Abstract

Estrogen deficiency in menopause is a major cause of osteoporosis in women. Estrogen acts to maintain the appropriate ratio between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts in part through the induction of osteoclast apoptosis. Recent studies have suggested a role for Fas ligand (FasL) in estrogen-induced osteoclast apoptosis by an autocrine mechanism involving osteoclasts alone. In contrast, we describe a paracrine mechanism in which estrogen affects osteoclast survival through the upregulation of FasL in osteoblasts (and not osteoclasts) leading to the apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts. We have characterized a cell-type-specific hormone-inducible enhancer located 86 kb downstream of the FasL gene as the target of estrogen receptor-alpha induction of FasL expression in osteoblasts. In addition, tamoxifen and raloxifene, two selective estrogen receptor modulators that have protective effects in bone, induce apoptosis in pre-osteoclasts by the same osteoblast-dependent mechanism. These results demonstrate that estrogen protects bone by inducing a paracrine signal originating in osteoblasts leading to the death of pre-osteoclasts and offer an important new target for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.

Keywords: bone, estrogen, Fas ligand, osteoblast, osteoclast

Introduction

Estrogen is an important regulator of female development, and also plays a role in the brain (Cutter et al, 2003), skin (Kanda and Watanabe, 2004), liver (Srivastava et al, 1997), hair (Ohnemus et al, 2005), adipocytes (Cooke and Naaz, 2004), immune system (Cutolo et al, 2004) and bone (Rickard et al, 1999), among other tissues. The effects of estrogen are mediated by two nuclear receptors: estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ). ERα and ERβ are both expressed in many cell types, but at lower levels than those found in reproductive tissues (Zallone, 2006).

Low circulating estrogen is an important risk factor for post-menopausal osteoporosis (Sambrook and Cooper, 2006). Estrogen and ERs are important for bone formation in humans (Smith et al, 1994) and mice (Windahl et al, 2002). Furthermore, decreased estrogen levels due to natural or surgically induced menopause lower bone mineral density in humans (Eastell, 2006) and rodents (Wronski et al, 1989). Women who are at risk for osteoporosis are treated currently with estrogen replacement therapy, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or bisphosphonates.

Estrogen has been shown to induce apoptosis in bone-resorbing osteoclasts (Kameda et al, 1997; Kousteni et al, 2002). Furthermore, estrogen is anti-apoptotic in osteoblasts, leading to an overall building of bone (Kousteni et al, 2002). ER knockout (ERKO) mice have an increase in the total number of osteoclasts due to the lack of estrogen-induced osteoclast apoptosis (Parikka et al, 2005). A recent study by Nakamura et al (2007), using osteoclast-specific ERα knockout mice suggested that ERα expression in osteoclasts was necessary for their apoptosis. In addition, these authors suggested an autocrine mechanism for the estrogen-induced apoptosis of osteoclasts involving the induction of Fas ligand (FasL) in these same cells.

To gain a better understanding of the mechanism by which estrogen induces FasL in bone leading to osteoclast apoptosis, we studied the effects of estrogen (and SERMs) on mouse and human osteoclast differentiation and survival in vitro and in vivo and on the expression of FasL in both osteoclasts and osteoblasts. In contrast to previous studies, we find that the induction of apoptosis by estrogen occurs at the pre-osteoclast stage of osteoclast development and that this requires the presence of osteoblasts and the estrogen induction of FasL expression in osteoblasts and not osteoclasts.

Results

Regulation of the development of mature osteoclasts by estradiol

Osteoclasts are derived from hematopoietic stem cells (Walker, 1975) differentiating from myeloid precursors in the presence of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (Boyle et al, 2003). Pre-osteoclasts, or mononuclear osteoclasts, are defined as mononuclear cells that stain positive for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and express cathepsin K mRNA (Supplementary Figure 1) (Hershey and Fisher, 2004). Fully differentiated osteoclasts are multinucleated, TRAP positive, and have increased expression of cathepsin K and calcitonin receptor mRNA (Supplementary Figure 1). To determine the effect of estrogen on osteoclast differentiation and survival, bone marrow cells were obtained from BALB/c mice and differentiated with RANKL and M-CSF in the presence or absence of 17β-estradiol (E2) for 8 days (Figure 1A). The majority of cells in these cultures are of the myeloid lineage; however, a small percentage of the surviving cells after 8 days in this culture system are of mesenchymal origin, including osteoblasts (see below). E2 inhibited, in a dose-dependent manner, mature osteoclast formation. As little as 0.1 nM E2 prevented the appearance of multinuclear osteoclasts. Treatment with 10 nM E2 caused death in most cells, and those remaining did not stain positive for TRAP. In addition, pre-osteoclasts treated with E2 for 6 days had decreased cathepsin K and calcitonin receptor mRNA levels (Figure 1B and C), supporting the conclusion that E2 inhibited mature osteoclast formation. A 3 h exposure to E2 in pre-osteoclasts or osteoclasts had no effect on cathepsin K mRNA (data not shown).

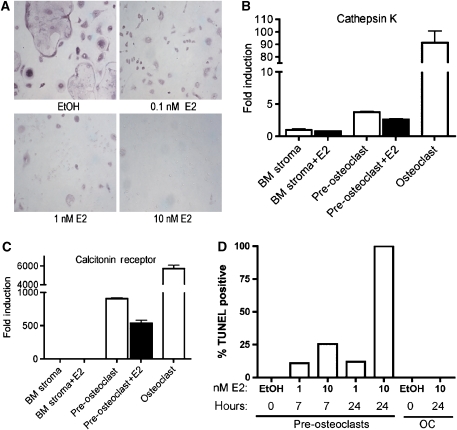

Figure 1.

Estrogen induces apoptosis in pre-osteoclasts and prevents the formation of mature osteoclasts. (A) Bone marrow was differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL for 8 days in the presence of ethanol (EtOH), 0.1 nM estradiol (E2), 1 nM E2 or 10 nM E2. Cells were then fixed and stained for TRAP. (B) The expression of cathepsin K mRNA or (C) calcitonin receptor mRNA was measured by quantitative real-time PCR from RNA isolated from bone marrow, pre-osteoclast and osteoclast cultures treated with or without 10 nM E2 for the entire course of differentiation. Fully differentiated osteoclasts treated with E2 were never formed and thus there is no value in this figure. The fold induction was normalized to β-actin mRNA. Error bars represent ±1 s.d. (D) Bone marrow was differentiated to the pre-osteoclast or osteoclast state with M-CSF and RANKL and then treated for 7 or 24 h with vehicle (EtOH), 1 nM E2 or 10 nM E2. Cells were fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Quantification was performed using a laser scanning cytometer. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

It has been previously demonstrated that estrogen induces apoptosis of osteoclasts, but its mechanism has not been fully elucidated (Kameda et al, 1997; Kousteni et al, 2002). In particular, the possibility that a small number of osteoblasts present in osteoclast cultures might be playing a role was not examined. To determine at what stage in osteoclast differentiation estrogen induces apoptosis, the effect of E2 was tested in pre-osteoclasts and fully differentiated osteoclasts. Apoptosis occurred in the TRAP-positive pre-osteoclasts (Figure 1D). This supports data by Sorensen et al (2006) that estrogen has no effect on the resorption or TRAP activity of mature osteoclasts. We then investigated the concentration and duration of estrogen treatment required for apoptosis. After 7 h of 1 nM E2 treatment, approximately 10% of pre-osteoclasts were apoptotic, as measured by the TUNEL assay, and 10 nM E2 treatment induced apoptosis in 25% of pre-osteoclasts (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 2). After 24 h of treatment with 10 nM E2, nearly 100% of cells were TUNEL positive (Figure 1D). Taken together, the data illustrate that E2 can block the formation of mature osteoclasts by inducing death at the pre-osteoclast stage.

Estrogen activates the Fas/FasL pathway

A recent paper by Nakamura et al (2007) suggests that estrogen induces FasL in osteoclasts to induce apoptosis in an autocrine manner. To verify that Fas and FasL were activated upon treatment with estrogen, E2-induced apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts was quantified in the presence or absence of a FasL neutralizing antibody. E2-mediated apoptosis was blocked in the presence of a neutralizing FasL antibody, confirming that E2-mediated apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts is FasL dependent (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Estrogen-induced apoptosis is mediated by the Fas/FasL pathway. (A) Pre-osteoclasts were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days and then treated for 16 h with vehicle (EtOH) or 10 nM E2, and either a control IgG or 5 pg/μl FasL neutralizing antibody. Cells were fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Quantification was performed using a laser scanning cytometer. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Pre-osteoclasts from wild-type, FasL-deficient mice (gld) and Fas-deficient mice (lpr) were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days and then treated for 16 h with vehicle control (EtOH) or 10 nM E2. Cells were fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Quantification was performed using a laser scanning cytometer. (C) Fas and (D) FasL mRNA levels were analyzed by quantitative PCR from RNA obtained from bone marrow stroma (BM stroma), pre-osteoclasts (pre-OC) with and without 10 nM E2, osteoclasts with and without 10 nM E2 and thymus.

To further verify that estrogen-mediated apoptosis occurs through the Fas/FasL pathway, pre-osteoclasts were differentiated from the bone marrow from FasL-deficient mice (gld) and Fas-deficient mice (lpr). Mice carrying either the gld or the lpr mutation suffer from lymphadenopathy and autoimmune disease due to the loss-of-function point mutations in FasL and Fas (Cohen and Eisenberg, 1991; Takahashi et al, 1994). Bone marrow-derived cells from gld and lpr mice were differentiated to the pre-osteoclast stage, and then treated with 10 nM E2 for 16 h. Whereas pre-osteoclasts from wild-type mice were apoptotic after E2 treatment, pre-osteoclasts from FasL- and Fas-deficient mice failed to undergo apoptosis (Figure 2B). This provides genetic evidence that the Fas/FasL pathway is necessary for estrogen-induced apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts.

To determine if the Fas/FasL pathway is transcriptionally activated by E2 in osteoclasts, we analyzed both Fas and FasL mRNA levels. RNA was obtained from bone marrow stroma, pre-osteoclasts and osteoclasts, and Fas mRNA levels were measured by quantitative real-time PCR and compared to the level in the thymus as a positive control. Detectable levels of Fas were found in pre-osteoclasts; however, Fas mRNA did not increase after E2 treatment of pre-osteoclasts or osteoclasts (Figure 2C). Likewise, FasL mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real-time PCR in pre-osteoclasts and osteoclasts, and the levels of FasL were also not increased by E2 in these cells (Figure 2D). Thus while Fas/FasL signaling is required for the E2-induced apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts, the levels of neither were directly regulated by E2 in this cell type.

Estrogen induces FasL transcription in osteoblasts

As we could find no evidence for the estrogen regulation of Fas or FasL in osteoclasts, we hypothesized that a second bone cell type, namely osteoblasts, might play a role in the induction of apoptosis in osteoclasts. To this end, osteoblasts were tested for the induction of FasL mRNA. Primary calvarial osteoblasts were obtained from neonatal mice. Throughout the differentiation process of osteoblasts, E2 increased the levels of FasL mRNA in these cells. E2 increased FasL mRNA by approximately three-fold early in differentiation and by five-fold in fully differentiated osteoblasts (Figure 3A). This result was confirmed in the mouse calvarial pre-osteoblast cell line MC3T3 that was differentiated into mature osteoblasts by treatment with ascorbic acid for 10 days. In differentiated MC3T3 cells, FasL mRNA levels increased three-fold in the presence of E2 (Figure 3E).

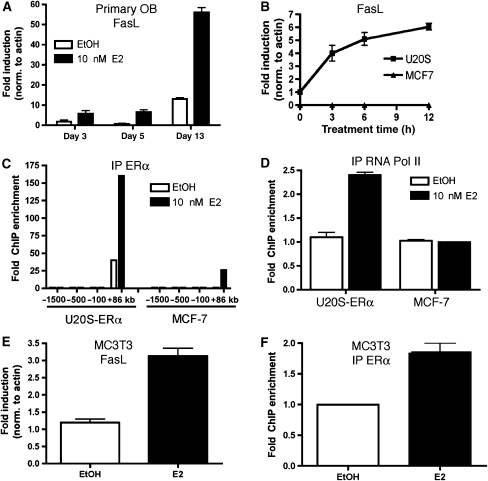

Figure 3.

Estrogen increases FasL in osteoblasts. (A) Primary calvarial osteoblasts were differentiated for 3, 5 or 13 days in the presence of 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid and 5 mM β-glycerophosphate. Cells were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 3 h and RNA was obtained. FasL mRNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR. (B) U20S-ERα and MCF-7 cells were deprived of estrogen for 3 days in phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS. They were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 0, 3, 6 or 12 h and RNA was obtained. FasL mRNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR. (C) U20S-ERα cells and MCF-7 cells were deprived of estrogen for 3 days in phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS. They were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 45 min. ERα (C) and RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) (D) were immunoprecipitated, DNA was isolated and quantitative PCR was performed at the indicated sites of the FasL locus. Each PCR signal was normalized to input. (E) MC3T3 cells were differentiated for 10 days in the presence of 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid. The media were then changed to phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS for 3 days. The cells were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 3 h and FasL mRNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR. (F) MC3T3 cells were differentiated for 10 days in the presence of 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid. The media were then changed to phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS for 3 days. The cells were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 45 min. ERα was immunoprecipitated, DNA was isolated and quantitative PCR was performed with primers for the FasL enhancer. Each PCR signal was normalized to input. Error bars in all panels represent ±1 s.d.

To further characterize the regulation of FasL by E2, the osteoblast-like U20S-ERα cell line and control MCF-7 breast cancer cell line were also treated with E2 to determine if FasL levels were increased. The U20S-ERα cell line is an osteosarcoma cell line that was stably transfected with doxycycline-inducible expression of ERα. Upon treatment with doxycycline, the expression of ERα in U20S-ERα cells is similar to MCF-7 cells (Monroe et al, 2003). Whereas MCF-7 cells had no detectable levels of FasL by quantitative real-time PCR, E2 increased the mRNA levels of FasL in the U20S-ERα cell line (Figure 3B), indicating that E2 induction of FasL is osteoblast specific.

To understand the mechanism by which estrogen specifically upregulates FasL mRNA in osteoblasts, we sought to identify whether FasL is a direct ERα target gene. Our previous work defining authentic ERα binding sites across the whole human genome in MCF-7 cells by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) on whole genome tiling arrays (Carroll et al, 2006) identified a potential site near the FasL gene. This binding site, located 86 kilobases (+86 kb) telomeric of the FasL coding region, contains a well-conserved estrogen response element (Supplementary Figure 4). We have previously shown that ER binding sites are often distant and downstream of the transcription start sites of target genes (Carroll et al, 2005). In addition, the nearest gene telomeric to this ERα binding site is TNFSF18, which is 265 kb away from the site and is not regulated by E2 in U20S-ERα cells nor in MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Figure 4; data not shown). To test whether the ERα binding site 86 kb downstream of the FasL transcription start site was bound in osteoblast-like cells, we conducted directed ChIP for ERα in MCF-7 and U20S-ERα cells. As predicted from our previous study, ERα levels were enriched at the +86 kb site in MCF-7 cells. Strikingly, both the basal and E2-induced binding levels were very significantly greater in U20S-ERα cells compared to MCF-7 (Figure 3C). Although there is recruitment of ERα to this region in MCF-7 cells, recruitment of ERα to DNA is in many cases not sufficient for gene activation (Carroll et al, 2006). Consistent with the pattern of FasL gene expression, RNA polymerase II is not recruited to the promoter of FasL in MCF-7 cells, but it is recruited in U20S-ERα cells following estrogen stimulation (Figure 3D).

To confirm that ERα is recruited to the putative FasL enhancer in osteoblasts, we performed directed ChIP in the MC3T3 cells that had been differentiated for 10 days with ascorbic acid. ERα was detectable at the FasL enhancer, increasing almost two-fold after treatment with E2 (Figure 3F). These results support the conclusion that FasL is a direct ERα target gene in osteoblasts and that this regulation involves a cell-type-specific estrogen-stimulated enhancer located 86 kb downstream of the FasL coding region.

FasL is induced in osteoblasts by E2 in vitro

To determine which cells express Fas and FasL in the mixed bone cell cultures, murine bone marrow cells were differentiated with RANKL and M-CSF, and then the cells were fixed and immunostained. First, osteoblasts were identified by alkaline phosphatase staining (Figure 4A) and then co-stained for Fas. The osteoblasts did not stain positive for Fas, but all of the remaining cells were positive for Fas. In addition, Fas expression was frequently clustered on the side of the osteoclast adjacent to neighboring osteoblasts, indicative of Fas activation (Figure 4A, inset).

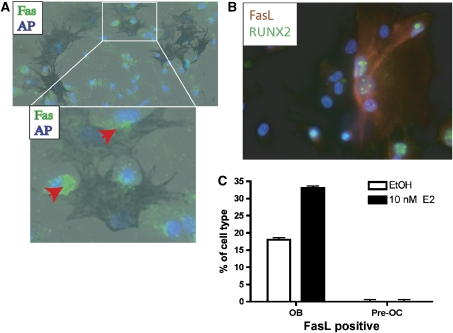

Figure 4.

Fas is expressed in pre-osteoclasts and FasL is expressed in osteoblasts. (A) Bone marrow cultures treated under osteoclastic conditions for 6 days to the pre-osteoclast stage were fixed and immunostained for Fas. The primary antibody was detected with an anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 488 (green fluorescence). DNA was counterstained with DAPI. The cells were then stained for alkaline phosphatase (dark blue cells). The red arrowhead points to clustering of the Fas receptor proteins next to the osteoblast. Parallel cultures were stained with TRAP to identify pre-osteoclasts. (B) Bone marrow cultures treated under osteoclastic conditions for 6 days to the pre-osteoclast stage were fixed and immunostained for FasL and RUNX2. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. (C) A laser scanning cytometer was used to separate cells with low and high RUNX2. The amount of FasL in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2 was quantified in each of these populations.

Second, to characterize FasL-expressing cells, bone marrow cells were differentiated with RANKL and M-CSF and immunostained with antibodies to FasL and RUNX2. Immunofluorescent microscopy showed that the majority of the cells are positive for 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) only (Figure 4B). Osteoblast cells, marked by the expression of RUNX2, were also positive for FasL (Figure 4B). We performed laser scanning cytometry (LSC) analysis on these samples to quantify the percentage of cells that were positive for RUNX2 and/or FasL in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2. The data indicate that only 3% of the total cells are osteoblasts and the amount of RUNX2 did not change in the presence of E2 (Supplementary Figure 5). When we determined the number of RUNX2/FasL double positive cells, 17% of the untreated osteoblasts were positive for RUNX2 and FasL. Upon treatment with E2, 35% of the osteoblasts were positive for both RUNX2 and FasL (Figure 4C), suggesting that in mixed bone cultures in vitro, osteoblasts and not osteoclasts are the cells in which FasL is expressed and estrogen-regulated.

FasL is induced by E2 in vivo

In order to confirm that estrogen activates FasL in osteoblasts in vivo, sham-operated and ovariectomized mice were treated with vehicle or 50 μg/kg body weight of E2 for 24 h. Femurs from ovariectomized mice had significantly higher TRAP staining (Supplementary Figure 6) than in sham-operated mice, indicating an increase in the number of osteoclasts due to the absence of estrogen and lack of estrogen-induced apoptosis. FasL was localized by immunohistochemisty before and after treatment with E2. FasL was not observed in the femurs from untreated animals, but FasL could be identified at the endosteal surface (Figure 5A and C) and at the growth plate (Figure 5B) in femurs from E2-treated mice.

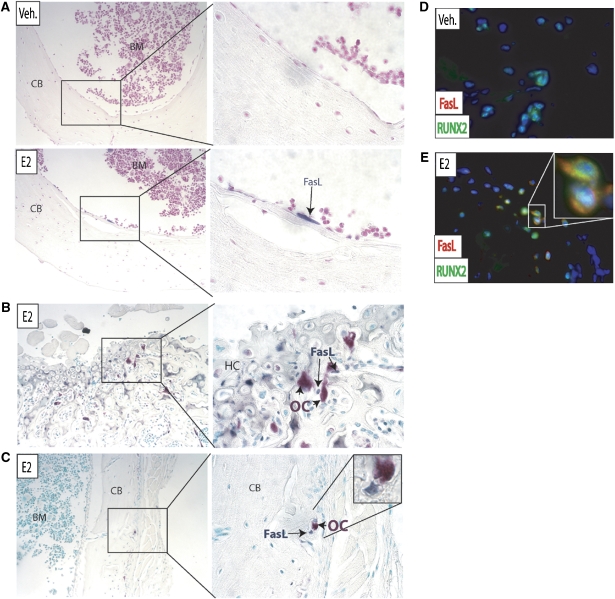

Figure 5.

FasL is induced by E2 in osteoblasts in vivo. (A) Ovariectomized mice were treated with either vehicle (veh.) or 50 μg/kg E2 for 24 h. Paraffin-imbedded femurs were immunostained with an antibody to FasL (blue) and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (pink). BM=bone marrow, CB=cortical bone. (B) The growth plate and (C) diaphysis of E2-treated femurs were immunostained with FasL (blue) and osteoclasts were identified with TRAP (pink). HC=hypertrophic chondrocytes. The cells were counterstained with a nuclear green dye (methyl green). (D) Femurs treated with vehicle alone (veh.) or (E) E2 were immunostained for FasL (red) and RUNX2 (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue).

To directly confirm that FasL-positive cells were indeed osteoblasts, immunofluorescence for the osteoblast-specific RUNX2 and FasL was performed on femurs from control and E2-treated mice. Osteoblasts (identified by RUNX2 staining) from vehicle-treated mice were negative for FasL (Figure 5D). After treatment with E2, FasL-positive staining was visualized in osteoblasts (Figure 5E). Furthermore, these FasL-positive osteoblasts were next to TRAP-positive osteoclasts at both the growth plate (Figure 5B) and in the diaphysis (Figure 5C).

Apoptosis of osteoclasts by estradiol is mediated by ERα

To test whether E2-induced apoptosis was mediated by nuclear ERs, mixed bone marrow cultures were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days, followed by treatment with E2 and the pure ER-antagonist fulvestrant (ICI), alone or in combination. Fulvestrant alone did not cause apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts, but it was able to block E2-mediated apoptosis, indicating involvement of the classical nuclear ER pathway (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Apoptosis of pre-osteoclasts is mediated by ERα. (A) Pre-osteoclasts were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days and then treated for 16 h with vehicle control (ethanol, EtOH), 1 nM E2 and/or 10 nM ICI 182,780 (ICI). Cells were fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Quantification was performed with a laser scanning cytometer (LSC). (B) Bone marrow cells from wild-type (WT), ERαKO or ERβKO mice were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2 to the pre-osteoclast stage. Cells were then fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Quantification was performed with a laser scanning cytometer (LSC). (C) Bone marrow cells from wild-type (WT), ERαKO or ERβKO mice were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL in the presence or absence of 10 nM E2 for 8 days. Cells were then fixed and stained for TRAP. Multinucleated cells, defined as cells that are TRAP positive and containing three or more nuclei, were counted in each well. Three wells were counted for each genotype. (D) Bone marrow cells from wild-type and ERαKO mice were cultured in mesenchymal stem cell media and then differentiated under osteoblastic conditions for 9 days. mRNA for FasL was measured by quantitative PCR. (E) U20S-ERβ cells were deprived of estrogen for 3 days in phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS. They were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 3 h and RNA was obtained. FasL and Rbbp1 mRNA levels were analyzed by quantitative PCR. (F) U20S-ERβ cells were deprived of estrogen for 3 days in phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS. They were then treated with 10 nM E2 for 45 min. An anti-Flag antibody was used to immunoprecipitate ERβ and quantitative PCR was performed to detect the Rbbp1 enhancer or the FasL enhancer (+86 kb site). Each PCR was normalized to input.

To determine the contribution of ERα versus ERβ in E2-induced apoptosis, bone marrow was obtained from ERα knockout (ERαKO), ERβ knockout (ERβKO) and ERα/ERβ double knockout (ERαβKO) mice. Bone marrow cells from wild-type, ERαKO, ERβKO and ERαβKO mice all formed TRAP-positive osteoclasts (Supplementary Figure 7). Pre-osteoclasts from wild-type C57BL/6 mice and ERβKO mice were TUNEL positive after a 16 h exposure to E2. However, ERαKO (and ERαβKO) osteoclasts failed to undergo apoptosis when treated with 10 nM E2 (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure 7). As a result, there were as many TRAP-positive, multinucleated osteoclasts in ERαKO cultures treated with E2 as in vehicle control-treated cultures (Figure 6C).

As E2 induces FasL via ERα, we hypothesized that FasL levels would be lower in osteoblasts from ERαKO mice. Bone marrow cells were cultured in mesenchymal stem cell media and then differentiated to osteoblasts with ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate. The FasL mRNA levels were 10-fold lower in ERαKO cells when compared to the wild-type osteoblasts (Figure 6D).

To further confirm that activation of ERβ did not play a role in pre-osteoclast apoptosis, we tested for the induction of FasL in U20S-ERβ cells. The U20S-ERβ cell line, like the U20S-ERα cell line, is derived from the parental U20S cells, but it is stably transfected with doxycycline-inducible ERβ cDNA. Whereas E2 led to the induction of FasL in U20S-ERα cells (Figure 3B), FasL mRNA was unchanged in the U20S-ERβ cells (Figure 6E), while a positive control ERβ target gene, retinoblastoma binding protein 1 (Rbbp1), (Monroe et al, 2006) was induced by ERβ in the presence of E2 (Figure 6E). Consistent with the expression results, E2 did not induce recruitment of ERβ to the +86 kb ERα binding site (Figure 6F). The Rbbp1 enhancer was used as a positive control for ERβ binding (Monroe et al, 2006). Taken together, these data demonstrate that E2 mediates osteoblast-dependent pre-osteoclast apoptosis via ERα and not ERβ.

ERα in osteoblasts is sufficient for E2-mediated apoptosis

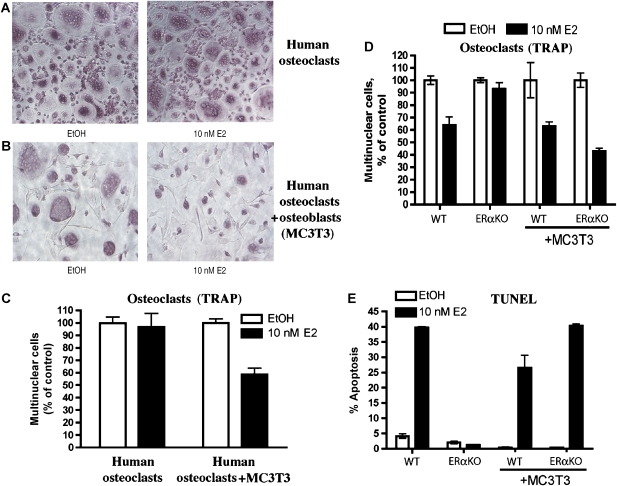

To confirm that osteoblasts are required for estrogen-induced apoptosis of human osteoclasts, antibody-purified monocytes from peripheral blood obtained from blood donors were used to produce osteoclasts. Large, multinucleated, TRAP-positive cells formed in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF after 8 days (Figure 7A). Alkaline phosphatase-positive osteoblasts could not be detected in these cultures. When 10 nM E2 was added to the culture media, during the entire course of differentiation no apoptosis occurred, and osteoclasts differentiated into equivalent numbers of large-multinucleated, TRAP-positive cells (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Osteoblasts are required for estrogen-mediated apoptosis. (A) Human monocytes were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL to osteoclasts, without or (B) with osteoblasts (MC3T3 cells), and (left) without or (right) with 10 nM E2 for 8 days. The cells were then fixed and stained for TRAP. (C) The number of multinucleated cells per field from (A) and (B) was counted and expressed as a percentage of the vehicle control-treated cells. Each treatment was counted in triplicate and error bars represent ±1 s.d. (D) Bone marrow cells from wild-type or ERαKO mice were co-cultured with or without MC3T3 cells and without or with 10 nM E2 under osteoclastic conditions for 8 days. The cells were then fixed and stained for TRAP. The number of multinucleated cells per field was counted and expressed as a percentage of the vehicle control-treated cells. (E) Cells were cultured as in part D, except that 10 nM E2 was added at day 6 for 16 h. The cells were then fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Quantification was performed with a laser scanning cytometer.

A co-culture system was established to demonstrate the dependence on osteoblasts for the induction of apoptosis in human osteoclasts. MC3T3 osteoblast cells were incubated for 8 days in the presence of purified human monocytes. In the absence of E2, fully differentiated osteoclasts formed in the presence of MC3T3 osteoblasts (Figure 7B, left panel). When 10 nM E2 was added to the co-culture during the entire course of differentiation, there were fewer multinucleated, TRAP-positive cells and the TRAP-positive cells were smaller in diameter and had fewer nuclei per cell (Figure 7B, right panel). Quantification of the number of multinucleated cells in each condition shows that only in the presence of osteoblasts there is an E2-mediated decrease in osteoclast number (Figure 7C). These results demonstrate that osteoblasts are required for the E2 induction of osteoclast cell death.

To demonstrate that expression of ERα in osteoblasts is sufficient to induce apoptosis of osteoclasts, MC3T3 cells were co-cultured with either wild-type or ERαKO bone marrow under osteoclast growth conditions that we previously showed contains a minority of osteoblasts as well. The number of wild-type TRAP-positive, multinucleated osteoclasts decreased in the presence of E2 with or without the addition of MC3T3 cells (Figure 7D). In contrast, the number of mature osteoclasts from ERαKO mice decreased only in the presence of MC3T3 osteoblasts and E2 (Figure 7D). To confirm that apoptosis was responsible for the reduction in mature osteoclast numbers, TUNEL assays were performed in parallel. Bone marrow-derived wild-type osteoclasts were TUNEL positive in the presence of E2, with or without MC3T3 osteoblasts (Figure 7E and Supplementary Figure 8). In striking contrast, ERαKO-derived osteoclasts underwent E2-mediated apoptosis only in the presence of MC3T3 osteoblasts (Figure 7E and Supplementary Figure 8). These results confirm that expression of ERα in osteoblasts is sufficient to induce estrogen-stimulated apoptosis of osteoclasts.

SERMs also upregulate FasL in osteoblasts to induce apoptosis

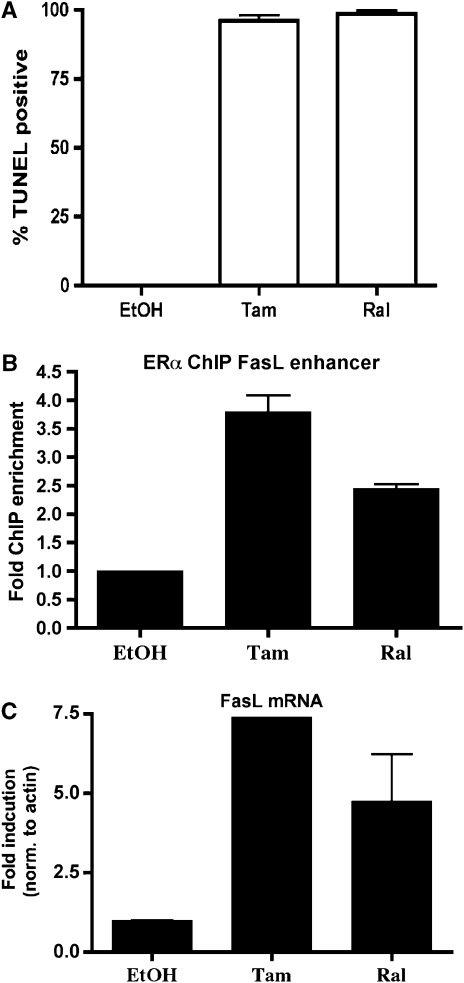

As SERMs are clinically important in the treatment of osteoporosis, we sought to determine if SERMs could induce apoptosis by the same mechanism as E2. Bone marrow cultures were treated with either 4-hydroxytamoxifen (tam) or raloxifene (ral). Following treatment with either SERM, nearly 100% of pre-osteoclasts were apoptotic after 16 h (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

SERMs regulate FasL to induce apoptosis. (A) Pre-osteoclasts were differentiated with M-CSF and RANKL and then treated for 16 h with vehicle (EtOH), 1 μM tam or 10 nM ral. Cells were fixed and apoptosis was detected by TUNEL. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) U20S-ERα cells were deprived of estrogen for 3 days in phenol red-free media containing 5% CDT-FBS. Cells were then treated for 45 min with 1 μM tam or 10 nM ral. ChIP was performed with an antibody to ERα and quantitative PCR was performed to detect the FasL enhancer (+86 kb site). Each PCR was normalized to input. (C) Cells were deprived of estrogen as in part B. They were then treated with 1 μM tam or 10 nM ral for 3 h and RNA was obtained. FasL mRNA was analyzed by quantitative PCR. Error bars represent ±1 s.d.

To determine if tam and ral upregulate FasL by the same mechanism as does E2, ChIP was performed after treating U20S-ERα cells with tam or ral for 45 min. Both tam and ral lead to the recruitment of ERα to the FasL enhancer (Figure 8B) to a similar extent as E2 (Figure 3C). Furthermore, quantitative PCR showed that tam and ral are each capable of inducing FasL mRNA (Figure 8C). These data taken together suggest that tam and ral are capable of inducing apoptosis in pre-osteoclasts via upregulation of FasL in osteoblasts.

Discussion

An understanding of the mechanism of protective effects of estrogen and SERMs in bone has very important implications for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Previous work by others has shown that a significant part of this effect comes from the ability of estrogen to induce osteoclast apoptosis. Recent work from Nakamura et al (2007) suggests a direct role of ERα in osteoclasts and that estrogen-induced apoptosis of osteoclasts involves FasL-mediated cell suicide. We have explored the mechanistic basis for the ability of estrogen to induce osteoclast apoptosis and in contrast to the findings of Nakamura and colleagues we find a critical role of osteoblasts in FasL-mediated killing of pre-osteoclasts. In cell culture and in vivo, we find that estrogen induces FasL expression in osteoblasts and not in osteoclasts. Furthermore, antibody-purified osteoclasts do not undergo estrogen-induced apoptosis unless osteoblasts are added in a co-culture system. Furthermore, co-cultures of osteoblasts and ERαKO bone marrow-derived osteoclasts demonstrate that ERα in osteoblasts is sufficient for osteoclast apoptosis. In addition, we have identified a cell-type-specific estrogen-regulated enhancer some 86 kb downstream of the FasL coding region that is active in osteoblasts, confirming the direct regulation of FasL by ERα in this cell type.

Bone remodeling is a complex interaction between many cell types; osteoblasts and osteoclasts are regulated both by each other and by cells in the bone marrow, such as T cells and dendritic cells (Clowes et al, 2005). Osteoblasts and bone marrow stromal cells express both RANKL, to differentiate osteoclasts, and osteoprotegerin, to inhibit osteoclast differentiation. Furthermore, bidirectional signaling between osteoclasts and osteoblasts has been described for ephrins and ephrin receptors, illustrating the importance of cell-to-cell cross talk in the regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation and survival (Zhao et al, 2006).

The etiology of osteoporosis is multifactorial, including a genetic component. Between 50 and 85% of bone mass is thought to be genetically determined (Ralston and de Crombrugghe, 2006). To date, no studies on the role of Fas or FasL polymorphisms or mutations in osteoporosis have been done. However, Fas mutant mice (lpr mice) and FasL mutant mice (gld mice) have an increase in the number of osteoclasts and a decrease in bone mineral density (Wu et al, 2003). We have demonstrated that pre-osteoclasts from gld and lpr mice fail to undergo estrogen-induced apoptosis, which would lead to the observed phenotype of these mice. In addition, while post-menopausal estrogen levels and polymorphisms in ERα have been linked to the risk of osteoporosis, no studies to date have explored the possibility of polymorphisms in the cis-regulatory targets of ERα. The identification of the ERα-dependent enhancer of FasL suggests a possible site to explore as a cause of phenotypic variation in the population with regard to osteoporosis risk.

Estrogen deficiency has been associated with an increase in cytokines that enhance osteoclast differentiation. There is a complex balance between the immune system, osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and estrogen regulates many of these regulatory factors. These cytokines include IL-1, IL-6, M-CSF, RANKL and TNF-α (reviewed in Zallone, 2006). A change in these cytokines may prime the pre-osteoclast for estrogen-mediated apoptosis by FasL and explain the requirement for ERα expression in osteoclasts, as suggested by Nakamura et al. Further studies exploring the direct ERα-dependent targets in osteoclasts should help shed light on the cell-autonomous role of estrogen in this cell type.

In conclusion, these experiments identify a critical paracrine signal emanating from osteoblasts that plays an important role in the protective effects of estrogen in bone. The finding that existing SERMs such as tam and ral that have beneficial effects on bone exploit the same mechanism should facilitate the development of new therapies that retain this activity and eliminate the unwanted menopausal side effects of existing SERMs.

Materials and methods

Reagents

E2, tam and doxycycline were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. ICI 182,780 was generously provided by Astra-Zeneca. Charcoal-dextran-treated fetal bovine serum (CDT-FBS) was purchased from Omega Scientific. RANKL and M-CSF were purchased from R&D Systems. TRAP and alkaline phosphatase stains were obtained from Takara Bio Inc. The following antibodies were used: FasL (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., N-20; and R&D Systems, 101626), Fas (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., A-20), RUNX2 (R&D Systems, 232902), ERα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., HC-20; and Lab Vision Corporation, Ab-10), RNA polymerase II (Abcam, 8WG16) and Flag (Sigma-Aldrich Co., M2). Goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488, donkey anti-goat Alexa 488 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa 594 were purchased from Invitrogen Corporation.

Animals

All animal work was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Seven-week-old male BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories Inc. No difference in apoptosis was observed between male and female mice (Kousteni et al, 2002), but male mice were used consistently for in vitro experiments. ERα, ERβ and ERαβ knockout mice were kindly provided by Dr Pierre Chambon (Dupont et al, 2000). Wild-type (C57BL/6) littermates were used as controls. FasL knockout mice (B6Smn.C3-Faslgld/J) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, along with age-matched wild-type controls (C57BL/6Smn). Fas knockout mice (C3.MRL-Faslpr/J) were also obtained from Jackson Laboratories, along with age-matched wild-type controls.

Ovariectomy and in vivo estrogen treatment

Six-week-old sham or ovariectomized BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River. Two weeks after surgery, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 μg/kg body weight of E2 or sesame oil (as a vehicle control) for 24 h (Kobayashi et al, 2006). The femurs were snap frozen in 7% gelatin and 4 μm sections were made using the CryoJane tape transfer system or fixed in 4% PFA, decalcified and paraffin embedded. TRAP staining of femurs was performed to verify ovariectomy (Supplementary Figure 6). In addition, the uterus was collected to verify ovariectomy and estrogen treatment.

Cell culture

MCF-7 cells and MC3T3-E1 cells were obtained from ATCC. U20S-ERα cells and U20S-ERβ cells, kindly provided by Dr Thomas Spelsberg, were maintained as described (Monroe et al, 2003). At 24 h before treatment with E2, ER expression in U20S-ERα or U20S-ERβ cells was induced by treatment with 100 ng/ml doxycycline.

Osteoclast formation

Bone marrow was isolated from the femur and tibia of mice. Osteoclasts were obtained as described (Takahashi et al, 2003). Human osteoclasts were differentiated as follows: leukocytes were obtained from the apheresis by-product of platelet donations at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA. Monocytes were purified by negative selection using the Monocyte Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) and plated in αMEM with 10 ng/ml M-CSF and 30 ng/ml RANKL for 8 days. TRAP and alkaline phosphatase staining were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Osteoblast differentiation

Primary osteoblasts were obtained from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (from wild type or ERαKO) or the calvaria of wild-type mice. Bone marrow was incubated for 5 days in mesenchymal stem cell media (MesenCult Basal Media, StemCell Technologies Inc.), followed by differentiation in 5 mM β-glycerophosphate and 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid (mineralization medium) for 9 days. Neonatal BALB/c calvaria were obtained 2 days after birth and incubated for 40 min in αMEM–1.0 mg/ml collagenase P–1.25% trypsin at 37°C. These were washed in αMEM and transferred to αMEM–1.0 mg/ml collagenase P–1.25% trypsin for 1 h at 37°C (Ducy et al, 1999). Digestion was stopped by the addition of αMEM/10% FBS. The cells from the second digest were allowed to attach for 48 h and then differentiated in mineralization medium with media replacement every 3 days. Differentiation was confirmed by quantification of bone sialoprotein and osteocalcin mRNA, alkaline phosphatase positivity and Von Kossa staining for mineralization. MC3T3 cells were maintained in αMEM without ascorbic acid. For differentiated cells, MC3T3 cells were allowed to reach confluence (day 0). Cells were then treated with 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid for 10 days.

Co-culture of osteoclasts and osteoblasts

Hundred MC3T3 cells were plated in each well of a 96-well plate. The following day, 100 000 human monocytes (purified as described above) or 100 000 murine bone marrow cells (from wild-type or ERαKO mice) were plated with the attached MC3T3 cells. The monocytes and MC3T3 cells were cultured for 8 days with or without 10 nM E2 in αMEM with 10 ng/ml M-CSF, 30 ng/ml RANKL, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate and 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid, then fixed and stained for TRAP or TUNEL.

Apoptosis

Differentiated pre-osteoclast cultures were treated with E2 for 7–24 h as described in each figure legend. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and TUNEL assays (Roche Applied Sciences) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Apoptosis was quantified using a laser scanning cytometer (CompuCyte Corporation). Cells were counterstained with DAPI to visualize DNA. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and a representative experiment is shown.

FasL inhibition

Pre-osteoclasts were differentiated for 6 days in the presence of 10 ng/ml M-CSF and 30 ng/ml RANKL. On the sixth day, the media were changed to 5% CDT-FBS-containing αMEM with M-CSF and RANKL but without phenol red. After 24 h, cells were treated with or without 10 nM E2, and with 5 ng/ml rat anti-mouse FasL from R&D Systems or control IgG to inhibit FasL.

RNA and real-time PCR

Total RNA was converted to cDNA using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen Corporation). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. cDNA was subjected to quantitative PCR using the Applied Biosystems SYBR Green Mastermix. Each RNA sample was collected in triplicate and each PCR was amplified in triplicate. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation (s.d.).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Cells were hormone-deprived by culture for 3 days in phenol red-free medium (Invitrogen Corporation) supplemented with 5% CDT-FBS. Cells were challenged with hormone for 45 min and ChIP was performed as described (Carroll et al, 2005; Eeckhoute et al, 2006). Each ChIP was performed in triplicate and each PCR was amplified in triplicate (Eeckhoute et al, 2007). Data are presented as mean and s.d.

Immunofluorescence and laser scanning cytometry

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min on ice and incubated overnight in blocking buffer (1 × TBST, 3% BSA, 1% normal goat or donkey serum, 0.2% sodium azide, 1% Triton X-100). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight and analyzed with a laser scanning cytometer (CompuCyte) and immunofluorescence microscopy. Goat anti-rabbit Alexa 488, donkey anti-goat Alexa 488 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa 594, all ‘highly crossed-absorbed' (Molecular Probes), were used to detect the primary antibody. Cells were counterstained with DAPI in mounting medium (Vector Laboratories Inc.) to identify nuclei. The UV fluorescence emission (>463 nm) was used to contour DAPI-stained nuclei with a minimum cell area of 20 μm (first pass). The argon laser (488 nm) was used to identify FITC conjugation (second pass) and the long red fluorescence emission (>650 nm; third pass) was excited by the He–Ne laser (633 nm). Threshold values of 4000 were used to contour second and third pass and set to reject cell clusters >1000 μm2. Eleven pixels were added from DAPI to threshold to contour cytoplasmic area. For fluorescence microscopy, a Leica DM IRBE fluorescent microscope using × 10 and × 63 objectives (Leica Microsystems) and Openlab software (Improvision) was used for image acquisition. LSC analysis was performed using WinCyte software (CompuCyte).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the Susan G Komen Breast Cancer Foundation to SAK. This work was also supported in part by a grant from Wyeth. We thank all the members of the Brown lab for their helpful discussions and review of the manuscript.

References

- Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, Fox EA, Silver PA, Brown M (2005) Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell 122: 33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger TR, Eeckhoute J, Brodsky AS, Keeton EK, Fertuck KC, Hall GF, Wang Q, Bekiranov S, Sementchenko V, Fox EA, Silver PA, Gingeras TR, Liu XS, Brown M (2006) Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet 38: 1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes JA, Riggs BL, Khosla S (2005) The role of the immune system in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Immunol Rev 208: 207–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen PL, Eisenberg RA (1991) Lpr and gld: single gene models of systemic autoimmunity and lymphoproliferative disease. Annu Rev Immunol 9: 243–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke PS, Naaz A (2004) Role of estrogens in adipocyte development and function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 229: 1127–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M, Sulli A, Capellino S, Villaggio B, Montagna P, Seriolo B, Straub RH (2004) Sex hormones influence on the immune system: basic and clinical aspects in autoimmunity. Lupus 13: 635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutter WJ, Craig M, Norbury R, Robertson DM, Whitehead M, Murphy DG (2003) In vivo effects of estrogen on human brain. Ann NY Acad Sci 1007: 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Starbuck M, Priemel M, Shen J, Pinero G, Geoffroy V, Amling M, Karsenty G (1999) A Cbfa1-dependent genetic pathway controls bone formation beyond embryonic development. Genes Dev 13: 1025–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Krust A, Gansmuller A, Dierich A, Chambon P, Mark M (2000) Effect of single and compound knockouts of estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta) on mouse reproductive phenotypes. Development 127: 4277–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastell R (2006) Pathogenesis of postmenopausal osteoporosis. In Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, Favus MJ (ed), pp 259–262. Washington, DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhoute J, Carroll JS, Geistlinger TR, Torres-Arzayus MI, Brown M (2006) A cell-type-specific transcriptional network required for estrogen regulation of cyclin D1 and cell cycle progression in breast cancer. Genes Dev 20: 2513–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhoute J, Keeton EK, Lupien M, Krum SA, Carroll JS, Brown M (2007) Positive cross-regulatory loop ties GATA-3 to estrogen receptor alpha expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res 67: 6477–6483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey CL, Fisher DE (2004) Mitf and Tfe3: members of a b-HLH-ZIP transcription factor family essential for osteoclast development and function. Bone 34: 689–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda T, Mano H, Yuasa T, Mori Y, Miyazawa K, Shiokawa M, Nakamaru Y, Hiroi E, Hiura K, Kameda A, Yang NN, Hakeda Y, Kumegawa M (1997) Estrogen inhibits bone resorption by directly inducing apoptosis of the bone-resorbing osteoclasts. J Exp Med 186: 489–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda N, Watanabe S (2004) 17beta-estradiol stimulates the growth of human keratinocytes by inducing cyclin D2 expression. J Invest Dermatol 123: 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Takahashi E, Miyagawa S, Watanabe H, Iguchi T (2006) Chromatin immunoprecipitation-mediated target identification proved aquaporin 5 is regulated directly by estrogen in the uterus. Genes Cells 11: 1133–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousteni S, Chen JR, Bellido T, Han L, Ali AA, O'Brien CA, Plotkin L, Fu Q, Mancino AT, Wen Y, Vertino AM, Powers CC, Stewart SA, Ebert R, Parfitt AM, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC (2002) Reversal of bone loss in mice by nongenotropic signaling of sex steroids. Science 298: 843–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe DG, Getz BJ, Johnsen SA, Riggs BL, Khosla S, Spelsberg TC (2003) Estrogen receptor isoform-specific regulation of endogenous gene expression in human osteoblastic cell lines expressing either ERalpha or ERbeta. J Cell Biochem 90: 315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe DG, Secreto FJ, Hawse JR, Subramaniam M, Khosla S, Spelsberg TC (2006) Estrogen receptor isoform-specific regulation of the retinoblastoma-binding protein 1 (RBBP1) gene: roles of AF1 and enhancer elements. J Biol Chem 281: 28596–28604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S, Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, Nishina H, Takeda S, Takayanagi H, Metzger D, Kanno J, Takaoka K, Martin TJ, Chambon P, Kato S (2007) Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor alpha and induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell 130: 811–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnemus U, Uenalan M, Conrad F, Handjiski B, Mecklenburg L, Nakamura M, Inzunza J, Gustafsson JA, Paus R (2005) Hair cycle control by estrogens: catagen induction via estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha is checked by ER beta signaling. Endocrinology 146: 1214–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikka V, Peng Z, Hentunen T, Risteli J, Elo T, Vaananen HK, Harkonen P (2005) Estrogen responsiveness of bone formation in vitro and altered bone phenotype in aged estrogen receptor-alpha-deficient male and female mice. Eur J Endocrinol 152: 301–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston SH, de Crombrugghe B (2006) Genetic regulation of bone mass and susceptibility to osteoporosis. Genes Dev 20: 2492–2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard DJ, Subramaniam M, Spelsberg TC (1999) Molecular and cellular mechanisms of estrogen action on the skeleton. J Cell Biochem 32–33 (Suppl): 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook P, Cooper C (2006) Osteoporosis. Lancet 367: 2010–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Boyd J, Frank GR, Takahashi H, Cohen RM, Specker B, Williams TC, Lubahn DB, Korach KS (1994) Estrogen resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a man. N Engl J Med 331: 1056–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen MG, Henriksen K, Dziegiel MH, Tanko LB, Karsdal MA (2006) Estrogen directly attenuates human osteoclastogenesis, but has no effect on resorption by mature osteoclasts. DNA Cell Biol 25: 475–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava RA, Srivastava N, Averna M, Lin RC, Korach KS, Lubahn DB, Schonfeld G (1997) Estrogen up-regulates apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene expression by increasing ApoE mRNA in the translating pool via the estrogen receptor alpha-mediated pathway. J Biol Chem 272: 33360–33366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Tanaka S, Suda T (2003) Generating murine osteoclasts from bone marrow. Methods Mol Med 80: 129–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Tanaka M, Brannan CI, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Suda T, Nagata S (1994) Generalized lymphoproliferative disease in mice, caused by a point mutation in the Fas ligand. Cell 76: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D (1975) Spleen cells transmit osteopetrosis in mice. Science 190: 785–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windahl SH, Andersson G, Gustafsson JA (2002) Elucidation of estrogen receptor function in bone with the use of mouse models. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13: 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski TJ, Dann LM, Scott KS, Cintron M (1989) Long-term effects of ovariectomy and aging on the rat skeleton. Calcif Tissue Int 45: 360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, McKenna MA, Feng X, Nagy TR, McDonald JM (2003) Osteoclast apoptosis: the role of Fas in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology 144: 5545–5555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallone A (2006) Direct and indirect estrogen actions on osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Ann NY Acad Sci 1068: 173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Irie N, Takada Y, Shimoda K, Miyamoto T, Nishiwaki T, Suda T, Matsuo K (2006) Bidirectional ephrinB2-EphB4 signaling controls bone homeostasis. Cell Metab 4: 111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data