Abstract

This research uses analysis of qualitative interviews with 10 battered welfare clients and 15 frontline welfare workers to examine the implementation of the Family Violence Option (FVO) under welfare reform. States adopting the FVO agree to screen for domestic violence, refer identified victims to community resources, and waive program requirements that would endanger the women or with which they are unable to comply. The analyses find that none of the 10 clients in this study received these services. This lack of services reflects four critical disjunctures between the formal policy and the policy experienced by the clients. It also reveals several more basic structural factors that provide conflicting mandates to frontline workers. Frontline workers’ discretionary behaviors enforce core rules related to welfare eligibility and reduce welfare caseloads but do not provide violencerelated services to victims.

After enacting welfare reform through the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA; U.S. Public Law 104-193 [1996]), lawmakers agreed that domestic violence poses a considerable risk to women receiving welfare payments. Advocates successfully argued that welfare reform’s new demands, such as universal child support enforcement, mandatory work requirements, and strict time limits, might endanger women attempting to flee battering relationships. Out of concern for the immediate safety of these women and in an acknowledgment of domestic violence’s long-term effects on both physical and mental health, policy makers passed an amendment to PRWORA, the Family Violence Option (FVO; 42 U.S. Code 602 [a] 7 [2005]), which states could voluntarily agree to offer to welfare recipients. This amendment mandates that participating states provide three basic services: screen all welfare applicants for domestic violence, provide identified victims with appropriate referrals to community resources, and waive program provisions such as time limits, child support enforcement, and work requirements if these would endanger a woman or were beyond her current ability to comply because of domestic violence. Although the majority of states have voluntarily adopted the FVO, preliminary reports from the field indicate that few women are receiving the types of assistance provided through the policy (Lein et al. 2001; Levin 2001; Hagen and Owens-Manley 2002; Postmus 2004).

While literature on the characteristics of battered welfare recipients is growing (for recent reviews, see Tolman and Raphael 2001; Riger and Staggs 2004), far fewer studies tackle the question of the implementation of the FVO. The current article draws on a “bottom-up” (Schram 1995, 40) approach to study policy implementation by understanding the experiences of clients and the practices of frontline workers as they carry out policy-directed functions. As Sanford Schram (1995) notes, the bottom-up approach emphasizes the subjective, narrative, and situated nature of experience. Much welfare policy research assumes a managerial perspective that has limited relevance to the day-to-day problems confronting women who rely on the social welfare safety net (Schram 1995). Examining policy implementation processes through the bottom-up lens refocuses attention on the accounts of those who have the least access and power in the discourses concerning welfare policy.

The purpose of this exploratory research is to use client and frontline worker perspectives to identify processes associated with the implementation of the FVO. The article uses qualitative interpretive methods to describe implementation of the FVO by comparing the reports of battered women receiving welfare with the issues raised by frontline workers. Through the juxtaposition of these perspectives, it is possible to identify varying disjunctures between the stated policy process and the process encountered by the clients in the welfare system. The approach enables exploration of the institutional forces that influence caseworker behavior at critical points in this interaction. By identifying systemic issues related to the implementation of this specific policy, this work also contributes to research on larger institutional forces that direct the discretionary activities of street-level bureaucrats. The actions of these workers, in turn, have significant effects on the lives of citizen clients (Lipsky 1980; Soss 1999).

This research was conducted in Louisiana during 2000 and 2001. The period falls 2 years after the state’s adoption of the FVO. The needs of impoverished battered women are particularly urgent in Louisiana, which consistently ranks in the top five states for the number of people living in poverty (Annie E. Casey Foundation 2004) and which has one of the highest rates of homicide of women by their intimate partners (Violence Policy Center 1999). The battered welfare clients interviewed for this study usually experienced profoundly dangerous (and potentially fatal) acts of violence at the hands of their partners. Even in this context of high need, none of the 10 women in this study received services through the FVO.

As will be shown in this analysis, the reasons for the lack of service provision are complex. Frontline workers respond to administrative pressures to decrease welfare caseloads through discretionary behaviors that reduce the possibility of identifying domestic violence as a problem. Such discretionary behaviors include rationing information about services and choosing not to ask women about domestic violence. Even when abuse is identified, workers prioritize enforcement of core welfare eligibility rules rather than provision of FVO-mandated services, such as referral to community resources and waiver of program requirements for victims. Historical distrust (Gordon 1994; Lindhorst and Leighninger 2003) of the welfare system affects clients’ willingness to disclose information that could increase vulnerability to the discretion of their welfare worker and, potentially, to the clients’ abusive partners.

Background

Discretion at the Front Lines of Policy Implementation

Street-level work is characterized by rule-saturated environments in which frontline workers, paradoxically, have significant discretion in deciding which rules apply and the vigor devoted to their application (Brodkin 1997). Agency policy makers may directly encourage frontline workers to exercise discretion in order to achieve program goals. Policy scholars also suggest that discretion may be an indirect response that workers adopt both as a self-interested coping response to manage the mismatch between agency capacity and client need (Lipsky 1980) and as an outcome of forming interpersonal relationships with clients (Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003). Workers in public bureaucracies chronically encounter significant resource limitations, large caseloads, and time pressures that force them to develop efficient procedures for processing clients. Michael Lipsky (1980) suggests that frontline workers use discretionary processes to cope with conflicts between their day-to-day work and the agency’s policies. Such processes might include focusing on core activities that afford a high level of visibility within the agency and changing conceptions of work goals.

Steven Maynard-Moody and Michael Musheno (2000) identify Lipsky’s rationale as the “state-agent narrative,” which emphasizes how workers use discretion to make their work “easier, safer, and more rewarding” (329). They extend this narrative by focusing on how frontline workers also act as “citizen agents” (Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2000, 343) by engaging in personal and emotional relationships with their clients. Citizen agent discretion develops as a response to frontline workers’ beliefs about the deservingness of their clients. Frontline workers base beliefs about deservingness on the information they glean through direct contact with their clients and through socialization by their work peers into a pragmatic worldview characteristic of frontline workers.

Clients experience the discretion of street-level bureaucrats through the quality of the relationship they have with their workers and through the decisions workers make about what information they share with clients. This discretion is also observed in how workers choose to ration services they can offer and in the rigor with which workers enforce agency rules (Meyers, Glaser, and MacDonald 1998). The decisions that workers make regarding their clients and the relationships between workers and clients are the concrete manifestation of the policy process. Frontline workers are able to assist, subvert, or sabotage the policy implementation process by shaping the actual experience of clients and, therefore, by determining policy outcomes (Meyers 1998; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2000).

In order to respond to legislative mandates imposed by welfare reform, welfare bureaucracies need to transform the organizational culture in ways that particularly affect frontline staff (U.S. General Accounting Office 1996; Hercik 1998; Relave 2001). Welfare systems are called on to change from delivering the routinized, depersonalized, “people sustaining” (Hasenfeld 1983, 5) product of cash assistance to offering a new product of economic self-sufficiency that requires “people transforming” activities (Meyers 1998, 3). This shift signals a transition from the focus on policing that has typified welfare agencies (Burt, Zweig, and Schlichter 2000) to one in which supportive, employment-oriented services predominate.

In this transformation, tensions emerge between policy makers’ requirements concerning numerical goals and the frontline workers’ need to provide services to clients. Even when policy makers and frontline workers share a long-term interest in the achievement of policy objectives, they often operate in the short term with distinctly different priorities: policy makers seek to satisfy stakeholder demands for visible results; frontline staff work to manage demands from above for efficient performance alongside clients’ expectations for responsive services. The efforts of street-level workers to balance these competing demands very often result in discretionary behaviors that may subvert or cause incomplete implementation of policy reforms (Meyers et al. 1998).

Preliminary Evaluations of the FVO

While the federal welfare program for families and children has a long history, domestic violence has been recognized only recently as a serious problem for many women interacting with the system. Although estimated levels of abuse vary depending on the measurement used, studies with welfare-reliant women indicate that between 12 and 23 percent of these women report having experienced domestic violence in the previous 12 months, and over two-thirds report serious physical abuse from a partner in their lifetime (for summaries of available prevalence data, see Raphael and Tolman 1997; Haennicke, Raphael, and Tolman 1998; Tolman and Raphael 2001). Studies of women making the transition from welfare to work note that experience of domestic violence increases the likelihood of dropping out of job placement activities (Brush 2000) and can have long-term effects on women’s capacity to work (Raphael 2000).

Despite the high prevalence of domestic violence among welfare recipients, few women appear to be receiving specialized services under the FVO policy. In Texas, for instance, less than one-half of 1 percent of clients in a demonstration program received services available under the FVO (Lein et al. 2001). In a comparable program in Chicago, welfare caseworkers referred approximately 3 percent of clients to specialized domestic violence services (Levin 2001). Explanations for the low rates of services provided under the FVO highlight client-related dynamics, such as concerns about disclosure (Postmus 2004), and wrestle with the question of whether women benefit by requesting waivers from program rules (Pearson, Griswold, and Thoennes 2001). So, too, Laura Lein and associates (2001) find that clients’ attention is consumed by other significant challenges, such as housing and transportation.

Jan Hagen and Judith Owens-Manley (2002) provide one of the few studies of implementation from the perspective of the welfare caseworkers; they present workers with hypothetical client situations, asking the workers to specify whether they would provide FVO exemptions to these clients. Workers are found to be more likely to give an exemption if they believe the client is truthful and involved in efforts to improve her situation. However, they are found to be less likely to supply exemptions in client situations in which battered women returned to the abuser (as is frequently the case for women coping with domestic violence). Congruent with Maynard-Moody and Musheno’s thesis (2003), Hagen and Owens-Manley (2002) indicate that frontline workers use their discretionary powers to reward clients they believe are deserving (i.e., compliant and working toward agency goals).

In the particular instance of the FVO, general tensions related to discretion and organizational culture, as well as differences between the goals of policy makers and those of frontline workers, are amplified by the incongruence of welfare reform goals and the goals of the FVO. The overarching goal of PRWORA is to move women off welfare and into the workforce. Yet the FVO requires that exceptions be made for victims of domestic violence. These exceptions, given in the form of waivers that excuse the client from carrying out responsibilities mandated by welfare reform, often mean that the client’s time-limited welfare eligibility will be extended (Brandwein 1999). Little is known about how frontline workers are implementing these seemingly contradictory commands to move women off welfare and yet allow domestic violence victims to retain welfare benefits.

Background on Welfare Reform in Louisiana

Frontline welfare workers in Louisiana are required to conduct a multidimensional assessment of clients concerning barriers to employment and to formulate plans to address these barriers. They coordinate access to a complex array of support services, such as training, subsidized employment, child care, food stamps, and other community resources. They accomplish the goal of moving the client into the workforce through case decision making. This includes screening clients for eligibility, helping the client prepare individual responsibility plans, locating job placements, monitoring progress, and providing supportive services, such as child care. Welfare workers are required to have a 4-year college degree or 2 years of social service experience. While most welfare workers in Louisiana have a bachelor’s degree, few have an educational background in social services; in 2000, workers received an entry-level salary of $17,544 (Louisiana Department of Social Services [LaDSS], Office of Family Support 2000).

The welfare reform program adopted in Louisiana, the Family Independence Temporary Assistance Program (FITAP), is stricter than required by federal law. Perhaps as a result, the welfare caseload has decreased 72 percent in Louisiana since 1993. The state’s rate of reduction is well above the national mean of 56 percent (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] 2004). Louisiana has a 24-month time limit on receiving welfare benefits (as compared to the 5-year maximum required by Congress) and employs an optional fullfamily sanction in which both mother and children have their welfare payments stopped if the mother is judged by the department welfare worker to be noncompliant with agency regulations (LaDSS 1998). In 1999, when the first wave of recipients reached the 24-month time limit, approximately 4,200 people stopped receiving welfare benefits (DeParle 1999) in a caseload of approximately 41,000 (USDHHS 2004). Temporary exemptions from termination were given to another 2,000 people. Most of these were granted because mothers had physical health problems or were caring for a disabled child (Finch 1999). The state did not record any exemptions granted for reasons related to domestic violence.

In 1998, the year before time limits were imposed, Louisiana, along with 39 other states, adopted the FVO available under PRWORA.1 According to LaDSS policy, eligible clients are defined as those who are threatened with physical violence, sexual abuse, or extreme cruelty from another member of the household (LaDSS 1999). The policy requires screening to identify victims of domestic violence, referral to counseling and supportive services, and temporary waiver of program requirements if these “would make it more difficult for such individuals to escape domestic violence or unfairly penalize such individuals who are or have been victimized by such violence, or individuals who are at risk of further domestic violence” (LaDSS 1999, 1). The policy mandates worker discretion, stating that a case-by-case determination is required to ascertain whether a waiver is appropriate. No direction is given in the written policy as to how workers should determine whether a waiver should be given to a client who states she has been abused.

Method

Client Study

This study is part of a larger effort to evaluate outcomes related to welfare reform in Louisiana. A multimethod project was conducted from 1998 through 2001. The project employed a panel study of welfare recipients and a series of qualitative substudies (McElveen, Mancoske, and Lindhorst 2000). In the first year of the panel study, a team of social workers and master’s-level social work students surveyed a random sample of 570 welfare clients in one urban and two rural areas. In the second year of the study, 348 of the 570 respondents were reached and resurveyed. Participants in this qualitative study were recruited from the second-year study. Based on a single screening question, 18 of the 348 respondents reported physical abuse from a partner or former partner in the 12 months prior to the second interview. All respondents were female. Four of the women lived in a rural area that was outside the scope of the qualitative study. The 14 remaining women comprised the sample for the client portion of the current research. Of these women, 10 consented to indepth interviews. All 10 are African American. This reflects the fact that approximately 85 percent of the FITAP caseload is African American (LaDSS 1998). At the time of the second-year interviews, the average age of the interviewees was 33 years, and half had finished high school or obtained a general equivalency diploma. On average, participants have 2.9 children. With respect to age, education, and number of children, participants in this study resemble the members of the larger panel study.

During the interviews, the 10 women were asked to describe their experiences with abuse, their encounters with the welfare department, the help they received from other sources, their strengths, and their unmet needs. They were specifically asked if they were notified about the availability of good cause waivers for domestic violence and whether they were screened for abuse by a welfare worker. They were also asked about the reasons for their decisions concerning disclosure of their abuse and about any assistance they received from their caseworker if they did disclose. The first author and another social worker conducted the interviews in the fall of 2000 at a location determined by each woman to be safe and conducive to her willingness to discuss openly her situation.

The 10 women reported severe abusive behaviors by an intimate partner within the year prior to the interview. Each woman said that she ended the relationship, although former partners reportedly continued to threaten several of the participants. The women reported psychological abuse in the form of social isolation and threat of death; physical violence, both during the relationship and after their escape; sexual assault; and stalking that persisted for months and sometimes years after the relationship ended. Nine of the women said that the abuser threatened them or their children with death. Eight of the women expressed fear that the abuser would kill or seriously harm them or their children. The perpetrators attempted to kill six of the women in varied ways: stabbing, drowning, strangling, suffocation, and beating. The abuse described by almost all of these women was life threatening and severe, indicating that they were appropriate targets for assessment and intervention under the FVO.

Frontline Workers Study

During December 2000 and January 2001, interviews were conducted with 15 frontline workers who represented about 25 percent of the case management staff from two urban offices. These offices provided the highest volume of FITAP services in the state and served the majority of women interviewed for the qualitative study.2 Caseworkers were used as key informants about policy implementation because of their role as the frontline implementers of the FVO, their knowledge of current gaps in service delivery to their clients, and their awareness of the characteristics of the organization in which they worked. In order to gather workers’ impressions of organizational change efforts, administrators were asked to select randomly frontline workers who were in the agency prior to the changes mandated as a result of PRWORA. The 15 frontline staff represent seasoned workers employed by the state for tenures of 4–26 years. Six of the 15 caseworkers had more than 18 years of service. The workers had varied educational backgrounds: business (6), sociology (4), social work (2), fine arts (1), law (1), and nursing home administration (1). Workers managed an average of about 70 cases per month. One caseworker was assigned to a specialty unit working with hard-to-serve clients. She had a caseload of 10. Seven of the workers had between 50 and 80 cases. Seven had between 80 and 120 cases per month.

The interview protocol consisted of questions related to the workers’ tenure with the agency, the changes they experienced as the state’s welfare reform was implemented, the challenges workers face, their concept of success in their work, and their perceptions of both PRWORA and FITAP policy. They were asked to describe specifically the role and responsibilities of the caseworker in screening for and responding to domestic violence. They were also asked to describe their perceptions of what promoted and hindered client disclosure of abuse. To undergird the interview, methodologies, policies, procedures, and forms that the department used to guide its implementation of the FVO were also obtained. These materials are used to determine the formal process that was mandated by department policy. The policy was confirmed by discussions with department managers from the two units.

Interviews with clients and frontline workers were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data analysis began with the first transcriptions of interviews and informed the ongoing data collection process. Transcripts were organized and coded using the qualitative software program ATLAS.ti. In the first data coding process, each interview was read several times and then coded line by line. Codes were generated in two ways. First, categories arose from within the interview data (Marshall and Rossman 1999). For instance, descriptions of the types of abuse flowed directly from the statements of interviewees. Second, as suggested by Robert Bogdan and Sari Knopp Biklen (1998), a coding typology was constructed that identified information important to this study. Such information included critical events in the interaction between the client and the welfare caseworker, as well as interpretations that each made of the other’s behavior. Coded text was further analyzed to identify the contextual factors and processes related to policy implementation.

In order to ensure the rigor of the qualitative study, selected interviews were coded independently by the authors. Coding schemes were compared and discussed in order to reach consensus. The comparison of codes showed substantial agreement on the topic areas. The identified codes were then used to code the remaining transcripts. As insights were developed, they were checked against the data to verify their accuracy. Throughout the study, the qualitative findings were shared with research team members, who provided additional feedback on the process. The findings were also presented to and discussed with the caseworkers, who agreed with the overall findings.

Findings

We present findings related to the implementation of the FVO policy by describing the formal policy process and four primary points of disjuncture between the formal process and what clients experienced. We identify organizational factors that affect worker behavior in implementation of the FVO.

Formal Policy Process Related to Implementation of the Family Violence Option

The goals of the FVO can be met only if clients reveal to their welfare caseworker that they are victims of domestic violence. To make this voluntary disclosure, the client must perceive some benefit accruing from telling the caseworker about the abuse. In order to determine whether disclosure would be beneficial, clients need information about the intent and procedures of the policy. Because domestic violence has not traditionally been seen as a concern of the welfare system and because women historically have been accused of defrauding the system if they have an ongoing relationship with a man (Gordon 1994; Jones 1995; Lindhorst and Leighninger 2003), some effort is required from the agency to let clients know that this is an appropriate topic of discussion.

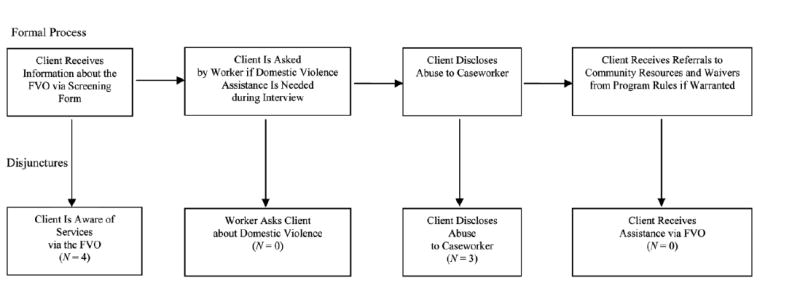

The Louisiana Department of Social Services adopted a formal protocol to implement the FVO policy. It requires notification and screening of all clients at their initial or reapplication visit (see fig. 1). Specifically, clients are to be given a form that describes their right to a good cause waiver from program requirements under the FVO. “Good cause” is the term used in describing acceptable administrative reasons for a client not to perform tasks mandated by FITAP administrative rules (LaDSS 2004). No written policy exists to direct workers on how to determine whether a waiver should be given to a client claiming abuse. The back of the form lists examples of emotional, economic, physical, and sexual abuse that constitute good cause (LaDSS 1999). Clients are asked to sign the statement and check off whether they wish to claim a family violence exemption from welfare program requirements. During the client’s assessment interview, caseworkers review the form with the client and ask if she needs assistance related to domestic violence. If the client discloses that she is being abused, the caseworker should provide referrals to appropriate community resources and assess whether the client would benefit from a good cause waiver that temporarily exempted her from FITAP time limits, mandatory work requirements, and child support enforcement. If the client’s situation warrants a waiver, the caseworker is charged with providing one.

Fig. 1.

Formal implementation process for FVO and critical disjunctures (N = 10). Note: FVO = Family Violence Option.

Our analysis examines how the clients progress through this policy process. We find that none of the clients proceeded through the system in the way outlined by the implementation process. Notably, only four women remember being given either written or verbal information about the FVO policy, and none recalls being verbally screened by her caseworker. None of the 10 clients received assistance available through the FVO, though all were eligible. At each of four steps in the policy implementation process, critical disjunctures are apparent between the process required by state administrative rules and what the women experienced.

First disjuncture: Clients are not aware of the FVO policy

Giving and withholding information are discretionary activities that public bureaucracies can use to ration services when resources are limited (Lipsky 1980). By choosing what information will be provided and how it will be provided to a client in the course of the client’s contact with the agency, bureaucracies can exert control over demands for a particular service. In the case of the FVO, the department mandates that all clients be notified about the policy in writing at the initial application or reapplication visit. Each of the women participated in an application or reapplication appointment in the 2 years prior to the interview, but only two of the women recalled ever seeing the good cause form. There is no clear reason why the remaining eight did not remember receiving written information on the FVO. The researchers were unable to verify the existence of completed good cause forms for these eight clients.

Bureaucracies can also control access to services through the use of confusing jargon and procedures that prevent clients from understanding how to operate effectively within the system (Lipsky 1980). Written information about the FVO is presented to LaDSS clients in a large packet of forms during the application process. The form is titled “Notification of Right to Claim Good Cause,” and nothing distinctive about the form’s title or front page indicates that the form has particular significance for victims of abuse. Clients are asked to check a box on the form if they desire to claim a good cause waiver. The box is located on the back at the form’s end; the procedure uses the least visually prominent area of the form to solicit the client’s disclosure. Although eight of the women in the sample did not recall receiving information on the FVO, it may be that some received the form and were not able to ascertain its importance to their situation.

Reliance on written materials to provide information requires that the client be able to read the materials given, recognize their importance to her particular situation, and understand the process that will be invoked if she checks the box. In a study of literacy among welfare recipients living in the nation’s 75 most populous counties, Alec Levenson, Elaine Reardon, and Stefanie Schmidt (1999) find that 76 percent of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) recipients are at the lowest literacy levels. One worker was particularly attuned to the problem of expecting women to absorb welfare rules information from paperwork, especially given the problem of illiteracy among her clients. However, when asked how clients were notified about domestic violence services, she reported that the agency relied on “client applications, and our addendums at the bottom of the application that address domestic violence.” Unsurprisingly, she reflected that she had not had any clients actually report domestic violence by indicating a need for services on a form.

Second disjuncture: Workers do not ask clients about domestic violence

Administrative policy requires that clients receive both written and verbal information about the availability of a good cause waiver for domestic violence. During the interview, regardless of whether the form is checked, caseworkers are directed to ask the client whether she needs a good cause waiver for reasons of domestic violence. Two clients stated that their caseworkers told them about the availability of FVO services (although they did not recall receiving this information in writing). None of the clients recalls being asked directly by the caseworker if she needed a good cause waiver or if she was experiencing domestic violence.

All but one of the workers reported a belief that it was the client’s responsibility to volunteer information about domestic violence, even though the FVO protocol requires that frontline workers specifically ask clients about abuse. Despite the formal requirement to screen clients, workers’ comments indicate that they did not accept the primary responsibility for ascertaining whether a client was experiencing domestic violence. They reported that it was the client’s responsibility to volunteer this information. As one worker noted, “It’s up to them to let us know. We don’t ask them. It’s on the application. … It’s nothing we really have to pursue if they don’t let us know.” A second worker made a similar comment, saying, “We don’t arbitrarily look for [domestic violence], and there are no ordinary guidelines or procedures to sniff it out.”

One caseworker stood out as the only person to acknowledge that it was within her job duties to verbally assess her clients for abuse. Not surprisingly, of all the workers interviewed, she reported the highest number of clients disclosing abuse. This caseworker developed a pattern of practice based on her personal experiences. That pattern led her to actively investigate the issue of abuse with her clients. When asked how she discovers that her clients are being battered, she said,

By talking to them and interviewing them. If they’re moving from place to place, I ask them, why are you moving like this? … I have the sympathy and empathy because I am a woman too, and I just talk to them and hear about certain things through conversation. I pick it up sometimes, you know. On our application, it does ask, are you a victim of domestic violence? And some of those people don’t check off “yes.” But as I have a conversation, I start discovering that … it’s like a relationship with them and they just come out with it.

Although each of the clients interviewed could have benefited from services available through the FVO, the majority indicated that they were unaware of the policy’s existence, having neither received written communication about it nor discussed the policy with a worker. Because clients did not know that their welfare caseworker could provide additional help with abuse, they had little reason to disclose this potentially difficult information to the caseworker.

Third disjuncture: Clients do not reveal abuse to their caseworker

The few clients who learned about the benefits and procedures related to the FVO were faced with a choice of whether to disclose their abuse to the worker or not. As has already been seen, the majority of frontline workers reportedly did not initiate this conversation with their clients, leaving it up to the client to raise the topic. For three of the four clients who were aware of services available under the FVO, this knowledge did not lead them to reveal that they were experiencing abuse. In the next section, we describe the situation of the client who knew about FVO services and disclosed abuse to her caseworker. Clients reported that they interpreted the worker’s silence about domestic violence to indicate that this was not an issue to discuss with the caseworker. One client who did not reveal her abuse said, “I didn’t think that was [the welfare system’s] business because nobody ever asked me about it.”

Whether the clients knew of the FVO or not, choosing not to discuss the abuse with their caseworker was a strategy that maintained their own and their children’s safety. Being secretive helped to minimize the effects of the abuse, enabling clients to hide from the abuser or to avoid confrontations with unsupportive family members. Some of the women said they would not disclose their abuse status to the welfare office because they were afraid the abuser would find out that they had revealed the violence and retaliate against them. While caseworkers were not required to report the abuse to law enforcement authorities, clients expressed concern that state workers would nevertheless reveal knowledge of the abuse during the course of child support enforcement procedures. Unless a woman can show good cause for noncompliance, PRWORA requires pursuit of child support as a part of the welfare application process (Brandwein 1999). Over half of the recipients were afraid that the perpetrator might punish them for trying to obtain child support, particularly if he discovered that the authorities knew of the abuse. These possibilities cause clients to worry intensely about the privacy of the information they give to their caseworker. One client reported, “I didn’t want to tell the worker [about the abuse] because I felt like that way everybody [would know] what was going on. I didn’t want to take my chances with him finding out. … You know, you may want to [tell], but you can’t tell the [caseworkers] everything because it is not safe people in there.”

Although several women said that they liked their workers in general, they didn’t feel that the worker helped them, and clients most frequently cited the conflictual nature of the client-worker relationship as the reason for not disclosing abuse. One woman described some of the common feelings clients expressed about their relationships with their caseworkers, stating, “I made a lot of mistakes in my life that put me in the position where I had to deal with the welfare. I’m quite sure I’m not the only one that made mistakes. Even the [caseworkers] make mistakes, but then they don’t look at us like we’re individuals. They try to demean us like we’re beneath them. Welfare doesn’t mean you have to be treated like trash.” Another observed, “You know, a lot of people go down to apply, and they ask you so many questions where you just say ‘the hell with it.’ You don’t have to answer. You know that you need it but you don’t want to go through this to get it. … Whether you tell them or not, they don’t help you. They just want to know your business.” These women express the reality that clients are suspicious of their workers’ motives and behavior (Seccombe, James, and Walter 1998). They typically view frontline staff as an obstacle to be negotiated rather than a support to trust in attempts to stabilize their lives.

Caseworkers also reported that clients rarely volunteer information about their domestic violence. Only four of the 15 caseworkers remembered that any client revealed a domestic abuse experience within the several years preceding the interview. The workers noted that clients may have several reasons for not divulging this personal experience; clients may remain silent because they fear retribution by the batterer or because they are ashamed. Caseworkers noted that the system also creates disincentives for revealing abuse. Clients are reluctant to reveal that they are in a relationship with a man because this information could potentially be used to deem the client ineligible for assistance under TANF and FITAP (a partner is expected to provide resources to the household). A general atmosphere of behavioral policing and punitive sanctions prevails in the state’s welfare system, and clients have a deep sense of wariness about volunteering personal information to their worker. Caseworkers recognize this attitude. One remarked, “I just assume they imagine that [domestic violence] is not any of my business. They come here for the basics, the money, the Medicaid, the child care—that’s what’s really important. They just don’t need to tell me. I’ve had one to come in with her lip swollen. She looked like she was mad at me. I asked what happened and she said, ‘None of your business.’”

Fourth disjuncture: Clients disclose their abuse but do not receive assistance

In spite of the multiple reasons for not divulging the abuse, three women did tell their caseworkers about the violence. Because of issues related to the abuse, each was about to be sanctioned off welfare for noncompliance with new agency regulations. However, their disclosure did not lead to referrals for or receipt of assistance through the department. One woman tells the following story about what happened when she disclosed the abuse to her caseworker:

When I went in, I filled out the paper, that is when I check boxed, you know, about domestic violence because [my son’s] father was due to be released [from prison after attempting to kill the client] and I really didn’t want to have anything to do with him. I was still afraid of him. But at that time when I went in and filled this out, they just asked me questions about him, they never asked about the domestic violence. They were more concerned about who the father was and did I know the place where he worked. I didn’t go up for the interview for the child support enforcement, because I didn’t know [the father’s] birth date. They wanted me to find out his birthday and Social Security number.

After the incident, this client was sanctioned off welfare for failure to comply with requirements regarding child support enforcement. The client was entitled to an exemption from those requirements under the FVO. Despite the worker’s knowledge of the abuse, no waiver was offered.

Another client who disclosed her abuse was sanctioned off welfare for noncompliance with work requirements. Her noncompliance was directly related to persistent mental health effects of the abuse she had endured. A few months before disclosing the abuse to her welfare caseworker, this woman was taken hostage by her abuser and stabbed. As a result of the event, she experienced symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, including flashbacks and severe panic attacks. The client also presented proof of her situation, providing the caseworker with documentation from the district attorney’s office and mental health social workers. She was 3 months pregnant with her sixth child when she disclosed the abuse to her caseworker and was having a difficult pregnancy. The mother recalled, “Just recently I couldn’t finish a [work] program. … [The program manager] called my worker and the worker told him that she thought I was writing the doctor’s statements myself. I said, ‘That’s not true,’ … [but] they didn’t want to hear it. ‘You’re cut off … until you participate.’ I said, ‘I don’t have a problem participating. I have limitations now because of the anxiety attacks. By me being pregnant, I can’t take any medication.’ The doctors are trying to find a medication to help me deal with the agoraphobia and the anxiety.” Despite the abuse, the documentation, and her pregnancy, this woman was not given an exemption under the FVO. When the sanction eliminated her welfare check, she was in danger of being evicted from her apartment in a public housing development. New rules under PRWORA require that public housing authorities deny rental subsidies to any resident whose loss of income has resulted from a welfare sanction (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2000).

The third survivor had reached the 24-month limit for FITAP receipt when she disclosed her abuse to her caseworker. Recovering from stab wounds inflicted by her abusive partner, she was unable to work and trying to care for two children. In disclosing the abuse to her worker, she provided documentation from law enforcement and newspaper clippings about the attack. In spite of this, her caseworker told her that she was not eligible for a waiver from the time limits and ended her financial assistance. As a result, this client relinquished custody of her children to another relative, who applied for welfare benefits in order to care for them.

Frontline workers verified that exemptions from new program requirements were rarely given to battered welfare clients. Only one worker provided a good cause waiver to a client because of domestic violence in the 2 years prior to the interview. Three of the workers were not aware that the policy existed or that domestic violence victims could be exempted from program requirements. If the clients encountered these workers, the workers’ lack of knowledge would likely prevent them from receiving assistance. However, 12 of the 15 frontline workers were aware of the exemptions available to clients for domestic violence but commonly held the view that they had little role in providing clients with access to these services. Expressing a perspective typical of the workers interviewed, one stated, “I had a lady assigned to go to a job training program, but she couldn’t go because even though she had a bond on the [perpetrator], he was hanging around the place she was supposed to go for the training. I think she was dropped from [TANF] and sanctioned because she didn’t attend. That was the reason … I can see [domestic violence] being lost in the shuffle with the amount of cases around here.” The worker did not acknowledge a possible role in preventing or addressing the client’s sanctions.

Organizational Factors That Inhibit Implementation of the FVO

Workers’ discretionary power is evident in these cases, but their failure to act indicates that such power is not used in the clients’ interest. These cases epitomize instances in which frontline workers can “lessen or intensify state harassment” (Withorn 1996, 273) through their discretionary practices. Why aren’t workers providing FVO services to clients who disclose their abuse and appeal for help? Possible answers to this question lead back to the ways in which discretion can be used as a coping strategy when agency goals and client needs are mismatched, as well as to the ways in which workers make decisions about the deservingness of their clients.

If only a handful of workers were failing to implement the policy mandates of the FVO, it might be possible to attribute this to poor skills, lack of awareness, or some other personal flaw of individual workers. However, clients and workers overwhelmingly concur that domestic violence is not talked about and assistance is not provided when abuse is identified. Therefore, it appears that deeper structural issues are responsible for these outcomes. It is possible from the interviews with frontline workers to identify three underlying issues that affect the implementation process: administrative focus on case closure, inadequate resources (i.e., time and skills) for assessing domestic violence, and worker attitudes related to the deservingness of clients.

Focus on case closure

Perhaps the most salient aspect of the frontline work environment is the pressure that workers experience to reduce caseloads. This demand appears to override any rationale for implementing the FVO. Caseworkers are at the bottom of a bureaucratic hierarchy in which they experience intense pressure from their supervisors, administrators, and the legislature to reduce the number of people on the welfare rolls. In interviews, workers noted that administrators compel them to justify decisions to exempt clients from certain requirements. This truncated focus produces a climate in which exempting victims of domestic violence creates a level of risk for the caseworker, as he or she is held personally accountable for continuing to provide financial assistance to clients. As one worker noted, “It puts a lot of pressure on the caseworker because those cases are reviewed and questioned often. And even though you say, ‘Well, the client has had problems,’ [they say,] ‘Okay, well, what about this or that?’ They are constantly pushing you, so you have to constantly push the client. It could be devastating for the client.”

Because of the administrative focus on case closure and because case closure serves as the primary measure of caseworker efficiency and productivity, it is in the frontline workers’ self-interest to minimize the number of clients who receive waivers and remain on the agency’s rolls. Each caseworker is judged against an official agency definition of success, and that definition is primarily based on the closure of welfare cases or the movement of clients into job-related activities. By focusing on case closures as the preferred outcomes, administrators tacitly reinforce a pressure against providing services to victims of domestic violence.

The agency definition of success conflicts with many of the workers’ personal beliefs about what constitutes success in their work. Several workers see their real mission as assisting individuals to become financially independent, not just leave welfare. These individuals view financial independence as a goal that they feel is in conflict with the larger agency mission to reduce the rolls. One worker, an employee of the agency for 10 years, noted, “It’s just mind boggling how we’re doing such a number game, and then we try to be a people person. You can’t do both.” In this context, allowing clients to continue to receive welfare while they address domestic violence contradicts the agency’s primary goal of moving people off the rolls as quickly as possible. Caught in the pressure to decrease their caseloads, frontline workers focus on core issues related to employability and case closure, minimizing and even overlooking domestic violence as a factor in their clients’ lives.

Inadequate personal and institutional resources

Caseworkers in this study recognized that abuse can be a significant problem for their clients. However, they have no incentive to prioritize inquiries about domestic violence in their interview with clients. A major concern expressed by frontline workers is the fact that there is inadequate time to complete thorough assessments with clients. Assessment processes require a prioritization of what information will be exchanged by whom in the limited time allotted. In these welfare offices, the initial interviews mainly focused on the explanation of the rules associated with receiving FITAP and on discussion of FITAP’s work-first approach. Workers reported that once they inform clients of the core directives related to welfare receipt, little time is left for the client to fully describe her situation. Workers respond to the time pressures they encounter by adopting discretionary strategies such as not asking questions that have complicated (i.e., timeconsuming) answers and relying on clients to volunteer information. Two workers’ replies typify the responses of the majority. One remarked, “You just don’t have time to pull [domestic violence] out of somebody, unless they come here with visible observations [bruises], which doesn’t happen often.” Another stated, “Well, we counsel [applicants] as much as we can. You have to think about the time period we have—we take as much time as we can. But, basically, with the job duties, you can’t really … spend the kind of time you want on each client as you wish you would be able to do.”

In identifying and addressing clients’ experiences of domestic violence, workers’ skills are also critically important. Frontline workers must possess and perceive that they possess the skills required for the tasks at hand. However, the workers in this study lacked confidence in their skills for working with domestic violence victims, and this lack of confidence contributed to their decisions not to raise the issue of abuse. A few caseworkers recall receiving training on how to talk with women about abuse, but this was generally perceived as inadequate in preparing workers for such conversations. Training is sporadic and not necessarily seen as valuable by many of the caseworkers. As one worker said, “I can’t remember the training. You have to understand—every time we turn around [it’s another training]. I just had a two-day training this week. You know, if it’s not one training, it’s another.” While training is necessary to prepare frontline workers for interactions with abuse victims, it is unlikely to focus worker attention on the issue of safety for battered women when organizational priorities and administrative oversight remain inconsistent with training.

Deservingness of clients

Assessing whether clients are victims of domestic violence and helping them to access services require that the caseworker have a supportive relationship with the client. Such a relationship stands in dramatic contrast to the expectations of workers who have been trained in eligibility determination and fraud prevention. The majority of the caseworkers told stories expressing the belief that clients tend to be irresponsible, dishonest, and unwilling to comply with the rules to which they commit as conditions of financial assistance. Caseworkers tend to distrust clients, requiring them to prove they are deserving before extending more than the required minimal help. The comments from two caseworkers typify this belief. One complained, “What gets me is that people don’t try to make it work for them. Anything, they stub their toe, they’re sick, it’s raining. They call and tell me they can’t come because it’s raining. But I’m on the other end waiting for you. So what does that mean? I came in the rain too.” So, too, a second caseworker remarked, “Once you’re here several months, a lot of your perceptions change and you become insensitive—you don’t look at clients as people. Just them and they do that and you have to do this to them, or you have to tell them this [emphasis from the respondent]—and you have missed it. The longer you are here, the more you can be like that—I’m trying hard not to shut down. Some people need help.”

Many of the workers in this study not only questioned the general deservingness of clients receiving TANF payments; some also expressed specific beliefs about the decisions that battered women should make in order to be seen as deserving of help. Although the majority of workers said that domestic violence is a legitimate cause for exemption from TANF requirements, some workers expressed the belief that battered women should demonstrate their commitment to ending the abusive relationship before they became eligible for assistance through the welfare department. As one worker noted, “If you’re going to stay in that situation, I can’t help you. But if you are going to take a step to get out of that situation, then it is feasible, and I can see it.”

Another said,

I think if they are in a shelter and they are fleeing, that’s a legitimate exemption. I don’t think that everybody that just comes in here and says they are a victim of domestic violence should be exempt. Because they need to get out of that situation. … I think it’s a good thing if they are feeling and trying to get themselves together. But if they are staying in the situation, then no. You have to make a move, make a change. But that’s not really a problem with us, because like I said, the clients don’t really tell us.

A third worker stated, “Domestic violence should be a short-term exemption. I don’t think it should take a year or so. I would say 3 to 6 months to get yourself situated. If you can catch the abuser and lock them up, you can just go on with your life.”

These workers have adopted certain stances about what a woman would have to do in order to prove that she deserved additional services related to domestic violence. However, leaving the relationship, fleeing to a shelter, and pursuing criminal justice interventions are not central components of the FVO. More crucially, research documents that a battered woman faces the greatest risk of being killed by her partner after she leaves the relationship (Campbell et al. 2003). Workers could increase the danger to the client if they believe that assistance should be contingent on the client’s willingness to leave the abusive relationship. The opinions of these workers may find expression in discretionary methods that they adopt to determine client worthiness for services.

Discussion

Welfare reform compels welfare bureaucracies to move from an organizational culture focused on policing clients to one that is invested in their support (Meyers 1998; Burt et al. 2000). This study illustrates some of the structural barriers that may prevent workers from recognizing and responding appropriately to domestic violence. Louisiana is one state where implementation of the FVO is curtailed in the face of strong mandates to reduce reliance on welfare. Given the optional nature of the FVO and the lack of federal or state administrative oversight in its implementation, it is not surprising that frontline workers see little institutional encouragement to engage with clients concerning the complex issue of domestic violence. Through its administrators and supervisors, the welfare system holds frontline workers accountable for core activities, such as moving clients into work or training and closing cases, as workers note in these interviews. No such accountability exists for services under the FVO.

Within the institution itself, caseworkers use both state agent and citizen agent rationales to justify their discretionary work actions (Lipsky 1980; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2000). From a state agent perspective, caseworkers use discretion to cope with institutional pressures by focusing their work on activities for which they are immediately accountable. Public agencies face chronic resource shortages in attempting to manage their identified service needs. One method for controlling demand is to structure the activities of frontline workers to maximize core components of service delivery, devoting limited or minimal attention to actions that are seen as peripheral to the agency’s mission. Significant resource limitations force frontline workers to develop efficient procedures for processing clients through the service system. Burdened with large caseloads, extensive reporting responsibilities, and a lack of confidence in their skills, caseworkers are not motivated to raise the issue of domestic violence with the women that they assist.

The citizen agent narrative suggests that frontline workers use their discretion to prioritize services for clients they see as deserving. Workers in this study express a general perception that welfare clients are only minimally deserving of help. This reflects a long-standing historical perception, accepted throughout society, concerning the moral worthiness of poor women (Gordon 1994; Jones 1995). Some workers further expressed a belief that women experiencing domestic violence need to take action to end the abuse before the worker will provide assistance. This finding is consistent with previous research, which suggests that frontline workers impose additional criteria on battered women rather than utilizing the services offered under the FVO to maximize women’s safety resources (Hagen and Owens-Manley 2002). Coupled with mounting evidence of the danger facing women who leave batterers (Campbell et al. 2003), this stance could contribute to increasing women’s risk instead of alleviating it.

Ironically, while clients experience the welfare system as adversarial, inhospitable, intrusive, and controlling, they are now expected to come forward and divulge information that many find embarrassing, distressing, or dangerous. So, too, in asking a client whether she is genuinely in danger, a worker must have some belief in the client’s fundamental honesty. The worker must also possess a willingness to pursue a conversation that could provoke anxiety because the absence of institutional and interpersonal support places workers in an environment that prevents this conversation from occurring. The result is that protective options such as the FVO are underutilized.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. This research is bound to the place and the time in which it was conducted. Because of the intensity of the problems of domestic violence and poverty, Louisiana provides a strong and compelling environment for the study of these issues. However, it is not representative of all other states. The experiences of frontline workers and clients in this study may differ from those in other states and also from those in other offices within Louisiana. Also, this study provides an initial exploration of the processes surrounding implementation of the FVO over a single period. While this snapshot captures realities of the workplace early in the implementation process, it does not reflect the evolution of procedures as the agency continues to refine service delivery efforts.

This study treats the descriptions of the clients and frontline workers as true representations of the actual conditions that each experiences. However, recall and social desirability may affect these depictions, as workers and clients try to present themselves in the best possible light. Both groups may exaggerate the constraints that they face or understate their own responsibility for the outcomes that occur. Bias may also be present in the recruitment process for the clients and the frontline workers. Clients were selected based on their self-report of abuse. Others may also have experienced abuse but failed to report it on the survey. The self-report procedures may bias the final sample in unknown ways. Frontline workers were to be randomly selected by administrators, but administrators may not have used a random method to choose the workers who participated. It is likely that, since administrators were aware that worker responses would be used to evaluate agency efforts, participants were chosen because of their perceived effectiveness and adherence to agency protocols.

Conclusion

This research provides a cautionary tale about the consequences of competing goals and structural barriers in the implementation of the Family Violence Option. As long as the dominant emphasis in welfare offices remains the reduction of the caseload, women’s legitimate safety concerns will be secondary. If welfare systems are to address the problems created by domestic violence for their clientele, changes will need to occur at multiple system levels. Federal, state, and frontline accountability is needed in decisions related to implementing the FVO. Such changes would be a place to start in transforming the system to make it more responsive to battered women’s needs.

Acknowledgments

This article was previously presented on October 27, 2001, at the third Trapped by Poverty/Trapped by Abuse conference in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The authors would like to thank Ronald J. Mancoske, Marcia K. Meyers, and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This research was supported by the Louisiana Department of Social Services and Southern University at New Orleans. All opinions expressed are those of the researchers and not of the department.

Footnotes

The 10 additional states made other provisions for providing services to battered women but did not formally adopt the Family Violence Option. See USDHHS (2000) for a summary of state choices regarding the FVO.

For reasons of confidentiality, the battered women and caseworkers in this qualitative study are not identified. For the same reason, this study does not identify the locations of interviews or the LaDSS offices involved. The workers who were interviewed may or may not have been the caseworkers for the clients interviewed for the study.

Contributor Information

Taryn Lindhorst, University of Washington.

Julianna D. Padgett, Southern University at New Orleans

References

- Annie E. Casey Foundation. Kids Count Data Book: State Profiles of Child Well-Being. Baltimore: Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan Robert C, Biklen Sari Knopp. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. 3. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brandwein Ruth A. Family Violence, Women, and Welfare. In: Brandwein Ruth A., editor. 3–14 Battered Women, Children, and Welfare Reform: The Ties That Bind. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin Evelyn Z. Inside the Welfare Contract: Discretion and Accountability in State Welfare Administration. Social Service Review. 1997;71(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brush Lisa D. Battering, Traumatic Stress, and Welfare-to-Work Transition. Violence against Women. 2000;6(10):1039–65. [Google Scholar]

- Burt Martha R, Zweig Janine M, Schlichter Kathryn. Report to the U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2000. Strategies for Addressing the Needs of Domestic Violence Victims within the TANF Program: The Experience of Seven Counties . [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Jacquelyn C, Webster Daniel, Koziol-McLain Jane, Block Carolyn, Campbell Doris, Curry Mary Ann, Gary Faye, et al. Risk Factors for Femicide in Abusive Relationships: Results from a Multisite Case Control Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(7):1089–97. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeParle Jason. As Benefits Expire, the Experts Worry. New York Times. 1999 October 10;:A1. [Google Scholar]

- Finch Susan. Welfare Reform Works for Many in LA. Times-Picayune/States-Item. 1999 January 10;:A1. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Linda. Pitied but Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare, 1890–1935. New York: Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haennicke Sheila B, Raphael Jody, Tolman Richard M. Project for Research on Welfare, Work, and Domestic Violence report. Taylor Institute and University of Michigan Research Development Center on Poverty, Risk and Mental Health; Chicago: 1998. Supplement 1 to Trapped by Poverty/Trapped by Abuse: New Evidence Documenting the Relationship between Domestic Violence and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen Jan L, Owens-Manley Judith. Social Work. 2. Vol. 47. 2002. Issues in Implementing TANF in New York: The Perspective of Frontline Workers; pp. 171–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfeld Yeheskel. Human Service Organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hercik Jeanette M. Issue Notes (Welfare Information Network, Finance Project, Washington, DC) no 7 Vol. 2. 1998. At the Front Line: Changing the Business of Welfare Reform. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Jacqueline. Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present. New York: Vintage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lein Laura, Jacquet Susan E, Lewis Carol M, Cole Patricia R, Williams Bernice B. With the Best of Intentions: Family Violence Option and Abused Women’s Needs. Violence against Women. 2001;7(2):193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson Alec R, Reardon Elaine, Schmidt Stefanie R. Report no. 10B. National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy; Cambridge, MA: 1999. Welfare, Jobs and Basic Skills: The Employment Prospects of Welfare Recipients in the Most Populous U.S. Counties . [Google Scholar]

- Levin Rebekah. Less than Ideal: The Reality of Implementing a Welfare-to-Work Program for Domestic Violence Victims and Survivors in Collaboration with the TANF Department. Violence against Women. 2001;7(2):211–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst Taryn, Leighninger Leslie. Ending welfare as we know it’ in 1960: Louisiana’s Suitable Home Law. Social Service Review. 2003;77(4):564–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky Michael. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Louisiana Department of Social Services (LaDSS) The Facts about Welfare and Food Stamps in Louisiana. Baton Rouge: LaDSS, Office of Family Support; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Louisiana Department of Social Services (LaDSS) FITAP Manual, Document no E-331-FTAP. Baton Rouge: LaDSS; 1999. Domestic Violence Option. [Google Scholar]

- Louisiana Department of Social Services (LaDSS) State of Louisiana Temporary Assistance for Needy Families State Plan. Baton Rouge: LaDSS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Louisiana Department of Social Services, Office of Family Support. [accessed July 18, 2000];Office of Family Support. 2000 http://www.dss.state.la.us/departments/ofs/index.html.

- Marshall Catherine, Rossman Gretchen B. Designing Qualitative Research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard-Moody Steven, Musheno Michael C. State Agent or Citizen Agent: Two Narratives of Discretion. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2000;10(2):329–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard-Moody Steven, Musheno Michael C. Cops, Teachers, Counselors: Stories from the Front Lines of Public Service. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McElveen Joy, Mancoske Ronald J, Lindhorst Taryn. Report to the Louisiana Department of Social Services. Southern University at New Orleans, Welfare Reform Research Project; New Orleans: 2000. The Impact of Welfare Reform on Louisiana’s Families: Year Two Panel Study Report. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers Marcia K. Report. Rockefeller Institute of Government; Albany, NY: 1998. Gaining Cooperation at the Front Lines of Service Delivery: Issues for the Implementation of Welfare Reform. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers Marcia K, Glaser Bonnie, MacDonald Karin. On the Front Lines of Welfare Delivery: Are Workers Implementing Policy Reforms? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1998;17(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson Jessica, Griswold Esther A, Thoennes Nancy. Balancing Safety and Self-Sufficiency: Lessons on Serving Victims of Domestic Violence for Child Support and Public Assistance Agencies. Violence against Women. 2001;7(2):176–92. [Google Scholar]

- Postmus Judy L. Battered and on Welfare: The Experiences of Women with the Family Violence Option. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 2004;31(2):113–23. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael Jody. Saving Bernice: Battered Women, Welfare, and Poverty. Boston: Northeastern University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael Jody, Tolman Richard M. Project for Research on Welfare, Work, and Domestic Violence report. Taylor Institute and University of Michigan Research Development Center on Poverty, Risk and Mental Health; Chicago: 1997. Trapped by Poverty/Trapped by Abuse: New Evidence Documenting the Relationship between Domestic Violence and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Relave Nanette. Issue Notes (Welfare Information Network, Finance Project, Washington, DC) no 4 Vol. 5. 2001. Using Case Management to Change the Front Lines of Welfare Service Delivery. [Google Scholar]

- Riger Stephanie, Staggs Susan L. Welfare Reform, Domestic Violence, and Employment: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know? Violence against Women. 2004;10(9):961–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schram Sanford F. Words of Welfare: The Poverty of Social Science and the Social Science of Poverty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Seccombe Karen, James Delores, Walters Kimberly Battle. They think you ain’t much of nothing’: The Social Construction of the Welfare Mother. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60(4):849–65. [Google Scholar]

- Soss Joe. Lessons of Welfare: Policy Design, Political Learning, and Political Action. American Political Science Review. 1999;93(2):363–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman Richard M, Raphael Jody. A Review of Research on Welfare and Domestic Violence. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;56(4):655–82. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Program: Third Annual Report to Congress, August 2000. Washington, DC: USDHHS, Administration for Children and Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) State by State Welfare Caseloads since 1993 (Families): Change in TANF Caseloads. 2004 http://www.acf.hhs.gov/news/stats/case-fam.htm.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. . Public notice no PIH 2000-11. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2000. Guidance on Establishing Cooperation Agreements for Economic Self-Sufficiency between Public Housing Agencies (PHAs) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) Agencies . [Google Scholar]

- U.S. General Accounting Office. . Report no GAO/HEHS-96-105. Washington, DC: U.S General Accounting Office; 1996. Welfare Waivers Implementation: States Work to Change Welfare Culture, Community Involvement, and Service Delivery . [Google Scholar]

- Violence Policy Center. . Report. Violence Policy Center; Washington, DC: 1999. When Men Murder Women: An Analysis of 1997 Homicide Data. [Google Scholar]

- Withorn Ann. For Better and for Worse: Women against Women in the Welfare State. In: Dujon Diane, Withorn Ann., editors. For Crying out Loud: Women’s Poverty in the United States. Boston: South End Press; 1996. pp. 269–85 . [Google Scholar]