Abstract

During αβ thymocyte development, clonotype-independent CD3 complexes are expressed at the cell surface before the pre-T cell receptor (TCR). Signaling through clonotype-independent CD3 complexes is required for expression of rearranged TCRβ genes. On expression of a TCRβ polypeptide chain, the pre-TCR is assembled, and TCRβ locus allelic exclusion is established. We investigated the putative contribution of clonotype-independent CD3 complex signaling to TCRβ locus allelic exclusion in mice single-deficient or double-deficient for CD3ζ/η and/or p56lck. These mice display defects in the expression of endogenous TCRβ genes in immature thymocytes, proportional to the severity of CD3 complex malfunction. Exclusion of endogenous TCRβ VDJ (variable, diversity, joining) rearrangements by a functional TCRβ transgene was severely compromised in the single-deficient and double-deficient mutant mice. In contrast to wild-type mice, most of the CD25+ double-negative (DN) thymocytes of the mutant mice failed to express the TCRβ transgene, suggesting defective expression of the TCRβ transgene similar to endogenous TCRβ genes. In the mutant mice, a proportion of CD25+ DN thymocytes that failed to express the transgene expressed endogenous TCRβ polypeptide chains. Many double-positive cells of the mutant mice coexpressed endogenous and transgenic TCRβ chains or more than one endogenous TCRβ chain. The data suggest that signaling through clonotype-independent CD3 complexes may contribute to allelic exclusion of the TCRβ locus by inducing the expression of rearranged TCRβ genes in CD25+ DN thymocytes.

Keywords: thymus, T cell development, CD3ζ, p56lck, clonotype-independent CD3 complexes

During development in the thymus, αβ T lineage cells pass through two phases of T cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement: The TCRβ genes rearrange first, during the CD4−8− double-negative (DN) stage. Thymocytes that have generated a productive TCRβ VDJ (variable, diversity, joining) gene express the pre-TCR on the cell surface, consisting of a TCRβ chain, a surrogate TCRα chain termed pre-Tα, and components of the CD3 complex. Signal transduction through the pre-TCR/CD3 complex drives maturation to the CD4+8+ double-positive (DP) stage, the TCRα genes rearrange, and the thymocytes first display the mature αβTCR (reviewed in refs. 1–4).

Pre-TCR dependent maturation is associated with a complex pattern of changes in cellular genetics, physiology, and phenotype (reviewed in refs. 5–7). A pivotal component in this process is the arrest of further TCRβ rearrangements resulting in allelic exclusion (8). Positive evidence that TCRβ locus allelic exclusion depends on pre-TCR/CD3 signaling comes from several experimental approaches, including introduction of TCRβ transgenes (9), antibody-mediated CD3ɛ crosslinking (10, 11), or genetic manipulations of CD3-associated signaling components (12–14). TCRβ VDJ rearrangements were inhibited in thymocytes of wild-type (wt) mice by anti-CD3ɛ crosslinking (10, 11), as well as in transgenic mice expressing a constitutively active p56lck (Lck) isoform (12). Moreover, inhibition of endogenous rearrangements by a TCRβ transgene was abolished in mice expressing a dominant negative Lck isoform (13) and in mice deficient of CD3ɛ and/or CD3ζ (14). In contrast to these reports, other experiments have yielded equivocal results. Inhibition of endogenous TCRβ rearrangements by a TCRβ transgene was only marginally impaired in mice deficient of Lck (15). In the absence of pre-Tα, inhibition of endogenous TCRβ rearrangements by TCRβ transgenes was unimpaired (16) or partially impaired (17), but allelic excusion among endogenous TCRβ genes was significantly compromised (18). From these inconsistencies, it appears that the role of pre-TCR/CD3 signaling in TCRβ allelic exclusion is so far incompletely understood.

In mice deficient for Lck and/or CD3ζ/η, we previously observed a pronounced reduction in the generation of CD25+ DN thymocytes harboring intracellular TCRβ polypeptide chains, owing to inefficient expression of productively rearranged TCRβ VDJ genes at the mRNA and protein levels (19). These findings predict that the failure to produce a TCRβ polypeptide chain after productive TCRβ VDJ rearrangement should result in an inability of the cell to assemble a pre-TCR, and in abrogated allelic exclusion. Here, we report that inhibition of endogenous TCRβ VDJ rearrangements by a functionally rearranged TCRβ transgene (P14, Vβ8.1-D-Jβ2.4; refs. 20 and 21) is severely impaired in Lck/CD3ζ/η-deficient mice. Moreover, in contrast to wt mice, P14 transgene expression is defective in CD25+ DN thymocytes of Lck/CD3ζ/η-deficient mice, similar to endogenous TCRβ genes. In Lck/CD3ζ/η-deficient mice, many CD25+ DN thymocytes that fail to express the TCRβ transgene express endogenous TCRβ polypeptide chains. Moreover, many DP thymocytes express endogenous TCRβ polypeptide chains together with the transgenic TCRβ, or more than one endogenous TCRβ chain. The results suggest that violation of allelic exclusion in mice with CD3 complex malfunctions may have two causes: inefficient expression of rearranged TCRβ genes and insufficient pre-TCR signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mice deficient of p56lck (22), mice deficient of CD3ζ/η (23), and mice carrying the P14 TCRβ transgene (Vβ8.1-D-Jβ2.4, strain 128.10) (20, 21) were bred in the specific pathogen-free animal facilities of the Max-Planck-Institut. Breedings of the p56lck and CD3ζ/η mutations were monitored by PCR analysis by using primers described in the original papers (22, 23). The P14β transgene (P14βtg) was detected by using as 5′ primer GGGTCTCTCCTGGTGTTT (from the H-2Kb promoter) and as 3′ primer TCTCCTTTCTCCGTGCTG (from the Vβ8.1 sequence).

mAb and Flow Cytometry.

Flow cytometry used the following mAbs, which were labeled with either FITC, phycoerythrin, or biotin, purchased from PharMingen: anti-CD4 (H129.19), anti-CD8 (53–6.7), anti-Vβ8 (F23.1), anti-Vβ11 (RR-3–15), anti-Vβ10 (B21.5), anti-TCRβ (H57–597), and anti-CD44 (IM7). Anti-CD25 (5A2) was purified and labeled with FITC in our own laboratory. Red-670 coupled to streptavidin was used for biotin-labeled antibodies. Thymocytes were preincubated with supernatant of anti-FcR mAb 2.4G2 before analysis. Three-color flow cytometry analysis used a FACScan (Beckton Dickinson). Intracellular staining was done on cells fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Saponin (Sigma) as described (10, 24). Sorting used a FACStar plus (Beckton Dickinson).

Analysis of TCRβ Gene Rearrangement by PCR.

TCRβ DJ and VDJ gene rearrangements were determined by semiquantitative PCR analyses essentially as described in ref. 19.

Analysis of Expression of the P14β Transgene by Reverse Transcription (RT)–PCR.

The P14β transgene was detected by RT-PCR by using primers described in ref. 14. Hypoxanthine phosphoryltransferase was used to estimate cDNA concentrations as described (19). Cycle conditions were 30 s at 94°C, 40 s at 69°C, and 60 s at 72°C.

RESULTS

The P14 TCRβ Transgene Fails to Rescue Thymocyte Development in Mice Deficient for CD3ζ and/or Lck.

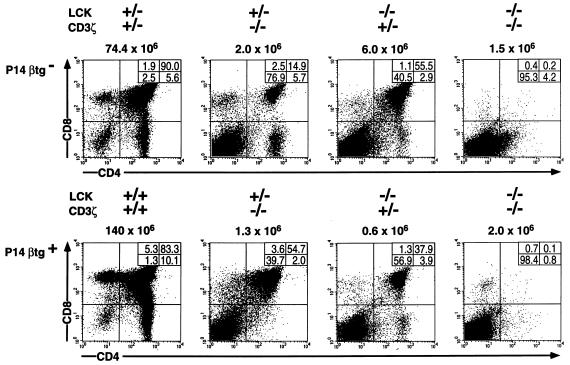

Mice bearing the P14 TCRβ transgene (P14βtg) were crossed with mice in which null mutations for Lck and for CD3ζ/η were segregating. Genotyping identified mice single-deficient (sd) for CD3ζ/η (ζ-sd) or Lck (Lck-sd), mice double-deficient (dd) for CD3ζ/η and Lck (ζ/Lck-dd), and mice bearing wt alleles for both genes, each with and without the P14βtg. Flow cytometry analyses of the thymocytes for CD4 and CD8 of representative individual mice from these breedings are shown in Fig. 1. As previously shown, ζ-sd and Lck-sd mice are able to generate DP cells and occasionally a few CD4 or CD8 single-positive cells, albeit in drastically reduced numbers (22, 23). In contrast, the generation of DP cells in ζ/Lck-dd mice is virtually abolished, consistent with a complete block in pre-TCR-dependent development (19). As expected from previous analyses of ζ-sd (14) and Lck-sd (15) mice, the P14βtg did not rescue thymocyte maturation in ζ/Lck-dd mice. The variations in total thymic cellularities, as well as the differences in the proportions of thymocyte subpopulations, were within the range of variation observed in each group of mice and were inconsistent with the presence or absence of the P14βtg.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of total thymocytes of adult wt, ζ-sd, Lck-sd, and ζ/Lck-dd mice, with and without the P14βtg, for CD4 and CD8. Absolute numbers of total thymocytes are given on top of each panel; percentages of cells in each subpopulation are given in the insets within each panel. Genotypes are given at the top.

Inhibition of Endogenous TCRβ Locus VDJ Rearrangement by the P14 TCRβ Transgene Is Abrogated in Mice Deficient for CD3ζ/η and/or Lck.

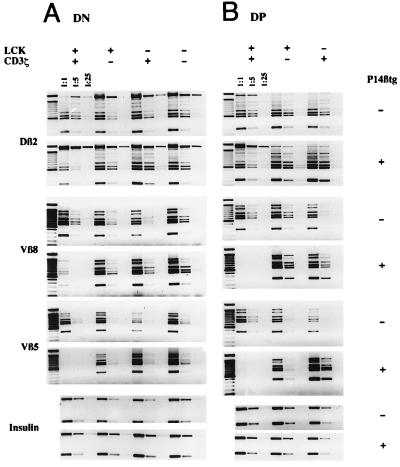

Fig. 2 A and B shows semiquantitative PCR analyses of TCRβ DJ and VDJ rearrangements in isolated DN cells of the four types of mice (Fig. 2A) and of DP cells of wt and sd mice (Fig. 2B), each with and without the P14βtg. In wt mice, VDJ but not DJ rearrangements were drastically reduced in the presence of the P14βtg. The analysis of DN cells suggests a suppression of endogenous rearrangements by the P14βtg of >85% for Vβ8 and >95% for Vβ5 whereas in DP cells suppression seemed virtually complete. In contrast to wt mice, DN cells of all three mutant mice displayed PCR signals for endogenous TCRβ VDJ rearrangements, which are indistinguishable in strength in the absence and presence of the P14βtg (Fig. 2A). Similarly, indistinguishable levels of endogenous rearrangements were seen in DP thymocytes of P14βtg− and P14βtg+ sd mice (Fig. 2B). Within the limits of this semiquantitative analysis, the data suggest that the P14βtg fails to inhibit endogenous TCRβ VDJ rearrangements in ζ-sd, Lck-sd, and ζ/Lck-dd mice.

Figure 2.

Semiquantitative PCR of sorted DN cells of adult wt, ζ-sd, Lck-sd, and ζ/Lck-dd mice (A) and of sorted DP cells of wt, ζ-sd, and Lck-sd mice (B) with and without the P14β transgene. DNA was adjusted to similar concentrations according to insulin PCR signals from 5-fold dilutions. After adjustment, DJ (Dβ2-Jβ2) and VDJ (Vβ5-D-Jβ2, Vβ8-D-Jβ2) PCR reactions were done in 5-fold dilutions as indicated. The Dβ2-Jβ2 and Vβ8-D-Jβ2 PCRs detect only the endogenous Vβ8 rearrangements, not the P14β transgene. In the DJ rearrangements, the top band represents the germline configuration. The six bands underneath and in the VDJ rearrangements represent the Jβ21–6 elements from top to bottom.

Inefficient Expression of the P14TCRβ Transgene in CD25+CD44− Thymocytes of Mice Deficient for CD3ζ/η and/or Lck.

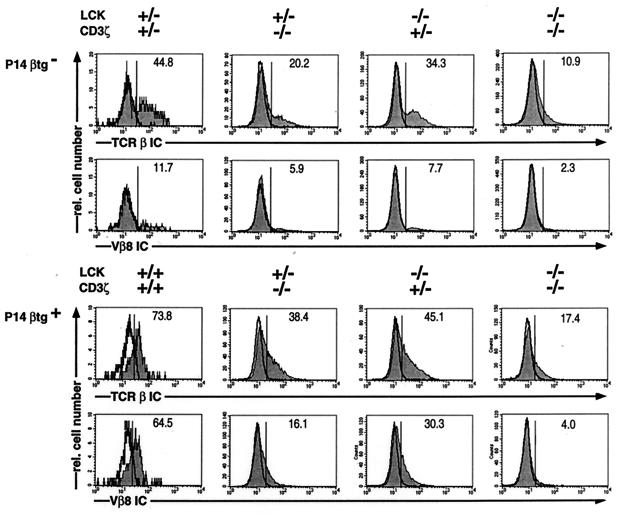

Allelic exclusion among endogenous TCRβ genes takes place at the CD25+CD44low/− stage of DN thymocyte development, and suppression of endogenous TCRβ VDJ rearrangements by a TCRβ transgene therefore requires expression of the transgene in this particular thymocyte subpopulation. Flow cytometric analyses of gated CD25+CD44− DN thymocytes for intracellular (IC) expression of total TCRβ chains as well as of transgenic and/or endogenous Vβ8 chains are shown in Fig. 3. In agreement with our previous results (19), the proportion of CD25+CD44− DN cells expressing TCRβ chains was diminished in P14βtg− sd mice and was strongly reduced in P14βtg− ζ/Lck-dd mice. Vβ8 staining of CD25+CD44− cells in P14βtg− mice labeled the expected proportions of about one-fourth of all TCRβ+ cells in wt and mutant mice, consistent with a proportional reduction in the expression of Vβ subfamilies. A comparison of CD25+CD44− DN thymocytes in P14βtg+ wt and mutant mice revealed no difference in absolute cell numbers (data not shown). However, staining for total TCRβ and for Vβ8 revealed pronounced differences in expression of the transgene between wt and mutant mice: The CD25+CD44− DN thymocytes of wt mice showed symmetrical staining profiles that are nearly identical for the pan-TCRβ mAb and for the mAb to Vβ8. The entire profiles were significantly shifted compared with the negative controls, suggesting that virtually all cells in the population express the P14βtg and few, if any, express endogenous TCRβ chains. In contrast, CD25+CD44− DN cells in P14βtg+ sd and dd mice showed skewed staining patterns with the pan-TCRβ mAb, the majority of the cells coinciding with the negative control. Less than half of the cells in sd mice and less than one-fourth of the cells in ζ/Lck-dd mice were positive for TCRβ chains. Together, the data in Fig. 3 suggest that the defective expression of endogenous TCRβ VDJ genes in thymocytes of mice with impaired CD3 complex signaling included the P14βtg. Moreover, the proportion of cells that stained with the pan-TCRβ mAb was significantly greater than that of cells staining with anti-Vβ8. The TCRβ+Vβ8− population varied between one-third and two-thirds of the TCRβ+ CD25+CD44− DN cells in individual P14βtg+ sd mice and was even greater in P14βtg+ ζ/Lck-dd mice. These results suggest that, in the mutant mice, a significant proportion of CD25+CD44− DN thymocytes that failed to express the Vβ8 transgene produced endogenous TCRβ polypeptide chains.

Figure 3.

Single parameter histiograms of intracellular TCRβ expression (TCRβIC) and intracellular Vβ8 expression (Vβ8IC), in gated DN CD25+CD44− thymocytes of wt, ζ-sd, Lck-sd, and ζ/Lck-dd mice, with and without the P14β transgene (shaded profiles). The mice were 4–5 weeks of age. Genotypes are given at the top. Relative numbers (percent) of TCRβIC+ cells and Vβ8IC+ cells are indicated in each frame. Negative controls for intracellular stainings used blocking with an excess of the same, unlabeled mAb (open profiles, bold).

Analysis of Dual Expression of Transgenic and Endogenous TCRβ Polypeptide Chains in DP Thymocytes of P14βtg+ Mice Deficient in CD3ζ/η or Lck.

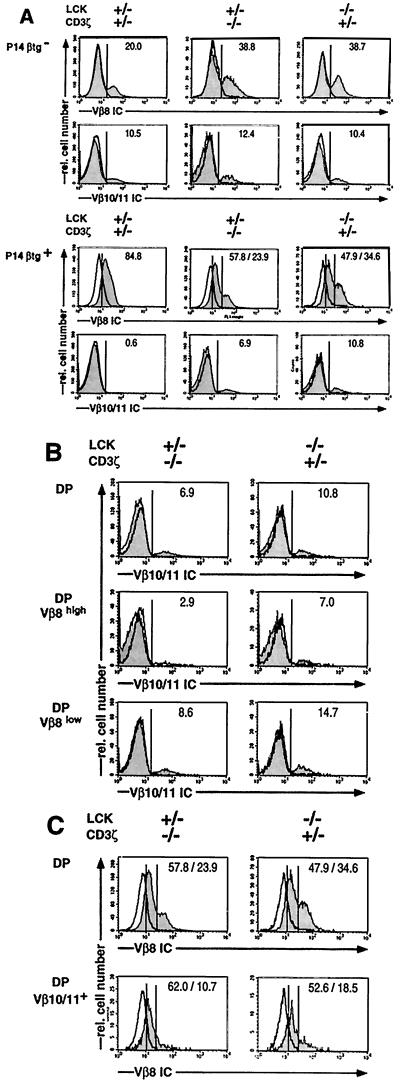

If the failure of the mutant mice to express the P14βtg in most CD25+CD44− DN thymocytes was the only factor that permitted the rearrangement and expression of endogenous TCRβ genes, the DP cells of these mice would be expected to consist of two separate populations: one expressing the P14βtg and the other expressing endogenous TCRβ genes. Conversely, if impaired pre-TCR signaling were an additional factor, DP thymocytes should be found that express both, endogenous TCRβ genes as well as the P14βtg. To address this question, DP cells of wt and sd mice were analyzed for TCRβ double-expressing cells by intracellular staining with two different TCRVβ reagents (Fig. 4). The TCRVβ single parameter histiograms are compiled in Fig. 4A. Anti-Vβ8 mAb stained an expected proportion of ≈20% of DP cells of P14βtg− wt mice whereas Vβ8 proportions in DP cells of P14βtg− sd mice were consistently found to be somewhat enhanced. As the second TCRβ reagent, we used a pool of mAb to Vβ10 and Vβ11. Although in combination the two mAb stained merely ≈10–12% of DP thymocytes in P14βtg− wt and sd mice, positive and negative cells could be distinguished unequivocally by a valley in the histiogram. Larger pools of anti-Vβ mAb did not permit this clear distinction.

Figure 4.

Three color flow cytometric analyses of thymocytes of adult wt, ζ-sd, and Lck-sd mice, with and without the P14β transgene, for CD4+CD8 and intracellular (IC) expression of TCRVβ elements (shaded profiles). In P14βtg+ mice, Vβ8 staining detects endogenous and/or transgenic TCRVβ elements. Vβ10/11 staining detects endogenous TCRVβ elements only. Negative controls for intracellular stainings used blocking with an excess of the same, unlabeled mAb (open profiles, bold). The mice were 4–5 weeks of age. Genotypes are given at the top. Percentages of positive cells are given in each frame. Percentages of Vβ8low and Vβ8high cells are indicated separately where appropriate. (A) Single parameter histiograms of Vβ8 and Vβ10/11 staining in DP cells. (B) Analysis of intracellular expression of Vβ10/11 polypeptide chains in total P14βtg+ ζ-sd or Lck-sd DP thymocytes and in P14βtg+ ζ-sd or Lck-sd DP thymocytes gated for low or high levels of Vβ8 polypeptide chains. To facilitate comparison, the Vβ10/11 profiles of total DP cells from A are repeated. (C) Analysis of intracellular expression of Vβ8 polypeptide chains in total P14βtg+ ζ-sd or Lck-sd DP thymocytes, and in P14βtg+ ζ-sd or Lck-sd DP thymocytes gated positive for Vβ10/11 polypeptide chains. To facilitate comparison, the Vβ8 profiles of total DP cells from A are repeated.

In P14βtg+ wt mice, virtually all DP cells were labeled by the Vβ8 mAb, suggesting that they expressed the P14βtg. The level of expression in most DP cells appeared somewhat lower than that of endogenous Vβ8 in P14βtg− wt mice. Nevertheless, Vβ10/11 staining in P14βtg+ wt DP cells was reduced to background levels, demonstrating efficient exclusion of endogenous TCRβ genes. In both P14βtg+ sd mice, DP thymocytes exhibited a biphasic distribution in the staining for Vβ8; in addition to the majority of cells showing low Vβ8 expression, a second population was seen with high Vβ8 levels similar to that in P14βtg− mice. We assume that the Vβ8low cells express transgenic Vβ8 whereas the Vβ8high cells express endogenous Vβ8 polypeptide chains. This is consistent with the maintenance of endogenous TCRβ expression in most DP cells of P14βtg+ sd mice as demonstrated by Vβ10/11 staining: Vβ10/11+ DP cells appeared at only a slightly lower proportion than in wt mice in P14βtg+ ζ-sd mice, and at a proportion equal to that of wt mice in P14βtg+ Lck-sd mice. Moreover, staining of DP cells of P14βtg+ sd mice with a pan-TCRβ mAb revealed a pattern indistinguishable from that of P14βtg− wt mice (data not shown).

The triple staining protocol used in the experiment in Fig. 4 allowed the direct assessment of DP thymocytes expressing more than one intracellular TCRβ chain. Fig. 4B compares Vβ10/11 expression in all DP cells with that in DP cells gated as Vβ8high and Vβ8low. The data show that Vβ10/11+ cells were enriched among Vβ8low cells whereas a reduction in Vβ10/11+ cells was seen among the Vβ8high populations. The reverse analysis is displayed in Fig. 4C, comparing Vβ8 expression in all DP cells of P14βtg+ sd mice with that in DP cells gated as Vβ10/11+. In agreement with the analysis in Fig. 4B, Vβ10/11+ DP cells of both P14βtg+ sd mice consisted mainly but not exclusively of cells with low Vβ8 expression. Together, the data in Fig. 4 B and C suggest that most DP thymocytes of P14βtg+ sd mice express endogenous TCRβ polypeptide chains in addition to the P14βtg. In addition, some of the DP cells of P14βtg+ sd mice may express more than one endogenous TCRβ gene.

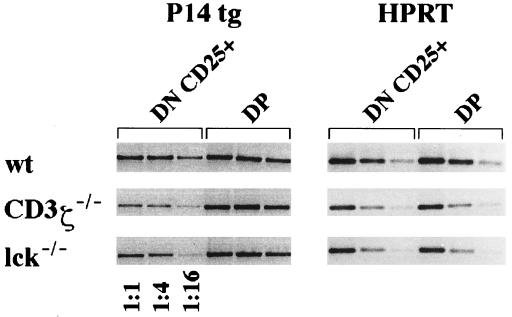

Analysis of the Expression of the P14βtg at the mRNA Level.

The anti-Vβ8 mAb used in these studies does not discriminate between the products of the P14βtg and of endogenous Vβ8 family members. To assess P14βtg expression specifically, we performed semiquantitative RT-PCRs with isolated thymocyte subsets from P14βtg+ wt and sd mice, using oligonucleotide primers that specifically detect the product of the P14βtg. As shown in Fig. 5, mRNA for the P14βtg was clearly detectable in the CD25+ DN and in the DP thymocyte subsets of P14βtg+ wt and sd mice, suggesting that at least a proportion of Vβ8+ cells in the mutant mice express the P14βtg. Moreover, the low P14βtg mRNA levels in DN cells of sd mice compared with DN cells of wt mice are consistent with the determination of TCRβ protein expression in Fig. 3. Transgene mRNA levels in DP cells did not obviously differ between wt and sd mice, consistent with our interpretation of the protein expression data in Fig. 4A.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR for expression of the P14βtg in isolated CD25+ DN and DP thymocytes of wt, ζ-sd, and Lck-sd mice. To sort DP cells, thymocytes were stained for CD4 and CD8 in different colors. To sort CD25+, DN cells thymocytes were stained for CD4+CD8+CD44 in one color against CD25 in a second color. Sorted populations were subjected to RT-PCR as described (19) by using hypoxanthine phosphoryltransferase as a quantitative marker.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that the initial expression of rearranged endogenous TCRβ VDJ genes in CD25+ DN thymocytes is impaired in mice deficient in CD3 complex signaling, at the level of TCRβ polypeptide chains and of TCRβ mRNA (19). The degree of impairment was proportional to the severity of CD3 malfunction, and the defect could be corrected by stimulation with anti-CD3ɛ mAb (19). As shown in the present paper, expression of the P14βtg in CD25+ DN thymocytes appears to be regulated in a way similar to endogenous TCRβ genes: First, we show that the degree of impairment in P14βtg expression is proportional to the severity of CD3 malfunction; second, P14βtg expression can be stimulated to wt levels with anti-CD3ɛ mAb (data not shown). It is important to consider the possibility that the paucity of TCRβ+ CD25+ DN cells is attributable to insufficient proliferation or impaired cellular survival instead of impaired P14βtg expression. The P14βtg is present in all cells, and we have no evidence for a subset of CD25+ DN cells incapable of expressing the P14βtg. Therefore, defective proliferation/longevity would result in a reduced number of total CD25+ DN cells, all of which would be positive for P14βtg polypeptide chains. However, we observed wt numbers of total CD25+ DN cells in the mutant mice, containing a reduced proportion of P14βtg+ cells. The present data therefore enforce our conclusion that the paucity of TCRβ positive CD25+ DN thymocytes is the consequence of a defect in TCRβ gene expression (19).

On the basis of the P14βtg construct, one would not have expected coregulation with endogenous TCRβ genes. The P14βtg consists of a coding sequence derived from a cDNA and heterologous control elements: i.e., the H-2Kb promoter, the IgH enhancer, and a 3′ untranslated region derived from the β-globin gene (20). However, the coregulation of the P14βtg together with endogenous TCRβ genes cannot be excluded on the basis of these heterologous control elements. Recently, evidence has accumulated that gene regulation in different hemopoetic lineages may be surprisingly similar and that transactivating factors may be shared among many different genes in these lineages (reviewed in ref. 25). At present, transcriptional and/or posttranscriptional mechanisms may be considered for the coregulation of the P14βtg and endogenous TCRβ genes. We do not think that translational or posttranslational regulation is involved because TCRβ mRNA and protein levels show no significant discrepancies (19).

Allelic exclusion of the TCRβ locus requires assembly of the pre-TCR and thus expression of a TCRβ VDJ gene at the protein level. The failure to express a TCRβ polypeptide chain after productive rearrangement of a TCRβ VDJ gene is thus expected to result in ongoing rearrangement and potentially the generation of a second productive VDJ gene in the same thymocyte. Inefficient expression of the P14βtg in CD25+ DN thymocytes of sd mice was shown on the protein and mRNA levels, in contrast to wt CD25+ DN thymocytes, the vast majority of which harbor the P14βtg polypeptide chain. In contrast to wt mice, the P14βtg does not prevent endogenous TCRβ rearrangements in the mutant mice. Moreover, endogenous TCRβ expression occurs to a large extent in CD25+ DN thymocytes that fail to express the P14βtg. These results confirm our prediction that the failure to express a rearranged TCRβ gene at the CD25+ DN stage permits the generation of additional productive TCRβ rearrangements.

Because of the requirements of TCRβ selection, the DP thymocytes generated in sd mice are expected to be selected from the CD25+ DN subset that expressed TCRβ chains, transgenic and/or endogenous. If the inefficient expression of the P14βtg in CD25+CD44− DN thymocytes was the only factor that permitted the rearrangement and expression of endogenous TCRβ genes, the DP cells of these mice would be expected to express either the P14βtg or endogenous TCRβ genes, but not both. Conversely, dual expression of endogenous TCRβ genes together with the P14βtg in DP thymocytes of sd mice would suggest that, in addition, endogenous rearrangements were permitted in CD25+ DN cells that expressed of the P14βtg. Dual TCRβ expression therefore would indicate impaired pre-TCR signaling as a second factor. Although our data suggest that virtually all DP cells of wt mice expressed the P14βtg, the heterogeneous Vβ8 staining of DP cells of sd mice did not reveal the exact proportions expressing the transgene. However, transgene mRNA was clearly demonstrated in the DP population, at levels similar to wt DP cells. Together, the data suggest that many DP cells of sd mice expressed the P14βtg together with an endogenous TCRβ chain. Violation of TCRβ allelic exclusion in mice with CD3 complex malfunction therefore may have had two causes: inefficient expression of TCRβ genes and inefficient pre-TCR signaling.

A subset of DP cells of sd mice showed higher staining for Vβ8, corresponding in size and expression level to that of nontransgenic sd mice. It was reasonable to assume that these represented endogenous Vβ8 polypeptide chains because the DP cells of sd mice expressed endogenous Vβ families at levels similar to that of wt mice. Dual expression among endogenous TCRβ genes in sd mice was suggested by the observation that DP populations gated for these putative endogenous Vβ8 chains contained significant proportions of Vβ10/11 positive cells, and vice versa. Although somewhat reduced, these proportions were nevertheless compatible with complete abrogation of endogenous TCRβ locus allelic exclusion.

Allelic exclusion by the P14βtg was studied in CD3ɛ deficient mice and was found to be fully defective (14). In contrast to our data, however, the authors reported efficient expression of the transgene in CD25+ thymocytes of these mice. Although these observations concern a different type of CD3 deficiency, they nevertheless represent a discrepancy that will have to be resolved. The same authors studied allelic exclusion in P14βtg+ ζ-sd mice with similar results as those presented here but did not address expression of the transgene (14). Allelic exclusion in Lck-sd mice was studied by using the HY TCRβ transgene (HYβtg) and was found to be maintained at 90% of the normal level (15). This discrepancy suggests that TCRβ transgenes differ in their sensitivity to perturbations in the signaling events that potentially account for impaired allelic exclusion. Such differences may very well relate to the degree by which a TCRβ transgene is subject to the endogenous control mechanisms that regulate TCRβ gene expression.

Incomplete expression of transgenic as well as endogenous TCRβ genes is associated with, and presumably a consequence of, defective CD3 signaling. The CD3 complexes responsible for TCRβ expression most likely correspond to clonotype-independent CD3 complexes, which appear on immature thymocytes before expression of a TCRβ chain and assembly of a pre-TCR. Because these data and our previous data suggest that clonotype-independent CD3 complexes appear to have an important function in pro-T cell differentiation, we suggest use of the term pro-TCR. So far, it is not clear in which way the pro-TCR generates developmental signals. Recent studies on the pre-TCR may suggest that surface assembly alone is sufficient to generate signals of low intensity that appear to suffice for early thymic differentiation (26). It is also of interest to consider which way the immature thymocyte distinguishes between signals from the pro-TCR and the pre-TCR, which translate into entirely different developmental responses, i.e., expression of TCRβ genes vs. TCRβ locus allelic exclusion, respectively. Further studies are needed to resolve these unanswered questions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. B. and M. Malissen and Dr. H. Pircher for mice, Dr. I. Haidl for critical reading of the manuscript, and Mr. H. Kohler and Ms. P. Wehrstedt for able technical assistance. This paper was written while K.E. was a Scholar-in-Residence at the Fogarty International Center for Advanced Study in the Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

ABBREVIATIONS

- sd

single-deficient

- dd

double-deficient

- wt

wild-type

- tg

transgene

- Lck

p56lck

- DP

double-positive

- DN

double-negative

- TCR

T cell receptor

- RT

reverse transcription

- IC

intracellular

- V

variable

- D

diversity

- J

joining

References

- 1.Levelt C N, Eichmann K. Immunity. 1995;3:667–672. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehling H J, von Boehmer H. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kisielow P, von Boehmer H. Adv Immunol. 1995;58:87–209. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robey E, Fowlkes B J. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zunicka-Pflücker J L, Lenardo M J. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Ardouin L, Gillet A, Lin S Y, Magnan A, Malissen B, Malissen M. Immunol Rev. 1995;148:171–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shortman K, Wu L. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:29–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malissen M, Tracy J, Janvin-Marche E, Cazenave P A, Scolley R, Malissen B. Immunol Today. 1992;13:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uematsu Y, Ryser S, Dembic S Z, Borgulya P, Krimpenfort P, Berns A, von Boehmer H, Steinmetz M. Cell. 1988;52:831–841. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levelt C N, Ehrfeld A, Eichmann K. J Exp Med. 1993;177:707–716. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levelt C N, Wang B, Ehrfeld A, Terhorst C, Eichmann K. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1257–1261. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson S J, Abraham K M, Nakayama T, Singer A, Perlmutter R M. EMBO J. 1992;11:4877–4886. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson S J, Levin S D, Perlmutter R M. Nature (London) 1993;365:552–554. doi: 10.1038/365552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ardouin L, Ismaili J, Malissen B, Malissen M. J Exp Med. 1998;187:105–116. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace V A, Kawai K, Levelt C N, Kishihara K, Molina T, Timms E, Pircher H, Penninger J, Ohashi P, Eichmann K, et al. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1312–1318. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Davidson L, Alt F W, Baltimore D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2169–2173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krotkova A, von Boehmer H, Fehling H J. J Exp Med. 1997;186:767–775. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aifantis I, Buer J, von Boehmer H, Azogui O. Immunity. 1998;7:601–607. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Würch A, Biro J, Potocnik A J, Falk I, Mossmann H, Eichmann K. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pircher H P, Mak T W, Lang R, Ballhausen W, Ruedi E, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M, Bürki K. EMBO J. 1989;8:719–727. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pircher H P, Bürki K, Lang R, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Nature (London) 1989;342:559–561. doi: 10.1038/342559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molina T J, Kishihara K, Siderovski D P, Van Ewijk W, Narendran A, Timms E, Wakeham A, Paige C J, Hartmann K U, Veillette A, et al. Nature (London) 1992;357:161–164. doi: 10.1038/357161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malissen M, Gillet A, Rocha B, Trucy J, Vivier E, Boyer C, Kontgen F, Brun N, Mazza G, Spanopoulou E, et al. EMBO J. 1993;12:4347–4355. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levelt C N, Carsetti R, Eichmann K. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1867–1875. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glimcher L H, Singh H. Cell. 1999;96:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irving B A, Alt F W, Killeen N. Science. 1998;280:905–909. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]