Abstract

CD8+ T lymphocytes that specifically recognize tumor cells can be isolated and expanded ex vivo. While the lytic properties of these cells have been well described, their fate upon encounter with cognate tumor is not known. We performed reverse 51Cr release assays in which the lymphocyte effectors rather than the tumor cell targets were radioactively labeled. We found that melanoma tumor cells caused the apoptotic death of tumor-specific T cells only upon specific MHC class I-restricted recognition. This death was entirely blockable by the addition of an Ab directed against the Fas death receptor (APO-1, CD95). Contrary to the prevailing view that tumor cells cause the death of anti-tumor T cells by expressing Fas ligand (FasL), our data suggested that FasL was instead expressed by T lymphocytes upon activation. While the tumor cells did not express FasL by any measure (including RT-PCR), functional FasL (as well as FasL mRNA) was consistently found on activated anti-tumor T cells. We could successfully block the activation-induced cell death with z-VAD-fmk, a tripeptide inhibitor of IL-1β-converting enzyme homologues, or with anti-Fas mAbs. Most importantly, these interventions did not inhibit T cell recognition as measured by IFN-γ release, nor did they adversely affect the specific lysis of tumor cell targets. These results imply that Fas-mediated activation-induced cell death could be a limiting factor in the in vivo efficacy of adoptive transfer of class I-restricted CD8+ T cells and provide a means of potentially enhancing their growth in vitro as well as their function in vivo.

The CD8+ T lymphocyte has been shown to mediate the regression of tumors in many tumor models. In patients suffering from metastatic melanoma, the adoptive transfer of T cell lines established from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in combination with the systemic administration with IL-2 has been associated with a response rate of 30–40% (partial and complete responses) (1). Most of the responses (over those seen with IL-2 therapy alone) have been partial and, while biologically significant, were often transient (2). The in vivo efficacy has been correlated with the ability of these T cells to lyse tumor targets in vitro (1), the specific recognition of the melanoma-associated Ag gp100 (3), and trafficking to the tumor site (4). Recognition by these T cells has been extensively analyzed and has served as a basis for the molecular elucidation of the tumor-associated Ags.

While it is clear that T cells kill tumor cells, the effect of the tumor-lymphocyte interaction on the viability of the lymphocytes themselves has not been characterized. The outcome of recurrent interaction with antigenic tumor cells can be expected to lead to either proliferation or deletion by activation-induced cell death (AICD),2 and the elucidation of this outcome is relevant to the efforts to achieve efficacious immunotherapy. In light of the recent attention given to the possibility that Fas ligand (FasL, CD95)-expressing melanoma cells actively delete Fas+ lymphocytes infiltrating the tumor bed (2, 5), we sought to analyze both the susceptibility of tumor reactive T cell lines grown in vitro to FasL-induced cell death as well as their fate upon interaction with cognate and noncognate melanoma tumor cells in vitro. Our data support an important role for Fas-FasL interaction in the deletion of activated tumor-reactive T cells, but by a mechanism different from the one previously proposed.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

T cell lines that had been previously isolated from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (6) were thawed and maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10 nM glutamine, 250 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 10% human AB serum (Gemini, Casabas, CA), and 6000 IU IL-2 (Tecin, Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% carbon dioxide. These cell lines were ≥75% CD8+, except for line 888, which was 72% CD4+ and 26% CD8+. Tumor cell lines that had previously been established in our laboratory were maintained in similar medium, except for the use of 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Biofluids). For CTL lines 888, 907, 1143, 1359, and 1495, autologous tumor lines were available and used for recognition experiments. 624 is an HLA-A2+ melanoma line; 624.38 and 624.28 are HLA-A2high and HLA-A2− clones, respectively. These lines have previously been shown in our laboratory to be recognized by CTL 1143 and CTL 1520 in an HLA-A2-restricted manner. L1210 and the Fas-transfected clone L1210Fas (7) were a kind gift of Dr. P. A. Henkart (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Abs and chemical reagents

Anti-Fas Abs Ab-2 and Ab-3 (a kind gift of Calbiochem, Cambridge, MA) were used for flow cytometry analysis. Anti-Fas Abs FM-3 (a kind gift of Dr. David Lynch, Immunex, Seattle, WA) and SM1/23 (Alexis, San Diego, CA) were used as blocking Abs at the indicated concentrations. Anti-TNF-α (Endogen, Woburn, MA) was used where indicated. Caspase inhibitors Z-Val-Ala-Asp-CH2F (z-VAD) and BOC-Asp-CH2F (BAF) (Enzyme Systems, Dublin, CA) were reconstituted according to manufacturer's recommendation and used at a final concentration of 20 μM unless otherwise indicated. Soluble human recombinant FasL and enhancer protein were used as recommended by the manufacturer (Alexis).

Cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretion assays

Cellular viability assays based on mitochondrial enzymatic activity were performed with the WST-1 assay (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, 105 cells per well were plated in flat-bottom 96-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) in triplicate wells per condition. For each cell line, duplicate wells with varying numbers of cells were simultaneously plated. The enzymatic assay was performed after 24 h; a standard regression curve was plotted for each line, and the percentage of viable cells was calculated. For 51Cr release assays, target cells were preincubated in 200 μCi 51Cr (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) for 90 min, washed, and plated at 5 × 103 to 5 × 104 per well in triplicate, and various numbers of effectors were added for 16 h at 37°C, following which supernatants were collected and counted on a γ-counter. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as (sample counts – spontaneous counts)/(maximal counts – spontaneous counts) × 100%. Maximal release was obtained by incubating target cells with 2% SDS, and negative values were zeroed. For IFN-γ release assays, 5 × 104 effectors were cocultured with 105 target cells per well in duplicate for 24 h, after which the supernatants were analyzed by IFN-γ ELISA (Endogen). IFN-γ levels of ≥100 pg/ml and at least twice as high as controls were considered positive.

Results

T cell death is dependent upon recognition of tumor targets

To study the possible induction of tumor-specific CD8+ T cell apoptosis by tumor cells, the CD8+ T cell line 1143 was coincubated at different E:T ratios with 624.38 (HLA-A2high) and 624.28 (HLA-A2−) melanoma clones. As seen in Fig. 1a, up to 60% of CD8+ T cells were induced to undergo apoptosis, but only by the tumor cells that they could recognize (as shown by concurrent IFN-γ levels, Fig. 1b), indicating a requirement for CD8+ T cell activation for apoptosis to occur. Furthermore, apoptosis was increased as the relative proportion of lymphocytes to tumor cells increased, suggesting that interlymphocyte contact (as opposed to lymphocyte-tumor cell contact) was mediating apoptosis and was in contrast to the effect of different E:T ratios on the secreted IFN-γ (similar results were obtained with T cell line 1520, data not shown). An additional four CD8+ T cell lines, assayed against autologous or non-HLA-matched tumors, showed the same phenomena: apoptosis of the tumor-specific CD8+ T cells depended on recognition of the tumor cells (Fig. 2). The percentage of cells susceptible to lysis varied between 10 and 50%, probably as a reflection of the relative proportion of actual tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in the line and a lower E:T ratio (1:1). These results cannot be readily explained by expression of FasL by the tumor cells, as this would result in indiscriminate killing. However, they could be explained by AICD of the lymphocytes, i.e., the induction of FasL on the lymphocytes. Thus, we turned to examining the expression of Fas on these CD8+ T cells lines and their susceptibility to FasL.

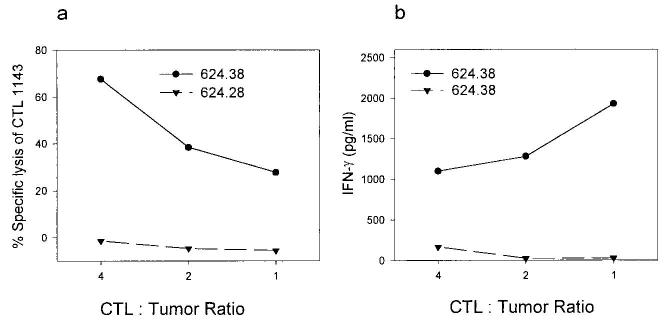

FIGURE 1.

Tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells are induced to die when they specifically recognize tumor targets. T cell line 1143 was coincubated at the E:T ratios shown with the HLA-A2+ melanoma clone 624.38 or the HLA-A2− subclone 624.28 for 20 h, keeping the number of CD8+ T cells constant. a, T cells were prelabeled with 51Cr, and supernatants were harvested to determine specific cytotoxicity of T cells (results are mean of triplicate). b, Supernatants from identical wells containing nonlabeled T cells were assayed for IFN-γ release. Data are representative of at least two separate experiments, and similar data were obtained for a second lymphocyte culture (line 1520).

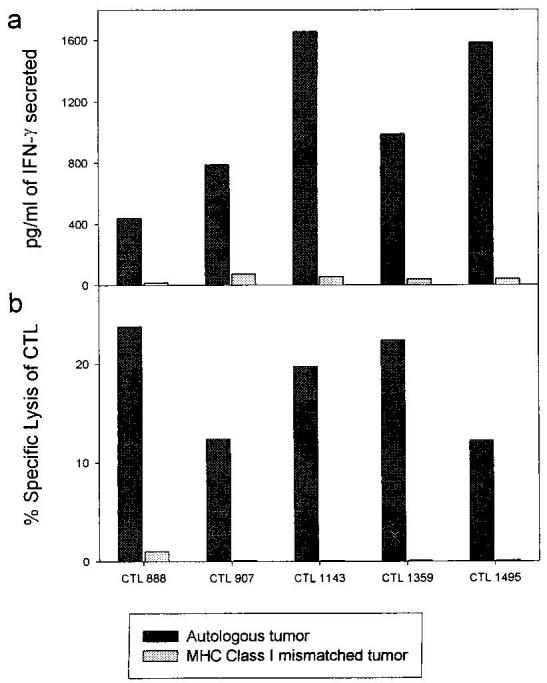

FIGURE 2.

Lysis of CD8+ T cells is correlated by tumor targets correlates with tumor-specificity. 51Cr-labeled and unlabeled (for IFN-γ release) CD8+ T cells and tumor targets (either autologous or allogeneic mismatched for MHC class I) were coincubated for 20–24 h, after which IFN-γ levels (a) and 51Cr release (b) were determined in the supernatants. CD8+ T cells lines that had previously been found to display class I-restricted cytotoxicity were used; their numbers are given on the bottom. Mismatched lines were Mel 1143 (for 888), 1338 (for 907, 1143, and 1359), and 1359 (for 1495). Assays were reproduced twice with similar results.

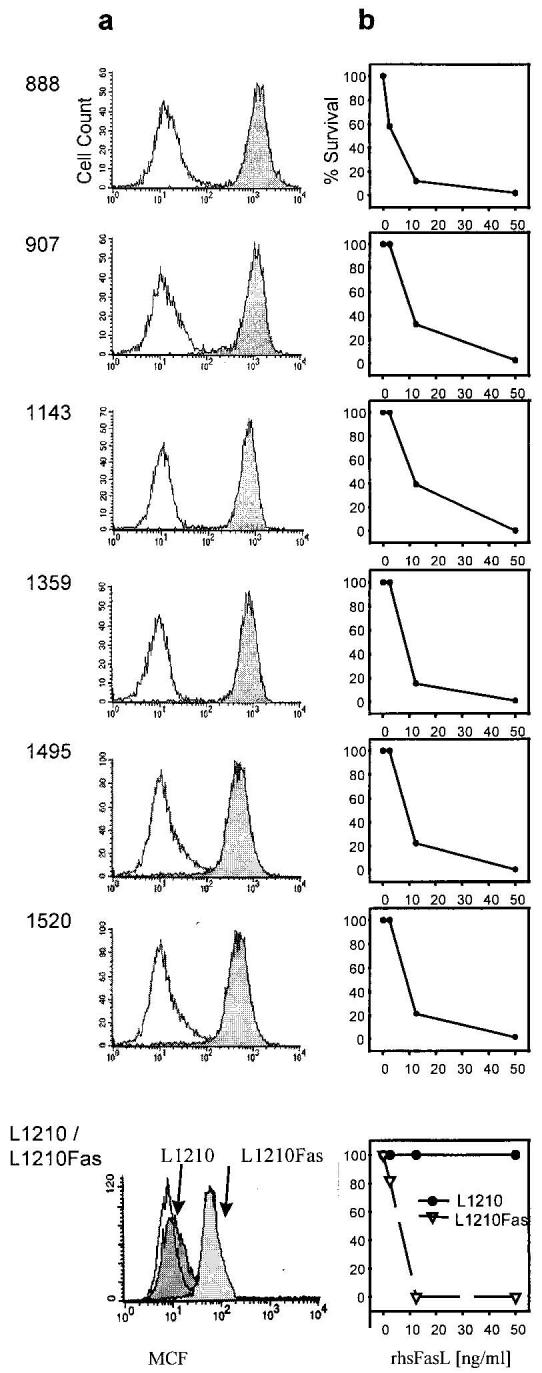

Tumor-specific CD8+ T cells lines express surface Fas and are highly sensitive to FasL-mediated apoptosis

To begin to delineate the role of Fas and FasL in the above phenomena, tumor-specific CD8+ T cells were analyzed for Fas surface expression by flow cytometry and their sensitivity to FasL was quantified by incubation with increasing concentrations of recombinant human soluble FasL (rhsFasL). All CD8+ T cells lines expressed high basal levels of Fas on their surface (Fig. 3a). This expression was relatively uniform across different lines and on average four times as high as on the human T cell leukemia line Jurkat, which is often used as a Fas+/Fas-sensitive target (data not shown). This high surface expression correlated with a uniformly high susceptibility to FasL-induced apoptotic death with an LD50 of ∼10ng/ml at 12 h. (Although sFasL has recently been shown to be 1,000-fold less active than the membrane-bound form (8), the rhsFasL used in the present study is a longer form than the one processed by metalloendoproteases, and all assays were done in the presence of an enhancer protein, which causes aggregation of rhsFasL, Fig. 3b.) This LD50 is almost as low as for L1210 cells transfected with the murine Fas (L1210-Fas). Incubation with TNF-α did not cause any apoptosis (data not shown). The apoptotic mode of death was confirmed by Annexin/propidium iodide staining 4–6 h after treatment with rhsFasL (data not shown). The susceptibility to the native membrane-bound form of FasL was further confirmed by incubating CD8+ T cells with activated allogeneic PBMC; anti-Fas mAb FM-3 effectively blocked 60% of induced death (shown for one representative line in Fig. 4).

FIGURE 3.

Tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells express high levels of Fas and are sensitive to apoptosis induced by rhsFasL. a, CD8+ T cells were stained with anti-Fas mAb (Ab-2) or irrelevant control IgG. Stainings were reproduce multiple times, and similar results were obtained with a different Ab (Ab-3, data not shown). In addition, surface Fas staining is shown for L1210 and L1210Fas used as target cells. b, T cell lines were incubated in increasing concentrations of recombinant rhsFasL (in the presence of 1 μg/ml enhancer protein), and cell viability was determined at 12 h. L1210 (Fas-resistant) and L1210Fas (Fas-sensitive) lines are shown as controls. Data represent one of two experiments that yielded similar results.

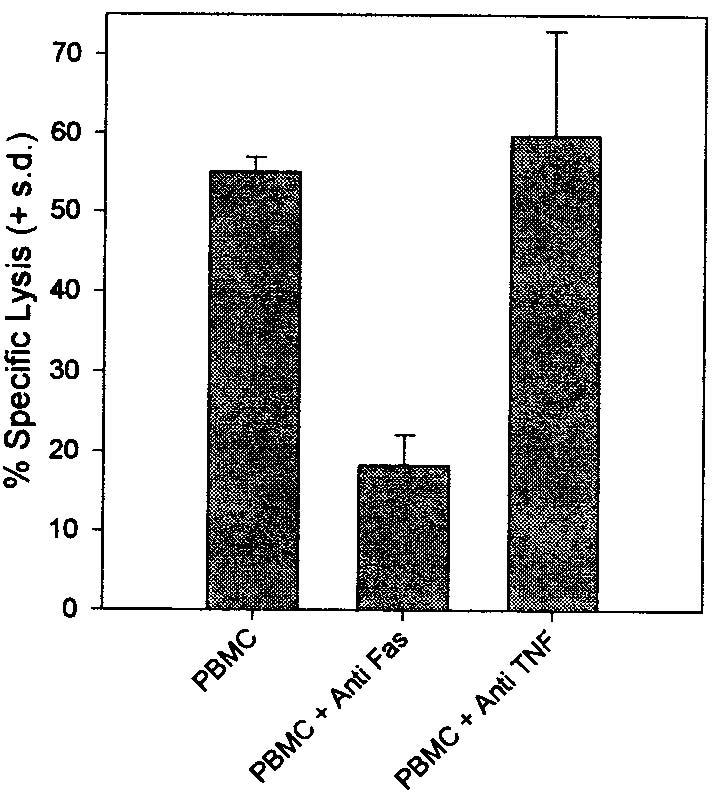

FIGURE 4.

Tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells are killed through the Fas pathway by activated allogeneic lymphocytes. Line 1495 was coincubated at an E:T of 1:1 with PMA and ionomycin-activated allogeneic PBMC in the presence or absence of anti-Fas (FM-3, 5 μg/ml) or anti-TNF-α (5 μg/ml) blocking Abs for 16 h, and specific lysis was determined by a standard 51Cr release assay. Similar results were obtained with an additional CD8+ T cell line (data not shown).

Ligation of TCR induces Fas-dependent apoptosis

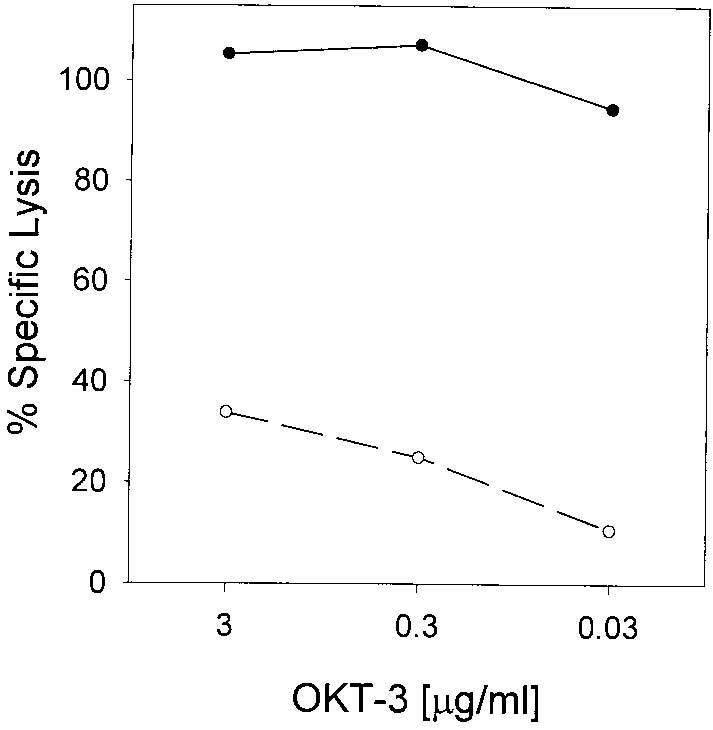

Despite repeated attempts with several different Abs, we failed to detect specific surface expression of FasL by FACS, consistent with several recent reports of the nonspecific binding of some of these reagents (9, 10). As anti-CD3 stimulation with the mAb OKT-3 is an often used model of TCR activation, which can cause Fas-dependent apoptosis in prestimulated T cells (11-13), we explored the effects of TCR ligation (in the absence of a second cell that may or may not express FasL) on the survival of the anti-tumor T cell cultures by incubation on plate-bound anti-CD3. Activation induced the apoptosis of ∼80% of the cells in these CD8+ T cell lines, and 60–100% of this death was blocked by anti-Fas mAb (Fig. 5a). Anti-TNF-α failed to block this death (data not shown). Similarly, anti-Fas mAb could block the tumor-induced apoptosis, as shown for the T cell line 1143 (Fig. 5b) (similar results were obtained for T cell line 1520). To test the induction of active FasL on the cell surface of the activated T cells, L1210 and L1210Fas cells were used as targets for FasL-mediated cytotoxicity. T cells that had been activated on OKT-3 showed preferential lysis of Fas-transfected as compared with the parental L1210 cells (Shown for a representative line in Fig. 6). There was minimal lysis of L1210 or L1210Fas by unactivated T cells (not shown). None of the melanoma tumor cells used in this study induced apoptosis of L1210/L1201Fas or expressed FasL mRNA, as assessed by RT-PCR, whereas FasL mRNA was induced by anti-CD3 stimulation of tumor-reactive lymphocytes (14).

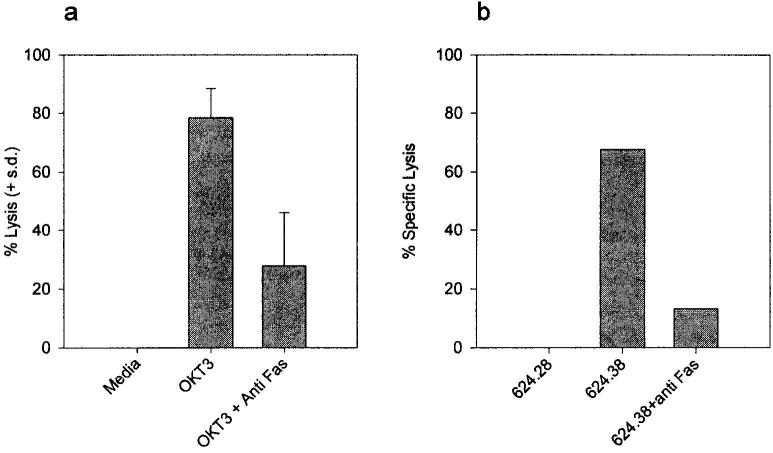

FIGURE 5.

AICD by anti-CD3 or cognate target interaction is Fas mediated. a, Activation of T cells by plate-bound OKT-3 induces Fas-mediated apoptosis. The six T cell lines were plated in wells precoated with 10 μg/ml OKT-3, in the presence or absence of anti-Fas mAb FM-3 (5 μg/ml), and viability was determined after 20 h. Data are plotted as the mean lysis of all six lines and represent one of at least three experiments that yielded similar results. Similar results were obtained with the caspase inhibitor BAF, but not with the control inhibitor z-FA or anti-TNF-α mAb (data not shown). b, Anti-Fas mAb block tumor-induced T cell apoptosis. 51Cr-labeled T cell line 1143 was incubated at an E:T ratio of 1:1 with 624.28 (HLA-A2−) or 624.38 (HLA-A2high) in the presence or absence of anti-Fas mAb FM-3 (5 μg/ml) for 16 h, following which the supernatants were harvested for 51Cr release. Similar results were obtained for line 1520 (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Activation induces functional FasL expression in tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Line 1143 was plated in wells precoated with indicated concentrations of OKT-3 for 4h, harvested, and cocultured for an additional 20 h with 51Cr-labeled L1210Fas (Fas-sensitive) (solid line, closed circles) or L1210 (Fas-resistant) (dashed line, open circles) cell lines at an E:T ratio of 1:1, after which supernatants were harvested and specific 51Cr release was measured. Data represent one of two experiments that yielded similar results.

Caspase inhibitors can rescue tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells from AICD without adversely affecting recognition or lysis of tumor targets

The previous results showed that the interaction of a tumor-specific CD8+ T cells with the cognate tumor target can cause significant TCR-mediated AICD. This death is known to occur later (16–24 h) than the perforin-mediated lysis of the tumor targets and is dependent upon the interaction of FasL with the Fas receptor. Thus, we hypothesized that this death could be blocked by specific inhibitors of the caspase pathway, which are crucial to transducing the Fas apoptotic signal, and indeed this was the case. The specific peptide inhibitor z-VAD could block nearly all apoptosis mediated by either anti-CD3 activation or interaction with cognate tumor (Fig. 7, a and b). Similar results were obtained with the caspase inhibitor BAF, but not with the control peptide z-FA (not shown). Although blocking this death pathway might enhance the ability of CD8+ T cells to kill tumor targets, it might also interfere with the susceptibility of the tumor cells to cytolysis. Thus, we examined the effects of blocking the Fas pathway at the surface (with blocking Abs), or downstream at the level of the caspases, on the recognition and lysis of tumor cells (Fig. 7, b and c). The caspase inhibitor z-VAD did not decrease the lysis of tumor cells by the CD8+ T cells and even increased the levels of IFN-γ secreted. At the same time, blocking with the anti-Fas Ab FM-3 consistently led to a small increase in the level of tumor lysis, while IFN-γ levels remained as high. These data demonstrate that it is possible to abrogate the detrimental effect of the T cell-tumor interaction on the T cell without interfering with the lysis of the tumor cell.

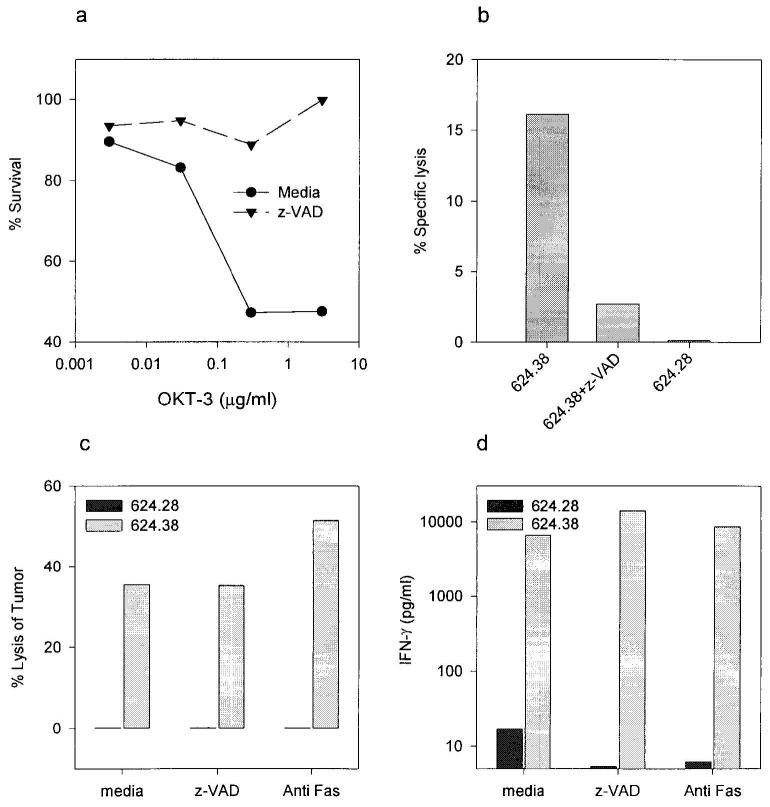

FIGURE 7.

Blocking the caspase pathway can abrogate AICD of CD8+ T cells without adversely affecting recognition or lysis of tumor cells. a–b, z-VAD blocks both anti-CD3 and tumor cell-induced apoptosis of T cells. a, Wells were precoated with indicated concentrations of OKT-3, and CD8+ T cell line 1495 was added for 40 h in the presence or absence of z-VAD (50 μM), following which viability was determined by a WST-1 assay. b, 51Cr-labeled CD8+ T cell line 1143 was incubated at an E:T ratio of 1:1 with 624.28 (HLA-A2−) or 624.38 (HLA-A2high) in the presence or absence of z-VAD (50 μM) for 16 h, following which the supernatants were harvested for 51Cr release. c–d, Blocking the Fas pathway with anti-Fas mAb or caspase inhibition does not inhibit tumor cell lysis or IFN-γ secretion in response to coculture with cognate tumor cells. The T cell line 1143 was incubated at an E:T of 1:1 with the HLA-A2high melanoma clone 624.38 or the HLA-A2− subclone 624.28 in the presence or absence of the caspase inhibitor z-VAD (25 μM) or the anti-Fas mAb FM-3 (5 μg/ml). c, Lysis of the cognate tumor target in a 164-h 51Cr release cytotoxicity assay (the tumor targets were prelabeled). d, Concurrent 24-h IFN-γ secretion assay. All experiments were repeated at least twice, and similar results were obtained with line 1520 (data not shown).

Discussion

The function of anti-tumor CD8+ T cells is mediated by their recognition and activation by tumor cells bearing the appropriate Ag. The consequence of this activation on the subsequent viability of melanoma-reactive CTL lines has not been extensively studied. In our study, significant levels of AICD were found in tumor-reactive T cell lines when they were activated by either cognate tumor or TCR ligation with anti-CD3 mAb. It is known that upon repeated stimulation with Ag (particularly in the presence of IL-2), T cells become susceptible to the induction of apoptotic cell death, mediated by FasL binding to the Fas receptor (belonging, respectively, to the TNF and TNF receptor families) (11-13, 15). This form of AICD has been dubbed “propriocidal regulation” and is postulated to be one of the central mechanisms by which T cell responses are turned off during and after an antigenic stimulation (16). The physiological importance of this interaction is shown by the genetic defects in the Fas-FasL pathway, which result in lymphoproliferation both in mice (gld and lpr strains) and in humans suffering from autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (17). The AICD observed in our study was a result of the expression of FasL and the engagement of the Fas receptor and did not operate through TNF-α, consistent with a previous report where TNF-α was found to function as a growth factor in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (18).

The expression of FasL has been found in nonlymphoid organs, such as the testis and the anterior chamber of the eye, and presumably accounts for their “immune-privileged” status. Of specific interest has been the description of FasL expression in some tumors, notably melanoma (5), hepatocellular carcinoma (19), and lung cancers (20), where its expression has been postulated to account for specific immune suppression by deleting Fas+ tumor-reactive T cells. This hypothesis would predict that the T cell lines used in our study, being highly susceptible to FasL, would be killed by melanoma cells in an MHC-unrestricted fashion. However, contrary to prediction, these T cells were lysed only when cocultured with the cognate tumor target. In theory, TCR engagement might be a prerequisite for Fas-mediated apoptosis (21), but as these T cell lines were highly susceptible to rhsFasL in the absence of TCR engagement, the data is not consistent with FasL expression by melanoma cells. Furthermore, in concurrent studies we have not found any expression of FasL either by a functional assay or by RT-PCR with intron-spanning primers in over 20 melanoma lines (including those used in this study) chosen at random from the large bank of melanoma tumor lines established in our laboratory (14). As the T cell lysis was inhibited by blocking the Fas pathway, we conclude that upon activation by the cognate tumor the T cells themselves express FasL and undergo suicidal or fratricidal apoptosis.

Rivoltini et al. (22) recently published their findings on the relative resistance of four melanoma tumor-reactive CTL clones to FasL, which was ostensibly expressed by some of the melanoma cell lines. However, the expression of FasL by melanoma cells was based on FACS staining with a polyclonal Ab (C-20) that since then has been reported not to bind specifically to FasL (9, 10). As all the cytotoxic activity was demonstrated after a week of coincubation with the autologous tumor, AICD was apparently not induced in their T cell clones by the interaction with tumor. T cell clones, in comparison with the lines used in the present study, might be relatively resistant to FasL either as consequence of different in vitro conditions (cloning vs high-dose IL-2) or possibly biased selection of Fas resistant cells by the cloning procedure. Our data do agree on two key issues: 1) there is no FasL toxicity mediated by FasL expression on melanoma cells toward Fas-expressing tumor-reactive T cells, and 2) Fas/FasL is not used by the T cells to mediate lysis of tumor cells. This latter finding underlies our ability to block the T cell suicide without blocking the tumor lysis.

The molecular pathway leading to Fas-mediated apoptosis has been shown to depend upon a cascade of Caspase proteases (23, 24). We have employed the previously characterized peptide inhibitors of this pathway to block the death of the tumor-reactive CTL. The two peptide analogues, Cbz-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethyl ketone (z-VAD-FMK) and its truncated analogue Boc-Asp(OMe)- fluoromethyl ketone (BD-FMK or BAF), which can block caspase 3 but not IL-1β-converting enzyme (caspase 1), have been shown to inhibit, at similar concentrations, anti-CD3/Fas-induced death in both thymocytes and activated T cell blasts (25). Moreover, in a model of fulminant hepatic failure leading to death of mice injected with an activating anti-Fas Ab, in vivo administration of z-VAD could prevent liver destruction and death (26). These inhibitors could prevent the AICD of anti-CD3 or tumor-stimulated T cells in our current study. As z-VAD has been shown not only to block the death but to enable the concomitant proliferation of Jurkat cells (27), using z-VAD concurrently with Ag (or anti-CD3) stimulation in vitro might enable a more efficient expansion of Ag-specific T cells. Blocking apoptosis in vivo, while potentially enhancing the ability of reactive T cells to kill tumor targets, might also interfere with the susceptibility of the tumor cells to cytolysis if their death involves Fas or caspases. Blocking lymphocyte apoptosis with the caspase inhibitor z-VAD did not decrease the lysis of tumor cells by CTL in our study, and even increased slightly the levels of IFN-γ secreted. Thus, blocking the Fas/caspase pathway did not impair melanoma tumor cell lysis, consistent with the near-complete absence of surface Fas in the melanoma lines (data not shown). Although granzyme B, the lytic enzyme of the major cytotoxicity pathway of CTL, is a serine protease with a specificity similar to that of caspase (Asp at P1) and has been reported to activate caspases (28, 29), these same peptide inhibitors (z-VAD and BAF) were shown to abrogate Fas-induced but not granzyme-induced target cell lysis (30). The accepted paradigm is that Fas-mediated cytotoxicity accounts for a minor lytic pathway that functions mostly in interactions between lymphocytes themselves. The expected exception would occur when a tumor arises from a hematopoetic origin; CD8+ T cells have been shown to kill Fas-expressing acute myeloid leukemia cells via the Fas pathway (31).

To summarize, the interaction of melanoma tumor-derived reactive CTL with the cognate tumor Ag induces Fas-dependent apoptosis of the CTL, where FasL is expressed by the tumor-reactive lymphocytes and not by the tumor cells. This sensitivity to AICD might be a limiting factor in the in vivo efficiency of such CTL when adoptively transferred to patients. The demonstration that this deletion is blockable with either anti-Fas Abs peptide inhibitors of caspase proteases without adversely interfering with recognition or lysis of tumor cells provides a possible method to modulate this susceptibility in vivo to enhance anti-tumor immune responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Karas (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for helpful suggestions and discussions, Dr. P. A. Henkart (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for providing useful reagents, and A. Mixon for technical assistance with FACS analysis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AICD, activation-induced cell death; FasL, Fas ligand; rhsFasL, recombinant human soluble FasL.

References

- 1.Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Weber JS, Parkinson DR, Seipp CA, Einhorn JH, White DE. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin 2. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.15.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee DS, White DE, Hurst R, Rosenberg SA, Yang JC. Patterns of relapse and response to retreatment in patients with metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma who responded to interleukin-2-based immunotherapy. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 1998;4:86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Jennings C, Sakaguchi K, Kang X, Southwood S, Robbins PF, Sette A, Appella E, Rosenberg SA. Recognition of multiple epitopes in the human melanoma antigen gp100 by tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor regression. J. Immunol. 1995;154:3961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pockaj BA, Sherry RM, Wei JP, Yannelli JR, Carter CS, Leitman SF, Carasquillo JA, Steinberg SM, Rosenberg SA, Yang JC. Localization of 111indium-labeled tumor infiltrating lymphocytes to tumor in patients receiving adoptive immunotherapy: augmentation with cyclophosphamide and correlation with response. Cancer. 1994;73:1731. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940315)73:6<1731::aid-cncr2820730630>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahne M, Rimoldi D, Schroter M, Romero P, Schreier M, French LE, Schneider P, Bornand T, Fontana A, Lienard D, Cerottini J, Tschopp J. Melanoma cell expression of Fas(Apo-1/CD95) ligand: implications for tumor immune escape. Science. 1996;274:1363. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topalian SL, Muul LM, Solomon D, Rosenberg SA. Expansion of human tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for use in immunotherapy trials. J. Immunol. Methods. 1987;102:127. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(87)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouvier E, Luciani MF, Golstein P. Fas involvement in Ca(2+)-independent T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:195. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider P, Holler N, Bodmer JL, Hahne M, Frei K, Fontana A, Tschopp J. Conversion of membrane-bound Fas(CD95) ligand to its soluble form is associated with downregulation of its proapoptotic activity and loss of liver toxicity. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1205. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith D, Sieg S, Kaplan D. Technical note: aberrant detection of cell surface Fas ligand with anti-peptide antibodies. J. Immunol. 1998;160:4159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiedler P, Schaetzlein CE, Eibel H. Constitutive expression of FasL in thyrocytes. Science. 1998;279:2015a. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhein J, Walczak H, Baumler C, Debatin KM, Krammer PH. Autocrine T-cell suicide mediated by APO-1/(Fas/CD95) Nature. 1995;373:438. doi: 10.1038/373438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner T, Mogil RJ, LaFace D, Yoo NJ, Mahboubi A, Echeverri F, Martin SJ, Force WR, Lynch DH, Ware CF. Cell-autonomous Fas (CD95)/Fas-ligand interaction mediates activation-induced apoptosis in T-cell hybridomas. Nature. 1995;373:441. doi: 10.1038/373441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ju ST, Panka DJ, Cui H, Ettinger R, el-Khatib M, Sherr DH, Stanger BZ, Marshak-Rothstein A. Fas(CD95)/FasL interactions required for programmed cell death after T-cell activation. Nature. 1995;373:444. doi: 10.1038/373444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chappell DB, Zaks TZ, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Inflammation or immunosuppression: human melanoma cells do not express Fas (Apo-1/CD95) ligand. Cancer Res. 1999;59:59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenardo MJ. Interleukin-2 programs mouse αβ T lymphocytes for apoptosis. Nature. 1991;353:858. doi: 10.1038/353858a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenardo MJ. The molecular regulation of lymphocyte apoptosis. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:1. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher GH, Rosenberg FJ, Straus SE, Dale JK, Middleton LA, Lin AY, Strober W, Lenardo MJ, Puck JM. Dominant interfering Fas gene mutations impair apoptosis in a human autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Cell. 1995;81:935. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trentin L, Zambello R, Bulian P, Cerutti A, Enthammer C, Cassatella M, Nitti D, Lise M, Agostini C, Semenzato G. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes bear the 75 kDa tumour necrosis factor receptor. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;71:240. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiraki K, Tsuji N, Shioda T, Isselbacher KJ, Takahashi H. Expression of Fas ligand in liver metastases of human colonic adenocarcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niehans GA, Brunner T, Frizelle SP, Liston JC, Salerno CT, Knapp DJ, Green DR, Kratzke RA. Human lung carcinomas express Fas ligand. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong B, Arron J, Choi Y. T cell receptor signals enhance susceptibility to Fas-mediated apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1939. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivoltini L, Radrizzani M, Accornero P, Squarcina P, Chiodoni C, Mazzocchi A, Castelli C, Tarsini P, Viggiano V, Belli F, Colombo MP, Parmiani G. Human melanoma-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ CTL clones resist Fas ligand-induced apoptosis and use Fas/Fas ligand-independent mechanisms for tumor killing. J. Immunol. 1998;161:1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirata H, Takahashi A, Kobayashi S, Yonehara S, Sawai H, Okazaki T, Yamamoto K, Sasada M. Caspases are activated in a branched pro-tease cascade and control distinct downstream processes in Fas-induced apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:587. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller DK. The role of the caspase family of cysteine proteases in apoptosis. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:35. doi: 10.1006/smim.1996.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarin A, Wu ML, Henkart PA. Different interleukin-1β converting enzyme (ICE) family protease requirements for the apoptotic death of T lymphocytes triggered by diverse stimuli. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:2445. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez I, Matsuura K, Ody C, Nagata S, Vassalli P. Systemic injection of a tripeptide inhibits the intracellular activation of CPP32-like proteases in vivo and fully protects mice against Fas-mediated fulminant liver destruction and death. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:2067. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longthorne VL, Williams GT. Caspase activity is required for commitment to Fas-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J. 1997;16:3805. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinnaiyan AM, Hanna WL, Orth K, Duan H, Poirier GG, Froelich CJ, Dixit VM. Cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B activates the apoptotic protease ICE-LAP3. Curr. Biol. 1996;6:897. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darmon AJ, Nicholson DW, Bleackley RC. Activation of the apoptotic protease CPP32 by cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B. Nature. 1995;377:446. doi: 10.1038/377446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarin A, Williams MS, Alexander-Miller MA, Berzofsky JA, Zacharchuk CM, Henkart PA. Target cell lysis by CTL granule exocytosis is independent of ICE/Ced-3 family proteases. Immunity. 1997;6:209. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komada Y, Zhou YW, Zhang XL, Chen TX, Tanaka S, Azuma E, Sakurai M. Fas/APO-1 (CD95)-mediated cytotoxicity is responsible for the apoptotic cell death of leukaemic cells induced by interleukin-2-activated T cells. Br. J. Haematol. 1997;96:147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.8742505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]