Abstract

Recently, we have shown that UGT1A10 is actively involved in the inactivation of E1, E2, and their 2- and 4-hydroxylated derivatives. In the present study, we show for the first time that treatment of the MCF-7 ER-positive breast cancer cell line with E2 produces a dose-dependent up-regulation of UGT1A10 mRNA levels, followed by a steady down-regulation. In contrast, E2 did not stimulate mRNA expression in the MDA-MB-231 (ER)-negative breast cancer cell line. Expression of UGT1A10 mRNA was blocked by the antiestrogen, ICI 182,780, but not by the transcriptional inhibitor, actinomycin-D. These findings suggest that regulation of UGT1A10 mRNA might be a primary transcriptional response mediated through the ER. Expression of UGT1A10 mRNA was also stimulated by other estrogenic compounds including propylpyrazoletriol (PPT) and genistein (Gen). Exposure of MCF-7 cells to 0.1 nM E2 up-regulated, and then down-regulated, UGT1A protein and enzymatic activity toward E2 at 10 nM E2 as determined by Western blot and glucuronidation activity assays. Collectively, these results suggest that induction of UGT1A10 mRNA expression by E2 might be mediated through ER, and that this isoform is a novel, estrogen regulated target gene in MCF-7, ER-positive human breast cancer cells. The finding of E2-induced expression of UGT1A10 mRNA, followed by the down-regulation of UGT1A10 at pharmacological concentrations of E2, might have a significant moderating effect on E2 availability for ER and estrogen clearance, thereby promoting the signaling of E2 in breast cancer cells.

Keywords: UGTs, UGT1A10, estradiol (E2), steroid, breast cancer, estrogen receptor (ER)

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen exposure is essential for the function and regulation of the female reproductive system, and for the development of female secondary sex characteristics. In the breast, estrogens stimulate the growth and differentiation of the ductal epithelium, induce mitotic activity of ductal cylindric cells, and stimulate the growth of connective tissue [1]. Moreover, estrogens can stimulate the growth of breast cancer cells [1,2]. The two most potent endogenous estrogens, estrone (E1) and 17β-estradiol (E2), are both ligands for estrogen receptors (ER). These receptors have a higher affinity for E2 than for E1, and E2 is believed to be the predominant endogenous activator of ER-mediated cellular processes [3,4]. ER-mediated cellular events occur in estrogen target tissues when an excess of free extracellular E2 or other estrogenic ligand diffuses across the cell membrane and binds an ER. ER undergoes a conformational change to displace the heat shock protein (hsp) which encourages dimerization and tight binding of ER to its specific DNA target, the estrogen response element (ERE) [5]. The activated estrogen-ER complex can interact with cofactors that modify ER action either by enhancing (coactivators) or inhibiting (corepressors) target gene transcription [6]. This process results in the production of mRNAs that are translated to proteins that regulate many cellular processes [7,8]. In general, the regulation of estrogens in the breast is dependent upon many factors including the action of E2 via ER and the activity of steroidogenic enzymes involved in the production and metabolism of estrogens.

Glucuronidation, catalyzed by UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), is an important process of metabolism and detoxification of estrogens. UGTs are membrane-bound glycoproteins localized in the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope [9]. UGTs are defined by their ability to catalyze the transfer of glucuronic acid from the co-substrate UDP-glucuronic acid (UDP-GA) to a wide range of hydrophobic endogenous and exogenous substrates generating more polar, generally inactive molecules that can be readily excreted from the body in the urine or bile [10,11]. However, UGTs can also generate bioactive, perhaps toxic compounds, including those of steroid hormones, morphine, retinoids, and bile acids [12-16].

UGTs have been classified into two families, UGT1 and UGT2, based on the similarity of their primary amino acid sequences [17]. The UGT1 isoforms in humans are encoded by a single gene locus consisting of several first exons that are independently spliced to four common exons (2−5), resulting in enzymes with unique N-terminal domains and identical C-terminal domains [18]. The UGT1A isoforms display broad substrate specificity and are expressed predominantly in the liver, but are also found in extrahepatic tissues [17,19]. In contrast to the UGT1 family, the individual UGT2 genes each comprise six exons that are not shared between the UGT2 family members [20]. The UGT2B isoforms conjugate many compounds including bile acids, steroid hormones, and xenobiotics [21]. Because several UGT1A and UGT2B isoforms conjugate substrates that bind nuclear receptors, it has been suggested that these enzymes play a role in controlling their steady state concentrations for nuclear receptors and thereby maintain homeostasis of the cell [22].

Recently, UGT1A10 has been identified as the major UGT that conjugates estrogens and/or their hydroxylated metabolites [23,24]. Human UGT1A10 is highly expressed in several tissues of the gastrointestinal tract (biliary tract, colon, stomach, and duodenum) [25]. As yet unpublished data from our laboratory have shown that UGT1A10 is also expressed and functional in human breast tissues. UGT1A10 is highly homologous to UGT1A7 and UGT1A8 and all belong to the UGT1A7−10 cluster of UGT1A genes that share sequence similarities of approximately 90% [26]. UGT1A10 is known to conjugate estrogens, bioflavonoids, phenols, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are carcinogenic [25]. The identification of UGT1A10 in conjugating estrogens and its expression in human breast tissues and cells is a novel finding.

Recently, UGT2B15, a UGT involved in the glucuronidation of steroids and xenobiotics was identified as a novel, estrogen-regulated gene in ER-positive human breast cancer cell lines, including MCF-7. Therefore, we hypothesized that UGT1A10, the major estrogen-conjugating UGT, might also be regulated by estrogens. In the present study, we investigated the effects of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA expression in the human breast adenocarcinoma cell lines, MCF-7, which express ERα/β, and MDA-MB-231, which lacks ER and expression. We demonstrated that UGT1A10 mRNA expression is stimulated, and then decreased, by E2 in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Furthermore, we postulate that this dose- and time-dependent regulation of UGT1A10 by E2 might be mediated via the ER. This study shows for the first time, that UGT1A10 is an estrogen target gene. The finding of E2-induced expression of UGT1A10 mRNA might have an effect on E2 availability for ER, thereby regulating E2 signaling in estrogen-responsive breast cancer. The down-regulation of UGT1A10 at pharmacological concentrations of E2 might have a significant moderating effect on estrogen clearance, thereby promoting the signaling of E2 in breast cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

[14C]UDP-glucuronic acid was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA). Estradiol (E2), genistein (Gen), actinomycin-D, cycloheximide (CHX), propylpyrazoletriol (PPT), and saccharolactone (saccharic acid-1,4-lactone) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The antiestrogen, ICI 182,780, was supplied by ICI Pharmaceuticals (Macclesfield, England, Lot #C42710). All other chemicals and solvents were of the highest quality commercially available.

Cell Culture

All cell lines used in these studies were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The human breast cancer cell line that expresses both ERα/β, MCF-7 (ATCC No. HTB-22), and the human ER-negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 (ATCC No. HTB-26), were routinely maintained in MEM medium supplemented with 5% FBS. Six days before harvesting, cells to be treated were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with phenol red-free MEM containing 5% charcoal dextran (CD)-treated FBS to strip the medium of any estrogens. Cells were treated with estrogens (E2, PPT and Gen), antiestrogen (ICI 182,780), and the translational inhibitor, CHX, at concentrations given in the legends for Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5. All treatment groups were harvested at the same time, and total RNA was prepared using the Qiagen RNA Isolation kit (Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In transcription inhibitition assays, actinomycin-D (1 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium together with vehicle, E2, PPT, or Genistein, and mRNA was collected at various time points, as shown in Figure 6. All experiments were performed at least three times.

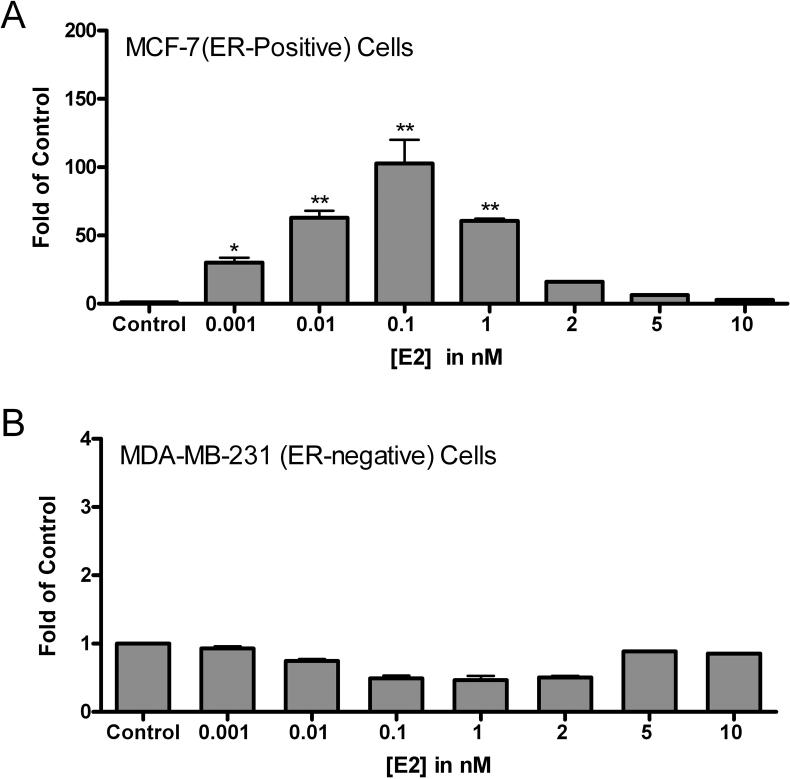

Figure 2. Effect of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA expression in MCF-7 (ER-positive) and MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative) breast cancer cell lines.

(A) MCF-7 (ER-positive) or (B) MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative) breast cells were treated with vehicle (control) or E2 at concentrations ranging from 1 pM to 10 nM for 8 h. UGT1A10 mRNA expression was analyzed by QRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the ratio of mRNA in treated cells to that in control cells treated with vehicle (fold change from control). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 (as compared to control) are considered significant. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 3. Effect of E2 on UGT2B15 and UGT2B7 mRNA expression.

MCF-7 cells were treated with ethanol (control) and concentrations of E2 ranging from 1 pM to 10 nM for 8 h. UGT2B15 and 2B7 mRNA expression was analyzed by QRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the ratio of mRNA in treated cells to that in control cells treated with vehicle (fold change from control). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared to control is significant. Values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 4. Effect of ER agonists and an antagonist on UGT1A10 mRNA levels in MCF-7 cells.

MCF-7 cells were treated with varying concentrations of (A) Propylpyrazoletriol (PPT), an ER α selective agonist, (B) genistein (Gen), an ER agonist, agonist, or (C) ICI 182,780 (ICI), an antiestrogen, for 8 hrs to determine maximum induction of UGT1A10 mRNA levels. UGT1A10 mRNA expression was analyzed by QRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the ratio of mRNA in treated cells to that in control cells treated with vehicle (fold change from control). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 (as compared to control) are considered significant. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 5. Effect of E2, ICI, actinomycin-D, and cycloheximide on UGT1A10 mRNA levels.

(A) MCF-7 cells were treated with ethanol (control), E2 (0.1 nM), or a combination of E2 for 8 h after a 2-h pretreatment with ICI (1 μM). (B) MCF-7 cells were treated with ethanol (control), E2 (0.1 nM) in the presence or absence of actinomycin-D (1μg/mL) or after a 2-h pretreatment with cycloheximide (CHX) (10 nM). UGT1A10 mRNA expression was analyzed by QRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the ratio of mRNA in treated cells to that in control cells (fold change from control). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 are considered significant compared to control. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments

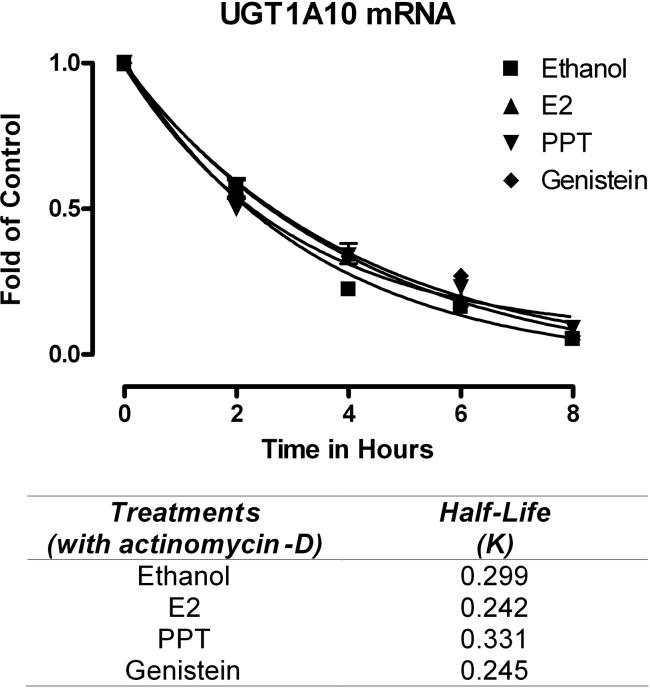

Figure 6. Analysis of UGT1A10 mRNA stability in MCF-7 cells.

Stability of UGT1A10 mRNA was analyzed by addition of actinomycin-D (1 μg/ml). Total RNA was extracted at various time points, and RT-PCR of UGT1A10 mRNA was performed. Plotted data are expressed as the percentage of mRNA remaining and are representative of three independent experiments. The half-life of UGT1A10 mRNA in actinomycin-D-treated cells was calculated by fitting the percentage of mRNA remaining versus time data with a one-phase exponential decay equation using GraphPad Prism 4. (Y = span · e–K*X + plateau, where X = time, and Y = % mRNA remaining. Y = span + plateau at X = 0 and decreases to plateau with a rate constant, K. The half-life for the decay for ethanol, E2, PPT, and genistein is 0.299, 0.242, 0.331, 0.245/K, respectively.

cDNA Synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR)

cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the Clontech cDNA kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Briefly, total RNA (2 μg) from cells was reverse transcribed in a final volume of 20 μl containing 5 × RT-PCR buffer, 10 mM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 40 units/μL of recombinant RNase inhibitor, 200 units/μL of MMLV reverse transcriptase, and 20 μM random hexamers. Samples were incubated at 42 °C for 60 min., reverse transcriptase was inactivated by heating at 70°C for 5 min and cooling at 4°C for 1 min. QRT-PCR reactions were performed in a volume of 50 μl containing 50 ng cDNA, 20 μM primers, deionized water, and 25 μl SYBR Green Master Mix (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX) using the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Optical data were collected during the 60 °C step. PCRs were carried out in 96-well thin-wall PCR plates covered with optically clear sealing film (Applied Biosystems). Amplification, detection, and data analysis were performed using the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detector system (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR primer sequences for the detection of UGT1A10, UGT2B7, UGT2B15, and GAPDH were obtained from Congiu et al. [27]. Sequences of those primers were selected from UGT sequences aligned using DNAMAN software (Lynnon corporation, Quebec, Canada). For the detection of all family 1 isoforms, primers were made to regions spanning exons 3 and 4 and, for the detection of all known family 2 isoforms, to regions spanning exons 1 to 3. For each pair of primers, the control without reverse transcriptase was also used for PCR reactions in triplicate to confirm that there was no genomic DNA contamination in the cDNA samples. Specificity of the primers was determined by analysis of PCR products, which were of the correct size, as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis.

To construct standard curve for each gene of interest, cDNA was diluted to 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 ng and were amplified with specific primers along with the samples. A standard graph was constructed using the “crossing point” value obtained during the amplification of each diluted cDNA. After the PCR amplification was over, melting curve analysis was done on the amplified products to delineate the primer dimer formation.

Results were expressed using the comparative threshold, ΔCt, method after validation, following the recommendations of the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). Specifically, the amount of target mRNA relative to GAPDH mRNA was expressed as 2−(ΔΔCt). The mRNA levels of UGT1A10, UGT2B7 and UGT2B15 were normalized according to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels and expressed as a ratio of the control level. All PCR reactions were performed in triplicate in three independent experiments.

Membrane Preparation

Briefly, frozen MCF-7 breast cancer cells were disrupted by sonication in sample buffer (0.25 M sucrose, HEPES, and protease inhibitors), followed by centrifugation at 2,300 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. Cells were then suspended in sample buffer and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g at 4 °C for 60 min. The final membrane pellet was suspended in sample buffer and stored at −80 °C until use. Protein content of the microsomal fractions was determined using a kit from BioRad (Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin (fraction V, Sigma) as standard.

Western Blot Analysis

Microsomal protein (10 μg) from E2-treated or ethanol vehicle (control)-treated MCF-7 cells were boiled for 5 minutes, separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane following the method of Towbin [27]. The blotted membrane was blocked with 5% fat-free dry milk for at least 2 h at room temperature and incubated with an anti-UGT1A antibody (1:500, Gentest, San Jose, CA) at 4 °C overnight. This antibody recognizes all UGTs isoforms from the UGT1A family. An antibody specific for UGT1A10 is not available. After washing to remove primary antibody, the membrane was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Sigma; 1:10,000). The membrane was rinsed and immunoreactive protein was detected by reaction for 1 min with SuperSignal West Femto chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL) followed by exposure to X-ray film at room temperature for 15 s to 1 min.

Glucuronidation Activity Assays

MCF-7 cells treated with ethanol vehicle (control), 0.1 nM E2, or 10 nM E2 were used for UGT glucuronidation assays. Incubations contained microsomal protein (10 μg), 5 μl of buffer (6 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 30 mM MgCl2, 30 mM saccharolactone), DMSO (2% final concentration), and 250 μM E2 in a total volume of 30 μl. Controls omitting substrate were run with each assay. Reactions were initiated by adding [14C]UDP-GlcUA, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and terminated by adding 30 μl ethanol, and cooled on ice. Identification and quantitation of glucuronides formed were done as previously described [28].

Data Analysis

Results from QRT-PCR and steroid glucuronidation activity assays are shown as the mean ± SEM. Differences between ethanol vehicle (control) and E2-treated groups were determined using Dunnett's one-way analysis of variance or Bonfferoni's multiple comparison test to compare selected pairs of columns. Differences were considered statistically significant at *p ≤ 0.05, or **p ≤ 0.01. Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for graphing and statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Quantitative real-time PCR: time course studies

To investigate in detail UGT1A10 regulation by E2, real-time PCR was performed on cDNA samples from the MCF-7 cell line treated with E2 (0.1 nM) for 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h (Figure 1). E2-mediated increases in UGT1A10 mRNA were observed as early as 4 h. Maximal induction of UGT1A10 mRNA levels was observed at 8 h, with mRNA levels remaining elevated after 48 h of treatment. A treatment time of 8 h was used in subsequent studies because this time point yields maximal stimulation of UGT1A10.

Figure 1. Time dependence of UGT1A10 mRNA expression in MCF-7 ER-positive breast cancer cells treated with 0.1 nM E2.

MCF-7 cells were treated with E2 (0.1 nM) for 2, 4, 8, 24, or 48 h. UGT1A10 mRNA expression was analyzed by QRT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the ratio of mRNA in treated cells to that in control cells treated with vehicle (fold change from control). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Quantitative real-time PCR: dose-response studies

Dose-response studies were performed with cells of the MCF-7 (ER-positive) and MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative) breast cancer cell lines treated for 8 h with concentrations of E2 ranging from 1 pM to 10 nM (Figure 2A and 2B). E2 induction, followed by suppression, of UGT1A10 mRNA levels occurred in a dose-dependent manner in MCF-7 cells. Induction was observed at concentrations as low as 10 nM, with 0.1 nM E2 giving maximal stimulation, followed by a steady decrease to near control levels at 10 nM. E2 did not stimulate MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative) cells, suggesting that the effect of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA in MCF-7 (ER-positive) cells might be mediated through the ER. An E2 concentration of 0.1 nM was frequently used in subsequent studies because, of the concentrations studied, this concentration yielded maximal stimulation of UGT1A10 mRNA.

Effect of E2 on UGT2B15 and UGT2B7 mRNA expression

To assess the mRNA expression of UGT2B15 and UGT2B7, dose-response studies were performed with MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines treated for 8 h with concentrations of E2 ranging from 1 pM to 10 nM (Figure 3A and 3B). Induction of UGT2B15 mRNA was observed at concentrations as low as 1 pM E2, with 10 nM E2 producing maximal observed stimulation of UGT2B15, which is in agreement with previous studies by Harrington et al. [29]. By contrast, E2 had no effect on UGT2B7 mRNA expression. These findings suggest that the regulation of UGT genes by E2 may be isoform-specific.

Effect of the ER agonists, PPT and genistein, and the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 on UGT1A10 mRNA: dose-response studies

For dose-response studies, MCF-7 ER-positive cell lines were treated for 8 h with the ERα-selective agonist PPT at concentrations ranging from 5−200 nM. PPT is an ERα-selective ligand that has been shown to have over 400-fold selectivity for ERα over ERβ [30]. PPT stimulation of UGT1A10 mRNA levels occurred in a dose-dependent manner in MCF-7 cell lines (Figure 4A). Induction was observed at concentrations as low as 5 nM, with 200 nM PPT giving maximal stimulation of the concentrations studied. The phytoestrogen genistein also stimulated UGT1A10 mRNA levels in a dose-dependent manner in MCF-7 cell lines (Figure 4B). Induction of UGT1A10 mRNA levels was observed at concentrations as low as 0.25 nM, with 2 nM genistein giving maximal stimulation of the concentrations studied. ICI 182,780 (10 nM to 1.0 μM) had no affect on UGT1A10 mRNA expression (Figure 4C).

Effects of ICI 182,780, CHX, and the transcriptional inhibitor, actinomycin-D, on UGT1A10 mRNA

To determine if the effects of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA induction might be mediated through ER, MCF-7 cell lines were exposed to E2 (0.1 nM) and the antiestrogen, ICI 182,780 (1 μM), which competes with E2 for binding at ERα. MCF-7 cell lines were treated with E2 (0.1 nM) for 8 h with or without a 2 h pretreatment with ICI 182,780 (1 μM; Figure 5A). Co-treatment of MCF-7 cell lines with ICI 182,780 and E2 completely abolished the expression of UGT1A10 mRNA levels produced by E2 treatment alone. This suggests that the stimulation of UGT1A10 gene transcription by E2 might be mediated through ER.

To assure that UGT1A10 mRNA down-regulation was not due to increased instability of mRNA or protein in the presence of estrogens, actinomycin-D, a transcriptional inhibitor, was used to prevent de novo RNA synthesis and CHX, a translational inhibitor, was used to prevent de novo protein synthesis (Figure 5B). Preincubation of MCF-7 cells with actinomycin-D (1 ug/mL) abolished the induction of UGT1A10 mRNA by E2 completely, whereas CHX treatment did not significantly affect induction UGT1A10 by E2.

Finally, to further ensure that UGT1A10 mRNA down-regulation was not due to increased instability of mRNA in the presence of estrogens, MCF-7 cell lines were treated for various times with either ethanol (control), E2 (0.1 nM), PPT (200 nM), or genistein (2 uM) in the presence of actinomycin-D (1 μg/ml) (Figure 6). The half-life of UGT1A10 mRNA was calculated by plotting the percentage of RNA remaining in actinomycin-D-treated cell lines versus time and fitting that plot using GraphPad Prism 4 software. The half-lives of mRNA decay of ethanol, E2, PPT, and genistein were 2.318, 2.867, 2.095, 2.834 h, respectively. Thus, treatment with estrogens did not affect the stability of UGT1A10 mRNA, indicating that the suppression of UGT1A10 mRNA is, not at the level of translation but, most likely at the transcriptional level.

Effect of E2 on UGT1A protein levels and enzymatic activity

To investigate whether induction of UGT1A10 mRNA results in an increase in UGT1A10 protein levels, Western blot analysis was performed using microsomes isolated from MCF-7 cells treated with ethanol vehicle (control), or E2 at 0.1 nM, or 10 nM for 8 h (Figure 7). Since a specific UGT1A10 antibody is not available, the Western blot experiments were carried out using an antibody designed to identify the identical C-terminal end of all UGTs from the 1A family. Unpublished data indicates that of the UGT1A isoforms, only 1A10 mRNA (and very low levels of UGT1A1). Because of this any change in UGT1A expression can be interpreted as the result of changes in UGT1A10. As shown in figure 7A, UGT1A protein levels were very low in control cells and in cells treated with 10 nM E2. However, treatment of MCF-7 cells with 0.1 nM E2 increased UGT1A protein levels above those of both control and 10 nM E2 treated cells.

Figure 7. Effect of E2 treatment of MCF-7 cells on UGT1A protein levels and activity.

(A) Western blot analysis of UGT1A protein. MCF-7 cells treated with vehicle (control), 0.1 nM E2, and 10 nM E2. The blot was probed with an anti-UGT1A polypeptide antibody that detects all of the UGT1A isoforms. Calnexin protein levels were also monitored to assess protein loading. (B) UGT enzymatic activity toward E2. MCF-7 cells were treated with ethanol (control), 0.1 nM E2, and 10 nM E2. Reactions were done as described in the text and the rates of E2 glucuronide formation were detrmined by scintillation counting following TLC and autoradiography. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three experiments performed in duplicate. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, are considered statistically significantly compared to control.

The increase in UGT1A protein observed with E2 treatment was also associated with an increase in glucuronidation activity toward E2. As shown in Figure 7B, microsomes from cells treated with 0.1 nM E2 for 8 hr glucuronidated E2 at a level 5 times higher than that of control cells and cells treated with 10 nM E2.

DISCUSSION

Estrogens play critical roles in the regulation and development of the breast. The action of estrogens in the breast is dependent upon many factors including the ER and the activity of estrogenic enzymes involved in the biosynthesis and metabolism of estrogens in the breast [31]. It is recognized that a variety of endogenous and exogenous estrogens are eliminated from the body as glucuronide conjugates formed by UGT enzymes [23,32]. However, recent findings suggest that estrogens may regulate UGT expression [29].

Recent studies by Harrington et al. [29] demonstrated that UGT2B15, which is involved in the glucuronidation of estrogens and androgens, and is highly expressed in several steroid target tissues, is a novel estrogen-regulated target gene in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cell lines, including MCF-7 cells [29]. In those studies, estrogens, including PPT and genistein, and androgens stimulated the expression of UGT2B15 in a dose- and time-dependent manner in MCF-7 cells, but did not stimulate UGT2B7 expression [29]. In addition, co-treatment of MCF-7 cells with the antiestrogen, ICI 182,780, and E2 blocked the expression of UGT2B15. Collectively, those findings suggest that up-regulation of UGT2B15 expression by estrogens was likely mediated through ER.

Recently, our laboratory and others have identified UGT1A10 as being major UGT isoform that conjugates native estrogens and/or their 2- and 4-hydroxylated metabolites [23,32]. UGT1A10 is also known to conjugate bioflavonoids, phenols, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are carcinogenic [25] and is highly expressed in several tissues of the gastrointestinal tract including biliary tract, colon, stomach, and duodenum [25]. Recent studies from our laboratory (unpublished data) have shown that UGT1A10 is also expressed and functional in human breast tissues. The identification of UGT1A10 in conjugating estrogens and the expression of UGT1A10 in human breast tissues are novel findings. Considering the important role that estrogens play in the development of breast cancer, the present study was aimed at analyzing the effect of estrogens on the expression of several UGT enzymes in the classical breast cancer cell models MCF-7 (ER-positive) and MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative) breast cancer cell lines.

To investigate whether UGT1A10 might be an estrogen-regulated gene in MCF-7 ER-positive breast cancer cells, the effects of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA expression were characterized. The results showed that exposure of MCF-7 cells to E2 up-regulated, and then down-regulated, UGT1A10 mRNA expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Moreover, other estrogens, PPT and genistein, also stimulated the expression of UGT1A10 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, UGT2B15 mRNA expression was stimulated by E2 in a dose-dependent manner, but did not stimulate UGT2B7 mRNA levels, which is in agreement with the findings from Harrington et al [29]. These findings suggest that the regulation of UGT genes by E2 may be isoform-specific.

Treatment of MDA-MB-231 ER-negative cells with E2 did not stimulate UGT1A10 mRNA expression, suggesting that this response may be at the transcriptional level. Treatment of MCF-7 cells with E2 and the antiestrogen, ICI 182,780, completely abolished the effects of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA expression. Co-treatment of MCF-7 cells with the transcriptional inhibitor, actinomycin-D, completely abolished the induction of UGT1A10 mRNA by E2. However, CHX treatment did not significantly influence this induction. These results indicate that Estradiol induced the expression of the UGT1A10 gene at the transcriptional level without requiring de novo protein synthesis. This supports the hypothesis that UGT1A10 mRNA expression might in fact be a primary transcriptional response mediated through ER [29]. Furthermore, the increased expression of UGT1A10 mRNA after E2 stimulation in comparison to UGT1A protein levels further support the hypothesis that the effect of E2 on UGT1A10 mRNA is transcriptional.

The molecular mechanisms by which estrogens regulate UGT1A10 mRNA expression and activity needs to be fully elucidated. However, previous studies involving the up-regulation of UGT2B15 in ER-positive breast cancer cells (MCF-7, BT474, and ZR-75) by estrogens and androgens were suggested to occur at the transcriptional level and were mediated through ER [29]. Furthermore, the up-regulation of UGT2B15 by estrogen and androgens in estrogen responsive breast cancer cells were proposed to represent a novel feedback mechanism on estrogen signaling or a means of cross-talk between the androgen and estrogen signaling pathways; thereby providing a means of controlling local estrogen and androgen levels for their receptors [29].

Supporting studies have established that androgens can also reduce the expression and activity of androgen-conjugating UGT enzymes, i.e. UGT2B15 and UGT2B17, in prostate carcinoma cells [33]. The negative regulatory effects were closely associated to increased growth and proliferation in LNCaP prostate carcinoma cells, which express both androgen and estrogen receptors. In this study, it was postulated that UGT2B15 and UGT2B17 down-regulation was mediated by androgen-activated androgen receptor (AR).

Estrogen receptors can also affect gene expression by binding to silencer elements in the promoter regions of estrogen-target genes. For example, a study by Yang et al. [34] demonstrated that ERα could bind to a silencer element in the aromatase gene, consequently down-regulating aromatase promoter activity and expression in human breast tissues. Recruitment of ER corepressor proteins to EREs have also been proposed to repress the expression of estrogen target genes [35]. Other mechanisms of gene silencing by ER corepressors include competition with coactivators, interference with DNA binding and ERα homodimerization, alteration of ERα stability, sequestration of ERα in the cytoplasm, and effects on RNA processing [35].

The promoter sequence of the UGT1A10 gene was examined for putative ERE sequences using computer software, GeneDoc (www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc), to search for known DNA-binding protein recognition sites. As yet, there have been no published analyses of the promoter region of any UGT gene that have revealed any indication of an ERE; however, we were able to identify two putative ERE half-sites were observed in the 5'-flanking region of the UGT1A10 gene (data not shown). In support of these novel findings, other studies have shown that ERα has a higher affinity for ERE half-sites than the full-length consensus ERE sequence [36,37]. Thus, the UGT1A10 promoter could be under the control of ER and therefore ER could have a significant moderating effect on the transcriptional regulation of UGT1A10.

The observation that UGT1A10 is up- and then down-regulated in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line by increasing concentrations of E2 might have implications in the pathogenesis of breast cancer. Recent supporting data from our laboratory (unpublished data) have identified expression of UGT1A10 mRNA in the breast for the first time. These studies demonstrate that UGT1A10 mRNA, protein, and enzymatic activity toward E2 and the genotoxic, 4-OH-E1, were significantly down-regulated in breast carcinomas compared to histologically normal breast tissues. We hypothesized that decreased glucuronidation of E2 might be due to accumulation of E2 in breast cells and tissues, resulting in enhanced E2-mediated cell signaling via estrogen receptors, and increased E2 concentrations might be required to help maintain the excess levels of E2 required to stimulate the growth and progression of the tumor.

In summary, an important finding from the present study is that UGT1A10, which is actively involved in the conjugation of estrogens, is a novel estrogen regulated gene. In our breast cell culture systems the mRNA expression of UGT1A10 is induced in response to E2. However, perhaps one of the more interesting and novel findings revealed by this study is that this response is not directly correlated with the concentration of E2. Once maximal induction is reached at 0.1 nM, further increases in E2 concentration reverse this induction. Once the concentration reaches 10 nM UGT1A10 mRNA expression has almost returned to the basal level of expression. It will be important to correlate this in vitro data to in vivo levels of E2 in human breast tissue.

These findings suggest that UGT1A10, as well as UGT2B15, might play a significant role in controlling the local concentrations of estrogens in estrogen-responsive breast cancer cells. Studies to define the molecular mechanism of UGT1A10 and UGT2B15 regulation by E2 through the ER are under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grant support: This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health grant DK60109 and GM075893 and Tobacco Settlement Funds to A. Radominska-Pandya. A. Starlard-Davenport is the recipient of a minority supplement award from the National Institute of Health.

Abbreviations

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Porter JC. Proceedings: Hormonal regulation of breast development and activity. J Invest Dermatol. 1974;63:85–92. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12678099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keen JC, Davidson NE. The biology of breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:825–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacGregor JI, Jordan VC. Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:151–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuchiya M, Nakao H, Katoh T, Sasaki H, Hiroshima M, Tanaka T, Matsunaga T, Hanaoka T, Tsugane S, Ikenoue T. Association between endometriosis and genetic polymorphisms of the estradiol-synthesizing enzyme genes HSD17B1 and CYP19. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:974–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McEwen BS, Alves SE. Estrogen actions in the central nervous system. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:279–307. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with co-activators and co-repressors. Steroids. 2000;65:227–51. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. From ligand to response: generating diversity in nuclear receptor coregulator function. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74:351–6. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halachmi S, Marden E, Martin G, MacKay H, Abbondanza C, Brown M. Estrogen receptor-associated proteins: possible mediators of hormone-induced transcription. Science. 1994;264:1455–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8197458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radominska-Pandya A, Czernik PJ, Little JM, Jude AR, Tephly TR, Carter CA. Identification of the recombinant UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 in nuclear envelopes.. DMW/ISSX Meeting 2000; St. Andrews, Fife, Scotland. June 11−16, 2000.2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutton GJ. Glucuronidation of Drugs and Other Compounds. CRC Press Inc.; Boca Raton, Fl.: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bock KW, Lilienblum W, Fischer G, Schirmer G, Bock-Henning BS. The role of conjugation reactions in detoxication. Arch Toxicol. 1987;60:22–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00296941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffman BL, King CD, Rios GR, Tephly TR. The glucuronidation of opioids, other xenobiotics, and androgens by human UGT2B7Y(268) and UGT2B7H(268). Drug Met. and Disp. 1998;26:73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Formelli F, Barua AB, Olson JA. Bioactivities of N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide and retinoyl beta-glucuronide. FASEB Journal. 1996;10:1014–24. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vore M, Montgomery C, Meyers M. Steroid D-ring glucuronides: characterization of a new class of cholestatic agents. Drug Metab Rev. 1983;14:1005–19. doi: 10.3109/03602538308991419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oelberg DG, Chari MV, Little JM, Adcock EW, Lester R. Lithocholate glucuronide is a cholestatic agent. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1507–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI111356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroemer HK, Klotz U. Glucuronidation of drugs. A re-evaluation of the pharmacological significance of the conjugates and modulating factors. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;23:292–310. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199223040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackenzie PI, Owens IS, Burchell B, Bock KW, Bairoch A, Belanger A, Fournel-Gigleux S, Green M, Hum DW, Iyanagi T, Lancet D, Louisot P, Magdalou J, Chowdhury JR, Ritter JK, Schachter H, Tephly TR, Tipton KF, Nebert DW. The UDP glycosyltransferase gene superfamily: recommended nomenclature update based on evolutionary divergence. Pharmacogenetics. 1997;7:255–69. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong QH, Cho JW, Huang T, Potter C, Gholami N, Basu NK, Kubota S, Carvalho S, Pennington MW, Owens IS, Popescu NC. Thirteen UDPglucuronosyltransferase genes are encoded at the human UGT1 gene complex locus. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:357–68. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tukey RH, Strassburg CP. Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases: metabolism, expression, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:581–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackenzie PI, Miners JO, McKinnon RA. Polymorphisms in UDP glucuronosyltransferase genes: functional consequences and clinical relevance. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38:889–92. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2000.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King CD, Rios GR, Green MD, Tephly TR. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Curr Drug Metab. 2000;1:143–61. doi: 10.2174/1389200003339171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radominska-Pandya A, Pokrovskaya ID, Xu J, Little JM, Jude AR, Kurten RC, Czernik PJ. Nuclear UDP-glucuronosyltransferases: identification of UGT2B7 and UGT1A6 in human liver nuclear membranes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;399:37–48. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starlard-Davenport A, Xiong Y, Bratton S, Gallus-Zawada A, Finel M, Radominska-Pandya A. Phenylalanine(90) and phenylalanine(93) are crucial amino acids within the estrogen binding site of the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A10. Steroids. 2007;72:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basu NK, Kubota S, Meselhy MR, Ciotti M, Chowdhury B, Hartori M, Owens IS. Gastrointestinally distributed UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A10, which metabolizes estrogens and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, depends upon phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28320–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewinsky RH, Smith PA, Mackenzie PI. Glucuronidation of bioflavonoids by human UGT1A10: structure-function relationships. Xenobiotica. 2005;35:117–29. doi: 10.1080/00498250400028189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strassburg CP, Manns MP, Tukey RH. Expression of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A locus in human colon. Identification and characterization of the novel extrahepatic UGT1A8. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8719–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul P, Lutz TM, Osborn C, Kyosseva S, Elbein AD, Towbin H, Radominska A, Drake RR. Synthesis and characterization of a new class of inhibitors of membrane-associated UDP-glycosyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12933–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little JM, Williams L, Xu J, Radominska-Pandya A. Glucuronidation of the dietary fatty acids, phytanic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, by human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:531–3. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrington WR, Sengupta S, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen regulation of the glucuronidation enzyme UGT2B15 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3843–50. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, Nishiguchi G, Carlson K, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Pyrazole ligands: structure-affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-alpha-selective agonists. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4934–47. doi: 10.1021/jm000170m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raftogianis R, Creveling C, Weinshilboum R, Weisz J. Estrogen metabolism by conjugation. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000:113–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basu NK, Ciotti M, Hwang MS, Kole L, Mitra PS, Cho JW, Owens IS. Differential and special properties of the major human UGT1-encoded gastrointestinal UDP-glucuronosyltransferases enhance potential to control chemical uptake. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1429–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guillemette C, Levesque E, Beaulieu M, Turgeon D, Hum DW, Belanger A. Differential regulation of two uridine diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases, UGT2B15 and UGT2B17, in human prostate LNCaP cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2998–3005. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.7.5226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Yu B, Zhou D, Chen S. Regulation of aromatase promoter activity in human breast tissue by nuclear receptors. Oncogene. 2002;21:2854–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobrzycka KM, Townson SM, Jiang S, Oesterreich S. Estrogen receptor corepressors -- a role in human breast cancer? Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:517–36. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson I, Gorski J. Estrogen receptor alpha interaction with estrogen response element half-sites from the rat prolactin gene. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3842–7. doi: 10.1021/bi9924516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das D, Peterson RC, Scovell WM. High mobility group B proteins facilitate strong estrogen receptor binding to classical and half-site estrogen response elements and relax binding selectivity. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2616–32. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]