Abstract

We report here the construction of a mutant version of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase (AP) in which the active site Ser was replaced by Thr (S102T), in order to investigate whether the enzyme can utilize Thr as the nucleophile and whether the rates of the critical steps in the mechanism are altered by the substitution. The mutant AP with Thr at position 102 exhibited an ∼4000-fold decrease in k cat along with a small decrease in K m. The decrease in catalytic efficiency of ∼2000-fold was a much smaller drop than that observed when Ala or Gly were substituted at position 102. The mechanism by which Thr can substitute for Ser in AP was further investigated by determining the X-ray structure of the S102T enzyme in the presence of the Pi (S102T_Pi), and after soaking the crystals with substrate (S102T_sub). In the S102T_Pi structure, the Pi was coordinated differently with its position shifted by 1.3 Å compared to the structure of the wild-type enzyme in the presence of Pi. In the S102T_sub structure, a covalent Thr-Pi intermediate was observed, instead of the expected bound substrate. The stereochemistry of the phosphorus in the S102T_sub structure was inverted compared to the stereochemistry in the wild-type structure, as would be expected after the first step of a double in-line displacement mechanism. We conclude that the S102T mutation resulted in a shift in the rate-determining step in the mechanism allowing us to trap the covalent intermediate of the reaction in the crystal.

Keywords: X-ray crystallography, mutagenesis, side chain conformation, covalent intermediate, rate-determining step

Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1) is a metalloenzyme that catalyzes the nonspecific hydrolysis of phosphomonoesters to an alcohol and inorganic phosphate (Pi). The enzyme is a dimer of two identical polypeptide chains, each of which contains 449 amino acids and two Zn2+ and one Mg2+ (Kim and Wyckoff 1989; Stec et al. 2000). The two zinc sites (Zn1 and Zn2) are 4 Å apart, and the single magnesium site is located 5 Å from Zn2 and 7 Å from Zn1. In the structure of the wild-type noncovalent E•Pi complex (PDB code 1ALK; Kim and Wyckoff 1989), Pi is bound in the active site by interactions with the two zinc atoms and is also positioned in the active site through interactions with the guanidinium nitrogens of Arg166, the backbone nitrogen of Ser102, and a water-mediated interaction with Lys328.

The catalytic mechanism for the alkaline phosphatase reaction was proposed in 1991 and revised in 2000 (Kim and Wyckoff 1991; Stec et al. 2000). The reaction proceeds through a series of four steps: The enzyme binds the substrate to form a noncovalent complex (E•ROP); the deprotonated Ser102 hydroxyl group attacks the phosphorus of the substrate to form a covalent serine–phosphate intermediate (E–Pi) (Schwartz and Lipmann 1961; Murphy et al. 1997); a hydroxide ion coordinated to Zn1 attacks the phosphorus to form a noncovalent enzyme–phosphate complex (E•Pi); and finally, Pi is released, reforming the free enzyme. The rate-determining step of the reaction is pH dependent; at acidic pH, the hydrolysis of the covalent E–P complex is rate-limiting, while under basic conditions the rate-limiting step becomes the dissociation of Pi from the E•Pi noncovalent complex (Hull et al. 1976; Gettins and Coleman 1983).

In a variety of enzymes, Ser and Thr can often be interchanged for many catalytic functions, due to their structural similarity. Some hydrolytic enzymes, such as the asparaginases (Swain et al. 1993; Palm et al. 1996), the proteasome catalytic subunit (Löwe et al. 1995), and aspartyl glucosaminidase (Oinonen et al. 1995), use Thr as a nucleophile instead of Ser. These enzymes have a catalytic mechanism similar to that of the serine proteases, involving the formation of a covalent intermediate. The activation of a Thr nucleophile is different from a Ser nucleophile. Thr is typically activated by a primary amino group from the side chain of Lys or the N-terminal amino acid whereas Ser is activated as part of a catalytic triad.

Although there are no significant chemical differences between the Oγ atoms of Thr and Ser, the side chains of these residues differ substantially in available conformations and size. The side chain of Thr may have an advantage in certain cases, in that the Cγ could help to exclude water from the active site (Dodson and Wlodawer 1998). Gijsbers et al. (2001) have also pointed out the structural and catalytic similarities between alkaline phosphatase and nucleotide pyrophosphatases/phosphodiesterases that utilize a Thr nucleotide in the reaction. Therefore, in this work we construct a mutant version of alkaline phosphatase that has the active site Ser replaced by Thr in order to investigate whether the enzyme can function with a Thr nucleophile. We combine functional characterization of the S102T alkaline phosphatase with two X-ray crystal structures (in the presence Pi and substrate) to understand how Thr functions as a catalytic group in the active site of alkaline phosphatase.

Results and Discussion

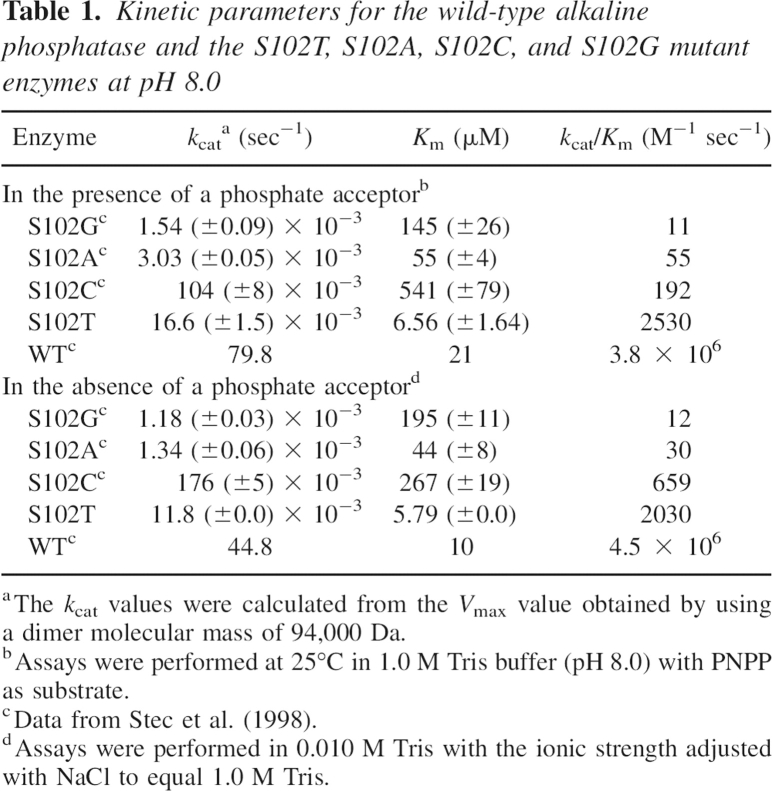

Steady-state kinetics of the S102T alkaline phosphatase

The replacement of Ser102 by Thr resulted in a mutant alkaline phosphatase that retained catalytic activity although at reduced levels (Table 1). In the presence of a phosphate acceptor, Tris, the net reaction rate observed is the sum of hydrolysis and transphosphorylation. Under these conditions, the k cat and K m values for the S102T enzyme decreased 4800-fold and 3.2-fold, respectively, compared to the corresponding values for the wild-type enzyme (Stec et al. 1998), resulting in a 1500-fold decrease in the k cat/K m ratio. In the absence of a phosphate acceptor, the rate observed is solely hydrolysis. Under these conditions, the k cat and K m values for the S102T enzyme decreased 3800-fold and 1.7-fold, respectively, compared to the wild-type enzyme (Stec et al. 1998), resulting in a 2200-fold reduction in the k cat/K m ratio.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for the wild-type alkaline phosphatase and the S102T, S102A, S102C, and S102G mutant enzymes at pH 8.0

Although the S102T enzyme is much less active than the wild-type enzyme, it is far more active than the previously reported S102C, S102A, and S102G enzymes, either in the presence or in the absence of a phosphate acceptor (Stec et al. 1998). In the presence of a phosphate acceptor, the k cat/K m ratio of the S102T enzyme was 230-fold, 46-fold, and 13-fold higher than the corresponding values for the S102G, S102A, and S102C enzymes, respectively. In the absence of a phosphate acceptor, the k cat/K m ratio was 169-fold, 68-fold, and 3.1-fold higher. When the data for the S102T enzyme reported here are combined with data for other mutations at position 102 (Stec et al. 1998), the catalytic activity of these enzymes in decreasing activity is found to be WT > S102T > S102C > S102A > S102G.

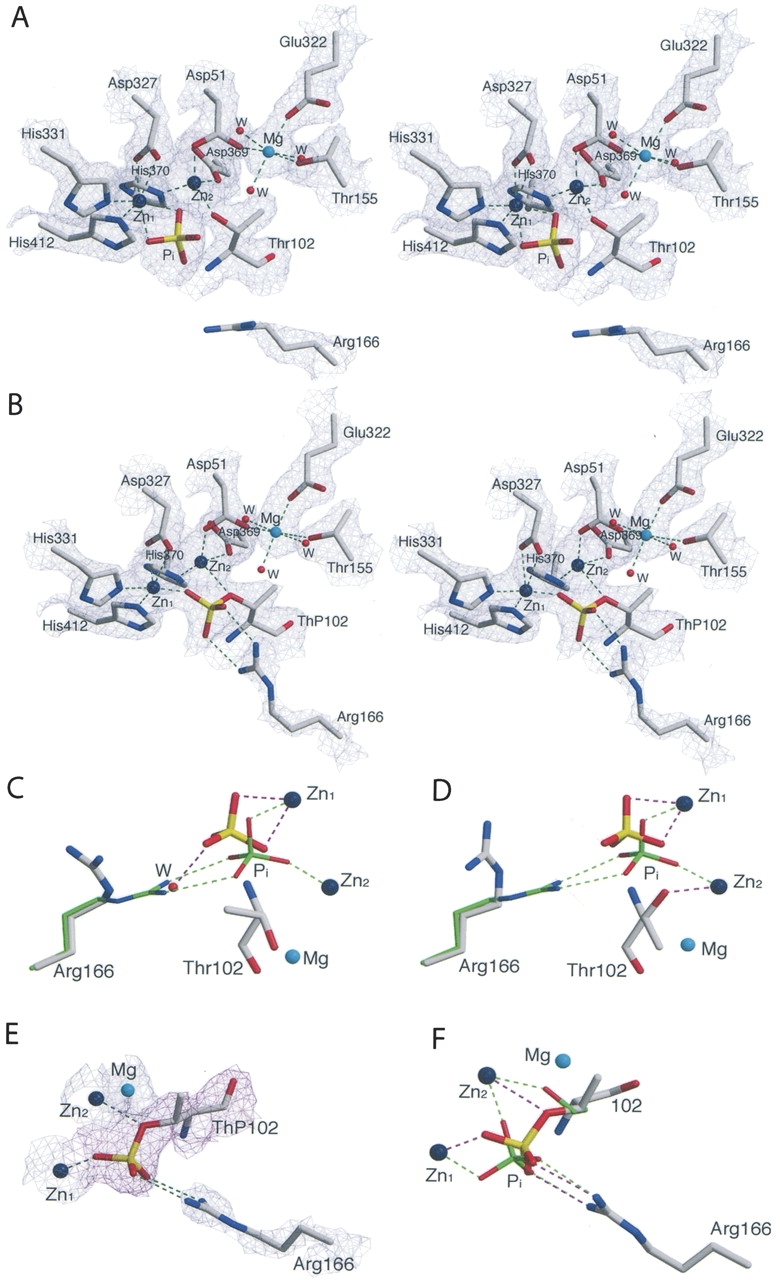

Structure of the S102T_Pi enzyme

The structure of the S102T in the presence of Pi was determined in order to elucidate the structure of the noncovalent E•Pi complex. Crystals of the S102T enzyme were soaked in a phosphate-containing buffer for 15 min before data collection. Analysis of 2F o –F c and F o –F c electron density maps indicated that the active sites in the S102T_Pi structure differed significantly from the corresponding wild-type structure (WT_Pi), particularly near the phosphate binding sites. The active site of the S102T_Pi structure is shown in Figure 1A. The side chain methyl group of Thr102 restricts the available conformations of the Thr side chain, so that the hydroxyl group cannot rotate as freely as was observed for the Ser hydroxyl group. The orientations of the Thr side chain are limited to three χ values: −60°, +180°, and +60° (Daley and Sykes 2003). In the S102T_Pi structure, the side chain of Thr102 adopts different conformations in the A-chain and B-chain. In the A-chain, the side chain of the Thr102 adopts the χ = −60° conformation, while in the B chain it adopts the χ = +180° conformation. In chain A, the methyl group of Thr102 points toward the midpoint of the two hydrogen bonds that form between a phosphorus oxygen and the side chain of the Arg166 in the WT_Pi structure (see Fig. 1C). If one compares the position of Thr102 in the S102T_Pi structure with the position of Pi and Arg166 in the WT_Pi structure, the distance between the methyl group and the phosphorus oxygen is 2.2 Å, while the distance between the methyl group and the Arg166 NH1 is 2.8 Å. This close contact between a hydrophobic group and two hydrophilic groups is energetically unfavorable, resulting in the displacement of Pi by 1.3 Å in the S102T_Pi structure, compared to its position in the WT_Pi structure. The new position prevents the Pi from forming two hydrogen bonds with Arg166, important interactions for the stabilization of Pi in the active site (Chaidaroglou et al. 1988; Chen et al. 1992). In addition, in the S102T_Pi structure, the Pi is stabilized by two coordinate bonds with Zn1, but has one fewer coordinate bond with Zn2.

Figure 1.

(A) Stereoview of the active site of the S102T_Pi structure. Shown is the 2F o –F c electron density map for the A chain (1.2 σ). The side chain of the Thr102 are in the χ = −60° conformation). Water molecules are shown as red spheres and zinc and magnesium atoms as large dark blue and cyan spheres. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds. (B) Stereoview of the 2F o –F c electron density map for the B chain of S102T_sub (1.2 σ). (C) Comparison of Arg166 and Pi in the active sites of the S102T_Pi structure (elemental colors, thick lines) and the WT_Pi structure (PDB code 1ED8; Stec et al. 2000; green, thin) in the A chain and in the B chain (D). Ligands around the metals are not shown. (E) Active site of the S102T_sub structure. The Arg166 and metals are overlaid on the 2F o –F c electron density map (blue) shown contoured at 1.2 σ. The ThP102 is overlaid on the F o –F c electron density map (magenta) shown contoured at 1.5 σ. (F) Comparison of Pi and Ser102 (ThP102) in the active site of the S102T_sub structure (elemental colors, thick lines) and the WT_Pi (green, thin) structure. Ligands around the metals are not shown. Figures were prepared using MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991).

In chain B of the S102T_Pi structure, the hydroxyl group of Thr102 forms a direct coordinate bond with Zn2, preventing the Pi from making a coordinate bond with Zn2 (see Fig. 1D). Pi makes two coordinate bonds with Zn1, but does not interact with Arg166, exhibiting displacement of 1.1 Å compared to its position in the WT_Pi structure.

The S102T_sub structure—Trapping the covalent E–Pi intermediate

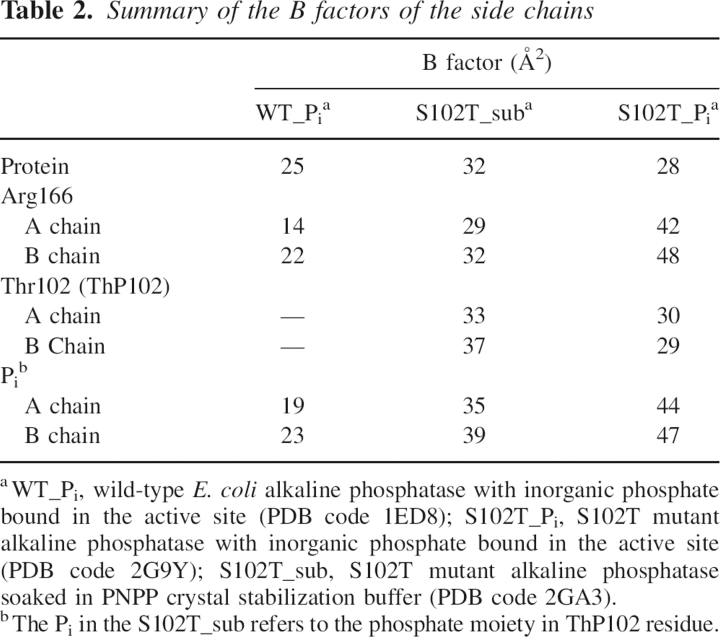

In an attempt to determine the structure of the alkaline phosphatase E•S complex, the X-ray structure of the S102T enzyme was determined using crystals of the S102T enzyme that were frozen after being soaked for a short time in buffer containing the substrate, p-nitrophenol phosphate. The 2.2 Å S102T_sub structure was refined to a R factor/R free of 0.192/0.229 in the I222 space group. In the active site of this structure, the 2F o –F c and F o –F c electron density maps showed continuous density between the phosphorus and the Oγ of the Thr102, with a P–O bond distance of 1.6 Å in both the A and B chains (see Fig. 1B,E). The average distance of a P–O covalent bond is 1.7 Å. These two observations indicate that the structure was not of the E•S complex, but rather of the covalent E–Pi complex. To confirm this hypothesis, a phosphothreonyl residue (ThP102) was modeled into the active sites of both the A and B chains. The S102T_sub structure was then further refined with Thr102 replaced by ThP102. In the S102T_sub structure the active sites of the A and B chains are virtually identical. The average B factor for the side chain of ThP102 was 34.7 Å2, close to the average B factor for the side chains of the entire protein, 32.3 Å2 (Table 2). In the refined structure, one of the phosphate oxygens of ThP102 was coordinated to Zn1 while another oxygen was coordinated to Zn2. The stereochemistry of the phosphorus in the S102T_sub structure is inverted compared to the stereochemistry of the Pi in the structure of the wild-type noncovalent E•Pi structure, as would be expected after the first step of a double in-line displacement mechanism (see Fig. 1F).

Table 2.

Summary of the B factors of the side chains

The rate of hydrolysis of the covalent E–Pi complex is greatly reduced

In the proposed mechanism for reaction of native alkaline phosphatase, a water molecule activated by Zn1 acts as the nucleophile in the second in-line displacement step: the hydrolysis of the covalent E–P complex to form the E•Pi noncovalent complex. In a previously determined structure of an alkaline phosphatase mutant in which histidine 331 was replaced by glutamine, the covalent Ser–Pi complex was stabilized (Murphy et al. 1997). In this structure, a water molecule was observed coordinated to Zn1, positioned optimally for in-line displacement of the Pi. However, in the S102T_sub structure, no water molecule was observed in the same position in either the A- or B-chain active sites. The methyl group of the ThP102 points toward the hydroxyl group of Thr155. Because of the repulsion force between a hydrophobic and hydrophilic group, the hydroxyl of Thr155 in the threonine–phosphate complex is displaced away from the active site, when compared to the covalent serine–phosphate complex (PDB code 1HJK; Murphy et al. 1997). The hydroxyl group of Thr155 is shifted 1.2 Å and 0.7 Å away from the active site in the A and B chains, respectively. This movement changes the active site geometry and may be the reason for the weaker binding of the nucleophilic water molecule, which in turn, results in the reduced rate of hydrolysis observed for the S102T enzyme as compared to the wild-type enzyme.

Arg166 is involved in transition state stabilization and the release of the Pi

Previous studies have suggested that Arg166 has two functions in the catalytic mechanism. First, it assists in substrate binding and the release of Pi and second, it stabilizes the charge on the covalent E–P intermediate and the trigonal bipyramidal transition state during the reaction (Chaidaroglou et al. 1988; Kim and Wyckoff 1991). Arg166 was observed to occupy different positions in the S102T_sub and S102T_Pi structures. In both chains of the S102T_sub structure, the guanidinium group of the Arg166 interacts with the phosphate moiety of ThP102 (see Fig. 1F), helping to stabilize the covalent E–Pi intermediate. In contrast, in both chains of the S102T_Pi structure, Arg166 rotates to a new position away from the Pi binding pocket. In this conformation Arg166 forms two fewer hydrogen bonds with Pi than are observed in the WT_Pi structure (see Fig. 1C,D). The loss of these interactions results in a dramatic increase in the average B factor of the Arg166 side chain to 44.9 Å2, an ~60% increase compared to the average B factors of the protein (Table 2). This significant increase in the average B factor of Arg166 side chain suggests that this side chain has considerably more flexibility in the S102T_Pi structure. In this structure, a water molecule interacts with Pi in the position normally occupied by Arg166 in the WT_Pi structure. However, the electron density for this water is weak (1.2 σ), and there is no water at the equivalent position in chain B. With the loss of the interactions between Pi and Arg166, the B factors for the Pi are dramatically increased compared to the values observed for Pi in the wild-type structure (WT_Pi) (Table 2).

Previous studies of a mutant alkaline phosphatase in which Asp101 was converted to Ser have shown that increased flexibility of the Arg166 side chain correlates with a faster dissociation of Pi and a high rate of catalysis (Chen et al. 1992). For the wild-type enzyme, Arg166 is positioned rigidly in a hydrogen bonding network that includes two hydrogen bonds with Pi, one with Asp101 and two with a water molecule (Kim and Wyckoff 1991; Stec et al. 2000). However, in the S102T_Pi structure, there is a repulsion between the methyl group of Thr102 and Pi, resulting in the inability of Pi to bind in the same position observed in the wild-type enzyme. The Pi shifts position until it is restabilized by Zn2. This positional shift of the Pi breaks the hydrogen bonding network of the active site, especially the part involving Arg166. Without these interactions, Arg166 becomes unstable in the position observed in the WT_Pi structure and therefore moves to a more stable position. Both the side chain of Arg166 and Pi have enhanced mobility in this structure, which results in a weakening of affinity for Pi and a faster release of the Pi from the noncovalent E•Pi complex.

Conclusions

Our ability to trap the covalent E–Pi intermediate in the S102T_sub structure indicates that the rate-determining step in the mechanism has changed for the S102T enzyme. In the case of the S102T enzyme, hydrolysis of the covalent E–Pi intermediate now becomes slow relative to release of Pi from the noncovalent E•Pi complex. Thus, in the S102T enzyme the chemical step of hydrolysis of the E–Pi complex becomes rate limiting, thereby allowing us to trap the covalent intermediate in the crystal.

The crystal structures of the S102T_sub and S102T_Pi enzymes suggest the manner in which the rate-determining step in the mechanism was changed by the mutation of Ser102 to Thr. The methyl group of Thr102 induces changes in the positions of active site residues, resulting in a weaker binding of the water molecule that acts as the nucleophile in the second step in the mechanism. This reduced availability of the entering nucleophile results in a significant decrease in the rate of the hydrolysis of the E–P covalent complex. Since the release of Pi is the rate-determining step for wild-type enzyme at alkaline pH, a slower hydrolysis rate of the E–P complex results in a shift in the rate-determining step from the dissociation of Pi from the E•Pi noncovalent complex to the hydrolysis of E–P covalent complex in the S102T enzyme. The reduced affinity of the catalytic water explains the ∼2000-fold decrease of the enzyme activity of the S102T enzyme as compared to the wild-type enzyme.

This S102T mutation in alkaline phosphatase has consequences that are similar to the Glu to Asp mutation in the active sites of triosephosphate isomerases. In both cases while the overall chemical mechanism is retained, the mutation changes the relative free energy of the transition states of the individual steps and results in a different rate-determining step (Raines et al. 1986).

Materials and methods

Materials

Ampicillin, magnesium chloride, zinc chloride, sodium chloride, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, EDTA, sucrose, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and p-nitrophenyl phosphate were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Tris and enzyme grade ammonium sulfate were purchased from ICN Biomedicals. Tryptone and yeast extract were obtained from Difco Laboratories. The oligonucleotides required for site-specific mutagenesis and sequencing were obtained from Operon Technologies. The QuikChange Mutagenesis kit was supplied by Stratagene. Kits for plasmid isolation and purification were supplied by Qiagen. DNA grade agarose was from Fisher. Protein Assay Dye and Source 15Q strong anion-exchange resin were obtained from Bio-Rad. Crystal cryo-mounting loops were from Hampton Research.

Construction of the S102T alkaline phosphatase by site-specific mutagenesis

The S102T mutation was introduced in the phoA gene using the procedure outlined by Stratagene in the QuikChange Mutagenesis kit protocol. The entire gene was sequenced to ensure that no other mutations had been introduced during the mutagenesis. The final plasmid containing the S102T mutation in the phoA gene was designated pEK625.

Expression of the S102T alkaline phosphatase

E. coli SM547 [Δ(phoA-phoC), phoR, tsx::Tn5, Δlac, galK, galU, leu, strr] was used as the host strain for the expression of the S102T alkaline phosphatase. Since the chromosomal phoA gene was deleted from the strain, all the alkaline phosphatase produced is expressed from the phoA gene on the plasmid. The mutation in the phoR regulatory gene results in constitutive synthesis of alkaline phosphatase.

Purification of the S102T alkaline phosphatase

The S102T enzyme was isolated from the SM547/pEK625 plasmid/strain combination by the method previously described (Chaidaroglou et al. 1988). The purity of the enzyme was checked by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Laemmli 1970). The Bio-Rad version of Bradford's dye-binding assay was used to determine protein concentrations using the wild-type alkaline phosphatase as the standard (Bradford 1976).

Determination of enzymatic activity

Phosphatase activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 25°C utilizing p-nitrophenyl phosphate as substrate by monitoring the release of p-nitrophenylate at 410 nm (Garen and Levinthal 1960). The sum of the hydrolase and transferase activities was determined using 1.0 M Tris as the phosphate acceptor. The hydrolase activity was measured using 0.010 M Tris as the buffer. The ionic strength of the two Tris buffers was maintained constant using NaCl.

Crystallization

The vapor diffusion method was used to crystallize the enzyme using hanging drops of 2 μL. The enzyme solution was dialyzed against a protein-stabilization buffer of 100 mM Tris (pH 9.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.01 mM ZnCl2, and 0.85 M (NH4)2SO4 before being concentrated to ∼40 mg/mL. Within ∼1 mo, crystals formed in the drops with ammonium sulfate concentrations between 2.0 M and 2.2 M. Crystal sizes varied from 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.1 mm3 to 1.2 × 0.6 × 0.3 mm3.

Crystal mounting and data collection

Crystals were initially transferred into a crystal stabilization buffer composed of 3.0 M (NH4)2SO4, 100 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM ZnCl2 for at least 24 h. A 0.3 × 0.25 × 0.2 mm3 crystal was soaked in a p-nitrophenylphosphate (PNPP) crystal stabilization buffer (10 mM PNPP, 3.0 M (NH4)2SO4, 100 mM Tris, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ZnCl2 at pH 7.5) for 15 min before it was soaked into a mixture containing 80% p-nitrophenyl phosphate crystal stabilization buffer and 20% glycerol for 1 min (S102T_sub crystal). Another 0.2 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm3 crystal was first soaked in a Pi crystal stabilization buffer (2 mM NaH2PO4, 3.0 M (NH4)2SO4, 100 mM Tris, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ZnCl2 at pH 7.5) for 15 min before it was soaked into a mixture of 80% Pi crystal stabilization buffer and 20% glycerol for 1 min (S102T_Pi crystal). Crystals were picked up in cryo-loops and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

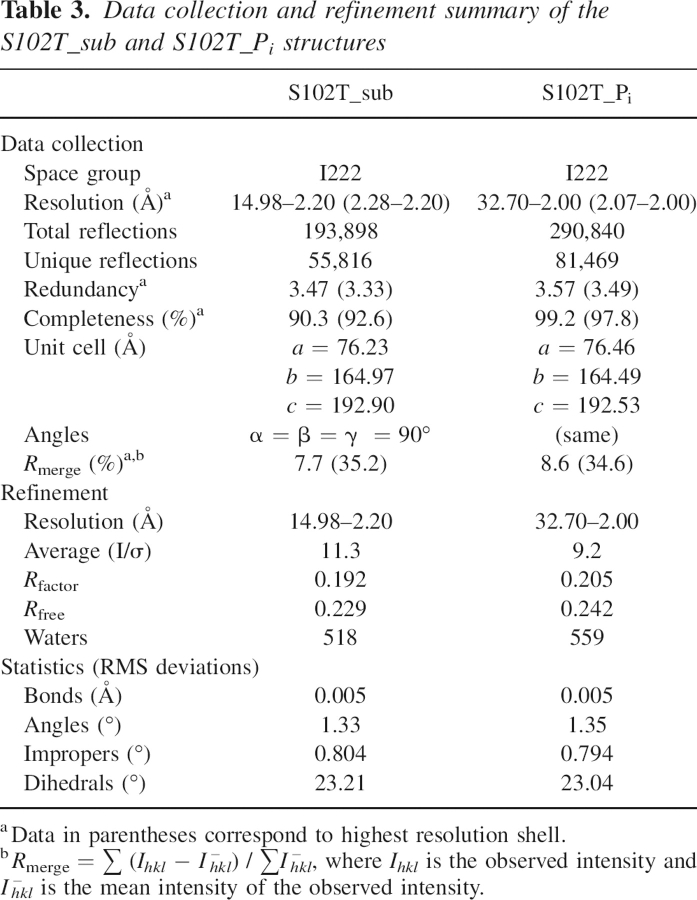

The diffraction data were collected at the Crystallographic Facility in the Chemistry Department of Boston College, using a Rigaku RU-200 rotating anode generator, operating at 50 kV and 100 mA, equipped with a Rigaku/MSC R-axis IV++ detector. Diffraction data were collected to 2.20 Å and 2.00 Å, respectively, for the S102T_sub and S102T_Pi crystals (Table 3). The data sets were integrated, scaled, and averaged by using d*TREK (Rigaku/MSC) (Pflugrath 1999).

Table 3.

Data collection and refinement summary of the S102T_sub and S102T_Pi structures

Structure refinement

The initial models for both the S102T_sub and the S102T_Pi structures were the coordinates of wild-type E. coli alkaline phosphatase with Co2+ in all the metal sites determined to 1.60 Å (PDB code 1Y6V; Wang et al. 2005). This initial coordinate was chosen because the S102T structures are in the same space group I222 and have almost identical unit cell dimensions. Before refinement, all ligands and waters were removed from the model and the Ser102 residue was replaced by Thr in XtalView (McRee 1999). Refinements were carried out using the Crystallography & NMR System (CNS) (Brunger et al. 1998). After the first rigid body refinement, simulated annealing (Brunger et al. 1997), energy minimization, and B-factor refinement, initial maps were inspected and manual rebuilding was performed in XtalView. After each round of refinement, R free was used to avoid overfitting and the F o –F c electron density map was visually inspected for alternate positions (Kleywegt and Brunger 1996). When the R factor fell below 25%, waters were added on the basis of peaks in the F o –F c electron density maps that were at or above the 3σ level, and were checked and retained only when they could be justified by hydrogen bonding interactions. With approximately 520 and 560 waters, the S102T_sub and the S102_Pi structures were refined to an R factor/R free of 19.2%/22.9% and 20.5%/24.2% at a resolution of 2.20 Å and 2.00 Å, respectively (see Table 3).

Stereochemical quality of the two structures was determined from the Ramachandran plot using PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993). Both structures have more than 90% of the residues within the most favored region. None of the active site residues were in disallowed regions. The details of data processing and refinement statistics for both structures are reported in Table 3. The atomic coordinates of the S102T_Pi and S102T_sub structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as entries 2G9Y and 2GA3, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by Grant GM42833 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Evan R. Kantrowitz, Department of Chemistry, Merkert Chemistry Center, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA 02467, USA; e-mail: evan.kantrowitz@bc.edu; fax: (617) 552-2705.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062351506.

Abbreviations: PNPP, p-nitrophenylphosphate; S102T, the mutant version of E. coli alkaline phosphatase with Ser102 replaced by Thr; WT_Pi, wild-type E. coli alkaline phosphatase with inorganic phosphate bound in the active site (PDB code 1ED8); S102T_Pi, S102T mutant alkaline phosphatase with inorganic phosphate bound in the active site (PDB code 2G9Y); S102T_sub, S102T mutant alkaline phosphatase soaked in PNPP crystal stabilization buffer (PDB code 2GA3).

References

- Bradford, M.M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Rice, L.M. 1997. New applications of simulated annealing in X-ray crystallography and solution NMR. Structure 5: 325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S. et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54: 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaidaroglou, A., Brezinski, J.D., Middleton, S.A., Kantrowitz, E.R. 1988. Function of arginine in the active site of Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry 27: 8338–8343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Neidhart, D., Kohlbrenner, W.M., Mandecki, W., Bell, S., Sowadski, J., Abad-Zapatero, C. 1992. 3-D structure of a mutant (Asp101 → Ser) of E. coli alkaline phosphatase with higher catalytic activity. Protein Eng. 5: 605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley, M.E. and Sykes, B.D. 2003. The role of side chain conformational flexibility in surface recognition by Tenebrio molitor antifreeze protein. Protein Sci. 12: 1323–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, G. and Wlodawer, A. 1998. Catalytic triads and their relatives. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23: 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garen, A. and Levinthal, C. 1960. Purification and characterization of alkaline phosphatase. Biochim. . Biophys. Acta 38: 470–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettins, P. and Coleman, J.E. 1983. 31P nuclear magnetic resonance of phosphoenzyme intermediates of alkaline phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 408–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsbers, R., Ceulemans, H., Stalmans, W., Bollen, M. 2001. Structural and catalytic similarities between nucleotide pyrophosphatases/phosphodiesterases and alkaline phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 1361–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull, W.E., Halford, S.E., Gutfreund, H., Sykes, B.D. 1976. 31P nuclear magnetic resonance study of alkaline phosphatase: The role of inorganic phosphate in limiting the enzyme turnover rate at alkaline pH. Biochemistry 15: 1547–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.E. and Wyckoff, H.W. 1989. Structure of alkaline phosphatase. Clin. Chim. Acta 186: 175–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.E. and Wyckoff, H.W. 1991. Reaction mechanism of alkaline phosphatase based on crystal structures: Two-metal ion catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 218: 449–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt, G.J. and Brunger, A.T. 1996. Checking your imagination: Application of the free R value. Structure 4: 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24: 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S., Thornton, J.M. 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26: 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Löwe, J., Stock, D., Jap, B., Zwickl, P., Baumeister, W., Huber, R. 1995. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the Archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 Å resolution. Science 268: 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee, D.E. 1999. XtalView/Xfit—A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J. Struct. Biol. 125: 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.E., Stec, B., Ma, L., Kantrowitz, E.R. 1997. Trapping and visualization of a covalent enzyme–phosphate intermediate. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4: 618–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oinonen, C., Tikkanen, R., Rouvinen, J., Peltonen, L. 1995. Three-dimensional structure of human lysosomal aspartylglucosaminidase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2: 1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm, G.J., Lubkowski, J., Derst, C., Schleper, S., Rohm, K.H., Wlodawer, A. 1996. A covalently bound catalytic intermediate in Escherichia coli asparaginase: Crystal structure of a Thr-89-Val mutant. FEBS Lett. 390: 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugrath, J.W. 1999. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55: 1718–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines, R.T., Sutton, E.L., Straus, D.R., Gilbert, W., Knowles, J.R. 1986. Reaction energetics of a mutant triosephosphate isomerase in which the active-site glutamate has been changed to aspartate. Biochemistry 25: 7142–7154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J.H. and Lipmann, F. 1961. Phosphate incorporation into alkaline phosphatase of E. coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 47: 1996–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec, B., Hehir, M.J., Brennan, C., Nolte, M., Kantrowitz, E.R. 1998. Kinetic and X-ray structural studies of three mutant E. coli alkaline phosphatases: Insights into the catalytic mechanism without the nucleophile Ser-102. J. Mol. Biol. 277: 647–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec, B., Holtz, K.M., Kantrowitz, E.R. 2000. A revised mechanism of the alkaline phosphatase reaction involving three metal ions. J. Mol. Biol. 299: 1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain, A.L., Jaskolski, M., Housset, D., Rao, J.K.M., Wlodawer, A. 1993. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli L-asparaginase, an enzyme used in cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90: 1474–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Stieglitz, K.A., Kantrowitz, E.R. 2005. Metal specificity is correlated with two crucial active site residues in Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase. Biochemistry 44: 8378–8386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]