Abstract

The interaction of cellular proteins with the gap junction protein Connexin43 (Cx43) is thought to form a dynamic scaffolding complex that functions as a platform for the assembly of signaling, structural, and cytoskeletal proteins. A high stringency Scansite search of rat Cx43 identified the motif containing Ser373 (S373) as a 14-3-3 binding site. The S373 motif and the second best mode-1 motif, containing Ser244 (S244), are conserved in rat, mouse, human, chicken, and bovine, but not in Xenopus or zebrafish Cx43. Docking studies of a mouse/rat 14-3-3θ homology model with the modeled phosphorylated S373 or S244 peptide ligands or their serine-to-alanine mutants, S373A or S244A, revealed that the pS373 motif facilitated a greater number of intermolecular contacts than the pS244 motif, thus supporting a stronger 14-3-3 binding interaction with the pS373 motif. The alanine substitution also reduced more than half the number of intermolecular contacts between 14-3-3θ and the S373 motif, emphasizing the phosphorylation dependence of this interaction. Furthermore, the ability of the wild-type or the S244A GST-Cx43 C-terminal fusion protein, but not the S373A fusion protein, to interact with either 14-3-3θ or 14-3-3ζ in GST pull-down experiments clearly demonstrated that the S373 motif mediates the direct interaction between Cx43 and 14-3-3 proteins. Blocking growth factor–induced Akt activation and presumably any Akt-mediated phosphorylation of the S373 motif in ROSE 199 cells did not prevent the down-regulation of Cx43-mediated cell–cell communication, suggesting that an Akt-mediated interaction with 14-3-3 was not involved in the disruption of Cx43 function.

Keywords: Connexin43, 14-3-3, protein–protein interactions, homology modeling, phosphorylation, mode-1 binding motif

Gap junctions are intercellular channels that facilitate the passive exchange of molecules and ions <1 kDa in size between adjacent cells. Two hemichannels in different cells, each composed of six connexin (Cx) protein subunits, dock with each other to form a contiguous gap junction channel, allowing direct communication between adjacent cells. The maintenance of tissue homeostasis and the activation and coordinated response of a large number of cells, such as in the synchronous contraction of cardiomyocytes of the heart, are dependent on gap junctional communication (GJC) (Sohl and Willecke 2004).

Mutations of several Cx genes have been implicated in some hereditary human disorders that adversely affect neurological function, hearing, vision, and the skin (Gerido and White 2004). Of the 20 murine and 21 human Cx isoforms (Sohl and Willecke 2004), Connexin43 (Cx43, the 43-kDa isoform) is the most widely expressed gap junction protein in different cell types (Willecke et al. 2002). The overexpression of Cx43 has been linked to embryonic cranial neural tube defects (Willecke et al. 2002), whereas Cx43 deficiency in mice causes a variety of heart malformations and is lethal soon after birth (Sohl and Willecke 2004).

Cx43 knockout fibroblasts proliferated faster than their wild-type counterparts, and their rates of proliferation were reduced by the exogenous expression of Cx43 in these cells (Martyn et al. 1997). In addition, suppression of tumor growth has been observed in several transformed cell lines with the restoration of GJC through the overexpression of Cx43 (Chen et al. 1995; Ruch et al. 1998; Fernstrom et al. 2002). There is also evidence that indicates that tumor suppression and the regulation of cell growth by Cx43 or its pseudogene occur independently of GJC (Olbina and Eckhart 2003; Zhang et al. 2003; Alexander et al. 2004; Kandouz et al. 2004), and this effect may be mediated by the C-terminal (CT) domain of the protein (Dang et al. 2003). The expression of Cx43 has also been found to confer resistance to cell injury, independently of gap junction channel function (Lin et al. 2003). These studies indicate that Cx43-mediated physiological effects are reliant on cell–cell communication and other mechanisms influenced by Cx43’s interactions with other cellular proteins.

Cx43-interacting proteins are thought to form a dynamic scaffolding protein complex termed the Nexus, which may function as a platform to localize signaling, structural, and cytoskeletal proteins (Duffy et al. 2002a). The yeast two-hybrid screen is commonly used to identify novel protein interactions with a bait protein of interest. The results of a yeast two-hybrid screen of a mouse embryonic cDNA library using the CT (amino acids 222–382) of Cx43 as bait identified zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), CIP85 (a novel Rab GAP-like Cx43-interacting protein), 14-3-3θ, and other potential Cx43-interacting proteins (Jin 1998; Jin and Lau 1998; Jin et al. 2004; Lan et al. 2005). The N-terminal fragment (amino acids 1–124) of 14-3-3θ that interacted with the CT of Cx43 in the two-hybrid system comprised part of the ligand-binding pocket of 14-3-3θ and contained several of the critical residues required for ligand binding (Rittinger et al. 1999).

Seven highly conserved 14-3-3 isoforms (β, γ, ɛ, η, σ, θ, ζ) that are expressed in mammalian cells play vital cellular roles through their direct interactions with other proteins involved in signal transduction, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and DNA replication (Sehnke et al. 2002). Two different phosphoserine/phosphothreonine-binding motifs that are recognized by all mammalian 14-3-3 isotypes are known as “mode-1” and “mode-2” binding motifs and consist of the consensus amino acid sequences R-X-X-pS/pT-X-P and R-X-X-X-pS/pT-X-P, respectively (Muslin et al. 1996; Yaffe et al. 1997).

In this study, we identified four potential 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motifs located on the Cx43CT tail using the Web-based prediction software Scansite. Computational modeling and molecular and biochemical analysis were applied in concert to demonstrate that only one of these four motifs, the S373 motif, could promote the interaction between Cx43 and 14-3-3 proteins. This discovery of 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motifs on the Cx43CT that facilitate an interaction between Cx43 and 14-3-3 proteins may provide valuable clues to the physiological relevance of this protein–protein interaction.

Results

Identification of 14-3-3 mode-1 sites on Cx43

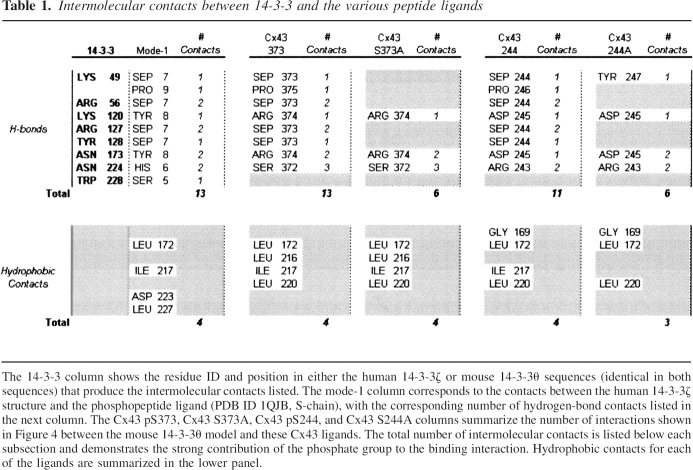

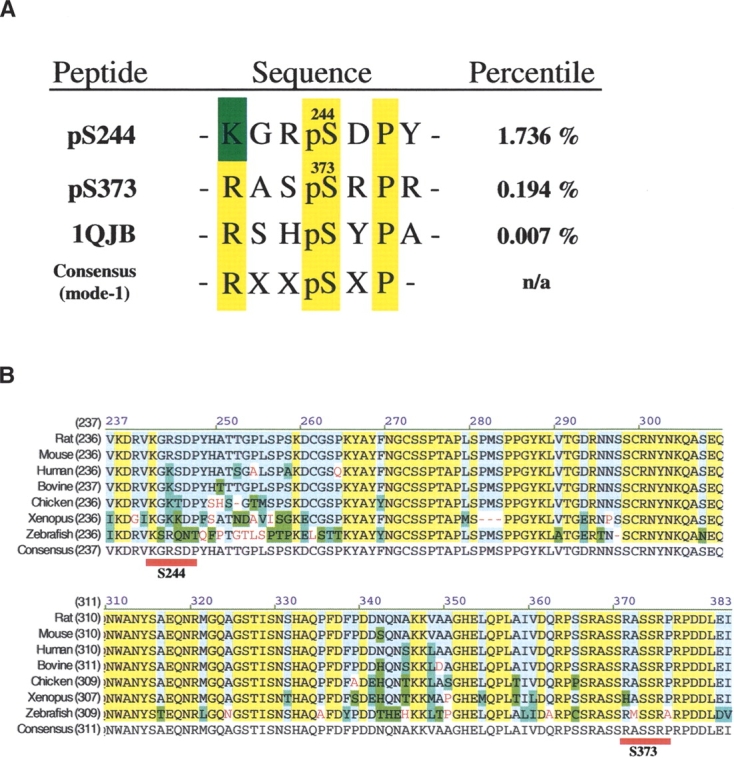

A low-stringency Scansite search for 14-3-3 mode-1 motifs on the rat Cx43 protein yielded four potential motifs directed by a threonine at position 275(T275) and by serines at positions 244(S244), 373(S373), and 369(S369), that were localized to the cytoplasmic CT region. Under high stringency, Scansite indicated the S373 site would likely serve as a physiological substrate for 14-3-3 since the S373 motif, with a score of 0.194% (Fig. 1A), fell within the top 0.2 percentile of known 14-3-3 mode-1-containing proteins in the SWISS-PROT database (SPD) (Obenauer et al. 2003). The S244 site had a distant but second best percentile score of 1.736% (Fig. 1A) as a 14-3-3 binding motif and likely represented a 14-3-3 binding motif that could not facilitate a binding interaction alone, since the percentile for this site scored well outside of the top 0.2 percentile of known 14-3-3 mode-1-containing proteins in the SPD. Interestingly, the S244 site contained a lysine at position 241 instead of an arginine at the −3 position (Fig. 1A, blue box), a conservative substitution that is found in the mode-1 binding motifs of most plant nitrate reductases (NR) and approximately one out of every eight potential mode-1 or mode-2 binding sites in Arabidopsis proteins (Sehnke et al. 2002).

Figure 1.

Alignment of potential 14-3-3 mode-1 binding motifs on Cx43. (A) A comparison of the S244 and S373 motifs on Cx43 with the mode-1 phosphopeptide (PDB ID 1JQB, S-chain) that was co-crystallized with the human 14-3-3ζ protein (PDB ID 1JQB) and with the consensus 14-3-3 mode-1 motif. Scansite percentile scores are shown for each motif. (B) Alignment of the Cx43 C-terminal tails (valine 236 through isoleucine 382) from rat, mouse, bovine, human, chicken, Xenopus, and zebrafish, highlighting the locations of the S244 and S373 mode-1 sites (underlined in red). Alignment coloring schemes were created using Vector NTI Suite 9 Align X software, where the yellow box represents identical residues, the blue box conservative/similar residues, the green box weakly similar residues, red letters nonsimilar/nonconservative residues, and the light blue box consensus residues.

The amino acid sequence alignment of the CT of Cx43 shows that the rat S373 and S244 sites (Fig. 1B, underlined in red) are conserved in the mouse, human, chicken, and bovine, but not in the Xenopus or zebrafish proteins. The S373 site is located in a region that shows strong homology, whereas the S244 site is nested in a region of Cx43 that does not show a high amount of sequence homology (Fig. 1B). Conservation of the S244 and S373 sites may suggest important and universal roles for these sites as 14-3-3 targets. In addition, a Cx43-specific function may be indicated, since 14-3-3 binding motifs are not found in other Cxs (D.J. Park, C.J. Wallick, K.D. Martyn, C. Jin, A.F. Lau, and B.J. Warn-Cramer, in prep.).

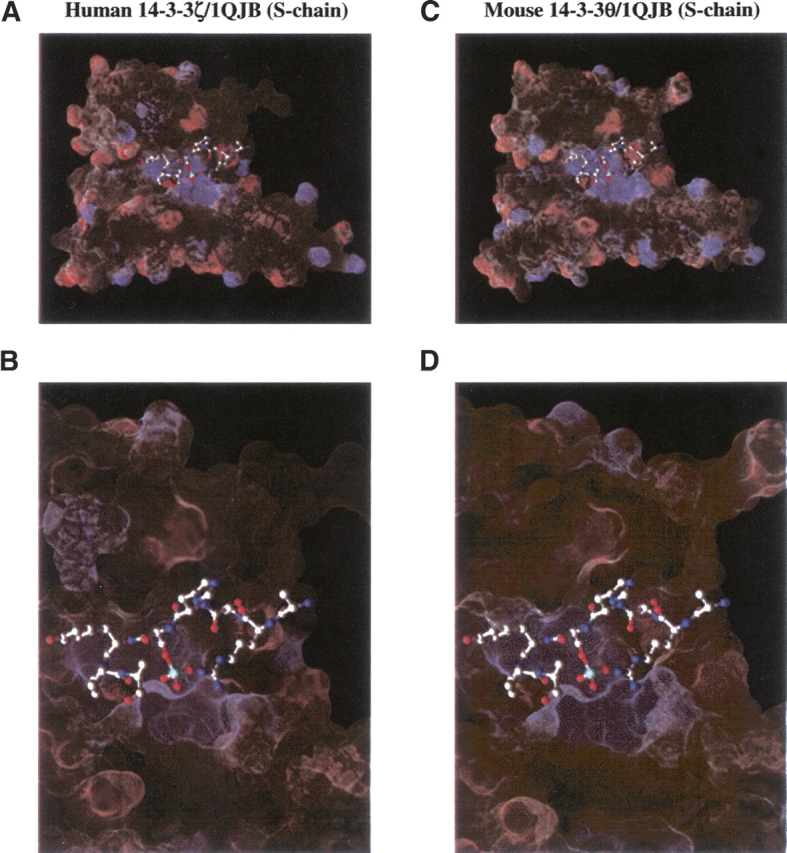

Molecular models of mouse 14-3-3θ and Cx43 mode-1 ligands

To analyze the interaction between mouse 14-3-3θ and Cx43 through molecular modeling, homology modeling of the mouse 14-3-3θ protein and the putative Cx43 ligands was performed. The crystallized structure of the human 14-3-3ζ protein bound to a mode-1 phosphopeptide (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID 1QJB) served as template to generate the homology model of the mouse 14-3-3θ protein bound to an optimum mode-1 phosphopeptide. DelPhi electrostatic surface calculations indicate a complementary positive potential surface in the binding pocket for the negative potential of the phosphoserine residue in both the human 14-3-3ζ structure (Fig. 2A,B) and the mouse 14-3-3θ models (Fig. 2C,D). At the time these studies were undertaken, the human 14-3-3ζ protein was the only crystallized 14-3-3 isoform available in the PDB; however, the human 14-3-3θ crystal structure (PDB ID 2BTP), which is 99% identical in amino acid sequence to the mouse 14-3-3θ protein, was released subsequent to the completion of our data analysis. The human and mouse 14-3-3θ proteins show a high amount of conservation, differing by a single conservative residue at position 143 that is not involved in direct peptide binding (Rittinger et al. 1999). With the subsequent release of the human 14-3-3θ crystal structure (PDB ID 2BTP), we were able to evaluate our homology-modeled mouse 14-3-3θ protein compared to the more closely related human 14-3-3θ crystal structure (PDB ID 2BTP). The backbone of the mouse 14-3-3θ model was superimposed with the human 14-3-3θ crystal structure (PDB ID 2BTP). Out of 226 residues crystallized in the human 14-3-3θ crystal structure (PDB ID 2BTP), 224 pairs of α-carbons were used to compute the root-mean-squared distance (RMSD) between the human 14-3-3θ crystal structure (PDB ID 2BTP) and the mouse 14-3-3θ model. This comparison yielded an RMSD value of 0.979 Å, verifying that a reliable mouse 14-3-3θ homology model was generated. These findings support the accuracy of the data derived from the mouse 14-3-3θ homology model and the usefulness of the in silico approach in the analysis of undetermined protein structures.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the 14-3-3θ model and the human 14-3-3ζ structure. (A) Human 14-3-3ζ bound to mode-1 phosphopeptide (PDB ID 1QJB, S-chain); (B) close-up view of bound ligand in A; (C) mouse 14-3-3θ homology model bound to a mode-1 phosphopeptide (PDB ID 1QJB, S-chain); (D) close-up view of bound ligand in C. The blue color shows the basic binding surface in the 14-3-3 binding pocket that contacts the phosphorylated phosphate group (light blue) of the S-chain ligand.

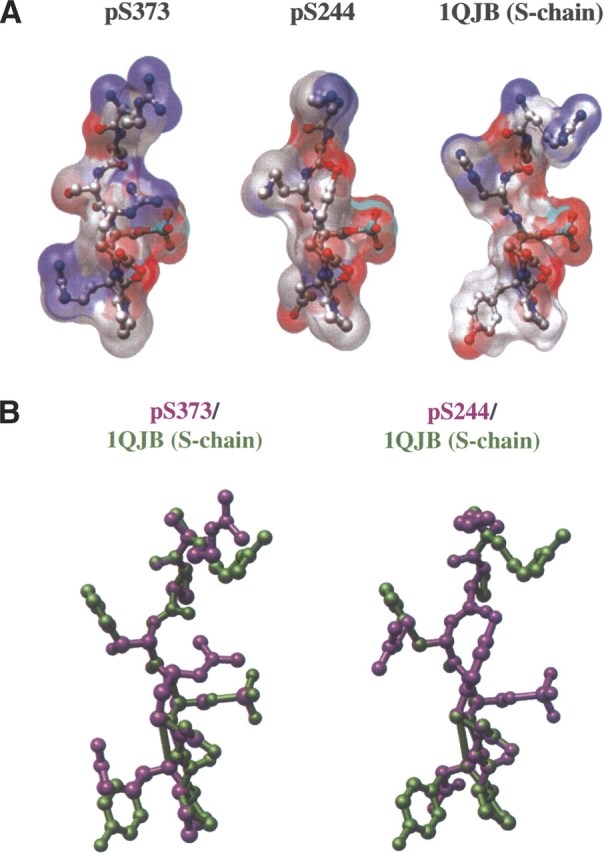

The phosphorylated S373 and S244 peptide ligands, pS373 and pS244, were modeled by site-directed mutagenesis of the cocrystallized phosphopeptide ligand (PDB ID 1QJB, S-chain) to allow the visual comparison of the phosphorylated S373 or S244 ligands with the cocrystallized phosphopeptide (PDB ID 1QJB, S-chain) by creating overlaps of the S-chain phosphopeptide (colored in green) and the phosphorylated S373 or S244 peptides (pS373, pS244; colored in purple) as shown in Figure 3. The overlaps were based on the assumption that the Cx43 phosphate groups bind and retain the same relative three-dimensional orientation and intermolecular interactions in the mouse 14-3-3θ protein as that of the phosphopeptide in the human 14-3-3ζ structure (PDB ID 1QJB). Thus, the phosphate position was held fixed from the start of the modeling process, and the remainder of the Cx43 peptides was built around that fixed position. Individual ligands were rendered in Figure 3 as ball-and-stick representations of the mode-1 phosphopeptides pS373, pS244, and 1QJB S-chain with their associated molecular surfaces, colored according to the chemical nature of the atoms (dark blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; gray, carbon; sky blue, phosphorus). The pS373 and pS244 ligands and the 1QJB S-chain show distinct surface topographical features (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, a comparison of the pS373 or pS244 peptides with the 1QJB S-chain phosphopeptide by overlay shows side-chain variability between the pS373 or pS244 peptides and the optimum 1QJB S-chain mode-1 phosphopeptide. The observable differences in surface topography and side chains for these mode-1 phosphopeptides predict unique 14-3-3 binding properties for each ligand.

Figure 3.

Ball-and-stick representation of 14-3-3 ligands. (A) Cx43 pS373 (left), Cx43 pS244 (center), and mode-1 phosphopeptide (right) fragments showing their molecular surfaces, colored according to the chemical nature of the atoms: (dark blue) nitrogen; (red) oxygen; (gray) carbon; (sky blue) phosphorus. (B) Overlays of the mode-1 phosphopeptide (1QJB, S-chain, green) with the modeled Cx43 pS373 (purple) or Cx43 pS244 (purple) phosphopeptide ligands. Partially transparent molecular surfaces distinguish differences between the Cx43 ligands and the 1QJB, S-chain by showing either a purple or green color, respectively.

Intermolecular contacts between mouse 14-3-3θ and Cx43 mode-1 ligands

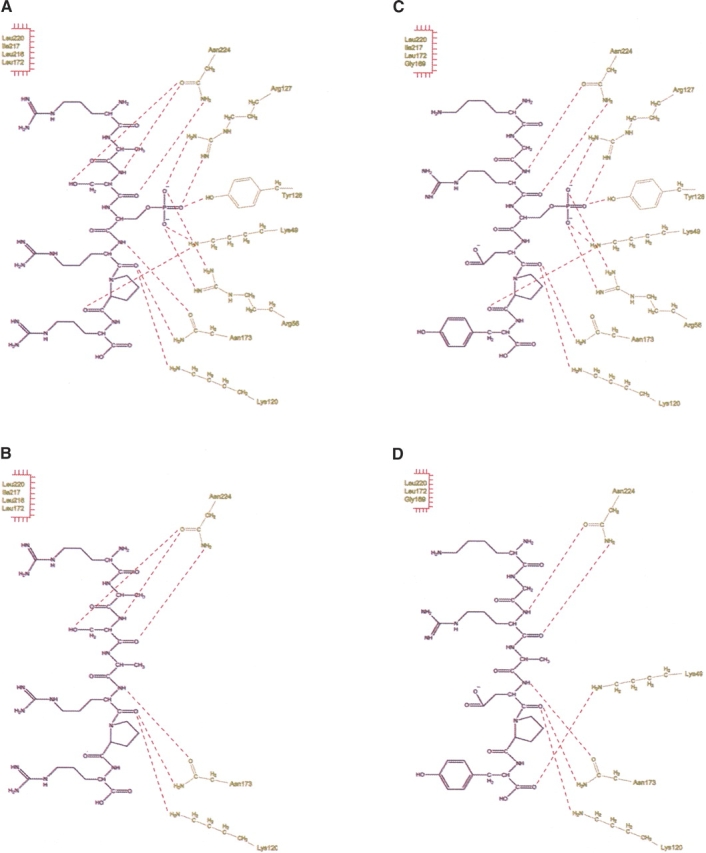

The resulting intermolecular contacts between the pS373 or pS244 peptides (Fig. 4A,C) or their respective serine-to-alanine mutants, S373A or S244A (Fig. 4B,D), and the molecular model of mouse 14-3-3θ were determined by HBPLUS (McDonald and Thornton 1994) and are summarized in Table 1. In addition to the complementary electrostatic surface potentials, seven (pS373) and five (pS244) additional H-bonds are formed between the mouse 14-3-3θ structure and their phosphoserine ligands, as opposed to their respective serine-to-alanine mutants, emphasizing the importance of the additional phosphate residues in stabilizing the 14-3-3 and Cx43 interactions (Fig. 4; Table 1). Hydrophobic contacts in the mouse 14-3-3θ/pS373 and mouse 14-3-3θ/pS244 models also shared similar intermolecular contacts to those in the human 14-3-3ζ/mode-1 phosphopeptide structure (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Intermolecular contacts between 14-3-3 and various peptide ligands. An illustration of the contacts of the mouse 14-3-3θ model with the pS373 (A), S373A (B), pS244 (C), and S244A (D) Cx43 peptide ligands. 14-3-3 contacts are gold and ligands are black. Dotted red lines highlight the H-bond contacts. Hydrophobic contacts are listed at the top left in each panel.

Table 1.

Intermolecular contacts between 14-3-3 and the various peptide ligands

Serine 373 mediates the interaction between Cx43 and the 14-3-3θ or 14-3-3ζ isoforms

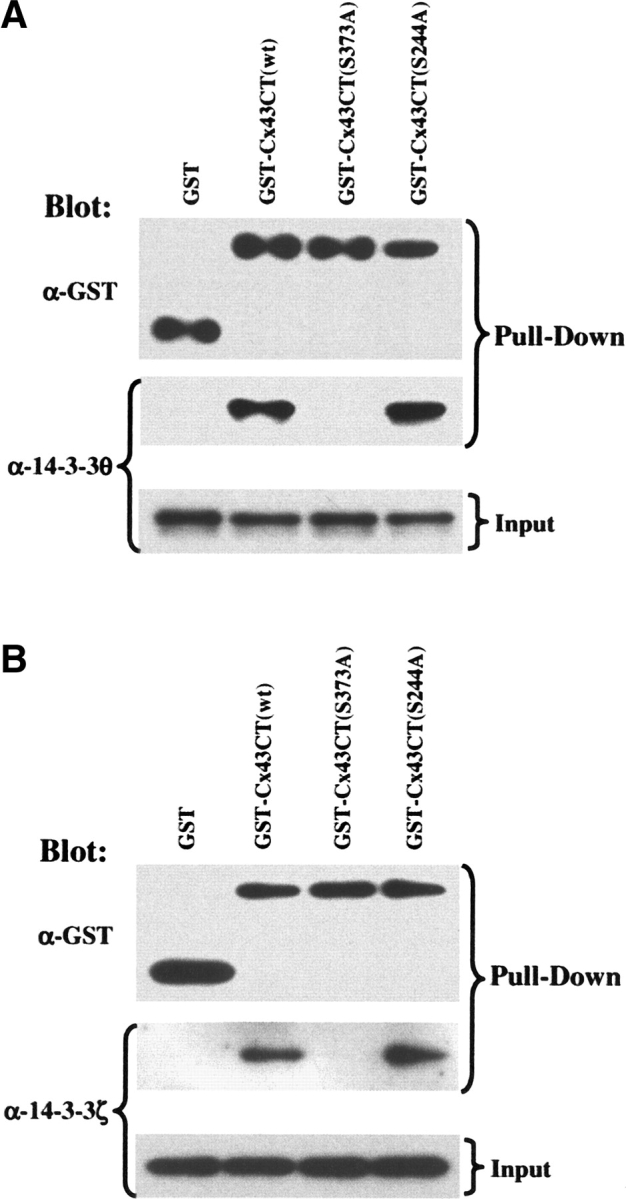

To confirm our computational and model predictions, we performed glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down experiments to test whether the interaction between 14-3-3θ and Cx43 is direct and primarily mediated by the S373 and not the S244 motif of Cx43. Figure 5A shows that both the wild-type (wt) and the S244A mutant GST-Cx43CT fusion proteins (Cx43CT, amino acids 236–382) bound to and precipitated N-terminally His6X-tagged 14-3-3θ, whereas the S373A mutant and GST alone did not interact. These results indicate that 14-3-3θ does not bind in a nonspecific manner to GST, that the S244 motif is not required for the interaction and is also not sufficient to support the interaction, and most importantly, that the S373 motif is essential for the interaction between 14-3-3θ and Cx43. Identical results were obtained if His6X-tagged 14-3-3θ was substituted with His6X-tagged 14-3-3ζ in the GST pull-down experiments (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the mode-1 motif serving as a generic binding motif for all 14-3-3 isoforms (Yaffe et al. 1997), the S373 binding motif on Cx43 bound to more than one 14-3-3 isoform.

Figure 5.

GST-Cx43CT pull-downs of 14-3-3θ and 14-3-3ζ. Western blots showing equivalent amounts of GST, Cx43CT fusion proteins (wt, S373A, S224A) and His6x-tagged 14-3-3θ (A) or 14-3-3ζ (B) proteins that were allowed to bind in a GST pull-down assay and the relative amounts of associated 14-3-3θ (A) or 14-3-3ζ (B) protein that were retained by each GST fusion protein in the pull-down (“Pull-Down”). The amount of 14-3-3 protein added to the binding reactions was equivalent as shown in the “Input” panel. Data represent five independent experiments.

Blocking Akt activation does not block growth factor–induced down-regulation of Cx43-mediated GJC

Akt kinase often phosphorylates 14-3-3 binding motifs on proteins, thereby regulating their phosphorylation-dependent association with 14-3-3 (Cahill et al. 2001; Masters et al. 2002; Basu et al. 2003; Fujita et al. 2003; Kovacina et al. 2003; Obsilova et al. 2005). We have shown that S373 on Cx43 is phosphorylated by Akt in vitro, consistent with a low-stringency Scansite search that determined that the S373 on Cx43 is a target for Akt phosphorylation (D.J. Park, C.J. Wallick, K.D. Martyn, C. Jin, A.F. Lau, and B.J. Warn-Cramer, in prep.). It seemed likely that Akt activity may be required for 14-3-3’s association with Cx43. Therefore we examined the functional effects of Akt activation on Cx43-mediated GJC in a rat ovarian surface epithelial cell line (ROSE 199 cells) by blocking lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-induced activation of PI3K, an upstream activator of Akt. ROSE 199 cells were treated with LPA for 15 min to induce the disruption of GJC, with or without a pre-treatment with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 to block the downstream activation of Akt.

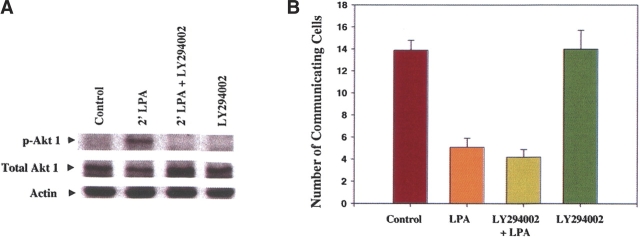

Akt-1 was activated in the ROSE 199 cells treated with LPA as shown by the detection of phosphorylated S473 on Akt-1 at 2 min after the exposure to LPA (Fig. 6A). Pre-treatment with the LY294002 inhibitor blocked LPA-dependent Akt-1 activation (Fig. 6A), but had no effect on the LPA-mediated disruption of GJC or on the baseline level of communication in cells treated with the LY294002 inhibitor alone (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that Akt-mediated phosphorylation of S373 on Cx43 was not required for Cx43 function and that an Akt-mediated association of Cx43 with 14-3-3 was not required for the growth factor–induced disruption of GJC.

Figure 6.

LY294002 blocks LPA-induced activation of Akt 1 in ROSE 199 cells but does not block the down-regulation of GJC. (A) A Western blot showing the activation of Akt 1 by LPA, but not in cells pre-treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. (B) A pre-treatment with LY294002 did not prevent the LPA induced fall in GJC and did not alter the baseline level of GJC. Cells were treated with LPA (10 μM) for 15 min prior to injection with or without a pre-treatment with LY294002 (25 μM) for 15 min. Single cells were microinjected with Lucifer Yellow dye, and the number of neighboring cells that became fluorescent because of dye transfer through gap junctions was counted after 1 min. The number of communicating cells represents the average number of neighboring cells per injection ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) from multiple cells injected on different plates on two or more days.

Discussion

Our studies supported Cx43 as a new 14-3-3 mode-1-interacting protein using both in silico and biochemical methodologies. A Scansite search for 14-3-3 mode-1 motifs on rat Cx43 identified four potential sites with the S373 motif being identified as the top 14-3-3 binding site on the CT domain of Cx43. The biochemical data concurred with the Scansite search and showed that the S373 motif, but not the S244 motif, was required for the direct interaction of Cx43CT with 14-3-3θ or with 14-3-3ζ as demonstrated by GST pull-down studies (Fig. 5A, B). In fact, a comparison of the pS373 and the pS244 sites by molecular modeling demonstrated that the pS244 site formed less intermolecular contacts with 14-3-3θ than the pS373 site (Fig. 4A,C; Table 1), which may help explain why the S244 site alone, in the GST-Cx43CT (S373A) mutant, was unable to facilitate the Cx43 and 14-3-3 interaction. Studies with a 14-3-3 phosphoserine motif antibody also indicated that both the S373A and S244A fusion proteins, but not GST alone, contained 14-3-3 binding motifs phosphorylated on serine, supporting their potential for interaction with 14-3-3. However, the importance of the S244 site cannot be entirely discounted since many proteins contain multiple 14-3-3 sites with one site, such as the S373 site, functioning as a “gatekeeper” and facilitating the interaction between the two proteins, and a second weaker binding site (i.e., S244) mediating the biological activity of the protein through a global conformational change of the protein imposed by the rigidity of the 14-3-3 protein dimer (Yaffe 2002). Binding to the second weaker site is facilitated by proximity-induced binding at the primary site.

Conformational changes in the structure of the CT domain and the second half of the cytoplasmic loop of Cx43 are important in mediating the levels of GJC and have been associated with the pH-induced closure of Cx43 channels (Duffy et al. 2002b). Furthermore, the SH3-mediated binding of Src, a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates Cx43 and down-regulates gap junctional communication (Lau 2005), to the CT domain of Cx43, has been shown in NMR studies to cause major structural changes in the CT region that disrupt the interaction of Cx43 with ZO-1 (Sorgen et al. 2004). Therefore, binding of 14-3-3 to multiple sites on the Cx43 CT would likely cause conformational changes that could influence either the interaction of Cx43 with other proteins and/or the regulation of GJC between cells. Thus, our studies cannot rule out a possible 14-3-3 interaction with the S244 site when 14-3-3 is engaged with the S373 site of Cx43 and the possibility of significant structural changes to the Cx43 CT.

14-3-3 binding to a mode-1 motif is phosphorylation-dependent, and Cx43 is a known substrate for several protein kinases (Lampe and Lau 2004; Warn-Cramer and Lau 2004). Calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II, PKG, PKC, and PKA have been predicted to phosphorylate the S373 site of Cx43 and PKC and PKG the S244 site (Hossain and Boynton 2000). Therefore, any one of these kinases could potentially facilitate an in vivo interaction between Cx43 and 14-3-3. PKC has also been shown to phosphorylate S372 adjacent to the S373 site (Saez et al. 1997). Phosphorylation of this residue may be of particular importance in the regulation of the Cx43 and 14-3-3 interaction since a previous study showed that dual phosphorylated mode-1 peptides are unable to bind 14-3-3 proteins (Muslin et al. 1996). We also modeled the 14-3-3 interaction with the S373 ligand, dually phosphorylated on the serine 372 and 373 residues, and observed that the phosphate group on serine 372 could not be spatially accommodated within the 14-3-3 ligand binding cleft when pS373 was bound (data not shown). These factors taken together with the high conservation of the S373 site (Fig. 1B) imply that the PKC phosphorylation of serine 372 may play an important physiological role in modulating the Cx43 and 14-3-3 interaction.

A Scansite search for kinases that phosphorylate the S373 and S244 sites did not list the aforementioned kinases, but predicted Clk2 (high stringency), GSK3, and Akt (low stringency) as additional phosphorylating kinases of the S373 site. Scansite did not reveal additional phosphorylating kinases for the S244 site. Clk2 belongs to the family of LAMMER kinases that phosphorylate and regulate the activity of the serine/arginine-rich (SR) protein class of pre-mRNA splicing components (Nikolakaki et al. 2002) and therefore seems unlikely to phosphorylate the S373 site on Cx43. The optimal consensus sequence for GSK phosphorylation is Ser/Thr-X-X-X-pSer/pThr (where X is any amino acid and pSer and pThr are phosphoserine and phosphothreonine, respectively) (Fiol et al. 1987). Phosphorylation of the S373 site by GSK is also unlikely since a priming phosphate, often required at the +4 position for GSK3 substrates (Jope and Johnson 2004), is lacking for the S373 site.

In many instances, it has been shown that the Akt kinase phosphorylates 14-3-3 motif-containing proteins such as the BAD, DAF-16 homologs, FoxO transcription factors, p27Kip1, PRAS40, tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), and Yes-associated protein (YAP) proteins, and promotes their interaction with 14-3-3 (Cahill et al. 2001; Masters et al. 2002; Basu et al. 2003; Fujita et al. 2003; Kovacina et al. 2003; Obsilova et al. 2005). Similarly, we have shown that the S373 site on Cx43 is an Akt phosphorylation target, both in vitro and in vivo, that could serve to promote an interaction with 14-3-3 (D.J. Park, C.J. Wallick, K.D. Martyn, C. Jin, A.F. Lau, and B.J. Warn-Cramer, in prep.). However, blocking LPA-induced Akt-1 activation in ROSE 199 cells (Fig. 6A) did not prevent the disruption of Cx43-mediated GJC (Fig. 6B), suggesting that Akt-mediated phosphorylation of the S373 site on Cx43 and a possible interaction with 14-3-3 may not play a role in regulating GJC. This result agrees with several previously described Cx43-interacting proteins that also do not seem to have a direct effect on the levels of GJC (Giepmans 2004).

Export from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is required for the multisubunit assembly of Cx43 into hexamers (Musil and Goodenough 1993). Cx43 and Cx32 constructs containing C-terminal di-lysine based ER sequences were not transported to the plasma membrane and were retained in the ER. However, Cx43 was maintained in the ER as apparent monomers unlike Cx32, which was maintained in the ER as stable hexamers, suggesting that Cx43 has a specific oligomerization and quality control mechanism that differs from other connexins (Sarma et al. 2002). The transport and assembly of Cx43 could also be subject to masking strategies described for other multimeric channel proteins that require 14-3-3 binding to overcome COPI retention in the ER to allow forward transport of only correctly oligomerized channels from the ERGIC compartment to the plasma membrane (O'Kelly et al. 2002; Nufer and Hauri 2003; Yuan et al. 2003). Cx43 is the only known Cx isoform to contain a 14-3-3 motif (D.J. Park, C.J. Wallick, K.D. Martyn, C. Jin, A.F. Lau, and B.J. Warn-Cramer, in prep.), and it is quite possible that Akt phosphorylation of the S373 motif is involved in aspects of Cx43 processing that are related to the regulation of forward transport from the ERGIC to the plasma membrane or oligomeric assembly that is unique to only the 43-kDa Cx isoform. It has been demonstrated that the trafficking of the KCNK3 potassium channel to the plasma membrane was abolished when the 14-3-3 motif was mutated to disrupt 14-3-3 binding (O'Kelly et al. 2002). Therefore, the expression of the S373A Cx43 mutant would be predicted to accumulate in the ERGIC compartment and not be transported to the plasma membrane, if Cx43 is subject to the same mechanisms observed in the forward transport of the KCNK3 channel. Taken together, the phosphorylation of the S373 motif on Cx43 by Akt or other kinases and the phosphorylation of S372 by PKC may play important roles in the mechanisms that allow forward transport and correct assembly of Cx43 from the ERGIC compartment. It should be noted that a Cx43 mutant truncated at amino acid 257 (M257) did go to the plasma membrane and form functional gap junctions (Dunham et al. 1992), as might be expected since the truncation at M257 deleted the 14-3-3 binding motifs that would normally regulate a COPI retention mechanism.

This study has combined the use of in silico predictions, molecular modeling, and biochemical approaches to identify and characterize phosphorylation-dependent 14-3-3 binding motifs on Cx43. Additional studies will be required to gain further insights into the biological functions of the Cx43 and 14-3-3 interaction in development and in different tissues and to determine whether cellular proliferation, Cx43–protein interactions, Cx43 trafficking, Cx43 oligomerization, Cx43 localization, or Cx43 turnover is altered in cells that express the S373A, S244A, or S373A/S244A Cx43 mutants. The conservation of the S373 and S244 binding motifs on Cx43 and the evidence of a direct interaction of the S373 site with 14-3-3 suggest an important role for the interaction in Cx43 regulation and encourage further study of the stoichiometry and biological functions of the Cx43 and 14-3-3 interaction.

Materials and methods

Molecular modeling of mouse 14-3-3θ

The mouse/rat 14-3-3θ model was created in Modeller 7v7 (Sali and Blundell 1993) using its sequence (NCBI accession no. P68255) as target and the structure of the human 14-3-3ζ mode-1 phosphopeptide complex (PDB ID 1QJB) as template. Specifically, residues 1–232 (of 245) of the mouse/rat 14-3-3θ sequence were modeled against chain B of the 1QJB structure file, as the peptide backbone of this chain is continuous and free of chain breaks. The required Modeller input files were then manually prepared using the alignment generated from CLUSTALX (Thompson et al. 1997). Since the mouse and rat 14-3-3θ proteins exhibit 100% identity in their protein sequences and the rat Cx43 and mouse 14-3-3θ interaction was identified in the yeast two-hybrid screen, the 14-3-3θ model is referred to as mouse 14-3-3θ throughout this paper for consistency, although rat or mouse 14-3-3θ could be used interchangeably.

Briefly, Modeller calculates distance and angle restraints on the target mouse 14-3-3θ model based on the human 14-3-3ζ template by using the results obtained from the analysis of a database of structurally homologous proteins. An objective function was generated based on these empirical spatial restraints and their CHARMM energy terms. The objective function was then optimized using the variable target function method (VTFM) (Braun and Go 1985) incorporating methods of conjugated gradients (CG) and molecular dynamics (MD) with simulated annealing (SA), resulting in the 14-3-3θ models. Additional models were created in the presence of the Cx43 ligands and, of the 20 models generated, the lowest-energy model (including the ligand) was selected for further processing. Hydrogens were added to these models using the software Reduce (Word et al. 1999). The quality of the produced models was evaluated both prior to and after the addition of hydrogens, as described below.

Molecular modeling of the Cx43 ligands

Modeling of the Cx43 ligands was also carried out in Modeller by in silico site-directed mutagenesis of the mode-1 ligand (PDB ID 1QJB), maintaining the 3D positioning of the phosphoserine residues as in the mode-1 ligand. The two segments of Cx43 that were modeled as ligands were labeled according to the position of the phosphorylated serine. The primary motif, Cx43-S373, and the secondary motif, Cx43-S244, were based on the peptide fragments RASpSRPR and KGRpSDPY, respectively. The serine-to-alanine mutants were also generated, resulting in Cx43-S373A and Cx43-S244A peptide fragments RASARPR and KGRADPY, respectively.

Electrostatic surface potential of 14-3-3θ and Cx43 molecular contacts

Intermolecular hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts for the Cx43 ligand/14-3-3θ complex were calculated in HBPLUS (McDonald and Thornton 1994), plotted in LigPlot (Wallace et al. 1995), and illustrated in CS ChemDraw Ultra v6 prior to import into Adobe Illustrator for publication-quality images. The interactive molecular graphics program Chimera 1.2199 (Pettersen et al. 2004) was used to coordinate and analyze the surface and electrostatic potentials as well as for the publication-quality figures. The solvent-excluded molecular surfaces of both the human 14-3-3ζ structure and the mouse 14-3-3θ model were calculated with the MSMS program (Sanner et al. 1996) and colored according to the electrostatic potential at those surfaces as computed by DelPhi (Rocchia et al. 2001), a program that solves the finite-difference Poisson-Boltzmann equation. The quality of the models produced was evaluated for fold (ProSa2003; ProCeryon Biosciences, AT) and stereochemistry (ProCheck; European Bioinformatics Institute). Evaluation of the models by these programs indicated that reasonable models were generated. Z-scores, an indicator of model quality, are a function of sequence length, pair interactions, surface energy, and combined surface and energy terms; they were used to assess the fold quality and to compare the modeled mouse 14-3-3θ to the crystal structure of human 14-3-3θ (PDB ID 2BTP).

Cx43 full-length and C-terminal (CT) constructs

Wild-type (wt) rat Cx43, cloned into the EcoRI site of the Bluescript SK+ vector (Stratagene), was used as template in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to perform site-directed mutagenesis to generate Cx43 mutants that substituted an alanine for a serine at residue 373 or 244. The following oligonucleotide PCR primer pairs were used to alter serine residues on Cx43 to alanine (underlined codon) on Cx43 and to add the BamHI and SalI restriction sites: at position 373, 5′-gcagcccgcgccagcgccaggcctcggc-3′ and 5′-gccgaggcctggcgctggcgtggcgcggctgc-3′; and at position 244, 5′-gtgaagggaagagccgatccttaccac-3′ and 5′-gtggtaaggatcggctcttcccttcac-3′. Cx43 inserts were isolated by BamHI and SalI restriction digests from transformed bacterial clones with DNA that sequenced with the desired mutations. The inserts were then cloned into the BamHI and SalI restriction sites of the Bluescript SK− vector.

N-terminal GST constructs of the CT tail of Cx43 (amino acids V236–I382) encoding either wild-type or S373A or S244A mutations were generated by PCR as previously described (Loo et al. 1995) using the full-length wild-type, S373A, or S244A Cx43 constructs as template. PCR primers were used to incorporate flanking BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites onto nucleotides 907 through 1356 of rat Cx43 for cloning into the pGEX-KG bacterial expression vector.

Expression and purification of GST and GST-Cx43CT fusion proteins

GST, GST-Cx43CT(wt), GST-Cx43CT(S373A), and GST-Cx43CT(S244A) fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21) by induction with 0.1 mM IPTG for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were lysed by brief sonication on ice in a PBS buffer (pH 7.0) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (8 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, 100 μg/mL aprotinin, 500 μg/mL benzamidine-HCl, 500 μg/mL EDTA, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF, 100 μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 50 μg/mL sodium orthovanadate) and clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 100,000g. GST proteins in the supernatant were purified on glutathione-agarose beads using MicroSpin Purification Modules (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified proteins were buffer exchanged and concentrated with the PBS buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 μg/mL aprotinin, 500 μg/mL benzamidine-HCl, 500 μg/mL EDTA, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF, 100 μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 mM sodium fluoride, and 50 μg/mL sodium orthovanadate; aliquoted; and stored at −80°C.

His6X-tagged 14-3-3θ and 14-3-3ζ constructs

A 5′ BamHI and 3′ EcoRI restriction site was incorporated by PCR onto the ends of 14-3-3θ and 14-3-3ζ cDNAs for cloning into the bacterial expression vector pTrcHis (Invitrogen). Fidelity of the PCR products was confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Center for Genomic, Proteomic, and Bioinformatic Research Initiative at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Protein expression and purification of His6X-tagged 14-3-3θ and 14-3-3ζ proteins

His6X-tagged 14-3-3θ and 14-3-3ζ proteins were expressed in E. coli (BL21) by induction with 0.1 mM IPTG for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were lysed by brief sonication on ice with PBS buffer (pH 8.0) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 100 μg/mL aprotinin, 500 μg/mL benzamidine-HCl, 500 μg/mL EDTA, 50 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin, 1 mM PMSF, 100 μg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 50 μg/mL sodium orthovanadate) and clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 100,000g. His-tagged proteins in the supernatants were purified using Ni-NTA Spin Columns (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified proteins were buffer exchanged and concentrated with a PBS buffer (pH 7.0) containing the same concentrations of protease and phosphatase inhibitors described above, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

GST pull-down assay and immunoblot

Ten micrograms of the GST, GST-Cx43CT(wt), GST-Cx43CT(S373A), or GST-Cx43CT(S244A) proteins was mixed with 10 μg of the His6X-tagged 14-3-3θ or 14-3-3ζ proteins in 500 μL of binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40 [v/v], 20% glycerol[v/v], 1 mM PMSF). After vortexing, 20 μL of each sample was removed and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE to verify that equal amounts of 14-3-3 proteins were present in each binding reaction. To the remaining binding reaction, 10 μL of glutathione-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added and then incubated for 3 h at 4°C with end-over-end mixing. The bound fusion proteins were pelleted by a 16,100g spin in a microfuge for 1 min at 4°C and washed six times with 500 μL of binding buffer. Proteins were eluted by the addition of 100 μL of 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. Eluted samples were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) for Western blotting. Membranes were immunoblotted with antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-GST (sc-138) antibodies were used to detect GST and the GST-Cx43CT fusion proteins. Membranes were stripped, blocked, and probed with antibodies specific for 14-3-3θ (sc-732) or 14-3-3ζ (sc-1019) proteins. Proteins were visualized on X-Omat AR film (Sigma) using an ECL detection system (Amersham).

Cell culture and treatments

ROSE 199 cells were kindly provided by Nelly Auersperg (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) and were grown in a 50:50 mixture of Media 199:MCDB 105 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Summit Biotechnology), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and gentamicin, 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin (GIBCO or Sigma), and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Two- to three-day-old nearly confluent monolayers were switched to growth media containing 0.5% FCS 16–24 h prior to treatment with 10 μM LPA (Sigma). Some cells were left untreated or were treated with LPA for 2 min and/or pre-treated for 15 min with 25 μM LY294002. After treatment, the cells were rinsed with cold PBS containing phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM NaF; 160 μM Na3VO4) and stored at −80°C.

Akt immunoblot

Whole cell lysates were prepared by the direct addition of 500 μL of hot SDS sample buffer to each 100-mm tissue culture plate that was scraped and collected in a microfuge tube then heated at 95°C for 10 min and centrifuged. Equal amounts of protein (∼20 μg) from whole cell lysates were resolved on 10% acrylamide SDS-PAGE minigels (Bio-Rad) and electrotransferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). The activation of Akt-1 was detected with rabbit antibodies specific for the active form of Akt that is phosphorylated on S473 (Cell Signaling). Membranes were stripped and probed with antibodies against Akt (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or actin (Sigma) to demonstrate equal loading. Proteins were visualized on X-Omat AR film (Sigma) using an ECL detection system (Amersham).

Measurement of GJC

An Eppendorf Micromanipulator and Transjector 5246 and Zeiss phase-contrast and epifluorescence inverted microscope was used to microinject single cells in newly confluent monolayers with a glass micropipette (Eppendorf) containing Lucifer Yellow dye (10% [w/v]). The number of neighboring cells that became fluorescent because of dye transfer was counted at ∼1 min after dye injection. Growth media was switched to 0.5% FCS overnight prior to measuring GJC. Cells were treated with or without LPA (10 μM for 15 min) with or without a pre-treatment with LY294002 (25 μM for 15 min). Each set of data represents the average number of neighboring cells per injection ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) from multiple cells injected on different plates on two or more days.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant P20-RR016453 (R. Shohet, P.I.; B.J.W.-C., project P.I.), a Research Corporation of the University of Hawaii (RCUH) bioinformatics grant (M. Alam, P.I.; B.J.W.-C. and D.J.P., project P.I.), and HS-BRIN grant RR16467 (B.J.W.-C. [travel and equipment award], D.J.P. [travel award], and Vector NTI Suite 9 software). Molecular graphics images were produced using the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Chimera package from the Computer Graphics Laboratory, UCSF supported by NIH grant P41 RR-01081. We thank Alan F. Lau for the opportunity to study this protein interaction; Ellen Freed and Chengshi Jin for the 14-3-3θ and 14-3-3ζ cDNA constructs; Eric Beyer for the wild-type Cx43 construct; Paul Q. Patek for use of and access to Silicon Graphics workstations at the University of Hawaii's Department of Microbiology; Tak Sugimura for facilitating access to the Maui High Performance Computing Center; Kendra D. Martyn and Andre S. Bachmann for critical review of the manuscript; and Anne Hernandez and Ken Takeuchi for technical assistance during the course of this study.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Bonnie J. Warn-Cramer, Natural Products and Cancer Biology Program, Cancer Research Center of Hawaii, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 651 Ilalo Street, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA; e-mail: bonnie@crch.hawaii.edu; fax: (808)-587-0742.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062172506.

References

- Alexander, D.B., Ichikawa, H., Bechberger, J.F., Valiunas, V., Ohki, M., Naus, C.C., Kunimoto, T., Tsuda, H., Miller, W.T., Goldberg, G.S. 2004. Normal cells control the growth of neighboring transformed cells independent of gap junctional communication and SRC activity. Cancer Res. 64: 1347–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu, S., Totty, N.F., Irwin, M.S., Sudol, M., Downward, J. 2003. Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14–3–3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Cell 11: 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, W. and Go, N. 1985. Calculation of protein conformations by proton–proton distance constraints. A new efficient algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 186: 611–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, C.M., Tzivion, G., Nasrin, N., Ogg, S., Dore, J., Ruvkun, G., Alexander-Bridges, M. 2001. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling inhibits DAF-16 DNA binding and function via 14–3–3-dependent and 14–3–3-independent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 13402–13410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.C., Pelletier, D.B., Ao, P., Boynton, A.L. 1995. Connexin43 reverses the phenotype of transformed cells and alters their expression of cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell Growth Differ. 6: 681–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang, X., Doble, B.W., Kardami, E. 2003. The carboxy-tail of Connexin-43 localizes to the nucleus and inhibits cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 242: 35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, H.S., Delmar, M., Spray, D.C. 2002a. Formation of the gap junction nexus: Binding partners for connexins. J. Physiol. Paris 96: 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- .Duffy, H.S., Sorgen, P.L., Girvin, M.E., O'Donnell, P., Coombs, W., Taffet, S.M., Delmar, M., Spray, D.C. 2002b. pH-dependent intramolecular binding and structure involving Cx43 cytoplasmic domains. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 36706–36714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, B., Liu, S., Taffet, S., Trabka-Janik, E., Delmar, M., Petryshyn, R., Zheng, S., Perzova, R., Vallano, M.L. 1992. Immunolocalization and expression of functional and nonfunctional cell-to-cell channels from wild-type and mutant rat heart Connexin43 cDNA. Circ. Res. 70: 1233–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrom, M.J., Koffler, L.D., Abou-Rjaily, G., Boucher, P.D., Shewach, D.S., Ruch, R.J. 2002. Neoplastic reversal of human ovarian carcinoma cells transfected with Connexin43. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 73: 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiol, C.J., Mahrenholz, A.M., Wang, Y., Roeske, R.W., Roach, P.J. 1987. Formation of protein kinase recognition sites by covalent modification of the substrate. Molecular mechanism for the synergistic action of casein kinase II and glycogen synthase kinase 3. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 14042–14048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N., Sato, S., Tsuruo, T. 2003. Phosphorylation of p27Kip1at threonine 198 by p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinases promotes its binding to 14–3–3 and cytoplasmic localization. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 49254–49260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerido, D.A. and White, T.W. 2004. Connexin disorders of the ear, skin, and lens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1662: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giepmans, B.N. 2004. Gap junctions and connexin-interacting proteins. Cardiovasc. Res. 62: 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.Z. and Boynton, A.L. 2000. Regulation of Cx43 gap junctions: The gatekeeper and the password. Sci. STKE 2000:–PE1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jin, C. In Identification and characterization of Cx43-interacting proteins pp. 93.1998. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

- Jin, C. and Lau, A.F. In Characterization of a novel SH3-containing protein that may interact with Connexin43 pp. 230–234.1998. IOS Press, Key Largo, FL.

- Jin, C., Martyn, K.D., Kurata, W.E., Lau, A.F. 2004. Connexin43 PDZ2 binding domain mutants create functional gap junctions and are altered in phosphorylation. Cell Commun. Adhes. 11: 67–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope, R.S. and Johnson, G.V. 2004. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandouz, M., Bier, A., Carystinos, G.D., Alaoui-Jamali, M.A., Batist, G. 2004. Connexin43 pseudogene is expressed in tumor cells and inhibits growth. Oncogene 23: 4763–4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacina, K.S., Park, G.Y., Bae, S.S., Guzzetta, A.W., Schaefer, E., Birnbaum, M.J., Roth, R.A. 2003. Identification of a proline-rich Akt substrate as a 14–3–3 binding partner. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 10189–10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe, P.D. and Lau, A.F. 2004. The effects of connexin phosphorylation on gap junctional communication. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36: 1171–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z., Kurata, W.E., Martyn, K.D., Jin, C., Lau, A.F. 2005. Novel rab GAP-like protein, CIP85, interacts with Connexin43 and induces its degradation. Biochemistry 44: 2385–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sci. STKE Lau, . :A.F. 2005. c-Src: Bridging the gap between phosphorylation- and acidification-induced gap junction channel closure. 2005:–pe33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H., Yang, J., Liu, S., Takano, T., Wang, X., Gao, Q., Willecke, K., Nedergaard, M. 2003. Connexin mediates gap junction-independent resistance to cellular injury. J. Neurosci. 23: 430–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo, L.W., Berestecky, J.M., Kanemitsu, M.Y., Lau, A.F. 1995. pp60src-mediated phosphorylation of Connexin 43, a gap junction protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 12751–12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn, K.D., Kurata, W.E., Warn-Cramer, B.J., Burt, J.M., TenBroek, E., Lau, A.F. 1997. Immortalized Connexin43 knockout cell lines display a subset of biological properties associated with the transformed phenotype. Cell Growth Differ. 8: 1015–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters, S.C., Subramanian, R.R., Truong, A., Yang, H., Fujii, K., Zhang, H., Fu, H. 2002. Survival-promoting functions of 14–3–3 proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30: 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, I.K. and Thornton, J.M. 1994. Satisfying hydrogen bonding potential in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 238: 777–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil, L.S. and Goodenough, D.A. 1993. Multisubunit assembly of an integral plasma membrane channel protein, gap junction Connexin43, occurs after exit from the ER. Cell 74: 1065–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslin, A.J., Tanner, J.W., Allen, P.M., Shaw, A.S. 1996. Interaction of 14–3–3 with signaling proteins is mediated by the recognition of phosphoserine. Cell 84: 889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakaki, E., Du, C., Lai, J., Giannakouros, T., Cantley, L., Rabinow, L. 2002. Phosphorylation by LAMMER protein kinases: Determination of a consensus site, identification of in vitro substrates, and implications for substrate preferences. Biochemistry 41: 2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nufer, O. and Hauri, H.P. 2003. ER export: Call 14–3–3. Curr . Biol. 13: R391–R393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer, J.C., Cantley, L.C., Yaffe, M.B. 2003. Scansite 2.0: Proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3635–3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obsilova, V., Vecer, J., Herman, P., Pabianova, A., Sulc, M., Teisinger, J., Boura, E., Obsil, T. 2005. 14–3–3 protein interacts with nuclear localization sequence of forkhead transcription factor FoxO4. Biochemistry 44: 11608–11617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kelly, I., Butler, M.H., Zilberberg, N., Goldstein, S.A. 2002. Forward transport. 14–3–3 binding overcomes retention in endoplasmic reticulum by dibasic signals. Cell 111: 577–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbina, G. and Eckhart, W. 2003. Mutations in the second extracellular region of Connexin 43 prevent localization to the plasma membrane, but do not affect its ability to suppress cell growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 1: 690–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen, E.F., Goddard, T.D., Huang, C.C., Couch, G.S., Greenblatt, D.M., Meng, E.C., Ferrin, T.E. 2004. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25: 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittinger, K., Budman, J., Xu, J., Volinia, S., Cantley, L.C., Smerdon, S.J., Gamblin, S.J., Yaffe, M.B. 1999. Structural analysis of 14–3–3 phosphopeptide complexes identifies a dual role for the nuclear export signal of 14–3–3 in ligand binding. Mol. Cell 4: 153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchia, W., Alexov, E., Honig, B. 2001. Extending the applicability of the nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann equation: Multiple dielectric constants and multivalent ions. J. Phys. Chem. 105: 6507–6514. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, R.J., Cesen-Cummings, K., Malkinson, A.M. 1998. Role of gap junctions in lung neoplasia. Exp. Lung Res. 24: 523–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez, J.C., Nairn, A.C., Czernik, A.J., Fishman, G.I., Spray, D.C., Hertzberg, E.L. 1997. Phosphorylation of Connexin43 and the regulation of neonatal rat cardiac myocyte gap junctions. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 29: 2131–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali, A. and Blundell, T.L. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234: 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanner, M.F., Olson, A.J., Spehner, J.C. 1996. Reduced surface: An efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers 38: 305–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, J.D., Wang, F., Koval, M. 2002. Targeted gap junction protein constructs reveal connexin-specific differences in oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 20911–20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnke, P.C., DeLille, J.M., Ferl, R.J. 2002. Consummating signal transduction: The role of 14–3–3 proteins in the completion of signal-induced transitions in protein activity. Plant Cell 14:(Suppl): S339–S354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, G. and Willecke, K. 2004. Gap junctions and the connexin protein family. Cardiovasc. Res. 62: 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorgen, P.L., Duffy, H.S., Sahoo, P., Coombs, W., Delmar, M., Spray, D.C. 2004. Structural changes in the carboxyl terminus of the gap junction protein Connexin43 indicates signaling between binding domains for c-Src and zonula occludens-1. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 54695–54701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D., Gibson, T.J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., Higgins, D.G. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, A.C., Laskowski, R.A., Thornton, J.M. 1995. LIGPLOT: A program to generate schematic diagrams of protein–ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 8: 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warn-Cramer, B.J. and Lau, A.F. 2004. Regulation of gap junctions by tyrosine protein kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1662: 81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke, K., Eiberger, J., Degen, J., Eckardt, D., Romualdi, A., Guldenagel, M., Deutsch, U., Sohl, G. 2002. Structural and functional diversity of connexin genes in the mouse and human genome. Biol. Chem. 383: 725–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word, J.M., Lovell, S.C., Richardson, J.S., Richardson, D.C. 1999. Asparagine and glutamine: Using hydrogen atom contacts in the choice of side-chain amide orientation. J. Mol. Biol. 285: 1735–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, M.B. 2002. How do 14–3–3 proteins work? Gatekeeper phosphorylation and the molecular anvil hypothesis. FEBS Lett. 513: 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, M.B., Rittinger, K., Volinia, S., Caron, P.R., Aitken, A., Leffers, H., Gamblin, S.J., Smerdon, S.J., Cantley, L.C. 1997. The structural basis for 14–3–3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell 91: 961–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H., Michelsen, K., Schwappach, B. 2003. 14–3–3 dimers probe the assembly status of multimeric membrane proteins. Curr. Biol. 13: 638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.W., Kaneda, M., Morita, I. 2003. The gap junction-independent tumor-suppressing effect of Connexin 43. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 44852–44856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]