Abstract

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are, together with copy number variation, the primary source of variation in the human genome. SNPs are associated with altered response to drug treatment, susceptibility to disease and other phenotypic variation. Furthermore, during genetic screens for disease-associated mutations in groups of patients and control individuals, the distinction between disease causing mutation and polymorphism is often unclear. Annotation of the functional and structural implications of single nucleotide changes thus provides valuable information to interpret and guide experiments. The SNPeffect and PupaSuite databases are now synchronized to deliver annotations for both non-coding and coding SNP, as well as annotations for the SwissProt set of human disease mutations. In addition, SNPeffect now contains predictions of Tango2: an improved aggregation detector, and Waltz: a novel predictor of amyloid-forming sequences, as well as improved predictors for regions that are recognized by the Hsp70 family of chaperones. The new PupaSuite version incorporates predictions for SNPs in silencers and miRNAs including their targets, as well as additional methods for predicting SNPs in TFBSs and splice sites. Also predictions for mouse and rat genomes have been added. In addition, a PupaSuite web service has been developed to enable data access, programmatically. The combined database holds annotations for 4 965 073 regulatory as well as 133 505 coding human SNPs and 14 935 disease mutations, and phenotypic descriptions of 43 797 human proteins and is accessible via http://snpeffect.vib.be and http://pupasuite.bioinfo.cipf.es/.

INTRODUCTION

With the completion of the sequencing of the human genome, much attention has been centered on the study of human genome variability. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common source of human genetic variation, and are undoubtedly a valuable resource for investigating the genetic basis of diseases. SNPs, together with DNA copy number variations (CNVs), have become one of the most actively researched areas of genomics in recent years (1,2).

In this article, we focus on the smaller of these two types of variation, SNPs. Single nucleotide polymorphisms are highly abundant, stable and distributed throughout the genome. This type of variation is associated with diversity in the population, individuality, and although the majority of these variations probably result in neutral phenotypic outcomes, certain polymorphisms can predispose individuals to disease, or influence its severity, progression or individual response to medicine. Viewed at the molecular level, these functional SNPs can affect the human phenotype by interfering on both levels of the protein synthesis machinery: non-coding SNPs may disrupt transcription factor binding sites, splice sites and other functional sites on the transcriptional level, whereas coding SNPs can cause an amino acid change and alter the functional or structural properties of the translated protein. Annotating the way a polymorphism affects an individual's phenotype should therefore focus on both levels: describing the effects on the gene's and the protein's properties. To this end, we merged two databases that each focus on one of these levels: PupaSuite (3) and SNPeffect (4,5).

PupaSuite is a web tool for selecting SNPs with potential phenotypic effect and was originally based on the combined functionality of the PupaSNP (6) and PupasView (7) web tools. Since its release in 2006, PupaSuite was extended with new tools for predicting silencers and enhancers, new conservation measures and predictions on mouse and rat genomes. SNPeffect focuses on the functional annotation of non-synonymous coding SNPs in human proteomes, but now also includes predictions on known disease mutations from the UniProt Knowledge Base.

ADDITIONS TO SNP ANNOTATION

SNPeffect 3.0 novelties

SNPeffect focuses on the molecular phenotypes of variants, and includes details on structural, functional and cellular effects on the amino acid change of a non-synonymous coding SNP. Destabilizing variations which affect the aggregation behavior of a protein can be potentially disease causing and therefore are of particular interest to researchers. By investigating polymorphisms on a large scale and providing their phenotypic effects together with the ability to filter out specific functional or structural changes, researchers are able to select potentially interesting polymorphisms for further analysis.

Waltz and Tango, two aggregation predictors based on physical properties

The Waltz algorithm combines sequence, physical properties and structural parameters to identify motifs that can nucleate amyloid fiber formation in proteins (Maurer-Stroh et al., submitted for publication). Special emphasis is made to minimize overprediction of amorphous beta aggregation compared to the highly regular cross-beta structure of amyloid fibrils. Creation of new amyloidogenic motifs through nsSNPs is implicated in amyloid deposit diseases. The statistical mechanics algorithm Tango, on the other hand, predicts protein regions that are prone to form amorphous beta aggregates. Included in Tango2 is an improved prediction of mutation effects on aggregation, transmembrane region stability and signal peptide disruption. Both Waltz amylogenic regions and Tango aggregating regions are available as annotations via ProteinDAS servers at the DAS registry at the European Bioinformatics Institute.

Hsp70 chaperone family-binding predictor

A DnaK-binding site predictor was built using a dual method combining sequence and structural information. Experimental DnaK-binding data of 53 non-redundant peptide sequences allowed us to generate a sequence-based position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) based on logarithm of the odds scores. Following an in silico alanine scan of the substrate peptide in the crystal structure of a DnaK-substrate complex [1dkx, (8)] using the FoldX force field (9), we generated a structure-based PSSM that reflects the individual contribution of certain substrate residue types for DnaK binding. Upon adding the structure-based PSSM with a normalization factor of 0.2 to the sequence-based PSSM, we obtained a DnaK motif predictor that was able to correctly predict 89% of the true positives in the tested peptide set (high sensitivity), with a concurrent amount of only 5.9% false positives for a specific score threshold (high specificity). To assess the robustness of the predictor, we carried out a cross-validation by leaving out each sequence from the learning set together with its close homologs and calculating the rate of repredicting them. This resulted in a prediction accuracy of 72% true positives and 5.9% false positives. The predictor was able to identify an entire known DnaK-binding site in the heat-shock promoter σ32(10).

UniProt disease mutations

The new data source included in SNPeffect, the human dataset available in the UniProt knowledge base (11) version 52.0 (March 2007), enables us to show results on a set of known disease mutations (Table 1). Functional and structural annotations of known disease mutations are of particular interest as they can help direct experimental setup for the elucidation of the molecular mechanism of disease.

Table 1.

Statistics on putative deleterious SNPs and the affected phenotypic property as annotated by the SNPeffect and PupaSuite databases, and SNPeffect annotation results for known human disease mutations from the Uniprot Knowledge Base release 52.0

| Property | Number of SNPs analysed | Number of SNPs affected | % SNPs affected | Number of Disease mutations analyzed | Number of Disease mutations affected | % Disease mutations affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PupaSuite | ||||||

| Ensembl regulatory SNPs | ||||||

| Exonic splicing - Silencers | 275 189 | 24 329 | 8.8 | – | – | – |

| Exonic splicing - Enhancers | 275 189 | 111 814 | 40.6 | – | – | – |

| TFBS-TRANSFAC | 604 772 | 110 488 | 18.3 | – | – | – |

| TFBS-JASPAR | 604 772 | 61 070 | 10.1 | – | – | – |

| Splice sites | 4 043 130 | 1716 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Splice sites (GeneID) | 4 965 073 | 13 697 | 0.3 | – | – | – |

| Triplex | 4 757 372 | 457 631 | 9.6 | – | – | – |

| miRNAs | 112 330 | 21 029 | 18.7 | – | – | – |

| Selective pressure at codon level (ω) | 72 220 | 22 138 | 30.7 | – | – | – |

| Total PupaSuite | 4 965 073 | 749 603 | 15.1 | – | – | – |

| SNPeffect | – | – | – | |||

| Ensembl non-synonymous coding SNPs | SwissProt variation index (Disease) | |||||

| Tango | 132 748 | 830 | 0.6 | 14 935 | 687 | 4.6 |

| Waltz | 133 505 | 6291 | 4.7 | 14 935 | 881 | 5.9 |

| DnaK binding | 133 505 | 11 658 | 8.7 | 14 935 | 1322 | 8.9 |

| FoldX | 8321 | 541a | 6.5 | |||

| Phobius | 133 505 | 37 325 | 28 | 14 935 | 668 | 4.5 |

| Protein turnover | 133 505 | 582 | 0.4 | 14 935 | 6 | 0 |

| Farnesylation | 133 505 | 13 | 0 | 14 935 | 182 | 1.2 |

| Myristoylation | 133 505 | 14 | 0 | 14 935 | 75 | 0.5 |

| GPI-anchoring | 133 505 | 24 | 0 | 14 935 | 219 | 1.5 |

| PTS1 peroxisomal targeting | 133 505 | 63 | 0 | 14 935 | 732 | 4.9 |

| TypeI geranylgeranylation | 133 505 | 4 | 0 | 14 935 | 119 | 0.8 |

| TypeII geranylgeranylation | 133 505 | 0 | 0 | 14 935 | 13 | 0.1 |

| Psort | 133 554 | 2182 | 1.6 | 14 935 | 232 | 1.6 |

| CSA literature | 72 225 | 0 | 0 | 14 935 | 0 | 0.3 |

| CSA extended | 72 225 | 13 | 0 | 14 935 | 44 | 0 |

| NetAcet 1.0 | 72 225 | 18 | 0 | 14 935 | 1 | 0 |

| NetNES 1.1 | 72 225 | 270 | 0.4 | 14 935 | 38 | 0.3 |

| NetNGlyc 1.0 | 72 225 | 22 | 0 | 14 935 | 25 | 0.2 |

| NetOGlyc 3.1 | 72 225 | 114 | 0.2 | 14 935 | 6 | 0 |

| NetPhos 2.0 | 72 225 | 1822 | 2.5 | 14 935 | 293 | 2 |

| ProP 1.0 | 72 225 | 5489 | 7.6 | 14 935 | 256 | 1.7 |

| SignalP 3.0 | 72 225 | 790 | 1.1 | 14 935 | 190 | 1.3 |

| TMHMM 2.0 | 72 225 | 54 | 0.1 | 14 935 | 95 | 0.6 |

| Total SNPeffect | 133 505 | 31 415 | 23.5 | 14 935 | 3660 | 24.5 |

| All phenotypic properties combined | 5 098 578 | 784 107 | 15.4 | 14 935 | 3660 | 24.5 |

aNot all modeling runs were completed at the time of submission, this number may increase.

Full references for the tools applied to the data can be found in Supplementary Data.

Additional protein level annotations

Several protein functional annotations were added via the DAS registry at the EBI. A detailed list of annotations provided through a ProteinDAS service is listed in Supplementary Table 2. Additional sequence and structure based tools and databases used to describe variations and proteins in the SNPeffect dataset are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

PupaSuite enhancements

While much attention has been focused on the effects of variation on the amino acid sequence, variations that disrupt gene regulation, expression or splicing can dramatically impact gene function. PupaSuite focuses mainly on the possible effect of these regulatory variations. In this new version of PupaSuite, the database has been updated to analyze the complete set of SNPs cataloged in version 44 of Ensembl (12), which includes dbSNP (13) 126 genotype data and Sanger-caller Celera SNPs. Together with the prediction methods already included, some novel features have been added in this release.

Exonic splicing silencers (ESS)

ESSs are cis-regulatory elements located in coding regions that inhibit the use of adjacent splice sites, often contributing to alternative splicing. Wang et al. (14) described a list of 103 hexamers (the FAS-hex-3 set) identified as ESS candidates by genetic selection; we scanned the exon sequences of all the human genes to identify putative ESSs from Wang's set. SNPs located at these motifs are cataloged as potential SNPs that could disturb the silencer activity. To make prediction more reliable, the tool allows the search to be done in conserved regions.

Transcription factor binding sites

A complementary approach for TFBS identification has been included, which uses the position weight matrices (PWM) deposited in JASPAR (15). JASPAR is an open-access database of annotated, high-quality, matrix-based transcription factor binding site profiles for multicellular eukaryotes. It contains models derived from 111 profiles that were exclusively derived from published collections of experimentally defined TFBSs for multicellular eukaryotes. We use the matrices corresponding to vertebrates to search for TFBSs in the 5 kb upstream region of all the human genes. To this end, we use MatScan (http://genome.imim.es), a program to search binding sites in genomic sequences. Since MatScan does not allow a cutoff to minimize false positives, we also use the Meta program (http://genome.imim.es) to filter the results by searching the coincidences of TFBSs in orthologous genes in mouse.

Prediction of new splice sites

Gene ID (16) is a program to predict genes in genomic sequences, where splice sites, and start and stop codons are predicted and scored along the sequence using PWMs. We use this program to scan the whole genome to find new splice sites and to map SNPs that could have a putative effect in the disruption of these important sites.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

miRNAs act as repressors of protein-coding genes by binding to target sites in the 3′ UTR of mRNAs. In this release, we scan the genome to find SNPs located at miRNAs. Besides, we use miRanda (14), an algorithm for the detection of potential microRNA target sites in genomic sequences, to localize all the SNPs situated in the region 3′ UTR of these targets sites. Both SNPs at miRNAs and SNPs in their target sequences could have an effect in the normal function of these regulatory elements. This effect is measured by the difference of scores among the alleles of the SNPs.

Mouse and rat genomes

Finally, this new release of PupaSuite incorporates the analysis of genetic variations for mouse and rat genomes. Because most of the methods include PWMs for vertebrates, most of the predictions can be extrapolated and the search of regulatory elements can be done in these genomes. Predictions for exonic splicing enhancers and silencers are not extrapolated since the proteins used for building the PWMs correspond exclusively to human proteins. With the inclusion of this information, the tool can aid to better understand the functional diversity in different genomes.

PupaSuite web service

In addition to the updated web page interface, a set of public web services, implemented in Java, have also been developed. These web services constitute a complete and exhaustive API to access all the functional data showed in the web page

An example of how to use the PupaSuite web services is included in the Supplementary Data.

Availability of the databases

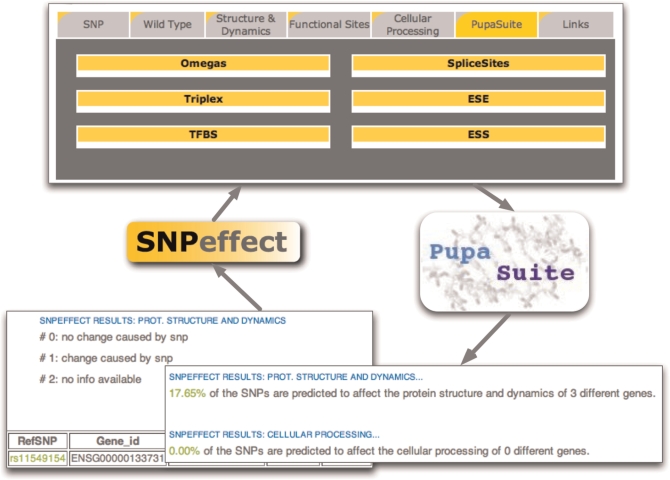

The merge of the SNPeffect and PupaSuite databases includes accessibility of the combined data through both portals (at: http://snpeffect.vib.be and http://pupasuite.bioinfo.cipf.es/). PupaSuite data are accessible through the SNPeffect interface and vice versa (Figure 1). Both databases are freely available for academic users. Help pages on both servers provide detailed information on usage of the interfaces. SNPeffect and PupaSuite will be updated with each even version release of Ensembl, which corresponds to a four-monthly update.

Figure 1.

Viewing PupaSuite annotation results in SNPeffect and vice versa.

DISCUSSION

Nowadays, more than 11 million SNPs have been described in databases like dbSNP. Among them, thousands of SNPs can have a direct impact on disease. Recently, different bioinformatics tools have been developed which try to find these putative disruptive polymorphisms. These tools use different information based on sequence, structure, conservation or functional properties to distinguish disease-causing mutations from those that are thought to have a neutral effect. Because of its importance on biomedical research, it would be beneficial to generate bioinformatics tools to extract and merge interesting data coming from these heterogeneous sources, and collect these results in a single database. SNPeffect and PupaSuite are two of the most complete bioinformatics tools for the analysis of SNPs. Both tools integrate different methods for the analysis of SNPs, focusing on different levels of the protein synthesis machinery: (i) SNPeffect focuses on SNPs in gene-coding regions that can lead to changes in the biological properties of the encoded protein, (ii) PupaSuite focuses on SNPs in non-coding gene regulatory regions which may affect gene expression levels and mRNA stability. In this article, we present a joint effort for the integration of both tools, which has lead to the creation of a comprehensive database of putative functional polymorphisms. This way 749 603 regulatory human SNPs and 31 415 non-synonymous coding human SNPs were annotated as putative disruptive polymorphisms, and the same procedure resulted in the suggestion of a molecular mechanism of disease for 3660 known human disease mutations.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The VIB Switch laboratory was supported by a grant from the Federal Office for Scientific Affairs, Belgium (IUAP P6/43) and the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO Vlaanderen), Flanders. S.M.-S. was supported by a Marie Curie Intra-European fellowship. J.V.D. was supported by a grant from the Fund for Scientific Research, Flanders. L.C. was supported by a fellowship from CeGen (Genoma España), Spain. I.M. was supported by a fellowship from CIBER, Spain. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by a grant from the Federal Office of Scientific Affairs, Belgium (IUAP6/43).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feuk L, Carson AR, Scherer SW. Structural variation in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nrg1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stranger BE, Forrest MS, Dunning M, Ingle CE, Beazley C, Thorne N, Redon R, Bird CP, de Grassi A, et al. Relative impact of nucleotide and copy number variation on gene expression phenotypes. Science. 2007;315:848–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1136678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conde L, Vaquerizas JM, Dopazo H, Arbiza L, Reumers J, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Dopazo J. PupaSuite: finding functional single nucleotide polymorphisms for large-scale genotyping purposes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W621–W625. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reumers J, Maurer-Stroh S, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F. SNPeffect v2.0: a new step in investigating the molecular phenotypic effects of human non-synonymous SNPs. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2183–2185. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reumers J, Schymkowitz J, Ferkinghoff-Borg J, Stricher F, Serrano L, Rousseau F. SNPeffect: a database mapping molecular phenotypic effects of human non-synonymous coding SNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D527–D532. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conde L, Vaquerizas JM, Santoyo J, Al-Shahrour F, Ruiz-Llorente S, Robledo M, Dopazo J. PupaSNP Finder: a web tool for finding SNPs with putative effect at transcriptional level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W242–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conde L, Vaquerizas JM, Ferrer-Costa C, de la Cruz X, Orozco M, Dopazo J. PupasView: a visual tool for selecting suitable SNPs, with putative pathological effect in genes, for genotyping purposes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W501–W505. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu X, Zhao X, Burkholder WF, Gragerov A, Ogata CM, Gottesman ME, Hendrickson WA. Structural analysis of substrate binding by the molecular chaperone DnaK. Science. 1996;272:1606–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schymkowitz JW, Rousseau F, Martins IC, Ferkinghoff-Borg J, Stricher F, Serrano L. Prediction of water and metal binding sites and their affinities by using the Fold-X force field. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10147–10152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501980102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarty JS, Rudiger S, Schonfeld HJ, Schneider-Mergener J, Nakahigashi K, Yura T, Bukau B. Regulatory region C of the E. coli heat shock transcription factor, sigma32, constitutes a DnaK binding site and is conserved among eubacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;256:829–837. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The UniProt Consortium. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D193–D197. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbard TJ, Aken BL, Beal K, Ballester B, Caccamo M, Chen Y, Clarke L, Coates G, Cunningham F, et al. Ensembl 2007. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D610–D617. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Rolish ME, Yeo G, Tung V, Mawson M, Burge CB. Systematic identification and analysis of exonic splicing silencers. Cell. 2004;119:831–845. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engstrom P, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B. JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D91–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guigo R. Assembling genes from predicted exons in linear time with dynamic programming. J. Comput. Biol. 1998;5:681–702. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1998.5.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]