as previously demonstrated (Aicher et al., 2000a; Aicher et al., 2003). Sections were incubated in 1% sodium borohydride in PB for 30 minutes to increase antigenicity and then in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.1M Tris-buffered saline (TS) for 30 minutes to reduce non-specific binding. The tissue was then incubated in either a monoclonal rat IgG primary antibody directed against the C-terminal region of SP (1:1000; Accurate Chemical and Scientific, Westbury, NY) or a monoclonal mouse ascites IgM primary antibody directed against the N-terminal region of kainate receptor (KAR) subunits GluR5, 6 and 7 (GluR5,6,7) (1:800; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) with 0.25% Triton-X and 0.1% BSA in 0.1M TS for 40 hours at 4°C. The monoclonal antibodies directed against SP and GluR5,6,7 have previously been characterized and examined for specificity using radioimmunoassay (Cuello et al., 1979), Western blot (Huntley et al., 1993) and preadsorption immunocytochemistry controls (Cuello et al., 1979; Huntley et al., 1993). Bound primary antibody was visualized by incubating tissue sections in biotinylated donkey α rat IgG (1:400; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or biotinylated donkey α mouse IgM (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) secondary antibody followed by incubation in Avidin-Biotin (Elite Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories) and diaminobenzidine-hydrogen peroxidase (DAB-H2O2) solutions. The species of the primary and secondary antibodies were selected so that no cross-reactivity would occur. Control cases with mismatch between the primary and secondary antibody yielded no labeling. Tissue was mounted on gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated and then coverslipped with DPX mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Representative images were taken with an Olympus DP71 digital camera (Melville, NY) mounted onto an Olympus BX51 microscope.

4.3. Dual-label immunocytochemistry for electron microscopy

Tissue sections to be used for electron microscopic analysis were processed using combined immunoperoxidase and colloidal gold immunocytochemical methods (Chan et al., 1990; Aicher et al., 2003; Zeng et al., 2006). The freeze-thaw method was used to increase antibody penetration of the tissue, and the sections were then incubated in 0.1% sodium borohydride in 0.1M TS and 0.5% BSA in 0.1M TS. In one set of experiments, tissue sections were then incubated in a cocktail of the monoclonal primary antibodies directed against SP (1:1000; Accurate) and GluR5,6,7 (1:75; BD Pharmingen) for 48 hours at 4°C. Bound SP primary antibody was visualized by incubating tissue sections in biotinylated donkey anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch) followed by incubation in Avidin-Biotin (Elite Vectastain ABC kit) and diaminobenzidine-hydrogen peroxidase (DAB-H2O2) solution. To visualize the GluR5,6,7 primary antibody, the tissue was incubated in colloidal gold-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody (1:50; Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Hatfield, PA) for 2 hours. In another set of experiments the immunoperoxidase and immunogold markers were reversed. In these cases, the primary antibody concentrations were 1:200 for SP and 1:750 for GluR5,6,7. The SP primary antibody was then visualized by incubating the tissue sections in colloidal gold-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (1:50; EMS) and the GluR5,6,7 primary antibody was visualized with a biotinylated donkey anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch) as described above. In both sets of experiments the tissue sections were then fixed in 2% EM grade glutaraldehyde (EMS) and the gold particles were enhanced with the Amersham IntenSE™ M silver enhancement kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Tissue sections were osmicated (1 hour; 2% osmium tetroxide), dehydrated through ethanols and propylene oxide and then incubated in a 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide and EMBed 812 (EMS) overnight. The following day, the sections were embedded in EMBed 812 between two sheets of Aclar flurohalocarbon plastic film (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) and then placed in an oven for 48 hours at 60°C. Regions of tissue containing both SP and GluR5,6,7 labeling were selected from the ventrolateral region of the spinal trigeminal subnucleus caudalis and were glued onto Beem capsules (Ted Pella), sectioned at 75nm on a Leica Microsystems ultramicrotome, collected onto 400 mesh copper grids (EMS) and counterstained with uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate.

4.4. Data analysis for electron microscopy

Ultrathin sections were examined on a Morgagni electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) and images were captured digitally on an Advanced Microscopy Techniques (AMT; Danvers, MA) 2K × 2K camera. The selection of ultrathin sections for EM analysis was based on optimal preservation of morphological details and maximal detection of the labeling (Peters et al., 1991). Sections were selected from an area just below the surface of the tissue, at the tissue/plastic interface, where the penetration of antibodies was optimal in order to avoid under detection of the immunogold antigen (Chan et al., 1990; Aicher et al., 2003). Analysis was focused on the superficial laminae (I and II) of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis in which SP-labeled primary afferents are confined (Jessell and Iversen, 1977; Priestley et al., 1982; Aicher et al., 2000a). Regions of tissue had to contain both immunogold and immunoperoxidase-labeled profiles that were within 25 μm of each other in order to be included in this study (Aicher et al., 2003).

Images were assessed for the type of profile (i.e., perikarya, dendrites, terminals, axons or glia) labeled with either immunoperoxidase, immunogold or both (Peters et al., 1991). Images were also assessed for the type of synaptic input to labeled perikarya or dendrites (symmetric or asymmetric) or the type of synapse formed by labeled terminals (Peters et al., 1991). In order for a profile to be considered positive for immunogold labeling, two or more gold particles had to be present in perikarya, dendrites, terminals and glia. In unmyelinated axons, the criterion was at least one gold particle associated with the plasmalemmal surface (Aicher et al., 2003). Immunogold labeled profiles were further analyzed for the distribution of gold particles on the plasmalemmal surface compared to intracellular membrane sites (Drake et al., 2005). All micrographs analyzed were initially calibrated to their respective scale bars.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Charles Meshul for the use of his electron microscopy facilities at the Portland VA Medical Center. Special thanks to Sam Hermes for his helpful review of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to S.A.A. from NIH (DE12640; HL56301).

References

- Advokat C, Rutherford D. Selective antinociceptive effect of excitatory amino acid antagonists in intact and acute spinal rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:855–860. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrah AW, Fiska A, Gjerstad J, Gustafsson H, Tjolsen A, Olgart L, Stiller CO, Hole K, Brodin E. Spinal substance P release in vivo during the induction of long-term potentiation in dorsal horn neurons. Pain. 2002;96:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher SA, Mitchell JL, Swanson KC, Zadina JE. Endomorphin-2 axon terminals contact mu-opioid receptor-containing dendrites in trigeminal dorsal horn. Brain Res. 2003;977:190–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02678-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher SA, Punnoose A, Goldberg A. mu-Opioid receptors often colocalize with the substance P receptor (NK1) in the trigeminal dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2000a;20:4345–4354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04345.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher SA, Sharma S, Cheng PY, Liu-Chen LY, Pickel VM. Dual ultrastructural localization of mu-opiate receptors and substance p in the dorsal horn. Synapse. 2000b;36:12–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200004)36:1<12::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher SA, Sharma S, Cheng PY, Pickel VM. The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor is postsynaptic to substance P-containing axon terminals in the rat superficial dorsal horn. Brain Res. 1997;772:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen BJ, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Menning PM, Kuskowski MA, Basbaum AI, Simone DA, Mantyh PW. Noxious cutaneous thermal stimuli induce a graded release of endogenous substance P in the spinal cord: imaging peptide action in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5921–5927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber RP, Vaughn JE, Slemmon JR, Salvaterra PM, Roberts E, Leeman SE. The origin, distribution and synaptic relationships of substance P axons in rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1979;184:331–351. doi: 10.1002/cne.901840208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Rustioni A. Coexistence of glutamate and substance P in dorsal root ganglion neurons of the rat and monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1988;277:302–312. doi: 10.1002/cne.902770210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn-Munro G, Bomholt SF, Erichsen HK. Behavioural effects of the novel AMPA/GluR5 selective receptor antagonist NS1209 after systemic administration in animal models of experimental pain. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodin E, Linderoth B, Gazelius B, Ungerstedt U. In vivo release of substance P in cat dorsal horn studied with microdialysis. Neurosci Lett. 1987;76:357–362. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt NA, Stiller C, Gustafsson H, Malmberg AB. Elevated substance-P-like immunoreactivity levels in spinal dialysates during the formalin test in normal and diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2000;856:20–27. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YQ, Mantyh PW, Carlson EJ, Gillespie AM, Epstein CJ, Basbaum AI. Primary afferent tachykinins are required to experience moderate to intense pain. Nature. 1998;392:390–394. doi: 10.1038/32897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Aoki C, Pickel VM. Optimization of differential immunogold-silver and peroxidase labeling with maintenance of ultrastructure in brain sections before plastic embedding. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;33:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall RE, Carlton SM. Ultrastructural analysis of NMDA, AMPA, and kainate receptors on unmyelinated and myelinated axons in the periphery. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:78–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980202)391:1<78::aid-cne7>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello AC, Galfre G, Milstein C. Detection of substance P in the central nervous system by a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:3532–3536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi S, Rustioni A. Glutamate and substance P coexist in primary afferent terminals in the superficial laminae of spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7820–7824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKoninck Y, Ribeiro-Da-Silva A, Henry JL, Cuello AC. Spinal neurons exhibiting a specific nociceptive response receive abundant substance P-containing synaptic contacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5073–5077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty PM, Palecek J, Zorn S, Willis WD. Combined application of excitatory amino acids and substance P produces long-lasting changes in responses of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:227–246. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90003-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty PM, Willis WD. Enhancement of spinothalamic neuron responses to chemical and mechanical stimuli following combined micro-iontophoretic application of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid and substance P. Pain. 1991;47:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90015-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Aicher SA, Montalmant FL, Milner TA. Redistribution of mu-opioid receptors in C1 adrenergic neurons following chronic administration of morphine. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubner R, Bennett GJ. Spinal and trigeminal mechanisms of nociception. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1983;6:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.06.030183.002121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan AW, Hendry IA, Morton CR, Hutchison WD, Zhao ZQ. Cutaneous stimuli releasing immunoreactive substance P in the dorsal horn of the cat. Brain Res. 1988;451:261–273. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90771-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerking M, Nicoll RA. Synaptic kainate receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:342–351. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeazza MT, Garry MG, Yost HJ, Strait KA, Hargreaves KM, Seybold VS. Plasticity in the synthesis and storage of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in primary afferent neurons during peripheral inflammation. Neuroscience. 1995;66:443–458. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00545-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VL, Yaksh TL. Release of substance P from the cat spinal cord. J Physiol. 1987;391:141–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokfelt T, Kellerth JO, Nilsson G, Pernow B. Substance p: localization in the central nervous system and in some primary sensory neurons. Science. 1975;190:889–890. doi: 10.1126/science.242075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore P, Menning PM, Rogers SD, Nichols ML, Basbaum AI, Besson JM, Mantyh PW. Spinal substance P receptor expression and internalization in acute, short-term, and long-term inflammatory pain states. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7670–7678. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07670.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner JE. Glutamate receptor channels in rat DRG neurons: activation by kainate and quisqualate and blockade of desensitization by Con A. Neuron. 1990;5:255–266. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90163-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley GW, Rogers SW, Moran T, Janssen W, Archin N, Vickers JC, Cauley K, Heinemann SF, Morrison JH. Selective distribution of kainate receptor subunit immunoreactivity in monkey neocortex revealed by a monoclonal antibody that recognizes glutamate receptor subunits GluR5/6/7. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2965–2981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-02965.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins B, Spears R, Hinton RJ, Harper RP. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P immunoreactivity in rat trigeminal ganglia and brainstem following adjuvant-induced inflammation of the temporomandibular joint. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(99)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Pagliardini S, Rustioni A, Valtschanoff JG. Presynaptic kainate receptors in primary afferents to the superficial laminae of the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:275–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskolski F, Coussen F, Mulle C. Subcellular localization and trafficking of kainate receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell T, Tsunoo A, Kanazawa I, Otsuka M. Substance P: depletion in the dorsal horn of rat spinal cord after section of the peripheral processes of primary sensory neurons. Brain Res. 1979;168:247–259. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell TM, Iversen LL. Opiate analgesics inhibit substance P release from rat trigeminal nucleus. Nature. 1977;268:549–551. doi: 10.1038/268549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Wilding TJ, Huettner JE, Zhuo M. Kainate receptor subunits underlying presynaptic regulation of transmitter release in the dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8010–8017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08010.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Wilding TJ, Li P, Zhuo M, Huettner JE. Presynaptic kainate receptors regulate spinal sensory transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:59–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuraishi Y, Hirota N, Sato Y, Hanashima N, Takagi H, Satoh M. Stimulus specificity of peripherally evoked substance P release from the rabbit dorsal horn in situ. Neuroscience. 1989;30:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Fields HL, Basbaum AI. Peptides and the primary afferent nociceptor. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2273–2286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Wilding TJ, Kim SJ, Calejesan AA, Huettner JE, Zhuo M. Kainate-receptor-mediated sensory synaptic transmission in mammalian spinal cord. Nature. 1999;397:161–164. doi: 10.1038/16469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungdahl A, Hokfelt T, Nilsson G. Distribution of substance P-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the rat--I. Cell bodies and nerve terminals. Neuroscience. 1978;3:861–943. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucifora S, Willcockson HH, Lu CR, Darstein M, Phend KD, Valtschanoff JG, Rustioni A. Presynaptic low- and high-affinity kainate receptors in nociceptive spinal afferents. Pain. 2006;120:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Ribeiro-Da-Silva A, De KY, Radhakrishnan V, Cuello AC, Henry JL. Substance P and enkephalin immunoreactivities in axonal boutons presynaptic to physiologically identified dorsal horn neurons. An ultrastructural multiple-labelling study in the cat. Neuroscience. 1997;77:793–811. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcangio M, Ramer MS, Jones MG, McMahon SB. Abnormal substance P release from the spinal cord following injury to primary sensory neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:397–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarson KE, Goldstein BD. Release of substance P into the superficial dorsal horn following nociceptive activation of the hindpaw of the rat. Brain Res. 1991;568:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91385-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mjellem-Joly N, Lund A, Berge OG, Hole K. Potentiation of a behavioural response in mice by spinal coadministration of substance P and excitatory amino acid agonists. Neurosci Lett. 1991;133:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasstrom J, Karlsson U, Post C. Antinociceptive actions of different classes of excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;212:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90067-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubert JK, Maidment NT, Matsuka Y, Adelson DW, Kruger L, Spigelman I. Inflammation-induced changes in primary afferent-evoked release of substance P within trigeminal ganglia in vivo. Brain Res. 2000;871:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T, Gyermek L, Lee C, Kawasaki-Yatsugi S, Yamaguchi T. The spinal antinociceptive effects of a novel competitive AMPA receptor antagonist, YM872, on thermal or formalin-induced pain in rats. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:143–147. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199907000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano K, Kuraishi Y, Satoh M. Involvement of spinal substance P and excitatory amino acids in inflammatory hyperalgesia in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;76:15–22. doi: 10.1254/jjp.76.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HD. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System: Neurons and Their Supporting Cells. Oxford, New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Wang YX, Wenthold RJ. Histological and ultrastructural localization of the kainate receptor subunits, KA2 and GluR6/7, in the rat nervous system using selective antipeptide antibodies. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:85–110. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Reis DJ, Leeman SE. Ultrastructural localization of substance P in neurons of rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1977;122:534–540. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro P, Mulle C. Kainate receptors. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:457–482. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestley JV, Somogyi P, Cuello AC. Immunocytochemical localization of substance P in the spinal trigeminal nucleus of the rat: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1982;211:31–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.902110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randic M, Jiang MC, Rusin KI, Cerne R, Kolaj M. Interactions between excitatory amino acids and tachykinins and long-term changes of synaptic responses in the rat spinal dorsal horn. Regul Pept. 1993;46:418–420. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90106-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Da-Silva A, Pioro EP, Cuello AC. Substance P- and enkephalin-like immunoreactivities are colocalized in certain neurons of the substantia gelatinosa of the rat spinal cord: an ultrastructural double-labeling study. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1068–1080. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-01068.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Role of kainate receptors in nociception. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusin KI, Jiang MC, Cerne R, Randic M. Interactions between excitatory amino acids and tachykinins in the rat spinal dorsal horn. Brain Res Bull. 1993;30:329–338. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara Y, Noro N, Iida Y, Soma K, Nakamura Y. Glutamate receptor subunits GluR5 and KA-2 are coexpressed in rat trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6611–6620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsam M, Covenas R, Ahangari R, Yajeya J, Narvaez JA, Tramu G. Alterations in neurokinin A-, substance P- and calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivities in the caudal trigeminal nucleus of the rat following electrical stimulation of the trigeminal ganglion. Neurosci Lett. 1999;261:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00989-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible HG, Ebersberger A, Peppel P, Beck U, Messlinger K. Release of immunoreactive substance P in the trigeminal brain stem nuclear complex evoked by chemical stimulation of the nasal mucosa and the dura mater encephali--a study with antibody microprobes. Neuroscience. 1997;76:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible HG, Jarrott B, Hope PJ, Duggan AW. Release of immunoreactive substance P in the spinal cord during development of acute arthritis in the knee joint of the cat: a study with antibody microprobes. Brain Res. 1990;529:214–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RM, Li DL, Hoo KH, Deverill M, Ornstein PL, Iyengar S. Kainate GluR5 receptor subtype mediates the nociceptive response to formalin in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluka KA, Dougherty PM, Sorkin LS, Willis WD, Westlund KN. Neural changes in acute arthritis in monkeys. III. Changes in substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide and glutamate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1992;17:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(92)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijdelaar DG, Dirksen R, Slappendel R, Crul BJ. Substance P. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:121–135. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto T, Fujiyoshi Y, Xiao C, He YF, Ichikawa H. Central projection of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)- and substance P (SP)-immunoreactive trigeminal primary neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378:425–442. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970217)378:3<425::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekely JI, Kedves R, Mate I, Torok K, Tarnawa I. Apparent antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of GYKI 52466. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;336:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallaksen-Greene SJ, Young AB, Penney JB, Beitz AJ. Excitatory amino acid binding sites in the trigeminal principal sensory and spinal trigeminal nuclei of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1992;141:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WD. The Pain System: The Neural Basis of Nociceptive Transmission in the Mammalian Nervous System. Karger, Paris: 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Jessell TM, Gamse R, Mudge AW, Leeman SE. Intrathecal morphine inhibits substance P release from mammalian spinal cord in vivo. Nature. 1980;286:155–157. doi: 10.1038/286155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Michener SR, Bailey JE, Harty GJ, Lucas DL, Nelson DK, Roddy DR, Go VL. Survey of distribution of substance P, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, cholecystokinin, neurotensin, Met-enkephalin, bombesin and PHI in the spinal cord of cat, dog, sloth and monkey. Peptides. 1988;9:357–372. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(88)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Thomson LM, Aicher SA, Terman GW. Primary Afferent NMDA Receptors Increase Dorsal Horn Excitation and Mediate Opiate Tolerance in Neonatal Rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12033–12042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2530-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]