Abstract

The mammalian α/β T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire plays a pivotal role in adaptive immunity by recognizing short, processed, peptide antigens bound in the context of a highly diverse family of cell-surface major histocompatibility complexes (pMHCs). Despite the extensive TCR–MHC interaction surface, peptide-independent cross-reactivity of native TCRs is generally avoided through cell-mediated selection of molecules with low inherent affinity for MHC. Here we show that, contrary to expectations, the germ line-encoded complementarity determining regions (CDRs) of human TCRs, namely the CDR2s, which appear to contact only the MHC surface and not the bound peptide, can be engineered to yield soluble low nanomolar affinity ligands that retain a surprisingly high degree of specificity for the cognate pMHC target. Structural investigation of one such CDR2 mutant implicates shape complementarity of the mutant CDR2 contact interfaces as being a key determinant of the increased affinity. Our results suggest that manipulation of germ line CDR2 loops may provide a useful route to the production of high-affinity TCRs with therapeutic and diagnostic potential.

Keywords: T cell receptor, CDR2, phage display, mutant, high affinity, crystallization, NY ESO 1

The mammalian T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire plays a crucial role in adaptive immunity by recognizing short antigen-derived peptides bound in the context of cell-surface presented major histocompatibility complex (MHC) glycoproteins. In common with antibodies, mature TCR diversity is created through a combination of genomic rearrangements of germ line gene segments and somatic variation mechanisms to generate a huge assembly of potential ligand-recognition specificities. However, unlike antibodies, TCRs do not undergo extensive somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation aimed at generating high-affinity (nanomolar) clonal populations. Indeed, potential high-affinity TCR interactions with self and foreign peptides in the context of self MHC are actively avoided through extensive selective deletion processes that occur in the thymus (Goldrath and Bevan 1999; Starr et al. 2003). As a consequence, it is generally accepted that native monovalent α/β heterodimeric TCRs are characterized by weak (μM) affinities for peptide-MHC (pMHC) and slow kinetics (Davis et al. 1998; Willcox et al. 1999a). The evolution of such a system thus raises the question of how a relatively restricted repertoire of binding entities can effectively recognize and respond to a much larger theoretical array of foreign peptide antigens which, in common with self peptides, are bound in the context of self MHC molecules. A solution to this paradox appears to reside in the discovery that thymically sorted native TCRs possess a measurable degree of promiscuity and potential cross-reactivity (Mason 1998; Wilson et al. 2004; Wucherpfennig 2004). This appears to be mediated by a biased recognition preference for the MHC surface topology combined with a considerable conformational flexibility of the TCR complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), particularly the hypervariable CDR3 loops (Hare et al. 1999; Reiser et al. 2003). Indeed, this suggests a two-step binding mechanism (Wu et al. 2002) whereby the interaction energies are distributed such that initial MHC recognition is followed by specific CDR3-mediated contacts with the peptide. Recently it has also been proposed that the observed ability of model TCRs to recognize many different pMHC ligands can be accounted for by several TCR structural “conformers” existing in equilibrium (Holler and Kranz 2004).

Of particular interest from a protein engineering perspective is the question of whether a native α/β TCR can be engineered to specifically bind its target pMHC with an affinity that exceeds that of the natural in vivo functional KD threshold, which for native TCRs isolated from the peripheral circulation is typically within the range of 1–100 μM (Fremont et al. 1996; Garcia et al. 1997; Willcox et al. 1999b). Recent approaches aimed at engineering higher affinity TCRs in vitro have been influenced by consensus crystallographic structural data that reveals a conserved diagonal docking orientation of the TCR at the pMHC surface, which positions the CDR2 loops over the MHC groove-flanking helices and the CDR3 loops over the bound peptide (reviewed in Rudolph and Wilson 2002). The CDR1 loops appear to have the potential to interact with the termini of the peptide and/or the MHC helices. Although in these complexes TCRs bind to pMHC in similar overall orientation, the shapes and chemical properties of the interacting surfaces are highly diverse, and no conserved contacts between the TCR and the pMHC exist that could determine this generic orientation (Hennecke and Wiley 2001). In addition, such structures reveal that the TCR, while making extensive contacts with the MHC, only interacts with a few key amino acids of the bound peptide such that approximately two thirds of the TCR–pMHC binding energy may be attributable to the TCR–MHC contacts (Manning et al. 1998).

From such structures it becomes apparent that most peptide contacts are potentially made by CDR3 loops, which, by virtue of sequence variation introduced by genetic V-J (α) and V-D-J (β) junctional rearrangements, are likely to be the key determinants of TCR specificity. CDR1 and CDR2 loops, on the other hand, are considered germ line fixed and invariant in a given individual, although polymorphisms between individuals are evident from sequence data (LeFranc and Le-Franc 2001). An energetics study of the well-characterized allogeneic interaction between the murine 2C TCR and the QL9/Ld pMHC using a panel of alanine point-mutated peptides suggested that the CDR3 regions possess the highest potential for improving affinity, as they were shown to contribute less binding energy than did the other loops (Manning et al. 1998). Following on from these observations, Holler et al. (2000) employed an in vitro evolution approach based on a yeast display system in order to select higher affinity CDR3α variants of the murine 2C TCR. Binders were obtained with considerably enhanced affinities, which were shown to retain the fine pMHC specificity of the parent. Interestingly, the authors report that such mutants were isolated from a yeast display library comprising only 105 CDR3α variants. This library size is considerably smaller than the 108 clones statistically required to ensure 99% representation of the intended mutagenic diversity, thus suggesting that higher affinity mutants are abundant and readily obtainable. Using a phage-display based approach, we have extended the utility of CDR mutagenesis and demonstrated the isolation of variant native human TCRs with monovalent affinities in the picomolar range with apparent retention of specificity for cognate self and viral antigens in the syngeneic MHC context of HLA-A*0201 (Li et al. 2005). During our investigations, we chose to explore the potential of the invariant germ line-encoded CDR1 and CDR2 loops in addition to the CDR3s. Previously, it had been suggested that raising the affinity of a TCR by directing the free energy toward the MHC helices could lead to a loss in peptide antigen specificity (Holler et al. 2000). Our aim, therefore, was to investigate whether affinity-enhancing minor-loop mutations, particularly in CDR2, give rise to human TCRs with obviously reduced peptide specificities. Here we report that, contrary to expectations, CDR2-only mutations of a native TCR, specific for a tumor-associated self antigen (derived from NYESO-1; Chen et al. 1997) bound in the context of a class I MHC, are sufficient for high-affinity binding to pMHC in an antigen-dependent fashion with no apparent deleterious consequences for ligand targeting specificity. Furthermore, independently obtained mutations in CDR2α and CDR2β readily combine synergistically to yield spectacular affinity gains over the parent TCR. One such double-CDR2 mutant was found to possess a KD of 1 nM, which represents an enhancement of several thousand-fold over the native parent as determined by surface plasmon resonance measurements. Crystallographic analysis of the ternary TCR–pMHC complex for this clone provides an insight into the nature of the CDR2-mediated affinity gains, and suggests why CDR2 mutagenesis need not compromise binding specificity. In addition, the methods described offer a rapid and convenient route to the manipulation of human TCR affinity for potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Results

First-generation library selections

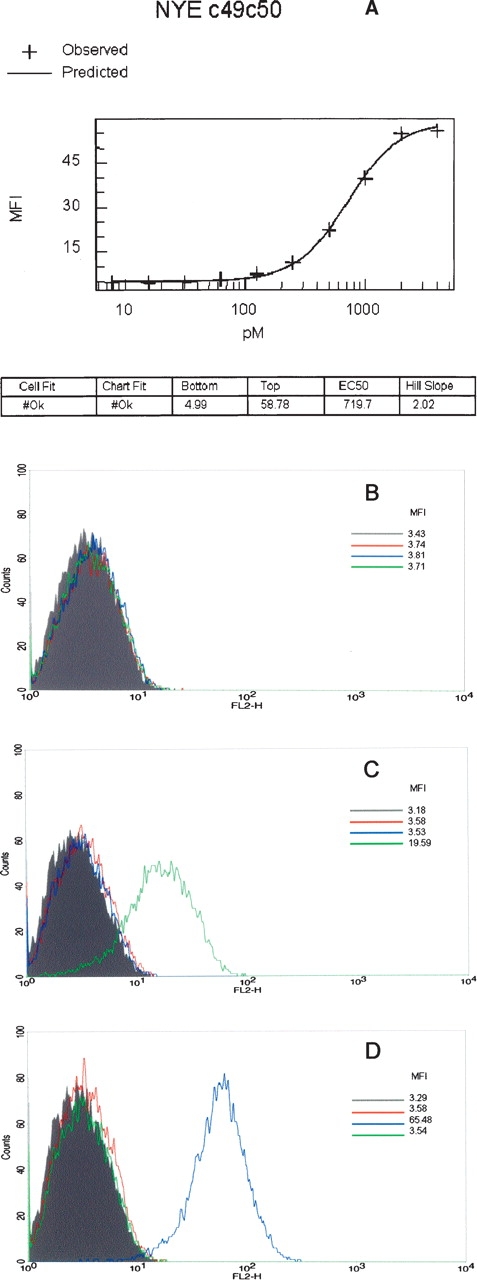

The CDR2α and CDR2β amino acid loops of the human 1G4 parental TCR were randomly mutated to generate two libraries comprising many discrete variants. Both libraries were expressed as gene III fusion proteins on the surface of filamentous phage particles prior to pooling. The pooled phage library was mixed with tumor-associated antigen, NY-ESO-1157–165, bound in the context of biotinylated HLA-A*0201, and any resulting phage–antigen complexes were captured on streptavidin magnetic beads. Bound phage were amplified and enriched through two further cycles of bead-based selection (see Materials and Methods). A total of 352 discrete clones were then individually screened for HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO-1 binding by phage-ELISA. From this population, 20 strong ELISA-positive clones were obtained, representing a hit frequency of ~6%. This was encouraging, as the affinity of the parental 1G4 clone is too weak to register an ELISA signal in this experimental system. These clones were subsequently sequenced, and were found to comprise mutants from both CDR2 libraries (Table 1A). Remarkably, a clear convergence to certain mutations was observed in both CDR2s, with a particularly strong selective enrichment evident for CDR2β where only two sequences were recovered. Perhaps reflecting the exquisite sensitivity of the phage display system employed, both of these mutants contained non-specified primer-synthesis error mutations immediately adjacent to the designated NNK mutagenic region, suggesting strong selective pressure for mutations at this position. In addition, the presence of an NNK-encoded amber stop codon, suppressible to glutamine, in the VAIQT CDR2β mutant (wtc51), did not prevent its multiple occurrence in the third selection cycle output, suggesting that a high intrinsic affinity may have been compensating for a reduced expression/display level. In contrast, the recovered CDR2α mutants were more diverse, with hits resolving into broadly overlapping conserved families. A strong preference for an aromatic/heterocyclic side chain at the third NNK triplet was evident, with tryptophan being particularly favored in place of the germ line-encoded S52 residue. Soluble inhibition phage-ELISA was used to confirm that the isolated phage clones were genuine binders of the NY-ESO-1 pMHC (data not shown). Extending the experiment through a fourth selection cycle saw the ELISA-positive hit frequency increase to ~20%; however, sequencing analysis revealed this population to be monoclonal, with all hits corresponding to the dominant VSVGM (wtc50) CDR2β mutant.

Table 1.

Summary data showing CDR2 mutations obtained from the first and second-generation pooled library experiments

(A) Output clones obtained from three cycles of selection against 100 nM bio-HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO(157–165) (see Materials and Methods).

(B) Output clones obtained from three cycles of selection against 10 nM bio-HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO(157–165) (see Materials and Methods). All CDR2α mutants were found on the c50 CDR2β parental background. From soluble inhibition phage-ELISA experiments, the second-generation mutants shown were inhibited in excess of 90% by 100 nM HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO(157–165). In comparison, the wtc50 positive control background clone showed 70% inhibition.

Q, Amber codon; M/T, nonspecified primer synthesis errors.

aMatching mutant sequences that were recovered from the first-generation experiment.

Second-generation library selections

To further improve the affinity of the discrete CDR2α and CDR2β mutants obtained from the first-generation experiment, the two dominant CDR2β clones (wtc50 and wtc51) and the CDR2α mutant giving the strongest ELISA signals (c49wt) were crossed into the corresponding CDR2 unselected mutant library pool to generate three second-generation libraries. Following pooling of these libraries and three cycles of selection, the ELISA-positive hit frequency was in excess of 90%. A number of the strongest clones were selected for sequencing and soluble inhibition phage-ELISA (Table 1B). All recovered mutants were derived from the c50 background library, confirming the fitness/affinity dominance of the VSVGM CDR2β mutation. Critically, the associated CDR2α mutations were seen to converge, in terms of both homology and identity, toward those that were obtained independently from the first-generation CDR2α library. These data strongly suggest that affinity-enhancing mutations introduced into either CDR2 loop have little or negligible long-range influence on the overall structural organization of the ternary TCR/pMHC interface which, presumably, is determined largely by CDR1/CDR3 contacts (see below).

Affinity and specificity analysis

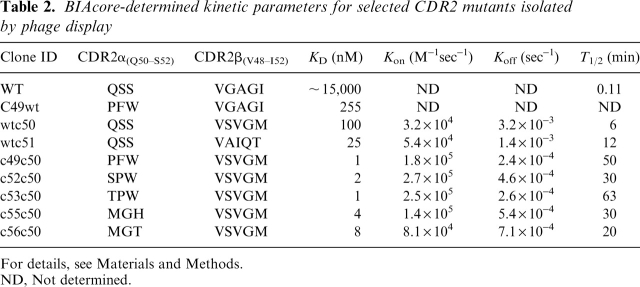

In order to examine the magnitude of the affinity increases for these CDR2 mutants, the discrete Vα and Vβ were reformatted for high-level expression as inclusion bodies. Following refolding and purification, the disulfide stabilized heterodimeric TCRs were subjected to BIAcore SPR binding analysis against immobilized HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO-1 (Table 2). The data reveal equilibrium binding constants that represent dramatic improvements in affinity when compared to the native 1G4 parental TCR. Both Kon and Koff components are seen to contribute to the improved KD values, which for the best clones represent an affinity enhancement of ~15,000-fold. Combining the α chain from c49wt with the dominant wtc50 β chain generated the artificial pairing of c49c50, which yielded a soluble TCR with an affinity of 1 nM. This is equivalent to the highest affinity double CDR2 mutant (c53c50) isolated from the second-generation library experiment. The apparent absence of the c49 PFW mutation from the second-generation output (25 clones sequenced) may, therefore, simply reflect a lack of fitness in the context of selections carried out against a large background population of clones with comparable affinity, rather than any structural incompatibility.

Table 2.

BIAcore-determined kinetic parameters for selected CDR2 mutants isolated by phage display

For details, see Materials and Methods.

ND, Not determined

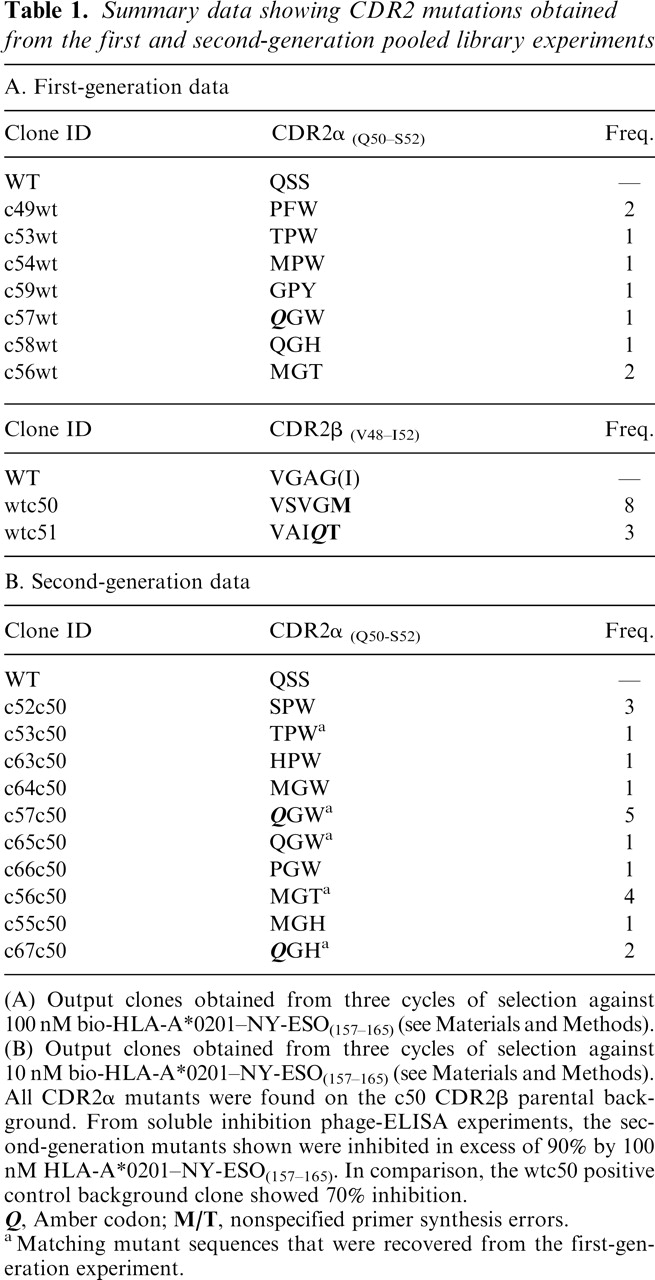

To investigate potential cross-reactivity of the soluble c49c50 TCR, BIAcore binding studies were carried out against a broad panel of 12 distinct self (tumor-associated) and viral peptide antigens bound in the context of HLA-A*0201. None of these antigens showed detectable binding to c49c50 (data not shown). Further investigations were conducted using FACS analysis on HLAA*0201+ cell lines capable of displaying exogenously supplied peptides. Specific, high-affinity, and saturable binding was observed using T2 cells pulsed with the NYESO-1 (V9) peptide (Fig. 1A). These cells are compromised in TAP-dependent processing of endogenous antigens (Smith and Lutz 1996; Luft et al. 2001), and so additional studies were carried out using an HLA-A*0201+ EBV-transformed B-cell line (“PP”), potentially better suited for revealing TCR cross-reactivity. No apparent binding of c49c50 was observed on cells incubated with DMSO (vehicle control) or pulsed with the irrelevant HTLV-1 tax peptide (Fig. 1B,D). The latter served as a positive control in conjunction with the specific CDR3β-mutated high affinity HTLV-1 tax TCR, TAXwtc134, which we have previously shown to have a KD of 2.5nM (Li et al. 2005). Cells pulsed with the wt NY-ESO-1 (C9) peptide are specifically labeled with c49c50 (Fig. 1C) although the degree of staining is reduced when compared to HTLV-1 tax, probably as a consequence of relatively inefficient loading of the MHC by the redox susceptible cysteine-containing native peptide (Chen et al. 2000).

Figure 1.

Specific binding of the high-affinity double CDR2 mutant, c49c50, to peptide-pulsed HLA-A*0201+ cells. (A) Titration binding to T2 cells pulsed with increasing concentrations of NY-ESO-1157–165 “V” variant (SLLMWITQV). FACS staining of HLA-A*0201+ “PP” cells pulsed with either DMSO as vehicle control (B), 10−5 M NY-ESO-1157–165 (C), or 10−5 M HTLV-1 tax11–19 as positive control (D). Pulsed cells were challenged with either c49c50 or TAXwtc134 soluble TCRs (see Materials and Methods). Gray, unstained control; red, 1° and 2° detection antibody control; blue, TAXwtc134 TCR; green, c49c50 TCR. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values are as indicated.

General structural features

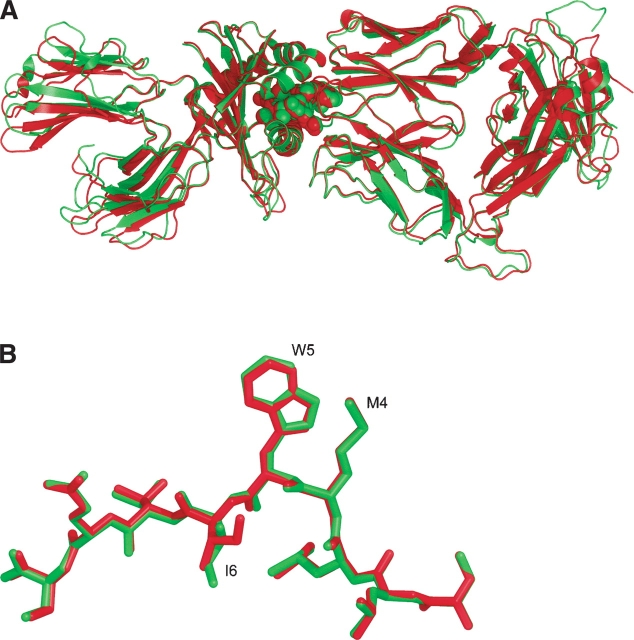

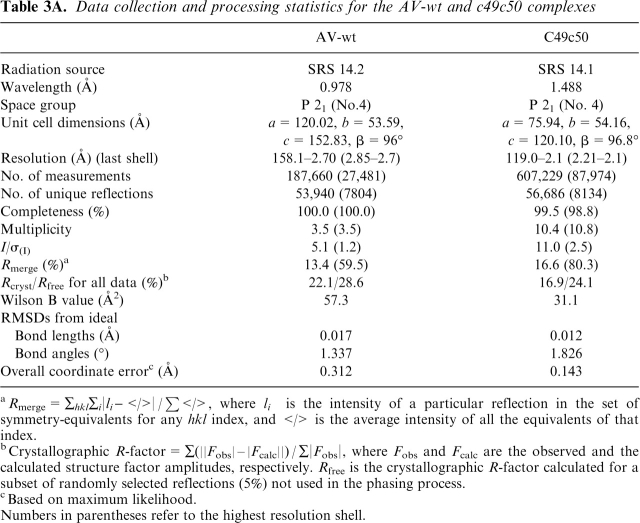

The cell dimensions, space group, and the molecular weight of the complex consistently pointed to the presence of two copies per asymmetric unit for the wild-type structure (AV-wt) and one copy for the mutant. All structural features of the AV-wt and c49c50 complexes were seen to be similar to those of the existing 1G4-pMHC ternary complex, 2BNR (Chen et al. 2005), with no overall significant change of conformation being discernible with RMSD between atomic positions of ~1.0 Å (Fig. 2). The small differences in the unit cell dimensions between 2BNR and the c49c50 complex gave rise to different packing constraints. One consequence was the absence in the mutant of any observable electron density for the C-terminal 14 residues of TCRβ, which were removed from the model. The disorder effect is likely attributable to an artifact of the crystallization conditions. These residues also contain one glycosylation site, usually associated with disorder, although in this case glycosylation was absent as the recombinant protein was produced in Escherichia coli. Structural data collection details are shown in Table 3A.

Figure 2.

Superposition diagrams of the 2BNR and c49c50 mutant complexes. (A) The 2BNR complex is shown in red and the c49c50– pMHC complex is in green. The bound NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide is depicted as spheres. The TCRα C-terminal 14 residues are not visible in the electron density map and are omitted from the final model (see text). (B) Superposition of the peptide from the 2BNR model (red) and c49c50 (green). The side chain of I6 adopts a different conformation, involving an energy neutral rotation about a σ bond. Figures prepared using PyMOL (DeLano 2002).

Table 3A.

A. Data collection and processing statistics for the AV-wt and c49c50 complexes

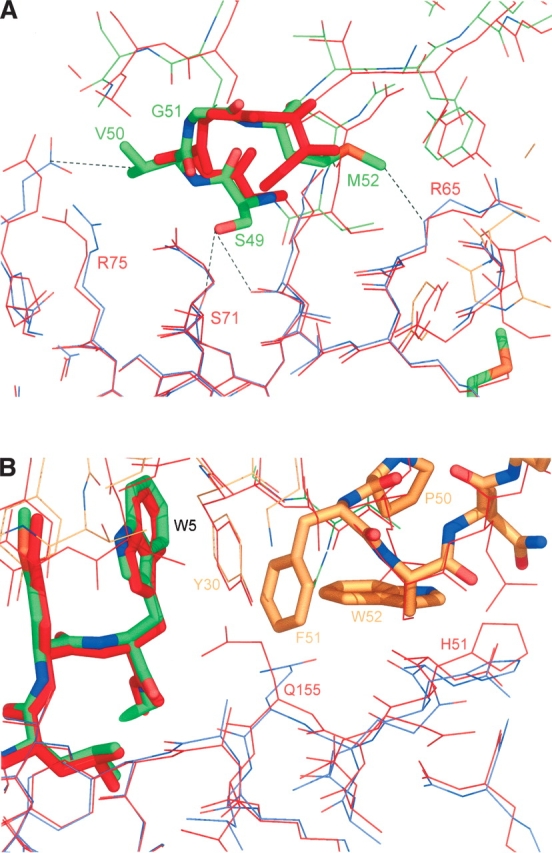

Structural consequences of the c49c50 mutations

CDR2β mutation—Residues 49–52 (GAGI to SVGM)

The overall solvent-accessible surface area at the CDR2β interface did not change relative to that in 2BNR, and no water molecules were expelled. Some minor rearrangements occurred to avoid steric clashes. The loop conformation was also maintained (Fig. 3A). Hence, the higher affinity probably reflects a more favorable charge complementarity at the interface with the MHC α chain. CDR2β residue S49 makes new electrostatic contacts with K68 and S71 of the MHC, V50 makes a nonpolar contact with R75, and M52 makes a nonpolar contact with R65. These compare with a single nonpolar contact between I52 of CDR2β and K68 of the MHC in the 2BNR model.

Figure 3.

Structural depiction of the CDR2 mutant interactions in the c49c50–pMHC complex. (A) The CDR2β loop mutations (GAGI to SVGM). The 2BNR model is depicted in red; the c49c50 TCR is colored by atom type, mostly green; the c49c50 MHC is mostly red. Dotted lines indicate contacts between mutated side chains and MHC residues. (B) The CDR2α loop mutations (QSS to PFW): Q155 of the MHC is pushed deeper into the pocket by the close approach of F51, while W52 forces a tighter packing of the CDR1α Y30 against W5 of the peptide. The 2BNR MHC is red and the c49c50 TCRa is mostly orange. The figures were prepared using PyMOL (DeLano 2002).

CDR2α mutation––Residues 50–52 (QSS to PFW)

An initial assessment suggested that the CDR2α PFW mutation increased the affinity by expanding the buried surface area between the TCR and the peptide-binding groove of the MHC molecule. However, interface calculations revealed that the interface between the MHC and TCRα had shrunk significantly, from 368 Å2 to 335 Å2. The comparison with 2BNR proved counterproductive because it indicated that the global TCR–pMHC interface had also shrunk significantly from 1056 Å2 to 998 Å2. The cell volume of 2BNR was 4.3% larger than that of c49c50, possibly accounting for the larger interface observed in the former. Comparing c49c50 with the AV-wt also proved problematic due to the lower resolution of the AV-wt data and the doubling of one cell dimension to produce two copies in the asymmetric unit. One copy had an interface area that was similar to that seen in 2BNR, while the other was similar to that of the c49c50 mutant at 993 Å2. One other crucial difference was observed between the two copies: Q155, located at the interface between MHC and CDR2α, appears able to adopt two different conformations. In one copy, AV-wt1, it contacts S51 of CDR2α, while in the other copy, AV-wt2, it points toward T94 of TCRα. The area differences between these two interfaces are of the same magnitude as that between 2BNR and c49c50, thus explaining the unreliability of the latter comparison. This region of space in the AV-wt structure is large enough to allow Q155 to select from different partners in an extended pocket lined with opposite charges. One of two possible conformations was observed in 2BNR, while the AV-wt in the present study showed both. This was fortuitous, as the conformation of Q155 in the c49c50 mutant was closer to that of AV-wt2, where the overall TCR– pMHC interface area was of a similar size.

Comparing the TCRα interface with the MHC still showed a significant reduction from AV-wt2 to c49c50 (357 Å2 to 335 Å2). The steric clash of CDR2α F51 with Q155 of the MHC pushed the latter side chain deep into the groove toward T7 of the bound peptide, resulting in the loss of an electrostatic contact with TCRα and an overall reduction of this interface area.

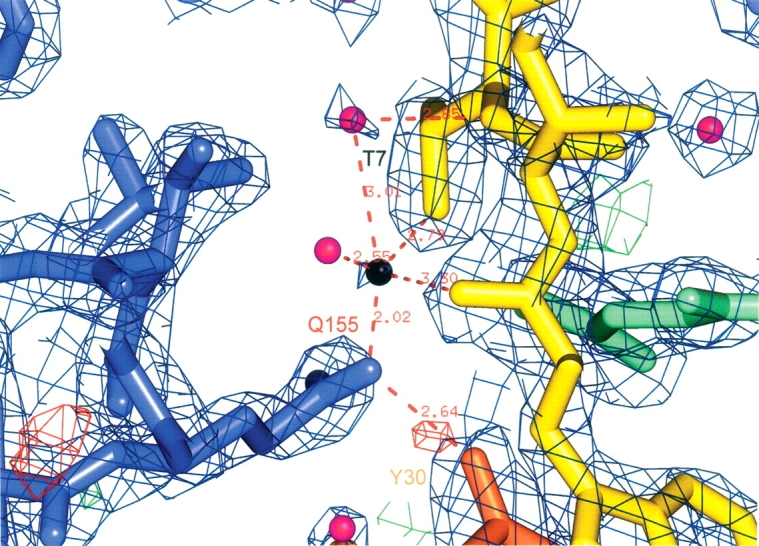

The PFW side chains make new stacking and nonpolar contacts with the side chains of H151 and Q155 of the MHC (Fig. 3B), which were not observed in 2BNR or AV-wt. Residue Q155 now directs its side chain deep into a pocket, close to the peptide, which contained a water molecule in 2BNR. In c49c50, an extra density feature could not be modeled as a water molecule, since it was too close to the Q155 side chain. Alternatively, the observed density may represent an ammonium ion, although how this was acquired by the complex is not clear. Instead, it was modeled as a Na+ ion, which could have been acquired from any of the buffer solutions used in the preparation of the soluble complex/crystals. However, the coordination distances to its surrounding atoms do not conform to any of the metallic species that have been observed previously (Harding 2004). The geometry indicates a bridging effect from Y30 of CDR1α to Q155 of the MHC, through this site, to the T7 side chain of the peptide (Fig. 4). This apparent affinity-enhancing adduct is unlikely to be an artefact of crystallization, and is, to the best of our knowledge, unique for a TCR–pMHC structure. We speculate that it is most likely present due to its co-selection (from the PBS buffer) as a synergist for the PFW mutation during the first-generation phage-display experiment.

Figure 4.

Electron density contoured at 2σ around the identified metal site (black) in the peptide binding groove of the MHC. Some of the approach contacts are indicated. MHC residues are blue. The bound peptide is yellow. TCR α and β chain residues are orange and green, respectively. Water molecules are displayed as purple spheres. The figure was generated using PyMOL (DeLano 2002).

Another feature of the PFW mutation is the close approach of the W52 side chain to the Y30 side chain of the CDR1α, underpinning its stacking interaction with the W5 side chain of the peptide (Fig. 3B). This latter stacking is thus likely to be much more rigid than in the AV-wt structure. Although no direct contact was made between the PFW mutations and the peptide, the contacts described above confer extra stabilization to the new complex in addition to that contributed by the stacking interaction with MHC side chains. Only one solvent site observed in 2BNR near this loop was displaced by the larger side chains. This probably reflects the lack of ordered solvent sites in the AV-wt structure due to significant inter-atomic protein distances. In this case, the mutation appears to have simply filled up meso-space and bridged the TCR to the MHC.

The MHC-bound peptide contacts remain essentially unaltered, with solvent sites commonly occupied and having very similar approach distances in the two structures. The peptide C9 residue is clear of the protein environment, and therefore unlikely to form a covalent bond through its reactive thiol group. A significant difference was the newly identified putative metal site and the rearrangement of the Q155 side chain, as outlined above.

The overall change in the interface area between the TCR and the pMHC is negligible when comparing AV-wt2 with c49c50. The reduction in the TCRα–MHC component of the interface is balanced by an increase in the TCRβ–MHC interface from 441 Å2 to 483 Å2.

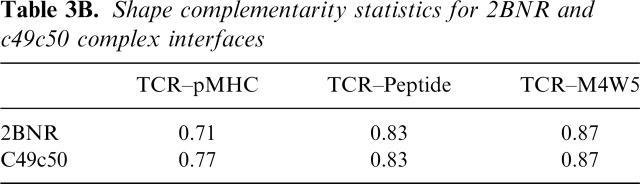

Shape complementarity calculations

The degree of geometrical fit for the various interfaces was also calculated (Table 3B). Shape complementarity, calculated with Sc (Lawrence and Colman 1993) is very high for the TCR/peptide interface at 0.83. Residues M4 and W5 of the bound peptide form a recognition epitope that projects out above the surface of the MHC. When the interface of this dipeptide alone with the TCR is considered, Sc is even higher at 0.87. These values are the same as in 2BNR, i.e., there is no difference in the geometrical fit. The most salient feature, however, is highlighted when the interface between the TCR and the MHC as a whole is considered. The increase in Sc from 0.71 in 2BNR to 0.77 in the c49c50–pMHC complex is a significant enhancement, and suggests that this feature contributes substantially to the increased TCR affinity. The Sc values for AV-wt1 and AV-wt2 are very similar to those of 2BNR.

Table 3B.

Shape complementarity statistics for 2BNR and c49c50 complex interfaces

aRmerge = ∑hkl∑i|li - </>| / ∑</>, where li is the intensity of a particular reflection in the set of symmetry-equivalents for any hkl index, and </> is the average intensity of all the equivalents of that index.

bCrystallographic R-factor = ∑(||Fobs|–|Fcalc||) / ∑ |Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and the calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively. Rfree is the crystallographic R-factor calculated for a subset of randomly selected reflections (5%) not used in the phasing process.

cBased on maximum likelihood.

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

Discussion

Shared features of TCR and antibody gene rearrangement biology indicate that the theoretical TCR clone repertoire available to any individual is huge, possibly in the order of 1014 different structures (Davis and Bjorkman 1988). However, prior to their maturation and release into the peripheral circulation, an individual's TCR-bearing thymocytes are subjected to an extraordinary and enigmatic sorting process that eliminates the vast majority of this potential. Indeed, one sophisticated study estimates that the mature T cell repertoire may comprise as few as 25 million distinct TCRs (Arstila et al. 1999).

This highly specialized cohort of cells are tuned to recognize foreign organism-derived peptides bound to self MHC, but not to appreciably interact with self-derived pMHC complexes in healthy individuals. The mechanisms by which this surveillance system maintains a bias for self MHC alleles and yet can discriminate between bound peptides that occupy ~25% of the TCR interaction surface (typically 1300–2000 Å2 of buried solvent-accessible area) (Rudolph and Wilson 2002) are not clear. However, a number of elegant studies suggest that the germ line encoded TCR variable elements are predisposed to recognize certain generic features common to all MHC molecules (Huseby et al. 2003, 2005). Indeed, in transgenic mouse models where normal thymic sorting is compromised, T cell repertoires appear to display considerable cross-reactivity for peptide and MHC, as do T cell hybridomas expressing randomly paired α and β chains (Blackman et al. 1986). Further, it has been shown that the specificity of a wild-type human TCR that is promiscuous for an influenza peptide bound in the context of several different class II HLA (DR) alleles is dramatically altered in transfected cells containing only a single conserved point mutation in CDR2α (Brawley and Concannon 1996). A more striking example of a single CDR2α point mutation was demonstrated in a transgenic mouse study (Blander et al. 2000) where a global shift in T cell differentiation from Th1 to Th2 was observed. Hence, it would appear from a consideration of the biology that in vitro manipulation of TCR germ line sequences may have profound implications for the specificity of pMHC recognition.

The current study has attempted to address whether the physiological plasticity/cross-reactivity observed at the level of the intact T cell limits the utility of the germ line CDR2 loops in directed evolution approaches. We have engineered a native TCR, in this case with specificity for the tumor-associated NY-ESO-1 self antigen, for increased affinity by exploiting the interaction energy between the TCR CDR2 loops and the MHC surface. Structural comparison of the c49c50 double-CDR2 mutant with the native parent reveals that the CDR2 mutations do not result in a global rearrangement of the TCR–pMHC interface. Furthermore, the principal determinants of pMHC specificity, namely the conformations of the CDR3 loops over the peptide, remain essentially unchanged. The magnitude of the affinity gain induced with these mutations and the substantial improvement in surface complementarity with the MHC raised the possibility that c49c50 would display readily observable and general cross-reactivity with other peptide-HLA-A*0201 molecules. However, no evidence for nonspecific binding could be detected either by discrete SPR analysis or from pulsed cell staining. Insights into why such apparent specificity is maintained may be gained from an inspection of existing TCR–pMHC structural data, namely, the two available HLA-A*0201 structures bound to the HTLV-1 tax11–19 peptide (PDB accession codes 1AO7, 1BD2) (Garboczi et al. 1996; Ding et al. 1998). In both cases, the respective native TCR clones, A6 and B7, possess the TRBV 6–5 determinant in common with the 1G4 clone, and thus share the same CDR2β loop. However, in these complexes, all three TRBV 6–5 chains differ dramatically in the positioning of their CDR2β loops over the MHC, with the most extreme case being that of the CDR2β loop of the A6 clone, which makes no apparent contact with the surface of the MHC. Extending the structural analysis to a larger collection of TCR–pMHC complexes (for review, see Rudolph and Wilson 2002), reveals that the apparently conserved diagonal binding mode of the TCR is rather flexible, with the long axis of the TCR adopting an angle between 45° and 70° relative to the peptide axis. Such a differential “twist” of the TCR relative to the MHC surface is clearly evident in the A6 and B7 complexes despite the common b chain germ line CDRs. In addition, the overall inclination of the TCR (“roll,” “tilt”) on the MHC surface is shown to vary significantly between structures, suggesting that fine-resolution positioning is highly variable/tuneable, and may be distinct for any given TCR–pMHC interaction. Such subtle plasticity of binding is presumably determined not only by the α and β framework pairings but also by the hypervariable CDR3 loops. These, by virtue of a considerable degree of conformational flexibility combined with an absence of defined binding sites for germ line CDRs on the MHC, are likely to play a prominent role in determining the orientation of other elements of the TCR over the MHC. Indeed, the fact that no “codon-like” binding relationships have been established for TCR germ line CDRs and MHC molecules suggests that rather than leading to a dangerously strengthened set of conserved MHC interactions, mutagenesis of CDR2s may redirect the interaction energy from a rather degenerate and weak topological “sensing” of pMHC surfaces to a local site-specific interaction of the kind exemplified by many antibody–antigen interactions.

We have extended our CDR2-directed evolution analysis to other native, thymically-sorted TCRs recognizing class I pMHC complexes (data not shown) and observed similar retention of specificity with dramatically increased affinity. In one striking example, a TCR directed toward the HLA-A*0201-bound p540 epitope of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (ILAK FLHWL; Vonderheide et al. 1999) with a native KD of ~35 μM, was affinity enhanced 14,000-fold following mutagenesis of only the CDR2β. Significantly, despite this TCR possessing the TRBV 6–5 β chain, the high-affinity CDR2 mutations obtained share no sequence homology/similarity with the 1G4 CDR2β mutations described above, and do not show cross-reactivity with other pHLA-A*0201 complexes (data not shown).

In summary, we propose that CDR2-mutated monovalent TCR molecules may have utility as diagnostic or therapeutic targeting reagents for surface-presented pMHC complexes. Our data suggest that high affinity can be readily achieved through directed evolution of germ line CDR2s, and that such mutations need not compromise selectivity for the bound peptide antigen. The structural basis for one such mutant bound to the cognate HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO-1 complex appears to be determined by mechanisms that do not involve the peptide directly, with the principal quantifiable gains arising from significantly improved surface complementarity. Recently, a report describing the generation of a single improved affinity CDR2α variant of the murine model 2C TCR was published (Chlewicki et al. 2005). In agreement with our observations, the authors found that this mutant appeared to retain a high degree of specificity. From a consideration of the phage display process, CDR2 mutagenesis offers the advantage that complete randomization of CDR2 loop amino acids is generally achieved using smaller mutant libraries than for CDR3s, which, often being significantly longer, require large multiple overlapping libraries in order to isolate high-affinity binders. In addition, we have shown that high-affinity CDR2 mutations can be combined synergistically with independently obtained CDR3 mutants yielding pico-molar affinities (Li et al. 2005). A caveat, however, is that although the CDR2 mutants that we describe possess the advantage of retaining native CDR3 sequences that have been filtered for deleterious cross-reactivity by the thymus, it remains to be seen whether such molecules retain physiological specificity in the context of a transfected T cell, for which cytotoxic activation thresholds may be considerably lower than SPR or cell-staining detection sensitivities.

Materials and Methods

Human T cell receptor and pMHC

The wild-type TCR clone 1G4 was obtained from V. Cerundolo (Oxford University, UK) and recognizes the tumor-associated antigen NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide (SLLMWITQC) in the context of HLA-A*0201. Biotinylated and nonbiotinylated pMHC complexes were prepared as previously described (Garboczi et al. 1992).

Library construction

The rearranged Vα and Vβ open reading frames of the native 1G4 TCR (TRAV21, TRBV6–5) (nomenclature according to LeFranc and LeFranc 2001) were cloned into a phagemid vector, pEX922, adjacent to their respective vector-encoded Cα and Cβ domains that had been modified to allow disulfide-assisted heterodimerization of the two chains (Boulter et al. 2003). In our system, the Cβ domain is fused N-terminally to M13 bacteriophage gene III, and periplasmic expression leader sequences are incorporated N-terminally to the introduced Vα and Vβ domains. Using the parental 1G4 phagemid vector as a template, mutagenized CDR2α and CDR2β loop regions were prepared using PCR amplification with mutagenic oligonucleotides as forward primers, and downstream fully complementary oligonucleotides as reverse primers to generate a population of mutated fragments for each of the two CDR2s. For CDR2α, the core three residues were randomized; for CDR2β, the core four residues were randomized. Additional overlapping fragments were generated to allow splicing by overlap extension in order to introduce convenient restriction sites for subsequent library construction. Each spliced PCR fragment containing the respective CDR2 mutant repertoire was digested with appropriate cloning site enzymes and ligated into similarly digested parental pEX922:1G4 to generate independent CDR2α and CDR2β 1G4 library DNA. Electroporation into E. coli TG1 cells and subsequent library phage rescue were carried out according to standard procedures. Both libraries were ~107 in size, and considerably larger than the theoretically encoded repertoires. Second-generation libraries using discrete CDR2 hits of interest as the new “parental” template vectors were similarly constructed.

Isolation of high-affinity mutants

Rescued library phage from first-or second-generation CDR2 libraries were pooled and preblocked with 2% skimmed milk/ 1% BSA in PBS. Subsequently, 10–100 nM biotinylated HLAA*0201–NY-ESO-1 was added to the phage and solution binding allowed to occur. After 1 h at room temperature, complexes were captured by the addition of preblocked streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads. Following magnetic precipitation, beads were washed (3× PBS + 3× PBS/0.1% Tween20), resuspended in PBS, and added directly to exponentially growing TG1 cells in the presence of 2% glucose. Passive infection was allowed to proceed for 1–2 h at 37°C. Infected cells were precipitated and expanded in liquid culture in the presence of ampicillin and glucose to complete a selection cycle. Subsequently, TCR-displaying phage particles were rescued from these cells according to standard procedures, and were fed back into a second cycle of selection. In total, three to four cycles of selection were performed before resultant discrete ampicillin-resistant clones were subjected to conventional micro-well phage-ELISA screening against immobilized biotinylated HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO-1. Promising hits were assessed for relative affinity by soluble inhibition ELISA using various concentrations of nonbiotinylated HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO-1.

Soluble protein production and characterization of affinity/specificity

Soluble TCR mutants of interest were produced as disulfide-linked heterodimers from denatured inclusion body refolds as previously described (Boulter et al. 2003). Suppressible amber stop codons occurring in isolated phagemid clones were mutated back to glutamine prior to introduction of TCR chains (minus the phagemid encoded periplasmic leader sequences) into the expression plasmid pGMT7. Production of insoluble inclusion bodies utilized the nonsuppressor E. coli strain BL-21 (Rosetta pLysS; Novagen). Column-purified TCR heterodimers were quality checked by SDS-PAGE and subjected to SPR affinity analysis on a BIAcore3000 (BIAcore AB). Briefly, streptavidin was covalently coupled to BIAcore CM-5 sensor chip surfaces using standard amine coupling chemistry. Two ethanolamine-blocked chip flow cells were then loaded with 300–400 RUs of biotinylated HLA-A*0201– NY-ESO-1 and two flow cells left blank, prior to blocking excess streptavidin sites on the chip with free biotin. Diluted TCR proteins (200–1500 nM) were injected at 50 μL/min using the Kinject function. Parallel injections were carried out across both HLA-immobilized and blank flow cells. Kinetic analysis of the blank-subtracted data was performed using the BIA-evaluation software. Origin software (OriginLab) was used for T1/2 determination. Under the employed conditions, mass transport and rebinding artefacts were not observed.

Cell staining

The FACS staining protocol was as follows: HLA-A*0201+ “PP” cells (an EBV-transformed B-cell line purchased from Scott Burrows, University of Queensland) were pulsed with either 10−5 M positive control HTLV-1 tax11–19 (LLFGYPVYV) (Elovaara et al. 1993), 10−5 M NY-ESO-1157–165 (SLLMWITQC), or DMSO (vehicle control) for 90 min at 37°C. After a wash step, cells (0.2× 106) were left unstained or incubated with either a high-affinity tax TCR,TAXwtc134 (2.5 μg/mL), or the 1G4 double CDR2 mutant, c49c50 (10 μg/mL). The cells were washed, and bound TCR was detected by incubating with anti-TCR 1°Ab (Clone W4F.5B, ATCC number HB9282) for 15 min at room temperature. After washing, the cells were incubated with RPE-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragment of rabbit anti-mouse antibody (DAKO RO439;10 μg/mL) for 15 min at room temperature. Following incubation, cells were washed, and TCR binding was examined by flow cytometry using a FACS Vantage SE (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using WinMDI. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values are as indicated.

The TCR titration protocol was as follows: HLA-A*0201+ T2 cells (a TAP-deficient TB hybridoma) were pulsed with either 10−6 M NY-ESO-1157–165 “ V” variant (SLLMWITQV), or DMSO (vehicle control) for 90 min at 37°C. After a wash step, cells (0.2× 106) were left unstained or incubated with the 1G4 double CDR2 mutant, c49c50, at the concentration indicated for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were washed and bound TCR was detected by incubating with anti-TCR 1°Ab (Clone W4F.5B, ATCC number HB9282) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, the cells were incubated with RPE-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragment of rabbit anti-mouse antibody (DAKO RO439;10 μg/mL) for 30 min at room temperature. Following incubation, cells were washed and TCR binding was examined by flow cytometry using a FACS Vantage SE (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using WinMDI. MFI values are as indicated.

Crystallization of the 1G4 wild-type (AV-wt) and double CDR2 mutant c49c50 complexed with HLA-A*0201–NY-ESO-1

Refolded inclusion body-derived proteins (AV-wt/c49c50 TCR and pMHC) were mixed together in a 1:1 molar stoichiometry and purified using S200HR size-exclusion chromatography (GE Healthcare) into 10 mM Tris (pH 8), 10 mM NaCl. The peak corresponding to the ternary complex (~100 kDa) was concentrated down to 15 mg/mL using 10-kDa centrifugal concentrators. Hampton Research Crystal Screen Cryo solutions were used in crystallization trials employing the vapor diffusion method, and yielded several hits. No further optimization was conducted. Crystals of the AV-wt and c49c50 pMHC complexes grown under condition 41 (85 mM Na-HEPES buffer at pH 7.5, 8.5% iso-propanol, 17% PEG 4000, 15% glycerol) diffracted to 2.7 Å and 2.1 Å resolution, respectively. Data collection details are in Table 3A.

Data collection and reduction

Single crystals of the AV-wt or c49c50 TCR–pMHC complex measuring up to 200 × 200 × 100 μm were mounted in thin nylon loops and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen. One crystal of the wild-type complex was used at SRS Station 14.2 (Dares-bury Laboratory), and three crystals of the mutant complex were used at SRS Station 14.1. Each crystal was set in a random orientation and a complete data set collected on an ADSC Q4 CCD detector, with the rotation method, at an exposure rate of 30–90 sec per 1° rotation. Diffraction was observed generally up to 2.5 Å for the AV-wt complex and up to 2.0 Å or higher for the mutant, but merging was cut off at 2.7 Å and 2.1 Å, respectively, beyond which the statistics were not reliable. The relevant statistics are included in Table 1. MOSFLM was used to process the data set, SCALA for merging and reducing the data set to the unique indices, and TRUNCATE for producing amplitudes and relevant statistics (CCP4 program suite; CCP4 1994).

Structure solution and refinement

The AV-wt structure was solved with molecular replacement methods using AMoRe (Navaza 2001). The probe model was taken from PDB entry 1BD2 (Ding et al. 1998). Two copies were located in the asymmetric unit. The native 1G4–pMHC ternary complex (Chen et al. 2005) (PDB entry 2BNR), which has an identical sequence to the AV-wt in the present study, and crystallized under similar conditions, was used as a search probe to solve the structure of the mutant using molecular replacement. Only one solution was found in this case, with an initial R-factor of 45.6%. Rigid-body refinement, followed by rounds of restrained positional and thermal parameters refinement with REFMAC5 (CCP4 1994), and model adjustment in graphics sessions using O (Jones et al. 1991), resulted in a refined model with average geometrical deviations from ideal within the expected range. Completion of the structural analysis was performed with the CCP4 suite.

PDB submission

The AV-wt and the high-affinity c49c50 mutant have been submitted to the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession numbers 2F54 and 2F53, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Molloy for helpful advice and comments, and Tracey Miles for assisting with the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Bent K. Jakobsen, Avidex Limited, 57C Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RX, UK; e-mail: Bent.Jakobsen@avidex.com; fax: 44-(0)1235-438650.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051936406.

References

- Arstila T.P., Casrouge A., Baron V., Even J., Kanellopoulos J., Kourilsky P. 1999. A direct estimate of the human αβ T cell receptor diversity Science 286: 958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman M., Yague J., Kubo R., Gay D., Coleclough C., Palmer E., Kappler J., Marrack P. 1986. The T cell repertoire may be biased in favor of MHC recognition Cell 47: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander J.M., Sant'Angelo D.B., Bottomly K., Janeway C.A. Jr. 2000. Alteration at a single amino acid residue in the T cell receptor a chain complementarity determining region 2 changes the differentiation of naive CD4 T cells in response to antigen from T helper cell type 1 (Th1) to Th2 J. Exp. Med. 191: 2065–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter J.M., Glick M., Todorov P.T., Baston E., Sami M., Rizkallah P., Jakobsen B.K. 2003. Stable, soluble T-cell receptor molecules for crystallization and therapeutics Protein Eng. 16: 707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley J.V. and Concannon P. 1996. Modulation of promiscuous T cell receptor recognition by mutagenesis of CDR2 residues J. Exp. Med. 183: 2043–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CCP4 (Collaborative Computational Project Number 4). 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50: 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.T., Scanlan M.J., Sahin U., Tureci O., Gure A.O., Tsang S., Williamson B., Stockert E., Pfreundschuh M., Old L.J. 1997. A testicular antigen aberrantly expressed in human cancers detected by autologous antibody screening Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 1914–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.L., Dunbar P.R., Gileadi U., Jager E., Gnjatic S., Nagata Y., Stockert E., Panicali D.L., Chen Y.T., Knuth A. 2000. Identification of NY-ESO-1 peptide analogues capable of improved stimulation of tumor-reactive CTL J. Immunol. 165: 948–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.L., Stewart-Jones G., Bossi G., Lissin N.M., Wooldridge L., Choi E.M., Held G., Dunbar P.R., Esnouf R.M., Sami M.et al. 2005. Structural and kinetic basis for heightened immunogenicity of T cell vaccines J. Exp. Med. 201: 1243–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlewicki L.K., Holler P.D., Monti B.C., Clutter M.R., Kranz D.M.et al. 2005. High-affinity, peptide-specific T cell receptors can be generated by mutations in CDR1, CDR2 or CDR3 J. Mol. Biol. 346: 223–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.M. and Bjorkman P.J. 1988. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition Nature 334: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.M., Boniface J.J., Reich Z., Lyons D., Hampl J., Arden B., Chien Y. 1998. Ligand recognition by α β T cell receptors Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16: 523–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. In http://www.pymol.org.

- Ding Y.H., Smith K.J., Garboczi D.N., Utz U., Biddison W.E., Wiley D.C. 1998. Two human T cell receptors bind in a similar diagonal mode to the HLA-A2/Tax peptide complex using different TCR amino acids Immunity 8: 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elovaara I., Koenig S., Brewah A.Y., Woods R.M., Lehky T., Jacobson S. 1993. High human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-specific precursor cytotoxic T lymphocyte frequencies in patients with HTLV-1-associated neurological disease J. Exp. Med. 177: 1567–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremont D.H., Rees W.A., Kozono H. 1996. Biophysical studies of T-cell receptors and their ligands Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garboczi D.N., Hung D.T., Wiley D.C. 1992. HLA-A2-peptide complexes: Refolding and crystallization of molecules expressed in Escherichia coli and complexed with single antigenic peptides Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89: 3429–3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garboczi D.N., Ghosh P., Utz U., Fan Q.R., Biddison W.E., Wiley D.C. 1996. Structure of the complex between human T-cell receptor, viral peptide and HLA-A2 Nature 384: 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia K.C., Tallquist M.D., Pease L.R., Brunmark A., Scott C.A., Degano M., Stura E.A., Peterson P.A., Wilson I.A., Teyton L. 1997. ab T cell receptor interactions with syngeneic and allogeneic ligandsAffinity measurements and crystallization Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94: 13838–13843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldrath A.W. and Bevan M.J. 1999. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire Nature 402: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding M.M. 2004. The architecture of metal coordination groups in proteins Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60: 849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare B.J., Wyss D.F., Osburne M.S., Kern P.S., Reinherz E.L., Wagner G. 1999. Structure, specificity and CDR mobility of a class II restricted single-chain T-cell receptor Nat. Struct. Biol. 6: 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennecke J. and Wiley D.C. 2001. T cell receptor-MHC interactions up close Cell 104: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler P.D. and Kranz D.M. 2004. T cell receptors: Affinities, cross-reactivities, and a conformer model Mol. Immunol. 40: 1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler P.D., Holman P.O., Shusta E.V., O'Herrin S., Wittrup K.D., Kranz D.M. 2000. In vitro evolution of a T cell receptor with high affinity for peptide/MHC Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 5387–5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseby E.S., Crawford F., White J., Kappler J., Marrack P. 2003. Negative selection imparts peptide specificity to the mature T cell repertoire Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 11565–11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseby E.S., White J., Crawford F., Vass T., Becker D., Pinilla C., Marrack P., Kappler J.W. 2005. How the T cell repertoire becomes peptide and MHC specific Cell 122: 247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou J.Y., Cowan S.W., Kjeldgaard M. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models Acta Crystallogr. A 47: 110–119 Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M.C. and Colman P.M. 1993. Shape complementarity at protein/protein interfaces J. Mol. Biol. 234: 946–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFranc M. P. and LeFranc G. In The T cell receptor facts book. . 2001. Academic Press, New York.

- Li Y., Moysey R., Molloy P.E., Vuidepot A.L., Mahon T., Baston E., Dunn S., Liddy N., Jacob J., Jakobsen B.K. 2005. Directed evolution of human T-cell receptors with picomolar affinities by phage display Nat. Biotechnol. 23: 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft T., Rizkalla M., Tai T.Y., Chen Q., MacFarlan R.I., Davis I.D., Maraskovsky E., Cebon J.et al. 2001. Exogenous peptides presented by transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP)-deficient and TAP-competent cells: Intracellular loading and kinetics of presentation J. Immunol. 167: 2529–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning T.C., Schlueter C.J., Brodnicki T.C., Parke E.A., Speir J.A., Garcia K.C., Teyton L., Wilson I.A., Kranz D.M. 1998. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of an ab T cell receptor: Mapping the energy of antigen recognition Immunity 8: 413–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason D. 1998. A very high level of crossreactivity is an essential feature of the T-cell receptor Immunol. Today 19: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. 2001. Implementation of molecular replacement in AMoRe Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57: 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser J.B., Darnault C., Gregoire C., Mosser T., Mazza G., Kearney A., van der Merwe P.A., Fontecilla-Camps J.C., Housset D., Malissen B. 2003. CDR3 loop flexibility contributes to the degeneracy of TCR recognition Nat. Immunol. 4: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph M.G. and Wilson I.A. 2002. The specificity of TCR/pMHC interaction Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14: 52–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.D. and Lutz C.T. 1996. Peptide-dependent expression of HLA B7 on antigen processing-deficient T2 cells J. Immunol. 156: 3755–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr T.K., Jameson S.C., Hogquist K.A. 2003. Positive and negative selection of T cells Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21: 139–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonderheide R.H., Hahn W.C., Schultze J.L., Nadler L.M. 1999. The telomerase catalytic subunit is a widely expressed tumor-associated antigen recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes Immunity 10: 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox B.E., Gao G.F., Wyer J.R., Ladbury J.E., Bell J.I., Jakobsen B.K., van der Merwe P.A. 1999a. TCR binding to peptide-MHC stabilizes a flexible recognition interface Immunity 10: 357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox B.E., Gao G.F., Wyer J.R., O'Callaghan C.A., Boulter J.M., Jones E.Y., van der Merwe P.A., Bell J.I., Jakobsen B.K. 1999b. Production of soluble ab T-cell receptor heterodimers suitable for biophysical analysis of ligand binding Protein Sci. 8: 2418–2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.B., Wilson D.H., Schroder K., Pinilla C., Blondelle S., Houghten R.A., Garcia K.C. 2004. Specificity and degeneracy of T cells Mol. Immunol. 40: 1047–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L.C., Tuot D.S., Lyons D.S., Garcia K.C., Davis M.M. 2002. Two-step binding mechanism for T-cell receptor recognition of peptide MHC Nature 418: 552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wucherpfennig K.W. 2004. Presentation of a self-peptide in two distinct conformations by a disease-associated HLA-B27 subtype J. Exp. Med. 199: 151–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]