Abstract

Background and purpose:

Gene expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is induced in activated hepatic stellate cells (HSC), the major effectors in hepatic fibrosis, and production of extracellular matrix (ECM) is consequently increased. We previously reported that curcumin, the yellow pigment in curry, suppressed ctgf expression, leading to decreased production of ECM by HSC. The purpose of this study is to evaluate signal transduction pathways involved in the curcumin suppression of ctgf expression in HSC.

Experimental approaches:

Transient transfection assays were performed to evaluate effects of activation of signalling pathways on the ctgf promoter activity. Real-time PCR and Western blotting analyses were conducted to determine expression of genes.

Results:

Suppression of ctgf expression by curcumin was dose-dependently reversed by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an NF-κB activator. LPS increased the abundance of CTGF and type I collagen in HSC in vitro. Activation of NF-κB by dominant active IκB kinase (IKK), or inhibition of NF-κB by dominant negative IκBα, caused the stimulation, or suppression of the ctgf promoter activity, respectively. Curcumin suppressed gene expression of Toll-like receptor-4, leading to the inhibition of NF-κB. On the other hand, interruption of ERK signalling by inhibitors or dominant negative ERK, like curcumin, reduced NF-κB activity and in ctgf expression. In contrast, the stimulation of ERK signalling by constitutively active ERK prevented the inhibitory effects of curcumin.

Conclusions and implications:

These results demonstrate that the interruption of NF-κB and ERK signalling by curcumin results in the suppression of ctgf expression in activated HSC in vitro.

Keywords: gene expression, hepatic fibrosis, hepatic stellate cell, polyphenol, signal transduction

Introduction

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), previously termed as fat- or vitamin A-storing cells, or Ito cells, are the effectors in hepatic fibrogenesis (Friedman, 2004; Kisseleva and Brenner, 2006). HSCs are quiescent and non-proliferative in the normal liver. Upon liver injury, quiescent HSCs become active, which is characterized by enhanced cell growth and overproduction of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. Culturing quiescent HSC on plastic plates causes spontaneous activation, mimicking the process seen in vivo, which provides a good model for elucidating underlying mechanisms of HSC activation and for studying possible therapeutic interventions in the process (Friedman, 2004; Kisseleva and Brenner, 2006). Although the causal relationship remains unclear, it has been demonstrated that activation of HSC is closely associated with activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) (Hellerbrand et al., 1998; Rippe et al., 1999). Inhibitor-κB (IκB) binds NF-κB and inhibits its activation by preventing NF-κB from translocating to the nucleus. Upon activation of NF-κB, IκBα is phosphorylated by IκB kinase (IKK), leading to the disassociation of IκBα from NF-κB and the subsequent degradation of IκBα.

There is a growing body of evidence that upregulation of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) might be a central pathway during HSC activation and hepatic fibrogenesis (Paradis et al., 1999; Williams et al., 2000). CTGF gene expression in HSC is significantly enhanced during the process of activation in vitro and in vivo (Williams et al., 2000). HSCs are the major cellular source of CTGF in the liver during hepatic fibrogenesis (Paradis et al., 2002). Gene expression of type I collagen is significantly induced by transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) during HSC activation. CTGF is transcriptionally regulated by TGF-β and plays a key role in the overproduction of ECM in activated HSC (Fu et al., 2001; Blom et al., 2002; Leask et al., 2003). Blockade of CTGF synthesis by antisense oligonucleotides of CTGF resulted in down expression of type I collagen mRNA in an animal model with experimental liver fibrosis (Uchio et al., 2004). The level of type I collagen has been used as a downstream target and a marker for evaluating the activity/expression of CTGF in cells (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Xiao et al., 2006).

Curcumin is the main yellow pigment in curry from turmeric. Besides its dietary use, curcumin has been used as an anti-inflammatory remedy in Chinese herbal medicine for skin and intestinal diseases and for wound healing. Recent studies have indicated that dietary administration of curcumin improves both acute and subacute rat liver injury caused by carbon tetrachloride (Park et al., 2000). We demonstrated previously that curcumin inhibited activation of HSC in vitro by inhibiting cell growth and suppressing production of ECM components (Xu et al., 2003). Curcumin induced gene expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and stimulated PPARγ signalling in activated HSC, which was a prerequisite for curcumin to inhibit HSC activation (Xu et al., 2003; Zheng and Chen, 2004). Our further studies demonstrated that curcumin suppressed gene expression of CTGF in activated HSC in vitro, leading to the reduction in the production of ECM components, including type I collagen and fibronectin (Zheng and Chen, 2006). The purpose of the present study was to investigate signal transduction pathways involved in the curcumin suppression of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC. Results presented in this study supported our hypothesis and demonstrated that the interruption of NF-κB and ERK signalling pathways by curcumin resulted in the suppression of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC. These results provide novel insights into the mechanisms of curcumin in the inhibition of HSC activation.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culture of HSCs

HSCs were isolated from male Sprague–Dawley rats (∼200–250 g) as described previously (Chen and Davis, 2000). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), unless otherwise indicated. HSCs between passages 4–8 were used for experiments. Curcumin cytotoxicity was evaluated previously (Xu et al., 2003). It was concluded that curcumin up to 100 μM was not toxic to cultured HSC. Curcumin at 20 μM was used in this study, unless otherwise indicated.

Western blotting analyses

These were performed as described previously (Xu et al., 2003). In brief, whole-cell lysates were prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation analyses buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Target proteins were detected by primary antibodies against CTGF (1:1000), αI(I) pro-collagen (1:500) or Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (1:1000), and subsequently by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Protein bands were visualized by using a chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Real-time PCR was carried out using SYBR Green as described previously (Chen et al., 2002; Fu et al., 2006). mRNA fold changes of target genes relative to the endogenous glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) control were calculated as suggested by Schmittgen et al. (2000). The following primers were used for real-time PCR: CTGF: (F) 5′-TGTGTGATGAGCCCAAGGAC-3′, (R) 5′-AGTTGGCTCGCATCATAGTTG-3′; TLR4: (F) 5′-TGGATACGTTTCCTTATAAG-3′, (R) 5′-GAAATGGAGGCACCCCTTC-3′; αI(I) collagen: (F) 5′-CCTCAAGGGCTCCAACGAG-3′, (R) 5′-TCAATCACTGTCTTGCCCCA-3′; GAPDH: (F) 5′-GGCAAATTCAACGGCACAGT-3′, (R) 5′-AGATGGTGATGGGCTTCCC-3′.

Plasmid constructs and transient transfection assays

The ctgf promoter luciferase reporter plasmid pCTGF-Luc, a gift from Dr Yuqing E Chen, (Cardiovascular Research Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GE, USA), contains a fragment of the ctgf promoter (∼2000 bp nucleotides) subcloned into the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3 (Fu et al., 2001). The NF-κB activity reporter plasmid pNF-κB-Luc was purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA). The plasmids pCMV-IKK-2 S177E/S181E and pCMV-IKK-2-WT were purchased from Addgene Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA). These two plasmids express the constitutively active form of IKK2 and wild-type IKK2, respectively. The plasmids pCMV-IκBα-WT, expressing wild-type IκBα, and pCMV-IκBα-M, encoding the dominant-negative form of IκBα (dn-IκBα), were purchased from Clontech. The plasmid pCMV-IκBα-M contains two serine to alanine mutations at residues 32 and 36, which prevents the phosphorylation of IκBα, leading to the blockade of NF-κB activation (Brown et al., 1995). The PPARγ cDNA-expressing plasmid pPPARγcDNA, containing a full size of PPARγ cDNA, was a gift from Dr Reed Graves (Department of Medicine, the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA). The plasmid pdn-ERK contains a full length of cDNA encoding the dominant-negative form of ERK. The plasmid pa-ERK contains cDNA encoding the constitutively active form of ERK (a-ERK). Both the plasmids were described previously (Davis et al., 1996). Transient transfection was conducted using LipofectAMINE (Life Technologies) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. In brief, semiconfluent HSC in six-well culture plates were transiently transfected with reporter plasmids (∼3–4 μg DNA per well). Transfection efficiency was controlled by co-transfection of the β-galactosidase reporter plasmid pSV-β (∼0.5–1 μg per well) (Promega Corp.). Luciferase activity was measured using an automated luminometer (Turners). β-Galactosidase assays were performed using an assay kit from Promega Corp. Each treatment was carried out in triplicate, in every experiment. Each experiment was repeated for at least three times. Luciferase activity was expressed as relative unit after normalization with β-galactosidase activity.

Statistical analysis

Differences between means were evaluated using an unpaired two-sided Student's t-test (P<0.05 considered as significant). Where appropriate, comparisons of multiple treatment conditions with controls were analysed by ANOVA with the Dunnett's test for post hoc analysis.

Materials

Curcumin (purity>94%), bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from E. coli and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate were purchased from Sigma. PD68235, a specific PPARγ antagonist, was kindly provided by Pfizer (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) (Camp et al., 2001).

Results

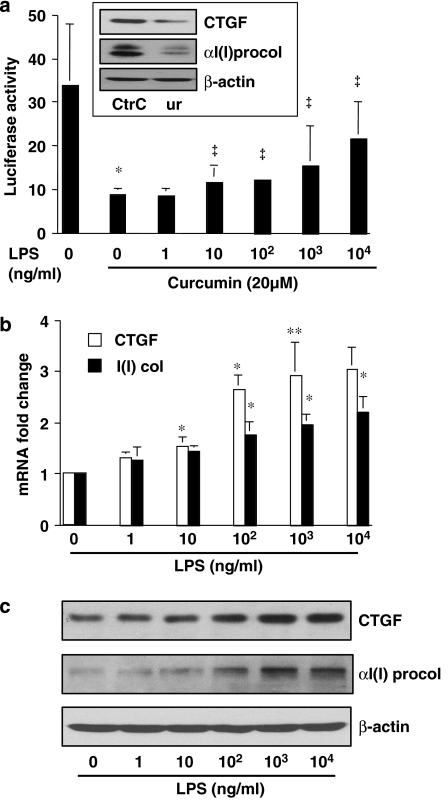

LPS dose-dependently abolishes the inhibitory effect of curcumin on the CTGF gene promoter and induces gene expression of CTGF and αI(I) collagen in activated HSC in vitro

Curcumin suppressed the ctgf promoter activity and reduced CTGF protein in HSC (Zheng and Chen, 2006). Curcumin also decreased the activity of NF-κB (Xu et al., 2003) in these cells. As bacterial LPS is an activator of NF-κB (Hacker and Karin, 2006), we hypothesized that the effects of curcumin on NF-κB and CTGF gene expression in our model might be antagonized by exposure to LPS.

Our pilot experiments confirmed that LPS dose-dependently increased the transactivation activity of NF-κB in cultured HSC (data not shown) and that curcumin reduced the abundance of CTGF and its downstream target αI(I)procollagen in cultured HSC (inset in Figure 1a). To test our hypothesis, passaged HSCs were transiently transfected with the ctgf promoter luciferase reporter plasmid pCTGF-Luc, containing a fragment of the CTGF gene promoter (∼2000 bp nucleotides) (Fu et al., 2001). After recovery, cells were treated with curcumin in the presence and absence of LPS at indicated concentrations for 24 h. As shown by luciferase assays in Figure 1a, curcumin, as expected, significantly reduced the ctgf promoter activity in these cells (the second column on the left), compared with that in the untreated control (the first column on the left). The inhibitory effect of curcumin was partially reversed by LPS exposure in a dose-dependent manner. Further experiments demonstrated that LPS increased the levels of the transcript and protein of CTGF and αI(I) procollagen in cultured HSCs, as shown by real-time PCR (Figure 1b) and western blotting analyses (Figure 1c), respectively. Taken together, these results suggested that the activation of NF-κB by LPS might induce gene expression of CTGF and partially reverse the inhibitory effect of curcumin on the ctgf promoter in activated HSC in vitro.

Figure 1.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) dose-dependently abolishes the inhibitory effect of curcumin on the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) gene promoter and induces gene expression of CTGF and αI(I) collagen in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. Passaged HSCs were treated with LPS at indicated concentrations for 24 h in the presence and absence of curcumin (20 μM). (a) Luciferase assays of cells transfected with the plasmid pCTGF-Luc. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative units after β-galactosidase normalization (n⩾6). *P<0.05 versus cells with no treatment (the first column on the left). ‡P<0.05 versus cells with curcumin only (the second column on the left). The inset demonstrates that curcumin (Cur) reduced the protein abundance of CTGF and αI(I) procollagen (αI(I) procol) analysed by western blotting analyses. (b) Real-time PCR analyses of the steady-state mRNA levels of CTGF and αI(I)collagen (αI(I) col). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an invariant control for calculating mRNA fold changes. Values are expressed as means±s.d. (n=3). *P<0.05, versus the untreated control (the corresponding first column on the left). (c) Western blotting analyses of the abundance of CTGF and αI(I)procollagen (αI(I) procol). β-Actin was used as an invariant control for equal loading. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown.

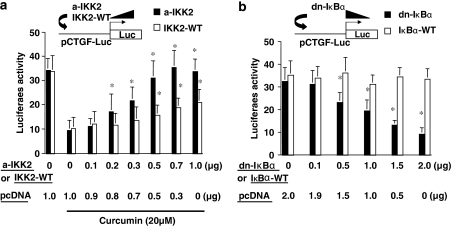

NF-κB activity plays a critical role in regulating the promoter activity of CTGF gene in activated HSC in vitro

Further experiments were conducted to directly evaluate the role of NF-κB activity in regulating the promoter activity of CTGF gene in activated HSC in vitro. Passaged HSCs were co-transfected with the ctgf promoter luciferase reporter plasmid pCTGF-Luc plus a cDNA expression plasmid pCMV-IKK-2 S177E/S181E (pa-IKK2) or pCMV-IKK-2-WT (pIKK2-WT). These two plasmids, respectively, express the constitutively active form of IKK2 or wild-type IKK2, leading to the induction of NF-κB activation. Prior transfection assays demonstrated that pa-IKK2 or pIKK2-WT enhanced NF-κB activity by approximately 20-fold or 1.5-fold, respectively (Yu et al., 2006). A total of 3.5 μg of plasmid DNA per well was used for co-transfection of HSC in six-well culture plates. It included 2 μg of pCTGF-Luc, 0.5 μg of pSV-β-gal and 1.0 μg of the cDNA expression plasmid at indicated doses plus the empty vector pcDNA. The latter was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After recovery, cells were treated with or without curcumin for 24 h. Results from luciferase assays demonstrated that the induction of NF-κB activation by overexpression of constitutively active form of IKK2 (a-IKK2), or wild-type IKK2 (IKK2-WT), dose-dependently eliminated the inhibitory effect of curcumin on the promoter activity of CTGF (Figure 2a). These results also showed that the IKK2-WT was relatively less effective, as expected (Yu et al., 2006). These results suggested that the activation of NF-κB might stimulate gene expression of CTGF in passaged HSC.

Figure 2.

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activity plays a critical role in regulating the promoter activity of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) gene in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. Passaged HSCs were co-transfected with the ctgf promoter luciferase reporter plasmid pCTGF-Luc plus a cDNA expression plasmid. A total of 3.5 μg (a) or 4.5 μg (b) of plasmid DNA per well was used for co-transfection of HSC in six-well culture plates. It included 2 μg of pCTGF-Luc, 0.5 μg of pSV-β-gal and 1.0 μg (a) or 2 μg (b) of the cDNA expression plasmid at indicated doses plus the empty vector pcDNA. The latter was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After recovery, cells were treated with or without curcumin for 24 h. Luciferase assays were performed. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative units after β-galactosidase normalization (means±s.d.; n⩾6). (a) Luciferase assays of cells co-transfected with pCMV-IKK-2 S177E/S181E (a-IKK2), encoding constitutively active form of IKK2, or with pCMV-IKK-2-WT (IKK2-WT), expressing wild-type IKK2. *P<0.05 versus cells transfected with no pa-IKK2 or pIKK2-WT, but treated with curcumin (the second column on the left). (b) Luciferase assays of cells co-transfected with pCMV-IκBα-M, encoding dominant-negative form of IκBα (dn-IκBα) or with pCMV-IκBα-WT encoding wild-type IκBα (IκBα-WT). *P<0.05 versus cells transfected with no dn-IκBα-M or IκBα-WT (the first column on the left).

To verify the role of NF-κB activity in regulating CTGF gene expression, passaged HSCs were similarly co-transfected with pCTGF-Luc plus another cDNA-expressing plasmid pCMV-IκBα-M or pCMV-IκBα-WT. The plasmid pCMV-IκBα-M encodes the dominant-negative form of IκBα (dn-IκBα), leading to the specific blockade of NF-κB activation (Brown et al., 1995). The plasmid pCMV-IκBα-WT expresses wild-type IκBα (IκBα-WT), which was used as a control. A total of 4.5 μg of plasmid DNA per well was used for co-transfection of HSC in six-well culture plates. It included 2 μg of pCTGF-Luc, 0.5 μg of pSV-β-gal and 2.0 μg of the cDNA expression plasmid at indicated doses plus the empty vector pcDNA. The latter was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After overnight recovery, cells were cultured for an additional 24 h. Luciferase assays demonstrated that forced expression of wild-type IκBα had no significant impact on the ctgf promoter activity (Figure 2b). However, the specific inhibition of NF-κB activation by forced expression of dn-IκBα caused a dose-dependent reduction in the ctgf promoter activity (Figure 2b), suggesting that the inhibition of NF-κB activity might suppress gene expression of CTGF in passaged HSC. Taken together, our results in Figure 2 demonstrated that the alteration in the activity of NF-κB significantly influenced the ctgf promoter activity, suggesting that NF-κB might play a critical role in the regulation of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC in vitro.

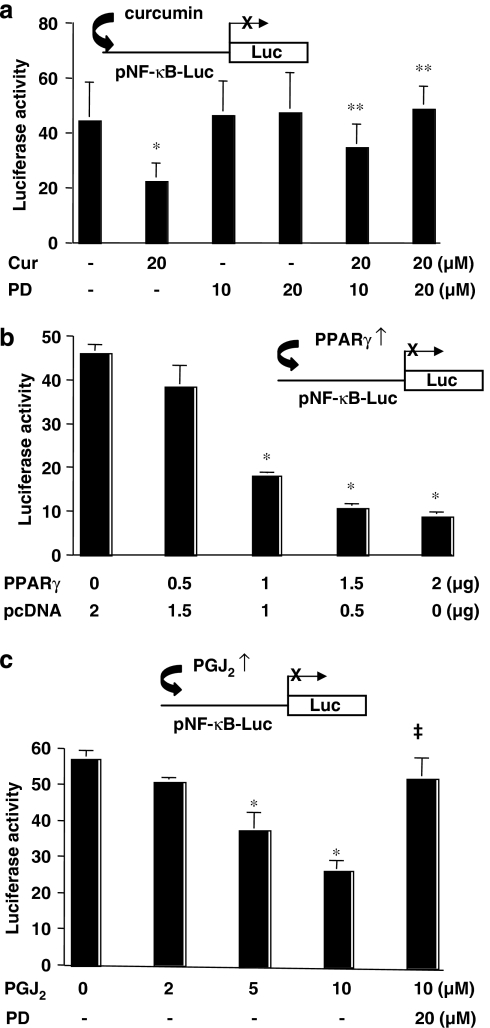

Activation of PPARγ signalling reduces the activity of NF-κB in activated HSC in vitro

Activation of PPARγ was required for curcumin to inhibit gene expression of CTGF (Zheng and Chen, 2006) and it was therefore likely that curcumin activation of PPARγ signalling might also be required for its inhibition of NF-κB, leading to the inhibition of ctgf expression. To test this assumption, passaged HSCs were transiently transfected with the NF-κB transactivity reporter plasmid pNF-κB-Luc. After recovery, cells were pretreated with or without PD68235, a specific PPARγ antagonist (Camp et al., 2001), for 30 min prior to the addition of curcumin (20 μM) for additional 24 h. As shown in Figure 3a by luciferase assays, compared to the untreated control (the first column on the left), curcumin, as expected, significantly reduced luciferase activity (the second column on the left). In contrast, pretreatment of cells with the specific PPARγ antagonist dose-dependently eliminated the inhibitory effect of curcumin (the last two columns on the right). PD68235 itself at 10 or 20 μM showed no significant effect on luciferase activity. These results suggested that the activation of PPARγ might be required for the curcumin inhibition of the NF-κB transactivation activity in passaged HSC. To verify the role of activation of PPARγ in the inhibition of NF-κB activity, passaged HSCs were co-transfected with the plasmid pNF-κB-Luc and the PPARγ cDNA-expressing plasmid pPPARγcDNA at indicated doses. A total of 4.5 μg of plasmid DNA per well was used for the co-transfection of HSC in six-well culture plates. It included 2 μg of pNF-κB-Luc, 0.5 μg of pSV-β-gal and 2 μg of pPPARγcDNA at indicated doses plus the empty vector pcDNA. The latter was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After recovery, cells were cultured for 24 h. As shown in Figure 3b, forced expression of exogenous PPARγ cDNA dose-dependently reduced luciferase activity, indicating the reduction in the transactivation activity of NF-κB. The inhibitory effect of exogenous PPARγ cDNA was abrogated by treatment of cells with the PPARγ antagonist PD68235 (data not shown). Prior experiments have suggested that 10% of FBS in the medium might contain enough agonists to activate PPARγ in HSC (Miyahara et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2003; Zheng and Chen, 2004, 2006). To further confirm the inhibitory role of PPARγ signalling, HSCs transfected with pNF-κB-Luc were treated with 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), a natural PPARγ ligand, at indicated concentrations for 24 h. It was observed that the activation of PPARγ signalling by 15d-PGJ2 dose-dependently reduced the transactivation activity of NF-κB in HSC, which could be eliminated by pretreatment with PD68235 (the last column on the right) (Figure 3c). PD68235 itself at 20 μM showed no significant effect on luciferase activity (data not shown here). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the activation of PPARγ signalling reduced the transactivation activity of NF-κB in activated HSC in vitro. Assay of the cytotoxicity of the drug mixture used here showed that the mixture of the chemicals made no significant difference in the level of LDH in the medium and in the number of Trypan blue-stained HSCs compared with the untreated control. Cell growth rapidly recovered after withdrawal of the chemicals (data not shown). It was, therefore, concluded that the chemicals in this study were not toxic to cultured HSCs.

Figure 3.

Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) reduces nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activity in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. Semiconfluent HSCs were transiently transfected with the plasmid pNF-κB-Luc. After overnight recovery, cells were pretreated with or without the specific PPARγ inhibitor PD68235 (10 or 20 μM) for 30 min prior to the treatment as indicated in the following for additional 24 h. Luciferase assays were performed. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative units after β-galactosidase normalization (means±s.d.; n⩾6). *P<0.05 versus cells with no treatment (the first column on the left). **P<0.05 versus cells with curcumin only (the second column on the left). The insets denote the pNF-κB-Luc construct in use and the application of a treatment, or a co-transfected plasmid, to the system. (a) Cells were treated with curcumin (Cur; 20 μM) with or without PD68235 (PD; 10 or 20 μM). (b) Cells were co-transfected with the PPARγ cDNA expression plasmid pPPARγ at indicated doses. A total of 4.5 μg of plasmid DNA per well was transfected to HSC in six-well culture plates. It included 2 μg of pNF-κB-Luc, 0.5 μg of pSV-β-gal and 2 μg of pPPARγ at indicated doses plus the empty vector pcDNA. The latter was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After overnight recovery, cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%) for 24 h with no additional treatment. (c) Cells were treated with the natural PPARγ agonist 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2) at the indicated concentrations with or without PD68235 (20 μM).

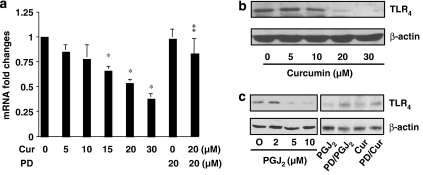

Activation of PPARγ suppresses gene expression of TLR4 in activated HSC in vitro

TLR4, which acts as an LPS receptor, is involved in the activation of HSC (Paik et al., 2003). We therefore evaluated the effects of curcumin on gene expression of TLR4 in activated HSC. Semiconfluent passaged HSCs were treated with curcumin at indicated concentrations for 24 h with or without pretreatment with the PPARγ antagonist PD68235 for 30 min. Total RNA and whole-cell extracts were prepared from these cells. As shown in Figure 4 by real-time PCR and western blotting analyses, respectively, curcumin significantly and dose-dependently reduced gene expression of TLR4 in activated HSC in vitro (Figures 4a and b). The inhibitory effect was eliminated by the pretreatment with PD68235, suggesting that the activation of PPARγ signalling might play a critical role in the curcumin inhibition of TLR4 gene expression. Further experiments revealed that the activation of PPARγ by 15d-PGJ2 caused a dose-dependent reduction in the abundance of TLR4 in HSC (Figure 4c). Pretreatment with the PPARγ antagonist dramatically reduced the inhibitory effect caused by 15d-PGJ2, as well as by curcumin (Figure 4c). These results collectively suggested that the activation of PPARγ by curcumin might result in the suppression of gene expression of TLR4, which could lead to the inhibition of NF-κB activity in activated HSC in vitro.

Figure 4.

Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) suppresses gene expression of TLR4 in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. Semiconfluent HSCs were pretreated with or without the specific PPARγ inhibitor PD68235 (20 μM) for 30 min prior to the treatment as indicated, for an additional 24 h. Total RNA or whole-cell extracts were prepared from these cells. (a) Real-time PCR analyses of the steady-state levels of TLR4 in cells treated with curcumin at indicated concentrations. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an invariant control for calculating mRNA fold changes. Values are expressed as means±s.d. (n=3). *P<0.05 versus the untreated control (the first column on the left). (b) Western blotting analyses of the abundance of TLR4 in cells treated with curcumin at indicated concentrations. β-Actin was used as an invariant control for equal loading. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown. (c) Western blotting analyses of the abundance of TLR4 in cells treated with 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) (PGJ2) at indicated concentrations, or with 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) or curcumin (Cur; 20 μM), with or without the pre-exposure to PD68235 (PD; 20 μM). β-Actin was used as an invariant control for equal loading. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown.

Interruption by curcumin of the ERK signalling pathway suppresses CTGF gene expression in HSC

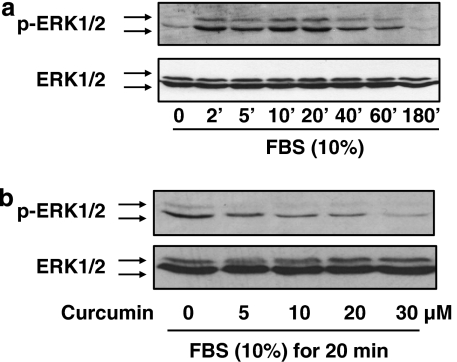

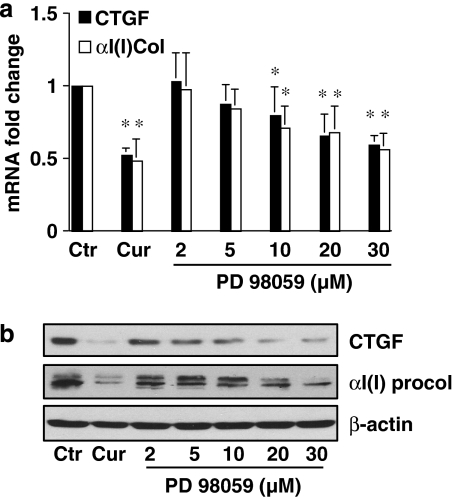

The ERK signalling pathway plays a key role in the activation of HSC (Pinzani, 2002; Perez de Obanos et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2007). We evaluated the effect of curcumin on the ERK signalling pathway and its role in the inhibition of gene expression of CTGF in HSC. Pilot experiments revealed that FBS (10%) rapidly stimulated ERK activity in serum-starved HSC, as demonstrated by the increase in the level of phosphorylated ERK (Figure 5a). The peak of ERK activation is probably within 20 min after FBS stimulation. To evaluate the effect of curcumin on ERK activity, serum-starved HSCs were pretreated with curcumin at indicated concentrations for 30 min prior to stimulation with FBS (10%) for an additional 20 min. Whole-cell extracts were prepared for western blotting analyses. As shown in Figure 5b, the level of phosphorylated ERK was significantly and dose-dependently reduced by curcumin, suggesting that curcumin might inhibit ERK activity in these cells. To determine the role of the curcumin inhibition of ERK activity in the regulation of gene expression of CTGF, semiconfluent HSCs were treated with curcumin at 20 μM or with the specific ERK inhibitor PD98059 at various concentrations for 24 h. Total RNA and whole-cell extracts were prepared from these cells. As shown in Figures 6a and b by real-time PCR and western blotting analyses, respectively, PD 98059, like curcumin (the second column, or well), significantly and dose-dependently reduced the steady-state level of mRNA and the protein abundance of CTGF and αI(I) procollagen, indicating that the inhibition of ERK activity resulted in the suppression of gene expression of CTGF and αI(I) collagen in HSC. These results collectively suggested that the curcumin interruption of the ERK signalling pathway might result in the suppression of gene expression of CTGF in HSC.

Figure 5.

Curcumin inhibits the activation of ERK in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. After serum starvation for 48 h, HSCs were stimulated with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%). Whole-cell extracts were prepared for western blotting analyses of the level of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2). Total ERK1/2 was used as an internal invariant control for equal loading. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown. (a) Serum-starved cells were stimulated with FBS (10%) for indicated minutes. (b) Serum-starved cells were pretreated with curcumin at indicated concentration for 30 min prior to the stimulation with FBS (10%) for additional 20 min.

Figure 6.

The inhibition of ERK activity by PD98059 suppresses gene expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and αI(I) collagen in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. Serum-starved cells were pretreated with curcumin (Cur) at 20 μM or with PD98059 at indicated concentrations for 30 min prior to the stimulation with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%) for additional 24 h. Total RNA or whole-cell extracts were prepared from these cells. (a) Real-time PCR analyses of the steady-state levels of CTGF and αI(I) procollagen (αI(I) col). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an invariant control for calculating mRNA fold changes. Values are expressed as means±s.d. (n=3). *P<0.05, versus the untreated control (the corresponding first column on the left). (b) Western blotting analyses of the abundance of CTGF and αI(I) procollagen (αI(I) procol). β-Actin was used as an invariant control for equal loading. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown.

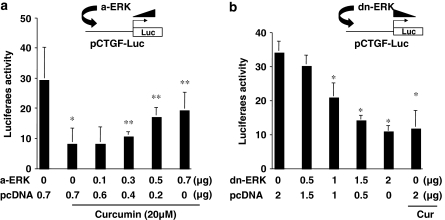

To confirm the role of ERK in the regulation of CTGF gene expression, HSCs were co-transfected with pCTGF-Luc plus a cDNA-expressing plasmid of pa-ERK or pdn-ERK. The cDNA expression plasmid pa-ERK, or pdn-ERK, contains a full length of cDNA encoding the constitutively a-ERK or the dominant-negative form of ERK (dn-ERK), respectively (Davis et al., 1996). A total of 3.2 or 4.5 μg of plasmid DNA per well was used for the co-transfection of HSC in six-well culture plates. It included 2 μg of pCTGF-Luc, 0.5 μg of pSV-β-gal and 0.7 μg (Figure 7a) or 2 μg (Figure 7b) of a cDNA expression plasmid at indicated doses plus the empty vector pcDNA. The latter was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After recovery, cells were serum-starved in DMEM for 24 h prior to the stimulation with FBS (10%) in the presence and absence of curcumin (20 μM) for additional 24 h. As shown in Figure 7a by luciferase assays, compared with the untreated control (the first column on the left), curcumin (the second column on the left), as expected, dramatically reduced luciferase activity. The activation of ERK by forced expression of a-ERK dose-dependently increased luciferase activity and eliminated the inhibitory effect of curcumin on CTGF gene promoter (Figure 7a). On the other hand, the interruption of ERK signalling by expression of dn-ERK in Figure 7b, like curcumin (the last column on the right), dose-dependently reduced luciferase activity, suggesting the suppression of the ctgf promoter activity. Taken together, our results demonstrated that the inhibition of ERK activity by curcumin resulted in the suppression of CTGF gene expression in HSC.

Figure 7.

ERK activity plays a role in the regulation of the promoter activity of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. HSCs were co-transfected with pCTGF-Luc (2 μg per well) plus a cDNA-expressing plasmid of pa-ERK (a-ERK) or pdn-ERK (dn-ERK) at indicated doses. The empty vector pcDNA was used to ensure an equal amount of total DNA in transfection assays. After overnight recovery, cells were serum-starved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) for 24 h prior to the stimulation with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%) in the presence and absence of curcumin (20 μM) for additional 24 h. Luciferase assays were performed. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative units after β-galactosidase normalization (means±s.d.; n⩾6). *P<0.05 versus cells with no treatment (the first column on the left); **P<0.05 versus cells transfected with pcDNA only (the second column on the left). (a) Luciferase assays of cells co-transfected with pCTGF-Luc plus pa-ERK. (b) Luciferase assays of cells co-transfected with pCTGF-Luc plus pdn-ERK.

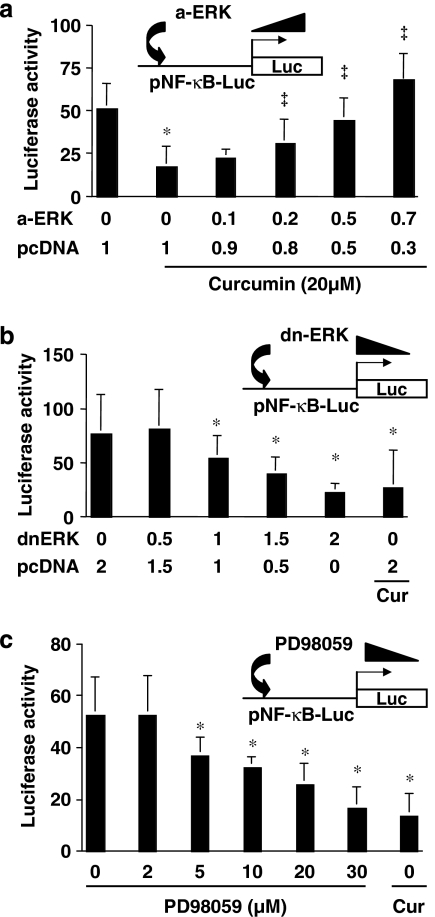

Inhibition of ERK activity by curcumin facilitates the reduction in NF-κB activity in HSC

Studies have suggested a cross-talk between the signalling pathways of ERK and NF-κB (Aga et al., 2004; Kefaloyianni et al., 2006). We postulated that the inhibition of ERK activity by curcumin might facilitate the reduction in NF-κB activity, leading to the inhibition of CTGF gene expression in HSC. To assess this postulate, HSCs were co-transfected with the NF-κB activity reporter plasmid pNF-κB-Luc plus a cDNA-expressing plasmid of pa-ERK or pdn-ERK at indicated doses. After recovery, cells were serum-starved in DMEM for 24 h prior to the stimulation with FBS (10%) in the presence and absence of curcumin (20 μM) for additional 24 h. As shown in Figure 8a by luciferase assays, compared with the untreated control (the first column on the left), curcumin (the second column on the left), as expected, dramatically reduced luciferase activity. The activation of ERK by a-ERK dose-dependently eliminated the inhibitory effect of curcumin on NF-κB activity (Figure 8a). On the other hand, the interruption of ERK signalling by dn-ERK, like curcumin (the last column on the right), dose-dependently reduced luciferase activity, suggesting the suppression of NF-κB activity (Figure 8b). To further confirm the effect of ERK activity on NF-κB activity, HSCs transfected with pNF-κB-Luc were treated with the specific ERK inhibitor PD98059 at indicated concentrations for 24 h. Luciferase assays demonstrate that PD98059, like curcumin (the last column on the right), dose-dependently suppressed NF-κB activity (Figure 8c). These results collectively suggested that the inhibition of ERK activity by curcumin might result in the reduction in NF-κB activity, leading to the suppression of CTGF gene expression in HSC.

Figure 8.

ERK activity affects the transactivation activity of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in activated hepatic stellate cell (HSC) in vitro. HSCs were co-transfected with the plasmid pNF-κB-Luc plus pa-ERK or pdn-ERK at indicated doses. After recovery, cells were serum-starved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) for 24 h prior to the stimulation with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%) in the presence and absence of curcumin (20 μM) for additional 24 h. Luciferase assays were performed. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative units after β-galactosidase normalization (means±s.d.; n⩾6). *P<0.05 versus cells with no treatment (the first column on the left); ‡P<0.05 versus cells transfected with pcDNA only (the second column on the left). (a) Luciferase assays of cells co-transfected with pNF-κB-Luc plus pa-ERK. (b) Luciferase assays of cells co-transfected with pNF-κB-Luc plus pdn-ERK. (c) Luciferase assays of cells transfected with pNF-κB-Luc only, and then treated with the ERK inhibitor PD98059 at indicated concentrations for 24 h.

Discussion

Suppression of HSC activation and prevention of hepatic fibrogenesis attract the attention of researchers from the therapeutic perspective. Many of them have focused their attention on searching for novel agents with inhibitory effects on HSC activation (Friedman, 2004). We recently showed that curcumin inhibited gene expression of CTGF, leading to the reduction in the production of ECM components in activated HSC (Zheng and Chen, 2006). The purpose of this study was to investigate signal transduction pathways involved in the curcumin suppression of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC. To analyse the promoter activity of CTGF, the plasmid pCTGF-Luc, containing a fragment of the CTGF gene promoter (∼2000 bp nucleotides), was used in most of this study. In this study, we demonstrated the critical role of NF-κB activity in the regulation of CTGF gene expression in HSC. Curcumin suppressed gene expression of TLR4, leading to the inhibition of NF-κB activity. In addition, our results revealed the effect of ERK activation on NF-κB activity and on the regulation of CTGF gene expression in HSC. Taken together, the present results supported our hypothesis and demonstrated that the inhibition of NF-κB and ERK signalling pathways by curcumin resulted in the suppression of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC.

We are aware that the absorption of dietary curcumin is relatively low and curcumin disappears from rodent tissues relatively rapidly (Perkins et al., 2002). Curcumin is unstable in vivo and its derivatives might function as the active forms of curcumin in vivo (Pan et al., 1999). Its effective concentration and its effective metabolites in vivo remain largely unknown (Pan et al., 1999). The cytotoxicity of curcumin to cultured HSC was evaluated previously (Xu et al., 2003). Based on results from LDH release assays, Trypan blue exclusion assays and a rapid recovery of cell proliferation after withdrawal of curcumin, it was concluded that curcumin up to 100 μM was not toxic to cultured HSC. Curcumin at 20 μM or lower has been chosen for most of our studies in this study, which is much higher than those observed in blood and/or tissues of human and animals (Ammon and Wahl, 1991; Pan et al., 1999). However, it must be noted that because the in vivo system is multifactorial, directly extrapolating in vitro conditions and results, for example, effective concentrations, to the in vivo system might be misleading. We recently observed that oral administration of curcumin at 200 mg/kg body weight significantly reduced the level of the transcript and protein of CTGF in the liver, inhibited HSC activation and protected the liver from injury caused by CCl4 (unpublished data).

We and others have demonstrated previously that curcumin inhibits NF-κB activity in HSC and other cell types (Xu et al., 2003; Kamat et al., 2007; Shakibaei et al., 2007). In the present study, we demonstrated that the inhibition of NF-κB by curcumin played a critical role in the suppression of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC in vitro. Our results are consistent with prior observations (Bourgier et al., 2005; Hong et al., 2006). Two potential NF-κB-binding sites were located within −545 to −535 and −94 to −83 in the promoter of the gene encoding CTGF (Fu et al., 2001). Our promoter deletion assays confirmed the necessity of these two regions containing the two NF-κB-binding sites in responding to curcumin (data not shown here). Additional experiments are being conducted in our lab to clarify proteins binding to the sites using site-directed mutagenesis, gel shift assays and chromosomal immunoprecipitation. Other reports also showed that hypoxia increased NF-κB activity, leading to the induction of expression of CTGF in scleroderma skin fibroblasts (Hong et al., 2006). Inhibition of Rho kinase reduced the level of CTGF mediated by the inhibition of NF-κB, leading to the reduced expression of type I collagen gene in intestinal smooth muscle cells (Bourgier et al., 2005). However, our study has limitations and additional experiments are required.

It remains largely unknown how curcumin suppresses the activity of NF-κB, leading to the suppression of CTGF gene expression. The IκB-α/NF-κB pathway is redox-sensitive and LPS induces NF-κB activation through changes in the redox equilibrium (Haddad and Land, 2002). Inhibition of glutathione biosynthesis by L-buthionine-(S,R)-sulphoximine blocks the LPS-induced phosphorylation of IκB-α, reduces its degradation and inhibits NF-κB activation (Haddad and Land, 2002). We recently demonstrated that curcumin was a potent antioxidant (Zheng et al., 2007). It induced gene expression of glutamate-cysteine ligase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of glutathione, in cultured HSC (Zheng et al., 2007). Additional experiments are ongoing in our laboratory to evaluate the role of the antioxidant capability of curcumin in the inhibition of NF-κB and in the suppression of CTGF gene expression in HSC.

Activation of HSC is coupled with a dramatic reduction in the level of PPARγ and its activity in vitro and in vivo (Galli et al., 2000; Marra et al., 2000; Miyahara et al., 2000). Stimulating PPARγ activity by its agonists inhibits HSC proliferation and α1(I) collagen expression in vitro and in vivo (Miyahara et al., 2000; Galli et al., 2002). Forced expression of exogenous PPARγ cDNA is sufficient to reverse the morphology of activated HSC to the quiescent phenotype (Hazra et al., 2004). We demonstrated previously that curcumin induced gene expression of endogenous PPARγ and stimulated its activity in activated HSC in vitro (Xu et al., 2003), which was a prerequisite for curcumin to inhibit cell growth and to suppress gene expression of ECM (Xu et al., 2003; Zheng and Chen, 2004, 2006). The impact of the curcumin activation of PPARγ on NF-κB activity was studied here. Our results suggested that the activation of PPARγ resulted in the inhibition of NF-κB activity in activated HSC, which might be mediated by the suppression of gene expression of TLR4. TLR4, responsible for the recognition of LPS, has been known to mediate LPS-induced cellular signalling through activation of NF-κB pathway (Eun et al., 2006). TLR4 is hardly detectable in quiescent HSC but its expression is highly induced in activated HSC (Paik et al., 2003). TLR4 mediates inflammatory signalling by LPS, leading to the activation of NF-κB during hepatic fibrogenesis (Paik et al., 2003). Our results are compatible with prior reports. Activation of PPARγ or TLR4 could initiate two antagonistic signalling pathways in intestinal epithelial cells. They may be partially crosslinked (Eun et al., 2006), as PPARγ ligand delays LPS-induced IκBα degradation and reduces TLR4 expression. On the other hand, TLR4 negatively regulates PPARγ expression and its anti-inflammatory properties in the development of inflammatory bowel disease (Rousseaux and Desreumaux, 2006). Additional experiments are necessary to elucidate the mechanisms of PPARγ in the regulation of TLR4 gene expression (Dubuquoy et al., 2003).

We further evaluated the role of the ERK signalling pathway in the curcumin inhibition of CTGF gene expression. Results in this study demonstrated that the curcumin inhibition of ERK activity resulted in the reduction in NF-κB activity and in the expression of CTGF gene in activated HSC in vitro. Our results are consistent with prior studies (Mulsow et al., 2005; Shimo et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2007). Taurine, a non-essential amino acid, promoted CTGF gene expression in osteoblasts through the activation of the ERK signalling pathway (Yuan et al., 2007). Pretreatment of osteoblasts with the ERK inhibitor PD98059 abolished the taurine-induced CTGF production. CTGF is transcriptionally regulated by TGF-β (Fu et al., 2001; Blom et al., 2002; Leask et al., 2003) and this regulation might be Ras/MEK/ERK dependent (Phanish et al., 2005). We reported previously that curcumin suppressed CTGF gene expression in activated HSC by interruption of TGF-β signalling (Zheng and Chen, 2006) and there is evidence for cross-talk between the ERK signalling pathway and TGF-β signalling (Mulder, 2000; Wang et al., 2005; Huo et al., 2007), as well as NF-κB signalling (Kefaloyianni et al., 2006). Experiments are ongoing in our laboratory to elucidate mechanisms of ERK and NF-κB signalling pathways in the curcumin interruption of TGF-β signalling, and to further explore mechanisms of cross-talk between them in the regulation of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC.

Based on our observations, a simplified pathway is proposed to describe the possible involvement of signalling pathways in the curcumin inhibition of CTGF gene expression in activated HSC in vitro. Curcumin reduces NF-κB activity by suppressing gene expression of TLR4, which is mediated by activation of PPARγ signalling. In addition, curcumin inhibits ERK activity, which also facilitates the reduction in NF-κB activity. Furthermore, the curcumin inhibition of ERK activity might interfere with other signalling pathways, including TGF-β signalling. These inhibitory effects might collectively reduce the promoter activity of CTGF and suppress its gene expression in activated HSC in vitro. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms are certainly more complex than it is described here. In addition, our results do not exclude possible involvement of any other signalling pathways and mechanisms in the curcumin inhibition of CTGF gene expression. These results provide novel insights into the mechanisms of curcumin in the inhibition of gene expression of CTGF and ECM components, leading to the inhibition of HSC activation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant RO1 DK 047995 from NIH/NIDDK to A Chen.

Abbreviations

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-beta

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Aga M, Watters JJ, Pfeiffer ZA, Wiepz GJ, Sommer JA, Bertics PJ. Evidence for nucleotide receptor modulation of cross talk between MAP kinase and NF-kappa B signaling pathways in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C923–C930. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00417.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon HP, Wahl MA. Pharmacology of Curcuma longa. Planta Med. 1991;57:1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom IE, Goldschmeding R, Leask A. Gene regulation of connective tissue growth factor: new targets for antifibrotic therapy. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:473–482. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgier C, Haydont V, Milliat F, Francois A, Holler V, Lasser P, et al. Inhibition of Rho kinase modulates radiation induced fibrogenic phenotype in intestinal smooth muscle cells through alteration of the cytoskeleton and connective tissue growth factor expression. Gut. 2005;54:336–343. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Gerstberger S, Carlson L, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Control of I kappa B-alpha proteolysis by site-specific, signal-induced phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.7878466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp HS, Chaudhry A, Leff T. A novel potent antagonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma blocks adipocyte differentiation but does not revert the phenotype of terminally differentiated adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3207–3213. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Davis BH. The DNA binding protein BTEB mediates acetaldehyde-induced, jun N-terminal kinase-dependent alphaI(I) collagen gene expression in rat hepatic stellate cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2818–2826. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2818-2826.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Zhang L, Xu J, Tang J. The antioxidant (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits activated hepatic stellate cell growth and suppresses acetaldehyde-induced gene expression. Biochem J. 2002;368:695–704. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BH, Chen A, Beno DW. Raf and mitogen-activated protein kinase regulate stellate cell collagen gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11039–11042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuquoy L, Jansson EA, Deeb S, Rakotobe S, Karoui M, Colombel JF, et al. Impaired expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1265–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun CS, Han DS, Lee SH, Paik CH, Chung YW, Lee J, et al. Attenuation of colonic inflammation by PPARgamma in intestinal epithelial cells: effect on Toll-like receptor pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:693–697. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL. Stellate cells: a moving target in hepatic fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 2004;40:1041–1043. doi: 10.1002/hep.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M, Zhang J, Zhu X, Myles DE, Willson TM, Liu X, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits transforming growth factor beta-induced connective tissue growth factor expression in human aortic smooth muscle cells by interfering with Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45888–45894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Zhou Y, Zheng S, Chen A. The antifibrogenic effect of (–)-epigallocatechin gallate results from the induction of de novo synthesis of glutathione in passaged rat hepatic stellate cells. Lab Invest. 2006;86:697–709. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli A, Crabb D, Price D, Ceni E, Salzano R, Surrenti C, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transcriptional regulation is involved in platelet-derived growth factor-induced proliferation of human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2000;31:101–108. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli A, Crabb DW, Ceni E, Salzano R, Mello T, Svegliati-Baroni G, et al. Antidiabetic thiazolidinediones inhibit collagen synthesis and hepatic stellate cell activation in vivo and in vitro. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1924–1940. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker H, Karin M. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re13. doi: 10.1126/stke.3572006re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad JJ, Land SC. Redox signaling-mediated regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis in alveolar epithelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:179–193. doi: 10.1089/152308602753625942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra S, Xiong S, Wang J, Rippe RA, Krishna V, Chatterjee K, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma induces a phenotypic switch from activated to quiescent hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11392–11401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerbrand C, Jobin C, Licato LL, Sartor RB, Brenner DA. Cytokines induce NF-kappaB in activated but not in quiescent rat hepatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G269–G278. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.2.G269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong KH, Yoo SA, Kang SS, Choi JJ, Kim WU, Cho CS. Hypoxia induces expression of connective tissue growth factor in scleroderma skin fibroblasts. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:362–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo YY, Hu YC, He XR, Wang Y, Song BQ, Zhou PK, et al. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by TGF-beta1 via TbetaRII and Smad7 dependent mechanisms in human bronchial epithelial BEP2D cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2007;23:113–128. doi: 10.1007/s10565-006-0097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat AM, Sethi G, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin potentiates the apoptotic effects of chemotherapeutic agents and cytokines through down-regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB and nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene products in IFN-alpha-sensitive and IFN-alpha-resistant human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1022–1030. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kefaloyianni E, Gaitanaki C, Beis I. ERK1/2 and p38-MAPK signalling pathways, through MSK1, are involved in NF-kappaB transactivation during oxidative stress in skeletal myoblasts. Cell Signal. 2006;18:2238–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Hepatic stellate cells and the reversal of fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21 Suppl 3:S84–S87. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Inoue T, Okada H, Kikuta T, Kanno Y, Nishida T, et al. Connective tissue growth factor mediates the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-beta produced by tubular epithelial cells in response to high glucose. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2005;9:114–121. doi: 10.1007/s10157-005-0347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Holmes A, Black CM, Abraham DJ. Connective tissue growth factor gene regulation. Requirements for its induction by transforming growth factor-beta 2 in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13008–13015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra F, Efsen E, Romanelli RG, Caligiuri A, Pastacaldi S, Batignani G, et al. Ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma modulate profibrogenic and proinflammatory actions in hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:466–478. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahara T, Schrum L, Rippe R, Xiong S, Yee HF, Jr, Motomura K, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and hepatic stellate cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35715–35722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder KM. Role of Ras and Mapks in TGFbeta signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsow JJ, Watson RW, Fitzpatrick JM, O'Connell PR.Transforming growth factor-beta promotes pro-fibrotic behavior by serosal fibroblasts via PKC and ERK1/2 mitogen activated protein kinase cell signaling Ann Surg 2005242880–887.discussion 887–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–1055. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan MH, Huang TM, Lin JK. Biotransformation of curcumin through reduction and glucuronidation in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis V, Dargere D, Bonvoust F, Vidaud M, Segarini P, Bedossa P. Effects and regulation of connective tissue growth factor on hepatic stellate cells. Lab Invest. 2002;82:767–774. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000017365.18894.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis V, Dargere D, Vidaud M, De Gouville AC, Huet S, Martinez V, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in experimental rat and human liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:968–976. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Jeon CH, Ko G, Kim J, Sohn DH. Protective effect of curcumin in rat liver injury induced by carbon tetrachloride. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52:437–440. doi: 10.1211/0022357001774048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez de Obanos MP, Lopez Zabalza MJ, Prieto J, Herraiz MT, Iraburu MJ. Leucine stimulates procollagen alpha1(I) translation on hepatic stellate cells through ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:580–586. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins S, Verschoyle RD, Hill K, Parveen I, Threadgill MD, Sharma RA, et al. Chemopreventive efficacy and pharmacokinetics of curcumin in the min/+ mouse, a model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:535–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanish MK, Wahab NA, Hendry BM, Dockrell ME. TGF-beta1-induced connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) expression in human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells requires Ras/MEK/ERK and Smad signalling. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;100:e156–e165. doi: 10.1159/000085445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzani M. PDGF and signal transduction in hepatic stellate cells. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1720–d1726. doi: 10.2741/A875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippe RA, Schrum LW, Stefanovic B, Solis-Herruzo JA, Brenner DA. NF-kappaB inhibits expression of the alpha1(I) collagen gene. DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18:751–761. doi: 10.1089/104454999314890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseaux C, Desreumaux P. The peroxisome-proliferator-activated gamma receptor and chronic inflammatory bowel disease (PPARgamma and IBD) J Soc Biol. 2006;200:121–131. doi: 10.1051/jbio:2006015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Zakrajsek BA, Mills AG, Gorn V, Singer MJ, Reed MW. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal Biochem. 2000;285:194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakibaei M, John T, Schulze-Tanzil G, Lehmann I, Mobasheri A. Suppression of NF-kappaB activation by curcumin leads to inhibition of expression of cyclo-oxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in human articular chondrocytes: implications for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1434–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimo T, Kubota S, Yoshioka N, Ibaragi S, Isowa S, Eguchi T, et al. Pathogenic role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in osteolytic metastasis of breast cancer. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1045–1059. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchio K, Graham M, Dean NM, Rosenbaum J, Desmouliere A. Down-regulation of connective tissue growth factor and type I collagen mRNA expression by connective tissue growth factor antisense oligonucleotide during experimental liver fibrosis. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12:60–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.012112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Koka V, Lan HY. Transforming growth factor-beta and Smad signalling in kidney diseases. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EJ, Gaca MD, Brigstock DR, Arthur MJ, Benyon RC. Increased expression of connective tissue growth factor in fibrotic human liver and in activated hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2000;32:754–761. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R, Liu FY, Luo JY, Yang XJ, Wen HQ, Su YW, et al. Effect of small interfering RNA on the expression of connective tissue growth factor and type I and III collagen in skin fibroblasts of patients with systemic sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Fu Y, Chen A. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma contributes to the inhibitory effects of curcumin on rat hepatic stellate cell growth. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G20–G30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00474.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Yeh J, Van Waes C. Protein kinase casein kinase 2 mediates inhibitor-kappaB kinase and aberrant nuclear factor-kappaB activation by serum factor(s) in head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6722–6731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan LQ, Lu Y, Luo XH, Xie H, Wu XP, Liao EY. Taurine promotes connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression in osteoblasts through the ERK signal pathway. Amino Acids. 2007;32:425–430. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Chen A. Activation of PPARgamma is required for curcumin to induce apoptosis and to inhibit the expression of extracellular matrix genes in hepatic stellate cells in vitro. Biochem J. 2004;384:149–157. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Chen A. Curcumin suppresses the expression of extracellular matrix genes in activated hepatic stellate cells by inhibiting gene expression of connective tissue growth factor. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G883–G893. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00450.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Fu Y, Chen A. De novo synthesis of glutathione is a prerequisite for curcumin to inhibit hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zheng S, Lin J, Zhang QJ, Chen A. The interruption of the PDGF and EGF signaling pathways by curcumin stimulates gene expression of PPARgamma in rat activated hepatic stellate cell in vitro. Lab Invest. 2007;87:488–498. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]