Abstract

The identification of surface-exposed components of the major outer membrane protein (MOMP) of Chlamydia is critical for modeling its three-dimensional structure, as well as for understanding the role of MOMP in the pathogenesis of Chlamydia-related diseases. MOMP contains four variable domains (VDs). In this study, VDII and VDIV of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar F were proven to be surface-located by immuno-dot blot assay using monoclonal antibodies (MAbs). Two proteases, trypsin and endoproteinase Glu-C, were applied to digest the intact elementary body of serovar F under native conditions to reveal the surface-located amino acids. The resulting peptides were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with MAbs against these VDs. N-terminal amino acid sequencing revealed: (1) The Glu-C cleavage sites were located within VDI (at Glu61) and VDIII (at Glu225); (2) the trypsin cleavage sites were found at Lys79 in VDI and at Lys224 in VDIII. The tryptic peptides were then isolated by HPLC and analyzed with a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer and a quadrupole-orthogonal-TOF mass spectrometer coupled with a capillary liquid chromatograph. Masses and fragmentation patterns that correlated to the peptides cleaved from VDI and VDIII regions, and C-terminal peptides Ser333–Arg358 and Ser333–Lys350 were observed. This result demonstrated that these regions are surface-exposed. Data derived from comparison of nonreduced outer membrane complex proteolytic fragments with their reduced fractions revealed that Cys26, 29, 33, 116, 208, and 337 were involved in disulfide bonds, and Cys26 and 337, and 116 and 208 were paired. Based on these data, a new two-dimensional model is proposed.

Keywords: MOMP, surface-exposed components, mass spectrometry, topology of MOMP

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens that cause a broad spectrum of clinically distinct diseases in humans and animals. In particular, pathogenic species for humans are Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Chlamydia psittaci (Grayston et al. 1989; Fukushi and Hirai 1992). Of these, C. trachomatis has been recognized as the worldwide leading cause of sexually transmitted bacterial diseases (Schachter 1999). It also causes trachoma, which represents the leading cause of preventable blindness in developing countries (Schachter 1999). A unique developmental cycle distinguishes Chlamydia from other intracellular bacteria (Moulder et al. 1984). Two major developmental forms, the infectious elementary body (EB) and the vegetative reticulate body (RB), are involved in the cycle. The EB is small, dense, rigid, metabolically inert, and resistant to the hostile extracellular environment. After attaching to and promoting entry into the target host cell, the EB remains within a phagosome and differentiates into the large, low-density, less rigid, metabolically active but noninfectious RB. Following several rounds of replication (binary fission), the resulting RB forms redifferentiate into EB forms.

One of the predominant proteins at the surface of both EB and RB forms is the major outer membrane protein (MOMP, OmpA). MOMP makes up 60% of total outer membrane protein (Caldwell et al. 1981) and has a molecular mass of ~40 kDa. As a set of surface-exposed molecules, MOMP is susceptible to surface radioiodination (Caldwell et al. 1981; Salari and Ward 1981), recognized by monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (Kuo and Chi 1987, Zhang et al. 1987), and is cleavable by trypsin (Su et al. 1988). Published data have indicated that chlamydial MOMP functions as a structural protein (Hatch 1996), a general porin (Bavoil et al. 1984; Wyllie et al. 1998; Jones et al. 2000), and a potential chlamydial cytoadhesin (Su et al. 1990; Swanson and Kuo 1994). Therefore, it is critical for chlamydial infection.

The most widely studied and accepted function of MOMP is that of a porin. Porins are a family of membrane channels commonly found in the outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria, where they serve as diffusion pathways for nutrients, waste products, and antibiotics and can also be receptors for bacteriophages (for review, see Miot and Betton 2004). Bavoil et al. (1984) demonstrated that outer membrane complexes (OMCs) of C. trachomatis contained water-filled pores with an exclusion limit of 850–2250 Da by liposome swelling assay. Wyllie et al. (1998) confirmed these data by measuring the conductance of planar lipid bilayers containing proteins from chlamydial OMCs. By use of circular dichroism analysis, Wyllie et al. (1998) showed that MOMP purified from C. psittaci has a predominant β-sheet content (62%). This is also a typical characteristic of bacterial porins. MOMP channels were weakly anion selective (PCl/PK ~2) and permeable to ATP. Jones et al. (2000) transferred Escherichia coli outer membranes containing full-length C. trachomatis MOMP to liposomes and observed MOMP facilitated the diffusion of solutes in liposomes. They demonstrated that the function of MOMP was to serve as a general diffusion porin. They additionally showed that MOMP was strongly size-selective, but not ion-selective, for promoting the diffusion of solutes.

Elucidation of the structure of MOMP is crucial for our understanding of the role of MOMP in chlamydial infection and also will facilitate the design of MOMP-based diagnostics or vaccines. However, despite many years of hard work, the real structure of the MOMP molecule is still unknown. Using two secondary structure prediction methods (Schirmer and Cowan 1993; Diederichs et al. 1998), Rodriguez-Maranon et al. (2002) predicted the topology of the MOMP of mouse pneumonitis serovar of C. trachomatis as a porin. In this model, the variable domains (VDs) were located on the outer loops (i.e., exposed on the surface), which is consistent with immunological data (Stephens et al. 1987; Baehr et al. 1988; Su et al. 1988). However, this model was based on theoretical speculation, without confirmation from biochemical experiments. With the assumption that the cysteines were externally exposed, the conserved cysteine 204 residue was put in the transmembrane strand, albeit without any appropriate explanation. It is not clear whether other residues, in addition to the four VDs, are externally exposed when the MOMP conformation is intact.

Without electron diffraction and X-ray crystallography (Walian and Jap 1990; Jap et al. 1991; Jap and Walian 1996) to define the MOMP three-dimensional structure, it has been anticipated that more accurate structural models of MOMP could be proposed on the basis of other well designed biochemical experiments. The development of electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry (MS) methods made it possible to ionize large biomolecules while transferring them to the gas phase, using only small amounts of the samples. ESI and MALDI have therefore become powerful tools in protein analysis and have made mass spectrometry the key technology in the emerging field of proteomics and protein structure study (Fenn et al. 1989; Costello 1999; Mann et al. 2001; Baumann and Meri 2004). Structural studies of MOMP have been hampered by the fact that under native conditions the solubility of this membrane protein is low, and this makes purification of the protein extremely difficult. These limitations preclude the structural analysis of MOMP by using X-ray crystallography, which generally requires significant quantities of crystallized protein. Nevertheless, pursuit of the two-dimensional structure is mandated because identifying the surface-exposed elements and possible transmembrane β-strands of MOMP would provide information for its functional analysis.

In this study, mass spectrometry is applied to study the surface-exposed components of the MOMP of chlamydial EB and to establish the locations of disulfide bonds. A new topological sketch of chlamydial MOMP is proposed. This refined model may be closer to the native conformation of the MOMP than is the previous model.

Results

Immunoaccessible domains of MOMP identified by immuno-dot blot assay and Western blot analysis

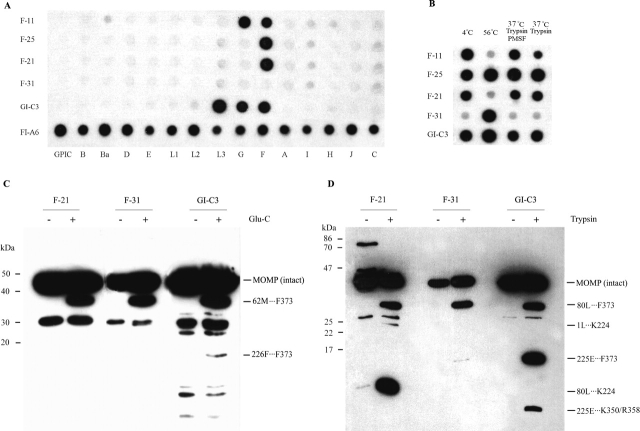

To determine the outer membrane surface-located components of MOMP, we performed immuno-dot blot assay by using intact EBs. Reaction patterns of MAbs in this assay demonstrate the antigenicity of epitopes on the native EB surface. MAb F-11 was bi-specific, recognizing serovars F and G. MAbs F-21 and F-25 were serovar-specific, recognizing serovar F. MAb GI-C3 was subspecies-specific, recognizing serovars F, G, K (not shown in Fig. 1A), and L3. MAb F-31 failed to recognize the determinants on native EBs of different serovars (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Immunoblot and Western blot analysis of intact EBs and endoproteinase-digested EBs of C. trachomatis serovar F. (A) Specificity of MAbs by immuno-dot blot. Viable EBs of each C. trachomatis serovar and guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis (GPIC) were used as antigen(s) in the immuno-dot blot assay. The specificities of MAbs F-11, F-21, F-25, F-31, and GI-C3, which recognize different MOMP epitopes, were tested. MAb FI-A6, which recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS) epitope of all chlamydial serovars and strains, was used as a control. (B) The effect of heat and trypsin treatment on the antigenicity of immunoaccessible epitopes by immuno-dot blot. EBs of C. trachomatis serovar F were incubated at 4°C, heated for 30 min at 56°C, treated with trypsin for 30 min at 37°C or treated with trypsin plus PMSF for 30 min at 37°C, and then reacted with MAbs that recognize different MOMP determinants. (C) Western blot analysis of EBs digested with Glu-C; (D) Western blot analysis of EBs digested with trypsin. EBs of C. trachomatis serovar F digested with endoproteinase Glu-C or trypsin for 30 min at 37°C were used as the test antigens, and EBs incubated in PBS for 30 min at 37°C were used as a control. MAbs F-25, F-31, and GI-C3 were used as probes to detect the proteolytic peptides. Peptide bands corresponding to those recognized by MAbs are indicated by arrows, and the first five amino acids of the N terminus (from N-terminal sequencing) and the deduced C-terminal residues are annotated.

As shown in Figure 1B, purified intact EBs were incubated at 4°C, heated at 56°C, and treated with trypsin or trypsin plus phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, a trypsin inhibitor) for 30 min at 37°C. Five MAbs against epitopes in VDI to VDIV (Table 1) were used as probes to detect the surface-exposed domains (Fig. 1B). Specific determinants of the EBs that had not been heat- or trypsin treated were recognized by MAbs F-11, F-21, F-25, and GI-C3. However, heating destroyed the determinants recognized by MAbs F-11 and F-21 but slightly increased the immunoaccessibility of determinants recognized by MAbs F-25 and GI-C3. The specific determinant was recognized by MAbF-31 after heating only. These data indicate that (1) MOMP epitopes located at VDII, VDIV, and most likely VDI, are surface-exposed under the native conditions; (2) MAbs F-11 and F-21 are conformation-dependent antibodies recognizing native epitopes only; (3) heat treatment alters the conformation of the surface-located MOMP determinants, resulting in failure to be recognized by conformation-dependent antibodies; (4) the epitopes recognized by MAbs F-21 and GI-C3 may become more accessible when its native conformation was altered; and (5) the epitope recognized by MAb F-31, which is located in VDIII, is blocked under the native conditions, and the spatial blockage can be removed during the heat treatment.

Table 1.

Monoclonal antibodies to the MOMP of C. trachomatis serovar F

| MTMP MAb/no. | Reactivity with viable organisms | Location of epitope | Heat response | Trypsin digestion | Antibody specificity response inoculated |

| F 21 | Yes | MOMP VDIIa | S | R | Serovar-specific (F) |

| F 25 | Yes | MOMP VDII 142VNATKP147 | R | R | Serovar-specific (F) |

| F 11 | Yes | MOMP VDI?b | S | S | Serovar-specific (F, G) |

| F 31 | No | MOMP VDIII 225EFPLD229 | R | R | Subspecies-specific (A, B, Ba, D, F, H, I, J, K, L1, L2, L3) |

| GI-C3 | Yes | MOMP VDIVa | R | ND | Group-specific (F, G, K, L3) |

| FI-A6 | Yes | LPS | R | ND | Genus-specific |

S, sensitive; R, resistant; and ND, not done.

a The final mapping was not done.

b Determined by prediction according to the sequence analysis but not by epitope mapping.

Trypsin treatment considerably reduced the antigenicity of MOMP epitope recognized by MAb F-11, slightly diminished signal detection by MAb F-21, and had no effect on the heat-resistant determinants (Fig. 1B). Following the amino acid sequence of the MOMP of serovar F (see Fig. 6), we found that two trypsin cleavage sites (Lys80 and Arg84) are located in VDI. When EBs are subjected to a trypsin digestion, the determinant recognized by MAb F-21 may lose its native conformation and, thereby, become inaccessible. VDII region contains only one lysine residue (Lys146), but this lysine is followed by a proline (Pro147) and is inert to trypsin. As shown in Figure 1B, we observed that both the trypsin-treated sample and its control showed an increase in the signals detected by MAb F-25. This could be unrelated to trypsin digestion but caused by the incubation at 37°C. Given that the VDIV region has no trypsin cleavage sites, trypsin treatment should not cleave the VDIV region. A potential trypsin cleavage site, Lys224, is located in the VDIII region, adjacent to the epitope recognized by MAb F-31 (Table 1). As described above, the VDIII region may be blocked by adjacent strands (possibly by VDIV). The spatial blockage may still exist after the treatment for 30 min at 37°C and therefore prevent the antibody from accessing this region.

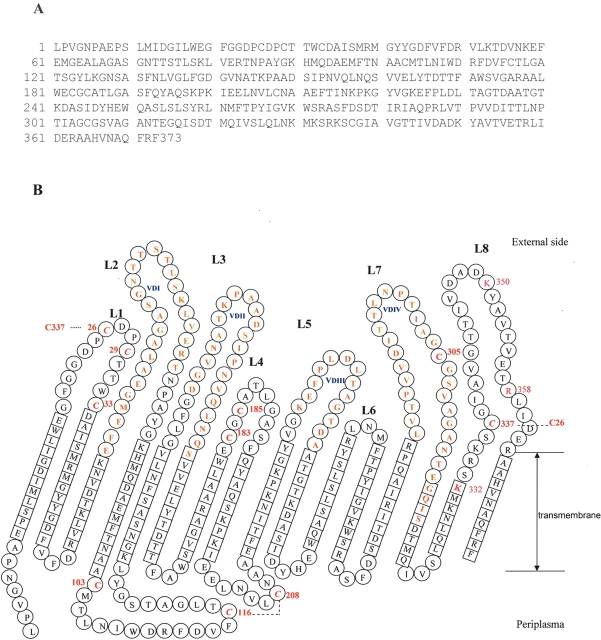

Figure 6.

(A) Overview of the amino acid sequence of MOMP of C. trachomatis serovar F; (B)Topology sketch of MOMP as viewed from the barrel exterior. Residues of the β-strand are indicated by squares. Residues of the loops (L) and turns are in circles. Loops face the outside, while turns face the periplasm. VDI-IV represents the four variable domains of MOMP and is indicated in blue. Residues in the VDs are in bold. The cysteines that possibly form disulfide bonds are indicated in red and italics, and the potential disulfide bridges are shown with dotted lines. Each cystine carries a position number. One-letter codes of amino acids are used.

Enzyme cleavage sites on MOMP identified by immunoblot and N-terminal sequencing

To determine the potential surface-located amino acids, besides those in the four VDs, we carried out brief trypsin digestions, followed by Western blot analyses and protein N-terminal sequencing. Trypsin specifically cleaves at the C-terminal side of arginine or lysine residues and resulted in the estimated 31-kDa, 24-kDa, 17-kDa, 14-kDa, and 11-kDa peptides (Fig. 1C). We also used endoproteinase Glu-C, which can cleave at the C-terminal side of aspartic acid or glutamic acid residues to digest EBs under the same condition, and the generation of 34-kDa and 16-kDa peptides by Glu-C was indicated (Fig. 1D). As shown in the right panel of Figure 1, C and D, trypsin cleavage sites are located between Lys79 and Leu80 in the VDI region and between Lys224 and Glu225 in the VDIII region. Glu-C cleavage sites are located between Glu61 and Met62 in VDI and between Glu225 and Phe226 in VDIII. The treatments with trypsin and Glu-C yielded consistent results.

Enzyme cleavage sites on MOMP analyzed by mass spectrometry

From Western blot analyses of trypsin digestion products, we observed an 11-kDa peptide whose N terminus started from Glu225 and that only reacted with the antibody against a determinant in the VDIV region; this result indicated that there should be some cleavage sites between the end of VDIV and the C terminus of the MOMP primary sequence. Any peptides from the proteolysis that did not contain the VD regions or that had a molecular weight of <6 kDa would be almost impossible to detect by Western blot analysis. To address this limitation, mass spectrometric techniques were applied to analyze the tryptic digestion mixture.

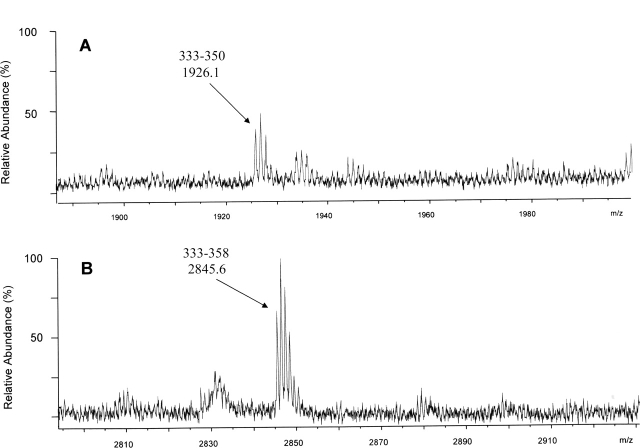

After reverse-phase (RP) HPLC (high-pressure liquid chromatography) separation of the tryptic peptides from the EBs, we observed by MALDI-TOF MS (time-of-flight) two peptides whose mass matched the expected C-terminal sequence of MOMP, and these results therefore confirmed that there are trypsin-accessible sites downstream from the VDIV (Fig. 2A,B). We also identified two peptides matching the calculated masses of Glu59–Lys79 and Glu59–Arg83, consistent with the result of the enzyme-cleavage sites within the VDI from the Western blot analysis and N-terminal sequencing.

Figure 2.

Surface-exposed regions near the C terminus of MOMP, as detected by MALDI-TOF MS. Mass spectra of MOMP peptides, corresponding to residues 333–350 (A) and 333–358 (B) are shown. Reflectron MALDI-TOF MS spectra of individual HPLC fractions from the trypsin digest of intact EBs are shown over the mass ranges m/z 1885–2000 and m/z 2795–2930 Da; cysteines were reduced after digestion and pyridylethylated with 4-vinyl-pyridine. The assignments and monoisotopic masses of fragments are indicated above each peak.

Determination of post-translational modification on cysteine residues

MOMP C. trachomatis serovar F contains 10 cysteines within its 373–amino acid sequence. Previous studies have shown that MOMP may form intramolecule or intermolecule disulfide bonds with itself and with other cysteine-rich proteins, such as 60-kDa outer membrane protein (OMP2) and 9-kDa outer membrane protein (OMP3) (Hatch 1996). However, the disulfide bridges have not been mapped because of the difficulties in purification of membrane proteins and their insolubility.

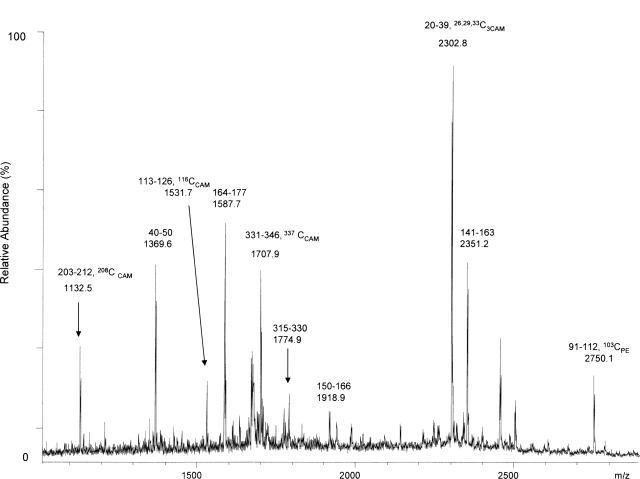

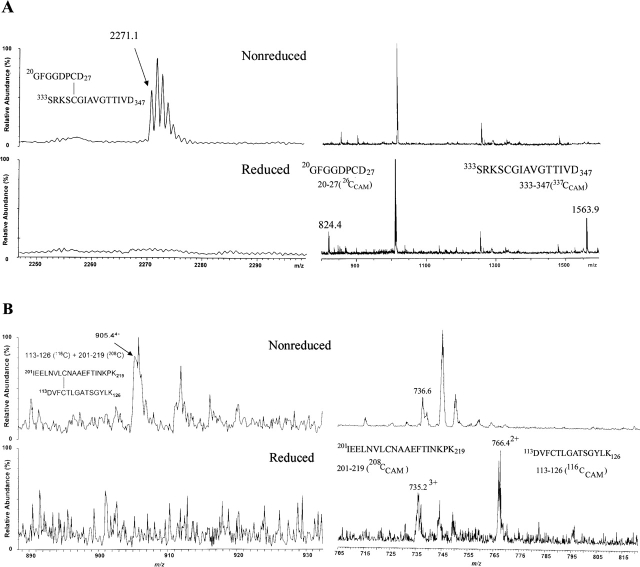

In this study, we identified the cysteines involved in disulfide bonds; these should not be located within the transmembrane region. The purified OMC was digested with a combination of three endoproteinases (trypsin, Asp-N, and Glu-C) in order to achieve the maximum coverage of the whole MOMP sequence. The nonreduced proteins were pyridylethylated with 4-vinyl-pyridine (VP), and this step was followed by reduction and a second modification with iodoacetamide, with the assumption that the initially disulfide-bridged cysteine would be modified only by the latter procedure. The proteolysis products were separated by HPLC and analyzed by mass spectrometry. When OMC was digested with trypsin alone, several MOMP peptides were observed, but cysteine-containing peptides were absent or poorly recovered peptides. We next applied three enzymes (trypsin, Asp-N, and Glu-C) to digest OMC into smaller peptides. The representative fraction from the HPLC separation is shown in Figure 3 with much better definition. Cysteine residues 26, 29, 33, 116, 208, and 337 were alkylated with iodoacetamide. To confirm this result from MALDI-TOF MS analysis, tandem mass spectra were obtained. In the representative tandem mass spectrum shown in Figure 4, cysteine 208 is observed to be alkylated with iodoacetamide. These cysteines appeared as iodoacetamide labeled in the product mixture from the trypsin and chymotrypsin digestion experiments as well. Little signal was obtained from peptides containing cysteines 103, 183, 185, and 305, probably because they are likely within the β-sheets of the transmembrane regions. Next, we showed cysteine 26 and cysteine 337, cysteine 116 and cysteine 208 forming two disulfide bridges by MALDI-TOF MS and ESI MS (Fig. 5A,B). Taken together, these data indicate that cysteines 26, 29, 33, 116, 208, and 337 are on the surface of either the outer or the inner face of the membrane and are not in the transmembrane region (summarized in Table 2).

Figure 3.

Cysteines involved in disulfide bridges, as shown by secondly modified with iodoacetamide. Reflectron MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of one HPLC fraction from the combination of trypsin, Asp-N, and Glu-C triple-enzyme digest of OMC demonstrates modified cysteine containing fragments. CAM indicates carboxymethylation of cysteine by iodoacetamide; PE, to pyridylethylation of cysteine by 4-vinyl-pyridine. The monoisotopic mass and sequence are indicated above each peak.

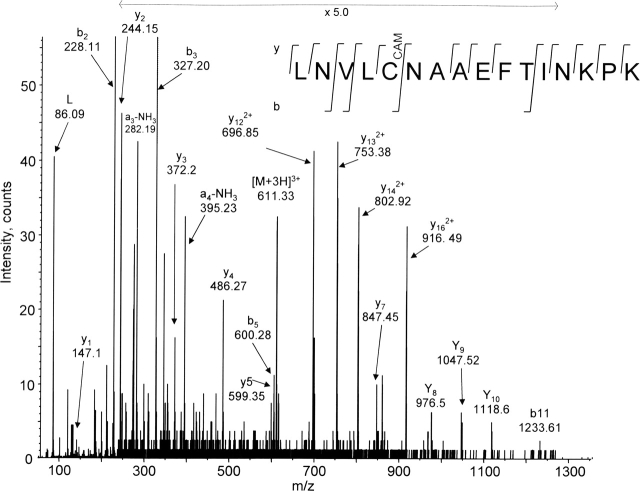

Figure 4.

A representative capillary LC MS/MS spectrum indicating that Cys208 is involved in disulfide bridges. MS/MS fragmentation of the precursor m/z 611.33 (labeled [M+3H]3+) produced the y- and b-ions series from which was determined the sequence of 16 amino acids, including iodoacetamide-alkylated Cys208. Nonreduced OMC was digested with trypsin, Asp-N, and Glu-C triple enzymes, followed by the double cysteine-modification (with intervening reduction) and HPLC separation steps, as detailed in Materials and Methods. CAM indicates carboxymethylation of cysteine by iodoacetamide. The deduced sequence is shown above the spectrum using the one-letter codes for amino acid residues.

Figure 5.

Cys26 and Cys337, Cys116 and Cys208 were found to be involved in disulfide bridges upon comparison of mass spectra of the nonreduced OMC and reduced OMC from the same fraction. Nonreduced OMC was digested with trypsin, Asp- N, and Glu-C triple enzymes, and subsequently was pyridylethylated with VP, followed by HPLC separation of the products (nonreduced fractions). The candidate fractions containing possible disulfide-bridged peptides were reduced and carboxymethylated with iodoacetamide (reduced fractions). (A,top) MALDI-TOF mass spectra from the nonreduced fraction over the mass ranges m/z 2200–2300 and 800–1600; cysteine 26 and cysteine 337 form one disulfide bridge to form the peptide with m/z 2271.3 of [M+H]+ ion. (Bottom) MALDI-TOF mass spectra from the reduced fraction over the mass ranges m/z 2200–2300 and 800– 1600; the two peptides were separated and appeared as iodoacetamide alkylated peptides with m/z 823.4 and m/z 1562.3 of [M+H]+ ions after the fraction was reduced. (B,top) ESI mass spectra from the nonreduced fraction over the mass ranges m/z 890–930 and 705–815. (Bottom) Two peptides, connected by one disulfide bond in the nonreduced fraction, were observed to be iodoacetamide alkylated. Peptides are marked with m/z value, charge state, and corresponding sequences.

Table 2.

Summary of identified major cysteine-containing peptides from multiple-enzyme digestion by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and LC mass spectrometry

| Cysteines | Theoretical [M+H]+ | Experimental [M+H]+ | Cysteine labeled with | Residues | Involvement of disulfide bonds |

| Cys26 | 1422.59 | 1422.62 | IAM | 14–26 | Yes |

| Cys29, 33 | 939.32 | 939.41 | 2IAM | 27–33 | Yes |

| Cys103 | 2603.12 | 2603.18 | VP | 91–111 | No |

| 2750.19 | 2750.20 | VP | 91–112 | ||

| Cys116 | 1678.81 | 1678.79 | IAM | 112–126 | Yes |

| 1531.74 | 1531.85 | IAM | 113–126 | ||

| Cys183, 185 | 2544.20 | 2545.20 | 2IAM | 178–200 | Yes, but seldomly observed |

| Cys208 | 1132.52 | 1132.50 | IAM | 203–212 | Yes |

| 1831.97 | 1831.99 | IAM | 204–219 | ||

| 2203.14 | 2203.12 | IAM | 201–219 | ||

| Cys305 | 2110.00 | 2110.09 | VP | 294–314 | No |

| Cys337 | 1506.74 | 1506.70 | IAM | 336–350 | Yes |

| 1634.83 | 1634.81 | IAM | 335–350 | ||

| 1707.92 | 1707.70 | IAM | 331–346 | ||

| 2425.22 | 2474.40 | IAM | 336–358 |

Nonreduced sample was pyridylethylated with 4-vinyl-pyridine (VP) first and, after reduction, was carboxymethylated with iodoacetamide (IAM).

Two-dimensional model of MOMP

Computational analyses with different algorithms based on β-sheet structures, as described in Materials and Methods, support the idea that MOMP encodes an intrinsic membrane protein bearing potentially 16–18 transmembrane-spanning segments. Alignments using the program FORESST indicated that the characteristics of MOMP strongly resemble the properties of bacterial porins. E. coli LamB (Protein Data Bank [PDB] 1MAL), which has an 18-strand β-barrel, and Rhodobacter capsulatus 3 por (PDB 3POR), with 16 β-sheets, were employed as analogs for the MOMP two-dimensional structure. A refined model of MOMP is shown in Figure 6. The conserved sequences (163 amino acids) are clustered in the β-sheet regions, which represent fewer than half of the total 373 amino acids, and the extramembranous loops and turns are formed by the VDs or regions that contain active cysteine residues. The β-barrel surface containing the nonpolar membrane interior is coated with aliphatic side chains that form a nonpolar ribbon. Interestingly, several polar residues exist in the middle of the β-barrel, forming a polar circle.

Discussion

As the primary candidate for chlamydial vaccine, MOMP has been the subject of intense study for decades. Vaccine preparations based on chlamydial outer membrane protein complexes, which are highly enriched for the MOMP in its native form, have been shown to be protective against chlamydial disease (Tan et al. 1990; Pal et al. 1997). However, experimental vaccines based on denatured or nonnative recombinant MOMP preparations have yielded, at best, only partial protection (Pal et al. 1997), indicating that the native structure of MOMP is important for understanding the molecular basis of chlamydial pathogenesis. In this study, we undertook an investigation of the surface-exposed components of the C. trachomatis MOMP in an attempt to unravel structural details and perhaps portray a more accurate description of the important topological properties of the protein.

Given that our experimental results are not consistent with the model of Rodriguez-Maranon et al. (2002), we present a new model instead. The criteria for the transmembrane residues alignment within β-sheets include the following: (1) The hydrophobic index is >0.5, (2) a minimum of nine residues is needed to span the membrane, and 3) the five constant domains are present on β-strands and the periplasmic turns. The criteria for the external or periplasm loop include the following: (1) The four VDs are positioned on the external surface of the EB, (2) the protease-accessible residues are on the external surface, and (3) cysteines involved in disulfide bridges are paired and present on the same external or periplasmic side.

According to the molecular weight of the tryptic peptides indicated by Western blot analysis, Su et al. (1988) estimated that the trypsin-accessible sites of the B serovar are located in VDII and VDIV, while the MOMP of the L2 serovar was cleaved only at the Lys in VDIV. We showed that trypsin-accessible sites are not located in either VDII or VDIV but—on the basis of results from immuno-dot blot, Western blot analysis, and N-terminal sequencing—are indicated to be in VDI and VDIII in serovar F. Additionally, endoproteinase Glu-C sites are also accessible within both regions. In an effort to find the enzyme cleavage sites that cannot be located by Western blot analysis, mass spectrometry was applied. Our data indicated that there are three more trypsin-accessible sites near the C terminus, at Lys332, Lys350, and Arg358. According to our model, we explain that antibodies can approach VDII and VDIV but not VDIII under native conditions as shown by immuno-dot blot analysis. When the temperature is increased (56°C), the blockage on VDIII is denatured; therefore, the epitope of VDIII is exposed. At 37°C, the enzyme can bypass the blockage and cleave VDIII because it is much smaller than the antibodies. The tryptic treatment for 30 min under 37°C is not able to disturb the barrier blocking the VDIII accessibility by antibody against VDIII (Fig. 1B). The cleavage sites in VDIII were revealed by Western blot analyses (Fig. 1C,D) because of the denaturing condition (such as sample boiling, SDS).

Disulfide bond formation is crucial for the structure and stability of many proteins. In recent years, much progress has been made in understanding how disulfide bonds are formed during protein folding in cells. Disulfides form in the periplasm of prokaryotes (Rietsch and Beckwith 1998) and in the endoplasmic reticulum of eukaryotes (Frand and Kaiser 1999). In prokaryotes, proteins destined for periplasm are synthesized as precursors carrying an N-terminal signal sequence that directs them to the general secretion machinery at the inner membrane. After translocation and signal sequence cleavage, the newly exported mature proteins can form disulfide bridges and are folded and assembled in the periplasm (Miot and Betton 2004).

MOMP possesses a large number of cysteine residues, 8–10, in C. trachomatis. The infectivity of C. trachomatis is reduced by treatment with DTT (Su et al. 1988). We first attempted to identify the cysteines involved in disulfide bonds by using purified OMC treated with two different alkylation reagents to distinguish natively nonreduced and reduced cysteines. Cys208 and Cys337 are clearly involved in disulfide bridges. Cys26–Cys337 and Cys116–Cys208 are likely to form disulfide bonds. Cys103 and Cys305, which are not conserved in different species and serovars, were hard to detect, probably because these cysteines are located in the transmembrane strands.

Cys208 is a conserved cysteine, contrary to the 2002 report of Rodriguez-Maranon, in which this cysteine was considered as a nonconserved cysteine and was included in the transmembrane β-sheet. Our experiments demonstrated that Cys208 is involved in a disulfide bridge, likely formed with Cys116. Cys208 is thus pulled out from the transmembrane strand into the periplasm and faces the same side of the membrane as Cys116. The possibility that Cys116 and Cys208 approach one other and form a disulfide bond is stereochemically reasonable because the two cysteine-containing loops have 9 and 10 amino acids each, and the loop (three amino acids) between two Cys loops is small. In the MOMP case, Cys116 and Cys208 maintained the periplasmic disulfide bond after assembly, while cysteines such as Cys26 and Cys337 were flipped outside and formed a disulfide bond facing the external side. We also observed shuffling of cysteine disulfide bonds when we dealt with MOMP from RB and EB mixtures. This may suggest that the disulfide bonds are dynamic rather than stable and adapt to structural changes during the RB and EB cycle shift.

Among the lysine and arginine residues of C terminus, Lys332, Lys350, and Arg358 were trypsin-accessible; VDIV was surface-exposed; and Cys26 probably formed a disulfide bond with Cys337. All of these data suggest that residues near the C terminus of MOMP form a big loop (L8, 31 residues). Such a long external loop is not exceptional. Porins from the Vibrio-Photobacterium group, for example, have an unusually long loop (L3) (Nikaido 2003). Determination of the structure of porins has shown that transmembrane strands are connected by short “turns” on the periplasmic side, but the “loops” that connect the strands on the external sides are often long (Jap et al. 1991). The longest loop (L3) folds into a barrel, producing a narrowing of the channel called the “eyelet” (Nikaido 2003; Sirtapetawee et al. 2004). The L8 of MOMP (eight basic residues and nine acidic residues) may play a role similar to the eyelet by folding partially back into the channel and interacting with the array of oppositely charged residues to restrict the channel diffusion size.

In the new model, we have also observed the presence of many aromatic amino acid residues at both the outer and the inner interfaces between the bilayer and the aqueous medium, as has been shown for the R. capsulatus porin (Weiss et al. 1991). This phenomenon has been observed in the structure of E. coli OmpF and PhoE porins (Crago and Koronakis 1998). We believe this model provides insight on information of MOMP that will be helpful for investigations of its structure, function, immunogenicity, and antigenicity.

Materials and methods

Chemical and enzymes

Iodoacetamide, VP, ammonium bicarbonate, and sequencing grade endoproteinase Asp-N (P-3303) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. Acetonitrile (ACN), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 2, 5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. All culture media and Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 were provided by GIBCO, Invitrogen Life Technologies. Sequencing grade modified trypsin (catalog no. V5111) was obtained from Promega Co. Sequencing grade endoproteinase Glu-C (catalog no. 1047817) was purchased from Roche Diagnostics. Protein electrophoresis ProtoGel was from National Diagnostics. All other reagents and buffers were of the best quality available commercially.

Chlamydia and growth conditions

C. trachomatis serovar F (strain IC-Cal-3) was propagated in L929 cells in suspension cultures. RPMI medium1640 was supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, 10 μg/mL gentamicin, and 60 μg/mL vancomycin. Chlamydial EB was harvested and purified from the chlamydial-infected host cells at 40 h post-infection by ultracentrifugation using Renograffin gradients as described by Caldwell et al. (1981). Purified EBs were suspended in SPG buffer (0.25 mM sucrose, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 5 mM L-glutamic acid at pH 7.2), aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. The EBs of the following chlamydial serovars or strains were generously provided by Dr. Harlan D. Caldwell (Laboratory of Intracellular Parasites, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIH): C. trachomatis from A/Har-13, B/TW-5, Ba/Ap-2, C/PK-2, D/UW-3, E/Bour, G/ UW-57/Cx, H/UW-4/Cx, I/UW-12/Ur, J/UW-36/Cx, L1/ LGV-440, L2/LGV-434, and L3/LGV-404; C. psittaci from guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis (GPIC) strain 1.

MAbs against the MOMP of C. trachomatis serovar F

MAbs against MOMP of C. trachomatis serovar F were made as described (Zhang et al. 1987). Intact EBs of C. trachomatis serovar F (strain IC-Cal-3) were used as the antigen for MAb generation. Specificity and reactivity of MAbs were determined by immuno-dot blot and Western blot analysis. MAb GI-C3, which reacted with the MOMP of C. trachomatis intermediate-serogroup serovars (F, G, K, and L3) (Zhang et al. 1989), was also used in this study. pJAC264, a plasmid expression vector carrying the E. coli. lamB gene under the control of an inducible tac promoter (a gift from Dr. Hofnung, Institute Pasteur, Paris, France), was employed for epitope mapping. The lamB gene in pJAC264 contains a BamHI site in loop 4 (between Ser153 and Ser154) and presents the inserted peptide sequence at the cell surface (Boulain et al. 1986). E. coli pop6510, a lamB-deficient strain (Boulain et al. 1986), was used as the host for expression of lamB. Bacterial colonies expressing the putative epitopes were identified by colony immunoblot assay by using specific MAbs as probes. The MAbs used in the current study are listed in Table 1, and their specificities are shown in Figure 1A.

Immunoaccessible epitopes by immuno-dot blot assay

Immuno-dot blot assay was performed as described by Zhang et al. (1987). EBs of C. trachomatis serovar F were incubated at 4°C, heated for 30 min at 56°C, treated with trypsin (protein: enzyme ratio of 5:1) for 30 min at 37°C or treated with trypsin (protein:enzyme ratio of 5:1) plus 2 mM PMSF for 30 min at 37°C, and then reacted with MAbs that recognize different MOMP determinants.

Enzyme digestion

Purified EB of C. trachomatis serovar F suspended in SPG buffer was incubated with either trypsin or Glu-C (protein:enzyme ratio of 10:1) for 30 min at 37°C. Trypsin and Glu-C activities were stopped by the addition of mung bean trypsin inhibitor (1:2 ratio of inhibitor and trypsin) or 2 mM PMSF.

Western blot analysis and N-terminal sequencing

Proteolysis products from EB were applied to two 15% SDS-PAGE (Laemmli 1970) gels and, after the electrophoresis, were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore Corp.). EBs, incubated in the same buffer condition without enzymes, were used as the control. One membrane was followed by Western blot analysis (Burnette 1981) using primary antibodies against four VDs of MOMP. The immunofluorescence assay was performed by using an ECL kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The other membrane was stained with Coomassie blue. After comparison of the immunofluorescence to determine the bands that differed between digested and control samples, the equivalent bands from the Coomassie blue-stained membrane were excised and submitted to the Tufts University core facility for N-terminal sequencing.

Purification of OMC

OMC was purified according to the method of Caldwell (Caldwell et al. 1981) with slight modification. Briefly, EB, purified as described above, was incubated with 2% sarkosyl in PBS (pH 7.2) for 30 min at 37°C, and the mixture was centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000g in 4°C. The pellet was collected and resuspended in PBS, (pH 7.2), followed by addition of 1 mg/mL DNase I and 1 mg/mL RNase A to remove DNA and RNA. After centrifugation at 100,000g, the pellet was washed with PBS, and after two more rounds of ultracentrifugation and washing, the pellet was collected as OMC.

Enzyme digestion of purified OMC

OMC was suspended in denaturing buffer (100 mM NH4CO3, 50 mM PBS at pH 7.0). Either trypsin alone or triple-enzyme mix (trypsin, Asp-N, and Glu-C with 1:1:1 ratio of enzyme activity) was added to the OMC solution in 10:1 ratio of protein:enzyme concentration. OMC digestion was carried out for 16 h at room temperature . The enzyme reaction was stopped by immediately freezing the digests at −20°C or subjecting the product mixture to RP-HPLC after the digestion.

Modification of cysteine residues

For samples subjected to mass spectrometry analysis, cysteine residues of MOMP were modified by VP and/or iodoacetamide. In case of trypsin digestion of intact EBs, the digests were reduced with 100 mM DTT for 1 h and pyridylethylated with 1 M VP (Ward 1996) in darkness for 30 min before RP-HPLC separation. The nonreduced proteolytic OMC digests were pyridylethylated with 1 M VP before RP-HPLC separation, half of each RP-HPLC collected fraction was reduced with 20 mM DTT and carboxymethylated again with 100 mM iodoacetamide (IAM) (Aitken and Learmonth 1996) in darkness for half an hour before C18 Ziptip (Millipore) cleanup.

Separation of proteolytic digests by RP-HPLC

Separations of the proteolytic mixtures from intact EB or OMC were carried out using a narrowbore C5 RP-HPLC column (100 × 2.1 mm; 5-μm particle diameter) equipped with a Vydac precolumn. In all cases, solvent A was 0.1% TFA in H2O and solvent B was 0.1% TFA in ACN. The flow rate was adjusted to 200 μL/min, and, after a 10-min washing period, a three-step gradient was applied. The first step was a 10-min gradient from 100% solvent A to 30% solvent B; the second step was raised to 80% solvent B over a period of 40 min, and the third step increased solvent B to 100% over 10 min. Fractions were collected every minute. All the fractions were dried with a speed-vacuum and were used for subsequent mass spectrometric analysis.

Mass spectrometry analysis

MALDI-TOF MS RP-HPLC fractions were analyzed by a Finnigan MAT Vision 2000 or a Bruker Reflex IVMALDI-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with a 337-nm N2 UV laser (Thermo-Finnigan or Bruker Daltonics, respectively). Fractions were resuspended in 50% ACN/0.1% TFA and mixed 1:1 with matrix solution, deposited on the target, and air-dried. The matrices used included DHB or CHCA. Spectra were acquired by summing the signal recorded after 50–200 laser shots.

Capillary LC/MS and capillary LC MS/MS

An liquid chromatograph (LC) Packings Ultimate micropump with Famos autosampler and Switchos multivalve system (Dionex Corp.) coupled to an Applied Biosystems Inc./PE Sciex QSTAR quadrupole orthogonal TOF (QoTOF) mass spectrometer was employed, using information dependent acquisition. Peptide separation was achieved by using a 256-μm ID×20 cm capillary column packed in-house, with Michrom Magic C18 as the stationary phase, using a pressure bomb (Brechbuehler AG). A 100- or 175-min gradient from 98:2 CH3CN:H2O with 0.1% formic acid (FA) and 0.001% TFA to 85:10:5 CH3CN: CH3CHOHCH3:H2O with 0.1% FA and 0.001% TFA was run at 2 μL/min. Eluent was sprayed at 3800–4500 V, and tandem MS data were generated by using multiple collision energies (18, 24, and 30 V) for each selected peptide. Data from capillary LC runs were standardized by using external calibration. A mass selection window of ~2.5–3 Da (dependent on mass value) was used for isolation of the isotopic cluster.

MS data analysis

MALDI-TOF MS data were analyzed with XTOF software (Bruker Daltonics). Capillary LC-MSdata were analyzed with Analyst software (Applied Biosystems). Tandem MS data were analyzed by using three approaches, including batch searches using Mascot (Matrix Science; http://www.matrixscience.com), batch searches with a directed database using ProID software (ABI), and directed database searching of summed tandem spectra from the multiple collision energies of individual multiply charged (2+–5+) ions using PepSea server.

Determination of the two-dimensional model of the MOMP of C. trachomatis serovar F

The basic “homologous extension” modeling approach was used under the assumption that the MOMP protein has a structure of a particular type. Normally, this method begins with finding a homolog (implied by amino acid sequence similarity) to another protein of predetermined three-dimensional (3D) structure. However, in this case, no statistically significant sequence similarity with such a protein was available. Thus, we began under the assumption that MOMP may be a porin membrane protein. This, of course, did not significantly restrict the number of available predetermined structural models, so that a couple of porin structures that satisfied the minimal requirements of length were chosen. Their 3D structures were then stripped of their nonmembrane-crossing loops and other surface subsequence regions and the side chains were removed, as well. These, in turn, formed a scaffold upon, or through, which the MOMP sequence was threaded. This was done largely “by hand.” The process was performed, in so far as possible, to preserve the basic hydrophobic patterns along each of the trans-membrane β-strands, including, when possible, placing the larger or aromatic residues in the same positions as they were located in the original structure(s). In such cases, more than one solution appeared to satisfy these constraints.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. Public Health Service; NI H, grants R01 AI 47853 (Y.X.Z.), P41 RR10888 (C.E.C.), and S10 RR15942 (C.E.C.); and the NSF, grant DBI-0205512 (T.S.).

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051616206.

References

- Aitken, A. and Learmonth, M. 1996. Carboxymethylation of cysteine using iodoacetamide/iodoacetic acid. In The protein protocols handbook (ed. J.M. Walker), pp. 339–340. Humana Press, Totawa, NJ.

- Baehr, W., Zhang, Y.X., Joseph, T., Su, H., Nano, F.E., Everett, K.D., and Caldwell, H.D. 1988. Mapping antigenic domains expressed by Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85: 4000–4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, M. and Meri, S. 2004. Techniques for studying protein heterogeneity and post-translational modifications. Expert Rev. Proteomics 1: 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavoil, P., Ohlin, A., and Schachter, J. 1984. Role of disulfide bonding in outer membrane structure and permeability in Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 44: 479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulain, J.C., Charbit, A., and Hofnung, M. 1986. Mutagenesis by random linker insertion into the lamB gene of Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Gen. 205: 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette, W.N. 1981. “Western blotting”: Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal. Biochem. 112: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, H.D., Kromhout, J., and Schachter, J. 1981. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 31: 1161–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello, C.E. 1999. Bioanalytical applications of mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 10: 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crago, A.M. and Koronakis, V. 1998. Salmonella InvG froms a ring-like multimer that requires the InvH lipoprotein for outer membrane localization. Mol. Microbiol. 30: 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs, K., Freigang, J., Umhau, S., Zeth, K., and Breed, J. 1998. Prediction by a neural network of outer membrane β-strand protein topology. Protein Sci. 7: 2413–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn, J.B., Mann, M., Meng, C.K., Wong, S.F., and Whitehouse, C.M. 1989. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science 246: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand, A.R. and Kaiser, C.A. 1999. Ero1p oxidizes protein disulfide isomerase in a pathway for disulfide bond formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell 4: 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi, H. and Hirai, K. 1992. Proposal of Chlamydia pecorum sp. Nov. for Chlamydia strains derived from ruminants. Inf. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42: 306–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston, J.T., Kuo, C.-C., Campbell, L.A., and Wang, S.-P. 1989. Chlamydia pneumoniae sp. nov. for Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39: 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, T.P. 1996. Disulfide cross-linked envelope proteins: The functional equivalent of peptidoglycan in chlamydiae? J. Bacteriol. 178: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jap, B.K. and Walian, P.J. 1996. Structure and functional mechanism of porins. Physiol. Rev. 76: 1073–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jap, B.K., Walian, P.J., and Gehring, K. 1991. Structural architecture of an outer membrane channel as determined by electron crystallography. Nature 350: 167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H.M., Kubo, A., and Stephens, R.S. 2000. Design, expression and functional characterization of a synthetic gene encoding the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. Gene 258: 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.-C. and Chi, E.Y. 1987. Ultrastructural study of Chlamydia trachomatis surface antigen by immunogold staining with monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 55: 1324–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, M., Hendrickson, R.C., and Pandey, A. 2001. Analysis of proteins and proteomes by mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70: 437– 473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miot, M. and Betton, J.M. 2004. Protein quality control in the bacterial periplasm. Microb. Cell Fact. 3: 4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder, J.W., Hatch, T.P., Kuo, C.-C., Schachter, J., and Storz, J. 1984. Order II: Chlamydiales. In Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, Vol. 1 (eds. N.R. Krieg and J.G. Holt), pp. 729–739. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD.

- Nikaido, H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67: 593–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S., Theodor, I., Peterson, E.M., and De La Maza, L.M. 1997. Immunization with an acellular vaccine consisting of the outer membrane complex of Chlamydia trachomatis induces protection against a genital challenge. Infect. Immun. 65: 3361–3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietsch, A. and Beckwith, J. 1998. The genetics of disulfide bond metabolism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32: 163–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Maranon, M.J., Bush, R.M., Peterson, E.M., Schirmer, T., and de la Maza, L.M. 2002. Prediction of the membrane-spanning β-strands of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia. Protein Sci. 11: 1854–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari, S.H. and Ward, M.E. 1981. Polypeptide composition of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 123: 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter, J. 1999. Infection and disease epidemiology. In Chlamydiae: Intracellular biology pathogenesis and immunity (ed. R.S. Stephens), pp. 139–169. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- Schirmer, T. and Cowan, S.W. 1993. Prediction of membrane-spanning β-strands and its application to maltoporin. Protein Sci. 2: 1361–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirtapetawee, A., Prinz, H., Samosornsuk, W., Ashley, R.H., and Suginta, W. 2004. Functional reconstitution, gene isolation and topology modelling of porins from Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia thailandensis. Biochem. J. 377: 579–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, R.S., Sanchez-Pescador, R., Wagar, E.A., Inouye, C., and Urdea, M.S. 1987. Diversity of Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein genes. J. Bacteriol. 169: 3879–3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, H., Watkins, N., Zhang, Y.-X., and Caldwell, H.D. 1990. Chlamydia trachomatis-host cell interactions: Role of the chlamydial major outer membrane protein as an adhesion. Infect. Immun. 58: 1017–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, H., Zhang, Y.X., Barrera, O., Watkins, N.G., and Caldwell, H.D. 1988. Differential effect of trypsin on infectivity of Chlamydia trachomatis: Loss of infectivity requires cleavage of major outer membrane protein variable domains II and IV. Infect. Immun. 56: 2094–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, A.F. and Kuo, C.-C. 1994. Binding of the glycan of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis to HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 62: 24–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.W., Herring, A.J., Anderson, I.E., and Jones, G.E. 1990. Protection of sheep against Chlamydia psittaci infection with a subcellular vaccine containing the major outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 58: 3101– 3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M. 1996. Pyridylethylation of cysteine residues. In The protein protocols handbook (ed. J.M. Walker), pp. 345–348. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

- Weiss, M.S., Abele, U., Weckesser, J., Welte, W., Schiltz, E., and Schulz, G.E. 1991. Molecular architecture and electrostatic properties of a bacterial proin. Science 254: 1627–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walian, P.J. and Jap, B.K. 1990. Three-dimensional electron diffraction of PhoE porin to 2.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie, S., Ashley, R.H., Longbottom, D., and Herring, A.J. 1998. The major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia psittaci functions as a porin-like ion channel. Infect. Immun. 66: 5202–5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.X., Steward, S.J., Joseph, T., Taylor, H.R., and Caldwell, H.D. 1987. Protective monoclonal antibodies recognize epitopes located on the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Immunol. 183: 575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.X., Steward, S.J., and Caldwell, H.D. 1989. Protective monoclonal antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis serovar- and serogroupspecific major outer membrane protein determinants. Infect. Immun. 57: 636–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]