Abstract

TTHA0727 is a conserved hypothetical protein from Thermus thermophilus HB8, with a molecular mass of 12.6 kDa. TTHA0727 belongs to the carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase (CMD) family (Pfam 02627). A sequence comparison with its homologs suggested that TTHA0727 is a distinct protein from alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD and γ-carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase in the CMD family. Here we report the 1.9 Å crystal structure of TTHA0727 (PDB ID: 2CWQ) determined by the multiwavelength anomalous dispersion method. The TTHA0727 monomer structure consists of seven α-helices (α1–α7) and one short 310-helix. The crystal structure and the analytical ultracentrifugation revealed that TTHA0727 forms a hexameric ring structure in solution. The electrostatic potential distribution on the solvent-accessible surface of the TTHA0727 hexamer showed that positively charged regions exist on the side of the ring structure, suggesting that TTHA0727 interacts with some negatively charged molecules. A structural homology search revealed that the structure of three α-helices (α4–α6) is remarkably conserved, suggesting that it is the common structural motif for the CMD family proteins. In addition, the nine residues of the N-terminal tag bound to the cleft region between α1 and α3 in chains A and B of TTHA0727, implying that this region is the putative binding/active site for some small molecules.

Keywords: extremely thermophilic bacteria, Thermus thermophilus HB8, hypothetical protein, TTHA0727 (TT1628), carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase (CMD) family, hexameric ring structure, structural genomics/proteomics

The genome sequence of the extremely thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus HB8, published by the Structural-Biological Whole Cell Project (www.thermus.org), revealed that over one-third of the 2238 proteins encoded by the genome are hypothetical proteins. TTHA0727 from T. thermophilus HB8 (gi:55980696) is a conserved hypothetical protein, which consists of 117 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of 12.6 kDa. The hypothetical protein TTC0375, with the same amino acid sequence, also exists in T. thermophilus HB27 (gi:46198683) (Henne et al. 2004). TTHA0727 homologs are conserved among several prokaryotes (Fig. 1A). The TTHA0727 protein shares 35%, 29%, and 23% identities to the alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD core from Moorella thermoacetica ATCC 39073 (gi:68239079), the hypothetical protein AF0348 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus DSM 4304 (gi:11497960) (Klenk et al. 1997), and the AhpD core from Mesorhizobium sp. BNC1 (gi:68193778), respectively. TTHA0727 belongs to the carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase (CMD) family in the Pfam database (Pfam02627, E-value = 7e-6, hit region 29–116). In the CMD family, γ-carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase (γ-CMD) and alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD are the representative proteins. γ-CMD catalyzes the decarboxylation of γ-carboxymuconolactone to β-ketoadipate enol-lactone, in the catabolism of aromatic compounds through the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway (EC 4.1.1.44) (Stanier and Ornston 1973). In T. thermophilus HB8, there is another CMD family protein, TTHA1508, which shares 11% identity with TTHA0727. TTHA1508 is probably γ-CMD, because of its high homology with the γ-CMDs of other species (identity = 30% ∼ 50%), although the active site residues of γ-CMD have not been determined. It is unlikely that TTHA0727 is γ-CMD itself, due to its relatively low homology (identity = 10% ∼ 20%). On the other hand, AhpD has peroxidase activity and is involved in an antioxidant defense mechanism (Bryk et al. 2002). AhpD has a thioredoxin-like active site, a Cys-X-X-Cys motif (Cys 130 and Cys 133), which is critical for the peroxidase activity. However, the catalytic Cys 130 residue of AhpD is replaced with Ser 70 at the corresponding site in TTHA0727, indicating that TTHA0727 lacks peroxidase activity. In the CMD family proteins, TTHA0727 is a distinct protein from AhpD and γ-CMD, and its function is unknown. To analyze the structural properties of TTHA0727, we determined the crystal structure of TTHA0727 by the multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) method (Hendrickson 1991) at 1.9 Å resolution.

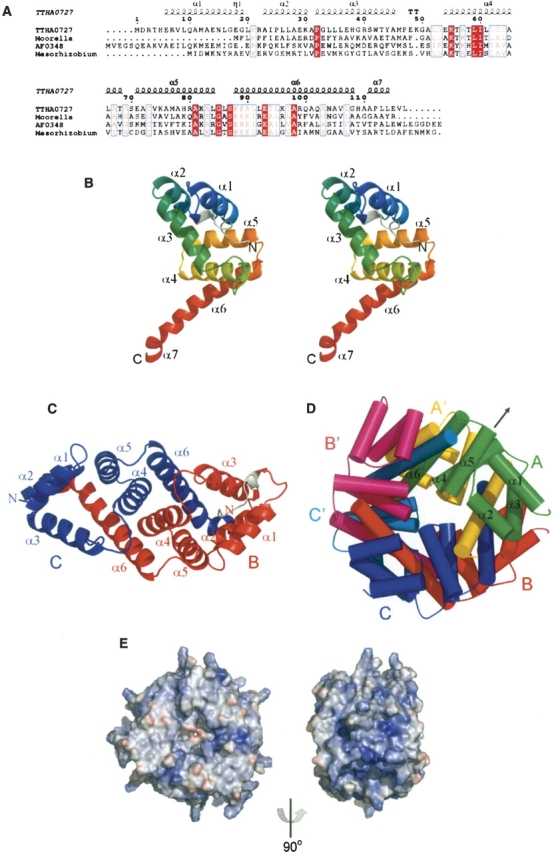

Figure 1.

(Legend on previous page)(A) Sequence alignment of TTHA0727 homologs. (TTHA0727) Hypothetical proteins TTHA0727 from Thermus thermophilus HB8 (gi:55980696) and TTC0375 from T. thermophilus HB27 (gi:46198683); (Moorella) alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD core from Moorella thermoacetica ATCC 39073 (gi:68239079); (AF0348) hypothetical protein AF0348 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus DSM 4304 (gi:11497960); (Mesorhizobium) alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD core from Mesorhizobium sp. BNC1 (gi:68193778). The alignment was generated by ESPript (Gouet et al. 1999) with CLUSTALW (Thompson et al. 1994). The secondary structures of the TTHA0727 protein, as determined by DSSP (Kabsch and Sander 1983), are shown above the sequences (α, α-helix; η, 310-helix; TT, β-turn). (B) Ribbon representation of the TTHA0727 monomer (chain A) (stereoview). Color gradient (blue, green, yellow, red) from the N terminus to the C terminus. The extra residues of the N-terminal tag are colored gray. (C) Ribbon representation of a TTHA0727 dimer. Chains B and C are colored red and blue, respectively. The N-terminal tag residues (chain B) are colored gray. (D) Schematic representation of the hexameric ring structure of TTHA0727. Chains A, B, and C are colored green, red, and blue, respectively. Chains A’, B’, and C’, which are related to chains A, B, and C by the crystallographic twofold symmetry axis, are colored yellow, magenta, and cyan, respectively. The arrow represents the crystallographic twofold symmetry axis. (E) Electrostatic surface representation of the TTHA0727 hexamer. Red and blue surfaces represent negative and positive potentials (–10 kBT−1 to 10 kBT−1), respectively. The electrostatic surface potentials were calculated using the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver (APBS) (Baker et al. 2001) with the PyMOL APBS tools.

Results and Discussion

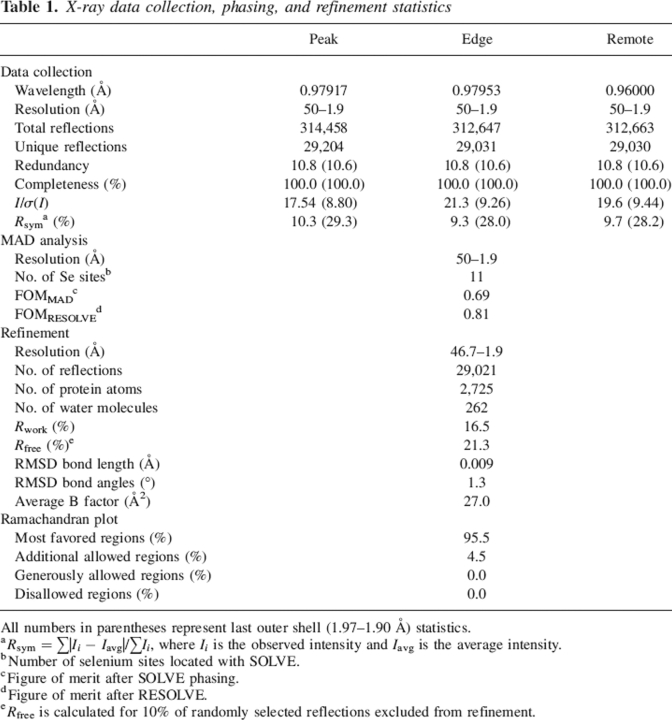

The TTHA0727 crystal belongs to the trigonal space group P3121, with unit cell constants of a = b = 107.102 Å, c = 55.455 Å. The structure was refined to 1.9 Å by the MAD method. The crystallographic data are summarized in Table 1. The final model includes 364 amino acid residues of three TTHA0727 monomers and 262 water molecules per asymmetric unit. Since there were additional electron densities in chains A and B, the extra nine residues of the N-terminal tag were also modeled. In chain C, five residues at the N terminus of TTHA0727 could not be identified in the electron density, due to disorder.

Table 1.

X-ray data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics

All numbers in parentheses represent last outer shell (1.97–1.90 Å) statistics.

a Rsym = ∑|Ii − Iavg|/∑Ii, where Ii is the observed intensity and Iavg is the average intensity.

b Number of selenium sites located with SOLVE.

c Figure of merit after SOLVE phasing.

d Figure of merit after RESOLVE.

e Rfree is calculated for 10% of randomly selected reflections excluded from refinement.

The TTHA0727 monomer structure consists of seven α-helices (α1–α7) and one short 310-helix (η1) (Fig. 1A,B). The extra residues of the N-terminal tag in chains A and B bound to the cleft between α1 and α3. There are three protein chains per asymmetric unit, and the structures of the three chains are essentially identical, with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of only 0.25 Å for the Cα atoms. Chains B (red) and C (blue) form a tight homodimer through interactions between the α-helices (α2–α7) intertwined with each other (Fig. 1C). The two chains (A and A′) also dimerize by the crystallographic twofold symmetry axis, similar to the dimerization of chains B and C. Moreover, the six chains of the two asymmetric units were multimerized by the crystallographic twofold symmetry axis, suggesting that TTHA0727 forms a homohexameric ring structure composed of three dimers, through interactions between each region of α5–α7 (Fig. 1D). There is a small tunnel in the center of the hexameric ring. According to the analytical ultracentrifugation (Supplemental Material), the molecular mass of TTHA0727 was ∼86.8 kDa, indicating that TTHA0727 exists as a hexamer in solution, since the molecular mass of the TTHA0727 monomer with the N-terminal tag is 14.7 kDa. The electrostatic potential distribution on the solvent-accessible surface of the TTHA0727 hexamer is shown in Figure 1E. There is a relatively large positively charged region on the side of the ring structure, suggesting the possibility of an interaction with some negatively charged molecules.

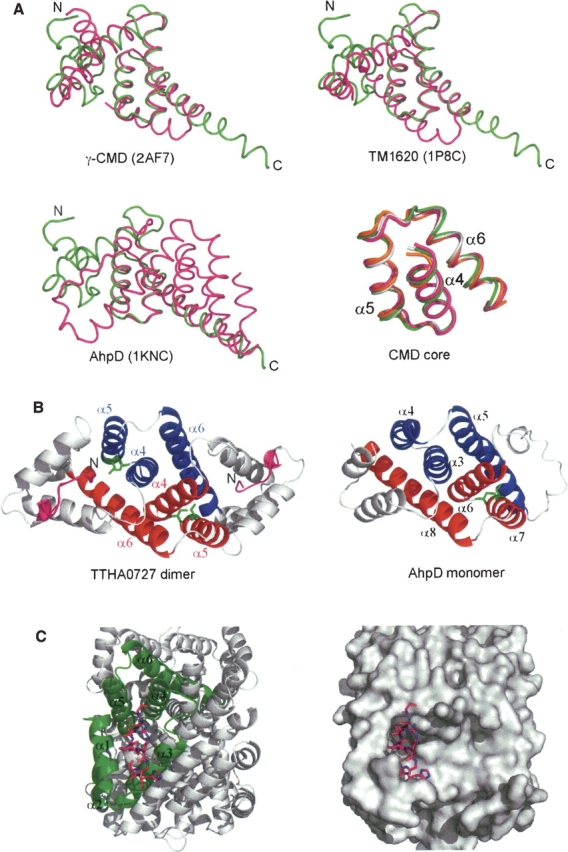

A DALI (Holm and Sander 1993) structural homology search showed that TTHA0727 resembles γ-CMD from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (PDB ID: 2AF7, Z-score = 8.0, RMSD = 2.9 Å over 91 Cα atoms, sequence identity = 18%), the conserved hypothetical protein TM1620 from Thermotoga maritima (PDB ID: 1P8C, Z-score = 6.6, RMSD = 0.8 Å over 51 Cα atoms, sequence identity = 17%), and AhpD from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Bryk et al. 2002; Nunn et al. 2002) (PDB ID: 1KNC, Z-score = 6.1, RMSD = 2.8 Å over 87 Cα atoms, sequence identity = 14%) (Fig. 2A), although the sequence identities are relatively low. The superimposition of the main-chain structures of the TTHA0727 monomer and its homologs revealed that the structures of the three α-helices (α4–α6 in TTHA0727) are remarkably conserved, although the other parts do not overlap well, suggesting that the three α-helices compose the common structural motif (CMD core) for the CMD family proteins (Fig. 2A). The three α-helices are involved in the formation of the structural core region and their stable multimerization. The γ-CMD from M. thermoautotrophicum and TM1620 from T. maritima form homohexamers in the crystal, similar to those of TTHA0727, and the CMD core regions also overlap well in the hexamers. On the other hand, AhpD from M. tuberculosis forms a homotrimer. The structural comparison of the TTHA0727 dimer and the AhpD monomer suggested the structural duplication of the CMD core motif in AhpD (Fig. 2B), and consequently the trimer of AhpD corresponds to the hexamer of TTHA0727.

Figure 2.

(A) Superimposition of the main-chain structures of the TTHA0727 monomer (green) and its structural homologs (magenta). The lower right panel represents the common structural core motif for the CMD family proteins (CMD core), which is the superimposition of three α-helices (α4–α6) of TTHA0727 and its structural homologs. TTHA0727, γ-CMD (PDB ID: 2AF7), TM1620 (1P8C), and AhpD (1KNC) are colored green, magenta, gray, and orange, respectively. All superimpositions were carried out with lsqkab (Kabsch 1976). (B) Comparison of the structures of the TTHA0727 dimer and the AhpD monomer. The N-terminal tag residues of TTHA0727 are colored magenta. The helices that correspond to α4–α6 of chains A and A′ of TTHA0727 are colored red and blue, respectively. The active site residues Cys 130 and Cys 133 of AhpD, and the corresponding residues Ser 70 and Cys 73 of TTHA0727 (chain A), are denoted by green sticks. (C) Ribbon representation and surface representation of the cleft region of TTHA0727. The N-terminal tag residues (chain A) are denoted by magenta sticks.

In addition, the region (Ser 70, Cys 73) of TTHA0727 corresponding to the active site region (Cys 130, Cys 133) of AhpD is located at the bottom of the cleft in TTHA0727. In chains A and B of TTHA0727, the binding of the N-terminal extra residues to the cleft region suggests that this region is the putative binding/active site for some small molecules, assuming that the extra residues form a ligand-like molecule (Fig. 2C).

These results imply that the CMD family proteins have evolved into various functional proteins, while they retained the hexameric or trimeric ring structure with the common structural framework (CMD core). The present structural study of TTHA0727, a distinct member from γ-CMD and AhpD, will contribute to the further analyses of TTHA0727 and the CMD family proteins.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

The gene encoding TTHA0727 (TT1628) from T. thermophilus HB8 was cloned into the plasmid vector pHCEH as a fusion with an N-terminal His-tag. The selenomethionine (SeMet)-substituted TTHA0727 protein was expressed in Escherichia coli B834 (DE3). The E. coli lysate was heated for 30 min at 70°C, and the proteins were purified by a series of HisTrap HP, HiTrap SP HP, RESOURCE S, and HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 pg column chromatography steps (GE Healthcare). The yield of the purified TTHA0727 protein was 2.3 mg/1 g wet cells.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystals of TTHA0727 (SeMet) were grown at 20°C by using the sitting drop vapor-diffusion method. Small, irregular crystals were produced in 21%–22% PEG 3350 and 0.1 M potassium formate (Hampton Research). These crystals were then used for microseeding of sitting drops equilibrated against a reservoir solution containing 21% PEG 3350 and 0.1 M potassium formate. Crystals with a rod-like morphology (∼200 × 150 × 50 μm3) were obtained within 2 wk, and were used for data collection.

The data collection was carried out at 100 K with a mixture of equal parts of Paratone-N and paraffin oil (Hampton Research) as a cryoprotectant. The MAD data were collected at three different wavelengths at BL26B1 (Yamamoto et al. 2002), SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan), and were recorded on a Jupiter 210 CCD detector (Rigaku). All diffraction data were processed with the HKL2000 program (Otwinowski and Minor 1997).

Structure determination and refinement

The program SOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen 1999) was used to locate the selenium sites and to calculate the phases, and RESOLVE (Terwilliger 2002) was used for the density modification and partial model building. The rest of the model was built with the program O (Jones et al. 1991) and was refined with the program Crystallography & NMR system (CNS) (Brünger et al. 1998). Refinement statistics are presented in Table 1. The quality of the model was inspected by the program PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993). The graphic figures were created using the program PyMOL (DeLano Scientific). The atomic coordinates and the structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with the accession code 2CWQ.

Electronic supplemental material

The result of the analytical ultracentrifugation is shown in the electronic supplemental material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Yamamoto for data collection at the RIKEN Structural Genomics beamline, Dr. M. Kukimoto-Niino for helpful advice about structural analysis, Mr. S. Kamo for computer maintenance, and Ms. A. Ishii, Ms. K. Yajima, Ms. M. Sunada, and Ms. T. Nakayama for clerical assistance. This work was supported by the RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative (RSGI), the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: Shigeyuki Yokoyama, Protein Research Group, Genomic Sciences Center, RIKEN Yokohama Institute, 1-7-22, Suehiro-cho, Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan; e-mail: yokoyama@biochem.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp; fax: 81-45-503-9195.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062148506.

References

- Baker N.A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M.J., McCammon J.A. 2001. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 10037–10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T., Adams P.D., Clore G.M., DeLano W.L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Jiang J.S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N.S.et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination Acta Crystallogr. D54: 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk R., Lima C.D., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Nathan C. 2002. Metabolic enzymes of mycobacteria linked to antioxidant defense by a thioredoxin-like protein Science 295: 1073–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D.I., Metoz F. 1999. ESPript: Analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript Bioinformatics 15: 305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson W.A. 1991. Determination of macromolecular structures from anomalous diffraction of synchrotron radiation Science 254: 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henne A., Bruggemann H., Raasch C., Wiezer A., Hartsch T., Liesegang H., Johann A., Lienard T., Gohl O., Martinez-Arias R.et al. 2004. The genome sequence of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus Nat. Biotechnol. 22: 547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. and Sander C. 1993. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices J. Mol. Biol. 233: 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou J.Y., Cowan S.W., Kjeldgaard M. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models Acta Crystallogr. A47: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. 1976. Solution for best rotation to relate 2 sets of vectors Acta Crystallogr. A32: 922–923. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. and Sander C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features Biopolymers 22: 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk H.P., Clayton R.A., Tomb J.F., White O., Nelson K.E., Ketchum K.A., Dodson R.J., Gwinn M., Hickey E.K., Peterson J.D.et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus Nature 390: 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., Macarthur M.W., Moss D.S., Thornton J.M. 1993. Procheck - a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26: 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn C.M., Djordjevic S., Hillas P.J., Nishida C.R., Ortiz de Montellano P.R. 2002. The crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alkylhydroperoxidase AhpD, a potential target for antitubercular drug design J. Biol. Chem. 277: 20033–20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode Methods Enzymol. 276: 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanier R.Y. and Ornston L.N. 1973. The β-ketoadipate pathway Adv. Microb. Physiol. 9: 89–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. 2002. Automated structure solution, density modification and model building Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58: 1937–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. and Berendzen J. 1999. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55: 849–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., Ueno G., Ida K., Kanda H., Miyano M., Ishikawa T. 2002. RIKEN structural genomics beamlines at SPring-8 Acta Crystallogr. A58: C302. [Google Scholar]