Abstract

Peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) are pattern recognition receptors of the innate immune system that bind bacterial peptidoglycans (PGNs). We determined the crystal structure, to 2.1 Å resolution, of the C-terminal PGN-binding domain of human PGRP-Iα in complex with a muramyl pentapeptide (MPP) from Gram-positive bacteria containing a complete peptide stem (L-Ala-D-isoGln-L-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala). The structure reveals important features not observed previously in the complex between PGRP-Iα and a muramyl tripeptide lacking D-Ala at stem positions 4 and 5. Most notable are ligand-induced structural rearrangements in the PGN-binding site that are essential for entry of the C-terminal portion of the peptide stem and for locking MPP in the binding groove. We propose that similar structural rearrangements to accommodate the PGN stem likely characterize many PGRPs, both mammalian and insect.

Keywords: bacteria, crystal structure, innate immunity, peptidoglycan, PGRP

The innate immune system constitutes the first line of defense against invading microorganisms in both vertebrates and invertebrates (Medzhitov and Janeway 2002; Hoffmann 2003). It recognizes microbes by means of conserved pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that bind unique products of microbial metabolism (pathogen-associated molecular patterns, or PAMPs). Examples of PAMPs recognized by PRRs such as Toll receptors, peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs), and NOD proteins include lipopolysaccharide, flagellin, nonmethylated CpG sequences, and peptidoglycan (PGN) (Medzhitov and Janeway 2002; Hoffmann 2003).

PGRPs, which are highly conserved from insects to mammals, are important contributors to host defense against microbial infections (Hoffmann 2003; Dziarski 2004). These PRRs, of which >40 have been identified, bind PGN from both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. In addition, individual PGRPs display distinct specificities for PGNs from different microbes (Swaminathan et al. 2006). PGNs are polymers of alternating N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) in β(1 → 4) linkage, cross-linked by short peptide stems composed of alternating L- and D-amino acids (Fig. 1A) (Doyle and Dziarski 2001). Whereas the carbohydrate backbone is preserved in all bacteria, considerable diversity exists in the peptide moiety. According to the residue at position 3 of the stems, PGNs are classified into two major groups: L-lysine-type (Lys-type) and meso-diaminopimelic acid-type (Dap-type). Dap-type PGN peptides are usually directly cross-linked, whereas Lys-type PGN peptides are interconnected by a peptide bridge that varies in length and amino acid composition in different bacteria (Fig. 1A).

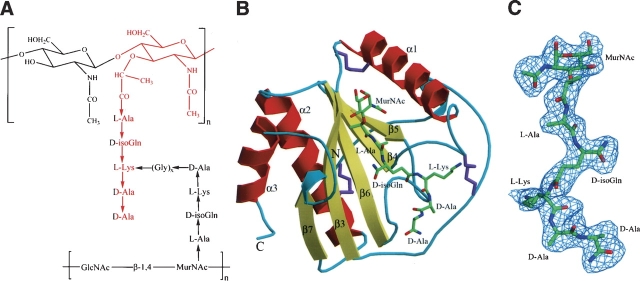

Figure 1.

Structure of PGNs and the PGRP-Iα–MPP complex. (A) Schematic representation of Lys-type PGNs and MPP. The fragment highlighted in red corresponds to the MPP ligand used to form the PGRP-IαC–MPP complex. (B) The PGRP-IαC–MPP complex (complex A). (Red) Helices; (yellow) strands; (cyan) coils. The N and C termini are indicated. The bound MPP is drawn in stick representation: (green) carbon atoms; (blue) nitrogen atoms; (red) oxygen atoms. The three disulfide bonds are purple. Secondary structure elements are labeled following the numbering for unbound PGRP-IαC (Guan et al. 2004a). (C) σA-weighted Fo – Fc omit map for the MPP ligand in complex A. The contour level is 2σ.

Drosophila PGRPs activate two distinct signaling pathways that induce production of anti-microbial peptides: the Toll receptor pathway, which is triggered by Lys-type PGNs from Gram-positive bacteria, and the Imd pathway, which is activated by Dap-type PGNs from Gram-negative bacteria (Hoffmann 2003). Mammalian PGRPs, located in neutrophil and eosinophil granules, participate in the intra- and extracellular killing of both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria (Dziarski 2004; Cho et al. 2005).

To date, crystal structures of five PGRPs in unliganded form have been determined: Drosophila PGRP-LB (Kim et al. 2003), PGRP-SA (Chang et al. 2004; Reiser et al. 2004), and PGRP-LCa (Chang et al. 2005), human PGRP-S (Guan et al. 2005), and the C-terminal PGN-binding domain of human PGRP-Iα (designated PGRP-IαC) (Guan et al. 2004a). All possess a conserved L-shaped groove for PGN binding, except that in PGRP-LCa this groove is constricted due to two helical insertions that appear to abolish PGN binding. In addition, we recently reported the structure of PGRP-IαC in complex with MurNAc-L-Ala-D-isoGln-L-Lys, a muramyl tripeptide (MTP) representing the core of Lys-type PGN (Guan et al. 2004b). The complex revealed that the tripeptide stem is buried at the deep end of the binding groove, with MurNAc situated in the middle. No significant conformational changes are associated with complex formation. However, the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex was obtained not by cocrystallization, but by soaking preformed crystals of the free protein in solutions of the ligand, such that lattice contacts could prevent the receptor from adopting other conformations. Furthermore, MTP lacks D-Ala at peptide position 4, which is present in PGNs from all bacteria, as well as D-Ala at position 5, which occurs in some species (Fig. 1A). To obtain a more complete picture of PGRP–PGN interactions, we cocrystallized PGRP-IαC with MurNAc-L-Ala-D-isoGln-L-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala, a muramyl pentapeptide (MPP) containing a complete peptide stem that binds PGRP-IαC much more tightly than MTP (Kumar et al. 2005). This structure, while confirming basic elements of the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex, reveals important new features, including ligand-induced conformational changes in the PGN-binding groove that probably occur in many PGRPs.

Results and Discussion

Overview of the complex structure

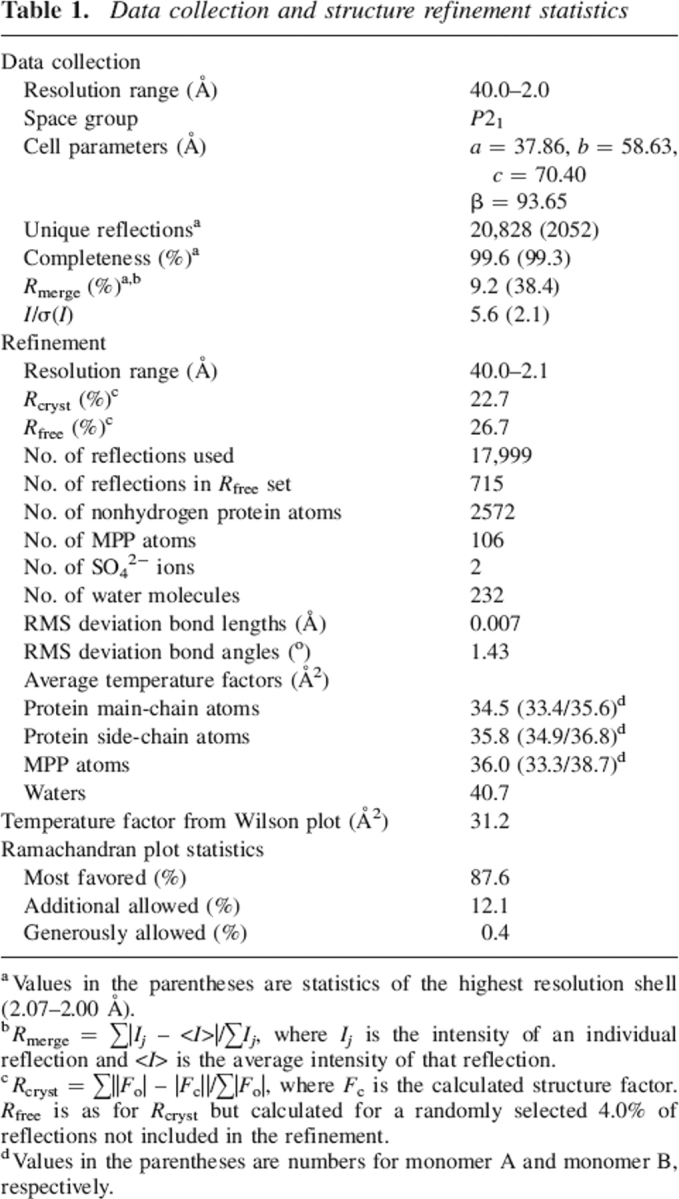

The structure of the cocrystallized PGRP-IαC–MPP complex was determined by molecular replacement to 2.1 Å resolution (Table 1). The crystal contains two complex molecules (designated A and B) in the asymmetric unit. Superposition of the two complexes gave a root-mean-square (RMS) difference of 0.21 Å for 165 α-carbon atoms, indicating close similarity.

Table 1.

Data collection and structure refinement statistics

a Values in the parentheses are statistics of the highest resolution shell (2.07–2.00 Å).

b Rmerge = ∑|Ij – <I>|/∑Ij, where Ij is the intensity of an individual reflection and <I> is the average intensity of that reflection.

c Rcryst = ∑||Fo| – |Fc||/∑|Fo|, where Fc is the calculated structure factor. Rfree is as for Rcryst but calculated for a randomly selected 4.0% of reflections not included in the refinement.

d Values in the parentheses are numbers for monomer A and monomer B, respectively.

PGRP-IαC comprises a central β-sheet composed of five β-strands—four parallel and one (β5) antiparallel—and three α-helices (Fig. 1B). The PGN-binding site resides in a long cleft whose walls are formed by helix α1 and five loops (β3–α1, α1–β4, β5–β6, β6–α2, and β7–α3) that extend above the β-sheet platform. For both PGRP-IαC–MPP complexes in the asymmetric unit, unambiguous electron density corresponding to the entire MPP molecule was visible in 2Fo – Fc and Fo – Fc omit maps (Fig. 1C). The occupancy of MPP in each complex is 1.0, with average temperature factors (B) of 33 Å2 (complex A) and 39 Å2 (complex B), comparable to the average B values of main-chain atoms of PGRP-IαC in the two complexes (33 Å2 and 36 Å2, respectively).

Interactions in the PGN-binding site

The MPP ligand makes nearly identical interactions with PGRP-IαC in complexes A and B, excluding several minor differences attributable to crystal packing. Accordingly, the following description of PGRP–PGN interactions applies to both complexes.

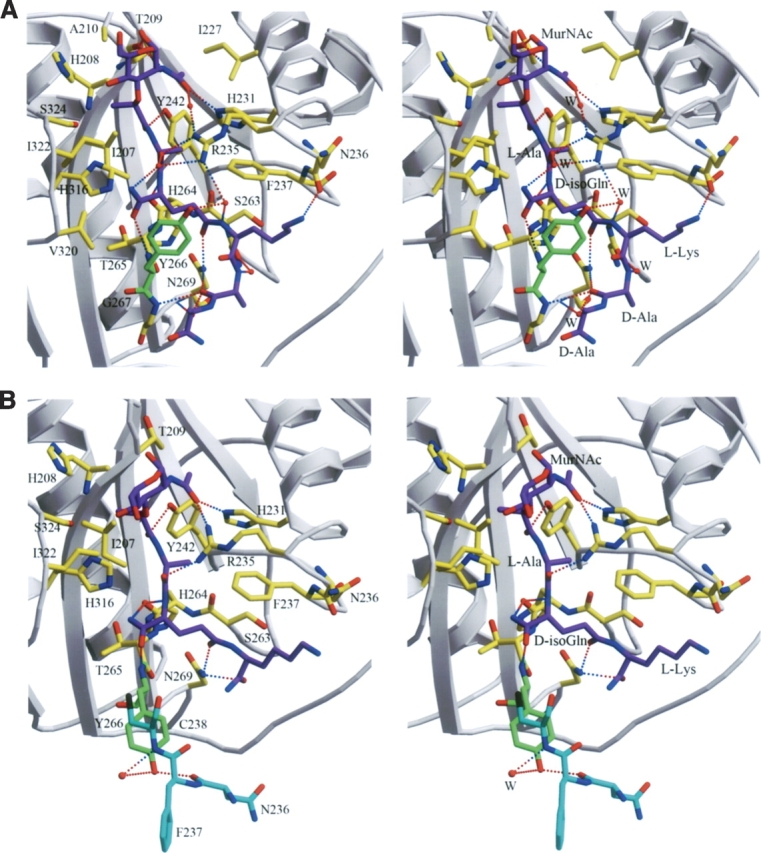

The PGN-binding cleft of human PGRP-IαC, whose general topology is maintained in other PGRPs, is ∼24 Å long, with a shallow (6–7 Å) end, flanked by helix α1 and loops β3–α1 and β6–α2, and a deep (12–13 Å) end, flanked by loops α1–β4, β5–β6, and β7–α3. As in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Guan et al. 2004b), the pentapeptide stem of MPP (L-Ala-D-isoGln-L-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala) is held in an extended conformation at the deep end of the binding groove, while the MurNAc moiety lies in a pocket in the middle of the groove, with its pyranose ring perpendicular to the floor of the pocket (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Intermolecular contacts in the PGRP-IαC–MPP complex. (A) Stereo view of interactions between PGRP-IαC and MPP at the PGN-binding site in complex A. (Purple) MPP; (gray) PGRP-IαC; (green) Tyr266; (yellow) other MPP-contacting residues. Hydrogen bonds are drawn as dashed lines; residues forming van der Waals contacts with MPP are also highlighted. Bound waters (W) mediating hydrogen bonds between PGRP and MPP are shown as red balls. (B) Stereo view of interactions between PGRP-IαC and MTP in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Guan et al. 2004b). Shown in cyan are residues from a neighboring complex in the crystal that form lattice contacts, preventing the Tyr266 side chain (green) from adopting the conformation found in the cocrystallized PGRP-IαC–MPP complex.

The PGRP-IαC–MPP complex buries a total solvent-accessible surface of 1192 Å2, of which 504 Å2 is contributed by PGRP-IαC and 688 Å2 by MPP, as calculated with program Areaimol in CCP4 suite (CCP4 1994). The interfaces with MurNAc and the pentapeptide stem account for 36% and 64%, respectively, of the total buried surface. MPP is 60% buried in the PGN-binding site, with its glycan and peptide portions buried to similar degrees. The PGRP-IαC–MPP interface is predominantly hydrophilic and includes 12 bound water molecules, of which two are completely inaccessible to bulk solvent. Five of the interfacial waters mediate hydrogen bonds between PGRP-IαC and MPP (Fig. 2A). By contrast, no interfacial waters or water-mediated hydrogen bonds were observed in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Fig. 2B), despite comparable resolution (2.3 Å).

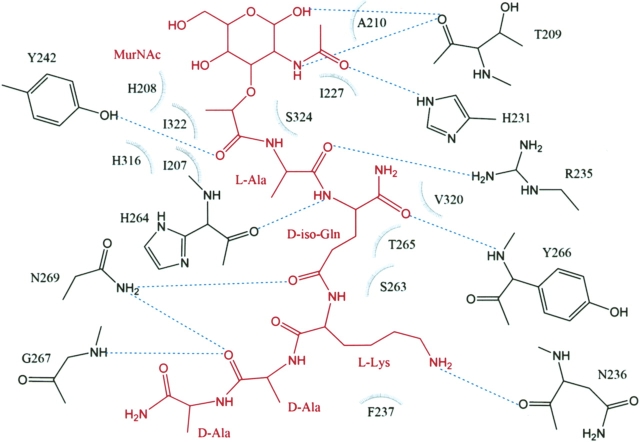

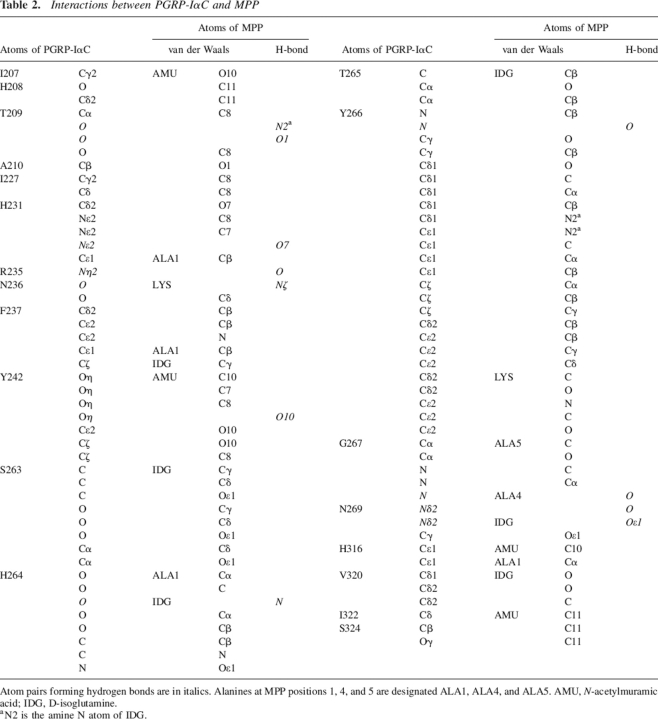

MPP makes extensive interactions with 20 residues lining the PGN-binding cleft of PGRP-IαC (Fig. 3), including 11 hydrogen bonds and 79 van der Waals contacts (Table 2). In the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex, by comparison, MTP forms nine hydrogen bonds and 43 van der Waals contacts with 16 PGRP-IαC residues. Most of the interactions with MPP (seven of 11 direct hydrogen bonds, four of five water-mediated hydrogen bonds, and 58 of 79 van der Waals contacts) are with the peptide, rather than the glycan, portion of the PGN analog. The MurNAc moiety forms four hydrogen bonds with the side chains of three PGRP-IαC residues (Fig. 3). Most (five of seven) of the hydrogen bonds to the pentapeptide stem of MPP involve main-chain atoms of the peptide. L-Ala1 only forms an H-bond with PGRP-IαC, while D-isoGln contributes three H-bonds in MPP–PGRP-IαC interactions, two through its main-chain atoms N and Oɛ1, and another through atom O (Fig. 3). The side chain of L-Lys3 in MPP packs against Asn236 and Phe237, forming an H-bond through its atom Nζ with main-chain atom O of Asn236 (Table 2). Residue D-Ala4 of MPP, which is absent in MTP, engages PGRP-IαC through both direct (D-Ala4 O–Gly267 N and D-Ala4 O–Asn269 Nδ2) and solvent-mediated (D-Ala4 O–H20–Asn269 N) hydrogen bonds, while D-Ala5 makes only a few van der Waals contacts with Gly267 (Table 2). This suggests that D-Ala4 contributes more than D-Ala5 to PGN binding by PGRPs, consistent with the fact that all bacterial PGNs contain D-Ala4, whereas D-Ala5 is missing in many species (Fig. 1A). The functional importance of a complete peptide stem is underscored by the substantially higher affinity of PGRP-IαC for MPP than MTP (Kumar et al. 2005).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the interactions between PGRP-IαC and MPP. MPP is red; hydrogen bonds are drawn as blue dashed lines. Residues making van der Waals contacts with MPP are indicated by arcs with spokes radiating toward the ligand moieties they contact. Water-mediated interactions between PGRP-IαC and MPP are omitted for clarity.

Table 2.

Interactions between PGRP-IαC and MPP

Atom pairs forming hydrogen bonds are in italics. Alanines at MPP positions 1, 4, and 5 are designated ALA1, ALA4, and ALA5. AMU, N-acetylmuramic acid; IDG, D-isoglutamine.

a N2 is the amine N atom of IDG.

There are some other differences in PGRP–ligand interactions between the cocrystallized PGRP-IαC–MPP and soaked PGRP-IαC–MTP complexes, besides those mentioned above. Among the 20 MPP-contacting residues, Tyr266 makes by far the greatest number of van der Waals contacts (24 of 79) with D-isoGln2 and L-Lys3 (Table 2), due to the movement of the side chain in Tyr266 upon binding MPP (see below). In contrast, Tyr266 makes only two contacts with ligand in the PGRP-IαC–MTP. Furthermore, Thr209 forms two main-chain hydrogen bonds with MurNAc in the PGRP-IαC–MPP complex, but none in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Fig. 2). Similarly, whereas Asn236 makes only van der Waals contacts with L-Lys3 of MTP, it also makes a hydrogen bond with L-Lys3 of MPP. These additional interactions may, along with the longer peptide stem, contribute to the higher affinity of MPP than MTP (Kumar et al. 2005).

Ligand-induced structural rearrangement in PGRP-IαC

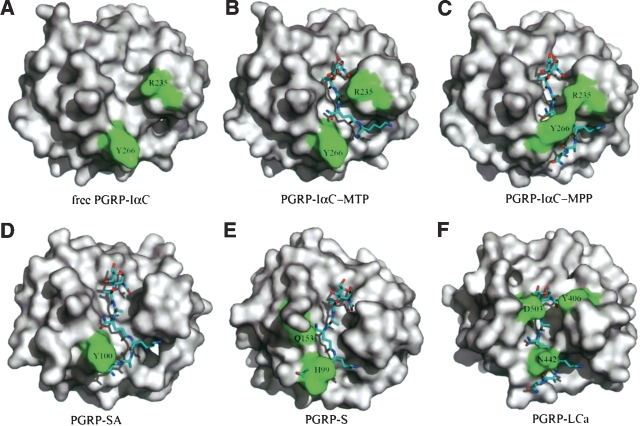

Superposition of free (Guan et al. 2004a) and MPP-bound PGRP-IαC structures gave RMS differences in α-carbon positions of 0.43 Å and 0.47 Å, respectively, for complexes A and B, indicating no substantial changes in main-chain conformation upon ligand binding. However, detailed examination of the PGN-binding groove revealed several side-chain rearrangements, not observed in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex, that contribute to MPP recognition (Fig. 2). Most notably, the side chain of Tyr266 undergoes an ∼110° rotation from its position in free (Fig. 4A) or MTP-bound PGRP-IαC (Fig. 4B), thereby acting as a flap to “lock” MPP in the binding groove (Fig. 4C). This same movement, which introduces extensive contacts with D-isoGln2 and L-Lys3 not found in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Table 2), is observed for both PGRP-IαC–MPP complexes in the asymmetric unit. The difference between PGRP-IαC–MPP and PGRP-IαC–MTP structures can be explained by lattice contacts in the PGRP-IαC–MTP crystal that prevent the Tyr266 side chain from adopting an alternate rotamer position (Fig. 2B). That the conformation of Tyr266 in the PGRP-IαC–MTP complex probably represents the ground state for this residue is supported by a second crystal form of free PGRP-IαC (Guan et al. 2004a), where Tyr266 displays a nearly identical conformation, despite a very different crystallographic environment that imposes no obvious restrictions on side-chain rotation. Repositioning of the Tyr266 side chain is also crucial for MPP binding in order to avoid steric clashes with D-Ala4 and D-Ala5 (this likely explains our inability to soak MPP into preformed PGRP-IαC crystals). Moreover, the shift in Tyr266 allows D-Ala4 and D-Ala5 to interact with Gly267 (Table 2), as this residue is completely masked by the bulky Tyr266 side chain in unliganded PGRP-IαC.

Figure 4.

Ligand-induced conformational changes in PGRPs. (A) Molecular surface of human PGRP-IαC in free form (Guan et al. 2004a). The view is looking down onto the PGN-binding groove; the protein is oriented as in Figure 2. Arg235 and Tyr266 are highlighted in green. (B) The PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Guan et al. 2004b). The PGN analog MTP is shown in stick representation. (C) The PGRP-IαC–MPP complex. (D) Drosophila PGRP-SA (Reiser et al. 2004) with MPP docked into the binding site by superposing the PGRP-IαC–MPP structure. Tyr100 (green) of PGRP-SA, which corresponds to Tyr266 of PGRP-IαC, is predicted to collide with D-Ala4 and D-Ala5 of MPP. (E) Human PGRP-S (Guan et al. 2005) with MPP docked into the binding groove by superposing the PGRP-IαC–MPP complex. Steric clashes are expected between His99 and D-Ala4 and D-Ala5, as well as between Gln153 and D-isoGln2. (F) Drosophila PGRP-LCa (Chang et al. 2005) with MPP docked into the binding groove by superposing the PGRP-IαC–MPP complex. Two major residues, Asn442 and Asp503, and one minor residue Y406, would provide a barricade for ligand binding.

Implications for PGN binding by other PGRPs

The crystal structure of human PGRP-IαC in complex with MPP, a PGN derivative containing a complete peptide stem, provides insight into ligand-induced structural rearrangements in PGRPs upon binding PGN, which was not observed in the previous PGRP-IαC–MTP complex (Guan et al. 2004b). We asked whether other PGRPs might undergo similar conformation changes upon binding PGN. Like human PGRP-IαC, Drosophila PGRP-SA and human PGRP-S recognize Lys-type PGNs from Gram-positive bacteria (Hoffmann 2003; Cho et al. 2005; Kumar et al. 2005). As only unliganded structures are available for PGRP-SA and PGRP-S (Chang et al. 2004; Reiser et al. 2004; Guan et al. 2005), we docked MPP into their respective PGN-binding grooves by superposing the PGRP-IαC–MPP complex. In the docked PGRP-SA–MPP complex (Fig. 4D), D-Ala4 and D-Ala5 are predicted to clash with Tyr100, which corresponds to Tyr266 of PGRP-IαC (Fig. 4A). However, this clash would be relieved by rotating the Tyr100 side chain to the position occupied by the Tyr266 side chain in the PGRP-IαC–MPP structure (Fig. 4C), permitting PGRP-SA to bind PGN. Likewise, in the docked PGRP-S–MPP structure (Fig. 4E), the side chain of His99 collides with D-Ala4 and D-Ala5 of MPP. We also docked MPP into the PGN binding groove of Drosophila PGRP-LCa (10) (Fig. 4F), as we recently determined by ITC that PGRP-LCa binds to MPP (Swaminathan et al. 2006). Two residues, Asp503 and Asn442, were found to clash with the MurNAc moiety and the peptide stem, respectively, such that ligand engagement would require conformational change. Taken together, therefore, it appears that structural rearrangement in the PGN binding groove to accommodate the ligand is not a particular case in human PGRP-Iα but may be characteristic of many PGRPs, including mammalian and insect ones. Our results further suggest that entry of the peptide stem of MPP into the PGN-binding cleft of PGRP-IαC involves engagement of the N-terminal portion of the stem (L-Ala-D-isoGln-L-Lys) and, concomitantly, ligand-induced rearrangement in the receptor that permits the C-terminal portion (D-Ala-D-Ala) to enter, and help lock MPP in the binding site.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Procedures for expressing and purifying human PGRP-IαC have been reported (Guan et al. 2004a). The PGN analog MPP was synthesized as described (Swaminathan et al. 2006).

Crystallization and data collection

The PGRP-IαC–MPP complex was crystallized at room temperature in hanging drops by mixing 1.5 μL of a solution containing PGRP-IαC (6 mg/mL) and MPP (2 mg/mL) with 1 μL of reservoir solution containing 15% PEG-MME 2000, 15 mM NiSO4, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Crystals were flash-cooled in a nitrogen stream without additional cryoprotection. X-ray diffraction data to 2.0 Å resolution were recorded in-house at 100 K using an R-axis IV++ image plate detector. The data were processed and scaled using CrystalClear (Pflugrath 1999) (Table 1). The crystal contains two molecules in the asymmetric unit.

Structure determination and refinement

The structure was solved by molecular replacement with AMoRe (Navaza 1994), using as a search probe free PGRP-IαC (PDB accession code 1SK3). The translation function search gave a clear solution for the first molecule, with a correlation coefficient of 0.343 and Rfactor of 49.9% at 8.0–3.5 Å. This solution was fixed to search for the second molecule, yielding a correlation coefficient of 0.675 and Rfactor of 36.0%. Refinement was carried out with CNS 1.1 (Brünger et al. 1998) using data in the 40.0–2.1 Å resolution range, and model building was done with XtalView (McRee 1999). Rigid body refinement, followed by energy minimization, resulted in Rfactor and Rfree values of 33.9% and 34.9%, respectively. Continuous positive density could be observed in the PGN-binding cleft of each monomer in both 2Fo – Fc and Fo – Fc electron density maps. Based on the Fo – Fc map, MPP was built manually into the two PGRP-IαC monomers; σA-weighted Fo – Fc maps were calculated for further model adjustment. After minimization, Rcryst was reduced to 32.2% and Rfree to 32.8%. Group and individual B refinements were carried out, and water molecules were added to the final model, which comprises residues 177–341 and one MPP per monomer, two sulfates, and 231 waters. The final Rcryst is 22.6% and Rfree is 26.7% for all data between 40.0 and 2.1 Å (Table 1). Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited under PDB accession code 2APH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants to G.-J.B. and R.A.M.

Footnotes

Reprint requests to: Roy A. Mariuzza, Center for Advanced Research in Biotechnology, W.M. Keck Laboratory for Structural Biology, University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, Rockville, MD 20850, USA; e-mail: mariuzza@carb.nist.gov; fax: (240) 314-6255.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.062077606.

Abbreviations: PGRP, peptidoglycan recognition proteins; PGN, peptidoglycans; MPP, muramyl pentapeptide; Dap, meso-diaminopimelic acid; MurNAc, muramyl acid; PGRP-IαC, the C-terminal PGN-binding domain of human PGRP-Iα; MTP, muramyl tripeptide

References

- Brünger A.T., Adams P.D., Clore G.M., DeLano W.L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Jiang J.S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N.S.et al. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54: 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.I., Pili-Floury S., Herve M., Parquet C., Chelliah Y., Lemaitre B., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Deisenhofer J. 2004. A Drosophila pattern recognition receptor contains a peptidoglycan docking groove and unusual L, D-carboxypeptidase activity PLoS Biol. 2: 1293–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.I., Ihara K., Chelliah Y., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Wakasuki S., Deisenhofer J. 2005. Structure of the ectodomain of Drosophila peptidoglycan recognition protein LCa suggests a molecular mechanism of pattern recognition Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102: 10279–10284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J.H., Fraser I.P., Fukase K., Kusumoto S., Fujimoto Y., Stahl G.L., Ezekowitz R.A.B. 2005. Human peptidoglycan recognition protein-S is an effector of neutrophil-mediated innate immunity Blood 106: 2551–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (CCP4). 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50: 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle R.J. and Dziarski R. 2001. The bacterial cell: Peptidoglycan In Molecular medical microbiology (ed. Sussman M.) . pp. 137–153. Academic Press, London UK.

- Dziarski R. 2004. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) Mol. Immunol. 40: 877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan R., Malchiodi E.L., Wang Q., Schuck P., Mariuzza R.A. 2004a. Crystal structure of the C-terminal peptidoglycan-binding domain of human peptidoglycan recognition protein Iα J. Biol. Chem. 279: 31873–31882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan R., Roychowdhury A., Ember B., Kumar S., Boons G.-J., Mariuzza R.A. 2004b. Structural basis for peptidoglycan binding by peptidoglycan recognition proteins Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101: 17168–17173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan R., Wang Q., Sundberg E.J., Mariuzza R.A. 2005. Crystal structure of human peptidoglycan recognition protein S (PGRP-S) at 1.7 Å resolution J. Mol. Biol. 347: 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J.A. 2003. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature 426: 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.S., Byun M., Oh B.H. 2003. Crystal structure of peptidoglycan recognition protein LB from Drosophila melanogaster Nat. Immunol. 4: 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Roychowdhury A., Ember B., Wang Q., Guan R., Mariuzza R.A., Boons G.J. 2005. Selective recognition of synthetic Gram-positive and negative peptidoglycan fragments by human PGRP-S and PGRP-Iα J. Biol. Chem. 280: 37005–37012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee D.E. 1999. XtalView/Xfit. A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density J. Struct. Biol. 125: 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. and Janeway Jr. C.A. 2002. Decoding patterns of self and nonself by the innate immune system Science 296: 298–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaza J. 1994. AMoRe: An automated package for molecular replacement Acta Crystallogr. A 50: 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pflugrath J.W. 1999. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55: 1718–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser J.B., Teyton L., Wilson I.A. 2004. Crystal structure of the Drosophila peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP)-SA at 1.56 Å resolution J. Mol. Biol. 340: 909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan C.P., Brown P., Roychowdhury A., Wang Q., Guan R., Silverman N., Goldman W., Boons G.-J., Mariuzza R.A. 2006. Dual strategies for peptidoglycan discrimination by peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103: 684–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]