Abstract

Reduced hen lysozyme has a residual structure involving long-range interaction. It has been demonstrated that a single mutation (A9G, W62G, W111G, or W123G) in the residual structure differently modulates the long-range interactions of reduced lysozyme. To examine whether such variations in the residual structure affect amyloid formation, reduced and alkylated mutant lysozymes were incubated under the amyloid-fibrillation condition. From the analyses of CD spectra and thioflavine T fluorescences, it was suggested that variation in residual structure led to different amyloid formation. Interestingly, the extent of amyloid formation did not always correlate with the extent to which the residual structure was maintained, resulting in the involvement of a hydrophobic cluster normally contained in W111 in the reduced lysozyme.

Keywords: lysozyme, amyloid formation, residual structure

A number of human diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Creutzfeld-Jacob disease, and AL amyloidosis, originate from the misfolding of protein (Bellotti et al. 2000; Uversky 2003; Chakraborty et al. 2005; Veerhuis et al. 2005). The toxic proteins related to these diseases do not have special characteristics in terms of their three-dimensional structures or amino acid sequences, but amyloid fibrils composed of β-sheet structure are common features (Sunde et al. 1997). It has also been shown that many disease-unrelated proteins are able to form amyloid fibrils under appropriate conditions (Guijarro et al. 1998; Konno et al. 1999; Damaschun et al. 2000; Yutani et al. 2000; Pertinhez et al. 2001; Pavlov et al. 2002). Accordingly, it is proposed that amyloid formation is a generic property of all proteins (Dobson 1999). Amyloid formation has been shown to proceed from extensively or partially unfolded states (Dobson 2003; Uversky and Fink 2004; Calamai et al. 2005) and even in small polypeptide fragments of denatured conformation (Lopez de La Paz et al. 2002; Frare et al. 2004). These findings suggested that the protein conformation in the denatured state is involved in amyloid formation. Although local elements in residual structures under denaturing conditions have been identified in many proteins (Schwalbe et al. 1997; Shortle and Ackerman 2001; Lietzow et al. 2002), there are few reports for the relationship between amyloid formation and residual structures involving long-range interactions.

Hen egg-white lysozyme (HEL) was the first enzyme whose three-dimensional structure was elucidated using X-ray crystallography (Imoto et al. 1972) and it has been widely used for studying conformational stability, protein folding, and so on. HEL is composed of a primarily α-helical structure with two short β-strands and has four disulfide bonds. Recently, it has been reported that non-disulfide-bonded HEL could form amyloid fibrils (Cao et al. 2004; Niraula et al. 2004). On the other hand, six hydrophobic clusters were identified in reduced HEL under extremely denaturing conditions using NMR measurements of spin–spin relaxation time of the main chain (Schwalbe et al. 1997). We showed that W62 played an important role for the folding process (Ueda et al. 1990, 1995, 1996). Schwalbe's and our groups have demonstrated that these clusters were simultaneously disrupted by the mutation W62G, indicating the presence of long-range interactions within these hydrophobic clusters (Klein-Seetharaman et al. 2002). Therefore, we also examined the effect of the residual structure on amyloid formation using reduced W62G HEL. As a result, it was found that the disruption of the residual structure inhibited amyloid formation in HEL (Ohkuri et al. 2005).

Schwalbe's and our groups also have recently found that single-point mutations of the hydrophobic residue in the residual structure modulated the compactness and long-range interactions of reduced lysozyme, resulting in the production of mutant HELs possessing various residual structures (Wirmer et al. 2004). In this paper, we examine the amyloid formation of the wild-type and single-mutant HELs to define the relationship between amyloid formation and the residual structure involving long-range interactions in reduced and alkylated HEL.

Results and Discussion

Preparation of single-mutant HELs where residual structures are modulated

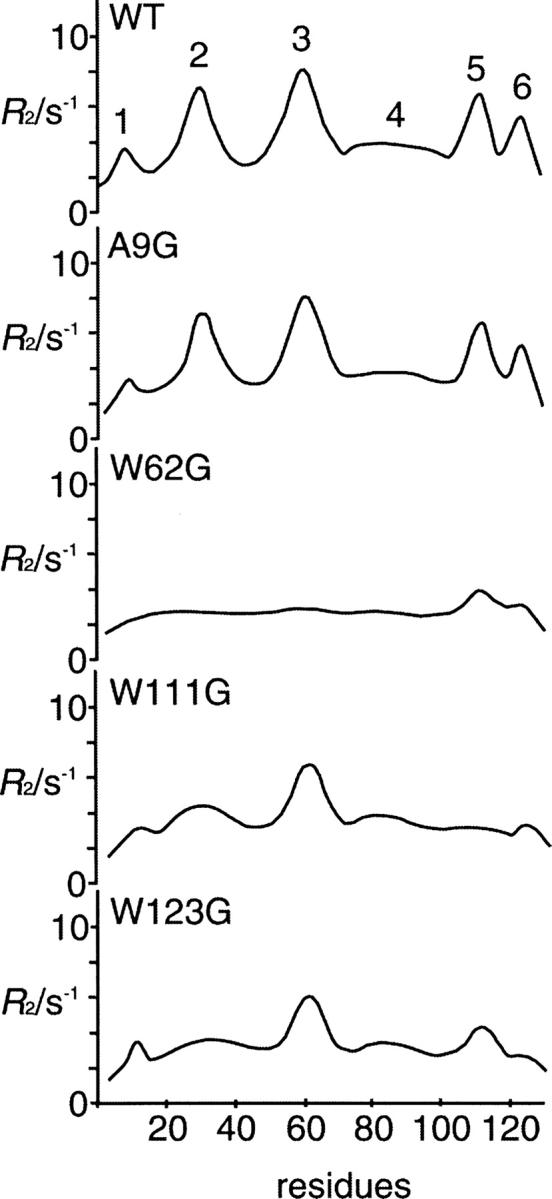

Transverse relaxation rates (R2), which are measured by 15N-1H heteronuclear NMR, show conformational exchange in the millisecond time scale (Wagner 1993). The measurement of the R2 of each residue in the denatured protein can be used as a probe for the presence of a residual structure (Schwalbe et al. 1997). Figure 1 shows the previous results of R2 values in the reduced and alkylated HELs at pH 2.0 (Wirmer et al. 2004). Six regions with elevated R2 values in the reduced wild-type HEL were found to correlate with the location of hydrophobic residues, indicating the existence of hydrophobic clusters. The result of W62G HEL (in cluster 3) indicated that all hydrophobic clusters were simultaneously disrupted. R2 values in reduced and alkylated A9G HEL (in cluster 1) were similar to those in the wild-type HEL. W111G HEL (in cluster 5) and W123G HEL (in cluster 6) showed different long-range interactions in the residual structure. We prepared these mutant HELs from the yeast Pichia pastoris according to previously described methods (Mine et al. 1999) and performed their reductions and carboxamide methylations (CAM).

Figure 1.

Transverse relaxation rates (R2) in the reduced and alkylated HELs at pH 2.0. Six clusters are detected in the wild-type lysozyme. This figure was schematically redrawn based on our former results (Wirmer et al. 2004).

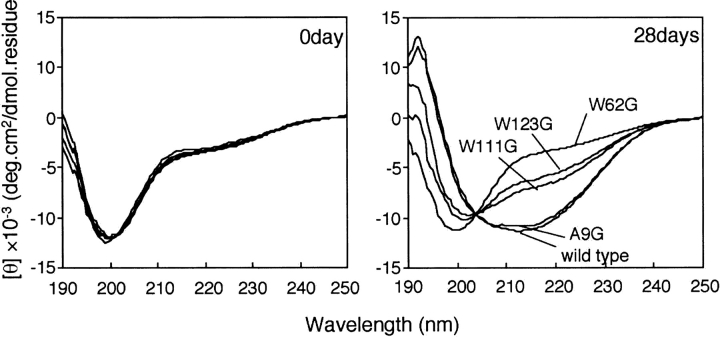

Effect of the residual structure in CAM HEL on β-structure transition at pH 2.0

The CAM wild-type HEL and CAM mutant HELs were incubated in 50 mM sodium malate at pH 2.0, in which non-disulfide-bonded HEL could form amyloid fibrils (Niraula et al. 2004). A common feature of amyloid fibrils is the formation of β-structure. Figure 2A shows the CD spectra of the CAM wild-type HEL and CAM mutant HELs acquired immediately after dissolving in the solution. All spectra showed a negative peak at ∼200 nm, which is a common CD feature of random coil structure (Cao et al. 2004). Figure 2B shows the CD spectra of CAM HELs after 28 d of incubation. The CD spectrum of the CAM wild-type HEL showed the extension of a single negative peak around 215 nm, which is a feature of β-structure, whereas the spectrum of CAM W62G HEL was almost unchanged even after 28 d of incubation. Clearly, the formation of the β-structure was induced in the CAM wild-type HEL, but not in CAM W62G HEL, by incubation in 50 mM sodium malate at pH 2.0 (Ohkuri et al. 2005). The CD spectrum of CAM A9G HEL was similar to that of the wild type. On the other hand, the maximum ellipticity of the single negative peak ∼215 nm in the CD spectra of CAM W111G HEL and CAM W123G HEL fell between those of the CAM wild-type HEL and CAM W62G HEL. The extent of negative ellipticity at 215 nm of CAM W111G HEL was slightly greater than that of CAM W123G HEL. Since the above results were obtained reproducibly, the difference in the extent of negative ellipticity at 215 nm was subtle but significant. The CD spectra of the CAM wild-type HEL and CAM mutant HELs in Figure 2B were almost unchanged after 28 d of incubation (data not shown). These results suggested that the difference in the residual structure in CAM HELs led to a different extent of β-structure formation.

Figure 2.

Time dependence of CD spectra of CAM HELs after 0 d or 28 d of incubation in 50 mM sodium malate at pH 2.0.

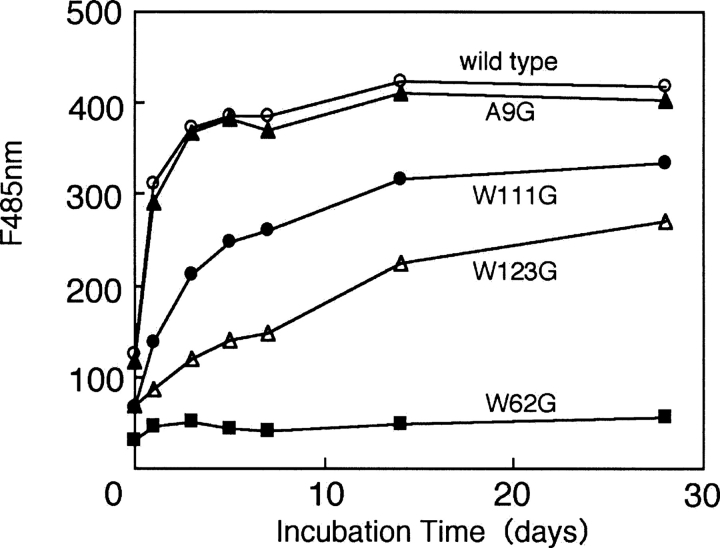

Amyloid formation of CAM mutant HELs at pH 2.0

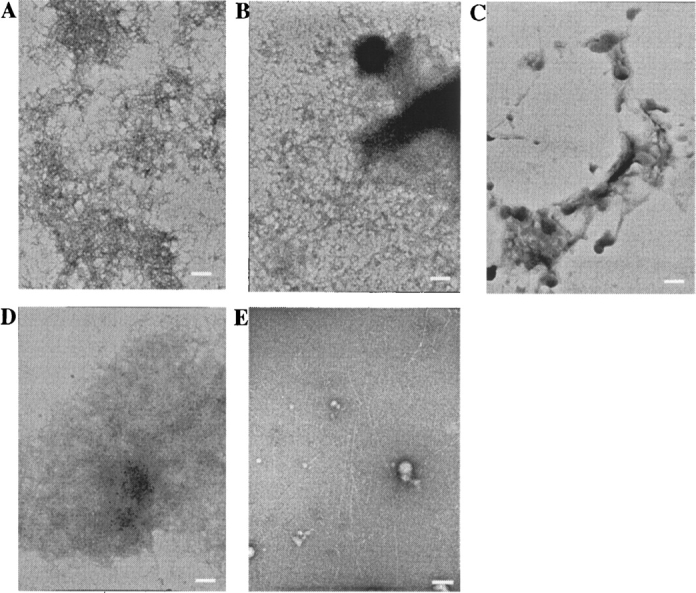

The diagnosis of amyloid formation was analyzed by thioflavine T (ThT) fluorescence (LeVine 1993). Figure 3 shows the fluorescence emission of ThT at 485 nm in the presence of the CAM wild-type HEL and CAM mutant HELs taken at intervals during the incubation at pH 2.0. The fluorescence intensity of ThT in the presence of the CAM wild-type lysozyme increased after 1 d of incubation, whereas that in the presence of CAM W62G lysozyme did not increase after 28 d of incubation, as was demonstrated in our previous results (Ohkuri et al. 2005). The transition of ThT fluorescence intensities at 485 nm of CAM A9G HEL was similar to that of the CAM wild-type HEL during the incubation at pH 2.0. On the other hand, the ThT fluorescence intensities at 485 nm of CAM W111G HEL and CAM W123G HEL were lower than that of the CAM wild-type HEL at all days of incubation. The ThT fluorescence intensities of CAM W111G HEL and CAM W123G HEL reached a plateau after 28 d of incubation, indicating that the amyloid formation of CAM W111G HEL was higher than that of CAM W123G HEL. Such ability for amyloid formation on CAM HELs is consistent with degree of the negative ellipticity at 215 nm in CAM HELs. Moreover, the formations of the fibrils after incubation of CAM HELs for 4 mo were examined by electron microscopy (EM) analyses. The EM graphs of the CAM wild-type HEL and CAM A9G HEL showed dense meshworks of fibrils (Fig. 4A,B). Although that of CAM W111G HEL showed extensive networks of fibrils with similar morphological features to the CAM wild-type HEL, that of CAM W123G HEL showed a few fibrils formation (Fig. 4D,E). Moreover, the EM graphs revealed that CAM W62G HEL did not form the fibrils (Fig. 4C). Thus, it was suggested that the extents of the fibrils formation in CAM HELs correlated with those of the fluorescence intensities of ThT in the presence of CAM HELs.

Figure 3.

The fluorescence emission at 485 nm of ThT in the presence of CAM HELs during the incubation at pH 2.0.

Figure 4.

Electron micrographs of solutions of the CAM wild-type HEL (A), CAM A9G HEL (B), CAM W62G HEL (C), CAM W111G HEL (D), and CAM W123G HEL (E) in 50 mM sodium malate at pH 2.0 after incubation at 30°C for 4 mo and a protein concentration of 8 mg/mL. The scale bars represent 250 nm.

Involvement of the residual structure with amyloid formation

In this study, we examined whether the residual structure of reduced and alkylated HEL had an effect on amyloid formation. Although it has been suggested that the simultaneous disruption of the residual structure inhibited amyloid formation of CAM HEL (Ohkuri et al. 2005), it was unknown whether partial disruption of the residual structure had an effect on amyloid formation. Here, we showed that the variation in the residual structure caused a distinct extent of amyloid formation. The extent of amyloid formation of CAM W111G HEL was higher than that of CAM W123G HEL during the incubation at pH 2.0 (Fig. 3), whereas the residual structure of CAM W111G HEL was apparently disrupted more than that of CAM W123G HEL (Fig. 1). This is the novel finding in this paper: that the extent of residual structure disruption in reduced and alkylated HEL did not always correlate with the extent of amyloid formation. The difference in the extent of residual structure disruption between these mutant HELs was observed in cluster 5. Namely, the hydrophobic cluster 5 in CAM W123G HEL was slightly maintained, whereas that of CAM W111G HEL completely disappeared. The slight existence of a hydrophobic cluster 5 in CAM W123G HEL may lead to a different long-range interaction in the residual structure, resulting in the lower amyloid formation in CAM W123G HEL than in CAM W111G HEL.

Recently, the effect of the different conformations of a partially unfolded human muscle acylphosphatase (AcP) on amyloid fibril formation has been reported (Calamai et al. 2005). The results showed that AcP was able to form amyloid fibrils with a high β-sheet content from partially unfolded states with very different secondary structure contents by variation of the solution condition. On the other hand, Jahn et al. (2006) have investigated the roles of different partially unfolded states in amyloid–fibril formation of human β-2-microglobulin. It was demonstrated that the rate of fibril elongation correlated directly with the population of intermediates. However, these studies have never focused on differences in residual structure involving long-range interaction in denatured protein. In this paper, it was first elucidated that the variation in residual structure involving long-range interactions in the denatured state influences amyloid formation. Our findings provide new insight into the mechanism of amyloid fibril formation.

Materials and methods

Preparation of mutant HELs

Site-directed mutagenesis of HEL was performed by PCR according to previously described methods (Mine et al. 1999). Mutations were confirmed using DNA sequence analysis. The mutant HELs were expressed in P. pastoris GS115 cells harboring the recombinant plasmid constructed using a pPIC9 vector (Invitrogen), as described previously (Mine et al. 1999). Purification of the mutant HELs were carried out according to the previously described method (Mine et al. 1999).

Characterization of amyloid formation

CAM HELs in 50 mM sodium malate at pH 2.0 were incubated at 30°C and a protein concentration of 8 mg/mL, according to a previously described method with slight modification (Ohkuri et al. 2005). Characterizations of amyloid aggregates of CAM HELs were carried out using a CD spectropolarimeter and fluorescence spectrometer, according to the previously described method (Ohkuri et al. 2005). After the protein solution was diluted with 10 mM HCl to a final concentration of 0.08 mg/mL, the CD spectra of the CAM HELs were obtained with a Jasco-J 720 spectropolarimeter. The ThT binding curve was obtained by adding the protein solution (10 μL) to a 25 μM solution (990 μL) of ThT in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The excitation wavelength was fixed at 440 nm and the emission was collected at 485 nm.

Electron microscopic analysis

CAM HELs in 50 mM sodium malate at pH 2.0 were incubated at 30°C and a protein concentration of 8 mg/mL for 4 mo. Each sample was negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate. The grids were then examined using a JEM-100CX electron microscope (JEOL) at 80 kV.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Takaaki Kanemaru of Kyushu University Hospital for his valuable technical assistance with both the electron microscopy and photography. We thank KN-International (USA) for improvement of our English.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Tadashi Ueda, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyushu University, 3-1-1 Maidashi, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan; e-mail: ueda@phar.kyushu-u.ac.jp; fax: +81-92-642-6667.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062258206.

Abbreviations: HEL, hen egg-white lysozyme; CAM HEL, reduced and carboxamide-methylated HEL; ThT, thioflavine T.

References

- Bellotti, V., Mangione, P., Merlini, G. 2000. Review: Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis—The archetype of structural and pathogenic variability. J. Struct. Biol. 130: 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamai, M., Chiti, F., Dobson, C.M. 2005. Amyloid fibril formation can proceed from different conformations of a partially unfolded protein. Biophys. J. 89: 4201–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, A., Hu, D., Lai, L. 2004. Formation of amyloid fibrils from fully reduced hen egg white lysozyme. Protein Sci. 13: 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, C., Nandi, S., Jana, S. 2005. Prion disease: A deadly disease for protein misfolding. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 6: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaschun, G., Damaschun, H., Fabian, H., Gast, K., Krober, R., Wieske, M., Zirwer, D. 2000. Conversion of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase into amyloid-like structure. Proteins 39: 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, C.M. 1999. Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24: 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— 2003. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature 426: 884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frare, E., Polverino De Laureto, P., Zurdo, J., Dobson, C.M., Fontana, A. 2004. A highly amyloidogenic region of hen lysozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 23: 1153–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro, J.I., Sunde, M., Jones, J.A., Campbell, I.D., Dobson, C.M. 1998. Amyloid fibril formation by an SH3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 4224–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoto, T., Johnson, L.N., North, A.C.T., Philip, D.C., Rupley, J. 1972. Vertebrate lysozyme. In The Enzymes (ed. Boyer P.D.) . pp. 665–863. 3d ed., Academic Press, New York Vol. 7:. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, T.R., Parker, M.J., Homans, S.W., Radford, S.E. 2006. Amyloid formation under physiological conditions proceeds via a native-like folding intermediate. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Seetharaman, J., Oikawa, M., Grimshaw, S.B., Wirmer, J., Duchardt, E., Ueda, T., Imoto, T., Smith, L.J., Dobson, C.M., Schwalbe, H. 2002. Long-range interactions within a nonnative protein. Science 295: 1719–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno, T., Murata, K., Nagayama, K. 1999. Amyloid-like aggregates of a plant protein: A case of a sweet-tasting protein, monellin. FEBS Lett. 454: 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine, H. 1993. Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer's disease β-amyloid peptides: Detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci. 2: 404–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lietzow, M.A., Jamin, M., Jane Dyson, H.J., Wright, P.E. 2002. Mapping long-range contacts in a highly unfolded protein. J. Mol. Biol. 322: 655–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez de La Paz, M., Goldie, K., Zurdo, J., Lacroix, E., Dobson, C.M., Hoenger, A., Serrano, L. 2002. De novo designed peptide-based amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 16052–16057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine, S., Ueda, T., Hashimoto, Y., Tanaka, Y., Imoto, T. 1999. High-level expression of uniformly 15N-labeled hen lysozyme in Pichia pastoris and identification of the site in hen lysozyme where phosphate ion binds using NMR measurements. FEBS Lett. 448: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niraula, T.N., Konno, T., Li, H., Yamada, H., Akasaka, K., Tachibana, H. 2004. Pressure-dissociable reversible assembly of intrinsically denatured lysozyme is a precursor for amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 4089–4093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuri, T., Shioi, S., Imoto, T., Ueda, T. 2005. Effect of the structure of the denatured state of lysozyme on the aggregation reaction at the early stages of folding from the reduced form. J. Mol. Biol. 347: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, N.A., Cherny, D.I., Heim, G., Jovin, T.M., Subramaniam, V. 2002. Amyloid fibrils from the mammalian protein prothymosin α. FEBS Lett. 517: 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertinhez, T.A., Bouchard, M., Tomlinson, E.J., Wain, R., Ferguson, S.J., Dobson, C.M., Smith, L.J. 2001. Amyloid fibril formation by a helical cytochrome. FEBS Lett. 495: 184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe, H., Fiebig, K.M., Buck, M., Jones, J.A., Grimshaw, S.B., Spencer, A., Glaser, S.J., Smith, L.J., Dobson, C.M. 1997. Structural and dynamical properties of a denatured protein. Heteronuclear 3D NMR experiments and theoretical simulations of lysozyme in 8 M urea. Biochemistry 36: 8977–8991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortle, D. and Ackerman, M.S. 2001. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science 293: 487–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunde, M., Serpell, L.C., Bartlam, M., Fraser, P.E., Pepys, M.B., Blake, C.C. 1997. Common core structure of amyloid fibrils by synchrotron X-ray diffraction. J. Mol. Biol. 273: 729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T., Yamada, H., Aoki, H., Imoto, T. 1990. Effect of chemical modifications of tryptophan residues on the folding of reduced hen egg-white lysozyme. J. Biochem. 108: 886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T., Abe, Y., Ohkuri, T., Kawano, K., Terada, Y., Imoto, T. 1995. Kinetically trapped structure in the renaturation of reduced oxindolealanine 62 lysozyme. Biochemistry 34: 16178–16185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T., Ohkuri, T., Imoto, T. 1996. Identification of the peptide region that folds native conformation in the early stage of the renaturation of reduced lysozyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 228: 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky, V.N. 2003. A protein-chameleon: Conformational plasticity of α-synuclein, a disordered protein involved in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 21: 211–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky, V.N. and Fink, A.L. 2004. Conformational constraints for amyloid fibrillation: The importance of being unfolded. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1698: 131–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veerhuis, R., Boshuizen, R.S., Familian, A. 2005. Amyloid associated proteins in Alzheimer's and prion disease. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 4: 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G. 1993. NMR relaxation and protein mobility. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 3: 748–754. [Google Scholar]

- Wirmer, J., Schlorb, C., Klein-Seetharaman, J., Hirano, R., Ueda, T., Imoto, T., Schwalbe, H. 2004. Modulation of compactness and long-range interactions of unfolded lysozyme by single point mutations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43: 5780–5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutani, K., Takayama, G., Goda, S., Yamagata, Y., Maki, S., Namba, K., Tsunasawa, S., Ogasahara, K. 2000. The process of amyloid-like fibril formation by methionine aminopeptidase from a hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus . Biochemistry 39: 2769–2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]