Abstract

CandidaDB (http://genodb.pasteur.fr/CandidaDB) was established in 2002 to provide the first genomic database for the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. The availability of an increasing number of fully or partially completed genome sequences of related fungal species has opened the path for comparative genomics and prompted us to migrate CandidaDB into a multi-genome database. The new version of CandidaDB houses the latest versions of the genomes of C. albicans strains SC5314 and WO-1 along with six genome sequences from species closely related to C. albicans that all belong to the CTG clade of Saccharomycotina—Candida tropicalis, Candida (Clavispora) lusitaniae, Candida (Pichia) guillermondii, Lodderomyces elongisporus, Debaryomyces hansenii, Pichia stipitis—and the reference Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. CandidaDB includes sequences coding for 54 170 proteins with annotations collected from other databases, enriched with illustrations of structural features and functional domains and data of comparative analyses. In order to take advantage of the integration of multiple genomes in a unique database, new tools using pre-calculated or user-defined comparisons have been implemented that allow rapid access to comparative analysis at the genomic scale.

INTRODUCTION

Candida species are the most important opportunistic fungal pathogens of humans responsible for superficial and systemic infections (1). Among these species, Candida albicans is responsible for the majority of infections, but other species are becoming increasingly common (1). Because of its predominance, C. albicans has been the focus of genomic and molecular studies over the last 20 years, becoming a model organism for other pathogenic Candida species and fungal pathogens. The C. albicans genome was made publicly available by the Stanford Genome Technology Center at the end of the 1990s and different assemblies and annotations have been released since (2–4). This has been accompanied by the implementation of two main genomic databases: CandidaDB (5) and the Candida Genome Database (6,7).

As infections due to non-albicans Candida in hospitals have increased (8), research on these emerging species has recently developed. Genome sequencing projects for these species, as well as related non-pathogenic yeast species, have been completed or are nearing completion (4,9–12). The availability of numerous related genomes paves the way for comparative genomic approaches that have already contributed to our understanding of the evolutionary processes that underlie speciation in the Sachharomycotina subphylum (10,13–15). Applied to closely-related pathogenic and non-pathogenic yeast species, comparative genomics should provide insights in virulence processes.

To date, most yeast genomes are available at different databases and there is no resource that enables online comparative analysis. The current aim of the CandidaDB database is to provide such a comparative resource for species of the CTG clade of the subphylum Saccharomycotina that is characterized by the translation of the CUG codon into serine instead of leucine. The CTG clade includes C. albicans and several of the most important human pathogenic fungi (16–18). CandidaDB provides genome sequences of four pathogenic [C. albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida (Clavispora) lusitaniae, Candida (Pichia) guillermondii] and three non-pathogenic (Lodderomyces elongisporus, Debaryomyces hansenii, Pichia stipitis) species belonging to the CTG clade (Table 1). It also provides the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence as a reference (19). CandidaDB includes sequences coding for 54 170 proteins with annotations collected from other databases. It has been enriched with illustrations of structural features and functional domains and tools for sequence comparisons and analysis. Moreover, new tools for comparative genomics have been implemented in order to take advantage of the integration of multiple genomes in a unique database. Importantly, pre-calculated comparisons provide rapid access to comparative analysis at the protein and genomic scale.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the nine genomes available in the current release of CandidaDB

| Species | Strain | Number of proteins | Number of chromosomes and/or supercontigs | Status and release date | Sequencing center/Database repository | Database links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans | SC5314 | 6098 | 8 | Draft assembly 13 September 2006 | CGD | http://www.candidagenome.org/ |

| Candida albicans | WO1 | 6159 | 16 | Draft assembly 15 March 2006 | Broad Institute | http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/candida_albicans/ |

| Candida guilliermondii | ATCC6260 | 5920 | 9 | Draft assembly 15 March 2006 | Broad Institute | http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/candida_guilliermondii/ |

| Candida tropicalis | MYA-3404 | 6258 | 23 | Draft assembly 12 June 2006 | Broad Institute | http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/candida_tropicalis/ |

| Candida lusitaniae | ATCC42720 | 5941 | 9 | Draft assembly 25 January. 2006 | Broad Institute | http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/candida_lusitaniae/ |

| Debaryomyces hansenii | CBS767 | 6318 | 7 | Complete 3 July 2004 | Génolevures | http://cbi.labri.fr/Genolevures/elt/DEHA |

| Pichia stipitis | CBS 6054 | 5816 | 9 | Complete 17 April 2007 | JGI | http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Picst3/Picst3.home.html |

| Lodderomyces elongisporus | NRLL YB-4239 | 5802 | 27 | Draft assembly 12 June 2006 | Broad Institute | http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/lodderomyces_elongisporus/ |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | S288C | 5858 | 16 | Complete 27 March 2007 | SGD | http://www.yeastgenome.org/ |

| Total | 9 | 54 170 | 124 |

SOURCE DATA AND COMPATIBILITY WITH OTHER DATABASES

Eight publicly available genome sequences of seven closely related species belonging to the CTG clade are included in the new release of CandidaDB: the genomes of C. albicans strains SC5314 (2) and WO1 (20); three genomes of other pathogenic species, C. tropicalis strain MYA-3404 (21), C. lusitaniae strain ATCC42720 (22) and C. guilliermondii strain ATCC6260 (23); and the genomes of three non-pathogenic species, L. elongisporus strain NRLL YB-4239 (24), an ascososporogenous species, D. hansenii strain CBS767 (10), a halotolerant yeast found in fish and salted dairy products that have a role in agro-food processes and Pichia stipitis strain CBS6054 (12), a xylose fermenting yeast. The new release of CandidaDB also includes the S. cerevisiae strain S288C genome (19) in order to take advantage of the high level of annotation provided for this species that is not part of the CTG clade but is part of the Saccharomycotina subphylum (17). These genome sequences and associated annotations were obtained from the sources indicated in Table 1 that summarizes the general information for the nine genomes available in the current version of CandidaDB.

The new version of CandidaDB uses Assembly 20 of the genome sequence of C. albicans strain SC5314 genome available at the Candida Genome Database (CGD) (4,7). While previous releases of CandidaDB used annotations contributed by the Galar Fungail consortium (5), CandidaDB now uses sequences, descriptions, accession numbers and annotations available at CGD which is the reference depository site for C. albicans. This allows homogenization of the nomenclature for this organism and will simplify literature curation. Accession numbers of previous CandidaDB releases are still available as synonyms.

The genomes of P. stipitis, D. hansenii and S. cerevisiae available through CandidaDB are considered completed and have been published (10,12,19), while the other genomes are draft assemblies, close to completion and with a low number of contigs. CandidaDB aims to follow the usual accession number for Open Reading Frames (ORFs) provided by the institutions which performed the sequences, for better clarity, inter-database relations and faster update procedures.

IMPLEMENTATION

CandidaDB is based on the general data frame called GenoList (25). GenoList is an integrated environment for multiple genomes based on a relational database run through a web user interface that provides comparative genomic and proteomic tools in complement to the gene descriptions. Structure and design are detailed in the accompanying paper (25). GenoList has been originally developed as a multigenome database for comparative analysis of bacterial genomes (25) and has been adapted to eukaryotes in order to manage the CandidaDB database.

When connecting to CandidaDB, users are prompted to register and provide a login and password. Although this is optional and no tracking of the registered users is performed, it allows users to specify parameters for CandidaDB usage (see subsequently) and maintain these parameters upon return to the database. Upon registered or unregistered login, users have access to a web interface that is composed of a main window allowing different forms of queries and analysis at the gene, genome and multi-genome scale. Results of the queries are presented in the main window as gene lists. Genes can be accessed through a gene–specific window providing reports, a dynamic map of the genomic environment, pre-computed data of comparative proteomic analysis and tools for sequence analysis and downloads as described subsequently.

An important component of CandidaDB is the possibility for users to select those genomes that they wish to query from the list of all available genomes. Users can define a favourite genome, a query list of genomes and a comparative list of genomes. Through these selections, CandidaDB can be made a database focused on a favourite organism and provide comparative data for genomes of the comparative list only. The query list is used in search and comparative tools as described subsequently. Several comparative and query lists can be specified and remain accessible to registered users upon return to the database.

ANALYSIS AND VISUALIZATION TOOLS

The migration of CandidaDB to the GenoList multi-genome environment combined with the integration of nine genomes expands the possibilities for genome and proteome analysis and allows access to comparative genomics. Search options are identical to those available in the previous version of CandidaDB: the left panel of the main window allows the search by gene names and synonyms, accession numbers, text and location in the set of genomes defined by the user (favourite organism, query or comparative lists) or in all genomes present in CandidaDB. BLAST search (26) and pattern search tools are also accessible from the left panel as well as two new tools for comparative genomic analysis, FindTarget and DiffTool.

FindTarget (27) allows the user to identify genes from a given genome (‘Query genome’, the user-defined favourite organism) that, based on tuneable criteria (percentage of identity, E-value, etc.), are specifically present in a set of genomes (‘Reference genomes’, by default the user-defined query list) and, optionally, absent in another set of genomes (‘Exclusion genomes’, by default the user-defined comparative list). The algorithm makes use of pre-computed BLASTP best hits obtained upon systematic comparisons of all protein versus all proteins available in CandidaDB.

DiffTool (28) allows the identification of protein families whose components are shared by a set of organisms (‘Reference genomes’) as compared to another set of organisms (‘Exclusion genomes’). Protein families have been pre-computed in CandidaDB using data of systematic BLASTP comparisons of every protein versus all proteins. Several family sets are available according to the criteria used in the clustering procedure (e.g. proteins that share at least 40, 50 or 60% sequence similarity over 80% of the protein length). Results are provided in the main window as a list of annotated protein families, each linked to the list of included proteins and a ClustalW multiple alignment (29).

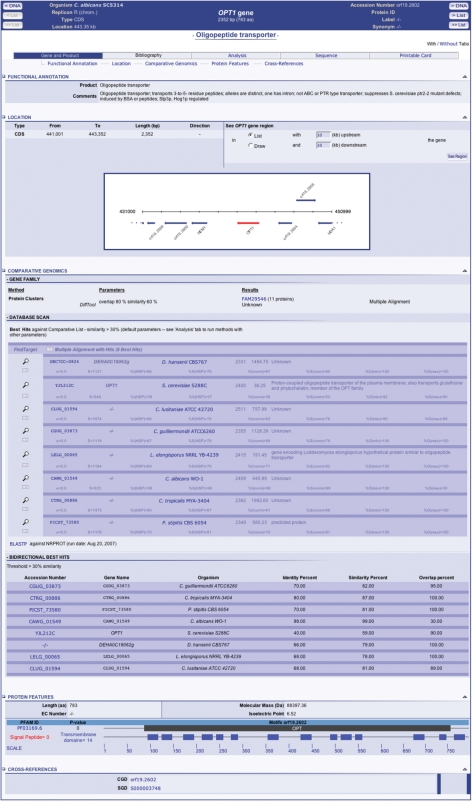

Results of the different searches are displayed in the main window as gene lists, each gene being linked to a specific page that provides description, annotation and a graphical view of the genomic environment of the gene (Figure 1). Pre-computed results from comparative analysis for protein families (DiffTool) and best hits (FindTarget) and a regularly updated BLASTP comparison to the non-redundant protein databank (30) are systematically available (Figure 1). ClustalW pairwise or multiple alignments with best hits found in the genomes of the comparative list are provided. A list of bi-directional best hits (BDBH) is also provided. Additional protein features are displayed graphically showing signal peptide and membrane-spanning domains predicted using the Phobius software (31) and PFAM domains (32) (Figure 1). Direct links to relevant databases are listed in the cross-references panel (Figure 1). Tuneable, not pre-defined, search tools (BLAST, DiffTool, FindTarget) and sequence retrieval tools are accessible in the Analysis and Sequence tabs of this gene window, respectively.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of a gene window for the C. albicans OPT1 gene. The gene window displays annotation data, a dynamic map of the genomic region surrounding the OPT1 gene, access to a protein cluster including the Opt1 protein, a list of best hits identified in genomes of the comparative list with links to pairwise and multiple ClustalW alignments, a list of bi-directional best hits in other genomes available in CandidaDB, a graphical representation of predicted signal peptide, transmembrane domains and PFAM domains, and links to relevant pages in other databases. Other tabs in the gene window allow access to dynamic analysis tools and tools for sequence retrieval.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

The integration in a single database of a large number of genome sequences from related yeast species provides an unprecedented tool for comparative genomics of yeasts. The new version of CandidaDB aims to provide information complementary to that available at the Candida Genome Database by implementing comparative genomic tools and by providing data on functionally-relevant protein domains which were not directly available yet. Access to these data is facilitated by the use of pre-computed multi-genome analysis that are normally CPU-intensive. Yet CandidaDB provides the ability to perform similar queries with user-defined parameters avoiding the limitations of these static results. The user-defined lists of genomes allow the user to limit searches and results to selected organisms, an option that will be increasingly useful when a larger number of genomes becomes available through the database.

CandidaDB is a convenient entry point for the community working on other Candida species than C. albicans since any Candida genome can be used as the favourite genome. It should be helpful for those who are working with genomes that are still undergoing annotation. In this regard, the comparative tools available in CandidaDB can be used to refine some of the gene models provided by sequencing centers. They can also be used to focus functional genomic studies that should eventually identify gain or loss of functions that underlie the differences in pathogenicity, virulence and morphogenesis observed between the different species of the CTG clade of Saccharomycotina.

Other genomes of species within the CTG clade, e.g. C. parapsilosis and C. dubliniensis, have been recently sequenced and are undergoing annotation. The same is true for species of the Saccharomycotina that do not belong to the CTG clade. Our aim is to incorporate these genomes into CandidaDB as they become publicly available, to update sequences and annotations in a regular manner and to provide new tools for comparative and structural analysis. In particular, the incorporation in CandidaDB of a synteny visualisation tool will greatly help in the interpretation of the comparative data outputs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Louis Jones for help in making the database publicly available. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Institut Pasteur.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive Candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones T, Federspiel NA, Chibana H, Dungan J, Kalman S, Magee BB, Newport G, Thorstenson YR, Agabian N, et al. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. PNAS. 2004;101:7329–7334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401648101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun BR, van Het Hoog M, d’Enfert C, Martchenko M, Dungan J, Kuo A, Inglis DO, Uhl MA, Hogues H, et al. A human-curated annotation of the Candida albicans genome. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:36–57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van het Hoog M, Rast T, Martchenko M, Grindle S, Dignard D, Hogues H, Cuomo C, Berriman M, Scherer S, et al. Assembly of the Candida albicans genome into sixteen supercontigs aligned on the eight chromosomes. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R52. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.d’Enfert C, Goyard S, Rodriguez-Arnaveilhe S, Frangeul L, Jones L, Tekaia F, Bader O, Albrecht A, Castillo L, et al. CandidaDB: a genome database for Candida albicans pathogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D353–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnaud MB, Costanzo MC, Skrzypek MS, Binkley G, Lane C, Miyasato SR, Sherlock G. The Candida Genome Database (CGD), a community resource for Candida albicans gene and protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D358–D363. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnaud MB, Costanzo MC, Skrzypek MS, Shah P, Binkley G, Lane C, Miyasato SR, Sherlock G. Sequence resources at the Candida Genome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D452–456. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krcmery V, Barnes AJ. Non-albicans Candida spp. causing fungaemia: pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. J. Hospital Infection. 2002;50:243–260. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galagan JE, Henn MR, Ma L.-J, Cuomo CA, Birren B. Genomics of the fungal kingdom: Insights into eukaryotic biology. Genome Res. 2005;15:1620–1631. doi: 10.1101/gr.3767105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dujon B, Sherman D, Fischer G, Durrens P, Casaregola S, Lafontaine I, de Montigny J, Marck C, et al. Genome evolution in yeasts. 2004;430:35–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logue ME, Wong S, Wolfe KH, Butler G. A genome sequence survey shows that the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis has a defective MTLa1 allele at its mating type locus. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:1009–1017. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.6.1009-1017.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeffries TW, Grigoriev IV, Grimwood J, Laplaza JM, Aerts A, Salamov A, Schmutz J, Lindquist E, Dehal P, et al. Genome sequence of the lignocellulose-bioconverting and xylose-fermenting yeast Pichia stipitis. 2007;25:319–326. doi: 10.1038/nbt1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellis M, Patterson N, Endrizzi M, Birren B, Lander ES. Sequencing and comparison of yeast species to identify genes and regulatory elements. 2003;423:241–254. doi: 10.1038/nature01644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer G, Rocha EPC, Brunet F., d.r, Vergassola M, Dujon B. Highly Variable Rates of Genome Rearrangements between Hemiascomycetous Yeast Lineages. PLoS Genetics. 2006;2:e32. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romov P, Li F, Lipke P, Epstein S, Qiu W.-G. Comparative Genomics Reveals Long, Evolutionarily Conserved, Low-Complexity Islands in Yeast Proteins. J. Mol. Evol. 2006;63:415–425. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos MA, Tuite MF. The CUG codon is decoded in vivo as serine and not leucine in Candida albicans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1481–1486. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick DA, Logue ME, Stajich JE, Butler G. A fungal phylogeny based on 42 complete genomes derived from supertree and combined gene analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diezmann S, Cox CJ, Schonian G, Vilgalys RJ, Mitchell TG. Phylogeny and evolution of medical species of Candida and related taxa: a multigenic analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:5624–5635. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5624-5635.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, et al. Life with 6000 Genes. Science. 1996;274:546–567. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slutsky B, Buffo J, Soll D. High-frequency switching of colony morphology in Candida albicans. Science. 1985;230:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.3901258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joly S, Pujol C, Schroppel K, Soll D. Development of two species-specific fingerprinting probes for broad computer-assisted epidemiological studies of Candida tropicalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:3063–3071. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3063-3071.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pappagianis D, Collins MS, Hector R, Remington J. Development of resistance to amphotericin B in Candida lusitaniae infecting a human. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:123–126. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thanos M, Schonian G, Meyer W, Schweynoch C, Graser Y, Mitchell T, Presber W, Tietz H. Rapid identification of Candida species by DNA fingerprinting with PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:615–621. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.615-621.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Walt JP. Lodderomyces, a new genus of the Saccharomycetaceae. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1966;32:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02097439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechat P, Hummel L, Rousseau S, Moszer I. GenoList: an integrated environment for comparative analysis of microbial genomes. Nucl Acids Res. 2008;36:D469–D474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chetouani F, Glaser P, Kunst F. FindTarget: software for subtractive genome analysis. Microbiology. 2001;147:2643–2649. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-10-2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chetouani F, Glaser P, Kunst F. DiffTool: building, visualizing and querying protein clusters. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1143–1144. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wheeler DL, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, DiCuccio M, Edgar R, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:D5–D12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. An HMM posterior decoder for sequence feature prediction that includes homology information. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i251–i257. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]