Abstract

We present the Coordinate Internal Representation of Solvation Energy (CIRSE) for computing the solvation energy of protein configurations in terms of pairwise interactions between their atoms with analytic derivatives. Currently, CIRSE is trained to a Poisson/surface-area benchmark, but CIRSE is not meant to fit this benchmark exclusively. CIRSE predicts the overall solvation energy of protein structures from 331 NMR ensembles with 0.951 ± 0.047 correlation and predicts relative solvation energy changes between members of individual ensembles with an accuracy of 15.8 ± 9.6 kcal/mol. The energy of individual atoms in any of CIRSE's 17 types is predicted with at least 0.98 correlation. We apply the model in energy minimization, rotamer optimization, protein design, and protein docking applications. The CIRSE model shows some propensity to accumulate errors in energy minimization as well as rotamer optimization, but these errors are consistent enough that CIRSE correctly identifies the relative solvation energies of designed sequences as well as putative docked complexes. We analyze the errors accumulated by the CIRSE model during each type of simulation and suggest means of improving the model to be generally useful for all-atom simulations.

Keywords: protein docking, protein design, pair-additive, solvation, Poisson electrostatics, rotamer library, dead-end elimination

Flexible protein docking (Jackson et al. 1998; Lopez de la Paz et al. 2001; Lorber et al. 2002; Gray et al. 2003; Wang and Wade 2003; Zacharias 2003b) and protein design (Dahiyat and Mayo 1997; Havranek and Harbury 2002; Kraemer-Pecore et al. 2003; Kuhlman et al. 2003) problems are different forms of the challenge of protein structure prediction. In protein docking, investigators must sample many putative interfaces between two proteins, while in protein design, researchers must simultaneously optimize both residue sequence and side-chain configuration to stabilize a particular protein fold. Atomistic potential functions that increasingly take the form of molecular mechanics force fields are being used in both applications. As these potential functions converge with detailed simulation methods, a pertinent question is whether the various pieces of the scoring functions are appropriate to one another and to the sampling technique—for instance, rugged atomistic potential functions require sampling in higher degrees of freedom than their coarse-grained counterparts (Zacharias 2003b). Besides concomitant backbone and side-chain flexibility, atomistic energy functions must be accompanied by equally realistic solvation models.

Unfortunately, accurate solvation models are particularly difficult to implement with sampling techniques that are useful for protein docking and design applications. Including explicit information about solvent molecules is far too expensive for calculations that require sampling billions of radically different protein conformations. The same sampling problem also thwarts the respected implicit solvent models (Sanner et al. 1995; Baker et al. 2001; Levy et al. 2003), which involve multibody terms, usually relating to the definition of the molecular surface and volume. Given the foreseeable computing resources, the only useful methods for ab initio protein docking and design are at least pair-additive between residues given a particular backbone structure: The self-energy of each residue is a function of its conformation and the backbone geometry only, and the interaction of two residues with particular side-chain conformations is not affected by the conformation of a third side chain. Whereas typical implicit solvent models would require recalculation of the solvation energy of an entire molecular configuration after just one side-chain movement, pair-additive methods create radical speed enhancements by decoupling multibody terms and permit certain powerful search techniques such as Dead-End Elimination (DEE) (Gordon and Mayo 1998; Gordon et al. 2002; Looger et al. 2003) commonly applied in protein design.

Previously, we showed that the solvation energy change due to bringing two proteins together as rigid bodies could be approximated in a pair-additive manner (Cerutti et al. 2005), but this method was deficient in that it could not address the solvation energy change as each partner changed shape to accommodate the other. Here, we extend the data-fitting method as the Coordinate Internal Representation of Solvation Energy (CIRSE). CIRSE retains the critical pair-additive aspects, can assess the energy of different protein conformations, and offers continuous analytic derivatives for the calculation of forces. As before, we use a linear regression scheme to compute scaling coefficients for potentials of mean force between distinct atom types as well as a distance-dependent dielectric function that is independent of environment. Again as before, we fit to a Poisson/Surface-Area model; CIRSE should thus be considered in the context of Generalized Born models, particularly the models developed by Pokala and Handel (2004) and by Marshall et al. (2005), which are similar for their pair-additive qualities. To improve transferability and ensure correct derivatives in CIRSE, we fit to atomistic energies available from our benchmark model and constrain coefficients that are poorly sampled. Finally, we improve the implementation by using simple cubic spline basis functions that can be calculated on-the-fly with minimal table lookup.

The accuracy of CIRSE is limited by the accuracy of its benchmark, which in this instance is based on Poisson electrostatics and a surface-area-dependent apolar term. This type of solvent model has been investigated in numerous publications (Sitkoff et al. 1994; Sheinerman et al. 2000; Noskov and Lim 2001; Luo and Sharp 2002; Dong et al. 2003; Gohlke et al. 2003; Fogolari and Tosatto 2005). We are also investigating the validity of the particular MM-PBSA models behind CIRSE for assessing the binding energy of a series of barnase/barstar mutants (K. Litchfield, D. Cerutti, and J.A. McCammon, in prep.). In the present study, we show that CIRSE reasonably tracks its benchmark model during operations that are typically encountered in protein docking and design: rotamer-based optimization, residue replacement, and energy minimization. The performance of CIRSE in these tests suggests that it is a useful solvation energy approximation, although we identify limits to its applicability. We discuss these challenges with respect to further development of the CIRSE solvation estimator.

Results

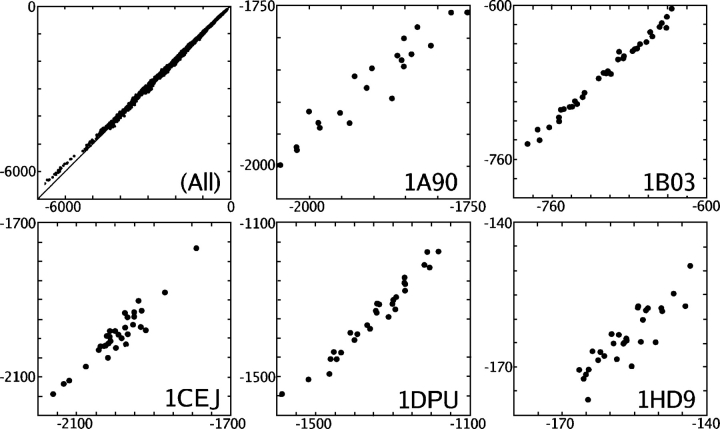

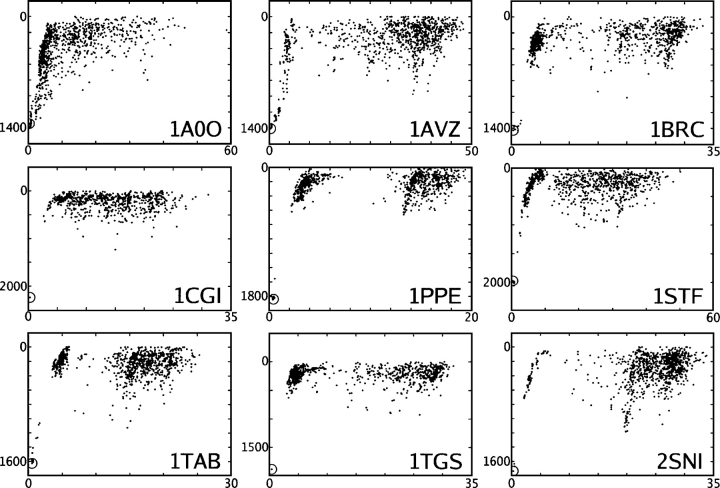

Prediction of native protein solvation energies

To be useful, CIRSE must reliably predict ΔGsolv, the energy change of inserting a protein with a specific conformation into water, as well as ΔΔGsolv, the difference in ΔGsolv of two distinct conformations of the same protein. To test CIRSE in the case of native proteins, a set of 331 NMR structures was collected from the PDB as described in “Test Cases” in Materials and Methods. P/SA calculations were performed as described in “The Solvation Energy Benchmark” in Materials and Methods for every conformation of each member of the set (a total of 6939 structures). The total solvation energy obtained for all 6939 structures correlated with the benchmark model by a coefficient of 0.9994, although the slope of the predictions of the benchmark energies was 0.977 with a Y-intercept of 1.6 kcal/mol. The mean correlation within each of the 331 NMR ensembles was 0.951 ± (with standard deviation) 0.047. CIRSE predicted ΔGsolv for all structures with an error of 46.0 ± 35.8 kcal/mol (3.0% ± 1.9% of benchmark values). The prediction of relative solvation energies should be evaluated distinctly from the prediction of overall solvation energies. Similar to what has been observed with other models (Gohlke et al. 2003), CIRSE exhibits a tendency to predict ΔΔGsolv between structures within a particular NMR ensemble more accurately, albeit only slightly, than ΔGsolv. Stated differently, the mean value of the error in ΔGsolv is not zero—thus, we label it the “(ensemble-dependent) bias.” If these ensemble-dependent biases are subtracted from the errors in ΔGsolv, CIRSE predicted ΔΔGsolv for each system with an error of 15.8 ± 9.6 kcal/mol (0.91% ± 0.44% of benchmark values). CIRSE predictions for ΔGsolv of all structures are plotted against the P/SA benchmark energies in Figure 1. Five representative ensembles are shown individually for comparison (1A90, 1B03, 1CEJ, 1DPU, and 1HD9; CIRSE estimates correlate with the P/SA benchmark by 0.95, 0.99, 0.95, 0.98, and 0.88, respectively).

Figure 1.

CIRSE predictions of total solvation energy (Y-axis, kilocalories per mole) for structures in 331 NMR ensembles plotted against the P/SA benchmark energy (X-axis, kilocalories per mole). Aggregate results are shown in the top left panel with a 1:1 trendline; results for five individual ensembles are shown in other panels.

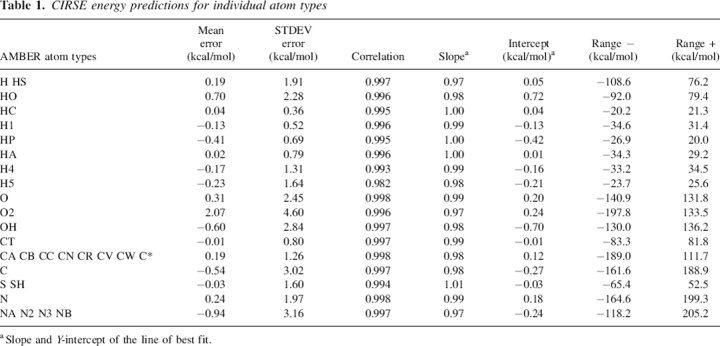

As did the total energy predictions, the atomistic energy predictions of CIRSE correlated very highly with those obtained from the benchmark model (Table 1). Predictions for the energy of individual atoms were compared to the benchmark energies for the first structure of each NMR ensemble. In terms of proportionate error, CIRSE was least accurate in predicting the energies of the rare H5 atom type, corresponding to hydrogen on the Cɛ atoms of histidine imidazole rings. As examples, CIRSE estimates for the CA (sp2-carbon), H5, O2 (carboxylic oxygen), and N (backbone/amide nitrogen) atom types are plotted against the P/SA benchmark energies in Figure 2. Here and elsewhere in this article, unless otherwise noted, references to atom types refer to the CIRSE atom types, which are related to atom types in the AMBER ff99 force field as described in Table 1. In a previous CIRSE implementation trained without atomistic energy information (data not shown), we observed striations in predictions of atomistic energies for particular atom types—there were often two or more streaks of correlated values, each with slopes of roughly 1.0 but with intercepts differing by 20 kcal/mol or more. This behavior is greatly reduced in the current atomistic predictions.

Table 1.

CIRSE energy predictions for individual atom types

Figure 2.

CIRSE predictions of atomistic solvation energy (X-axis, kilocalories per mole) compared to the P/SA benchmark (Y-axis, kilocalories per mole) for four atom types. The names depicted in each subplot correspond to the first of one or more AMBER atom types enumerated in Table 1. Data in this figure comprise one structure of each of the 331 NMR ensembles used to validate CIRSE.

To probe the source of the systematic error in predictions of the NMR structures’ total energies, a subset of the training set proteins, all structures derived from PDB entries 1A??, 1B??, or 1C?? (where ? represents any alphanumeric character) were set aside while CIRSE was retrained on the remaining globular proteins. The structures set aside contained 273 native proteins and proportionate numbers of proteins with randomized sequences or distended structures. The slope of CIRSE predictions on the benchmark model for the native globular protein structures set aside was 0.996, while that for structures with randomized amino acid sequences was 1.000 and that for the distended structures was 0.999. The Y-intercepts of each line of best fit were −9.8, 1.5, and 1.3 kcal/mol, respectively.

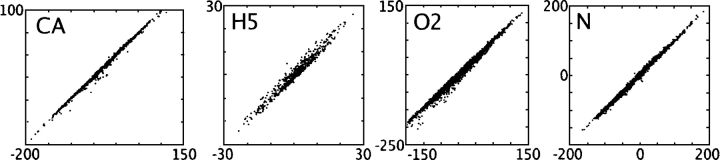

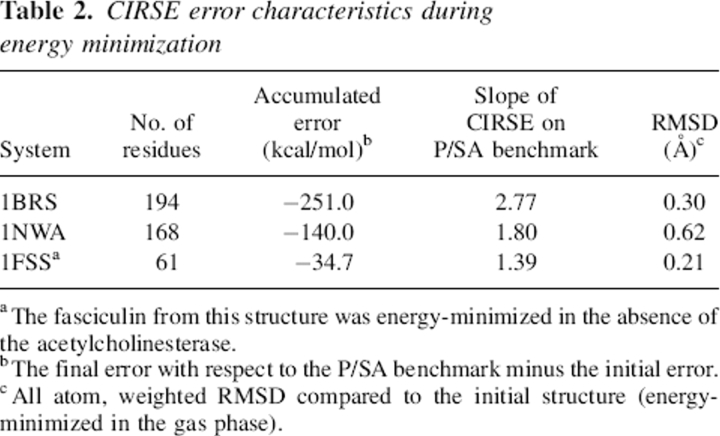

Performance during energy minimization

Energy minimization is a critical step in many docking or design protocols as well as protein simulations in general. CIRSE was examined for adherence to its P/SA benchmark over the course of minimizing three protein systems under the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential (AMBERgp refers to the AMBER ff99 gas-phase interactions only; see “Test Cases”/“Energy Minimization” in Materials and Methods for a detailed description). Figure 3 shows the CIRSE estimates of solvation energy plotted against P/SA calculations taken after each minimization step. In general, the solvation energy component became more negative, and the CIRSE estimates were highly correlated with the P/SA benchmark. However, the CIRSE model fell into spurious minima, causing the CIRSE energy to decrease somewhat faster than the actual P/SA energy and accumulate error with respect to its benchmark (Table 2) through the course of each minimization. We observed the Generalized Born model of Onufriev, Bashford, and Case (GBOBC) (Onufriev et al. 2002; data not shown) to likewise find spurious minima, but not to as great a degree. For instance, during Brn:Brs minimization, GBOBC energy estimates are likewise very well correlated with their own Poisson benchmark but have a slope of 1.33 on the values of that benchmark and thus introduce −68.2 kcal/mol error into the Poisson energy estimates.

Figure 3.

Energy minimization of three proteins using the CIRSE potential in conjunction with AMBER ff99. The P/SA benchmark solvation energy is plotted on the X-axis and the CIRSE estimate on the Y-axis. All units are kilocalories per mole. The CIRSE energy was observed to decrease steadily over the course of each minimization (solid line), although more rapidly than the actual benchmark solvation energy (dashed line indicates X = Y).

Table 2.

CIRSE error characteristics during energy minimization

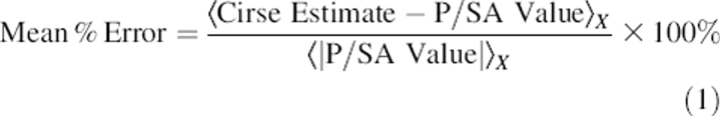

To further investigate the accumulation of errors in CIRSE during energy minimization, the training set protein structures 1A??, 1B??, 1C?? (where ? represents any alphanumeric character), were energy-minimized using the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential. The CIRSE predictions for the minimized structures of these 273 proteins had a slope of 1.11 on the P/SA benchmark with a Y-intercept of 78.3 kcal/mol. Across all atom types, analysis of atomistic energy predictions indicated significant differences, as judged by a Student's t-test with α = 0.005, between the errors obtained before and after energy minimization. To compare the changes in the CIRSE errors across different atom types with widely different solvation energies, we computed the mean percentage error for each atom type as in Equation 1:

|

where 〈…〉X denotes an average over all instances of atom type X and looked for changes in this quantity after some operation such as energy minimization. CIRSE estimates for heavy atom types O, O2, CT, N, and CA (corresponding to carbonyl oxygens, carboxyl oxygens, sp3-carbons, amide nitrogens, and sp2-carbons, respectively) all showed positive shifts of up to 1.2% in the mean percentage error; all other atom types showed negative shifts. Most significant were the changes in mean percentage error for the rare hydrogen atom types, particularly H5, which shifted downward by 9.9% during energy minimization. There was a moderate correlation (0.62) between the change in the mean percentage error and the logarithm of the number of instances of a particular atom type.

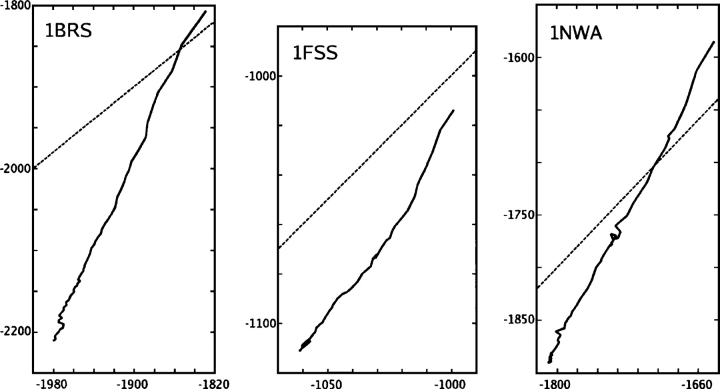

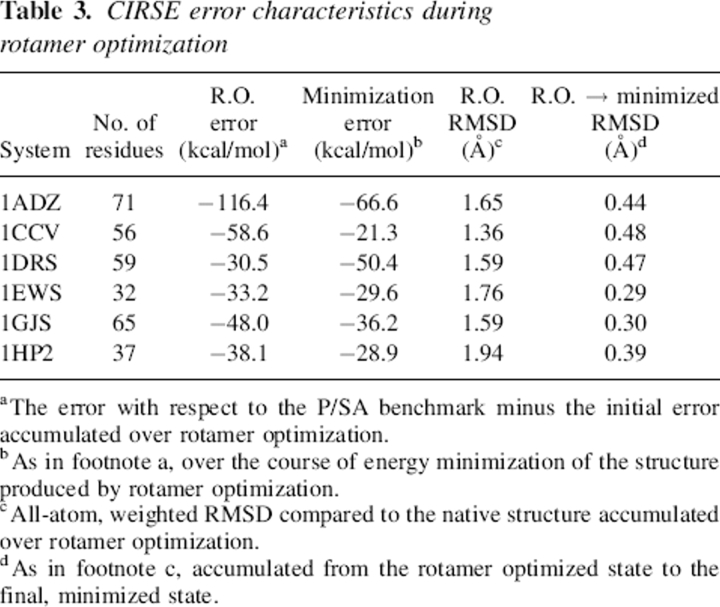

Performance during rotamer optimization

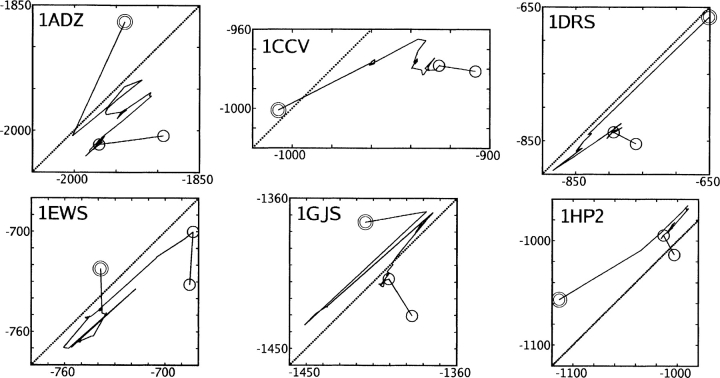

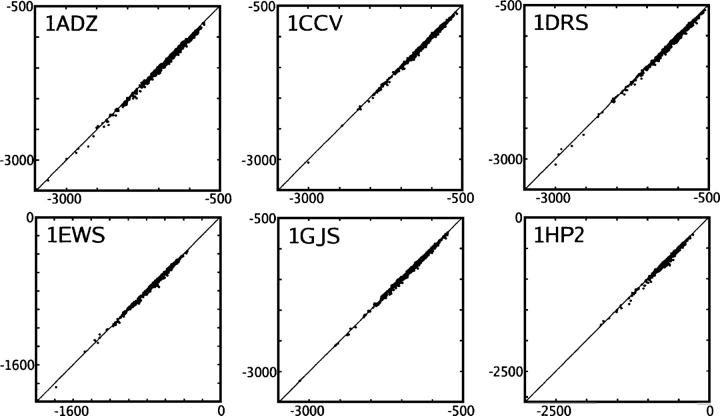

Rotamer-based refinement differs from local energy minimization in that much larger, intuitive moves of the side chains are used to seek global minima. Because our rotamer generation method did not admit backbone flexibility, involved no bond stretching, and permitted only a limited number of angle flexions, this test also provided an opportunity to determine whether CIRSE could accumulate significant error in nonbonded interactions. Figure 4 depicts how CIRSE tracked its benchmark over the course of rotamer optimization and subsequent energy minimization for each of the six proteins. To demonstrate the performance of the Low(DEE/SimAn) method used here (repeated moves consisting of Dead-End Elimination and Simulated Annealing were accepted only if they lowered the energy of the side-chain configuration; see “Test Cases”/“Rotamer Optimization” in Materials and Methods for a detailed discussion of the technique), Figure 5 shows the total energy of each system over the course of global and patch refinements as well as energy minimization (see “Test Cases”/“Rotamer Optimization” in Materials and Methods for descriptions of the “global” and “patch” refinement procedures).

Figure 4.

Rotamer optimization of six native structures using the CIRSE potential in conjunction with AMBER ff99. The P/SA benchmark solvation energy is plotted on the X-axis and the CIRSE estimate on the Y-axis. All units are kilocalories per mole. Concentric circles indicate the original structure; native side-chain configurations were removed. The solid black line traces global refinement followed by 50 patch refinements; the final segment, bracketed by separate circles, corresponds to energy minimization of the re-packed structure. The PDB ID of each structure is given in the top left corner of each subplot.

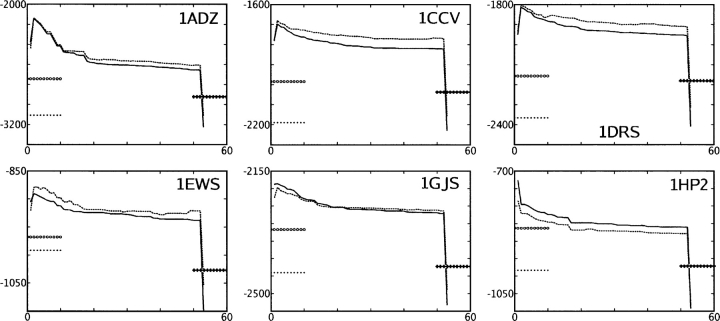

Figure 5.

Total energy of six systems (Y-axis, kilocalories per mole) according to the AMBERgp + CIRSE potential during the course of rotamer optimization and energy minimization (X-axis, step 1 → 2 being global refinement, steps 2 → 3, …, 51 → 52 patch refinement, 52 → 53 unconstrained energy minimization). The PDB ID of each system is listed in its subplot. (Solid line) CIRSE + AMBERgp energy, (dashed line) P/SA + AMBERgp energy, (+ line segment) energy of the state obtained after the final patch refinement minimized with a fixed backbone, (• line segment) CIRSE + AMBERgp energy of the NMR structure minimized according to the same potential, (○ line segment) CIRSE + AMBERgp energy of the NMR structure minimized with a fixed backbone.

Rotamer optimization exposed limitations of the CIRSE model distinct from those shown by simple energy minimization. The magnitudes of the errors accumulated by the rotamer optimization (see Table 3) were comparable to those created by energy minimization, particularly when the size of each system is taken into account. However, because backbone, bond stretching, and most angle degrees of freedom are not sampled in the rotamer optimization, this indicates that substantial artifacts can arise from just the nonbonded interactions involving side-chain atoms.

Table 3.

CIRSE error characteristics during rotamer optimization

The net effect of energy minimization with CIRSE, though small, is never well correlated with the P/SA benchmark for any of the six systems, and for four of them the correlation is negative. This is not a contradiction of the previous findings with respect to energy minimization; for instance, if the structures obtained directly from the NMR ensembles of each protein were minimized with the AMBERgp + CIRSE potential, the change in CIRSE solvation energy was also on the order of tens (as opposed to hundreds) of kilocalories per mole and not well correlated with the P/SA benchmark. When the rotamer-optimized structures were first minimized with respect to AMBERgp alone, minimization with AMBERgp + CIRSE reoptimized the solvation effects, and, over the larger range of solvation energies, CIRSE tracked the P/SA benchmark in a manner similar to that shown in Figure 3.

With the detailed rotamer library used in this test, the Low(DEE/SimAn) scheme appears to be effective at discovering values of the energy such that additional rounds of the algorithm could not further reduce the energy, as shown in Figure 5. The energy of each system generally increased during the global optimization step because the native side-chain configurations were deleted; in systems 1ADZ and 1HP2, HERO failed to converge to a combinatorial number of possibilities <107, which we were willing to sample systematically, so the minimum energy in these global refinements had to be assayed by SimAn. It is likely that HERO failed to converge for some of the patch optimizations, as flat portions of the total energy curves in Figure 5 indicate that the previous configuration was kept after some steps of patch refinement. To outline some other regions of each system's energy landscape under the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential, Figure 5 also depicts the energies obtained by energy-minimizing the native state with or without a fixed backbone and by energy-minimizing the rotamer-optimized state with a fixed backbone.

The final energy minimization step decreased the energy much further than the rotamer optimization, but this is due to relief of steric clashes (an energy landscape too rugged for any rotamer-based scheme) and electrostatics rather than solvation effects, as a comparison of the total relaxation depicted in Figure 5 with the relaxation in the solvation energy depicted in Figure 4 shows. During energy minimization of the six structures, the relaxation in electrostatic potential energy was 55% ± 32% of the relaxation in Lennard-Jones energy. With the exception of system 1EWS, the degree of relaxation observed by energy-minimizing the state obtained by rotamer refinement is roughly equal to that for the original NMR structure, and the relaxation observed in either case is cut in half by restraining the backbone atoms. In all cases, a lower potential energy is ultimately obtained by energy minimization of the rotamer-optimized state as opposed to the native state.

Performance in protein design

Protein design is a more strenuous application of the rotamer-based refinement that is often seen in protein docking applications. Although, in practice, protein design involves simultaneous optimization of sequence and side-chain conformations, this digresses into issues concerning “negative design” (Havranek and Harbury 2002; Mooers et al. 2003) that are beyond the scope of this paper. Negative design is the process of evaluating different sequences based on the relative stability they confer to the desired fold versus the stability they confer to undesired ones. Briefly, allowing optimization of the sequence creates, in the basic thermodynamic sense, an open system, whereby rotamer optimization methods can obtain lower potential energy configurations by introducing more matter with highly favorable interactions. However, the sequence that minimizes the potential energy of a given fold will not necessarily adopt that fold, even under the same simulation force field.

If sequence optimization is permitted (e.g., rotamers from many residues are used to pack the side chains of single residues on the backbone template) without considering the relative stability of the desired fold versus the stability of other folds, our Low(DEE/SimAn) optimization algorithm, in conjunction with the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential, displayed a propensity for mutating surface residues to arginine. When performing sequence optimization, a first-order correction is to evaluate the self-energy of each rotamer relative to the self-energy of the corresponding amino acid isolated in solvent. For example, the energy of an arginine residue folded up against a tightly coiled backbone would be evaluated relative to the internal energy of the amino acid arginine, in an extended conformation, alone in solvent. When this correction was invoked, a propensity for mutating surface residues to tryptophan was observed. These results do not shed light on the accuracy of CIRSE with respect to its benchmark, although they do suggest that, in protein design applications of CIRSE, negative design would be imperative.

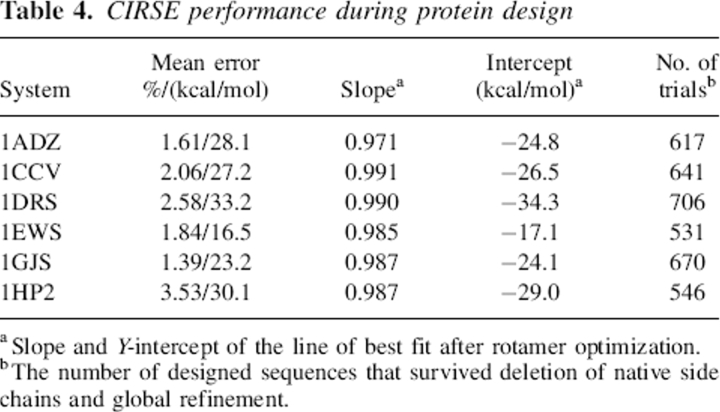

Figure 6 depicts the CIRSE estimates of solvation energy after extensive rotamer-based optimization. Out of the 1000 trials for each system, up to 469 failures occurred. In such cases, the set of non-native rotamers supplied for refinement could not find a solution without steric clashes exceeding 1000 kcal/mol, despite the fact that a clash-free solution presumably existed after energy minimization in vacuum. The success rate is noted in Table 4, but failures were omitted from the correlation statistics. Despite some difficulties tracking its P/SA benchmark over the course of rotamer optimization, the correlations are recovered for ranking hundreds of different sequences grafted onto similar backbone templates. As Table 4 shows, the percentage errors in ΔGsolv are comparable to or better than those obtained for native NMR ensembles. The error in ΔΔGsolv for all systems, which again is computed by subtracting the mean error of each system from the error in estimates of ΔGsolv, is 21.5 ± 3.2 kcal/mol. The slope of the CIRSE predictions on the actual P/SA benchmark is closer to 1.0 for these designed systems, unlike that observed for native complexes and the same randomized sequences that had not undergone rotamer refinement (see below). Furthermore, the Y-intercept of the line of best fit is consistently negative, between −17.1 and −34.3 kcal/mol.

Figure 6.

CIRSE estimates (X-axis, kilocalories per mole) of the energy of hundreds of random amino acid sequences plotted against the P/SA benchmark energy (Y-axis,kilocalories per mole). As in Figure 4, the label at the top left corner of each subplot denotes the PDB ID of the template.

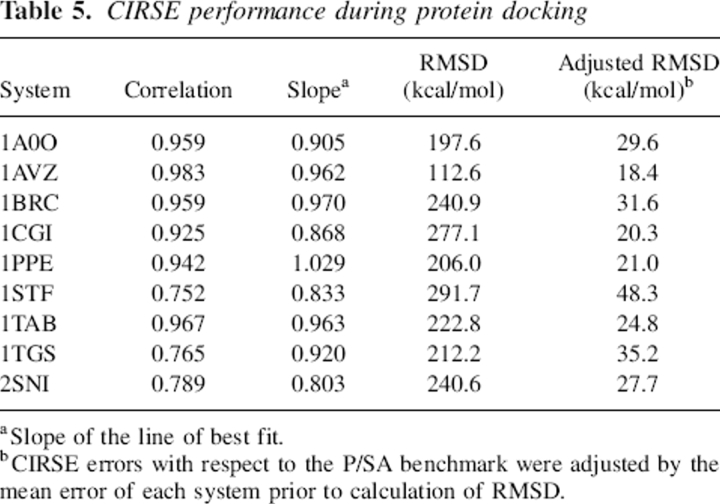

Table 4.

CIRSE performance during protein design

To probe the source of errors in protein design applications, particularly the noticeably different slope of CIRSE predictions on the P/SA values, the atomistic energy estimates of CIRSE were compared to those of the benchmark for the designed sequences grafted onto each of the six templates before and after rotamer refinement (again, omitting those sequences that were not successfully repacked by our algorithm). Averaged over all six systems, the CIRSE estimates of the structures taken before rotamer optimization showed slopes of 0.974 ± 0.003 with Y-intercepts of −6.58 ± 4.85. The errors in energy estimates of nearly all atom types, with the exceptions of types O and N, are affected by rotamer refinement as judged by a Student's t-test with α = 0.005. Atom type HO was the only atom type to see a positive direction change (0.9%) in the level of the mean percentage error with respect to the P/SA benchmark; in all other atoms types, the direction of the change was negative, reflecting the fact that the total energy estimate was generally closer to the benchmark value after rotamer optimization in CIRSE. As a result of rotamer refinement, the mean error in energy estimates for rare atom types such as H4, S, and H5 shifted by as much as 6% of the total atomic solvation energy. There was a 0.79 correlation between the degree to which rotamer refinement shifted the mean percentage error in atomic solvation energy estimates and the logarithm of the frequency with which that atom type occurred in the designed sequences.

Performance in protein docking

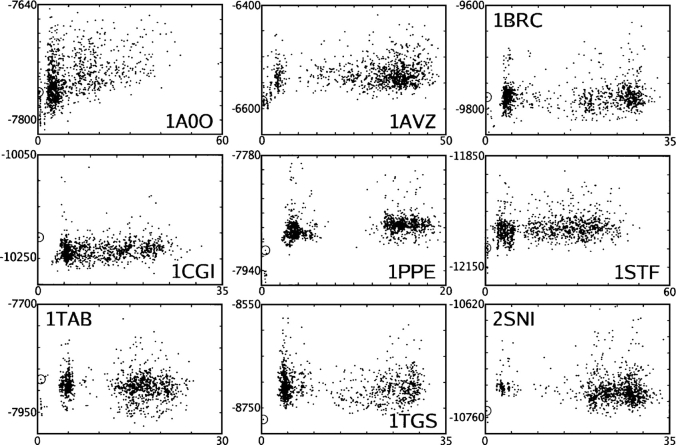

The initial purpose of the ELSCA scoring function (Energy by Linear Superposition of Corrections Approximation) (Cerutti et al. 2005) and its evolution into CIRSE was to merge implicit solvent models with pair-additive scoring functions that are useful in protein docking. Protein design applications were made possible as an additional benefit of the pair-additive nature of the scoring function. The primary goal of the docking was to show that CIRSE tracks its benchmark over the course of creating many different protein–protein interfaces. The correlations and absolute deviations for CIRSE estimates versus the P/SA benchmark for all nine protein–protein complexes are shown in Table 5. Additionally, because the docking provides an opportunity to test the durability of CIRSE under simultaneous rotamer optimization and energy minimization, we checked for the existence of “score funnels,” energy landscapes possessing the shape of a funnel near the correct binding configuration, in this application of an ab initio force field to protein docking, as illustrated by Figures 7 and 8.

Table 5.

CIRSE performance during protein docking

Figure 7.

AMBERgp + CIRSE estimates of the energy of 1000 docked complexes as well as the native complex (circled) for bound coordinates of each of nine interacting protein pairs (Y-axis, kilocalories per mole) plotted against RMSD from the crystal structure (X-axis, Å).

Figure 8.

Degree of buried SASA (Y-axis, Å2) of 1000 docked complexes as well as the native complex (circled) for bound coordinates of each of nine interacting protein pairs (Y-axis, kilocalories per mole) plotted against RMSD from the crystal structure (X-axis, Å).

Refinement of the DOT suggestions (putative protein–protein complexes suggested by the DOT software; see “Protein Docking” in Materials and Methods) (Mandell et al. 2001) using extensive side-chain optimization and the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential spread apart many proposed complexes, putting a layer of water between the two proteins with little buried surface area in the interface. As was shown previously (Cerutti et al. 2005), even with a much less sophisticated docking method, a scoring function relying only on steric interactions and torsional potentials was able to find numerous non-native configurations of two interacting proteins that buried more surface area than the native complex. We do not show data, but we also observed the AMBERgp potential, in the absence of CIRSE but with the docking approach used in this paper, to increase the buried surface area of many complexes over that predicted by the addition of CIRSE. With CIRSE + AMBERgp, however, the native complexes show much more buried surface area than the non-native ones. Furthermore, as shown by Figure 8, score funnels for most complexes are recovered by measuring the surface area buried in each proposed interface. Systems 1CGI and 1TGS do not show obvious score funnels with respect to buried surface area, but the native complexes are still distinct.

The correlations observed in the CIRSE versus P/SA energy estimates of the final docked complexes (Table 5) are not as good as those observed for native structures obtained from NMR ensembles. The deviations in estimates of ΔGsolv are very negative and amount to roughly 7% of the total energy estimate in most systems, but when compared to the benchmark solvation energy, the errors in ΔΔGsolv (0.7% ± 0.2% averaged over all nine systems) compare well with the same quantity calculated for the NMR ensembles (0.91% ± 0.44%).

Discussion

Reproducing solvation energies of native structures

The CIRSE approximation is remarkably good at fitting its solvation energy benchmark for structures such as the NMR ensembles that were generated independently of the CIRSE potential. The absolute error in the total solvation energy of different protein configurations is only slightly higher than the error in the relative solvation energy differences between configurations of the same protein. This is not the case with some modern Generalized Born models (Gohlke and Case 2003), which fit the relative solvation energies well but absolute energies very poorly. The errors in CIRSE's absolute solvation energy estimates are systematic, as shown by the 0.977 slope of the predictions on the benchmark energies. The fact that CIRSE estimates for proteins removed from the training set are correctly scaled suggests that the errors in estimates of the NMR test set stem from fundamental differences between the NMR structures and the crystal structures. These systematic errors likely arise from the way crystal structures or random sequence derivatives of those structures were refined prior to use in the training set: by gas-phase minimization, to which the NMR structures were not subjected. As was shown by comparing the rotamer optimization tests with the energy minimization tests, the solvation energy of the NMR structures is very close to a local minimum with respect to the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential, but minimization of any structure with the AMBERgp potential alone creates significantly unfavorable solvent effects. In crystal structures, which are often collected at cryogenic conditions (Halle 2004) or contain crystal packing artifacts, and particularly in the set of chains we extracted by homology culling, a realistic solvated state for the surface side chains at standard temperature is not easy to determine. Nonetheless, it appears that side chains in their preferred solvated conformations were not adequately represented in our training set. Inclusion of NMR structures in the CIRSE training set would be very simple and could improve the fit in a wider variety of proteins.

The fact that CIRSE reproduces not only absolute and relative solvation energies but also the solvation energy of individual atoms is a strong indication that CIRSE gives useful information about solvation effects and that, to a good approximation, the P/SA solvation model can be decomposed into purely pair-additive terms. The range of solvation energies for many of the atom types indicates that the P/SA potential energy surface is extremely rugged. While the solvation energy of entire proteins is on the order of thousands of kilocalories per mole, the solvation energy of individual polar hydrogen atoms, of which there are dozens if not hundreds in a single protein, can vary as much as 200 kcal/mol. That of oxygen, nitrogen, or even certain carbon atoms can vary by more than 300 kcal/mol. Whether these atomistic energies are realistic is somewhat difficult to say; the correct reproduction of ionic solvation energies by the Born formula (Born 1920) indicates that the solvation energy of charged spheres can indeed be very large; however, the P/SA benchmark model is not expected to reproduce the discrete effects of water molecules on surface atoms, particularly those that can participate in hydrogen bonding.

Probing the weaknesses of the CIRSE approximation

Both rotamer optimization and energy minimization, the principal operations of protein docking and design, expose CIRSE's propensity to find spurious minima. Taken together, Tables 2 and 3 show that these minima can arise even when bond length and most angle bend degrees of freedom are constrained. Nonetheless, the protein docking results shown in Table 5, in which both rotamer optimization and energy minimization were used, demonstrate that the accumulation of errors takes place consistently enough that the relative solvation energies of moderately different conformations of one protein (or, in the case of docking, a pair of proteins) can still be obtained accurately. However, the results of the protein docking test do not ensure that CIRSE could accurately predict the relative solvation energies of larger conformational changes, such as folded and unfolded proteins. In protein folding applications, CIRSE might still be useful for generating trial moves as part of a biased Monte Carlo scheme, where moves were ultimately accepted or rejected based on rigorous evaluations of the energy using the CIRSE benchmark model.

Both energy minimization in hundreds of proteins (see “Performance During Energy Minimization” in Results) and rotamer optimization of thousands of randomized sequences of small proteins (see “Performance in Protein Design” in Results; Table 4; Fig. 6) showed the tendency of the CIRSE model to accumulate errors in rare atom types. The first recourse to solving this problem, more sampling, is simple enough to accomplish. However, because a considerable amount of CPU time was spent computing Poisson calculations for the training set alone, it is desirable to consider only the most useful structures. The same energy refinement techniques that elucidated failures in CIRSE's ability to track its benchmark could be applied to another set of proteins under the current CIRSE + AMBERgp potential to generate a new list of structures containing examples of the errors CIRSE currently makes. This set of structures could be added to the training set; if fruitful, the process could be repeated several times to create increasingly robust CIRSE models. It must be noted, however, that the errors in rare atom types and the errors accumulated by minimization in general are also, to some degree, an intrinsic property of the CIRSE potential. With a tremendously detailed training set, a set of pair potentials could be fit with very fine basis functions. Such ideal pair potentials, the best possible for the given set of atom types, would naturally, on average, predict the energies of all possible protein structures to within a certain precision, 2% or less judging by the results of the NMR test set. However, energy minimization would still seek out the residuals in such a model and thus accumulate errors. Further development of the CIRSE model will help clarify whether this “hard limit” has been reached.

The thoroughness of the sampling used to detect accumulating errors in the CIRSE potential also must be evaluated. The all-atom RMSD values shown for each of the six structures in Table 3 demonstrate how structures that have undergone rotamer optimization with rigid backbones display four to six times more movement overall than the equivalent structures that were energy-minimized in the coordinates of all atoms. Other groups have noted the insufficiency of rotamer libraries with the detail of the Dunbrack and Karplus library used in this work (Dunbrack and Karplus 1993) and have devised different ways around it, ranging from generating additional rotamers by dynamic minimization in torsional angle space (Wang et al. 2005) to feeding incredibly large rotamer libraries into the calculation (Xiang and Honig 2001; Peterson et al. 2004). Both approaches, however, search only torsional angle space, despite other findings (Mendes et al. 1999) that angle bending is necessary for some cases of side-chain packing. Although searches using only the most populated torsion angles and no bond or angle flexibility appear to be very successful for protein docking (Wang et al. 2005), to further relax our side chains and propose more rigorous decoys, we chose to sample nonequilibrium angles as well as off-rotamer torsions. The convergence of each protein's energy during the rotamer optimization phase suggests that, for the available degrees of freedom, the Low(DEE/SimAn) algorithm was able to operate on the available rotamer library to get very close to the global minimum obtained by searching infinitely many rotamers. However, it remains to be seen whether the same rotamer optimization protocol, when run with different random seeds to provide different rotamer libraries, leads to convergent results in terms of energy and the placement of side chains in each system. The fact that energy minimization in the positions of side-chain atoms alone evoked a relaxation comparable to or greater than that of rotamer optimization suggests that the higher-frequency bond and angle flexions still greatly influence the energy landscape. It also remains to be seen whether the potential energy of different rotamer-optimized states has any correlation to the potential energy of those states after energy minimization—that is, whether such extensive rotamer optimization is worthwhile in applications apart from testing CIRSE.

Protein design

The fact that CIRSE predicts the solvation energies of hundreds of rotamer-optimized structures with percentage errors comparable to those of native structures suggests that it is just as useful a solvation model for protein design as it is in rescoring independently generated structures. The errors CIRSE accumulated over this process appear to have shifted the energy estimates proportionately, as shown by the different slopes and intercepts of the lines of best fit for CIRSE estimates on the P/SA benchmark before and after rotamer optimization. Although the slope of these lines of best fit is closer to 1 after rotamer optimization, the compensation was likely fortuitous; had the sequences been grafted onto one of the globular protein structures, where there was not a tendency in CIRSE to underestimate the magnitude of the solvation energy, the errors would probably have driven the total energy estimates away from the target values.

The failure rate in these tests is significant, but acceptable given the stringent packing requirements imposed by the standard Lennard-Jones potential used. Although it can be safely assumed that minimization by AMBERgp created clash-free structures for each of the 1000 random sequences grafted onto each backbone, the high failure rates for the initial repacking step indicate that several side chains were forced into abnormal conformations, such that a library of roughly 1350 rotamers could not find replacements wherein no pair of residues clashed by >1000 kcal/mol. This does not necessarily suggest that the level of detail in the rotamer libraries was inadequate throughout the whole process; the global refinement phase was carried out with a 1350-rotamer library, as opposed to the patch refinements, which were carried out with a 3600-rotamer library, for computational tractability.

Protein docking

Our protein docking studies combined both energy minimization and rotamer optimization techniques, providing an opportunity to test CIRSE's performance under both procedures in the context of forming many different interfaces of the same proteins. The docking technique we used is most similar to that used by Gray et al. (2003), the most significant change being that each of the docked structures was subjected to an additional round of energy minimization to a very tight convergence, while all atoms, including the backbones, were unconstrained. Technically, this procedure entailed docking with complete protein flexibility, but practically, the movements of the individual proteins’ backbones were very slight, as suggested by the all-atom RMSD values of other energy-minimized structures in Tables 2 and 3. As Figure 5 might suggest, the slight movements created by energy minimization nonetheless correspond to large energy changes for both side-chain as well as backbone atoms; the final, unconstrained energy minimization therefore sampled the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential energy landscape much more deeply than the original, rigid-backbone docking procedure.

The CIRSE deviations from its P/SA benchmark are quite large and negative in all cases, but they are a fairly consistent proportion of the total P/SA solvation energy. While the sources of the large bias in these estimates have been thoroughly probed through our tests of energy-minimized and rotamer-optimized complexes, the relative solvation energy differences in complexes of the same two protein partners, given in Table 5, are comparable to those between the individual members of an NMR ensemble (see “Prediction of Native Protein Solvation Energies” in Results). This suggests that, however CIRSE's accuracy is breaking down, the errors are consistent enough to retain some degree of precision in the results.

As shown in Figure 7, the CIRSE + AMBERgp potential rarely produces score funnels in the docked structures. However, this should be considered with the findings that this potential also spreads apart many complexes. Taken together, these findings suggest that native complexes can still be discriminated by the degree of buried surface area. Essentially, CIRSE seems to predict that a layer of water will separate two proteins until they reach a state very much like the docked complex, at which point it is energetically permissible to bring them closer together, despite the fact that omitting the CIRSE and electrostatic components will permit large, non-native interfaces to form (Cerutti et al. 2005). For blind docking studies, the use of an attractive potential between the two proteins, which would not be included in the final energy score, might help to distinguish native from non-native arrangements on the basis of the total energy of each putative complex alone. Finally, we emphasize that the docking procedure attempted here used an ab initio scoring function; other successful docking programs have involved ad hoc tuning of the energy estimators (Vakser and Aflalo 1994; Gray et al. 2003; Zacharias 2003b) to improve results.

Future directions

The CIRSE potential approaches the limits of implicit solvent model accuracy under the constraint of pair-additive interactions between solute atoms. A previous work (Vasilyev 2002) tested the existence of an effective dielectric function ɛ(r), to which CIRSE's distance-dependent dielectric corresponds, for reproduction of polar solvent effects. The CIRSE fitting routine, followed by tests similar to those presented in this paper, could be used to determine the upper bound of accuracy in such a model, but our experience suggests that to obtain a useful model, separate pair potentials for many different atom types are necessary in addition to an environment-independent ɛ(r). First, we note the most successful aspects of the current implementation: the atomistic fitting scheme and the form of the CIRSE basis functions. Next, and in addition to improvements in the training set already discussed, we outline two major avenues for improving the CIRSE model: the types of pair potentials and the nature of the solvation energy benchmark.

The method of fitting CIRSE based on atomistic solvation energies is easily implemented within the context of our linear fitting scheme, and can be thought of as analogous to the method recently implemented for training Generalized Born models by fitting the GB radii to those obtained by Poisson's equation (Onufriev et al. 2002). Besides reducing compensatory errors in the fit and providing a means of dissecting CIRSE energy estimates, the atomistic information was helpful in that it reduced the total number of structures needed to obtain a good fit as each structure contributed 10 linearly independent data points. However, future development may focus on different solvation energy benchmarks that cannot (easily) provide atomistic information, such as free-energy perturbation in explicit solvent (Swanson et al. 2005; Woo and Roux 2005). In such cases, because the derivatives of the CIRSE function are analytic and linear in the fitted coefficients, these values could be fitted with atomistic information about the mean force on individual atoms. Indeed, the GRAPPLE software that implements both CIRSE applications and its fitting scheme is equipped to take information about such forces. This feature was not used in the fitting because the particular P/SA benchmark we chose, involving a multibody solute volume definition and surface-area terms, does not yield forces for individual atoms. CIRSE was thus trained to interpolate between the energies of structures with perturbed atoms to recover the derivatives of solvation energy.

The form of the CIRSE basis functions is exceptionally efficient and will not likely need modification. For any value of rij, the distance between two atoms i and j, at most two of the basis functions have values that must be calculated by cubic splines while all others have constant values. This permits the implementation of a small lookup table to store the accumulated values of the constant parts of all basis functions for every pair potential at intervals of β/2, where β is as defined in “Approximation to the Total Solvation Energy” in Materials and Methods. The values of energy are obtained by adding the values of each of the basis functions whose variable regions contain rij, each of which merely requires adjustment of rij to the spline window followed by computations of the value of the basic cubic spline and multiplication by the appropriate CIRSE scaling parameter.

Many implementations of the CIRSE model were tried prior to publication of these results. The number of atom types and the density of basis functions in each pair potential were chosen to maximize the fit obtained in the training set, although it may be possible to agglomerate certain CIRSE atom types and maintain the level of fit or split atom types such as those including CA or NA, which show considerable ranges of solvation energy in Table 1, and make a marginal improvement. The product of the respective atoms’ radii, Rij, is summed to the interatomic distance for computing the effective distance of charge-dependent interactions to recover the fact that, when two charged spheres are moved closer together and eventually superimposed, the total solvation energy of the system does not diverge as the pure Coulombic interaction does, but rather converges to the Born solvation energy of a sphere with the largest of the two radii and the sum of the two charges. The independence of Rij from environment was imposed to fulfill the goal of pair-additivity, but a prefactor could be added to this term that may improve the fit.

Another, more drastic, extension of CIRSE would be to incorporate environment dependence into the value of Rij. This could be done without sacrificing CIRSE's applicability to DEE and other rotamer optimization schemes, so long as Rij depended only on fixed components of the system, such as the positions of residue Cαs and/or a mean-field estimate of the volume and position of each residue's side chain (Pokala and Handel 2004). Introducing a multibody term like this, however, implies very complicated derivatives in the CIRSE potential. This problem is encountered in Generalized Born (GB) models, where a factor corresponding to Rij is dependent on the positions of all atoms in the system; however, due to the nature of the GB potential, computing GB forces can actually be phrased as an O(N2) problem, rather than an O(N3) one, for N atoms (for details, see the AMBER8 source code file egb.f) (Pearlman et al. 1995; Lee et al. 2002). A similar factorization might be possible with force computations given an environment-dependent Rij term. Regardless, if the multibody term applied only to the self-energy of atoms, the computation of atomic forces would be at worst O(N2 + Nn), hardly more expensive than the current computation of forces. Any of these formulations, irrespective of the complexity of force calculations, is compatible with the linear fitting scheme currently used to train CIRSE.

The pair potentials used in CIRSE have the basic form ρ(r)φ(r), where ρ(r) is a function of arbitrary form determined by the linear fitting scheme that modulates a more physically meaningful φ(r). In the present implementation, φ(r) has the forms 1 and qiqj/sqrt(rij2 + Rij), where qi represents the charge of atom i, but these are by no means the only possible forms. Although implicit solvent models are incapable of accounting for effects such as hydrogen bonding between solute and specific solvent molecules, CIRSE may be able to better emulate the time-averaged values of these effects than other implicit solvent models, given the appropriate φ(r) and a proper benchmark. If CIRSE were trained using an explicit solvent model that included hydrogen bonding, it may be able to automatically learn effects such as solvent-mediated hydrogen bonding (Ikura et al. 2004; Papoian et al. 2004; Sharrow et al. 2005) that cannot be easily incorporated into other mean-field models.

Aside from improvements to the CIRSE model itself, a better benchmark model could potentially make much larger strides toward better accuracy and realistic behavior. The P/SA calculations used in this work took anywhere from a few minutes to an hour of computing time on 3 GHz Xeon processors. As they mature, other solvent models such as integral equation theories (Beglov and Roux 1996; Liu and Ichiye 1999) and apolar energy estimates based on the solvent volume rather than the accessible surface area (Levy et al. 2003; Zacharias 2003a) could be used to fit the CIRSE potential. As computers become faster and more abundant, free-energy perturbation in explicit solvent, which currently takes hundreds to thousands of CPU hours per calculation, could also become the CIRSE benchmark.

Earlier in the discussion, we discussed a “hard limit” of CIRSE accuracy in the establishment of perfectly detailed pair potentials between a certain set of atom types fit to a gargantuan training set, and the fact that errors could still be expected to accumulate in such a model as energy refinement methods exploited the residual errors between CIRSE estimates and the true benchmark values. However, this hard limit applies to CIRSE as presently formulated; in our investigation, we have found that there are many sets of atom types and potential functions other than 1 or qiqj/sqrt(rij2 + Rij) that can also reproduce the benchmark solvation energy. These models may not necessarily have overlapping residuals, e.g., artificial minima in the same places. It may still be possible, though more computationally expensive, to average the effects of distinct CIRSE models to achieve consensus estimates of the solvation energy that are both more accurate for estimating solvation energies of independently generated structures as well as less prone to accumulate error during energy refinement.

Conclusions

We have developed a new solvation energy model, the Coordinate Internal Representation of Solvation Energy, that is pair-additive in the solute particles and, in principle, generally applicable to molecular simulations. Although we have identified some systematic errors, CIRSE is robust enough to be useful in protein docking and design problems, where it is needed most. There is great potential to improve the model, and its unique formulation and automated fitting scheme may be useful for creating implicit-solvent models that better reproduce the characteristics of explicit solvent.

Materials and methods

Approximation to the solvation energy

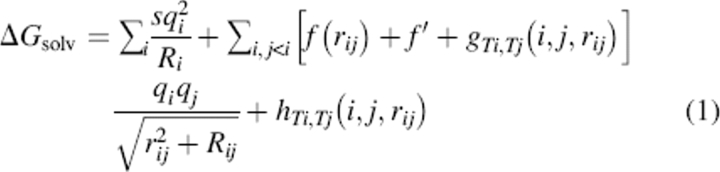

|

We use the basic linear regression technique detailed for the ELSCA scoring function (Cerutti et al. 2005) but with changes to the basis functions, nature of the pairwise potentials, and target energies. Briefly, each molecular configuration has a target energy computed by the benchmark model. The coordinates, charges, and atom types in that configuration are used to compute the values of basis functions, which are stored in one row of matrix A. The target energy is stored in the appropriate index of the column vector b. By providing many more target configurations than basis functions, an overdetermined system is created whereby the scaling coefficients for each basis function that optimally reproduce the target energies are given in the vector x by solving the linear least-squares problem (LLSP) Ax = b. The CIRSE model assumes that the total solvation energy, ΔGsolv, can be captured in the form (Equation 2):

|

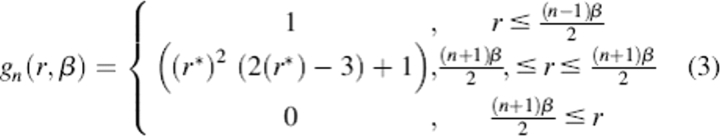

where i and j run over the atoms in the macromolecule; rij is the distance between the atoms and Rij is the product of their respective radii; q represents charge; s is a constant for the self-energy; f is a distance-dependent dielectric function that applies to all atom types and has no dependence on environment (a “uniform” dielectric function); f′ is the long-range dielectric constant; and g and h are distance-dependent pair potentials dependent on the types of atoms i and j. The functions f and h have direct counterparts in ELSCA, but the self-energy term and the pair potentials g, which modulate the local electrostatics to account for environment-dependent solvation effects, are unique to CIRSE. We take f, g, and h, which have no physical motivation and no significance except in the context of a complete CIRSE model, to have the form (Equation 3):

|

where the indexing for n begins at 1, β represents the width of the cubic spline piece of each basis function, r is the absolute distance between two atoms, and r* for the n-th basis function is equal to (1/β)[r − 0.5(n − 1)β]. As in ELSCA, β need not have the same values for functions f, g, and h. We chose β = 3 Å for the functions g and h, and β = 2 Å for f. We chose n = 4 for g, 100 for f, and 3 for h. We chose 17 atom types, the original 16 ELSCA atom types with the exception that AMBER atom type “N” was distinguished from other nitrogen atom types, for a total of 1179 parameters. The AMBER atom types that make up different CIRSE atom types may be found in separate rows of Table 1. To illustrate the detailed fitting procedure, the Supplemental Material gives pseudocode for training a CIRSE model based on a set of biomolecular structures with benchmark energy data.

Obviously, with such a large number of parameters, a unique solution is not to be expected, and transferability of the model must be tested rigorously. Because demonstrating the transferability of CIRSE is the main objective of this paper, we took several steps, each distinct from the methods used to train ELSCA, to help us reach that goal. We sampled native and non-native amino acid sequences, imposed constraint equations to eliminate steep potential functions, randomly subdivided each training configuration to prevent compensatory effects arising from residue topologies, and included distended copies of the protein structures in the training set to better sample short-range interactions and obtain reasonable dynamic behavior.

A training set was generated in a similar manner to that used for ELSCA (a technical outline is given below), but because all atomic interactions are now being sampled, rather than just those between two molecules, many distinct molecules rather than interfaces were required. A set of 3000 protein chains resolved by X-ray diffraction, each chain containing <50% homology with any other, was created using the PISCES server (Wang and Dunbrack 2003). Because many of these protein chains were extracted from larger complexes, protein interfaces were sampled indirectly. Folding and binding of proteins are known to follow certain rules that themselves give rise to strong correlations that may cause overfitting. Therefore, 2500 random sequences were threaded onto backbone templates from the original PISCES-culled set. We took an additional precaution in response to observations that many CIRSE parameterizations produced unrealistic drops in the solvation energy during minimization or initial steps of a molecular dynamics run. In earlier tests with a different CIRSE formulation (data not shown), we observed these changes to be accompanied by bond stretching or contraction. Bond and angle flexions are the stiffest motions in biomolecular systems; the short-range interactions, which are the most difficult to parameterize for sheer paucity of data, therefore become overfit to interactions at equilibrium bond and angle values. The manifestation of such overfitting is unrealistic derivatives in the potential despite apparent success in reproducing the solvation energies of independent protein structures in their native states. After preparing the training set as described below, we also reprocessed our training set configurations to perturb the atoms by ±0.15 Å at random in all Cartesian directions. Pulling bonds 0.1–0.2 Å from equilibrium corresponds to stretching energies of 4–16 kcal/mol, well above the stretching effects we observed early versions of CIRSE to create. In all, the training set contained a total of 11,000 structures.

Apart from the procedure illustrated in the Supplemental Material, constraint equations were added to the matrix A to limit the values of certain parameters. In the LLSP framework, the constraints are harmonic with spring constant dimensions of inverse energy (kilocalories per mole-kilocalorie squared, in our case). The exact stiffness of each constraint depends on the overall size of A, and we did not try to optimize the stiffness of the constraints. We note that all individual parameters in the functions g and h are without physical meaning apart from their contribution to the model as a whole. These are therefore constrained to zero by a “loose” spring constant of 1.0/mol·kcal. The long-range dielectric constant for charge–charge interactions was set to 78.54, that expected for point charges in a solution of pure water at 300 K, by a “tight” spring constant of 107/mol·kcal. Constraining any parameter by such a tight spring constant effectively sets it to its target value. To keep the distance-dependent dielectric functions smooth, every n-th coefficient of f was coupled to the (n + 1)-th by the loose spring constant. Finally, a constraint of 10.0/mol·kcal was used to set the combined sum of all coefficients in f and f′ to −332.0636 kcal/mol, based on our observations that the solvation energy of a protein was roughly equal in magnitude and opposite to the gas-phase Coulombic energy of that protein, including interactions among all bonded atoms; this constraint was thus intended to place more of the burden of reproducing the solvation energy on the distance-dependent dielectric function, which is universal, and prevent overfitting in the pair potentials, for which less fitting data are available.

To fit what is still a very large number of parameters with a reasonable amount of training data, the energies of individual atoms were collected as well as the total energy of each molecular configuration. Each molecule was randomly divided into 10 mutually exclusive partitions. The row of matrix A corresponding to the entire configuration would be obtained by looping over all atom interactions in the configuration, computing the values of each basis function, and summing them in the appropriate column (see Supplemental Material). For each partition, the row of matrix A is obtained by summing the values of all basis functions for all interactions within the partition and all interactions between the partition and the rest of the molecule. The corresponding target energy in b is obtained by summing the energy of each atom in the partition, obtained from the benchmark model. Randomly partitioning the molecule has the advantage of breaking strong spatial and identity correlations between atom types that can give rise to compensatory errors in the model. However, the total energy is a necessary quantity for protein docking and design applications. We therefore allocated rows of A and entries of b for nine of the 10 partitions, and reserved the tenth place for the interactions and energy of the entire configuration.

Preparation of structures

Structures taken from the PDB were prepared as described previously (Cerutti et al. 2005). Briefly, structures were protonated using the GROMACS pdb2gmx module (Berendsen et al. 1995; Daura et al. 1996; van der Spoel et al. 1996; Lindahl et al. 2001) to determine the protonation state of histidine residues. Missing side chains were rebuilt using SCWRL3.0 (Cantescu et al. 2003), but missing residue backbones were replaced with terminal carboxyl and amino groups. In the case of a randomized sequence, all residues of the protein were rebuilt on the original backbone template with SCWRL3.0. All structures were then relaxed in vacuum using the AMBER8 sander module (Pearlman et al. 1995) and the AMBER ff99 potential (Cornell et al. 1995; Wang et al. 2000). Distended structures were created after the gas-phase minimization and therefore contained very high potential energy.

The solvation energy benchmark

It is typical in implicit solvent models to approximate the solvation energy as a sum of polar and apolar terms as in Equation 4:

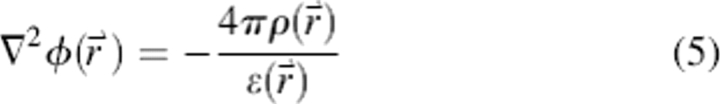

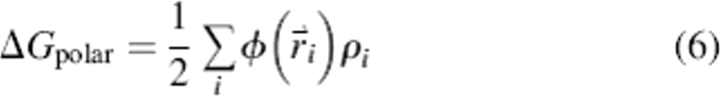

Similar to most GB approximations, a solution of Poisson's equation (McQuarrie 2000), shown in Equation 5 with ϕ being the electrostatic potential, ρ, the charge density, and ɛ, the dielectric constant, was used to approximate ΔGpolar in the CIRSE benchmark model:

|

ΔGpolar is obtained by computing the volume integral of charge times electrostatic potential for all solute atoms as in Equation 6:

|

In the polar part of the CIRSE benchmark, there was no implicit ion concentration, although in such a case the Poisson-Boltzmann equation could have been used. The charge distribution was taken from the AMBER ff94/99 charge set, while the solute volume was defined by a set of radii designed to reproduce charging energies of small molecules and proteins (Swanson et al. 2005) as calculated by free energy perturbation using the AMBER ff94/99 charge set and the TIP-3P water model (Jorgensen et al. 1983). An abrupt, molecular-surface boundary condition appropriate to these radii was used; this solute volume definition was critical to obtaining meaningful atomistic energy results. The charges of the solute were mapped to grids using cubic spline interpolation. The dielectric throughout the solute volume was set to vacuum permittivity, and the solvent dielectric was set to 78.54.

Poisson calculations were performed using the APBS software (Baker et al. 2001) compiled as a library in the same code, GRAPPLE, used to fit CIRSE. Calculations were carried out on several clusters of dual-processor Xeon machines with speeds of 2.8–3.6 GHz. More than 1 yr of CPU time was expended to compute Poisson calculations for the final training and test data.

After orienting each molecule to fit in a roughly cubic box, a coarse-grained solution of Poisson's equation was solved for a box 2.5 times larger than the molecule in all directions with boundary conditions set by the Coulombic electrostatic potential due to the solute's atomic partial charges in the dielectric of the solvent. Focusing calculations were done to reduce the grid spacing to 0.28 Å. Because of the extreme memory requirements of APBS (160 bytes/grid point), parallel solution of Poisson's equation was necessary for many structures. In this case, grids for different regions of the structure were set to overlap by at least 15% in all directions. Solutions were carried out with a minimum 800 MB of memory allocated per processor; this means that focused grids assigned to different processors overlapped by at least 6.8 Å in all directions. This level of resolution and grid overlap was found to be necessary for convergence in the atomistic energy values described in the next paragraph.

Electrostatic solvation energies for each atom and thus the entire structure were obtained from the energy computed by Poisson's equation by subtracting the energy of that atom computed by a corresponding, grid-based solution of the Coulombic electrostatic energy at vacuum permittivity.

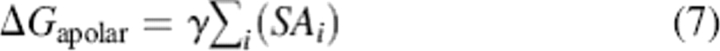

In GB simulations, an additional term is sometimes included for the apolar solvation energy (typically much smaller than the electrostatic solvation energy) such as the linear combination of pair overlaps model (LCPO) (Weiser et al. 1998). In the CIRSE benchmark, the apolar energy was computed as the solvent-accessible surface area SA of each atom i, defined by the same radii used in Poisson calculations, multiplied by a factor γ of 5 cal/mol·Å2 as in Equation 7:

|

Test cases

To test the usefulness of the CIRSE solvation model, we examined reproduction of its PBSA benchmark for test cases independent of the training set but comprising similar themes: native structure solvation energies, stringent optimization protocols, and protein design and docking applications.

NMR structures

A collection of native structures independent of our training set was provided by a set of 331 NMR models, each with at least eight conformations, identified by the PDB browser (Berman et al. 2000) as having <50% sequence similarity to one another. These structures were not subjected to residue repair by SCWRL3.0 or energy minimization in the gas phase. Although it is a valid question to what extent the structures produced by NMR are influenced by the refinement force field, none of these structures was solved using CIRSE, and all structures at the very least depict a large number of the protein's native contacts. An advantage of using NMR structures for validating CIRSE was that each model contains a range of native-like conformations, permitting evaluations of ΔGsolv, the absolute solvation energy, as well as ΔΔGsolv, the difference in solvation energy between two structures, with respect to the P/SA benchmark model.

Energy minimization

To test the behavior of CIRSE in the context of molecular mechanics energy minimization, three structures (the barnase-barstar complex 1BRS, the methionine sulfoxide reductase protein 1NWA, and the fasciculin inhibitor extracted from 1FSS) were energy-minimized by 200 steps of conjugate gradient minimization in vacuum, without constraints, using the AMBER ff99 potential with improvements suggested by Carlos Simmerling et al. (Simmerling et al. 2002) (hereafter AMBERgp) to generate configurations that were free of steric clashes but contained nonoptimal solvent effects. The structures were then energy-minimized by the conjugate gradient method to a tolerance of 0.001 kcal/mol-step using AMBERgp plus the CIRSE potential. After each step of minimization with CIRSE, the configuration was saved and re-evaluated in terms of the P/SA solvation energy benchmark model for comparison to the CIRSE-estimated energy. To further test the performance of CIRSE during energy minimization, all structures from the training set with PDB IDs 1A??, 1B??, and 1C?? (where ? represents any alphanumeric character), a total of 273 proteins, were energy-minimized as described above. P/SA calculations were performed on the final states of these structures so that CIRSE estimates of the initial states (energy-minimized in the gas-phase) and final states could be compared.

Rotamer optimization

As an additional test, we applied a large rotamer library to optimize side-chain conformations on the native protein backbones of the first structure from six NMR ensembles: 1ADZ, 1CCV, 1DRS, 1EWS, 1GJQ, and 1H2P. These six structures were chosen for their small size (30–70 residues) and globular, folded shape. Rotamers for each residue were taken from the Dunbrack and Karplus backbone-independent rotamer library (Dunbrack and Karplus 1993) (roughly 420 rotamers in all 20 amino acids). To increase diversity of this library, in accordance with a previous study (Leach and Lemon 1998), we allowed the hydroxyl protons on serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues to take dihedral angles of 0° or 180° with their 1:4 carbon neighbors. The Dunbrack and Karplus rotamer library, with additional hydroxyl proton rotamers, was termed the “canonical library” and its rotamers the “canonical rotamers.” “Perturbed” rotamers were included to improve sampling, based on the canonical rotamers but with dihedral angles randomly perturbed up to 30° and bond angles near the base of the side chain perturbed up to 7.5°.

To make a rotamer optimization procedure that was more strenuous than those used in routine protein docking or design calculations yet still computationally tractable, the procedure itself became somewhat detailed. Essentially, moves were made in which rotamers were generated randomly and optimized by a Dead-End Elimination scheme, which was supplemented by a simulated annealing scheme to ensure convergence before the end of each move. Moves were accepted if and only if they lowered the energy of the final configuration. Initially, native side chains were removed, excepting those for proline and cysteine in disulfide bridges, which were considered rigid. The canonical rotamers for each residue in the sequence, as well as two perturbed rotamers per canonical rotamer, were then grafted onto the native backbone. Whenever applying rotamers to the backbone, those rotamers exhibiting steric clashes with the backbone in excess of 1000 kcal/mol were culled immediately; likewise, if two rotamer choices caused side chains to clash with each other by 1000 kcal/mol, this pair was not considered simultaneously in the combinatorial search. No mutations were admitted in the choice of these rotamers (i.e., only rotamers for arginine were grafted onto the backbone at the site of an arginine). The HERO Dead-End Elimination (DEE) computational protein design technique (Gordon et al. 2002) was used to optimize the conformation of this set of side chains in the “global refinement” procedure. In the event that HERO did not converge, a simulated annealing (SimAn) scheme was used to find the optimal combination out of the remaining rotamers. Because rotamers with severe clashes were culled as described above, all rotamers at one or more residues were eliminated from the configuration space. If this occurred during global refinement, the side-chain refinement was declared a failure, and no further attempts to refine the configuration were made. The conformation resulting from successful global optimizations was retained, and new rotamers from the canonical library, barring duplicates and again permitting no mutations, were grafted onto the backbone. One residue in the protein was selected at random. In this residue and all residues whose Cα atoms lay within 8 Å of the selected residue's Cα atom, seven perturbed rotamers were created corresponding to each of the rotamers thus far used to represent each residue (i.e., canonical rotamers and any retained from previous refinements). Effectively, this used a 3600-rotamer library to repack side chains in a 16-Å-diameter patch of the protein, and a 450-rotamer library to repack all other side chains. DEE/SimAn was used to reoptimize the side-chain configuration, and the optimal configuration was retained. The “patch refinements” just described were performed 50 times on each of the six structures. Because DEE can sometimes leave high potential energy barriers in the energy landscape for the remaining rotamers, the SimAn procedure can become trapped in local minima. To circumvent this problem, DEE/SimAn moves were only accepted if they resulted in a lower final energy. The entire scheme is thus referred to as Low(DEE/SimAn).

Following the rotamer optimization procedure, conjugate gradient minimization was performed to a tolerance of 0.001 kcal/mol-step. Rotamer and dynamic minimization were carried out under the AMBERgp + CIRSE potential, as before. P/SA calculations were performed on the structures resulting from global refinement, all patch refinements, and energy minimization.

Although our rotamer library was very large and DEE is very effective at finding the global minimum in discrete-space searches, the continuous conformational space of a protein's side chains is still so vast that no current search technique could find the absolute global minimum. The purpose of the Low(DEE/SimAn) technique was merely to perform more strenuous rotamer optimization than most investigations would ever use, and hopefully to arrive at a level of energy that further rotamer optimization could not reduce.

Protein design

To further test the performance of CIRSE during protein design applications, 1000 random sequences were grafted onto the protein backbones from each of the six proteins above. After energy minimization to relieve clashes, the AMBERgp + CIRSE potential was used to perform the global refinement and patch refinement scheme described above for each of the structures. The final structure produced by rotamer-based refinement (without energy minimization) was scored by the P/SA benchmark for comparison to the CIRSE-estimated solvation energy.

Protein docking

Test cases for protein docking were generated by docking nine pairs of interacting proteins from the Chen protein docking benchmark (Chen et al. 2003) (derived from PDB IDs 1A0O, 1AVZ, 1BRC, 1CGI, 1PPE, 1STF, 1TAB, 1TGS, and 2SNI). The proteins were chosen based on their relatively small size and absence of cofactors near their interfaces. Bound coordinates of each complex were used. The DOT software (Mandell et al. 2001) was used to determine a set of 1000 docked configurations for each protein pair with high shape complementarity and roughly favorable electrostatic interactions. This set of DOT suggestions was then refined using an optimization cycle consisting of rotamer optimization followed by intermittent side-chain energy minimization in the context of fixed protein backbones and rigid-body moves in which the two proteins moved relative to one another. In each cycle, rotamers from the native protein configuration and the canonical library (without additional variants) were optimized by DEE/SimAn, and energy minimizations—first of the side-chain atoms and then of the orientation of the two proteins as rigid bodies—were carried out to a 0.5 kcal/mol-step tolerance. The rotamer optimization/energy minimization cycle was repeated to a convergence of 2.0 kcal/mol-cycle. Each docked solution was finally energy-minimized without constraints (e.g., the backbone was considered flexible) to a convergence of 0.001 kcal/mol-step. The refined solutions for each DOT suggestion were rescored using the P/SA benchmark for comparison to the CIRSE estimates of the final energy.

Electronic supplemental material

Parameters obtained for the CIRSE potential used in this work, examples of the functional form of the CIRSE potential between different atom types, and some notes on implementation are included.

Acknowledgments

D.S.C. thanks Jessica M.J. Swanson for helpful conversations on selecting the PB benchmark, and Robert Konecny, T. Drew Schaffner, and Christopher Misleh for assistance with computational resources. This research was supported in part by grants from the NSF, the NIH, the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, the National Biomedical Computation Resource, the San Diego Supercomputer Center, Accelrys, Inc., and the UCSD Achievement Rewards for Collegiate Scholars Program.

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: David S. Cerutti, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0365, USA; e-mail: dcerutti@mccammon.ucsd.edu; fax: (858) 534-4974.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051985106.

References

- Baker N.A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M.J., McCammon J.A. 2001. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Applications to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 10037–10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beglov D. and Roux B. 1996. Solvation of complex molecules in a polar liquid: An integral equation theory. J. Chem. Phys. 104: 8678–8689. [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.J.C., van der Spoel D., van Drunen R. 1995. GROMACS: A message-passing molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91: 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. 2000. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born M. 1920. Volumen und hydratation swärme der lonen. Z. Phys. A 1: 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cantescu A.A., Shelenkov A.A., Dunbrack R.L. Jr. 2003. A graph theory algorithm for protein side-chain prediction. Protein Sci. 12: 2001–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti D.S., Ten Eyck L.F., McCammon J.A. 2005. Rapid estimation of solvation energy for simulations of protein–protein association. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 1: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Mintsenis J., Janin J., Weng Z. 2003. A protein–protein docking benchmark. Proteins 52: 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]