Abstract

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (aRMS), an aggressive skeletal muscle cancer, carries a unique t(2;13) chromosomal translocation resulting in the formation of a chimeric transcription factor PAX3-FKHR. This fusion protein contains the intact DNA-binding domains (PD: paired box binding domain; HD: paired-type homeodomain) of Pax3 fused to the activation domain of FKHR. Cells expressing Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR show vastly different gene expression patterns, despite that they share the same DNA-binding domains. We present evidence of a gain of function mechanism that allows the fusion protein to recognize and transcriptionally activate response elements containing a PD-specific binding site. This DNA recognition specificity is in contrast to the requirement for Pax3-specific target sequences that must contain a composite of PD-and HD-binding sites. Domain swapping studies suggest that an increased structural flexibility could account for the relaxed DNA targeting specificity in PAX3-FKHR. Here, we identify myogenin gene as a direct target of PD-dependent PAX3-FKHR activation pathway in vitro and in vivo. We demonstrate that PAX3-FKHR could induce myogenin expression in undifferentiated myoblasts by a MyoD independent pathway, and that PAX3-FKHR is directly involved in myogenin expression in aRMS cells.

Keywords: oncogene, rhabdomyosarcoma, transcription, chromosomal translocation

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma a malignant skeletal muscle tumor occurs mainly in children and adolescents. The alveolar subtype (aRMS) is the most aggressive with the poorest prognostic outcome. Over 85% of patients with aRMS carries a unique chromosomal translocation that produces a fusion protein known as PAX3-FKHR (Turc-Carel et al., 1986; Douglass et al., 1987; Wang-Wuu et al., 1988). The chimeric transcription factor PAX3-FKHR contains intact N-terminal PAX3 DNA-binding domains (DBDs; the paired-box domain PD and the paired-type homeodomain HD) fused to the C-terminal region of FKHR containing truncated winged helix DBD and the activation domain (AD) of FKHR separated by a 330-amino acid linker region (Barr et al., 1993, 1997; Shapiro et al., 1993). Although the etiology of aRMS remains unknown, the persistent expression of these fusion proteins in the vast majority of the aRMS tumors strongly suggests active participation in tumor development.

A series of in vitro and in vivo experiments link PAX3-FKHR to aRMS tumorigenesis. For example, ectopic expression of PAX3-FKHR transforms primary and immortalized fibroblast (Scheidler et al., 1996; Lam et al., 1999; Cao and Wang, 2000) and myoblast cells (Zhang and Wang, unpublished data). Myoblast cells expressing PAX3-FKHR fail to undergo terminal differentiation into myotubes (Epstein et al., 1995). When introduced into embryonal RMS cells, PAX3-FKHR induces morphological change and enhances proliferation and invasion of these already transformed cells (Anderson et al., 2001). Targeted knock down of PAX3-FKHR expression in aRMS cells reduces their growth rate and leads to apoptosis (Bernasconi et al., 1996). Recently, the first aRMS mouse model was developed, which conditionally activates PAX3-FKHR expression in developing skeletal muscle (Keller et al., 2004b). The tumor incidence in these mice increases with introduction of additional genetic defects (e.g., deletion of Ink4A/ARF locus, p53 gene mutation, Keller et al., 2004a). Together, these studies suggest that PAX3-FKHR plays a primary role in muscle cell transformation and may function at multiple stages of aRMS development.

Despite the functional evidence, the molecular mechanisms underlying the PAX3-FKHR-mediated pathology remain elusive. Initial investigation on the transactivation specificity of PAX3-FKHR has revealed that fusion protein retains wild-type Pax3-DNA-binding specificity, but with greater transcriptional activation because the FKHR AD is more potent than the Pax3 AD (Fredericks et al., 1995). Pax3 protein binds with high affinity in vitro to a complex DNA response element that contains a PD recognition site (GTT C/A C/T) adjacent to a HD recognition site (ATTA) (Goulding et al., 1991). The in vitro electrophoretic mobility shift assay and in vivo transfection experiments reveal that both PD and HD are required for Pax3 function, suggesting a synergistic interaction between the two DBDs (i.e., PD/HD-dependent mechanism; Chalepakis et al., 1994b; Chalepakis and Gruss, 1995). It is postulated that PAX3-FKHR, being a more potent transcription activator, must elicit its oncogenic effect by abnormally regulating Pax3-dependent genes. However, this mechanism cannot explain why high level of Pax3 cannot recapitulate the oncogenic functions of PAX3-FKHR. These apparent conflicts lead to speculation that PAX3-FKHR may activate additional target genes different from those activated by Pax3, hence enabling the fusion protein to disrupt cellular activities not normally regulated by Pax3. This notion is consistent with reports that describe many differences in the gene expression profiles between Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR expressing cells (Khan et al., 1999; Begum et al., 2005; De Pitta et al., 2006). The first concrete evidence to support this hypothesis came from our study that shows PAX3-FKHR activates the platelet-derived growth factor-alpha receptor (PDGFαR) gene in a HD-dependent, PD-independent mechanism (Epstein et al., 1998). The HD-dependent transcription mechanism is crucial for the transforming activities of PAX3-FKHR (Lam et al., 1999). These studies highlight the importance of gain-of-function mechanism in PAX3-FKHR pathogenesis.

In this work, we show that PAX3-FKHR activates the myogenin gene through a PD-dependent, HD-independent activity. This selective activation of PD activity depended on a cooperative communication between Pax3 and FKHR portions of the fusion protein. Despite that aRMS cells are unable to properly exit cell cycle, a required step for muscle cell differentiation, they express intense levels of myogenin mRNA and protein (Dias et al., 2000; Folpe, 2002; Michelagnoli et al., 2003; Hostein et al., 2004). It is not clear how aRMS cells accumulate such high myogenin levels since myogenin is a myogenic regulator specifically expressed in differentiated muscles. Data presented here provides a mechanistic basis that directly links PAX3-FKHR as a transcriptional activator responsible for the aberrant myogenin gene expression in aRMS.

Results

PAX3-FKHR is an upstream regulator of myogenin gene in muscle cells

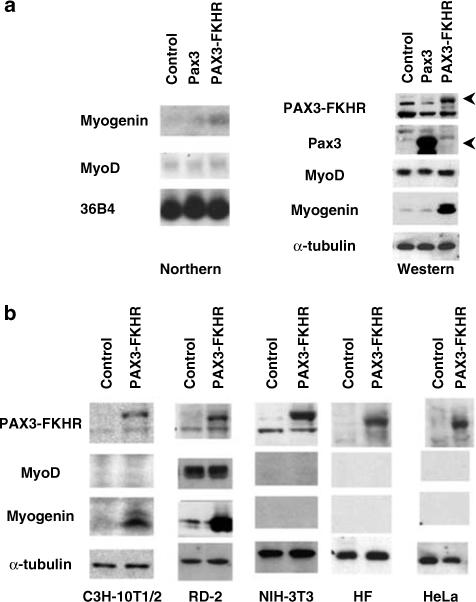

Recent immunohistochemical studies have revealed that myogenin, a myogenic differentiation marker, is selectively expressed at high levels in aRMS tumors, making it a reliable diagnostic marker. However, the underlying mechanism for myogenin gene regulation in aRMS is not known. We examined if PAX3-FKHR induced myogenin expression in undifferentiated C2 myoblast cells using retroviral infection. As controls, C2 cells were infected with the empty retrovirus expression vector or with vector encoding Pax3. At 72 h post-infection, myogenin protein and mRNA content was increased in C2 cells expressing PAX3-FKHR but was not changed in control and Pax3 expressing cells (Figure 1a). Importantly, expression of MyoD, the normal activator of myogenin during muscle differentiation, was not affected by PAX3-FKHR. PAX3-FKHR-induced myogenin expression in embryonal RMS and mesenchymal cells, but not in fibroblast or epithelial cells (Figure 1b). Thus, PAX3-FKHR induction of myogenin is cell-type specific and MyoD-independent.

Figure 1.

Induction of myogenin gene in C2 cells by PAX3-FKHR. (a) Exponentially growing C2 cells were infected with retrovirus containing empty vector (control) or vector expressing Pax3 or PAX3-FKHR. Total RNA(20 μg) or 50 μg of RIPA extracted proteins were analysed for myogenin mRNA (Northern) and protein (Western) content. Samples were normalized to 36B4 (Northern) or α tubulin (Western). (b) Western blot analysis of the cell type-dependent myogenin induction by PAX3-FKHR.

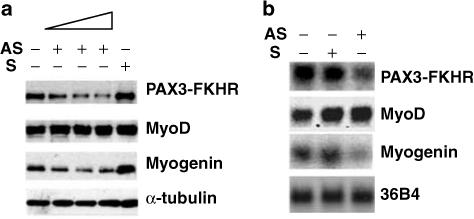

We next investigated the role of PAX3-FKHR in myogenin expression in aRMS cells using antisense oligo (AS-ODN) to reduce endogenous PAX3-FKHR expression in RH30 cells; this AS-ODN was shown to effectively knockdown PAX3-FKHR expression (Bernasconi et al., 1996). As prolonged reduction of the fusion protein in aRMS cells induces apoptosis, we studied cells 48 h after transfection when cell death was consistently less than 15% by trypan blue. Control cells were transfected with S-ODN or transfection reagent alone. AS-ODN treatment significantly reduced myogenin expression compared to control cells (Figure 2). MyoD was unchanged by the same treatment. These data indicate that PAX3-FKHR induction of myogenin occurs independently of MyoD.

Figure 2.

Myogenin expression in RH30 cells is reduced by down regulation of PAX3-FKHR. RH30 cells were MOCK transfected (lane 1) or transfected with PAX3-FKHR AS-ODN (lane 2: 100 nM, lane 3: 250 nM, lane 4: 500 nM), or S-ODN (lane 5: 500 nM). At 48 h post-transfection, cells were analysed for MyoD and myogenin content by Western (a) and Northern blots (b).

PAX3-FKHR regulates myogenin transcription through a novel regulatory mechanism

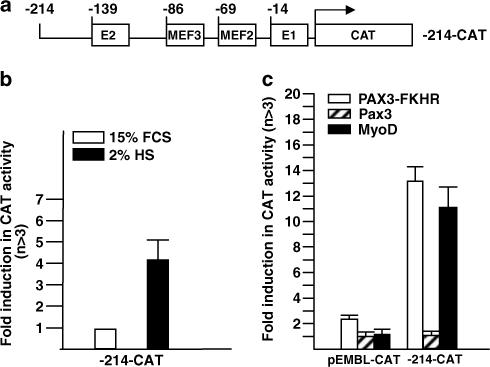

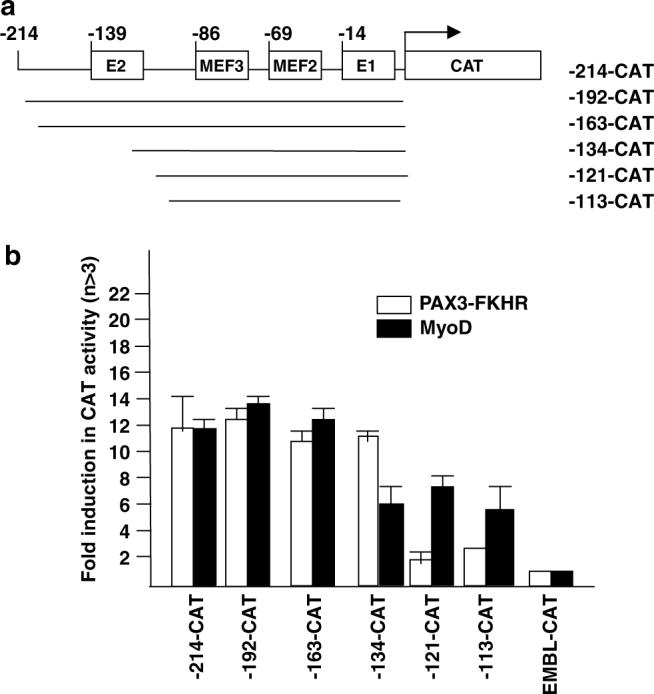

As PAX3-FKHR is a potent transcription factor, its effect on myogenin is most likely due to direct transcriptional activation. We tested this by determining whether PAX3-FKHR could directly transactivate the 214-bp myogenin promoter linked to a CAT reporter gene (Figure 3a). As previously reported (Buchberger et al., 1994), this promoter was activated by differentiation medium or by ectopic expression of MyoD in undifferentiated C2 myoblasts (Figure 3b–c). PAX3-FKHR, but not Pax3, transactivated myogenin promoter as efficiently as MyoD (Figure 3c), supporting myogenin as a direct target for PAX3-FKHR transcriptional activation.

Figure 3.

Transactivation of the myogenin promoter by PAX3-FKHR. (a) Schematic illustration of the −214 myogenin promoter CAT reporter construct, showing positions of the four known cis-regulatory elements. (b) Differentiation-dependent activation of −214-CAT reporter construct in C2 cells. Ten microgram of −214-CAT or promoterless CAT construct (EMBL-CAT) was transiently transfected into duplicate plates of undifferentiated C2 cells. Afterwards, one plate was maintained in growth medium (15% FCS) and the other plate in differentiation medium (2% HS) for 48 h before harvest. Fold activity was calculated as the level of CAT activity from the −214-CAT construct over that from the promoterless EMBL-CAT construct, which was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. (c) Transactivation of the myogenin promoter by PAX3-FKHR, Pax3, or MyoD in C2 cells. −214-CAT was co-transfected with empty expression vector (pcDNA3) or vector containing Pax3, PAX3-FKHR, or MyoD (5 μg). Fold induction in CAT activity was calculated as the level of CAT activity in cells expressing exogenous transcription factors over that from empty vector pcDNA3. The values shown in Figures 3b–c represented means and standard deviations for a minimum of three independent experiments. The standard deviation is defined as the root mean square deviation of the n-1 determinations.

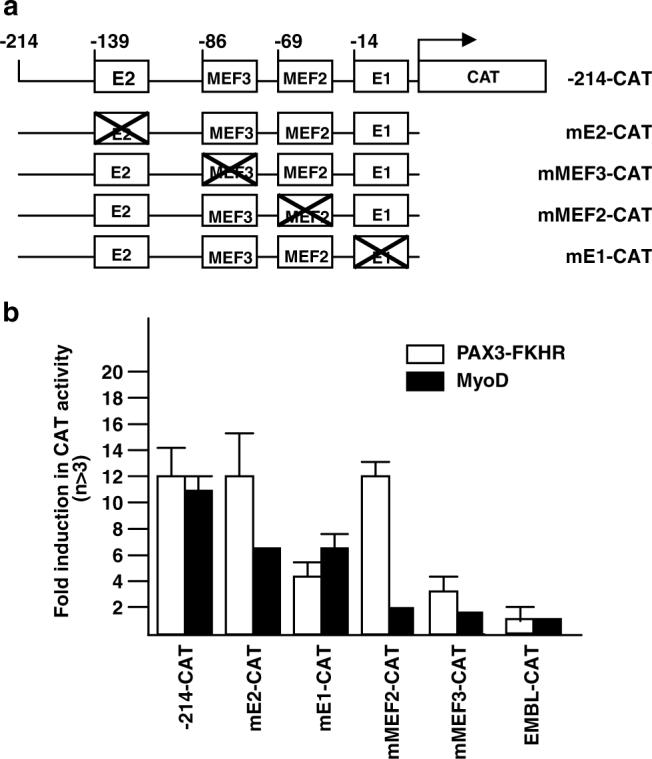

Although MyoD is expressed in undifferentiated myoblast cells, it is found in inactive complexes with myogenic antagonists such as Id and Twist (Jen et al., 1992; Spicer et al., 1996). While PAX3-FKHR did not alter MyoD expression level in C2 cells, we could not rule out the possibility that PAX3-FKHR might alter the activity of existing MyoD. We turned to mutational analysis to address this issue. The 214-bp myogenin promoter contains several transcription factor-binding sites (Figure 3a) critical for MyoD activation of myogenin during myogenesis (Cheng et al., 1992, 1993). These sites include two MyoD binding E-box elements (distal E2 and proximal E1, Yee and Rigby, 1993; Malik et al., 1995) flanking a MEF2-binding element (MEF2, Buchberger et al., 1994) and a Six binding element (MEF3, Spitz et al., 1998). Neither MEF2 nor Six can drive myogenin expression, but their cooperation with MyoD is required for full myogenin activation during differentiation. To rule out a direct role of MyoD in the PAX3-FKHR induction of myogenin, we asked whether PAX3-FKHR could still transactivate the myogenin promoter when each of these four binding sites was mutated (Figure 4a). As previously reported, mutation of any of the four sites affected MyoD transactivation of myogenin. By contrast, PAX3-FKHR transactivation of myogenin was only affected by E1 or MEF3 mutation (Figure 4b). Most strikingly, the MEF2 mutation that abolished MyoD transactivation had no effect on PAX3-FKHR transactivation. The differential response of these mutational constructs towards transactivation by PAX3-FKHR versus MyoD confirms the action of PAX3-FKHR on myogenin involves an alternative mechanism independent of MyoD.

Figure 4.

Effect of E1, E2, MEF2 and MEF3 mutations on PAX3-FKHR and MyoD- transactivation of the myogenin promoter. (a) Schematic illustration −214-CAT promoter mutants. (b) Transactivation of wild type and mutant myogenin promoter-CAT constructs (10 μg) by pcDNA3 or vector containing Pax3, PAX3-FKHR or MyoD (5 μg) in C2 cells. Fold-induction was as described in Figure 3c.

PAX3-FKHR regulates myogenin gene transcription through a direct interaction with a gPFRE site

The above mutational analysis shows the requirements for PAX3-FKHR transactivation of the myogenin promoter differs from those for MyoD, implying the involvement of additional regulatory elements beyond the four elements indicated in Figure 3. We used 5′ deletion constructs of −214CAT to identify the region within myogenin promoter involved in PAX3-FKHR transactivation (Figure 5a). PAX3-FKHR or MyoD transactivation of the myogenin promoter was unchanged by deletion of the −214 to −163 bp region (Figure 5b); however, deletion of the region from −163 to −134 significantly reduced transactivation by MyoD but not by PAX3-FKHR. This region contains the E2 element that when mutated, is known to reduce the level, but not specificity of MyoD transactivation of myogenin. Further deletion of the region from −134 to −121 nearly abolished transactivation by PAX3-FKHR, but to not by MyoD. This suggests that the −134 to −121 bp region of the myogenin promoter contains a critical response element required for PAX3-FKHR action. We refer to this region as the myogenin-specific PAX3-FKHR regulatory element, gPFRE.

Figure 5.

Localization of PAX3-FKHR response element (gPFRE) within the myogenin promoter. (a) Schematic illustration of 5′-deletion constructs of the myogenin promoter. (b) Transient transfection and CAT assays were performed as described in Figure 3c.

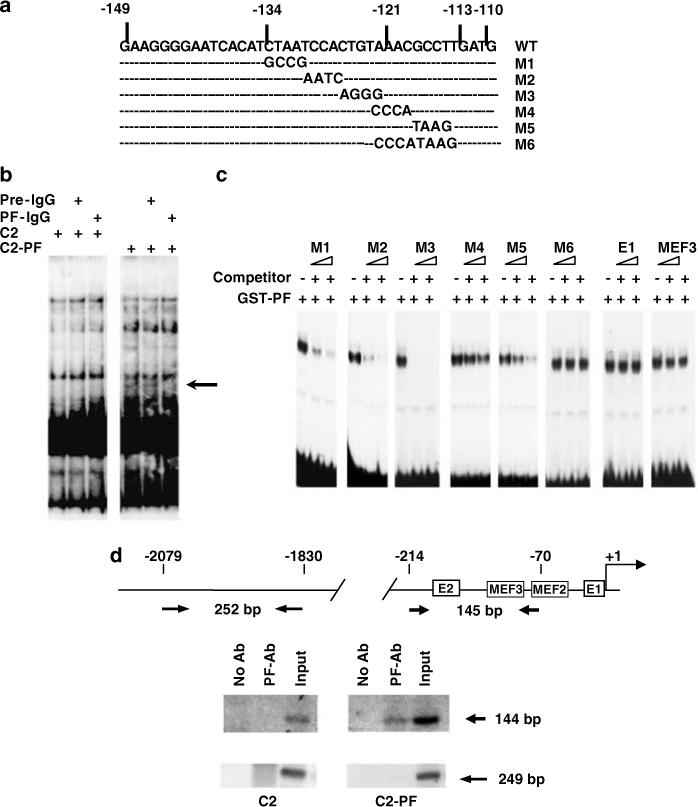

Next, we investigated whether PAX3-FKHR could sequence-specifically bind to wt-gPFRE (Figure 6a). First, we compared binding to wt-gPFRE by nuclear extracts from C2 and PAX3-FKHR-expressing C2 (C2-PF) cells. The extracts from C2-PF but not C2 cells formed a specific DNA-protein complex (arrow, Figure 6b). Inclusion of an antibody specific for PAX3-FKHR disrupted the complex. Second, a competition study verified the sequence-specificity of binding and identified the sequence required for binding of PAX3-FKHR to gPFRE. In this study, we evaluated the ability of various mutant oligos to compete for binding of purified GST-PAX3-FKHR to the wt-gPFRE probe. Analysis of the six mutations to gPFRE shows that the M1, M2 and M3 mutations did not affect binding since they readily competed with gPFRE for binding (Figure 6c). However, the M4, M5 and M6 mutations did reduce (and for M6 abolish) competition for binding to gPFRE. E1 or MEF3 oligos did not compete with gPFRE for binding even though both sites contribute to PAX3-FKHR transactivation. Neither MyoD nor Pax3 was able to bind gPFRE (data not shown). Third, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis showed that PAX3-FKHR was bound to the endogenous myogenin promoter in vivo in C2-PF cells (Figure 6d). This in vivo interaction was also observed in RH30 cells but not NIH3T3 cells (data not shown).

Figure 6.

PAX3-FKHR binding to gPFRE from the myogenin promoter. (a) DNA sequence of the wild-type (WT) and mutant (M1–M6) gPFRE. (b) EMSA analysis of C2 and C2-PF nuclear extract binding to WT gPFRE DNA probe. Purified IgG from pre-immune or PAX3-FKHR specific immune sera were included in reaction before to probe addition to confirm the presence of PAX3-FKHR in the complex (see arrow) (c) Sequence-specificity was tested by the ability of 10- and 100-fold excess unlabeled mutant gPFRE or unrelated E1 and MEF3 oligos to compete with the WT DNA probe for GST-PAX3-FKHR binding. (d) ChIP assays demonstrate in vivo interaction between PAX3-FKHR and myogenin promoter in C2 cells. Opposing arrows indicates locations of the primer sets used for PCR analysis.

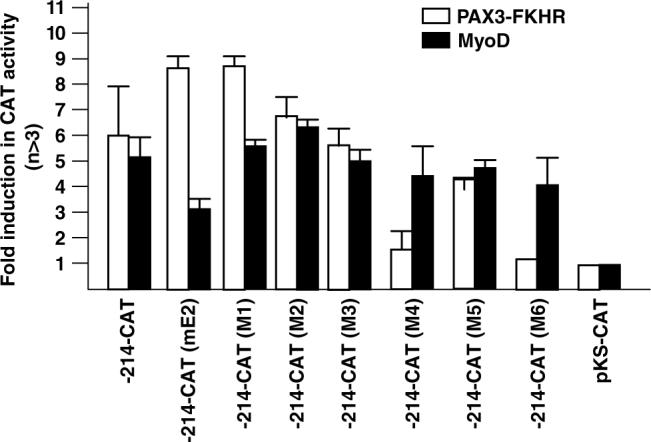

We confirmed the DNA binding results by evaluating the effect of these mutations on promoter transactivation by PAX3-FKHR (Figure 7). We included mutation of the E2 element as control. As predicted, the M4 and M6 mutations decreased PAX3-FKHR transactivation of myogenin. We suspect that the M4 site is the main contact point because the M5 mutation had only a modest effect on transactivation. Predictably, the gPFRE mutations had no effect on transactivation by MyoD.

Figure 7.

Effect of M1–M6 mutation on transactivation of the myogenin promoter by PAX3-FKHR. Transfection and CAT activity calculation were performed as described in Figure 3c.

Transactivation of the myogenin promoter by PAX3-FKHR depends on the paired DNA-binding domain

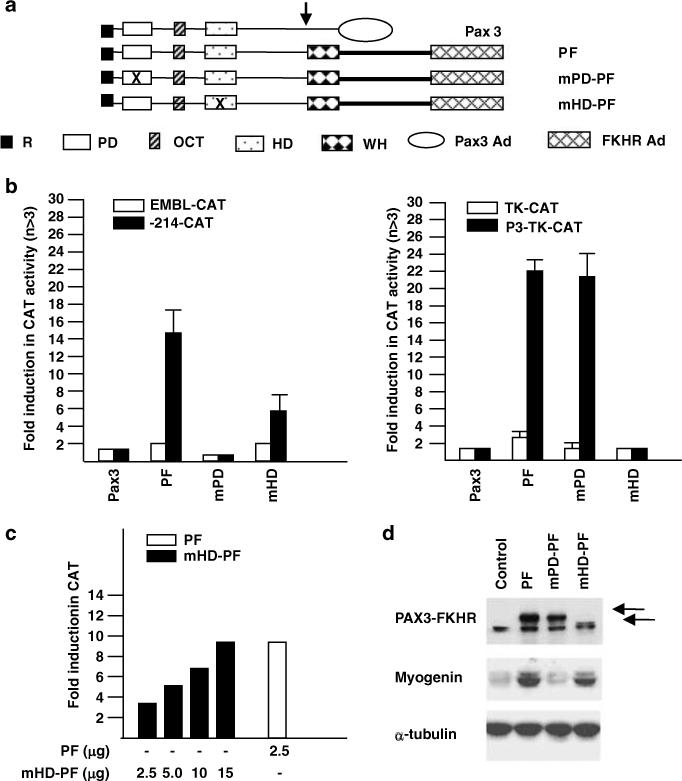

We investigated the requirements for the differential activity of PAX3-FKHR and Pax3 towards myogenin. Although both factors have identical DBDs, PAX3-FKHR has been reported to target genes that are not normally regulated by Pax3 (Epstein et al., 1998; Khan et al., 1999; Begum et al., 2005). For example, the absolute requirement for dual binding sites by Pax3 is relieved in PAX3-FKHR, which can activate target genes containing the dual-binding sites (c-met, Epstein et al., 1995) or only a palindromic HD-binding site in the PDGFαR promoter (Epstein et al., 1998). The following studies are designed to clarify (1) the DNA recognition specificity involved in myogenin activation by PAX3-FKHR (Figure 8), and (2) to evaluate the protein determinants in PAX3-FKHR associated with the relaxed target gene specificity (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 8.

Paired domain-dependent transactivation of the myogenin promoter by PAX3-FKHR. (a) Schematic illustration of Pax3, WT PAX3-FKHR (PF), paired domain PAX3-FKHR mutant (mPD-PF), and homeodomain PAX3-FKHR mutant (mHD-PF) constructs. The mPD-PF contains a deletion of the NH2-terminal α-helix of the PD; the mHD-PF contains a deletion of the entire HD (Epstein et al., 1998). R: repressor domain; PD: paired box domain; OCT: octapeptide sequence; HD: homeodomain domain; WH: bisected winged helix domain; Pax3AD: Pax3 activation domain; FKHRAD: FKHR activation domain. (b) Transactivation of the myogenin promoter (left panel) and of thymidine kinase (TK) promoter containing two tandem copies of PDGFαR P3 regulatory element (TAATCCCATTA, right panel) by WT and DBD mutants of PAX3-FKHR. Conditions for transfection and CAT activity calculation were as in Figure 3c. (c) Concentration-dependent transactivation of the myogenin promoter by mHD-PF protein. (d) Western blot analysis of endogenous myogenin gene expression in C2 cells by WT and DBD mutants of PAX3-FKHR.

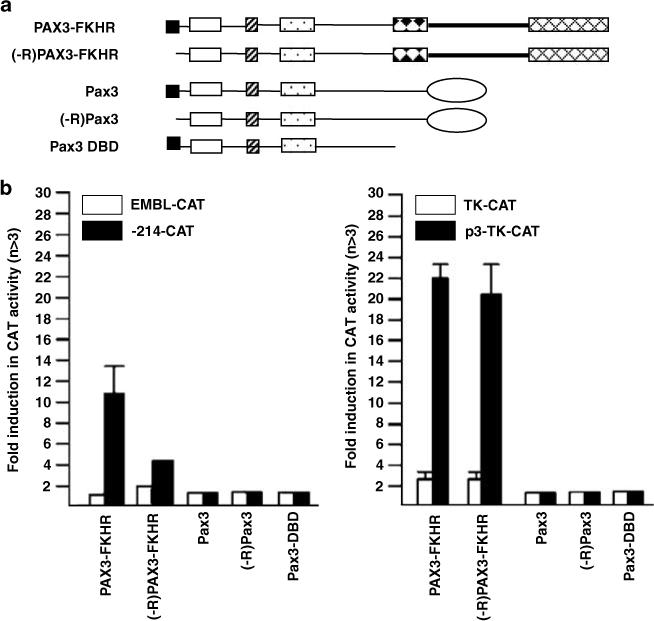

Figure 9.

Effect of the NH2-terminal R repressor domain on Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR transcriptional specificity. (a) Schematic illustration of Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR constructs with or without the R repressor domain. (b) Transactivation of myogenin (−214-CAT) and PDGFαR (P3-TK-CAT) promoter constructs by Pax3, (-R) Pax3, PAX3-FKHR, (-R) PAX3-FKHR, or Pax3DBD. Conditions for transfection and CAT activity calculation were as in Figure 3c.

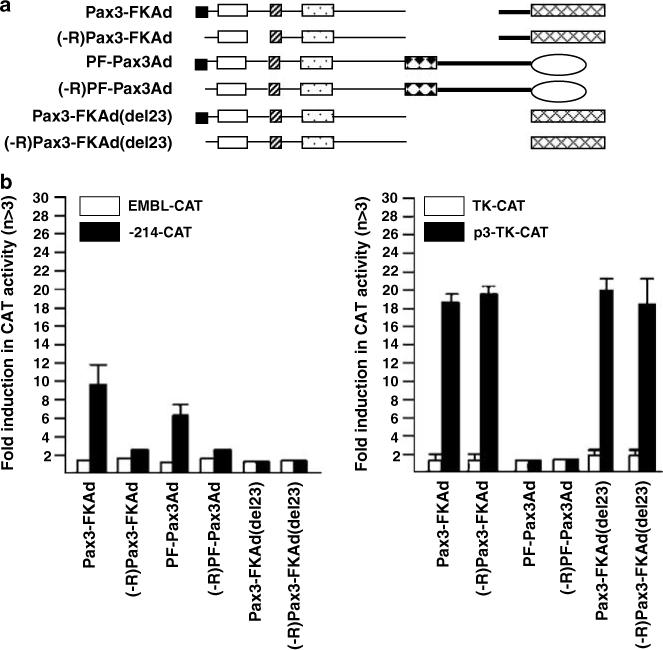

Figure 10.

Effect of activation domain substitution on Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR transcriptional specificity. (a) Schematic illustration of the AD replacement constructs of Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR with or without the R domain. (b) Transactivation of −214-CAT and P3-TK-CAT promoter constructs by the AD replacement constructs. Conditions for transfection and CAT activity calculation were as in Figure 3c.

We tested the transactivation activity of two PAX3-FKHR mutants, one with a mutation to the PD motif (mPD-PF) and the other with a mutation to the HD motif (mHD-PF) (Figure 8a). Mutation of PD abolished myogenin transactivation but had no effect on transactivation of the P3 response element from the PDGFαR promoter (Figure 8b). By contrast, mutation of HD had a minor effect on transactivation of myogenin whereas transactivation of the PDGFαR P3 site was abolished. Transactivation of the myogenin promoter by mHD-PF could be restored to the wild-type levels by increasing the amount of the expression vector (Figure 8c). Although mutation of HD reduced transactivation, it did not impair the induction of endogenous myogenin expression in C2 cells (Figure 8d). Deletion of the bisected non-functional winged helix FKHR DBD had no effect on PAX3-FKHR activity (data not shown). In all cases, neither myogenin nor PDGFαR was transactivated by Pax3. Thus, transactivation of myogenin by PAX3-FKHR requires the PD but not the HD motif.

A novel role of the Pax3 ‘R’ domain in regulating PAX3-FKHR gene targeting specificity

Lastly, we examined the basis for the autonomous PD activity in PAX3-FKHR. To address this question, we focused on two Pax3 protein determinants that have known negative regulatory functions on Pax3 transcription specificity, the N-terminal repressor R domain (Figure 9) and the AD (Figure 10). The R domain selectively inhibits Pax3 transactivation of promoters containing a composite PD/HD-response element (Chalepakis et al., 1994a). The Pax3 AD has a negative influence on the transactivation of promoters containing HD responsive element (Cao and Wang, 2000).

In Figure 9, we compared the effect of deleting R domain from Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR (Figure 9a) on transactivation of promoters containing either HD (PDGFαR P3) or PD (myogenin)-binding sites. Deletion of the R domain did not change Pax3 transactivation of either promoter (Figure 9b). However, removal of the R domain from PAX3-FKHR reduced myogenin transactivation (left panel) but did not affect transactivation of P3-TK (right panel). Deletion of the FKHR portion of PAX3-FKHR (Pax3-DBD) completely abolished transactivation of both promoters, indicating that DNA binding alone was not capable of transactivation. We speculated that the selective influence of the R domain on the PD function might result from crosstalk, directly or indirectly, with the Pax3 AD or with the FKHR motifs. We generated a series of PAX3-FKHR chimeric proteins to assess the role of these regions in PAX3-FKHR function (Figure 10a). Pax3-FKAd chimera that contained Pax3 DBD directly fused to with the C-terminal half of FKHR protein (the FKHR AD and a 189 amino acid FKHR linker immediately upstream of it) was able to transactivate both promoters (Figure 10b). By contrast, the PF-Pax3Ad chimera that replaced the FKHR AD with the Pax3 AD transactivated the myogenin but not the PDGFαR promoter. The type of AD associated with the DBDs appears unimportant for PD autonomy because both PAX3-FKHR and PF-Pax3Ad showed the same transcription specificity. Most significantly, both Pax3-FKAd and PF-Pax3Ad chimeras, like PAX3-FKHR, required the R domain for transactivation of myogenin promoter (Figure 10b). These studies imply that the FKHR linker is critical for PAX3-FKHR regulation of the myogenin prom oter because this region is the only difference between PF-Pax3Ad and Pax3. Indeed, deletion of this linker sequence as in Pax3-FKAd (del 23) completely abolished transactivation of myogenin, just like Pax3. By contrast, this deletion showed no effect on the transactivation of the PDGFαR element. Data presented in Figures 9 and 10 provide evidence for the first time that the Pax3 R domain and the FKHR linker domain play a regulatory role in the DNA recognition specificity of the PAX3-FKHR oncoprotein.

Discussion

The role of chimeric transcription factors created by chromosomal translocations in the etiology of several human cancers is well established. In the vast majority of cases, the fusion protein consists of the DBD of one transcription factor fused to the AD of a different transcription factor. Commonly, oncogenesis results from changes in temporal or spatial expression patterns or increased/decreased transcriptional activation by the fusion protein. The PAX3-FKHR fusion protein arises from a chromosomal translocation associated with the majority of aRMS tumors. The translocation fuses the N-terminus of Pax3 that contains a 10-amino acid repressor R domain and the DBDs (PD and HD) to the C-terminus of FKHR that contains a non-functional partial winged helix DBD, a 330amino-acid linker domain, and the FKHR AD. Initial studies suggested that the oncogenic properties of PAX3-FKHR derive from the FKHR AD, which is more potent than the Pax3 AD. However, recent work has shown that PAX3-FKHR can activate genes that are not normal targets for Pax3 activation.

In this study, we find that the non-DBD regions of Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR can alter the transcription target specificity of the Pax3 DBDs that are identical in the two molecules. As determined by EMSA, when Pax3 DBDs are expressed as separate polypeptides, each can recognize and bind to the cognate PD or HD response element. However, when PD and HD are expressed together as in the native Pax3, the protein can only bind and transactivate through DNA sites containing a composite PD/HD response element (Goulding et al., 1991), leading to the conclusion that Pax3 function requires synergy of its two DBDs. The same observation also raises the interesting possibility that each of the two DBDs possesses the intrinsic potential to act independent of each other when given the opportunity such as in the fusion protein. PAX3-FKHR has extended DNA recognition activities that are not shared by Pax3. In this report, we show that PAX3-FKHR can activate promoters that contain only a PD response element (e.g., myogenin, PD-dependent). Previously, we showed that PAX3-FKHR could activate promoters that contain only a HD response element (e.g., PDGFαR, HD-dependent, Epstein et al., 1998). Thus, the fusion process has enabled PAX3-FKHR to activate two additional sets of target genes that are not activated by Pax3, through modifying the PD and HD activity.

The structural requirements, i.e., protein domains, for PAX3-FKHR activation of HD response elements differed from those for activation of PD response elements. We have identified three domains of PAX3-FKHR that differentially affect activation of HD versus PD response element: the R domain, the FKHR linker domain, and the AD (Pax3 or FKHR). First, the Pax3 R domain and the FKHR linker domain are both absolutely required for PAX3-FKHR activation of a PD response element, but have no effect on activation of a HD response element (Figures 9 and 10). The participation of the R domain in only promoting autonomous PD activity is particularly intriguing because the R domain juxta-positions immediately upstream of the PD domain. Second, the FKHR AD is critical for HD-dependent activation, whereas the Pax3 AD can substitute for the FKHR AD in activation of a PD response element (Figure 8). Since Pax3 AD blocks HD-dependent transactivation by PAX3-FKHR, we believe removing the Pax3 AD is the key step for the fusion protein to gain access to HD autonomy. These varied requirements for transcriptional activation of HD- or PD-response elements suggest that there is an intricate interaction and communication between the different domains in PAX3-FKHR.

A simple model that can account for these findings is that the native PAX3-FKHR is structurally flexible and can adopt several distinct conformations. We hypothesize PAX3-FKHR assumes three distinct conformations, each associated with activation of one of the three PAX3-FKHR response elements, (i) PD/HD-dependent (Pax3) response elements, e.g., e5, c-met), (ii) HD response element (e.g., PDGFαR), and (iii) PD response element (e.g., myogenin). While not clear how the different conformations are stabilized, we imagine two possibilities. First, the AD is the main driving force in defining the binding specificity/or stability of the DBD of PAX3-FKHR towards different target sequences. In this case, the non-DBD of PAX3-FKHR determines whether it adopts a conformation that allows or prohibits binding to the three different response elements. Second, the Pax3 DBDs are sufficiently pliable to recognize and bind to the three different response elements. In this case, a specific conformation is induced depending on the nature of the binding site. Presumably, these conformational changes affect the ability of the AD to interact productively with other regulatory proteins. In the later case, it is plausible that the AD interacts with co-repressors when bound to one type of site whereas it interacts with coactivators when bound to other sites. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive and reality may actually involve both mechanisms. One could imagine that a weak or unstable DNA binding can be stabilized by protein–protein interactions involving AD interaction with other proteins at the promoter. While these two possibilities differ in the dominant role played by either determinant, it is without doubt that specificity of interaction between Pax3 DBDs and FKHR AD is defined by unique sequences/or structural configuration at the intra-molecular level as well as differential association with regulatory factors at the inter-molecular level. Future studies will be needed to address the specifics in these ‘structural’ changes as well as to identify other regulatory protein factors that are associated with these changes.

Morphologically, the aRMS tumors show the least differentiated phenotype among all the RMS subtypes. Hence, it is surprising that aRMS tumors express the highest levels of myogenin, a factor specifically associated with differentiated muscle cells. More curiously, MyoD the master regulator of myogenin transcription, although abundant, is transcriptionally inactive in aRMS cells (Tapscott et al., 1993; Weintraub et al., 1997; Puri et al., 2000). These observations leads to the hypothesis that aRMS cells arise either from myogenin positive muscle progenitors or from mature muscle cells that undergo de-differentiation upon oncogenic transformation. Alternatively, certain pathological events characteristic to aRMS might contribute to the enhanced levels of myogenin expression in this tumor subtype. The latter scenario is supported by the current study that directly links PAX3-FKHR to increased myogenin gene transcription. The fact that PAX3-FKHR effect can occur in undifferentiated myoblasts and is mediated by a novel cis-regulatory element independent of MyoD activity offers an alternative mechanism to account for aberrant myogenin expression in undifferentiated aRMS tumors.

PAX3-FKHR transactivates the myogenin promoter through direct interaction with gPFRE and requires the N-terminus of the PD motif. Although this sequence does not appear to resemble other PD binding sites that have been identified through in vitro oligos selection experiments rather than promoter analysis, the critical core sequence (M4: AAAC) is present in both human and mouse myogenin promoters. It is intriguing that mutation of the MEF3 and E1 sites within the myogenin promoter substantially reduced transactivation by PAX3-FKHR. The mutational and deletion studies suggest that E1 and MEF3 sites play an auxiliary role in potentiating PAX3-FKHR transactivation activity. Using co-immunoprecipitation assays, we tested the possibility of an interaction between PAX3-FKHR with Six and MyoD, proteins known to bind MEF3 and E1 sites, respectively. Our preliminary results show that PAX3-FKHR does not interact directly or indirectly with either protein in vitro and in vivo (data not shown). Given these caveats, we propose that gPFRE bound PAX3-FKHR may be interacting with a different set of proteins bound to the E1 and MEF3 elements. Since the PAX3-FKHR effect is cell-type specific, these unknown proteins are likely to be commonly expressed/or activated only in committed myogenic cells (C2, RD) and mesenchymal stem cells (10T1/2). Further work is required to investigate the precise nature of proteins that bind to E1 and MEF3 sites of myogenin promoter in the presence of PAX3-FKHR.

In conclusion, these studies delineate the mechanism involved in the up-regulation of myogenin gene by PAX3-FKHR. While all transcription factors contain minimally a DBD and an AD that can be readily swapped with little or no apparent affect on function, results from our chimeric protein studies reveal that a complex interaction between these two domains plays a significant role in defining the transcriptional specificity of chimeric transcription factor PAX3-FKHR. The current report offers insights into the different mechanisms required for PAX3-FKHR to regulate new classes of target genes that normally are not affected by the parental proteins. Moreover, we find in preliminary study that the tumorogenic properties of PAX3-FKHR are maintained in C2 cells expressing PAX3-FKHR mutants that retain single binding capability to either HD or PD response elements (Zhang and Wang, unpublished data). It will be important in future studies to identify additional target genes that are specifically activated by either HD-dependent or PD-dependent PAX3-FKHR action because it is likely that these genes are the main targets for PAX3-FKHR oncogenesis.

Materials and methods

Reagents

DNA constructs containing human myogenin promoter driven CAT construct (−214-CAT and −121-CAT) were from Dr Strasberger (University of Braunschweig) and MyoD from Dr Epstein (University of Pennsylvania). Myogenin promoter deletion constructs were generated using Eraser-base system (Promega). Constructs containing Pax3, wild-type and mutant variants of PAX3-FKHR, and P3-TKCAT were as described (Epstein et al., 1998). Antibody specific for Pax3 and PAX3-FKHR was developed from immunizing rabbits with purified GST-PAX3-FKHR protein, and then purified on protein A column (Pierce). Antibodies specific for MyoD (5.8A) and myogenin (F5D) were from pharmingen, and α-tubulin (CP06) from Oncogene.

Cell culture

All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle's high glucose medium containing 10% bovine calf serum (NIH3T3), 10% fetal bovine serum (HeLa, RD2, C3H-10T1/2, human foreskin diploid fibroblast HF), or 15% fetal calf serum (C2). C2C12 differentiation was induced by 2% horse serum (HS) containing medium. Retroviruses expression vectors were previously described (Cao and Wang, 2000). Stable puromycin-resistant transfectants were selected; at least five single clones and a pooled population were analysed.

CAT assay

Cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per 100 mm tissue culture dish 24 h before transfection. Transient transfection was carried out with 20 μg of total DNA including 1 μg of CMV-β-galactosidase DNA as an internal standard for monitoring transfection efficiency. Cell lysates for LacZ and CAT assays were prepared as described (Cao and Wang, 2000). Mutations of myogenin promoter-CAT constructs were introduced using the Quick-change system (Stratagene) with primers shown in Supplements. Quantitative analysis of CAT activity was determined by phosphoimager.

EMSA and northern

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed by pre-incubating bacterial expressed GST-PAX3-FKHR (50 ng) or nuclear extract (10 μg) with non-specific salmon sperm DNA (0.05 μg/ml) as described (Epstein et al., 1998). Total RNA was prepared using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and analysed by Northern analysis (Zhang and Wang, 2006).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Myogenin-ChIP analysis was carried out using a total of 1 × 108 PAX3-FKHR expressing C2 cells as described (Zhang and Wang, 2006). Extract containing sheared DNA was pre-cleared with protein-A then immunoprecipitated by PAX3-FKHR-specific antibody (3 μg/ml) After removal of crosslinks and deproteinization by proteinase K, genomic DNA was purified (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and analysed by PCR as described. Myogenin primers are shown in Supplements. A fraction of the pre-cleared extract served as total input control.

Antisense oligonucleotide and transfection

The Antisense oligonucleotide (AS-ODN) (sequence shown in Supplements) used to knockdown PAX3-FKHR was synthesized as s-oligos and purified by HPLC. RH30 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in six-well plates one day before lipofectamine (Invitrogen) transfection. Cells were harvested 48-h post-transfection.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Reed Graves for the critical review of this manuscript. The work is supported by NIH grant (CA074907).

Supplementary Material

References

- Anderson J, Ramsay A, Gould S, Pritchard-Jones K. Embryonic expression of the tumor-associated PAX3-FKHR fusion protein interferes with the developmental functions of Pax3. Am J Path. 2001;159:1089–1096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FG. Fusions involving paired box and fork head family transcription factors in the pediatric cancer alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Curr Topics Micro Immun. 1997;220:113–129. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60479-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FG, Galili N, Holick J, Biegel JA, Rovera G, Emanuel BS. Rearrangement of the PAX3 paired box gene in the paediatric solid tumour alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Genet. 1993;3:113–117. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum S, Emani N, Cheung A, Wilkins O, Der S, Hamel PA. Cell-type-specific regulation of distinct sets of gene targets by Pax3 and Pax3/FKHR. Oncogene. 2005;24:1860–1872. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi M, Remppis A, Fredericks WJ, Rauscher III FJ, Schafer BW. Induction of apoptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma cells through down-regulation of PAX proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13164–13169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchberger A, Ragge K, Arnold HH. The myogenin gene is activated during myocyte differentiation by pre-existing, not newly synthesized transcription factor MEF-2. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17289–17296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Wang C. The COOH-terminal transactivation domain plays a key role in regulating the in vitro and in vivo function of Pax3 homeodomain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9854–9862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalepakis G, Goulding M, Read A, Strachan R, Gruss P. Moleulcar basis of splotch and Waardenburg Pax-3 mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994a;91:3685–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalepakis G, Jones FS, Eelman GM, Gruss P. Pax-3 contains domains for transcription activation and transcription inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994b;91:12745–12749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalepakis G, Gruss P. Identification of DNA recognition sequences for the Pax3 paired domain. Gene. 1995;162:267–270. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TC, Hanley TA, Mudd J, Merlie JP, Olson EN. Mapping of myogenin transcription during embryogenesis using transgenes linked to the myogenin control region. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1649–1656. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TC, Wallace MC, Merlie JP, Olson EN. Separable regulatory elements governing myogenin transcription in mouse embryogenesis. Science. 1993;261:215–218. doi: 10.1126/science.8392225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pitta C, Tombolan L, Albiero G, Sartori F, Romualdi C, Jurman G, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies potential relevant genes in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma pathogenesis and discriminates PAX3-FKHR positive and negative tumors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2772–2781. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias P, Chen B, Dilday B, Palmer H, Hosoi H, Singh S, et al. Strong immunostaining for myogenin in rhabdomyosarcoma is significantly associated with tumors of the alveolar subclass. Am J Path. 2000;156:399–408. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64743-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass EC, Valentine M, Etcubanas E, Parham D, Webber BL, Houghton PJ, et al. A specific abnormality in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cyto Cell Genet. 1987;45:148–155. doi: 10.1159/000132446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Lam P, Jepeal L, Maas RL, Shapiro DN. Pax3 inhibits myogenic differentiation of cultured myoblast cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11719–11722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Song B, Lakkis M, Wang C. Tumor-specific PAX3-FKHR transcription factor, but not PAX3, activates the platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4118–4130. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folpe AL. MyoD1 and myogenin expression in human neoplasia: a review and update. Adv Anat Path. 2002;9:198–203. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks WJ, Galili N, Mukhopadhyay S, Rovera G, Bennicelli J, Barr FG, et al. The PAX3-FKHR fusion protein created by the t(2;13) translocation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas is a more potent transcriptional activator than PAX3. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1522–1535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding MD, Chalepakis G, Deutsch U, Erselius JR, Gruss P. Pax3, a novel murine DNA binding proein expressed duringearly neurogeneisis. EMBO J. 1991;10:1135–1147. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostein I, Andraud-Fregeville M, Guillou L, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Deminiere C, Ranchere D, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma: value of myogenin expression analysis and molecular testing in diagnosing the alveolar subtype: an analysis of 109 paraffin-embedded specimens. Cancer. 2004;101:2817–2824. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen Y, Weintraub H, Benezra R. Overexpression of Id protein inhibits the muscle differentiation program: in vivo association of Id with E2A proteins. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1466–1479. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Arenkiel BR, Coffin CM, El-Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Capecchi MR. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes Dev. 2004a;18:2614–2626. doi: 10.1101/gad.1244004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Hansen MS, Coffin CM, Capecchi MR. Pax3:Fkhr interferes with embryonic Pax3 and Pax7 function: implications for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cell of origin. Genes Dev. 2004b;18:2608–2613. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan J, Bittner ML, Sall LH, Teichmann U, Azorsa DO, Gooden GC, et al. cDNA microarrays detect activation of a myogenic transcription program by the PAX3-FKHR fusion oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13264–13269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam PYP, Sublett JE, Hollenbach AD, Roussel MF. The oncogenic potential of the PAX3-FKHR fusion protein requires the Pax3 homeodomain recognition helix but not the Pax3 paired-Box DNA binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:594–601. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Huang CF, Schmidt J. The role of the CANNTG promoter element (E box) and the myocyte-enhancer-binding-factor-2 (MEF-2) site in the transcriptional regulation of the chick myogenin gene. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelagnoli MP, Burchill SA, Cullinane C, Selby PJ, Lewis IJ. Myogenin–a more specific target for RT-PCR detection of rhabdomyosarcoma than MyoD1. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:1–8. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri PL, Wu Z, Zhang P, Wood LD, Bhakta KS, Han J, et al. Induction of terminal differentiation by constitutive activation of p38 MAP kinase in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Genes Dev. 2000;14:574–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidler S, Fredericks WJ, Rauscher JF, Barr GF, Vogt PK. The hybrid PAX3-FKHR fusion protein of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma transforms fibroblasts in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9805–9809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DN, Sublett JE, Li B, Downing JR, Naeve CW. Fusion of PAX3 to a member of the Forkhead family of transcripton factors in human alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5108–5112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer DB, Rhee J, Cheung WL, Lassar AB. Inhibition of myogenic bHLH and MEF2 transcription factors by the bHLH protein Twist. Science. 1996;272:1476–1480. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz F, Demignon J, Porteu A, Kahn A, Concordet JP, Daegelen D, et al. Expression of myogenin during embryogenesis is controlled by Six/sine oculis homeoproteins through a conserved MEF3 binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14220–14225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott SJ, Thayer MJ, Weintraub H. Deficiency in rhabdomyosarcomas of a factor required for MyoD activity and myogenesis. Science. 1993;259:1450–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.8383879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turc-Carel C, Lizard-Nacol S, Justrabo E, Favrot M, Tabone E. Consistent chromosomal translocation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Genet Cyotgeneti. 1986;19:361–362. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(86)90069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang-Wuu S, Soukup S, Ballard E, Gotwals B, Lampkin B. Chromosomal analysis of sixteen human rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1988;48:983–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub M, Kalebic T, Helman JL, Bhatia GK. Disruption of the MyoD/p21 pathway in rhabdomyosarcoma. Sarcoma. 1997;1:135–141. doi: 10.1080/13577149778218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee SP, Rigby PW. The regulation of myogenin gene expression during the embryonic development of the mouse. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1277–1289. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Wang C. F-box protein Skp2: a novel transcriptional target of E2F. Oncogene. 2006;25:2615–2627. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.